World War I - Special Issue

- 1697 reads

100 years of capitalist decadence

- 3730 reads

For a century now, humanity has stood at a crossroads in its history. Already in the 19th century the working class starkly outlined this historical watershed in the expression: "socialism or barbarism". The lucid marxist analysis revealed and expressed in this slogan cannot however be reduced to an empty slogan. Hence we want here to insist briefly on its historical importance and depth.

For a century now, humanity has stood at a crossroads in its history. Already in the 19th century the working class starkly outlined this historical watershed in the expression: "socialism or barbarism". The lucid marxist analysis revealed and expressed in this slogan cannot however be reduced to an empty slogan. Hence we want here to insist briefly on its historical importance and depth.

When we look at the human species' distant, obscure beginnings, we cannot help but be astounded at the immense steps forward that have marked mankind's emergence from the animal realm and marked its development since then: language, dance, art, architecture, the production of an immense wealth of material goods, and the ability to create a wealth and diversity of cultural, moral, and intellectual needs – all this represents a historical acceleration which takes the breath away.

Yet, when we focus our attention on the different epochs of human history, we must also acknowledge that mankind's development has never been a smooth progression. Still less has this been the case since the emergence of class society and the first great civilisations, all of which have long disappeared: only a very few of them have been able to transform themselves into something new. History reveals to us many epochs of cultural regression, the loss of skills and knowledge, generally accompanied by moral stultification and a brutalisation of human relationships.

The foundation of man's progress lies in his ability to transform nature with a view to the satisfaction of his own needs, and in the first place of his material needs, through the improvement and development of his tools and techniques – what Marx called "the productive forces". Fundamentally, it is the degree of development of these productive forces, and of the division of labour that they imply, which determine the way that society is organised to put them into operation: the "relations of production". When the framework provided by these relations allows the development of the productive forces, then society flourishes, not just on the material but also on the moral and cultural levels. But when the relations of production become a barrier to the continued development of the productive forces, then society undergoes repeated and worsening convulsions: it is threatened with a return to barbarism. To take just one historical example: one of the pillars of the Roman Empire was the exploitation of slave labour, especially in agriculture. The appearance of new farming techniques which could not be put into operation by producers whose status was lower than cattle was one of the causes of the Empire's decadence and final collapse.

The steps forward achieved by human culture,1 from the Neolithic revolution to the Renaissance, the emergence of humanism, and the Russian revolution, appear to us today as a grandiose prelude to the world revolution. These giant strides of human culture have always been the product of long periods of struggle, where new social relationships overcame and replaced the old. Today, they carry us towards a new leap forward: socialism, the first conscious and worldwide socialisation of the human species! Marxism, the theory that the proletariat adopted to light the way in its struggle against capitalism, is able to study this history with lucidity, free from mystification, and to recognise its major tendencies. This has nothing to do with crystal-ball gazing. We cannot predict when, or even whether, the world revolution will take place. What we can do is to understand in depth – and defend against all comers, including the incomprehension of some revolutionaries – the immense historical importance of capitalism's entry into its decadence. For 100 years, we have been faced with an alternative which can be summed up thus: either we succeed with the next social and cultural leap forward to socialism, or we fall back into barbarism.

The gravity of this alternative is greater than ever before in history, because today the growth in the contradictions between the productive forces and the relations of production has reached a point where it threatens humanity not just with social and cultural decline, but with complete destruction. For the first time in history, a mode of production's decadence is a menace for the very survival of the human species. Yet at the same time, it bears with it immense, historic possibilities for its future development: the beginning of humanity's truly conscious history.

The capitalist model of socialisation is the most successful in human history. Capitalism has absorbed – when it has not simply destroyed – all previous social and cultural milieux, and has for the first time created a worldwide human society. Its basic form of exploitation is wage labour, which makes possible the appropriation and the accumulation of surplus labour, as well as the unpaid appropriation of the enormous productive capacity created by associated, socialised labour. This is what explains the unparalleled technical and scientific explosion which is part and parcel of capitalism's rise. But one of capitalist socialisation's specificities is that it is carried out unconsciously. It is determined by laws which – although they are the expression of given human social relationships based on the exchange of labour power for wages, between the producers and the owners of the means of production – appear to be "natural" and "unchangeable", and so beyond the reach of human will. In this mystified – reified – view of reality, where human beings and the relations between them have become mere objects, the enormous increase in material resources and productive power appears as the product of capital rather than of human labour. Capitalism set out to conquer the world, but it turns out that the world is round. A world market has been created (on the ruins of alternative forms of production, like the textiles of China, India, or the Ottoman Empire for example). The success of the capitalist mode of production is a progressive step in human history; nonetheless for the vast majority of the population at the heart of capitalism the industrial revolution meant the destruction of previous ways of life and ferocious exploitation, while in much of the rest of the world it meant famine, epidemics and slavery. Capitalism is undoubtedly the most modern form of exploitation, but in the end it is every bit as parasitic as its predecessors. To keep the machine of accumulation going, capitalist socialisation demands ever more raw material and markets, and must constantly dispose of a reserve of human beings forced to sell their labour power to survive. This is why its victory over previous modes of production meant the ruin and starvation of the previous producers.

Capitalism presents itself as the aim and apogee of human development. If we are to believe its ideology, there is nothing beyond capitalism. But this means that capitalist ideology must hide two things: first, that historically capitalism is largely dependent on an environment and relations of production outside itself; second, that capitalist socialisation, like all the social forms that have preceded it, is only a stage in the process of humanity's coming to consciousness. The driving force of capitalist accumulation constantly creates internal contradictions which erupt in crises. During capitalism's ascendant phase, these crises were overcome by the destruction of excess capital and the conquest of new markets. With the new equilibrium thus achieved came a further extension of capitalist social relations – but once the world market had been shared out among the central capitalist powers the limits of this extension were reached. At this point, the great nation states can only pursue their world conquest at each other's expense. Since all the cake has been shared out, each can only increase his share by taking from the others.

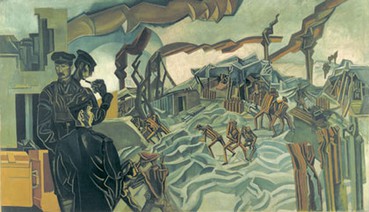

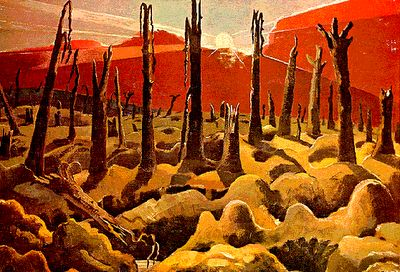

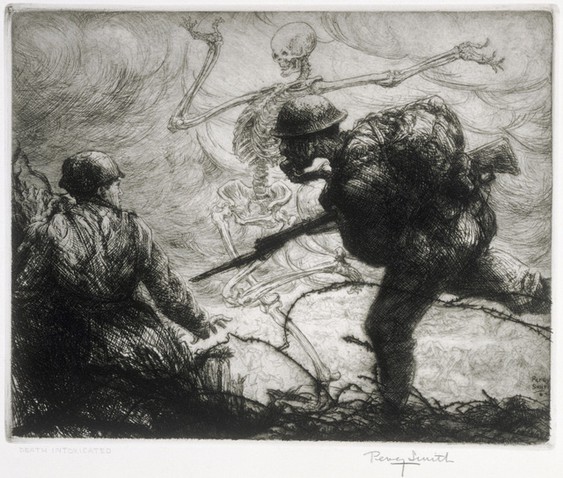

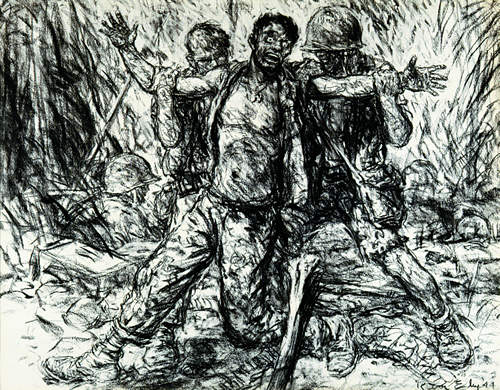

The nation states plunge into an arms race and hurl themselves at each others' throats in the First World War. In a world wide slaughter, the productive forces chained in by historically obsolete relations of production are transformed into a destructive force of enormous power. With capitalism's entry into decadence, warfare becomes a matter of equipment, and subjects the best part of production to military needs. The blind machine of annihilation drags the whole world down into the abyss.

