Submitted by ICConline on

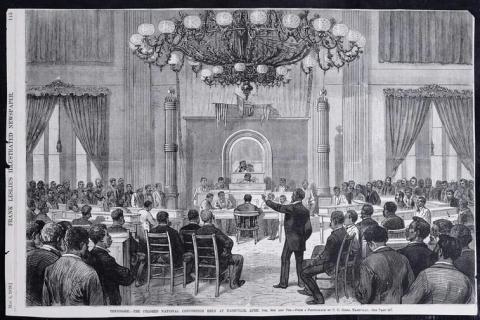

Colored National Labor Union Convention, 1869

The campaign around “Black Lives Matter” (BLM) has led many people to look for references in the history of the struggle against the oppression of and violence against black people. Among the most well-known black activist are Marcus Garvey, Malcom X, and Martin Luther King. But communists do not base their political orientation on activists fighting for equal rights within capitalism. For communists the goal of the struggle lies beyond the limits of the present mode of production. The real abolition of all forms of racial oppression can only be achieved through the fight of the international working class for communism. The crucial question is: what does that mean concretely, except for the fact that communists reject the anti-racist campaigns, which look for answers in the framework of bourgeois politics?

In order to be able to respond to this question we have to base ourselves on the theoretical achievements of marxism. Therefore we must examine how the political vanguard pf the workers’ movement conducted the theoretical-political combat with regard to the “Negro question” in the history the U.S. Why the U.S.? Because in the U.S. from the first days the workers’ movement faced the biggest obstacles to the unification of its struggle because of the racial ideology which had systematically presented black people as inferior to white people.

Against this background the workers’ movement in the U.S., throughout its history, has been challenged with working out a clear position on this question, and with taking the necessary steps to integrating black workers into the struggle of the whole working class. The first step was made in the second half of the 19th century, beginning with the “American Workers League” (AWL); the second step was made after 1901 by the “Socialist Party of America” (SPA); and the third was made by the different communist organisations after the founding of the Third International, to begin with the “Communist Party of the USA” (CPUSA).

On the basis of a critical examination of these theoretical-political positions, acquired in the course of the history of the marxist movement in the U.S., this short series intends to make a thorough critique of the positions of more recent political expressions of the workers’ movement, in particular those of the Trotskyist Left Opposition of the 1930s.

The marxist position on slavery in the U.S.

In the Communist Manifesto Marx and Engels emphasized that as long as oppression exists anywhere in the world, nobody will be free: “Now-a-days, a stage has been reached where the exploited and oppressed class (the proletariat) cannot attain its emancipation from the sway of the exploiting and ruling class (the bourgeoisie) without, at the same time, and once and for all, emancipating society at large from all exploitation, oppression, class distinction and class struggles." (Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, The Communist Manifesto)

The first proletarian organisation in the U.S.A. to recognise that the abolition of slavery was a precondition for the emancipation of wage labour was the “American Workers’ League” (AWL), founded in 1852. One of its most prominent members was Joseph Weydemeyer. At a meeting of the AWL, on 1 March 1854, his proposed resolution was passed with the following sentence: “Whereas, this [Nebraska] bill authorizes the further extension of slavery, we have protested, do now protest and shall continue to protest most emphatically against both white and black slavery” (Karl Obermann, Joseph Weydemeye, Pioneer of American Socialism; https://www.redstarpublishers.org/Weydemeyer.pdf)

In 1863, one year before the founding of the International Workingmen’s Association (IWA), workers in Great Britain expressed their support for the abolition of the slavery, as they rallied in London and Lancashire and drafted letters and other declarations of support for the Union side in the American Civil War. Under the slogan “all for one, and one for all” they remained steadfast in their support for the struggle against the any government “founded on human slavery”. The meeting in London, which was attended by 3000 workers, passed a resolution declaring that “the cause of labour and liberty is one all over the world”.

Nearly twenty years after the publication of the Communist Manifesto Marx repeated, in different words, his position on the impossibility of freedom for all if some are still oppressed. In his letter to François Lafargue he wrote that with regard to the “Negro question” “Labour cannot emancipate itself in the white skin where in the black it is branded”. (12 November 1866) This idea became the inspiration for one of the most famous ideas of the International Workingmen’s Association (IWA) in the expression of its solidarity with the oppressed in the world, in particular with the black slaves in the New World: as long as the labour of the Negroes is so shamefully exploited, that of the whites will never be emancipated either.

