Imperialism in Asia in the 21st century

- 2543 reads

Rubric:

Imperialism in Asia in the 21st century - Introduction

- 1584 reads

During the first half of 2012 several successful or failed long-distance missile tests by Korea (North and South), China, India and Pakistan have turned a spotlight on the ambitions of all the bigger Asian countries. At the same time gigantic orders of warships have highlighted the ongoing militarisation of the blue waters1 across all Asia. In fact, all the Asian countries have been forced to position themselves in relation to the newly emerging powers China and India. Their ambitions and the US strategy of creating a counter-weight to China have unleashed an arms race engulfing all Asia.

While commentary in the press has until recently concentrated mainly on their double-digit growth figures, the economic rise of the two Asian powers has inevitably been accompanied by a rise in their imperialist ambitions. To understand this situation, we first need to place it within a broader historical context.

While commentary in the press has until recently concentrated mainly on their double-digit growth figures, the economic rise of the two Asian powers has inevitably been accompanied by a rise in their imperialist ambitions. To understand this situation, we first need to place it within a broader historical context.

Asia's overall weight in world production is returning to the historical norm prior to the rise of European capitalism. Between the 11-17th century China commanded the world's biggest fleet. Until the 18th century, China led Europe technically. In 1750 China's share of world manufacturing was almost one third, whereas Europe's still stood at only one quarter. But with the 19th century expansion of capitalist powers into China and India, both countries2 were overshadowed and their relative share of world production declined.

Today, China is recovering its original position as one of the world's major centres of production and power. But can its return to centre-stage be "peaceful" and "harmonious" as its leadership claims?

All the Far Eastern countries3 rely heavily on sea lanes which run through three bottle-necks: the South China Sea (SCS), the Strait of Malacca (between Malaysia, Singapore, and Indonesia) and the Strait of Hormus (between Iran and Dubai). “More than half of the world's annual merchant fleet tonnage passes through the Straits of Malacca, Sunda, and Lombok, (Indonesia) with the majority continuing on into the South China Sea. Tanker traffic through the Strait of Malacca leading into the South China Sea is more than three times greater than Suez Canal traffic, and well over five times more than the Panama Canal. Virtually all shipping that passes through the Malacca and Sunda Straits must pass near the Spratly Islands”.4

90% of Japan's imported oil passes through the South China Sea. Almost 80% of China’s oil passes through the Strait of Malacca. At the moment the largely USA dominates these bottlenecks. As an emerging power China finds this situation unbearable – because their control by a single power like the USA could strangle China.

Although the 20th century's first major imperialist conflict took place between two Asian powers (the Russo-Japanese war of 1905), the main battles of World War I took place in Europe and the battle fields in Asia remained marginal, World War II, however, involved Asia far more deeply in the general destruction. Some of the fiercest and bloodiest battles took place in Asia. After World War II, while the European continent was divided by the “Iron Curtain”, stretching across Central Europe through divided Germany, four Asian countries were divided in two: Korea, China, Vietnam (since reunited) and India. Whereas in Europe the Iron Curtain came down in 1989, the divisions in Asia continue to exist, each of them creating permanent conflicts and some of the world's most militarised border zones (North / South Korea, Peoples' Republic of China / Taiwan, Pakistan / India). But now it is not only the conflicts between the divided countries which continue to fuel imperialist tensions, it is above all the rise of a new challenger, China, and the reactions by the neighbouring countries and the challenged super-power, the USA, which aggravate the tensions.

1 This refers to the notion of a "blue-water navy", a rather imprecise term which generally indicates a navy capable of projecting power in international waters outside its own coastal waters.

2 India of course was not a country in the 19th century. Indeed India as a single political unit cannot be said to have existed until the British Raj.

3 The term "Far East" is of course entirely Euro-centric. For the USA, the region is the "Far West", while for Asian countries themselves the region is obviously central. We therefore use the term purely as a matter of convention and literary convenience.

4 cf. https://www.globalsecurity.org/military/world/war/spratly-ship.htm [1] and https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Shipping_routes_red_black.png [2])

Asia 1945-1989

- 2111 reads

While the confrontation between the Russian bloc countries and the US bloc was at the centre of the Cold War after 1945, China has the specificity of having clashed simultaneously with the two bloc leaders of the time, the USA and Russia. Thus the imperialist rivalries in the East have never been limited to conflicts between the two blocs: ever since its liberation from Japanese colonialism China has shown a tendency to try to “go it alone”. When the East-West confrontation ended in 1989, the seeds of a new confrontation between China and the USA, which had been retarded by the situation of the Cold War between 1972-1989, were to germinate. In the context of a general disorder on the imperialist stage, China's economic emergence necessarily set the clock ticking for new military confrontations with the USA.

The imperialist development in Asia has been marked by the specificity of India and China.

China entered the post-war period devastated by militarism: repeated intervention by Western imperialism during the 19th century, the collapse of central state power and the rise of warlordism, Japanese invasion and more than ten years of bitter and barbaric warfare, then civil war between the Kuomingtang and the Red Army, until the Communist Party of China (CPC) seized power in 1949. All this left the country in a state of extreme economic backwardness (made even more catastrophic by the attempt to catch up with the developed world during the "Great Leap Forward") and militarily weak, dependent on the sheer weight of numbers of a poorly armed peasant army. In the case of India, whose economy was equally backward in relation to foreign competitors due to the long weight of colonialism, the new ruling faction which took over power after independence in 1947 aggravated this condition with its semi-isolationist policy. Both India and China cut themselves off in different degrees from the world market. Thus Stalinism in the specific form of Maoism in China, semi-isolation in the specific form of Ghandism in India were historic chains which meant the two rivals started their emergence from a low initial level of development. The determination of the Chinese ruling class to adapt its forces substantially and with a long-term view to challenging the USA is thus all the more striking.

Since 1989 a change has been unfolding in Asia's imperialist hierarchy: overall, China and India have been on the rise, Japan has been on a relative decline, while Russia, after almost disappearing from the world scene after the implosion of the USSR, is making something of a comeback. The position of the only remaining superpower, the USA, has been weakened – not only in Asia but throughout the world. The USA is now struggling to maintain its superiority in Asia.

The situation in Asia is dominated by a complex web of shifting alliances and counter-alliances. Each state is trying to fend off the ambitions of its rivals, while all of them want to restrain China's dominance without becoming mere puppets of the only power able to confront China: the USA. This web of alliances can be seen all along the different zones of conflict from North Korea via Taiwan, the South China Sea, the Strait of Malacca, the Indian Ocean, to the Persian Gulf and the Middle East.

China's imperialist ambitions in continuity with decades of militarism

- 2170 reads

The People’s Republic of China (PRC) was founded on the basis of the partition between the PRC and Taiwan – each with their supporting bloc (the USA and Russia). The history of the PRC since its foundation has been marked by a series of military conflicts with its neighbours:

1952: China was heavily involved in the Korean War. This was the first big clash between the USA and the Soviet Union and China on the Korean peninsula.

