Submitted by International Review on

Since the end of 1973 western governments and economists have pointed to the rise in oil prices as their main explanation for the economic crisis and its consequences: unemployment and inflation. When companies close down, the workers thrown into the street are told: ‘oil is to blame’; when workers see their real wages shrink under the pressure of inflation, the mass media tells them ‘it’s because of the oil crisis’. The bourgeoisie is using the oil crisis as a pretext, an alibi, to make the exploited swallow the economic crisis. In the propaganda of the ruling class, the oil crisis is presented as a sort of natural disaster men can do nothing about, except passively submit to those calamities called unemployment and inflation.

But ‘nature’ has nothing to do with the fact that oil merchants are now selling their goods at a higher price to other merchants. The oil increase is not nature’s doing but the consequence of capitalist trade relations.

Like all exploiting classes in history, the capitalist class attributes its privileges to the will of nature. The economic laws which make them the masters of society are, in their mind, as natural and unchangeable as the law of gravity. But with time these laws have become outmoded in terms of the productive forces; when their continuation can only cause crises which plunge society into misery and desolation, the privileged class always sees this as ‘nature’s’ fault: nature is not generous enough or there are too many human beings on earth, etc. Never in their wildest imagination would they want to conceive that the existing economic system is at fault, is anachronistic and obsolete.

At the end of the Middle Ages, in the decadence of the feudal system, monks announced the end of the world because the existing fertile lands had been exhausted. Today we are told ten times a day that if everything is going wrong, it is because existing oil sources have been exhausted.

Has nature really run out of oil?

In March 1979, the oil producing countries of OPEC met together to solemnly proclaim that they were going to reduce oil production once again. They are lowering production in order to maintain price levels, just as peasants may destroy their surplus fruit to avoid a collapse in prices.

Europe risks facing an oil scarcity in 1980 they tell us. Perhaps, but who still believes that it is because of a natural, physical scarcity?

The OPEC countries do not produce at capacity, far from it. For several years now new oil fields have been put to use in Alaska, the North Sea, and Mexico. Almost every week new oil deposits are discovered somewhere in the world. Furthermore it is said that oil deposits trapped in shale, in a form more costly to extract, are enormous in comparison to known oil deposits today. How then can we talk about a physical scarcity of oil?

It is perfectly logical to think that one day a certain ore or other raw material will be exhausted because of man’s unlimited use of it. But this has nothing to do with the fact that oil merchants decide to reduce capacity so as to maintain profits. In the first case it really is a question of the end of nature’s bounty; in the second it is simply the case of a vulgar speculative operation on the market.

If the world economic situation was otherwise ‘healthy’, if the only problem was simply the physical and unexpected exhaustion of oil in nature, then we would not be seeing a slowdown in the growth of trade and investment as we do today but a huge economic boom instead: the world’s adaptation to new forms of energy would set off a veritable industrial revolution. Certainly there would be restructuration crises here and there with factories closing down and lay-offs in some sectors, but these closures and lay-offs would find an immediate compensation in the creation of new jobs.

Today we are witnessing something completely different: countries producing oil the most profitably are reducing production; the factories which close are not replaced by new ones; investment in new forms of energy remains negligible in most major countries.

The idea of a physical lack of oil in nature is used by economists and the mass media to explain the dizzying rise of oil prices in 1974 and in 1979. But how can the spectacular rise in the world market prices of all basic materials in 1974 or in 1977 be explained? How can the feverish rise in basic metals like copper, lead, and tin since the beginning of the year be explained? If we follow the ‘experts’ of the bourgeoisie, we would have to believe that oil is not the only thing that is giving out in nature, but also most metals and even food products. Between 1972 and 1974 the price index of metals and ore exported in the world (aside from oil) has more than doubled; food prices have almost tripled. In the second quarter of 1977 these food products cost three times more on the world market than in 1972. We would have to believe that nature is drying up all of a sudden not just in oil but in almost everything else; this is just absurd.