Well before 1914, the left wing of the Socialist International, the revolutionary forces around Rosa Luxemburg and Lenin, fought with all their strength against the threat of imperialist war. Living marxism – the only real marxism – which is not enclosed in dogmas and formulae supposedly valid for all time, realised that this was not just another war between the nations like those before it, but that it marked the entry of capitalism into its decadent phase. The marxists knew that we were then, as we still are today, at a historical crossroads which threatens for the first time to become a struggle for the very survival of the human species. Capitalism's entry into decadence 100 years ago is irreversible, but this does not mean that the productive forces have come to a halt. In reality, these forces are so enchained and compressed by the logic of capitalist exploitation that society's development is dragged down into an ever more barbaric maelstrom. Only the working class can give history a different direction and build a new society. We have seen just what capitalism's unadulterated brutality is capable of after the defeat of the revolutionary upsurge in the years 1917-23. The course towards a new world war was opened, men reduced to ciphers, shut up in camps destined to murderous exploitation or plain extermination. Stalinist mass murder was surpassed by the annihilating madness of the Nazis; nor did the "civilised" ruling classes intend to miss the festivities of barbarism: the "democratic" atom bombs wiped two Japanese cities from the map and inflicted hideous suffering on the survivors.

The state capitalist machine may have learnt from history to the point of avoiding its own self-destruction – the bourgeois class will not simply commit suicide and abandon the historical stage to the proletariat – but only the return of the working class after 1968 offers any guarantee against a new course towards war. However, if the working class has proven capable of barring the road to a new world holocaust, it has not so far been able to impose its own perspective. In this situation, where neither of its two determining classes are capable of imposing a decisive response to an irreversible and ever deeper economic crisis, society is more and more rotting where it stands; a growing social decomposition makes it ever more difficult for the working class to achieve a clear awareness of its historical perspective – a historical perspective which a century ago was widely shared in the workers' ranks.

One hundred years ago, the working class faced a gigantic historic task, and so it still does today. The class of associated labour as such bears in itself the whole of human history: it is the central class in the struggle for the abolition of classes, and it must rise up against this barbarism. In the struggle against capitalism's nihilistic and amoral barbarity, the working class is the incarnation of a humanity become conscious of itself. It is the productive force of the future still in chains. Within it lies the potential for a new leap forward in human culture.

In the struggle against capitalism's entry into decadence, a whole generation of revolutionaries worldwide stepped forward, to set against capitalism's perverted and reified socialisation the conscious association of the working class, guided by the beacon of the Communist International.

With the Russian revolution, it took in hand the struggle for world revolution. For us today, one hundred years later, this great task of taking up our responsibilities for humanity's future remains an electrifying prospect. Even in the face of general stultification, a moral indignation arises in the heart of the working class, which gives us our bearings today. The working class suffers with the rest of humanity under the burden of decadence. Atomisation and the absence of perspective for the future attack our very identity. In the confrontations to come the working class will show whether it is capable of becoming conscious once again of its historical duty.

In the sweep of history, it is only a short step from moral indignation to the politicisation of an entire generation. A new leap forward in the history of human culture is both possible and vital. This is what living historical experience tells us.

ICC

1It should be clear that when we use the term "culture" here, we do so in the scientific sense, englobing the whole production of human society: technical and material of course, but also artistic, organisational, philosophical, moral, etc.

Historic events:

- World War I [1]

Heritage of the Communist Left:

Rubric:

1914: how the bloodletting began

- 4943 reads

2014: a year of forgetting

Even today the war that began in August 1914 goes by the name of the Great War, despite the fact that the Second World War that followed it in 1939 killed more than twice as many people, and despite the fact that the unending worldwide warfare since 1945 has been responsible for even more death and destruction than World War II.

Even today the war that began in August 1914 goes by the name of the Great War, despite the fact that the Second World War that followed it in 1939 killed more than twice as many people, and despite the fact that the unending worldwide warfare since 1945 has been responsible for even more death and destruction than World War II.

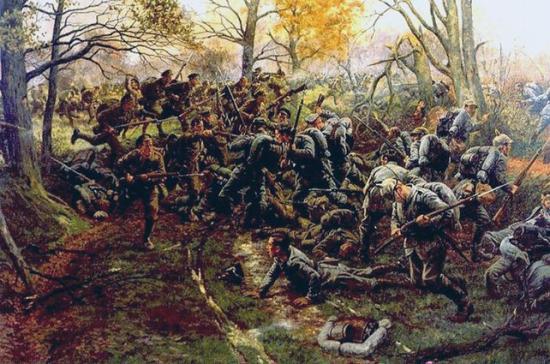

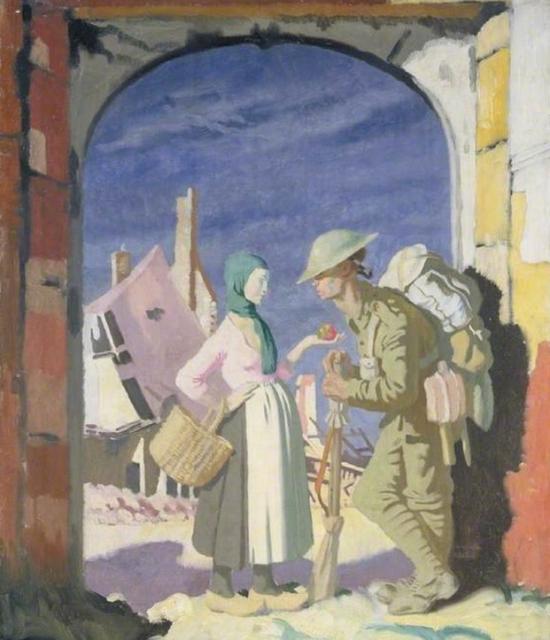

To understand why 1914-18 is still the “Great War”, we need only visit any village in France, even the most isolated lost in its Alpine pastures, and read the roll-call of the dead on the war memorials: whole families are there – brothers, fathers, uncles, sons. These mute witnesses to horror stand not just in the towns and villages of the European belligerent nations, but even on the other side of the world: the memorial in the tiny settlement of Ross on the Australian island of Tasmania bears the names of 16 dead and 44 survivors, presumably of the Gallipoli campaign. Humanity was no stranger to war, but 1914 was the first time it had been involved in World War.

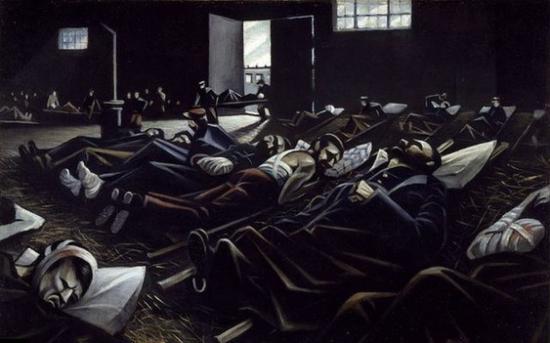

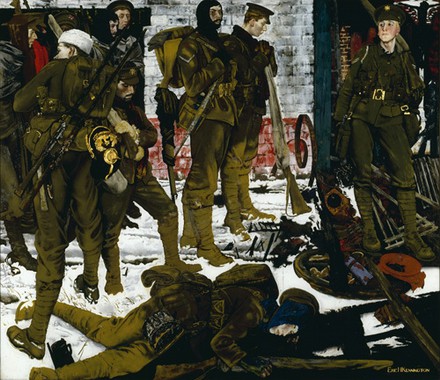

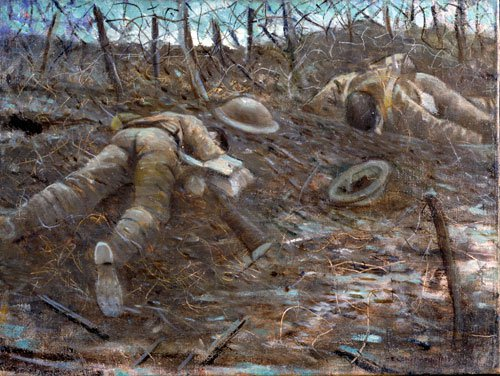

For two generations after the war ended, 1914-18 was synonymous with senseless carnage, driven by the uncaring blind stupidity of an aristocratic ruling caste, and the unbridled greed of imperialists, war profiteers and arms manufacturers. Despite all the official ceremonies, the laying of wreaths and (in Britain) the symbolic wearing of poppies on Memorial Day, this view of World War I passed into popular culture in the belligerent nations. In France, Gabriel Chevalier's autobiographical novel of life in the trenches Fear (La Peur), published in 1930, had an enormous success, to the point where the book was briefly banned by the authorities. In 1937, Jean Renoir's anti-war movie The Grand Illusion (La Grande Illusion), played continuously at the Marivaux cinema in Paris from 10 in the morning till two at night, beating every previous box office record: in New York it played for 36 weeks.1

In 1920s Germany, George Grosz’s satirical cartoons lambasted the generals, politicians and profiteers who had done well out of the war. The war veteran Erich Maria Remarque’s All quiet on the Western Front (Im Westen Nichts Neues) was published in 1929 and 18 months later had sold 2.5 million copies in 22 languages; the 1930 film version by Universal Studios was a smash hit in the USA, winning an Oscar for best picture.2

In its disintegration, the Austro-Hungarian empire bequeathed to the world one of the greatest anti-war novels: Jaroslav Hašek's The good soldier Svejk (Osudy dobrélo vojáka Švejk za světové války), published in 1923 and since translated into 58 languages – more than any other work in Czech.