1950-1951 Chinese troops occupied Tibet. Between 1956-59 there was prolonged fighting between the Chinese army and Tibetan guerrillas.

1958: China bombarded Taiwan's Quemoy and Matsu islands.

1962: China was involved in a border dispute with India in the Himalayas. Since then China has been a staunch defender of Pakistan in its stand-off with India.

1963-64: After having been allies for more than a dozen years China and the Soviet Union split. While the Soviet Union was engaged in an arms race with the US bloc, an additional confrontation arose between China and the Soviet Union. In March 1969 a serious clash occurred at the Ussuri River with dozens of Russian soldiers killed or wounded. By 1972, 44 Soviet divisions were stationed along the 7000km border with China (Russia had “only” 31 stationed in Europe). One quarter of Soviet aviation was transferred to its eastern border. In 1964 the USA envisaged the possibility of a nuclear attack - together with Russia - against China. And in 1969 the Russians still had plans to launch nuclear missiles against China.1 The conflict between the USA and China ebbed in the early 1970s. After a long and bloody war trying to prevent South Vietnam from falling into Russian hands, in 1972 the USA succeeded in “neutralising” China, while the confrontation between China and Russia continued and took the form of proxy wars. Thus between 1975-1979, soon after the end of war in Vietnam, a first proxy war broke out between Vietnam (supported by Russia) and Cambodia (supported by China); others followed, particularly in Africa.

1979: China fared disastrously in a 16-day war with Vietnam, where both sides mobilized between them more than one million soldiers and left tens of thousands of victims behind. The Chinese army's weaknesses were made glaringly obvious. In 1993 it abandoned the “people’s war” or “war of attrition” tactics, based on the sacrifice of an unlimited number of soldiers. The adaptation to war under high-tech conditions was initiated after this experience.

When the Soviet Union invaded Afghanistan in December 1979 the PRC entered a tri-partite alliance with the U.S. and Pakistan, to sponsor Islamist Afghan armed resistance to the Soviet Occupation (1979–89). China acquired military equipment from America to defend itself from Soviet attack. The Chinese People's Liberation Army trained and supported the Afghan Mujahidin during the Soviet o2.

Thus during the first four decades of its existence, the People’s Republic of China was involved in armed conflict with almost all of its neighbors: the Soviet Union, Korea and the USA, Japan, Taiwan, Vietnam, India. And for many years during the Cold War, China clashed with both bloc leaders simultaneously. Of the fourteen separate nation states that border China, ten still have outstanding frontier disputes with it. Thus the present sharpening of tensions in particular with the USA is not new, it is in continuity with decades of conflict. That said, in recet years a new polarisation around China has emerged.

While for decades the PRC had its troops massed at the Russian border, concentrated its forces for protecting its coast line and maintained readiness to wage war with Taiwan, in the early 1990s the PRC systematically started to adapt to the new world situation created by the collapse of the USSR.

China takes to the seas

- 1501 reads

Beijing policy during the past 20 years has aimed at:

1) Developing a long-term strategy to operate in blue-water seas, combined with efforts to acquire or develop its weapons for cyberspace and space, and to enhance its aviation's range and striking power. The long-term aim is to prevent the USA from being the dominant force in the Pacific - the military call this “anti-access/area denial” capabilities. The idea is to use pinpoint ground attack and anti-ship missiles, a growing fleet of modern submarines, cyber and anti-satellite weapons to destroy or disable another nation’s military assets from afar. This marks a shift away from devoting the bulk of the PLA's modernisation drive to the goal of capturing Taiwan. Whereas historically the goal of recapturing Taiwan and acting as a coastal force defending its coast line with a certain “continental” outlook was the main strategic orientation, China now aims to advance into blue-water. This more assertive posture was influenced by the 1995-96 Taiwan Straits crisis that saw two US carriers humiliate Beijing in its home waters. China is investing heavily in “asymmetric capabilities” designed to blunt America’s once-overwhelming capacity to project power in the region. Thus China aims to be able to launch disabling attacks on American bases in the western Pacific and push America’s carrier groups beyond what it calls the “first island chain”, sealing off the Yellow Sea, South China Sea and East China Sea inside an arc running from the Aleutians in the north to Borneo in the south. In the western Pacific, that would mean targeting or putting in jeopardy America’s aircraft-carrier groups and its air-force bases in Okinawa, South Korea and even Guam. Since World War II, America's allies in the Asia-Pacific region have counted on the U.S. to provide a security umbrella. But now "The assumption that U.S. and allied naval surface vessels can operate with high security in all parts of the Western Pacific is no longer valid" a US report has said. U.S. aircraft carrier strike groups, it said, are becoming "increasingly vulnerable" to Chinese surveillance and weaponry up to 1,200 nautical miles from China's coast1.

2) At the same time China wants to have a presence at various maritime bottle-necks, which means expanding into the South China Sea and the Indian Ocean. Unable to snatch territories from its neighbours in the north, east and west, it must focus its forces on imposing its presence in the South China Sea, the Indian Ocean (far sea defence) and towards the Middle East. This means above all it must undermine the still dominant US position in the blue waters. While claiming a dominant position in the South China Sea, it has started to set up a “string of pearls” around India and is stretching out its fingers towards the Middle East.

A deadly “string of pearls”

- 2732 reads

In addition to the long-standing close links with the regimes in Pakistan and Burma, China has been following a “string of pearls” strategy of setting up bases and building diplomatic ties. Some examples:

-

Signature of a military agreement with Cambodia.

-

Funding the construction of a canal across the Kra Isthmus in Thailand. The canal is planned to be 102 kilometres long and 500 metres wide and is to link the Indian Ocean to China’s Pacific coast – a project on the scale of the Panama Canal. It could tip Asia’s balance of power in China’s favour by giving China’s fleet and merchant navy easy access to a vast oceanic continuum stretching all the way from East Africa to Japan and the Korean Peninsula. This proposed canal would challenge Singapore’s position as the main regional port and help Chinese vessels to avoid the straits of Malacca. This has great strategic significance for the naval balance of power, and challenges India’s present dominant position in the Bay of Bengal1.

-

Construction of strategic infrastructure in Tibet and Myanmar.

-

Developing a port facility in Sittwe, Myanmar.

-

Electronic intelligence gathering facilities on islands in the Bay of Bengal.

-

Assistance to Bangladesh in developing its deep-sea port in Chittagong, sales of missile boats to Bangladesh.

-

Extensive military aid to Sri Lanka. China helped Sri Lanka to win the war against the Tamil Tigers in 2009, it also invested in the development of ports in Hambantota.

-

Building a naval base at Marao in the Maldives.