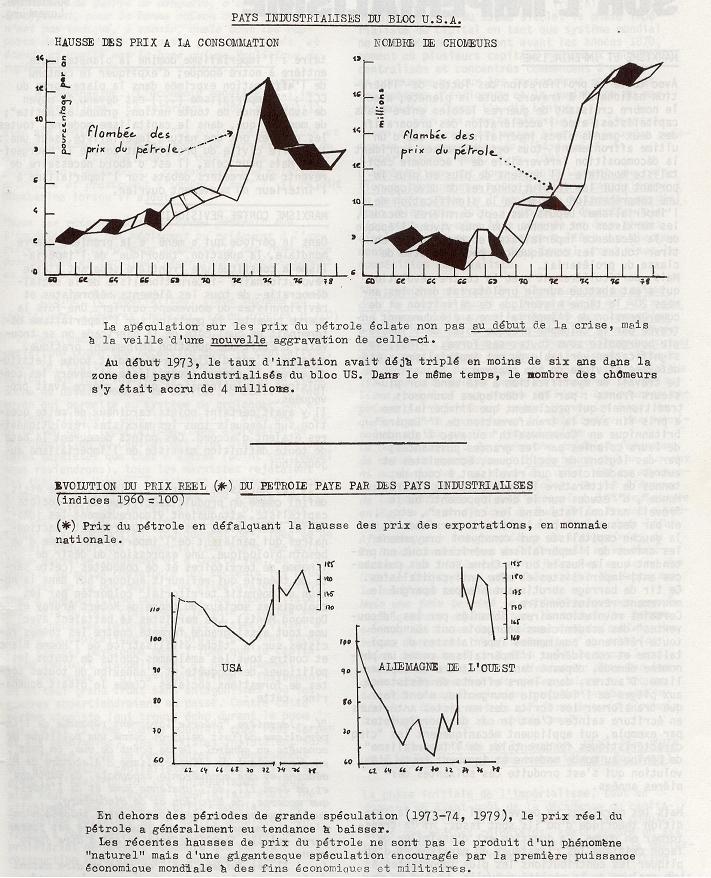

The theory of the physical exhaustion of nature hardly manages to explain the rise in oil prices, but it has even greater difficulty explaining why the real price of oil, as paid by the importing, industrialized countries, (that is the price paid taking into account the growth of world inflation and the evolution of the value of the dollar1 decreased regularly before 1973-74 and afterwards, until 1978. Between 1960 and 1972 the real price of imported crude oil decreased 11% for Japan, 14% for France and 20% for Germany! In 1978 this same price decreased in relation to 1974 or 1975 levels by 14% for Japan, 6% for France and 11% for Germany.

How could the price of a raw material that is supposedly being physically exhausted be diminishing to the point of obliging its producers to artificially reduce their production so as to avoid a collapse of prices?

If we want to understand the present ups and downs in the prices of raw materials we cannot look to the greater or lesser generosity of Mother Nature, but to the decomposition of capitalist trade. We are faced with not the sudden discovery of a grotesque natural scarcity but a huge speculative operation on the raw materials market. This is not a new phenomenon: all major capitalist crises are accompanied by speculative fever in the raw materials market.

Speculation: a typical characteristic of capitalist economic crises

The real source of all capitalist profits resides in the exploitation of workers in the course of the production process. Profit, surplus value, is the surplus labor extracted from wage earners. When everything goes well, that is when what is produced gets sold at a sufficient rate of profit, capitalists reinvest these profits in the production process. The accumulation of capital is this process of transforming the surplus labor of the workers into capital: new machines, new raw materials, new wages, to exploit new quantities of living labor. That is the way capitalists ‘make money work’ as they call it.

But when things are going badly, when production does not give enough of a return because markets are lacking, this mass of capital in money form that is seeking investments, takes refuge in speculative operations. It is not that capitalists prefer this sort of operation where risks are so great that you face ruin from one day to the next; on the contrary they would prefer the ‘peaceful’ road of exploitation through production. But when there is less and less profitable investment available in production, what can you do? Keeping your money in the vault means seeing its value diminish everyday due to monetary erosion. Speculation is a risky placement but it can bring fast and big returns. That is why every capitalist crisis is witness to an extraordinary degree of speculation. The law supposedly prohibits speculation but those who speculate are the very ones who make the laws.