Marx and Engels stressed the “revolutionising” influence of the American Civil War on the development of the workers’ movement in the US. Even if they did not characterize it as a revolutionary war, they believed that it really advanced the cause of the working class, and opened the perspective for a united struggle of the workers, black and white alike. “In the States themselves, an independent working class movement, looked upon with an evil eye by your old parties and their professional politicians, has since that date sprung into life”. (“IWMA: Address to the nation labor union of the United States”; May 12, 1869; https://www.marxists.org/history/international/iwma/documents/1869/us-labor.htm)

Chattel slavery in the “New World”

Slavery existed already in the U.S. before the first ship with black slaves arrived in 1619. Under British colonial rule “so-called ‘persistent rogues’ were banished to ‘parts beyond the seas’, which meant that tens of thousands of men, women and children (…) were simply rounded up and shipped off to work in the tobacco fields of Virginia, where many were worked to death or tortured if they tried to escape. The largest single group were convicts; (…) who could be granted royal mercy in exchange for transportation to the colonies.” (“Notes on the early class struggle in America - Part I”; https://en.internationalism.org/worldrevolution/201303/6529/notes-early-...)

Just like the white slaves, the first black people to arrive in U.S. were indentured slaves - persons bound to an employer for a limited number of years. But in less than one hundred years after the arrival of the first 20 blacks, the British colonial rule inaugurated a barbaric system of chattel slavery. Chattel slaves were not thought of as people, but as objects, as property, like livestock. This system was much worse than the slave systems that normally existed in previous centuries. The final stage of the establishment of chattel slavery in all the British colonies was concluded in 1750.

Under the specific conditions of chattel slavery “The methods the bourgeoisie used to control its growing black slave army [were] refined into a system of much greater and more sophisticated barbarity, specifically designed to ensure the slaves’ psychological destruction, demeaning, degrading and humiliating them in every way to prevent them from identifying with their own interests against their exploiters. (“Notes on the early class struggle in America - Part I”; https://en.internationalism.org/worldrevolution/201303/6529/notes-early-...)

While chattel slavery was generalised in the course of the seventeenth century, Marx linked the introduction of chattel slavery to the development of the cotton industry on a massive scale. “Whilst the cotton industry introduced child slavery in England, it gave in the United States a stimulus to the transformation of the earlier, more or less patriarchal slavery, into a system of commercial exploitation. In fact, the veiled slavery of the wage workers in Europe needed, for its pedestal, slavery pure and simple in the new world.” (Karl Marx, Capital Volume I, Chapter XXXI: “Genesis of the Industrial Capitalist”)

Chattel slavery was mainly introduced where the labour done was relatively simple, but extremely labour-intensive, requiring field hands to spend long hours bending over plants under the blazing hot sun. It was most common on plantations based on the large-scale growing of a single crop, like sugar and cotton, in which output was based on economies of scale. Systems of labour, such as the gang system (continuous work at the same pace throughout the day), were to become prominent on large plantations where field hands were monitored and worked with factory-like precision.

But the economics of slavery could only exist for centuries by means of a whole culture of control with political, social, and ideological formulations to hold dominance over the enslaved blacks and to keep the indentured whites in line. To accomplish the subjugation of the slaves to the system of chattel slavery the slave-owner used “the discipline of hard labor, the breakup of the slave family, the lulling effects of religion (…), the creation of disunity among slaves by separating them into field slaves and more privileged house slaves, and finally the power of law and the immediate power of the overseer to invoke whipping, burning, mutilation, and death.” (Howard Zinn, A People’s History of the United States; Chapter 2: “Drawing the Color Line”; https://www.historyisaweapon.com/defcon1/zinncolorline.html)

The ideological justification of black chattel slavery

Given the fact that the black Africans were subjugated by the white Europeans, the most obvious culture of control was along colour-oriented lines. “Slavery could survive”, wrote Winthrop Jordan, “only if the Negro were a man set apart; he simply had to be different if slavery were to exist at all”. (Cited by: Harold M. Baron; “The Demand for Black Labor: Historical Notes on the Political Economy of Racism”; https://repository.library.brown.edu/studio/item/bdr:89216/pdf/) “New World” slavery thus wedded skin colour to class in ways never seen before.