In its disintegration, the Austro-Hungarian empire bequeathed to the world one of the greatest anti-war novels: Jaroslav Hašek's The good soldier Svejk (Osudy dobrélo vojáka Švejk za světové války), published in 1923 and since translated into 58 languages – more than any other work in Czech.

The revulsion at the memory of World War I survived the still greater bloodletting of World War II. Compared to the horrors of Auschwitz and Hiroshima the barbarity of Prussian militarism and Tsarist oppression – not to mention French or British colonialism – which had provided the justification for war in 1914, almost paled into insignificance, making the slaughter in the trenches seem still more monstrous and absurd: World War II could be portrayed as, if not exactly a “good war” then at least as a just and necessary war. Nowhere is this contradiction clearer than in Britain, where a stream of heroic “good war” movies (Dambusters in 1955, 633 Squadron in 1964, etc) filled the cinema screens in the 1950s and 60s, while at the same time the anti-war writings of war poets Wilfred Owen, Siegfried Sassoon, and Robert Graves were required reading for 15-year old school students.3 Perhaps the finest composition of Benjamin Britten, the 20th century's best known British composer, was his War Requiem (1961) which set Owen's poetry to music, while in 1969 two very different films hit the silver screen: Battle of Britain, in the patriotic vein, and the viciously satirical Oh What a Lovely War!, which succeeded in creating a musical denunciation of the First World War using original soldiers' songs from the trenches.

Two generations later, we stand on the eve of the 100th anniversary of the outbreak of war on 4th August 1914. Given the symbolic importance of round number anniversaries, and still more of centenaries, preparations are under way to commemorate (“celebrate” is perhaps hardly the word) the war. In Britain and France, budgets of tens of millions (euros or sterling) have been set aside; in Germany, for obvious reasons, preparations are more discreet and have no official government benediction.4

“He who calls the piper pays the tune”, so what are the ruling classes getting for the tens of millions they have budgeted to “commemorate the war”?

Look at the websites of the organisations responsible for the commemoration (in France, a special body set up by the government; in Britain – appropriately – the Imperial War Museum) and the answer seems clear enough: they are buying one of history's most expensive smokescreens. In Britain, the Imperial War Museum is devoting itself to bringing together the stories of individuals who lived during the war and turning them into podcasts.5 The Centenary Project's website (1914.org) offers such crucial events as the Museum display of “JRR Tolkien's First World War revolver” (we're not joking – presumably the aim is to cash in on the success of the Lord of the Rings movies); the commemoration of a Surrey war playwright, the London Transport Museum collecting World War I bus stories (seriously!); Nottingham City and County's “major program of events and activities (...) will highlight how the conflict was a catalyst for huge social and economic change in the communities of Nottinghamshire”. The BBC have produced a “groundbreaking” documentary: “The First World War from above” – photos and film footage taken from aircraft and observation balloons. The pacifists will get a look-in with commemorations of conscientious objectors. In short, we are going to be drowned in an ocean of detail, and even of trivia. According to the Imperial War Museum's Director-General “Our ambition is that a lot more people will understand that you can’t understand the world today unless you understand the causes, course and consequences of the First World War”6 and we would agree 100%. But the reality is that everything possible is being done – including by the honourable Director-General – to prevent us from understanding those causes and consequences.

In France, the centenary website carries the impeccably official “Report to the President on commemorating the Great War” dated September 20117 which begins with these words from General de Gaulle's speech at the 50th anniversary in 1964: “On 2nd August 1914, the day mobilisation was announced, the whole French people came to their feet as one. This had never been seen before. Every region, every district, every category, every family, every living being, suddenly found common cause. In an instant, political, social, religious quarrels that had divided the country, disappeared. From one end of the nation to the other, words, songs, tears, and above all the silence, expressed a single resolve”. And in the report itself we read that “While the Centenary will provoke amongst our contemporaries dread at the mass slaughter and the immense sacrifices that were accepted, it will also send a shiver through French society, reminding us of the unity and national cohesion that the French displayed in the face of the trial of World War I”. It seems unlikely then, that the French ruling class intends to tell us anything about the brutal police repression of workers' anti-war demonstrations during July 1914, or about the infamous “Carnet B” (the government's list of socialist and syndicalist anti-militarist militants to be rounded up and interned or sent to the front at the outbreak of war – the British had their own equivalents), and still less about the circumstances in which anti-war socialist leader Jean Jaurès was assassinated on the very eve of the conflict, or about the mutinies in the trenches8...

As ever the propagandists can count on the support of the learned gentlemen of Academe to provide them with themes and material for their talk-shows and TV programmes. We will take just one example which seems to us emblematic: Cambridge University historian Christopher Clark's The Sleepwalkers, first published in 2012, published in paperback in 2013, and already translated into French (Les Somnambules) and German (Die Schlafwandler).9 Clark is an unashamed empiricist, And his Introduction sets out his intentions quite openly: “This book (...) is concerned less with why the war happened than with how it came about. Questions of why and how are logically inseparable, but they lead us in different directions. The question of how invites us to look closely at sequences of interactions that produced certain outcomes. By contrast, the question of why invites us to go in search of remote and categorical causes: imperialism, nationalism, armaments, alliances, high finance, ideas of national honour, the mechanics of mobilisation”. Missing from Clark's list of course is “capitalism”. Could capitalism as such generate war? Could war be not just “politics by other means” (to use von Clausewitz's famous expression), but the ultimate expression of the competition inherent in the capitalist mode of production? Oh no, no, no: perish the thought! Clark sets out then, to lay before us “the facts” on the road to war, and this he does with immense erudition and in enormous detail right down to the colour of the ostrich feathers on Archduke Franz Ferdinand's helmet on the day of his assassination (they were green). Had anyone bothered to note down the colour of his assassin Gavrilo Princip's underwear that day, it too would be in this book.

The book's length, its overwhelming mastery of detail, makes one huge omission all the more striking: despite devoting whole sections to “public opinion”, Clark has nothing whatever to say about the one part of “public opinion” that really mattered – the stand adopted by the organised working class. Clark cites extensively from newspapers like the Manchester Guardian, the Daily Mail, or Le Matin, and others long since deservedly forgotten, but not once does he cite Vorwärts or L'Humanité (the press respectively of the German and French Socialist Parties), nor La Vie Ouvrière, the quasi-official organ of the French syndicalist CGT,10 nor its Bataille Syndicaliste. These were not minor publications: Vorwärts was only one of the SPD's 91 dailies, with a total circulation of 1.5 million (by comparison, the Daily Mail claimed a circulation of 900,000),11 and the SPD itself was the largest political party in Germany. Clark mentions the SPD's 1905 Jena Congress and its refusal to call for a general strike in the event of war, but there is no mention of the anti-war resolutions adopted by the Socialist International's congresses at Stuttgart (1907) and Basel (1912). The only leader of the German SPD to merit a mention is Albert Südekum, a relatively insignificant figure on the right of the SPD who is given a walk-on part reassuring German Chancellor Bethmann-Hollweg on 28th July that the SPD will not oppose a “defensive” war.

On the struggle between left and right in the socialist and broader working class movement, there is silence. On the political combat of Rosa Luxemburg, Karl Liebknecht, Anton Pannekoek, Herman Gorter, Domela Nieuwenhuis, John MacLean, Vladimir Ilyich Lenin, Pierre Monatte and many others, there is silence. On the assassination of Jean Jaurès there is silence, silence, silence...