-

Setting up its first military base abroad in Seychelles.

-

Developing the Gwadar port on the south-west coast of Pakistan. China’s involvement in the construction of the deep-sea port of Gwadar has attracted much attention given its strategic location, about 70 kilometres from the Iranian border and 400 kilometres east of the Strait of Hormuz - the world's major oil supply route. It has been suggested that it will provide China with a “listening post” from where it can monitor US naval activity in the Persian Gulf and Indian activity in the Arabian Sea.

-

An anti-piracy mission in the Gulf of Aden.

The construction of such a “string of pearls” would allow China to threaten shipping at the three crucial bottlenecks in the Indian Ocean – Bab el Mandeb (connecting the Red Sea to the Gulf of Aden), the Strait of Hormuz, and the Strait of Malacca. Chinese naval officers speak of developing in the long-term three ocean-going fleets to patrol the seas around Japan and Korea, the Western Pacific, the Strait of Malacca and the Indian Ocean.

The construction of such a “string of pearls” would allow China to threaten shipping at the three crucial bottlenecks in the Indian Ocean – Bab el Mandeb (connecting the Red Sea to the Gulf of Aden), the Strait of Hormuz, and the Strait of Malacca. Chinese naval officers speak of developing in the long-term three ocean-going fleets to patrol the seas around Japan and Korea, the Western Pacific, the Strait of Malacca and the Indian Ocean.

As an emerging power, China claims more weight and influence, but this can only be at the expense of other countries, in particular at the expense of the USA. This polarises the whole regional situation. Countries are drawn towards China, or into the arms of the USA, whether they like it or not.

The Chinese ruling class want to make us believe that Beijing’s rise is meant to be a peaceful one, and that China has no expansionist intentions, that it will be a different kind of great power. The reality of the past 20 years shows that China's rise is inseparable from increased imperial and military ambitions. While it is unthinkable that China could today defeat the USA or set up a new Chinese-led bloc, the main impact of China’s rise has been to undermine US superiority: its ambitions have triggered a new arms race. In addition, its increased weight world wide has encouraged the weakened former bloc leader, Russia, to act side-by-side with China in many conflicts with the USA (e.g. Syria, Iran) and to support (overtly or covertly) all those regimes which are denounced by the USA as “rogue states" (North Korea, Iran) or which are “failed states” such as Pakistan. Although Russia is also not interested in seeing China becoming too strong, and while Moscow has no intention of becoming a servant of China, Russia has realised that acting together with China against the USA offers it greater new room for manoeuvre. This explains Russia's naval exercises with China in the Yellow Sea.

The arms race between China and its rivals

Since 1989, the Chinese military budget has risen by an average of 12.9 percent per year: according to GlobalSecurity.org, it is now the second-largest on the planet. The overall US budget for national security – not counting the various wars Washington is embroiled in – is running at over $800 billion, although some estimates place it above $1 trillion. Global research group IHS has forecast Beijing's military outlay to double from its 2011 US$119.8 billion, to US$238.2 billion by 2015. That exceeds the amount spent by the region's 12 key defense markets, including Japan and India. In 2011 Chinese military spending was 80% higher than that of Japan, and 200% higher than those of India. China's military budget in 2011 was 2.5 times bigger than the 2001 figure and has doubled every five years. China's military budget takes up 30% of the Asian total, although according to Western defense officials those totals do not include arms imports. Thus in reality the overall military budget is much higher. If the forecast is accurate, China’s military spending will overtake the combined military spending of NATO’s top eight members, bar the US. And while in the year 2000 the US military budget was still 20 times higher than the Chinese, in 2011/2012 the relation is 7:1.2

China's modernisation efforts have been directed mainly at developing longer range missiles and increasing its cyber-war capabilities. Its navy is now believed to be the third largest in the world behind only the US and Russia. The PLA's infantry contingent has been reduced, while the navy, air force and the Second Artillery Corps – responsible for China’s nuclear missiles – have all been increased.

While Chinese growth rates have often reached double figures, its military budget has grown even faster. To be sure, the Chinese army started from a weak position of, since the majority of its forces were land forces, poorly equipped and mainly seen as cannon fodder for big land battles. The Chinese military has little fighting experience. Their troops have not seen action since 1979 when they were given a drubbing by Vietnam. In contrast US troops have been fighting, modernising, and adapting their weaponry and tactics constantly, developing anti-satellite weapons, anti-ship missiles, cruise missiles, and cyber-warfare capabilities. The PLA's ability to undertake complex joint operations in a hostile environment is untested. China’s missile and submarine forces could pose a threat to American carrier groups near its coast, but it will be some time until they can do so further afield. Learning to use all these newly acquired weapons in battle il likely to take years. Nevertheless, these ambitious armaments projects and China's expansionist strategy mean that the USA now perceives it among "major and emerging powers” as the country with “greatest potential to compete militarily” with the United States. Although even according to the Pentagon the Chinese military is "still decades away from possessing a comprehensive capability to engage and defeat a modern adversary beyond China's boundaries", leaders in the USA warn that “China's military is growing and modernizing." "We must be vigilant. We must be strong. We must be prepared to confront any challenge. But the key to that region is going to be to develop a new era of defense cooperation between our countries, one in which our military shares security burdens in order to advance peace." (the 2012 US defence secretary Panetta3).

As a consequence of the construction of the “string of pearls” and the growing Chinese presence in the Pacific, its neighbours have been compelled to adapt their military planning. Some examples:

Japan has switched from having its weapons targeted principally at the Soviet Union to focus more on China. Despite the effects of the economic crisis Japan plans to spend $284 billion between 2011 and 2015 – including the deployment of more US Patriot missiles; the navy is to receive more blue-water ships. Japan and China are currently engaged in a dispute over a group of rocky islets lying on the edge of the continental shelf about 100 miles north-east of Taiwan (in Japanese Senkaku-island, Diaoyu Islands in Chinese). 4

In 2006, South Korea launched a 15-year military-modernization program projected to cost some $550 billion, with about one-third slated for arms purchases. In 2012 it tested cruise missiles with a range of 930 miles, able to reach any location in North Korea. In view of the latest clashes with North Korea more money is to be made available for additional weapons.5

Australia is increasing its armaments budget, and has agreed to the deployment of an additional 2500 US soldiers and the construction of a new US base in the country.

2 Sources:

defensetech.org/2011/05/19/pla-chinese-military-doesnt-compare-to-u-s-military;

csis.org/press/csis-in./panetta-outlines-us-military-strategy-asia;

https://www.globalsecurity.org/military/world/china/budget.htm [7]

Shen Dingli in Le Monde Diplomatique, May 2012

4 factsanddetails.com/japan.php?itemid=819&catid=22&subcatid=148

South China Sea: first link in a chain of conflicts

- 2001 reads

“It not only contains oil and gas resources strategically located near large energy-consuming countries but also is the world's second busiest international sea lane that links North-East Asia and the Western Pacific to the Indian Ocean and the Middle East, traversing the South China Sea. More than half of the world's shipping tonnage sails through the South China Sea each year. Over 80% of the oil for Japan, South Korea and Taiwan flows though the area.