Very often this speculation polarizes around raw materials. In the economic crisis of 1836, Beagle, the director of the US Bank, taking advantage of the fact that the demand for cotton in Great Britain was still strong, bought up the whole cotton crop to sell it at exorbitant prices to the British later. Unhappily for him, the demand for cotton collapsed in 1839 under the pressure of the crisis, and the cotton stocks carefully gathered in the heat of the speculative burst were worthless. Cotton prices collapsed on the world market, adding to the already large number of bankruptcies (1000 banks went bust in the US).

After provoking a speculative price rise in raw materials, the crisis has the effect of collapsing prices because of a lack of demand. These sudden bursts of rising raw material prices followed by a dizzying fall are typical of speculation in a time of crisis. This phenomenon was particularly clear in the crises of 1825, 1836 and 1867 in cotton and wool; in the crises of 1847 and 1857 in wheat; in 1873, 1900 and 1912 in steel and cast-iron; in 1907 in copper; and in 1929 on almost all metals.

Speculation is not the work of isolated, shady individuals operating illegally, or of greedy little stockpilers, as the press likes to paint them. The speculators are governments, nation states, banks large and small, major industries, in short, those who hold most of the monetary mass seeking profits.

In times of crisis speculation is not just a 'temptation' capitalists are capable of avoiding. A banker who has the responsibility of paying interest to thousands of savings accounts has no choice. When profits are getting rare, you have to take them where you can get them. The hypocritical scruples of times of prosperity, when laws are made 'prohibiting speculation', disappear and the most respectable financial institutions throw themselves headlong into the speculative whirlpool. In the capitalist world the one who makes the profits survives. The others are eaten up. When speculation becomes the only way to make profits, the law becomes: he who does not speculate or speculates badly is destroyed.

What is being called the oil crisis is in fact a huge world speculative operation.

Why oil?

Oil has not been the only object of speculation in recent years. Since the devaluation of the pound sterling in 1967, speculation has been increasing in the entire world, attacking an overgrowing list of products: currencies, construction, raw materials (vegetable or mineral), gold, etc. But oil speculation is particularly important because of its financial repercussions. It has set off movements of capital of such size and rapidity as to be largely unprecedented in history. In a few months, a gigantic flow of dollars went from Europe and Japan towards the oil-producing countries. Why did speculation on oil bring such large profits?

First of all because modern industry relies on electricity and electricity relies essentially on oil. No country can produce without oil. Speculation based on the blackmail of an oil shortage is blackmail with economic clout.

But oil is not only indispensable for production and construction. It is also indispensable for destruction and war. Most of the modern arsenal of weapons, from tanks to bombers, from aircraft carriers to trucks and jeeps, works on oil. To arm yourself is not only to produce weapons but to control the means of making these weapons work as long as you need them. The armaments race is also the oil race.

Oil speculation therefore touches a product of primary economic and military importance. That is one of the reasons for its success -- at least for the moment. But it is not the only reason.

The blessing of American capital

One of the favorite themes of the new commentators’ gibberish is the oil crisis as ‘the revenge of the under-developed countries against the rich ones’. By a simple decision to reduce their production and raise the price of oil, these countries, who are part of the victims of the third world, previously condemned to produce and sell raw materials cheaply to the industrialized countries, have got the great powers by the throat. A real David and Goliath story for our times!

Reality is quite another thing. Behind the oil crisis is US capital. Just consider two important and obvious facts:

1. The major powers of OPEC are very strongly under the domination of US imperialism. The governments of Saudi Arabia, the major oil exporter in the world, of Iran in the time of the Shah, or Venezuela, to take only a few examples, do not make any crucial decisions without the agreement of their powerful ‘protector’.

2. Almost all world trade in oil is under the control of the large American oil companies. The profits made by these companies, because of the variations in oil prices, are so enormous that the US government recently had to organize a parody of government hearings on the television to divert the anger of a population which is feeling the effects of austerity programs justified by the ‘oil crisis’ onto the ‘Seven Sisters’ -- the major oil companies.