Clearly, the proletarians cannot rely on bourgeois historiography truly to understand the causes and consequences of the Great War. Let us then turn instead to two outstanding militants of the working class: Rosa Luxemburg, arguably the finest theoretician of the German Social-Democracy, and Alfred Rosmer, a stalwart militant of the pre-war French CGT. In particular, we will draw here on Luxemburg's Crisis in the German Social-Democracy12 (better known as the “Junius Pamphlet”), and on Rosmer's Le mouvement ouvrier pendant la Première Guerre mondiale13 (The workers' movement during the First World War). The two works are very different: Luxemburg's pamphlet was written in 1916, in prison (no privileged access to libraries and government archives for her, and the power and clarity of her analysis is all the more impressive for that); the first volume14 of Rosmer's work, where he deals with the period leading up to war, was published in 1936, and is the fruit both of his painstaking dedication to historical truth and his passionate defence of internationalist principle.

World War I: its importance and its causes

Some might ask whether it really matters. It was all a long time ago, the world has changed, what can we really learn from these writings from the past?

We would answer that understanding World War I is vital for three reasons.

First, because World War I opened a new historical epoch: we are still living in a world shaped by the consequences of that war.

Second, because the underlying causes of the war are still very much present and operational: there is an all too striking parallel to be drawn between the rise of Germany as a new imperialist power prior to 1914, and the rise of China today.

Finally – and perhaps most importantly, because this is what the government propagandists and the historians really want to hide from us – because there is only one force that can put a stop to imperialist war: the world working class. As Rosmer says: “the governments know very well that they cannot undertake the dangerous adventure of war - this war above all - unless they have behind them the virtually unanimous support of public opinion, and above all of the working class; to get it, they must deceive, dupe, mislead, excite”.15 Luxemburg quotes “the well-known words of [German Chancellor] Bülow: 'They are trying to put off the war chiefly because they fear the Social-Democracy.'”; she also quotes from General Bernhardi's Vom Heutigen Krieg: “when great, compact masses once shake off their leaders (...) then the army becomes not only ineffectual against the enemy, it becomes a menace to itself and to its leaders. When the army bursts the bands of discipline, when it voluntarily interrupts the course of military operation, it creates problems that its leaders are unable to solve”. And Luxemburg continues: “capitalist politicians and military authorities alike believe war, with its modern mass armies, to be a dangerous game. And therein lay for the Social-Democracy the most effectual opportunity to prevent the rulers of the present day from precipitating war and to force them to end it as rapidly as possible. But the position of the Social-Democracy in this war cleared away all doubts, has torn down the dams that held back the storm-flood of militarism (...) And so the thousands of victims that have fallen for months on battlefields lie upon our conscience”.16

The outbreak of generalised, world wide imperialist war (we are not talking here about localised conflicts, even major ones like the Korean or Vietnam wars, but about mass mobilisation of the proletariat in the heart of capitalism) is determined by two opposing forces: the drive toward war, toward a new division of the world among the great imperialist powers, and the struggle to defend their own existence by the working masses who must provide both the cannon fodder and the industrial army without which modern war is impossible. The Crisis in the Social-Democracy, and especially in its most powerful fraction, the German Social-Democracy – a crisis systematically ignored by the tame historians of Academe – is thus the critical factor that made war possible in 1914.

We will look at this in more detail in a later article in this series, but here we propose to take up Luxemburg's analysis of the shifting imperialist rivalries and alliances that drove the great powers inexorably into the bloodbath of 1914.

“Two lines of development in recent history lead straight to the present war. One has its origin in the period when the so-called national states, i.e., the modern states, were first constituted, from the time of the Bismarckian war against France. The war of 1870, which, by the annexation of Alsace-Lorraine, threw the French republic into the arms of Russia, split Europe into two opposing camps and opened up a period of insane competitive armament, first piled up the firebrands for the present world conflagration (...) Thus the war of 1870 brought in its wake the outward political grouping of Europe about the axes of the Franco-German antagonism, and established the rule of militarism in the lives of the European peoples. Historical development has given to this rule and to this grouping an entirely new content.

The second line that leads to the present world war, and which again brilliantly justifies Marx’s prophecy,17 has its origin in international occurrences that Marx did not live to see, in the imperialist development of the last twenty-five years”.18

The last 30 years of the 19th century thus saw a rapid expansion of capitalism throughout the world, but also the emergence of a new, dynamic, expanding and confident capitalism in the heart of Europe: the German Empire, which had been declared in Versailles in 1871 after France's defeat in the Franco-Prussian war, which Prussia entered as merely the most powerful of a multitude of German statelets and principalities, and emerged from as the dominant component of a new, united Germany. “It is obvious”, writes Luxemburg, “that this live, unhampered imperialism, coming upon the world stage at a time when the world was practically divided up, with gigantic appetites, soon became an irresponsible factor of general unrest”.19

By one of those quirks of history which allow us to symbolise a shift in the historical dynamic with a single date, the year 1898 witnessed three events which mark one such shift.

The first was the “Fashoda Incident”, a tense face-off between British and French troops for control of the Sudan. At the time, there seemed to be a real risk that France and Britain would go to war for the control of Egypt and the Suez Canal, and for dominance in Africa. Instead, the incident ended with an improvement in Franco-British relations which was formalised in the “Entente Cordiale” of 1904, and a growing tendency for Britain to back France against a Germany that both saw as a threat. The two “Moroccan crises” of 1905 and 191120 showed that henceforth Britain would block German ambitions in North Africa (though it was prepared to leave Germany some titbits: Portugal's colonial possessions).

The second event was Germany's seizure of the Chinese port of Tsingtao (today's Qingdao),21 which announced Germany's arrival on the imperialist stage as a power with world wide, not merely European aspirations – a Weltpolitik as it was called at the time in Germany.

Appropriately, 1898 also saw the death of Otto von Bismarck, the great Chancellor who had guided Germany through unification and rapid industrialisation. Bismarck had always opposed colonialism and naval construction, his main foreign policy concern being to avoid the emergence of anti-German alliances amongst other European powers jealous – or fearful – of Germany's rise. But by the turn of the century Germany had become a world class industrial power second only to the United States, with world class ambitions to match. Luxemburg quotes then Foreign Secretary von Bülow on 11th December 1899: “When the English speak of ‘a greater Britain’, when the French talk of ‘The New France’, when the Russians open up Asia for themselves, we too have a right to aspire to a greater Germany. If we do not create a navy sufficient to protect our trade, our natives in foreign lands, our missions and the safety of our shores, we are threatening the most vital interests of our nation. In the coming century the German people will be either the hammer or the anvil.” And she comments: “Strip this of its coastal defence ornamentation, and there remains the colossal program: greater Germany, as the hammer upon other nations”.

In the early 20th century, having a Weltpolitik meant having a world class navy. As Luxemburg points out very clearly, Germany had no immediate economic need for a navy: nobody planned to seize its possessions in China or Africa. A navy was above all a matter of prestige: to continue its expansion Germany had to be seen as a serious player, a power to be counted with, and for this a “first-class aggressive navy” was a prerequisite. In Luxemburg's unforgettable words, it was “a challenge not only to the German working class, but to other capitalist nations as well, a challenge directed to no one in particular, a mailed fist shaken in the face of the entire world...”.

The parallel between the rise of Germany at the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries, and that of China 100 years later, is obvious. Like Bismarck, Deng Xiaoping's foreign policy went to great lengths to avoid alarming both China's neighbours and the world hegemon, the United States. But with its rise to the status of second world economic power, China's prestige demands that it should be able, at a minimum, to control its maritime boundaries and protect its sea-lanes: hence its naval build-up, construction of submarines and an aircraft carrier, and recent declaration of an “Air Defence Identification Zone” covering the Senkaku/Diaoyu islands.

The parallel between Germany in 1914 and China today is not of course an identity, for two reasons in particular: firstly, Germany in the early 20th century was not only the world's second industrial power after the United States, it was also in the forefront of technical progress and innovation (as can be judged, for example, by the numbers of German Nobel prize winners and German innovation in steel, electrical machinery, and chemical industries); secondly, Germany could project military power globally in a way that China cannot, at least not yet.