Jose Almonte, former national security adviser to the Philippine government, is blunt about the strategic importance of the area: The great power that controls the South China Sea will dominate both archipelagic and peninsular Southeast Asia and play a decisive role in the future of the western Pacific and the Indian Ocean – together with their strategic sea lanes to and from the oil fields of the Middle East.”1

The South China Sea is not only a vital shipping lane, it is also estimated to be rich in oil, natural gas, precious raw materials and fisheries whose rights of exploitation have not been agreed. These military-strategic, economic factors create an explosive mixture.

The South China Sea is not only a vital shipping lane, it is also estimated to be rich in oil, natural gas, precious raw materials and fisheries whose rights of exploitation have not been agreed. These military-strategic, economic factors create an explosive mixture.

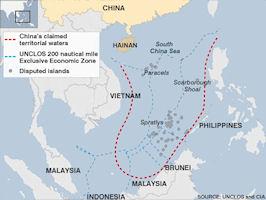

The conflicts between the littoral states over the domination in this zone is not new. In 1978 Vietnam and China clashed over the control of the Spratly islands (Vietnam, which was supported by Moscow at the time, claimed the Spratly islands for itself, the Chinese leader Deng Tsiao Ping warned Moscow that China was prepared for a full-scale war against the USSR). China's more aggressive stand took another turn after 1991 when China took the first steps to fill the power vacuum created by the withdrawal of US forces from the Philippines in 1991. China revived its "historical" claims to all the islets, including the Paracel and Spratly archipelagos, and 80% of the 3.5 million km2 body of water along a nine-dotted U-shaped line, notwithstanding a complete absence of international legal justification. Despite negotiations no resolution has been forthcoming over the two large island groups—the Paracels (or Xisha and Zhongsha), over which China clashed again with Vietnam in 1988 and 1992. The islets can be used as air and sea bases for intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance activities, and as base points for claiming the deeper part of the South China Sea for Chinese missile submarines and other vessels. China is reported to be building an land-sea missile base in southern China’s Guangdong Province, with missiles capable of reaching the Philippines and Vietnam. The base is regarded as an effort to enforce China’s territorial claims to vast areas of the South China Sea claimed by neighbouring countries, and to confront American aircraft carriers that now patrol the area unmolested. China has even declared the zone as “a core interest” - raising it to the same level of significance as Tibet and Taiwan.

The SCS is the most fragile, the most unstable zone because China does not compete with just one big rival. It faces a number of smaller and weaker countries – Vietnam, Philippines, Brunei, Malaysia, Singapore, Indonesia – all of which are too small to defend themselves alone. As a result all the neighbouring countries have to look for help from a bigger ally. This means first and foremost the USA, but also Japan and India which have offered these states their “protection”. The latter two countries have participated in a number of manoeuvres in the area, for example with Vietnam and Singapore.

A main focus of the arms race which has been triggered in Asia can be seen in the SCS countries. Although Vietnam does not have the military and financial means to go toe-to-toe with China, it has been purchasing weapons from European and Russian companies – including submarines. Arms imports are on the rise in Malaysia. Between 2005 and 2009 the country increased its arms imports sevenfold in comparison to the preceding five year period. The tiny city-state of Singapore, which plans to acquire two submarines, is now among the world's top 10 arms importers. Australia plans to spend as much as $279 billion over the next 20 years on new subs, destroyers and fighter planes. Indonesia wants to acquire long-range missiles and purchase 100 German tanks. The Philippines are spending almost $1 billion on new aircraft and radar. China has about 62 submarines now and is expected to add 15 in coming years. India, South Korea and Vietnam are expected to get six more submarines apiece by 2020. Australia plans to add 12 over the next 20 years. Singapore, Indonesia and Malaysia are each adding two. Together, the moves constitute one of the largest build-ups of submarines since the early years of the Cold War. Asian nations are expected to buy as many as 111 submarines over the next 20 years.2

2 (www.wsj.com [11] - February 12,2011)

Another hotspot: the Indian Ocean…

- 1840 reads

The Pacific and the SCS are not the only theatre of imperialist rivalries: the Indian Ocean is becoming another area of confrontation.

The sea lanes in the Indian Ocean are considered among the most strategically important in the world—according to the Journal of the Indian Ocean Region, more than 80% of the world’s seaborne trade in oil transits through Indian Ocean bottlenecks, with 40% passing through the Strait of Hormuz, 35% through the Strait of Malacca and 8% through the Bab el-Mandab Strait. Half the world’s containerized cargo sails through this vital waterway. It is not just a question of sea lanes and trade, however. More than half the world’s armed conflicts are presently located in the Indian Ocean region. In addition to being the theatre of the imperialist ambitions of China and India, there is the permanent threat of a potential nuclear confrontation between India and Pakistan, US interventions in Iraq and Afghanistan, permanent conflict around Iran, Islamist terrorism, increasing piracy in and around the Horn of Africa, and conflicts over diminishing fishery resources.

In fact the Indian Ocean is a crucial “interface” between the zone of imperialist tensions in the Middle East and rising tensions in the Far East, the South China Sea, and the broader Pacific. Although it has been speculated that the Indian Ocean might contain 40% of the world’s oil reserves, and there is fresh exploration for oil in the seas of India, Sri Lanka and Burma, the Ocean's importance has increased since the relative decline of US power in the region has left a void that is increasingly being filled by China and India.

China is not the only country enhancing its presence in the Indian Ocean. Japan is eager to participate in the efforts to contain China and has promised Burma, Thailand, Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia $7.18 billion in development aid over the next three years to help build up infrastructure, including high-speed rail, port and water supply projects. But it is above all India, the biggest country on the littoral which has traditionally had a land-oriented strategic outlook, that has been obliged to counter China's penetration into the Indian Ocean. Much is at stake for India: India imports some 70% of its oil and gas, and some two-thirds of this travels through the Indian Ocean. India is the fourth-largest consumer of oil in the world, and it relies on crude shipments from Middle Eastern countries including Saudi Arabia and Iran. It also imports large amounts of coal from Indonesia and Australia. These dependencies and the crucial role of the sea lanes along its shores have made India very vulnerable from the sea. And of course, India's emergence as a new regional player has increased its imperialist appetite.

India – firmly in the grip of militarist cancer

- 2100 reads

Historically, India was considered the crown jewel of the British empire. When after World War II the British colonial rulers could no longer control India, they divided it. Almost at the same time as Korea and China, the old Raj was divided in two – into a Muslim dominated Pakistan and a multi-religious India with a Hindu majority.1 The two countries have been engaged in a permanent cold war, and four hot wars, ever since.