If this is not enough to prove the decisive role played by the US in the oil price rises, consider some of the advantages the strongest economic power drew from the ‘oil crisis’:

1. On the international market, oil is paid in US dollars. Concretely this means that the US can buy oil simply by printing more paper money, while other countries have to buy dollars.2

2. The US imports only 50% of the oil it needs. Their direct competitors on the world market -- Europe and Japan -- have to import almost all their oil; any price rise in oil therefore has a much greater effect on production costs of European and Japanese goods. The competitiveness of US goods is thus automatically increased. It is not an accident that US exports have increased enormously after each oil price rise to the detriment of their competitors.

3. But it is surely on the military level that the US has benefited the most from the oil crisis.

As we have seen, oil remains a major instrument of war. The oil price rise allowed for the profitable exploitation of new oil fields in or near the US (Mexico, Alaska and other US deposits). In this way US military potential is less dependent on oil deposits in the Middle East which are far from Washington, and close to Moscow. In addition, the huge oil revenues have financed the ‘Pax Americana’ in the Middle East through the intermediary of Saudi Arabia. In fact Egypt’s costly passage into the US bloc was partly paid for through aid from Saudi Arabia in the name of Arab brotherhood. Saudi Arabia directly influenced the policy of countries like Egypt, Iraq, Syria (during the Lebanon conflict) through their economic ‘aid’ financed out of oil revenues. Saudi Arabian financial aid to the PLO is not entirely foreign to the budding rapprochement between the PLO and the US bloc.

American imperialism has thus given itself the luxury of having its competitors and allies, Europe and Japan, finance its international policy. Thus for economic and military reasons the US has an interest in letting oil prices rise and even encouraging this.

The attitude of the Carter government during the burst of speculation brought on by the interruption of deliveries from Iran is very indicative. While Germany and France were trying to choke off the speculation developing on the ‘free market’ in Rotterdam in the first half of 1979, the US government cynically announced it was prepared to buy any amount of oil at a higher price than any reached at the Dutch port. Despite special envoys from Bonn and Paris, sent to Washington to protest against this ‘knife in the back’, the White House would not go back on its offer.

Whatever the different reasons for the price rise, one issue remains: what are the effects on the world economy? Is the official propaganda right in saying that the oil crisis is responsible for the economic crisis?

The effects of the oil price rise

There is no doubt that the rise in the price of raw materials is a handicap for the profitability of any capitalist enterprise. For industrial capital raw materials constitute an overhead expense. If expenses increase, the profit margin proportionally decreases. Industrial capital has only two ways of fighting against this decline in profits:

-- reducing overhead costs in other ways especially by reducing the price of labor;

-- compensating for overhead costs by increasing the sale price.

Capitalists usually use the two methods at the same time. They try to reduce their overheads by imposing austerity policies on the workers; they try to maintain profits by increasing prices and thus fuelling inflation. Thus it is certain that the oil price rise is a factor forcing each national capital to make new efforts towards maximizing profits: eliminating the least productive sectors, reducing wages, concentrating capital further. It is thus true that oil prices are partly responsible for increased inflation.

The oil increase is indeed an exacerbating factor in the crisis. But contrary to what the propaganda of the media disseminates, it was only that -- an exacerbating factor and not the cause or even the major cause of the economic crisis.

The economic crisis did not begin with the oil increases. Oil speculation is merely one of the consequences of the economic disorders which have plagued capitalism since the end of the 1960s. To hear bourgeois ‘experts’ speak, one would think that before the fatal date of the second half of 1973 everything was rosy in the world economy. To justify their austerity policies, these gentlemen forget or pretend to forget that at the beginning of 1973, before the big oil price increases, the inflation rate had doubled in the US and tripled in Japan in less than a year. They pretend to forget that between 1967 and 1973 capitalism went through two serious recessions: one in 1967 (the annual growth rate of production fell by half in the US -- 1.8% in the first half of 1967 -- and fell to zero in Germany), and the other in 1970-71 when production declined absolutely in the US. They forget or hide the fact that the number of unemployed in the OECD countries (the twenty-four industrialized countries of the US bloc) had doubled in six years, from 6 million and a half in 1966 to more than 10 million in 1972. They ignore the fact that at the beginning of 1973, after six years of monetary instability that began with the devaluation of the pound in 1967, the international monetary system definitively collapsed with the second devaluation of the dollar in two years.

