International Review no.147 - 4th Quarter 2011

- 2061 reads

The world economic catastrophe is unavoidable

- 2555 reads

In quick succession over the last few months we have seen a number of important events bearing witness to the gravity of the world economic situation: Greece’s inability to deal with its debts; similar threats to Italy and Spain; warnings to France of its extreme vulnerability in the event of a cessation of payment by Greece or Italy; the paralysis of the US House of Representatives over the issue of raising the debt-ceiling; the USA’s loss of its “Triple A” status – the guarantee of its ability to repay its debts; more and more persistent rumours about the danger of certain banks collapsing, with denials to the contrary fooling nobody given that the same banks have often already imposed massive job-cuts; the first confirmation of the rumours with the failure of the Franco-Belgian bank Dexia. Each time, the leaders of this world have been running after events, but each time the holes they seem to have filled in seem to open up again a few weeks or even days later. Their inability to hold back the escalation of the crisis is less the result of their incompetence and their short-term view than of the current dynamic of capitalism towards catastrophes which cannot be avoided: the bankruptcy of financial establishments, the bankruptcy of entire states, a plunge into deep global recession.

Dramatic consequences for the working class

The austerity measures pushed through in 2010 were implacable, placing a growing part of the working class – and of the rest of the population – in a situation where their most basic needs can no longer be met. To enumerate all the austerity measures which have been introduced in the euro zone, or which are about to be introduced, would make a very long list. It is however necessary to mention a certain number of those that are becoming widespread and which are a significant indication of the lot of millions of the exploited. In Greece, while taxes on consumer goods were increased, the retirement age was raised to 67 and public sector wages were brutally reduced. In September 2011 it was decided that 30,000 public sector workers should be put on technical unemployment with a 40% reduction in wages, while pensions over €1,200 were cut by 20%; the same measure was applied to incomes over €5,000 a year.[1] In nearly all countries taxes have been raised and thousands of public sector jobs axed. This has created many problems in the operation of public services, including the most vital ones: thus, in a city like Barcelona, operating theatres, emergency services and hospital beds have been greatly reduced;[2] in Madrid, 5,000 uncontracted teachers lost their jobs[3] and this was made up for by the contracted teachers having to take on an extra two hours teaching a week.

The unemployment figures are more and more alarming: 7.9% in Britain at the end of August; 10% in the euro zone (20% in Spain) at the end of September[4] and 9.1% in the US over the same period. Throughout the summer, redundancy plans and job-cuts came one after the other: 6,500 at Cisco, 6,000 at Lockhead Martin, 10,000 at HSBC, 3,000 at the Bank of America: the list goes on. The earnings of the exploited have been falling: according to official figures, real wages were going down at an annual rate of 10% by the beginning of 2011, by over 4% in Spain, and to a lesser extent in Italy and Portugal. In the US, 45.7 million people, a 12% increase in a year,[5] only survive thanks to the weekly $30 food stamps handed out by the state.

And despite all this, the worst is yet to come.

All this demonstrates the necessity to overthrow the capitalist system before it leads humanity to ruin. The protest movements against the attacks which have been taking place in a whole number of countries since the spring of 2011, whatever their insufficiencies and weaknesses, nevertheless represent the first steps of a broader proletarian response to the crisis of capitalism (see the article “From indignation to the preparation of class battles” in this issue of the Review).

Since 2008, the bourgeoisie has not been able to block the tendency towards recession

At the beginning of 2010, it was possible to have the illusion that states had succeeded in sheltering capitalism from the continuation of the recession that began in 2008 and early 2009, taking the form of a dizzying fall in production. All the big central banks of the world had injected massive amounts of money into the economy. This was when Ben Bernanke, the director of the FED and architect of major recovery plans was nicknamed “Helicopter Ben” since he seemed to be inundating the US with dollars from a helicopter. Between 2009 and 2010, according to official figures, which we know are always overestimated, the growth rate in the US went from -2.6% to +2.9%, and from -4.1% to +1.7% in the euro zone. In the “emerging” countries, the rates of growth, which had fallen, seemed in 2010 to return to their levels before the financial crisis: 10.4% in China, 9% in India. All states and their media began singing about the recovery, when in reality production in all the developed countries never succeeded in going back to 2007 levels. In other words, rather than a recovery, it would be more accurate to talk about a pause in a downward movement of production. And this pause only lasted a few quarters:

· In the developed countries, rates of growth began to fall again in mid-2010. Predicted growth in the US in 2011 is 0.8%. Ben Bernanke has announced that the American recovery is more or less “marking time”. At the same time, growth in the main European countries (Germany, France, Britain) is near to zero and while the governments of southern Europe (Spain, 0.6% in 2011 after -0.1% in 2010;[6] Italy 0.7% in 2011)[7] have been repeating non-stop that their countries “are not in recession”, in reality, given the austerity plans that they are and will be going through, the perspective opening in front of them is not very different from what Greece is currently experiencing: in 2011, production there has fallen by over 5%.

· In the “emerging” countries the situation is far from brilliant. While they saw important growth rates in 2010, 2011 is looking much gloomier. The IMF has predicted that their growth rate for 2011 will be 8.4%,[8] but certain indices show that activity in China is about to slow down.[9] Growth in Brazil is predicted to go from 7.5% in 2020 to 3.7% in 2011.[10] Finally, capital is starting to flee Russia.[11] In brief, contrary to what we have been sold by the economists and numerous politicians for years, the emerging countries are not going to act as locomotives pulling world growth. On the contrary, they are going to be the first victims of the situation in the developed countries and will see a fall in their exports, which up till now have been the main factor behind their growth.

The IMF has just revised its predictions which had assumed a 4% growth in the world economy in 2010 and 2011: having previously noted that growth had “considerably weakened”, they have now said that we “cannot exclude” a recession in 2012.[12] In other words, the bourgeoisie is becoming aware of the degree to which economic activity is contracting. In the light of all this, the following question is posed: why have the central banks not carried on showering the world in money as they did at the end of 2008 and in 2009, thus considerably increasing the monetary mass (it was multiplied by 3 in the US and 2 in the euro zone)? The reason is that pouring “funny money” into the economy doesn’t resolve the contradictions of capitalism. It results not so much in a recovery of production, but a recovery of inflation. The latter stands at nearly 3% in the euro zone, a bit more in the US, 4.5% in the UK and between 6 and 9% in the emerging countries.

The production of paper or electronic money allows new loans to be agreed... thereby increasing global debt. The scenario is not new. This is how the world’s big economic actors have become mired in debts to the point where they can no longer pay them back. In other words, they are now insolvent, and this includes none other than the European states, America, and the entire banking system.

The cancer of public debt

The euro zone

The states of Europe are finding it increasingly difficult to honour the interest on their debts.

The reason that the euro zone has been the first to see certain states in default of payment is that, unlike the US, Britain and Japan, they don’t control the printing of their own money and so don’t have the opportunity to pay towards their debts in fictional money. Printing euros is the responsibility of the European Central Bank (ECB) which is basically controlled by the big European states and in particular Germany. And, as everyone knows, multiplying the mass of currency by two or three times at a time when production is stagnating only leads to inflation. It’s in order to avoid this that the ECB has become more and more reluctant to finance states that need it; otherwise it risks being in default of payment itself.

This is one of the central reasons why the countries of the euro zone have for the last year and a half been living under the threat of Greece defaulting on its payments. In fact, the problem facing the euro zone has no solution since its failure to finance Greece’s debt will result in a cessation of payment by Greece and its exit from the euro zone. Greece’s creditors, which include other European states and major European banks, would then find it very hard to honour their commitments and would themselves face bankruptcy. The very existence of the euro zone is being put into question, even though its existence is essential for the exporting countries in the north of the zone, especially Germany.