No sooner was independence declared in 1947 than a military conflict with the rival Pakistan erupted for control of the strategically vital and disputed territory of Kashmir. Pakistan occupied one third of Kashmir while India occupied three fifths (a part of Kashmir is still occupied by China). In the Indo-Pakistani War of 1965 India attacked Pakistan on all fronts after attempts by Pakistani troops to infiltrate into Indian-controlled Kashmir. The Indo-Pakistani War of 1971 was fought over the issue of self rule in East Pakistan; Pakistan was decisively defeated, resulting in the creation of Bangladesh.2

In 1999 Pakistan and India fought an 11-week-long border skirmish in the disputed northern Kashmir province. And during the past years repeated terrorist attacks – supported by Pakistan – have contributed to maintain the hostility between the two nuclear powers.

At the time of India's independence, the Indian ruling class was still able to keep clear of the emerging confrontation between the US-led Western and Russian led Eastern bloc. India took part in setting up the “non-aligned movement”, basically because the main line of confrontation between the two blocs was in Europe and in the Far East (e.g. the Korean war). Since membership of the non-aligned nations3 cut India off from US military support, it was forced to turn to Russia for military equipment and supplies, and even for some industrial investment, though the country was never part of the Russian bloc. However, India's attempt to keep out of the East-West confrontation could not prevent a clash with China, and in 1962 the two countries were engaged in the brief Sino-Indian War over the border in the Himalayas. The war convinced the Indian military to refocus on rearmament and an improvement in relations with the United States.

Thus India faces two arch enemies, Pakistan and China, with China heavily supporting Pakistan. Despite various diplomatic efforts the border disputes between India and China have not disappeared. India claims that China occupies more than 14,000 square miles of Indian territory in the Aksai Chin along its northern border in Kashmir (commonly referred to as the western sector), while China lays claim to more than 34,000 square miles of India’s north-eastern state of Arunachal Pradesh (commonly referred to as the eastern sector). India also is a long-term host to the Dalai Lama and about 100,000 Tibetan refugees who fled China's annexation of Tibet in 1950. In recent years China has also intensified its military build up along the Indian border, in particular in Tibet. For example the PLA Air Force has established at least four airbases in Tibet and three in southern China capable of mounting operations against India.4

With the exception of the British, India's rulers have historically had a land-based outlook. Since India's independence, all the major conflicts in which it has been involved, or which have broken out in the region (Afghanistan, Iraq, Iran) have taken place on land, without any major sea battles. The rapid development of Indian naval power is thus a recent phenomenon and can only be explained by the global confrontation unfolding in Asia. Having focused mostly on the threat from Pakistan and China on its north-eastern flank, India is now faced with an additional challenge – defending its position in the Indian Ocean.5

It is therefore no surprise that India has ordered 350 T-90S tanks (from Russia) as well as some 250-300 fighter planes, and that it has decided to produce some 1000 tanks in India itself.6

To counter China's "string of pearls" strategy the Indian Navy is growing longer sea legs by acquiring aircraft carriers, tankers and troop ships. Over the next decade, India plans to introduce 100 new warships to its naval forces. India now has the world’s fifth-largest navy. Whereas India continues to modernise its territorial forces and needs to keep thousands of troops mobilised at its border with Pakistan, the Chinese military has put even more emphasis on its blue water navies and increasing its out-of-area ballistic capabilities.

Being inferior to China on a military and economic level, Chinese expansion into the Indian Ocean has compelled India to look for an ally whose interests are also opposed to those of China; hence the convergence of interests between the USA and India. It is revealing that India, which in the 1950s could stay out of the major East-West conflict is now being pulled into a power struggle with China and forced to side with the USA. India already holds more joint military exercises annually with the US than any other nation. Despite strong hesitations amongst certain parts of the Indian ruling class, which are suspicious of the USA after so many years of close ties with the Soviet Union, India and the USA are condemned to “partnership”. The USA have no choice but to foster the modernisation and arming of India. In this context they have tacitly or directly supported steps towards developing the Indian nuclear industry – which can only be seen by both Pakistan and China as a direct threat.

“Firstly, the geo-strategic rationale for an alliance between the US and India is the encirclement or containment of the People’s Republic of China, India can be the only counter-weight to China in the region. The other rationale or intentions of such cooperation are the neutralization of Russia as a player in Central Asia and the securing of energy resources for both the US and India. The US also has used India in its objective of trying to isolate Iran.”.7

“Firstly, the geo-strategic rationale for an alliance between the US and India is the encirclement or containment of the People’s Republic of China, India can be the only counter-weight to China in the region. The other rationale or intentions of such cooperation are the neutralization of Russia as a player in Central Asia and the securing of energy resources for both the US and India. The US also has used India in its objective of trying to isolate Iran.”.7

Much like China and the South-East Asian countries, India has intensified its arms build-up. India's defence budget, which was roughly $32 billion in 2011, has increased 151% in the last decade. India's defence spending will rise by 17% in the financial year 2012-13, and the government expects military spending to grow at about 8.33% annually in coming years. India’s import of major weapons increased by 38% between 2002-2006 and 2007-2011. India purchased some $12.7 billion in arms, 80 percent of that from Russia, during 2007-2011, according to the SIPRI.8

India has established listening posts in northern Madagascar, the Seychelles, and Mauritius; in late 2009, it successfully co-opted the Maldives as part of its southern naval command. India has established its first military base on foreign soil at Ayni in Tajikistan. In this context the latest tests of long-range missiles are part of this global strategy of Indian imperialism.

India has started to develop closer economic and above all military ties with other countries that feel threatened by China, notably Japan and Vietnam. India has prioritised strengthening relations with Japan through increasing military contacts, maritime cooperation, and trade and investment ties. Tokyo in turn has pledged $4.5 billion in soft loans for the Delhi-Mumbai railway freight corridor. A joint security declaration with Japan was signed in 2008, calling their partnership “an essential pillar for the future architecture of the region.”9 Japan participated repeatedly in the Malabar naval exercises in the Indian Ocean. India feels particularly threatened not only by the Pakistan-China connection, but it is also alarmed by China's major financial and military support to the strategically important Sri Lanka. The attitude of the Myanmar regime, which for years had privileged links with China, is another factor of uncertainty. Thus India is faced on its western, northern, southern and eastern side and all along its shores by increased pressure from China. As we mentioned above, the Indian army is locked down in a permanent defence of its land borders. China makes periodic incursions into the Indian state of Arunachal Pradesh, which borders Tibet and is claimed by Beijing. China has countered US support for Indian nuclear power by the sale of two new nuclear reactors to Pakistan. Furthermore, the PLA has a presence in the Pakistan-administered Kashmir areas of Azad Kashmir and Gilgit-Baltistan. With China already controlling one fifth of Jammu and Kashmir, the Indian army is facing the reality of a Chinese presence on both the eastern and western flanks of the volatile Kashmir region.