The speculation in oil did not burst in upon a serene and prosperous capitalist economy. On the contrary, it appeared as yet another convulsion of capitalism shaken for the past six years by the deepest crisis since World War II.

It is absurd to explain the difficulties of the 1967 to 1973 period by the oil price rises which followed it in 1974; it is just as absurd to consider the oil price increase as the cause of the economic crisis of capitalism.

*******************

Oil speculation dealt a blow to the world economy but it was neither the first nor the most serious one. The purely relative importance of the blow can be measured ‘negatively’ so to speak by considering the situation in an industrialized country which has managed to eliminate the oil problem by exploiting its own deposits. Such is the case of Great Britain which is less dependent on oil imports because of its fields in the North Sea. In 1979 the rate of unemployment was twice that of Germany and three times the rate in Japan -- two countries which nevertheless have to import almost all their oil. Inflation of consumer prices in Great Britain is double Germany’s and nine times greater than Japan’s. And finally, the growth rate of production is the weakest of the seven major western powers (in the first half of 1979 gross production had not increased but decreased by 1% in annual terms) .

The causes of the present crisis of capitalism are much more profound than the consequences of oil speculation. Since the beginning of the 1960s capitalism has been in a headlong race to escape the consequences of the end of the period of reconstruction. For more than ten years the industrial regions destroyed in World War II have not only been reconstructed -- thereby eliminating one of the major markets for US exports -- but have become powerful competitors of the US on the world market. The US has become a country which exports less than it imports and therefore must cover the world with its paper money to finance its deficit. For ten years, since the end of the reconstruction process, world growth has been resting essentially on credit sales to underdeveloped countries and on the US’ ability to finance its deficit. However, both the former and the latter are on the brink of financial bankruptcy.

The debt of the third world countries has reached unbearable proportions (the equivalent of the annual revenue of a thousand million men in these regions). The US is heading into a recession as a way to reduce their imports and stop the growth of their debts. The recession beginning in the US is inevitably the sign of a world recession, a recession which according to the observable progression from 1967 onwards will be deeper than the three previous ones.

Speculation on the price of oil is only a secondary aspect of a much more important reality: the fact that capitalist production relations are definitively out of step with the possibilities and needs of humanity.

After almost four centuries of world domination, capitalist laws have exhausted their validity. From being a progressive force, they have become an obstacle to the very survival of humanity.

It is not the ‘Arabs’ who have brought capitalist production to its knees. Capitalism is economically collapsing because it is increasingly undermined by its internal contradictions, and mainly by its inability to find enough markets to sell its production profitably. We are living at the end of a round in the cycle of crisis-war-reconstruction which capitalism has imposed on humanity for more than sixty years.

For humanity the solution is not to be found in lowering the price of oil nor in lowering wages but in eliminating wage slavery, in eliminating the capitalist system east and west.

Only with a new form of organization for world society, following real communist principles, will we escape the endless barbarism of capitalism in crisis.

R. Victor

1 The fact that the price of oil increasing is not significant in itself because world inflation affects all products and revenues. For an oil-importing country the real question is whether or not the price of oil is increasing slower or faster than the price of other exports. For an oil-importing country the rise in oil prices has a negative effect only to the extent that it rises faster than that of prices of other commodities which it exports, that is to say, the source of its own revenues on the world market. What difference does it make to pay 20% more for oil if one’s own export prices can be raised by the same amount at the same time?

2 The danger of new pressures towards devaluation of the dollar because of the new volume of paper money put into circulation by the US is relatively limited by the increase in the demand for dollars provoked by the rise in oil prices.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us Digg

Digg Newskicks

Newskicks Ping This!

Ping This! Favorite on Technorati

Favorite on Technorati Blinklist

Blinklist Furl

Furl Mister Wong

Mister Wong Mixx

Mixx Newsvine

Newsvine StumbleUpon

StumbleUpon Viadeo

Viadeo Icerocket

Icerocket Yahoo

Yahoo identi.ca

identi.ca Google+

Google+ Reddit

Reddit SlashDot

SlashDot Twitter

Twitter Box

Box Diigo

Diigo Facebook

Facebook Google

Google LinkedIn

LinkedIn MySpace

MySpace