And just as the United States today is bound to meet China's threat to its own prestige and to the security of its allies (Japan, South Korea and the Philippines in particular), so Britain could only see Germany's naval build-up as a threat, and an existential threat at that, directed against the vital artery of Channel shipping and its own coastal defences.22

Whatever its naval ambitions, however, the natural direction for a land power like Germany to expand, was towards the East, and specifically towards the decaying Ottoman Empire; this was all the more true when its ambitions in Africa and the Western Mediterranean were blocked by the British and French. Money and militarism went hand in hand, as German capital poured into Turkey,23 fighting for elbow room with its French and British competitors. A large share of this German capital went to financing the Baghdad railway: this was in fact a network of lines intended to link Berlin to Constantinople and then on to the south of Anatolia, Syria, and Baghdad, but also to Palestine, the Hejaz and Mecca. In a day when troop movements depended on railways, this would make it possible for a Turkish army, equipped with German guns and trained by German instructors, to send troops by rail to threaten both Britain's oil refinery at Abadan (Persia, modern Iran),24 and British control of Egypt and the Suez Canal: here again was a direct German threat to Britain's vital strategic interests. During much of the 19th century, the main security threat to the British Empire had been Russian expansion into Central Asia, bringing it to the border of Persia and posing a menace to India; but Russia's defeat by Japan in 1905 had dampened its Eastern ambitions such that an Anglo-Russian Convention in 1907 had – at least for a time – resolved disputes between the two countries in Persia, Afghanistan and Tibet. Germany was now the rival to be opposed.

Germany's Eastern policy necessarily gave it a strategic interest in the Balkans, the Bosphorus, and the Dardanelles. The fact that the route of the Berlin-Constantinople railway was planned to run through Vienna and Belgrade made control over Serbia, or at least Serbian neutrality, a matter of great strategic importance to Germany. This in turn could only bring it into conflict with a country which in Bismarck's day had been a bastion of autocratic reaction and solidarity, and hence Prussia and Imperial Germany's firm ally: Russia.

Ever since the reign of Catherine the Great, Russia had established itself (in the 1770s) as the dominant power on the Black Sea coast, displacing the Ottomans. Russian industry and agriculture's increasingly important Black Sea trade depended on free passage through the Bosphorus straits controlled by Constantinople, and Russian ambition looked to the Dardanelles and control over maritime traffic between the Black Sea and the Mediterranean (Russian designs on the Dardanelles had already led to war with Britain and France in the Crimea in 1853). Luxemburg sums up the dynamics within Russian society driving its imperialist policies: “On the one hand, the traditional tendencies of a conquest-loving Czardom, ruling over a mighty nation whose population today consists of 172 millions of human beings, demand free access to the ocean, to the Pacific Ocean on the East, to the Mediterranean on the South, for industrial as well as for strategic reasons. On the other hand, the very existence of absolutism, and the necessity of holding a respected place in the world-political field, and finally the need of financial credit in foreign countries without which Czarism cannot exist, all play their important part (…) But modern capitalist interests are becoming more and more a factor in the imperialist aims of the Czarist nation. Russian capitalism, still in its earliest youth, cannot hope to perfect its development under an absolutist regime. On the whole it has advanced little beyond the primitive stage of home industry. But it sees a gigantic future before its eyes in the exploitation of the nation’s natural resources (...) It is this hope, and the appetite for foreign markets that will mean increased capitalistic development even at the present time, that has filled the Russian bourgeoisie with imperialistic desires and led them to eagerly voice their demands in the coming division of the world’s resources”.25 Rivalry between Germany and Russia over control of the Bosphorus thus inevitably found its nexus in the Balkans, where the rise of nationalist ideology characteristic of developing capitalism, had created a situation of permanent tension and intermittent bloody warfare between the three new states broken off from the decaying Ottoman Empire: Greece, Bulgaria, and Serbia. These three countries fought a First Balkan War as allies against the Ottomans, then a Second Balkan War among themselves to re-divide the plunder from the First, especially in Macedonia and Albania.26

The rise of aggressive new nation states in the Balkans could hardly be a matter of indifference to the region's other decaying dynastic empire: Austria-Hungary. “Not the political expression of a capitalist state, but a loose syndicate of a few parasitic cliques, striving to grasp everything within reach, utilizing the political powers of the nation so long as their weakened edifice still stands”,27 Austria-Hungary was under constant threat from the ambitious new nations around it, all of which shared ethic populations with parts of the Empire: hence Austria-Hungary's annexation of Bosnia-Herzegovina, which was part of a constant concern to prevent Serbia from gaining access to the Mediterranean.

By 1914, the situation in Europe had developed into a lethal Rubik's cube, its different pieces so interlocked that moving one must necessarily displace all the others.

The wide-awake sleepwalkers

Does this mean that the ruling classes, the governments, did not know what they were doing? That – as the title of Christopher Clark's book The Sleepwalkers implies – they somehow walked into war by accident, that World War I was just some terrible mistake?

Not a bit of it. Certainly, the historical forces that Luxemburg describes, in what is probably the most profound analysis of the outbreak of war ever written, held society in their grip: in this sense the war was the inevitable result of interlocking imperialist rivalries. But historical situations call forth the men to match them, and the governments that took Europe, and the world, into war not only knew very well what they were doing, they did it deliberately. The years from the turn of the century to the outbreak of war had been marked by repeated war scares, each one more serious than the last: the Tangier Crisis in 1905, the Agadir Incident in 1911, the First and Second Balkan Wars. Each of these incidents brought the pro-war faction in each ruling class more to the fore, heightened the sense that war was anyway inevitable. The result was an insane arms race: German launched its naval construction programme and Britain followed suit; France increased the length of military service to three years; huge French loans financed the modernisation of Russian railways designed to carry troops to the Western Front, as well as the modernisation of Serbia's small but effective army. All the continental powers increased the number of men under arms.

Convinced as they increasingly were that war was inevitable, the question for the governments of Europe became simply a matter of “when?”. When would each nation's military preparedness be at its height compared to that of its rivals? Because this moment would be the “right” moment for war.

If Luxemburg saw a rising Germany as the new “irresponsible element” in the European situation, does this mean that the powers of the Triple Entente (Britain, France, Russia) were the innocent victims of German expansionist aggression? This is the thesis of certain “revisionist” historians today: not only that the struggle against German expansionism was justified in 1914, but that in essence 1914 is nothing but a precursor of the “good war” in 1939. This is undoubtedly the case, but the Triple Entente were anything but innocent victims and the idea that Germany was uniquely “expansionist” and “aggressive” is laughable if we compare the size of Britain's empire – the result of British expansionist aggression – with that of Germany: somehow this never seems to cross the minds of Britain's tame historians.28

In fact, the Triple Entente (Britain, Russia, France) had been preparing for years a policy of encirclement of Germany (just as the US developed a policy of encircling the USSR during the Cold War and is trying to do the same with China today). Rosmer demonstrates this with inexorable clarity, on the basis of the secret diplomatic correspondence among the Belgian ambassadors in the different European capitals.29

In May 1907, the ambassador in London writes that “It is obvious that official Britain is pursuing an underhand and hostile policy which tends towards the isolation of Germany, and that King Edward [ie Edward VII] has unhesitatingly put his own personal influence into the balance in favour of this idea”.30 In February 1909, we hear from the ambassador in Berlin: “The King of England asserts that the preservation of peace has always been his goal; he has repeated this over and over since he began his successful campaign to isolate Germany; but one cannot help remarking that world peace has never been in greater danger than since the King of England set about defending it”.31 From Berlin again, in April 1913 we read: “...the arrogance and contempt with which [the Serbs] receive the protests of the government in Vienna can only be explained by the support they expect from St Petersburg. The Serbian chargé d'affaires said here recently that his government would never have taken such risks, taking no account of Austria's threats, if it had not been encouraged by the Russian ambassador Mr Hartwig...”.32

In France, the conscious development of an aggressive chauvinist policy was perfectly clear to the Belgian ambassador in Paris (January 1914): “I have already had the honour to inform you that it is Messrs Poincaré, Delcassé, Millerand and their friends who have invented and put into practice the nationalist, jingoistic and chauvinist policy whose rebirth we are seeing today (…) I see here the greatest danger for European peace (…) because the attitude adopted by the Barthou government is, in my view, the determining cause of the increasing militarist tendencies in Germany”.33

The re-introduction by France of the three year military service was not a policy of defence, but a deliberate preparation for war. Here is the ambassador in Paris again (June 1913): “The cost of the new law will weigh so heavily on the population, the resulting expenses will be so exorbitant, that the country will soon protest, and France will be faced with the dilemma: either a climb-down which it could not tolerate or war in the short term”.34

How to declare war

Two factors entered into the calculations of statesmen and politicians in the years leading to war: the first was their estimation of their own and their adversaries' military preparedness, but the second – equally important, even in autocratic Tsarist Russia – was the need to appear to the world and their own populations, especially the workers, as the injured party, acting solely in self-defence. All the powers wanted to enter a war that had been started by someone else: “The game consisted in leading one's adversary into committing an act which could be used against him, or making use of a decision he had already taken”.35

The assassination of Franz Ferdinand which provided the spark that set off the war was hardly the work of an isolated individual: Gavrilo Princip fired the fatal shot, but he was only one of a group of assassins, themselves organised and armed by one of the networks organised by the ultra-nationalist Serbian groups “Black Hand” and Narodna Odbrana (“National Defence”), which formed almost a state within a state and whose activities were undoubtedly known to the Serbian government and in particular its Prime Minister Nicolas Pasič. Relations between the Serbian and Russian governments were extremely close, and it is certain that the Serbs would not have undertaken such a provocation had they not been assured of Russian support against an Austro-Hungarian reaction.