As we shall see below, the contradicting interests in the Indian Ocean and the strategy of arming and looking for allies contains many unpredictable elements. For example early 2008 India launched an Israeli spy satellite (TechSAR/Polaris) into space. The Israeli satellite seems to be mainly aimed against Iran. Israel is supplying India with the latest electronic technology and there are indications which point to a closer cooperation between the USA-India-Israel.10 In this context of growing tensions in Asia India is an important player in a major naval build-up running from the coastline of East Africa and the Arabian Sea to Oceania. Apart from major presence the fleets of the US and its NATO allies in the Indian Ocean, the naval fleets of Iran, India, China, Japan, and Australia have been expanding, using the real problem of piracy in the region to justify their increased presence.11 An international overview shows that while the old industrial countries, suffocating under the crushing weight of the economic crisis, have been forced to reduce or freeze their armaments expenditure, all the emerging Asian countries are relentlessly increasing their arms spending. According to the latest figures released by the SIPRI, the world's five largest arms importers in 2007-2011 were all Asian states. India was the world's single largest recipient of arms, accounting for 10% of global arms imports, followed by South Korea (6%), Pakistan (5%), China (5%) and Singapore (4%). These five countries accounted for 30% of the volume of international arms imports, according to the SIPRI. This simultaneous build-up of advanced weaponry in the Asia-Pacific and South-East-Asia region is on a scale and at a speed not seen since the Cold War arms race between the USA and the Soviet Union.

While tensions rise in East-Asia and South-East Asia, the recent sharpening of tensions in the Middle East makes it very likely that any escalation of conflicts in the Middle East and its surrounding zone will have strong repercussions on the imperialist constellation in Asia.

1 The partition was one of history's biggest operations of ethnic cleansing, displacing up to 10 million people and leaving up to a million dead.

2 en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Indo-Pakistani_wars_and_conflicts

3 The Non-Aligned Movement was founded in 1961 in Belgrade by the leaders of Yugoslavia, Egypt, India, and Indonesia. It attempted to create a space between the two blocs by playing off one against the other. Its room for manoeuvre can be judged by the fact that Castro's Cuba – at the time totally dependent on Russia aid for its survival – was also a member.

6 Sources:

https://www.defenseindustrydaily.com/indian-army-wants-to-add-another-1000-t90s-tanks-by-2020-updated-02697/ [14]

https://www.asian-defence.net/2011/10/india-clears-275-mn-order-for-t-72... [15]

7 See www.globalresearch.org [16], October 17, 2009, Geo-strategic Chessboard: War Between India and China? By Mahdi Darius Nazemroaya.

8 Stockholm International Peace Research Institute https://www.sipri.org/media/pressreleases/rise-in-international-arms-tra... [17]

The oldest hotspot and the danger of contagion towards the East

- 1482 reads

During the past 60 years the Middle East has been the theatre of unending conflicts and wars (Israel-Palestine, Afghanistan, Iraq, Iran, and now Syria). Until recently East Asia and South-East Asia were never heavily involved in these conflicts. But more and more the rivalries between the biggest Asian powers and the antagonism between the USA and China can also be felt in the different conflicts in the Middle East.

Pakistan is courted by both the USA and China. The USA needs Pakistan to counter the different brands of terrorism which operate in Pakistan and in Afghanistan. Yet, not all factions of the ruling cliques in Pakistan want to submit to the USA. Pakistan's involvement in America's wars is destabilising the country still further (for example the recent air strikes in Pakistan reveal the new strategy to “hit and kill”, targeting “terrorists” but spread the flames to even larger areas within Pakistan), but this works in many ways against China, which wants a strong Pakistan against India.

Concerning Afghanistan, India has been participating at the side of American-led forces in the construction of the “security apparatus” in Afghanistan, while China eyes this with great suspicion. Beijing too has signed major economic contracts with Kabul.

The sharpening of the conflict around Iran has major ramifications for the rivalries in Asia. While Iran until 1978/79 was an important outpost for the US-led bloc against Russia, once the Shah's regime imploded and the Mullahs took over, a strong anti-Americanism developed. The more US hegemony weakened, the more Iran could claim regional power. The Iranian challenge to the USA inevitably had to receive Chinese backing. On an economic level, China has benefited from the space left vacant by sanctions imposed against Iran; China is now Iran’s largest trading partner. While Beijing’s economic engagement with Iran is growing, India’s presence is shrinking. Since 12% of India’s oil is imported from Iran (its second largest supplier after Saudi Arabia), India fears being marginalised in Iran and losing out to China.

Despite Shiite Iran and Sunni Saudi-Arabia being fierce enemies, and despite China's support for the Tehran regime, China has signed a civilian nuclear energy cooperation pact with Saudi Arabia, a country which provides China with almost one fifth of its oil. China must avoid antagonising important oil suppliers. This reflects the versatile Chinese diplomatic practice in the region, having an egg in every basket, no matter how much the different sides may oppose each other. And China’s approach to maintain a balance in its ties with Iran and the Arab Gulf States, reduces India's economic and military options, because the Saudis have also developed special links with Pakistan, whose nuclear programme they funded and fostered for years. It is plausible that Pakistan might covertly transfer nuclear technology to Saudi-Arabia – which must be seen as a big threat to Iran and India. However, other additional factors make the constellation more complicated and more contradictory.1

Iran faces many enemies in the region. For example heavily armed Saudi-Arabia (which is planning to buy 600-800 German built tanks and which recently signed a gigantic contract for another 130 modern fighter planes with the USA),2 and Iraq, with whom it waged an 8 year war in the 1980s. Israel feels vulnerable to an Iranian (nuclear?) missile attack and has been pressing the USA hard to strike militarily against alleged Iranian nuclear sites. Thus any escalation around Iran is likely to create great upheavals amongst Iran's rivals and their respective defenders.

Last but not least any conflict in the Middle East draws the former bloc leader Russia onto the stage. Ganging up with China Russia fiercely opposes any military intervention against Iran and does everything it can to undermine US strategy. Both China and Russia must protect Iran against US pressure, because if the regime in Tehran fell, this would strengthen the US position in the Middle East and not only threaten Chinese oil supplies but weaken the Russian and Chinese strategic standing in the region altogether.

The stalemate of the imperialist situation in Syria during the summer of 2012 cannot be understood without the covert and overt weight of China, Russia and Iran in the conflict. Without the support of these three powers, the Western countries – despite their differences and other factors making them hesitate – might be tempted to intervene militarily much faster.

The chaotic and contradictory nexus of imperialist rivalries in the Middle East, where conflicts between the regional power Iran (backed by China and Russia) and the USA (backed by Israel, India, Saudi-Arabia) and increased tensions between local rivals would have unpredictable consequences not only for the rivalries between India and China, but for the whole planet.

