Submitted by ICConline on

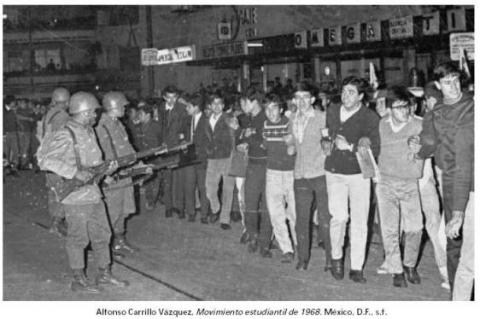

It's been estimated that between 300 and 500 people were massacred by the army on October 2 1968 on Tlatelolco Square. While the exact number, and still less the official list of the victims, is unknown to this day, the bourgeoisie has been able to exploit its own crimes. Some years after the massacre, the Mexican bourgeoisie began to consider this date as the starting point for the advance of democracy, as if the blood spilt had washed away all traces of this crime and consigned authoritarianism and repression to a distant past.

The speeches and commemorations around the fiftieth anniversary of the massacre have been used to re-launch the democratic campaign and, making the link with past elections, they pretend to show that the Mexican state has changed its face because democracy has taken power and even allowed for alternate governments. The bourgeoisie has also resumed its hypocritical wailing, letting its crocodile tears flow in order to try to distance itself from the crimes of 1968 and profit from the memory and from the still-present indignation among the exploited.

The demonstrations led by the students between July and October 1968 were, without any doubt, the expression of a strong social discontent which, even if their claims were limited by a desire for "democratic freedoms"[1] and even if the political scene was occupied by a heterogeneous social mass, had a certain continuity with the combative spirit re-awakened by the strikes of the rail workers in 1958 and the doctors in 1965. This movement didn't succeed in moving onto proletarian ground, or in raising demands belonging to the working class, but it did succeed in deploying and arousing strong forces of solidarity. That's why, 50 years after the events and the massacre, it is necessary to reflect on this by trying to go beyond the lack of conscience displayed by the Mexican state in its "celebration"[2] of the Tlatelolco massacre and the campaign of mystification created by the bourgeoisie through its "intellectuals" and its left political apparatus.

What triggered the demonstration?

In 1968 the Mexican state said that the student mobilisations could be explained as an "imitation" of May 68 in Paris, and that it had been incited by "foreign infiltration". A month before the government of Diaz Ordaz carried out the massacre against the students, the official trade union, CTM, repeated this idea: "Foreigners and bad Mexicans acting as active agents for communism, used the relatively unimportant scuffles of two small groups of students in order to launch a serious attack against the regime and the institutions of the country, adopting tactics similar to those adopted by extremists of these tendencies in other events and very recently in the outbursts in Paris..." (Manifesto to the Nation, September 2, 1968). Although there really was a global tendency towards social agitation influenced by the Paris demonstrations, it's false to suggest that these demonstrations were developed as no more than a sort of "fashion".

It was the return of the economic crisis onto the world scene which led to the workers' response of May 68[3] and it's the same trigger which opened the perspective for workers' responses in Italy (1969), Poland (1970-71), Argentina (1969) and even in Mexico which, without being a source of workers' mobilisation, aroused wide-scale social discontent.

It was also true that in the framework of the Cold War the dominant and competitive imperialist factions (the US and the USSR) used espionage and conspiracies, but up to now there's been no evidence that the USSR was implicated and still less the Cuban state, which had finalised an agreement with Mexico not to give its support to any opposition group[4]. It was similar for the "Communist Party", the Stalinist PCM which, although it was a pawn of the USSR, hadn't the strength or sufficient presence to lead the demonstrations.

On the other hand, the United States was keeping an eye on its "back-yard" and took an active part in the repression[5] during these years as during the whole of the Cold War.

In order to explain the origins of these demonstrations and the strength that they showed, it's necessary to go beyond the accusations of the government, but also to go deeper than the simplistic arguments about a "generational conflict" or an absence of "democratic liberties".