Slavery in the ancient and the early medieval world was not based on racial but on religious distinctions.

The shift from religion to colour as justification emerged in European thinking after 1450, beginning with the Spanish and Portuguese. As late as the 17th century, slavery in North America still did not automatically mean black slavery since there were also 100.000s indentured white slaves deported to the U.S. It was only in 1680s and 1690s that the British began to specify that Africans were doomed to a slave existence because of their colour. For this cause they no longer emphasised their religion and begin to call themselves white, emphasising division by colour.

To justify the forcible enslavement of Africans in the “New World”, racism - the ideology that marked people as inferior by observable differences such as skin colour - was fashioned. “Pre-existing derogatory imagery of darkness, barbarism, and heathenism”, wrote Winthrop Jordan, “was adapted to formulate the psychology and doctrines of modern racism.” (Cited by: Harold M. Baron, “The Demand for Black Labor, Historical Notes on the Political Economy of Racism”; https://repository.library.brown.edu/studio/item/bdr:89216/pdf/) And with one purpose only: the debasement and the dehumanisation of black people. Black people had to be seen as inferior to white people and so deserved to be slaves. The colour of their skin became a brand that kept them, and all of their children, enslaved for generations.

At the end of the 18th century, when voices for the abolition of slavery began to be raised, pseudo-scientific racism was even called upon to justify chattel slavery of black people. One of these voices was Thomas Jefferson, slave owner and the third president of the U.S. He called for science to determine the obvious “supremacy” of the white people, which was regarded as “an extremely important stage in the evolution of scientific racism”. (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Racism_in_the_United_States) The stronger the forces voices for abolition, the more the Southern white ruling class deliberately fostered race hatred to prevent poor whites from identifying with black slaves.

The system of repression was thus not only physical, but also psychological. In the South, white wage slaves were pushed to see themselves as superior to chattel slaves while they were co-opted into policing the slave system. The black slaves on the other hand “were impressed again and again with the idea of their own inferiority to ‘know their place’, to see blackness as a sign of subordination, to be awed by the power of the master, to merge their interest with the master’s, destroying their own individual needs”. (Howard Zinn, A People’s History of the United States; Chapter 2: “Drawing the Color Line”; https://www.historyisaweapon.com/defcon1/zinncolorline.html)

The emotional and physical traumas of slavery were devastating. Generations of slavery had deprived the black people of their identity, their own language and their traditional way of life. Most often they didn’t know their date of birth and their own name. Instead they identified with and were given the name of their slave-owner. The consequences of this dehumanisation were not remedied overnight with the abolition of slavery on 1 January 1863. The legacy of race-based chattel slavery produced distinct trauma over many generations of black people in the U.S.

Segregation as a form of neo-slavery of the black people

Despite the victory of the Union over the Confederation of the South, the Civil War did not mean the end of the exploitation, oppression and terrorising of black people in the Southern States. For when slavery officially was abolished - by the Thirteenth Amendment of Lincoln - various forms of “neo-slavery” ("Slavery by Another Name") and forced labour continued across the United States and its territories.

One of these forms was convict labour, taking the place of slavery with shocking force. A new set of laws, called the Black Codes, made it possible to criminalise previously legal activity for African Americans, such as violating the prohibition of vagrancy. After being arrested, they were compelled to work without pay for the same white slave plantation owners, in the coalmines of Alabama, or in the famous “chain gangs” for the development of massive road projects. They were also forced to function as strike-breakers in the Alabama coal miners’ strike of 1894.

After the Civil War black people were subjected to what was known as the Jim Crow laws, a brutal system of segregation and discrimination. Under these laws, black people were still treated as second class citizens just as under the regime of “Apartheid” in South Africa. Whites could beat, rob, or even kill black people at will for minor infractions, which they actually did on a large scale. Under Jim Crow the reign of terror was firmly established with the widespread evolution of white supremacist militias, such as the KKK. The South became a prison-like landscape wherein surveillance, punishment, and policing forced the black body into a constant state of furtiveness and fugitivity.

