Submitted by ICConline on

2pm-6pm, November 24th, May Day Rooms, 88 Fleet Street, EC4Y, 1DH

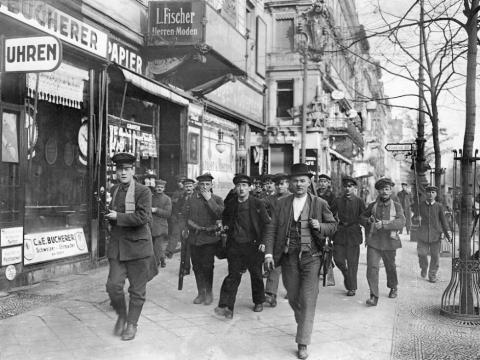

On November 4 1918 the sailors of Kiel on the Baltic coast mutinied, refusing the order to engage in yet another futile naval battle. Faced with the threat of brutal repression against the sailors, the workers of Kiel responded with a massive strike movement. Within days armed workers’ and soldiers’ councils were springing up all over Germany. This revolt spelt the end of the imperialist slaughter: the bourgeoisies of the world, who had been at each others’ throats for four long years, now united to face a bigger threat: the extension of the proletarian revolution from Russia to the most industrialised countries in Europe. In December the revolutionary groups who had opposed the war came together to form the Communist Party of Germany (KPD), which stood for the overthrow of the bourgeoisie and the political power of the councils.

Germany was to be the theatre of a whole series of major class confrontations for the next five years. But the great hope that a Soviet Germany would break the isolation of the proletarian fortress in Russia was never to materialise. The German workers faced a far more sophisticated ruling class than their Russian comrades, a bourgeoisie that showed itself to be highly skilled in diverting the revolution towards false goals and in defeating the centres of proletarian resistance one by one.

Thus as soon as the threat of revolution took shape, the bourgeoisie understood the need to jettison the Kaiser, bring the war to an end, and call on the loyal services of the “workers’ party”, the German Social Democracy, the majority of which had already come to the aid of the ruling class by throwing its energies into the national war effort. The social democrats still enjoyed the confidence of a large part of the German working class and they were able to act inside the councils with the aim of persuading them to hand over power to the newly “democratic” capitalist state. But the bourgeoisie also understood the need to provoke premature uprisings by different sections of the working class – a strategy employed with tragic results in Berlin in January 1919, which resulted in the massacre of thousands of workers and revolutionaries, including Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Liebknecht.

The defeat of the revolution in Germany, and the stemming of the revolutionary tide in numerous other countries, was to have catastrophic consequences for humanity: the degeneration and demise of the revolution in Russia, the rise of Stalinism and Nazism, the march towards the second imperialist world war.

A century later, the German revolution has almost been written out of history. It is still in the interests of our rulers to present the revolution in Russia as a purely Russian affair and to pretend that the world revolution was and is an idle dream. And yet the revolution in Germany showed that it was indeed a possibility, despite its failure. It is up to us to draw its principal lessons for future revolutionary movements of the working class, and this will be the main focus of the meeting.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us Digg

Digg Newskicks

Newskicks Ping This!

Ping This! Favorite on Technorati

Favorite on Technorati Blinklist

Blinklist Furl

Furl Mister Wong

Mister Wong Mixx

Mixx Newsvine

Newsvine StumbleUpon

StumbleUpon Viadeo

Viadeo Icerocket

Icerocket Yahoo

Yahoo identi.ca

identi.ca Google+

Google+ Reddit

Reddit SlashDot

SlashDot Twitter

Twitter Box

Box Diigo

Diigo Facebook

Facebook Google

Google LinkedIn

LinkedIn MySpace

MySpace