For the Austro-Hungarian government, the assassination seemed a chance too good to miss, to bring Serbia to heel.36 The police investigation had little difficulty pointing the finger at Serbia, and the Austrians counted on the shock provoked among Europe's ruling classes to gain support, or at least neutrality, when they attacked Serbia. In effect, Austria-Hungary had no choice but to attack, or humiliate Serbia: anything less would have been a devastating blow to its prestige and influence in the critical region of the Balkans, leaving it completely in the hands of its Russian rival.

The French government saw a “Balkan war” as the ideal scenario for their attack on Germany: if Germany could be forced into war in defence of Austria-Hungary, and Russia came to the defence of Serbia, then French mobilisation could be presented as a precautionary measure against the threat of German attack. Moreover, it was extremely unlikely that Italy, nominally an ally of Germany but with its own interests in the Balkans, would go to war to defend Austria-Hungary's position in Bosnia-Herzegovina.

Given the alliance ranged against it, Germany found itself in a position of weakness with Austria-Hungary, that “organised heap of decay” to use Luxemburg's words, as its only ally. The war preparations in France and Russia, the development of their Entente with Britain, led German strategists increasingly to the conclusion that war would have to be fought sooner rather than later, before their adversaries were fully prepared. Hence the remark of the Chancellor Bethmann-Hollweg that “Should the conflict [between Serbia and Austria-Hungary] spread, then it is absolutely necessary that Russia should bear the responsibility”.37

The British population was hardly likely to go to war to defend Serbia, or even France. Britain too needed “a pretext to overcome the resistance of a large part of its public opinion. Germany provided an excellent one, by launching its armies through Belgium”.38 Rosmer quotes Viscount Esher's Tragedy of Lord Kitchener to the effect that “The German invasion of Belgium, although it made no vital difference to the resolve already taken by [Prime Minister] Asquith and [Foreign Secretary] Grey, preserved the unity of the nation, if not the integrity of the government”. 39 In reality, British plans for an attack on Germany, prepared in concert with the French military for several years, had long intended to violate Belgian neutrality...

All the belligerent nations' governments thus had to deceive their “public opinion” into thinking that the war which they had prepared and deliberately sought for years, had been forced unwillingly upon them. The critical element in this “public opinion” was the organised working class, with its trade unions and Socialist Parties, which for years had stated clearly its opposition to war. The single most important factor that opened the road to war was therefore the betrayal of the Social-Democracy, and its support for what the ruling class falsely portrayed as a “defensive war”.

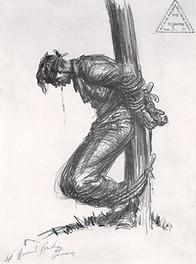

The underlying causes of this monstrous betrayal of Social-Democracy's most elementary internationalist duty will be the object of a future article. Suffice it to say here that the French bourgeoisie's claim today that the “political, social, religious quarrels that had divided the country, disappeared....in an instant” is a bare-faced lie. On the contrary, Rosmer's account of the days before the outbreak of war is one of constant working-class demonstrations against war, brutally repressed by the police. On 27th July, the CGT called a demonstration, and “from 9 o'clock to midnight (…) an enormous crowd flowed without a break along the Boulevards. Huge numbers of police were mobilised (…) But the workers who came to the city centre from the outskirts were so numerous that the police tactics [of splitting up the workers] led to an unexpected result: there were soon as many demonstrations as there were streets. Police violence and brutality failed to dampen the crowds' combativeness; throughout the evening, the cry of 'Down with war' resounded from Opéra to the Place de la République”.40 The demonstrations continued the following day, and spread to the major towns in the provinces.

The French bourgeoisie was faced with another problem: the attitude of the socialist leader Jean Jaurès. Jaurès was a reformist, at a moment in history when reformism became an untenable middle ground between bourgeoisie and proletariat, but he was profoundly attached to the defense of the working-class (and his reputation and influence among the workers was for this reason very great), and passionately opposed to war. On 25th July, when Serbia's rejection of the Austro-Hungarian ultimatum was reported in the press, Jaurès was due to speak at an electoral meeting in Vaise, near Lyon: his speech was devoted not to the election, but to the terrible danger of war. “Never in forty years has Europe been confronted with a more threatening and tragic situation (…) A terrible danger menaces peace, and the lives of men, against which the proletarians of Europe must make the supreme effort of solidarity of which they are capable”.41

At first, Jaurès believed the French government's fraudulent assurances that it was working for peace, but by the 31st July he was disillusioned and in Parliament was once again calling on the workers to resist war to the utmost. Rosmer takes up the story: “the rumour spread that the article he was shortly to write for the Saturday issue of L'Humanité would be a new 'J'accuse!'42 denouncing the intrigues and lies that had brought the world to the brink of war. In the evening, (…) he led a delegation of the Socialist [parliamentary] group to the Quai d'Orsay43. [Foreign Minister] Viviani was absent, and the delegation was received by under-secretary of state Abel Ferry. After hearing Jaurès out, he asked what the socialists intended to do in the situation. 'Continue our campaign against the war' replied Jaurès. To which Ferry answered: 'That you will never dare, for you will be killed on the next street corner'.44 Two hours later, Jaurès was about to return to his office at L'Humanité to write the dreaded article, when he was shot down by the assassin Raoul Villain; two revolver shots at point-blank range caused his instant death”.45

Decidedly, the French ruling class was leaving nothing to chance in order to ensure “unity and national cohesion”!

No war without workers

So when the wreaths are laid, when the great and the good bow their heads in sorrow during the commemorations that our rulers are buying at the cost of millions of pounds or euros, when the trumpets sound the last call at the end of these solemn ceremonies, when the documentaries unfold on the TV screens and the learned historians discourse on all the reasons for war except the one that really matters, and on all the factors that might have prevented the war except the one that could really have weighed in the balance, then let the proletarians of the world remember.

Let them remember that World War I was caused not by historical happenstance, but by the inexorable workings of capitalism and imperialism, that the world war opened a new period in history, an “epoch of wars and revolutions” as the Communist International called it. This period is still with us today, and the same forces that drove the world to war in 1914 are responsible today for the endless massacres in the Middle East and Africa, for the ever more dangerous tensions between China and its neighbours in the South China Sea.

Let them remember that wars cannot be fought without workers, as cannon fodder and to man the factories. Let them remember that the ruling class must have national unity for war, and that they will stop at nothing to get it, from police repression to bloody assassination.

Let them remember that it is those very same “Socialist” parties that today stand to the forefront of every pacifist campaign and humanitarian protest, who betrayed their forebears' trust in 1914, leaving them unorganised and defenceless to face capitalism's machinery of war.

And finally, let them remember that, if the ruling class had to make such an effort to neutralise the working class in 1914 it is because only the world proletariat can stand as an effective barrier to imperialist war. Only the world proletariat bears within itself the hope of overthrowing capitalism, and the danger of war, once and for all.

One hundred years ago, humanity stood before a dilemma whose solution lies in the hands of the proletariat alone: socialism or barbarism. That dilemma is still with us today.

Jens

1Ironically perhaps, the film's title was taken from a pre-war book by British economist Norman Angell, which argued that war between the developed capitalist powers had become impossible because their economies were too closely integrated and interdependent – precisely the same kind of argument that we hear today in relation to China and the United States.

2Needless to say, like all the other works we have mentioned, All quiet on the Western Front was banned by the Nazis after 1933. It was also banned from 1930 to 1941 by the Australian film censorship.