While the tensions in the Middle East have been centre-stage in imperialist rivalries for several decades, the tensions in the Far East and in South Asia are rapidly gaining momentum. Although an immediate escalation of the rivalries into an open war in the Far East may not be likely now, because we are only at the beginning of this race, the permanent, irreversible military build-up already forebodes a new level of destruction .

The consequences of militarism

- 3992 reads

In Asia we are not witnessing the clash between secondary powers but between the world's two most populous countries: China and India. At the same time, the world's two biggest economies, the USA and China, who are more dependent on each other on an economic and financial level than ever, are engaged in an arms race. The zone of conflict involves some of the most important sea lanes of the world and contains the long-term risk of spreading a ring of fire from the Far East to the Middle East, with unpredictable repercussions for the entire world economy. Whereas in World War I the main battles took place in Europe and only very marginally in Asia, now one century later, the whole of Asia with its two oceans and its crucial sea-lanes is becoming engulfed in the deadly spiral. The build-up of destructive capacity dwarfs the power of the atomic bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. More than 60 years later, in addition to the USA, half a dozen countries in the region have nuclear weapons or aim at having them: China, India, Pakistan, North Korea, Iran, Russia.1

The USA, the world’s only remaining super-power, feels most threatened by the emergence of China. This has compelled it to reorient its military strategy. While so far 40% of the US navy has been operating in the Atlantic Ocean, Washington plans to deploy 60% of the US navy in Asia. President Obama's recent decision to “pivot” US power towards the East has led to a redeployment of 60% of US naval forces to the Pacific. The US must necessarily do everything in its power to contain China, and so must adapt militarily. In a certain sense for the USA this confrontation is a battle for life or death.2

In March 1946, Winston Churchill delivered his famous "Iron Curtain" speech, describing Soviet domination of Eastern Europe: the expression entered common parlance for the next 43 years, until the collapse in 1989 of the bloc built around the USSR. Only a month previously (February 1946) George Kennan (based in America's Moscow embassy) set out his proposals for the "containment" of the USSR – proposals that were to lay the foundation of US policy towards Russian imperialism. These two key moments illustrate an important feature of imperialism in capitalism's decadent epoch: the formation of fixed imperialist blocs is to a great extent dependent, not so much on common interests as on a common fear of a threatening rival. The "Allied" bloc that confronted the Germany-Italy-Japan "Axis" only really came into being in 1941 – the year that Roosevelt signed the Lend-Lease agreement that guaranteed US arms shipments to Britain, and that Russia entered the war following its invasion by Germany (Operation Barbarossa), and the opening of the war in the Pacific following Japan's attack on Pearl Harbor.

The "Allied" bloc lasted only five years, and ceased to exist with the annihilation of Nazi Germany and the "Axis", to be replaced by a new confrontation between a Russian bloc based on the military occupation of its neighbours (enforced by invasion where necessary: Hungary 1956, Czechoslovakia 1968), and a US bloc based essentially on a common fear of the USSR. When the disintegration of the USSR ended the Cold War with a clear American victory, the glue that had held the US bloc together lost its former holding power, and the US bloc in turn broke apart.

The US remains the world's overwhelmingly dominant power, with a total military budget great than that of the ten next-largest powers combined (45.7% of total world military spending). Nonetheless, China's regional rise poses a real potential threat to its neighbours: the "common fear" factor is overcoming old enmities and pushing towards a series of alliances and rapprochements aimed at containing Chinese power.3 Clearly, there are two powerful poles in the region – China and the United States – and other countries tend to gravitate around them.

Some of these alliances are apparently stable: China's alliance with Pakistan and North Korea, and the India-Japan-USA-Australia grouping. Outside these, however, there is a shifting landscape of regional rivalries: Vietnam and the Philippines fear China, but have their own territorial disputes in the SCS; Cambodia has a troubled history of conflict with Vietnam; Indonesia fears Australia's interference since the independence of East Timor; Sri Lanka and Bangladesh have reason to fear an over-mighty India, and so on. Russia's recent alliance with China in its disputes with the US over Syria and Iran, and North Korea, is essentially opportunistic.4

What we have today, therefore, is not the imminent formation of a new system of imperialist blocs, but rather the emergence of some of the same strategic and political tendencies that have led to the formation of the previous military blocs. There is however one major difference. The previous bloc systems were mostly autarchic in relation to each other (trade between COMECON and the OECD countries, or between China under Mao and the outside world, was insignificant). China and the US, and indeed all the countries of SE Asia, are on the contrary bound together by powerful commercial and financial ties and interests.

What we have today, therefore, is not the imminent formation of a new system of imperialist blocs, but rather the emergence of some of the same strategic and political tendencies that have led to the formation of the previous military blocs. There is however one major difference. The previous bloc systems were mostly autarchic in relation to each other (trade between COMECON and the OECD countries, or between China under Mao and the outside world, was insignificant). China and the US, and indeed all the countries of SE Asia, are on the contrary bound together by powerful commercial and financial ties and interests.

And of all these dependencies, those between China and the USA are the strongest. China holds more US-bonds than any other country ($1.15 trillion), thanks to which US capital has been able to finance its astronomic deficit budget, helping to stave off the effects of the crisis and of course financing its military machine. At the same time, China needs the USA as an export market for its commodities. And yet the two countries consider each other as their main global rivals, against whom they have to mobilise. The South China Sea littoral countries all depend on China as a market for their products and on Chinese investments in their economy, and China needs these countries as well, as suppliers of raw materials and as markets.

Surely it is absurd to imagine countries so dependent on each other engaging in military confrontation, "cutting off their nose to spite their face" so to speak?

Such ideas are not new, indeed they date back to the beginning of the 20th century when the danger of imperialist confrontation was an immediate and burning issue. In his 1902 study of imperialism, the British economist John Hobson denounced imperialism as the fruit of the economic domination of finance capital, and thought that the development of a true, vigorous democracy could act as an antidote to its dangers. In 1909, the future Nobel Peace prize winner Norman Angell, another British economist, published Europe's optical illusion, in which he demonstrated that the economic interdependence of the European powers made imperialist war a mutually ruinous, indeed an irrational undertaking.

Hobson and Angell in effect posed the possibility of a "peaceful" imperialism, or a capitalism stripped of its imperialist defects. Similar notions found their way into the workers' movement prior to 1914: Kautsky imagined the emergence of a "super-imperialist" general alliance of the great powers, whose premises, he thought, could be seen in the cooperation between the European powers (with Japan and the USA) to put down the Boxer rebellion in China.