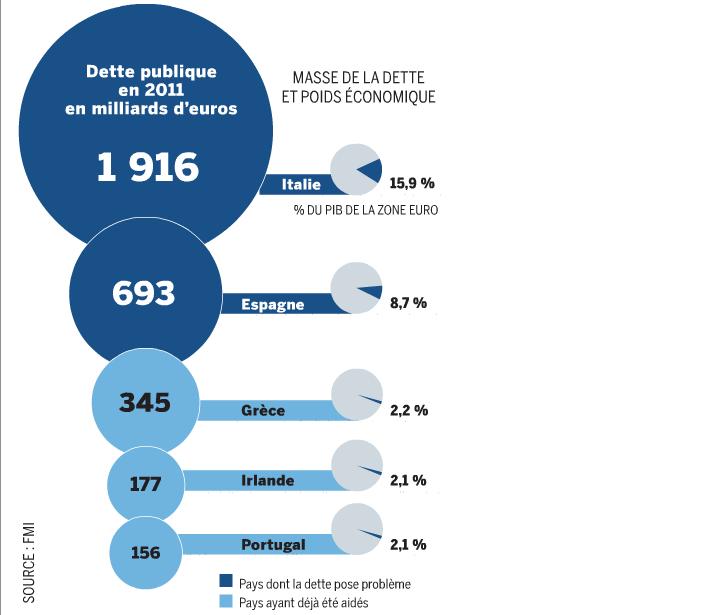

For the last year and a half the issue of defaulting on payments has been focussed mainly on Greece. But countries like Spain and Italy are going to find themselves in a similar situation since they have never found a fiscal recipe for amortising part of their debt (see graph[13]). A glance at the breadth of Italy’s debt, which is very likely to default in the near future, shows that the euro zone would not be able to support these countries to ensure that they could honour their commitments. Already investors believe less and less in their capacity to repay, which is why they are only prepared to lend them money at very high rates of interest. The situation facing Spain is also very close to the one that Greece is now in.

The positions adopted by governments and other euro zone institutions, especially the German government, express their inability to deal with the situation created by the threat of certain countries going bust. The major part of the bourgeoisie of the euro zone is aware of the fact that the problem is not knowing whether or not Greece is in default: the announcement that the banks are going to take part in salvaging 21% of Greece’s debts is already a recognition of this situation, which was confirmed at the Merkel-Sarkozy summit on 9 October which admitted that Greece would default on repaying 60% of its debt. From this point the problem posed to the bourgeoisie is to find a way of making sure that this default will lead to the minimum of convulsions in the euro zone. This is a particularly delicate exercise that has provoked hesitation and divisions within it. Thus, the political parties in Germany are very divided over the issue of how, if they are going to aid Greece financially, they will then be able to help the other states that are rapidly heading towards the same position of default as Greece. As an illustration, it is remarkable that the plan drawn up on 21st July by the authorities of the euro zone to “save” Greece, which envisages a strengthening of the capacity of the European Financial Stability Facility from 220 to 440 billion euros (with the obvious corollary of an increased contribution from the different states), was contested for weeks by an important section of the ruling parties in Germany. After a turn-around in the situation, it was finally voted for by a large majority in the Bundestag on 29th September. Similarly, up till the beginning of August, the German government were opposed to the ECB buying up the titles of Italy and Spain’s sovereign debt. Given the degradation of these countries’ economic situation, the German state finally agreed that from August 7th the ECB could buy up such obligations.[14] So much so that between August 7th and 22nd the ECB bought up 22 billion euros of these two countries’ sovereign debt![15] In fact, these contradictions, these coming and goings, show that a bourgeoisie as internationally important as the German bourgeoisie doesn’t know what policies to carry out. In general, Europe, pushed by Germany, has opted for austerity. But this doesn’t rule out a minimal financing of states and banks via the European Financial Stability Facility (which thus presupposes increasing the financial resources available to this organism) or authorising the ECB to create enough money to come to the aid of a state which can no longer pay its debts and so avoid an immediate default.