The students, as a social mass made up of diverse social classes but in which petty-bourgeois ideology dominates, were certainly held back by their illusions in democracy[6]. But another element pushed these students, who were often of proletarian origins, towards politicisation: the growing uncertainty that they felt in the future that awaited them. The promise of "social promotion" that the industrialisation of the 1940's to the 60's offered to the university students more and more clearly appeared as a come-on, given that, although capitalist profits increased, the life of workers got no better and threatened on the contrary to get worse under the pressure of the re-emergence of the world economic crisis which had already begun to make itself felt. But even more than this uncertainty, the repression of the state against the protests of workers claiming higher wages exacerbated the anger. Time and again bullets and prison were the responses of the state against the workers: the miners of Coahuila (1950-51), the rail-workers’ strikes (1948-58), teachers (1958) and doctors (1965). It was evident that even while increasing the rhythm of production, capitalism was not able to offer lasting reforms to a new generation.

In these conditions, the demonstrations were fed by the courage and indignation of the workers who, in the preceding years had also been hit by state repression.

Democratic hopes sterilise the strength of solidarity

From the 1940's to the 70's, the Mexican bourgeoisie unleashed an intense propaganda in order to make it known that industrialisation, the motor of economic growth and the stability of prices, would ameliorate the quality of life of the active population. In this process of industrialisation, the state played a fundamental role in taking responsibility for direct investments and supporting private capital through the sale, often underpriced, of energy resources, but above all through a policy of wage controls combined with subsidies for goods consumed by the workers. With these measures it presented itself as the "welfare state" while reducing the cost of labour for business, thus favouring the growth of capitalist profits. In the process of industrialisation there was a growing need for qualified workers, hence the state’s expansion of enrolment in the universities and the higher education schools. This increased the number of students of proletarian origin, thus making these institutions poles of social tension.

In this sense, the student movement in Mexico 1968, organised within the National Strike Committee (CNH), represented an important force, but structured around oppositional visions which never went beyond the stage of democratic demands it wasn't able to free itself from its links with nationalist ideology. However there was a certain class instinct which had germinated in the heat of the demonstrations and which pushed the young students to aim to meet up with the workers through the continued presence of the "information brigades"[7] in the industrial areas and workers' quarters. They thus succeeded in awakening a force of solidarity among the workers, but this potential social force was contained and cancelled out through the CNH’s lack of political perspectives.

Only the working class has an alternative to capitalism

From the first demonstrations of the student movement at the end of July 68, the granaderos riot police and regular police units acted with great ferocity. Mexican Chief of Police, General Luis Cueto, justified the repression in a press conference, saying that it was: "a subversive movement" which was tending "to create an atmosphere of hostility to our government and country on the eve of the XIX Olympic Games" (El Universal, July 28, 1968).

A period of continued street fighting thus opened up during the course of which the riot police were outnumbered. The army was then called into action and unleashed its repression. From the first days of the protests the army attacked with such savagery that on the night of July 30, it fired a bazooka at a school.

As the police and the army intensified the ferocity of their interventions, solidarity among the workers grew but it didn't take an organised form that could stamp its presence on the social scene.

The sympathy of the workers was demonstrated by their individual presence or in small groups joining the street protests. It was the same workers who, in the previous years, had already suffered repression for giving their support or direct participation to the social movements. Attempts were also made to openly express their solidarity with the students: on August 27, doctors at the General Hospital organised a strike in solidarity. The next day, municipal workers of the capital, forced to participate in an official action aiming to discredit the protesters, spontaneously rejected the government's move, by chanting "we are sheep" making it clear that they were obliged to be there and thus undermining the wished-for participation in this demonstration; they were then vigorously attacked by the riot police.

The student movement succeeded in arousing sympathy and solidarity and although numerous groups had shouted in the streets and painted on the walls "We don't want the Olympic Games, we want revolution", the truth is that these movements went forward without any real perspective. This is not because of a "strategic error", but because of the absence of the working class as a class on the social scene. It's not enough to be present individually or expressing solidarity in an isolated way, that is only formally occupying the social ground while leaving one's own political perspectives to one side. In 1968, although great numbers of the students were of proletarian origin and although the workers themselves showed their sympathy towards them, the proletariat did not find itself as an organised and conscious force able to confront capitalism.

The Tlatelolco massacre is a product of capitalism

By September, the response of the state became more and more aggressive. The army occupied the buildings of the UNAM on the 18th, reporting back on the political activity of the IPN[8] and the quarters around them, and the reason for this was that four days later the buildings of the polytechnic school were attacked. There were violent conflicts during this period in which solidarity again developed with a remarkable presence integrating school students and with the strengthened support of the population of the area...The massacre was being prepared.

On October 2nd, at the end of a demonstration on Tlatelolco Square, military and paramilitary squadrons attacked the students, showing in its naked form what the domination of capitalism meant.