Lenin gave short shrift to Kautsky and Hobson in his Imperialism, the highest stage of capitalism: "in the realities of the capitalist system (...) 'inter-imperialist' or 'ultra-imperialist' alliances, no matter what form they may assume, whether of one imperialist coalition against another, or of a general alliance embracing all the imperialist powers, are inevitably nothing more than a 'truce' in periods between wars. Peaceful alliances prepare the ground for wars, and in their turn grow out of wars; the one conditions the other, producing alternating forms of peaceful and non-peaceful struggle on one and the same basis of imperialist connections and relations within world economics and world politics". Yet in a sense, both Lenin and Angell were correct: Angell showed that war within an advanced capitalist economy could only lead to catastrophe, while Lenin demonstrated (as Luxemburg had before him) that imperialist conflict was notwithstanding inherent to capitalism "in its death throes" (to use Lenin's expression).

The situation in South-East Asia offers a striking illustration of this dual reality. The smaller countries of the region are all dependent on each other and on China economically and yet all perceive their big neighbour China as a major threat and spend prodigious sums of money arming against China! Why does China antagonise all these countries although it is so dependent on on them economically and financially? Why do so many national bourgeoisies turn towards the USA for “help”, knowing that they run the risk of being blackmailed by the USA? This brings up the deeper question of why there is a permanent drive towards militarism? The military question is “imposing” itself – seemingly even against the will of some factions in the ruling classes of these countries.

The root of the problem is that the economic emergence of a country must necessarily be accompanied by military power. A mere stronger economic competitiveness in the long-term is not sufficient. Every country has to have sufficient access to raw materials, energy, has to benefit from the best flow of commodities, i.e. keep its sea lanes and other transport routes free. No country, whether on the decline or “emerging”, whether a former “loser” or “winner” can escape from this inherent tendency of capitalism.

When capitalism was still in its ascendant phase, expanding across the globe, this situation could lead to tension, even conflict (between Britain and France during the American War of Independence or in India, for example), but not to the all-out destruction of 20th century warfare.5 Today the situation is very different: the entire planet is parcelled out among the various imperialist powers, great and small, and the rise of one power can only be at the expense of another – there are no "win-win" situations.

This is not only true on the level of economic wealth and military hardware. Human action is also determined by more intangible factors – which are none the less material for all that. And in international affairs, national prestige is as important as the possession of military power itself, since a nation's prestige makes its threat of force convincing, giving it the power (to use a favourite expression of British diplomacy) to "punch above its weight". The Byzantine Empire survived long after the decline of its military power, in part thanks to the prestige of its wealth and the name of Rome. Nearer to our own time, first the Bolsheviks and then – after the defeat of the Russian revolution – the Stalinist rulers of the USSR, consistently overestimated the power of a British Empire critically weakened by World War I. Even at the end of World War II, the United States thought for a while that they could leave British armies to hold the line against the USSR in Europe, such was the lasting power of the British imperial myth.6

The capacity for vast and extravagant display is crucial to prestige – hence the colossal expenditure of at least $16 billion on the 2008 Olympic Games in Beijing.7 More important though is the ability to exercise military dominance, especially of one's own immediate area.

Hence, at the beginning of the imperialist age, it was the rising power Germany which set out to challenge the dominant British imperialism by embarking (in 1898) on an ambitious plan of naval expansion aimed explicitly at challenging the power of the Royal Navy. This was, and could only be perceived by Britain as a mortal threat to its own sea lanes and trade, on which the country was and is wholly dependent.

The parallel with today's situation is striking, even down to the imperialist powers' protestations of their peaceful intentions. Here is the German Chancellor von Bülow speaking in 1900: "I explained (...) that I understand by a world policy merely the support and advancement of the tasks that have grown out of the expansion of our industry,our trade, the labour power, activity and intelligence of our people. We had no intentions of conducting an aggressive policy of expansion. We wanted only to protect the vital interests that we had acquired, in the natural course of events, throughout the world".8 And here is Hu Jintao in 2007: "the Chinese government and people will always hold high the banner of peace, development and cooperation, pursue an independent foreign policy of peace, safeguard China's interests in terms of sovereignty, security and development, and uphold its foreign policy purposes of maintaining world peace and promoting common development (...) China opposes terrorism, hegemonism and power politics in any form and does not engage in arms race or pose a military threat to any other country, and will never seek hegemony or engage in expansion".9

As we have demonstrated in this article, China has embarked on a vast programme of rearmament and naval expansion with the aim of dominating its own "inner island chain". All the protestations of China's leadership notwithstanding, this inevitably threatens the whole US position in the Pacific and puts at risk not just its shipping and trade, but its prestige and credibility as an ally, amongst the South-East Asian countries which also feel menaced by China's rise, in particular Japan, South Korea, Vietnam and the Philippines. That America is aware of this threat is clearly demonstrated by Obama's "pivot" of US military power towards the Pacific. Almost 100 years since World War I, capitalism has not changed its nature: capitalist competition in its decadent phase poses more than ever a mortal threat to humanity's survival. The responsibility of the world working class, the only power capable of stopping imperialist war, has never been greater.10

Dv/Jens, November 2012

2 (see Le Monde Diplomatique, March 2012, Michael Klare).

3 The case of Vietnam illustrates the tendency. Vietnam, which was colonised by France and suffered from carpet bombings of all kinds by the USA for more than a decade, in the face of the new giant China has started to look for support from the USA and has, for instance, opened its harbour at Cam Ranh Bay to foreign navies, pulling in other countries (in particular the USA, India, Japan) to develop more muscle against China. The Myanmar ruling junta's sudden love affair with "democracy" after years under China's wing, could also be seen as an attempt to win US and Western support against an over-might neighbour.

4 The different regroupments around China and the US, unlike the old bloc system, remain for the moment a largely regional affair despite China's interests in African and the Middle East, and the European powers' nervousness confronted with the Russian bear.

5 The Napoleonic Wars which lasted for 20 years, might be thought to contradict this, However, these are probably better seen as a continuation of the French revolution and of the revolutionary overthrow of feudalism in Europe, rather than as a war between capitalist powers, though inevitably they also contained aspects of the latter.

6 We have already raised this point in an article on the Apollo space programme [22].

7 This is not new: one could take a "history of prestige" at least as far back as the potlatch ceremonies of North American Indian tribes, if not further.

8 Quoted in EJ Hobsbawm, The Age of Empire, Cardinal Editions p302.

9 Cited by Xinhua, news.xinhuanet.com/english/2007-10/15/content_6884160.htm.

10 An analysis of the class struggle in China is beyond the scope of this article, but we can say that the Chinese capitalist ruling class is aware of the threat from below: China's internal security budget recently overtook its military spending for the first time as Beijing intensified surveillance and repression. In 2012 China will spend $111.4 billion dollars on public security, which includes police and state security forces – an amount that officially exceeds even the defense budget. See https://www.reuters.com/article/2012/03/05/us-china-parliament-security-... [23]