3In striking contrast, Britain's best-known patriotic war poet Rupert Brooke never actually saw combat, falling sick and dying en route for the assault on Gallipoli.

4 This has been the object of some polemic in the German press.

5A worthy project in its own right, no doubt, but not one that will contribute much to an understanding of why war broke out.

7 “Commémorer la Grande Guerre (2014-2020) : propositions pour un centenaire international” by Joseph Zimet of the “Direction de la mémoire, du patrimoine et des archives”.

8It is striking that the great majority of executions for military disobedience in the French army took place during the first months of war, which suggests a lack of enthusiasm which had to be crushed from the outset. See the report presented to the Minister for War Veterans Kader Arif in October 2013: https://centenaire.org/sites/default/files/references-files/rapport_fusi... [4]

9It is worth mentioning here that the title The Sleepwalkers is taken from Hermann Broch’s trilogy of the same name, written in 1932. Broch was born 1886 in Vienna to a Jewish family, but converted in 1909 to Roman Catholicism. In 1938, after the annexation of Austria, he was arrested by the Gestapo. However, with the help of friends (including James Joyce, Albert Einstein and Thomas Mann) he was allowed to emigrate to the US where he lived until his death in 1951. Die Schlafwandler is the story of three individuals from 1888, 1905 and 1918 respectively, and examines the questions of the decomposition of values and subordination of morality to the laws of profit.

10Confédération Générale du Travail. See "Anarcho-syndicalism faces a change in epoch: the CGT up to 1914 [5]", in International Review n°120.

11 See Hew Strachan, The First World War, volume 1

12 See The Junius Pamphlet [6] on marxists.org

13 Editions d'Avron, May 1993.

14 The second volume was published after World War II and is much shorter, since Rosmer had to flee Paris during the Nazi occupation, and his archives were seized and destroyed during the war.

15 Rosmer, p84

16 Junius, Chapter 6

17Luxemburg quotes here a letter from Marx to the Braunschweiger Ausschuss: “He who is not deafened by the momentary clamour, and is not interested in deafening the German people, must see that the war of 1870 carries with it, of necessity, a war between Germany and Russia, just as the war of 1866 bore the war of 1870. 1 say of necessity, unless the unlikely should happen, unless a revolution breaks out in Russia before that time If this does not occur, a war between Germany and Russia may even now be regarded as un fait accompli. It depends entirely upon the attitude of the German victor to determine whether this war has been useful or dangerous. If they take Alsace-Lorraine, then France with Russia will arm against Germany. It is superfluous to point out the disastrous consequences”.

18 Junius, Chapter 3 [7]

19Idem.

20The first Moroccan crisis in 1905 was provoked by the Kaiser's visit to Tangier, supposedly to support Moroccan sovereignty but in reality in an attempt to counter French influence in the country. Military tension was extreme: the French cancelled all military leave and advanced troops to the border with Germany, while Germany began to call up reservists. In the end the French backed down and accepted the German proposal of a multi-national conference, held in Algeciras in 1906. Here, the Germans had a shock when they found themselves abandoned by all the participating European powers, especially the British, and could only get the support of Austria-Hungary. The second Moroccan crisis came in 1911 when a rebellion against the Sultan Abdelhafid gave France the pretext for dispatching troops to the country under the pretext of protecting European citizens. The Germans seized on the same pretext to send the gunboat Panther to the Atlantic port of Agadir. This the British saw as a prelude to the installation of a German naval facility on the Atlantic coast directly threatening Gibraltar. Lloyd George's Mansion House speech (cited by Rosmer) was a barely veiled declaration that Britain would go to war if Germany did not back down. In the end, Germany recognised the French “protectorate” in Morocco, in exchange for some swampland at the mouth of the Congo.

21The Germans established the brewery which now produces “Tsingtao” beer.

22The idea put forward by Clark, but also by Niall Ferguson in The Pity of War, that Germany remained far behind Britain in the naval arms race, is absurd: Britain's navy, unlike Germany's, had to protect worldwide shipping, and it is hard to see how Britain could not feel threatened by the construction of at least a major naval force less than 500 miles from its capital city and closer still to its coast.

23Although, in European texts of the period, Turkey is used interchangeably with the term “Ottoman Empire”, it is important to remember that the latter is more accurate: at the beginning of the 19th century, the Ottoman Empire covered not only Turkey but also present-day Libya, Syria, Iraq, the Arabian peninsula, a large part of Greece and the Balkans.

24This refinery was important above all for military reasons: Britain's fleet had been converted from coal-fired to oil-fired engines, and while Britain had coal in abundance it had no oil. The search for oil in Persia was prompted above all by the Royal Navy's need to secure a constant oil supply for the fleet.

25Junius, Chapter 4

26The First Balkan War broke out in 1912, when the members of the Balkan League (Serbia, Bulgaria and Montenegro), with the tacit support of Russia, attacked the Ottoman Empire. Although not part of the Balkan League, Greece also joined in the fighting, at the end of which the Ottoman armies had been largely defeated: the Ottoman Empire lost most of its European territory for the first time in 500 years. The Second Balkan War broke out immediately afterwards, in 1913, when Bulgaria attacked Serbia which had occupied, in connivance with Greece, a large part of Macedonia that it had originally promised to Bulgaria.

27Junius

29These documents were seized by the Germans, who published substantial extracts after the war. As Rosmer points out, “The evaluations by Belgium's representatives in Berlin, Paris and London have a special value. Belgium is neutral, and they can thus be more open-minded in evaluating events; moreover they are well aware that should war break out between the two great opposing blocs, their little country will find itself in serious danger, in particular of serving as a battle-field” (ibid, p68).

30Ibid, p69.

31Ibid, p70.

32Ibid, p71.

33Ibid, p73.

34Ibid, p72.

35Rosmer, p87.

36Indeed, the government had already attempted to bring pressure to bear by leaking fake documents purporting to reveal a Serbian plot against Bosnia-Herzegovina to the historian Heinrich Friedjung (cf Clark, loc 1890).

37Quoted by Rosmer, p87, from German documents published after the war.

38Rosmer, p87.

40Rosmer, p102.

41Ibid, p84.

42A reference to Emile Zola's devastating attack on the government during the Dreyfus affair

43The Foreign Ministry

44Rosmer, p91. The conversation is reported in Charles Rappoport's biography of Jaurès, and confirmed in Abel Ferry's own papers. Cf Alexandre Croix, Jaurès et ses détracteurs, Editions Spartacus, p313.

45Jaurès was shot while eating at the Café du Croissant, opposite the offices of L'Humanité. Raoul Villain was in some ways similar to Gavrilo Princip: unstable, emotionally fragile, given to political or religious mysticism – in short, precisely the kind of character that the secret services use as expendable provocateurs. After the murder, Villain was arrested and spent the war in the security, if not the comfort, of prison. At his trial, he was acquitted and Jaurès' widow was ordered to pay costs.

Historic events:

- World War I [1]

- Ottoman Empire [10]

- Tsingtao [11]

- Balkan Wars [12]

- Fashoda Incident [13]

- Moroccan Crisis [14]

- Baghdad Railway [15]

General and theoretical questions:

- War [16]

People:

- Rosa Luxemburg [17]

- Bismarck [18]

- Gavrilo Princip [19]

- Wilfred Owen [20]

- Jaroslav Hasek [21]

- Albert Südekum [22]

- Raymond Poincaré [23]

- Alfred Rosmer [24]

- von Bülow [25]

- Bethmann-Hollweg [26]

- Jean Jaurès [27]

- Abel Ferry [28]

- Viviani [29]

Recent and ongoing:

- Christopher Clark [30]

Rubric:

1914: how German socialism came to betray the workers

- 5379 reads

Of all the parties federated in the 2nd International, the Sozialdemokratische Partei Deutschlands (SPD) was by far the most powerful. In 1914, the SPD had more than one million members, and had won more than four million votes in the 1912 parliamentary elections:1 it was, in fact, the only mass party in Germany and the biggest single party in the Reichstag – although under the autocratic imperial regime of Kaiser Wilhelm II it had no chance of actually forming a government.