The savagery of this response by the state is often presented as "a moment of madness" by the then Secretary of the Interior, Luis Echeverria, feeding the paranoia of the President Diaz Ordaz, but the brutality of this repression was neither accidental, nor the result of one pathological individual, it was part of the essence of capitalism. One of the main supports of the state is its repressive apparatus. To reflect on this properly we shouldn't forget that as long as capitalism exists, massacres like this one of 50 years ago will continue.

State violence is not a problem of the past, it is part of the very essence of capitalism, as Rosa Luxemburg had already analysed: "Violated, dishonoured, wading in blood, dripping filth – there stands bourgeois society. This is it [in reality]. Not all spic and span and moral, with pretence to culture, philosophy, ethics, order, peace, and the rule of law – but the ravening beast, the witches’ Sabbath of anarchy, a plague to culture and humanity. Thus it reveals itself in its true, its naked form" (The Crisis of Social Democracy, 1916).

Although the bourgeoisie does have a need to ideologically justify its existence as a dominant class and present its system as a perfect expression of democracy, the truth is that it bases this existence on exploitation, which involves the permanent use of violence and terror and which it uses on a daily basis in order to maintain its power and its domination; bloody repression is also a part of its way of life.

Tatlin for Revolucion Mundial, Mexican section of the ICC, September 2018

[1] The six inoffensive and somewhat naive points claimed by the National Strike Committee (CHN) were:

- Freedom for political prisoners;

- Resignations of Generals Luis Cueto Ramirez and Raul Mendiola;

- Disbanding of the grenaderos, the special police units used against the struggle;

- Abrogation of Articles 145 and 145 (2) of the Penal Code (dealing with subversion and social agitation);

- Compensation for the families of the dead and wounded caused by the repression;

- Going after and arresting those within the police and the special forces of the army responsible for the repression.

[2] In this pretentious manner, the bosses of the university have proudly announced that they've planned a series of commemorative events beginning October 2, during the course of which they will spend 37 million pesos (about 2 million dollars).

[3] See our article "Fifty years since May 68" and "May 68 and the revolutionary perspective" parts one and two on our internet site.

[4] Jose Luis Alonso, a Mexican guerillero exiled to Cuba in the 1970's, declared in an interview: "Three days after our arrival (in Cuba) Manuel Pineiro, Cuban Information Minister, read a statement to us: "(...) The first condition for admission to the territory (is that) there will be no guerrilla formation in the framework of the priority given to the respect for the good relations between Mexico and Cuba..." El Universal, May 22, 2002. In the same vein is the witness of Alfredo Campa who said: "We welcome those who come but we give priority to our cordial relations with the Mexican government..." (Proceso, May 4, 1996).

[5] The ex-CIA agent, Philip Agee, in his book Inside the Company: CIA Diary named the direct collaborators with the CIA as the Mexican presidents Lopez Mateos, Diaz Ordaz and Luis Echeverria, but also members of the political police like Gutierrez Barrios and Nazar Haro.

[6] That was the motive for the speech at the time by Barros Sierra, Rector of the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM), in which he called for the defence of the Constitution, autonomy and freedom of expression while appealing to nationalist sentiments by lowering the flag to half-mast and singing the national anthem. This was generally used as a reference by the student movement of July 1968 in Mexico.

[7] Already in 1956, on the backs of the rail and teachers' strikes, the "Information Brigades" took a variety of forms but were clear elements of the self-organisation of the students which included reaching out to workers by going directly to factory gates, schools and markets. They organised and sometimes appropriated transport for the distribution of leaflets and facilitated open spaces in the streets for spontaneous discussion and mass meetings. See: Rebel Mexico: Student Unrest, Authoritarian Political Culture During the Long Sixties by Jaime M. Pensano.

[8] The Autonomous National University of Mexico, (UNAM) and the National Polytechnic Institute (IPN) are the principal higher education centres of the public sector.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us Digg

Digg Newskicks

Newskicks Ping This!

Ping This! Favorite on Technorati

Favorite on Technorati Blinklist

Blinklist Furl

Furl Mister Wong

Mister Wong Mixx

Mixx Newsvine

Newsvine StumbleUpon

StumbleUpon Viadeo

Viadeo Icerocket

Icerocket Yahoo

Yahoo identi.ca

identi.ca Google+

Google+ Reddit

Reddit SlashDot

SlashDot Twitter

Twitter Box

Box Diigo

Diigo Facebook

Facebook Google

Google LinkedIn

LinkedIn MySpace

MySpace