“The legal system of segregation protected and encouraged a parallel, supposedly ‘popular’ system (thanks mainly to the fanaticism of the white petty bourgeoisie) of aggression, collective killings, and systematic lynchings. The petty bourgeoisie, especially in the Southern States, but not only there, unleashed their destructive fury with metronome regularity to terrorise the proletarians of slave origin. (“Slavery and racism, tools of capitalist exploitation”; https://en.internationalism.org/content/16886/slavery-and-racism-tools-capitalist-exploitation). Actually the situation of the black people under segregation was just as precarious as under the regime of enslavement. Racism and the rejection of others is a characteristic of all class societies, but in the case of the U.S. it is embedded in the bowels of society.

The workers’ organisations fighting the segregation of black workers

It is clear that the working class in the U.S. faced great obstacles in its struggle for unity. In 1935 W.E.B Du Bois would write that “The theory of race was supplemented by a carefully planned and slowly evolved method, which drove such a wedge between the white and black workers that there probably are not today in the world two groups of workers with practically identical interests who hate and fear each other so deeply and persistently and who are kept so far apart that neither sees anything of common interest.” (Du Bois; “Black Reconstruction in America”; Cited in: A History of Reconstruction after the Civil War; 4 May 2019; https://brewminate.com/a-history-of-reconstruction-after-the-civil-war/)

The first attempt after the Civil War to close the gap between the white and the black workers came from Friedrich Adolph Sorge after the founding of the Central Committee of the North American section of the International Workingmen’s Association in December 1870. The American sections of the IWA defended the principle of racial equality, allowed black workers to participate in their rallies and set up a special committee to organize black workers into trade unions. In September 1871 the New York Section of the IWA organized a demonstration of 20,000 workers, including a company of black workers, supporting the combatants of the Paris Commune and demanding an eight-hour day.

In 1866 the first national union federation, the “National Labour Union” (NLU), was organised. Its founding convention unanimously urged the organisation of all workers into the unions: "all workingmen be included within its rank, without regard to race or nationality". The second convention, in 1867, already decided to integrate the demand for the abolition of the system of convict labour. The NLU gained the admiration of Karl Marx and after harsh debates it actually accepted black unions in 1869, but only in the form of separate unions that could be affiliated with the NLU.

In 1869 the African Americans, who were denied full access to the NLU, came together to form the Colored National Labor Union (CNLU). The CNLU welcomed all workers no matter what race, gender, or occupation. Isaac Myers, who was appointed as their president, stated that the CNLU was a “safeguard for the colored man”. And about the segregated groups he said: "for real success separate organization is not the real answers. The white and colored must come together and work together. (…) The day has passed for the establishment of organizations based upon color." (enacademic.com/dic.nsf/enwiki/3931900)

In the end, as both the CNLU and the NLU began to decline, they paved the way for the “Knights of Labor”.

The “Knights of Labour” became a mass organisation in 1881 (after developing from a “secret society” founded in 1869). Intended to overcome the limitations of craft unions, the organization was designed to include all those who toiled with their hands. Under the slogan, “an injury to one is the concern of all”, it unfurled the banner of workers’ unity and aspired to unite all wage-earners into a single organisation regardless of skill, race, or sex. The Knights organised tens of thousands of black workers, although not without a struggle against segregation within the organisation. Thus, it had to tolerate the segregation of assemblies in the South.

With these first efforts the unification of the struggle between the black and the white workers was still far from being achieved.

In the second part we will take a closer look at the theoretical and political struggle that took place in the political parties of the proletariat in the first two decades of the 20th century and how these parties, in particular the Socialist Party of America, were able to enrich and deepen the acquisitions developed since the AWL of Weydemeyer.

Dennis 23.1.21

del.icio.us

del.icio.us Digg

Digg Newskicks

Newskicks Ping This!

Ping This! Favorite on Technorati

Favorite on Technorati Blinklist

Blinklist Furl

Furl Mister Wong

Mister Wong Mixx

Mixx Newsvine

Newsvine StumbleUpon

StumbleUpon Viadeo

Viadeo Icerocket

Icerocket Yahoo

Yahoo identi.ca

identi.ca Google+

Google+ Reddit

Reddit SlashDot

SlashDot Twitter

Twitter Box

Box Diigo

Diigo Facebook

Facebook Google

Google LinkedIn

LinkedIn MySpace

MySpace