For the other parties of the 2nd International, the SPD was the party of reference. Karl Kautsky,2 editor of the Party's theoretical journal Neue Zeit, was the acknowledged "pope of marxism", the International's leading theoretician; at the 1900 Congress of the International, Kautsky had drawn up the resolution condemning the participation of the French socialist Millerand in a bourgeois government, and the SPD's Dresden Congress of 1903, under the leadership of its chairman August Bebel,3 had roundly condemned the revisionist theories of Eduard Bernstein and reasserted the SPD's revolutionary goals; Lenin had praised the SPD's "party spirit" and its immunity to the petty personal animosities that had led the Mensheviks to split the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP) after its 1903 congress.4 To cap it all, the SPD's theoretical and organisational supremacy was clearly crowned by success on the ground: no other party of the International could claim anything close to the SPD's electoral success, and when it came to trade union organisation only the British could rival the Germans in the numbers and discipline of their members.

“In the Second International the German ‘decisive force’ played the determining role. At the [international] congresses, in the meetings of the international socialist bureaux, all awaited the opinion of the Germans. Especially in the questions of the struggle against militarism and war, German Social Democracy always took the lead. ‘For us Germans that is unacceptable’ regularly sufficed to decide the orientation of the Second International, which blindly bestowed its confidence upon the admired leadership of the mighty German Social Democracy: the pride of every socialist and the terror of the ruling classes everywhere”.5

It was obvious therefore, as the storm clouds of war began to gather in the month of July 1914, that the attitude of the German Social Democracy would be critical in deciding the outcome. The German workers – the great masses organised in the Party and the unions, which the workers had fought so hard to build – were placed in a position where they alone could tip the scales: towards resistance, the fighting defence of proletarian internationalism, or towards class collaboration and betrayal, and years of the bloodiest slaughter humanity had ever witnessed.

“And what did we in Germany experience when the great historical test came? The most precipitous fall, the most violent collapse. Nowhere has the organization of the proletariat been yoked so completely to the service of imperialism. Nowhere is the state of siege borne so docilely. Nowhere is the press so hobbled, public opinion so stifled, the economic and political class struggle of the working class so totally surrendered as in Germany.”6

The betrayal of German Social Democracy came as such a shock to revolutionaries that when Lenin read in Vorwärts7 that the SPD parliamentary fraction had voted in favour of war credits, he at first took the issue for a fake, black propaganda put out by the Imperial government. How was such a disaster possible? How, in a matter of days, could the proud and powerful SPD renege on its most solemn promises, transforming itself overnight from the jewel in the crown of the workers’ International to the most powerful weapon in the armoury of the war-mongering ruling class?

As we try, in this article, to answer this question, it might seem paradoxical to concentrate in large part on the writings and actions of a relatively small number of individuals: the SPD and the unions were after all mass organisations, capable of mobilising hundreds of thousands of workers. It is justified however, because individuals like Karl Kautsky or Rosa Luxemburg represented, and were seen at the time to represent, definite tendencies within the Party; in this sense, their writings gave voice to political tendencies with which masses of militants and workers – who remain anonymous to history – identified. It is also necessary to take account of these leading figures’ political biographies if we are to understand the weight they had in the Party. August Bebel, chairman of the SPD from 1892 until his death in 1913, was one of the Party's founders and had been imprisoned, along with his fellow Reichstag deputy Wilhelm Liebknecht, for their refusal to support Prussia's war against France in 1870. Kautsky and Bernstein had both been forced into exile in London by Bismarck's anti-socialist laws, where they had worked under Engels’ direction. The prestige, and the moral authority, that this gave them in the Party was immense. Even Georg von Vollmar, one of the leaders of South German reformism, first came to prominence as a left-winger and a vigorous and talented underground organiser, suffering repeated prison sentences as a result.

This then was a generation which had come to political activity through the years of the Franco-Prussian war and the Paris Commune, through the years of clandestine propaganda and agitation in the teeth of Bismarck's anti-socialist laws (1878-1890). Of a very different stamp were men like Gustav Noske, Friedrich Ebert, or Philipp Scheidemann, all members of the right wing in the parliamentary fraction of the SPD who voted for war credits in 1914 and played a key role in the suppression of the 1919 German Revolution – and in the murder of Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Liebknecht by the Freikorps. Rather like Stalin, these were men of the machine, working behind the scenes rather than actively participating in public debate, the representatives of a Party which, as it grew, tended more and more to resemble and identify with the German state whose downfall was still its official goal.

The revolutionary left ranged against the growing tendency within the Party to make concessions to "practical politics" and was, strikingly, in large part both foreign and young (one notable exception being the old Franz Mehring). Apart from the Dutchman Anton Pannekoek, and Wilhelm Liebknecht's son Karl, men like Parvus, Radek, Jogiches, Marchlewski, all came from the Russian empire and were forged as militants under the harsh conditions of Tsarist oppression. And of course, the outstanding figure on the left was Rosa Luxemburg, an outsider in the German Party in every possible way: young, female, Polish, and Jewish, and – perhaps worst of all from the point of view of some of the German leadership – standing intellectually and theoretically head and shoulders above the rest of the Party.

The foundation of the SPD

The Sozialistische Arbeiterpartei (SAP – German Workers’ Party), later to become the SPD, was founded in 1875 in Gotha, by the merger of two socialist parties: the Sozialdemokratische Arbeiterpartei (SDAP),8 led by Wilhelm Liebknecht and August Bebel, and the Allgemeiner Deutscher Arbeiterverein (ADAV), originally established by Ferdinand Lassalle in 1863.

The new organisation thus sprang from two very different sources. The SDAP had only been in existence for six years; through Marx and Engels’ longstanding relationship with Liebknecht – although Liebknecht was no theoretician he played an important role in introducing men like Bebel and Kautsky to Marx's ideas – they had played an important part in the SDAP's development. In 1870, the SDAP adopted a resolutely internationalist line against Prussia's war of aggression on France: at Chemnitz, a meeting of delegates, representing 50,000 Saxon workmen, adopted unanimously a resolution to this effect: “In the name of German Democracy, and especially of the workmen forming the Democratic Socialist Party, we declare the present war to be exclusively dynastic... We are happy to grasp the fraternal hand stretched out to us by the workmen of France... Mindful of the watchword of the International Working Men’s Association: Proletarians of all countries, unite, we shall never forget that the workmen of all countries are our friends and the despots of all countries our enemies.”.9

The ADAV, by contrast, had remained faithful to its founder Lassalle's opposition to strike action, and his belief that the workers' cause could be advanced by an alliance with the Bismarckian state, and more generally through the recipes of “state socialism”.10 During the Franco-Prussian war, the ADAV remained pro-German, its then President, Mende, even pushing for French war reparations to be used to set up state workshops for German workers.11

Marx and Engels were deeply critical of the merger, although Marx's marginal notes on the programme was not made public until much later,12 Marx considering that “Every step of real movement is more important than a dozen programmes”.13 Although they refrained from open criticism of the new Party, they made their views clear to its leading members, and in writing to Bebel, Engels highlighted two weaknesses which, untreated, were to sow the seeds of the 1914 betrayal:

-

“the principle that the workers’ movement is an international one is, to all intents and purposes, utterly denied in respect of the present, and this by men who, for the space of five years and under the most difficult conditions, upheld that principle in the most laudable manner. The German workers’ position in the van of the European movement rests essentially on their genuinely international attitude during the war; no other proletariat would have behaved so well. And now this principle is to be denied by them at a moment when, everywhere abroad, workers are stressing it all the more by reason of the efforts made by governments to suppress every attempt at its practical application in an organisation! (...)

-

as its one and only social demand, the programme puts forward — Lassallean state aid in its starkest form, as stolen by Lassalle from Buchez. And this, after Bracke has so ably demonstrated the sheer futility of that demand; after almost all if not all, of our party speakers have, in their struggle against the Lassalleans, been compelled to make a stand against this “state aid"! Our party could hardly demean itself further. Internationalism sunk to the level of Amand Goegg, socialism to that of the bourgeois republican Buchez, who confronted the socialists with this demand in order to supplant them!”14

These fault-lines in practical politics were hardly surprising given the new Party's eclectic theoretical underpinnings. When Kautsky founded the Neue Zeit in 1883, he intended it to be “published as a Marxist organ which had set itself the task of raising the low level of theory in German social democracy, destroying eclectic socialism, and achieving victory for the Marxist programme”; he wrote to Engels: “I may be successful in my attempts to make the Neue Zeit the rallying point of the Marxist school. I am winning the collaboration of many Marxist forces, as I am getting rid of eclecticism and Rodbertussianism”.15

From the outset, including during its underground existence, the SAP was thus a battleground of conflicting theoretical tendencies – as is normal in any healthy proletarian organisation. But as Lenin once remarked “Without revolutionary theory, no revolutionary practice”, and these different tendencies, or visions, of the organisation and of society, were to have very practical consequences.