Certainly this is not just a problem for the German bourgeoisie but for the entire ruling class, because the whole bourgeoisie has been getting into debt since the 1960s to avoid overproduction, to the point where it is now very difficult not only to pay back the debts but even to pay back the interest on those debts. Hence the economies it is now trying to make via draconian austerity polices, draining incomes everywhere, and at the same time causing a reduction in demand, aggravating overproduction and accelerating the slide into depression.

The USA

The USA was faced with the same kind of problem in the summer of 2011.

The debt ceiling, which in 2008 was fixed at $14,294bn, was reached by May 2011. It had to be raised in order for the US, like the countries in the euro zone, to be able to keep up the payments, including internal ones: the functioning of the state was at stake. Even if the unbelievable stupidity and backwardness of the Tea Party was an element aggravating the crisis, they were not at the root of the problem facing the President and Congress. The real problem was the necessity to choose between two alternatives:

· either carry on with the policy of increasing Federal state debt, as the Democrats argued, which basically meant asking the FED to print money, with the risk of an uncontrolled fall in the value of the dollar;

· or push through a drastic austerity programme, as the Republicans demanded, through the reduction over the next ten years of public expenditure by something between $4,000bn and $8000bn. By way of comparison, the Gross Domestic Product of the US in 2010 was $14,624bn, which gives an idea of the scale of the budget cuts, and thus the slashing of public sector jobs, implied by this plan.

To sum up, the alternative posed this summer to the US was the following: either take the risk of opening the door to galloping inflation, or carry through an austerity programme which could only strongly restrict demand and provoke a fall or even a disappearance of profits: in the long run, a chain reaction of closures and a dramatic fall in production. From the standpoint of the national interest, both the Democrats and the Republicans are putting forward legitimate answers. Pulled hither and thither by the contradictions assailing the national economy, the US authorities have been reduced to contradictory and incoherent half measures. Congress will still be faced with the need both to make massive economic cuts and to get the economy moving.

The outcome of the conflict between Democrats and Republicans shows that, contrary to Europe, the USA has opted more for the aggravation of debt because the Federal debt ceiling was raised by 2100 billion up till 2013, with a corresponding reduction in budgetary expenses of around 2500 billion in the next ten years.

But, as for Europe, this decision shows that the American state does not know what policies to adopt in the face of the debt crisis.

The lowering of America’s credit rating by the rating agency Standard and Poor, and the reactions that followed, are an illustration of the fact that the bourgeoisie knows quite well that it has reached a dead-end and that it can’t see a way out of it. Unlike many other decisions taken by the ratings agencies since the beginning of the sub-prime crisis, Standard and Poor’s decision this summer looked coherent: the agency is showing that there is no recipe to compensate for the increase in debt agreed by Congress and that, as a result, the USA’s capacity to reimburse its debts has lost credibility. In other words, for this institution, the compromise, which avoided a grave political crisis in the US by aggravating the country’s debt, is going to deepen the insolvency of the US state itself. The loss of confidence in the dollar by the world’s financiers, which will be an inevitable result of Standard and Poor’s judgement, will lead to a fall in its value. At the same time, while the vote on increasing the Federal debt ceiling made it possible to avoid a paralysis in the Federal administration, the different states and municipalities are already faced with exactly that problem. Since July 4, the State of Minnesota has been in default and it had to ask 22,000 state employees to stay at home.[16] A number of US cities, such as Central Falls and Harrisburg, the capital of Pennsylvania, are in the same situation, while it looks like the State of California and others will soon be in the same boat

Faced with the deepening of the crisis since 2007, the economic policies of both the US and the euro zone have meant the state taking charge of debts that were originally contracted in the private sector. These new debts can’t fail to increase the overall public debt, which has itself been growing ceaselessly for decades. States are facing a deadline on debt that they can never pay back. In the US as in the euro zone, this will mean massive lay-offs in the public sector, endless wage-cuts and ever-rising taxes.

The threat of a grave banking crisis

In 2008-9, after the collapse of certain banks such as Bear Stearns and Northern Rock and the utter downfall of Lehman Brothers, states ran to the aid of many other banks, pumping in capital to avoid the same fate. What is the state of health of the banks today? It is once again very bad. First of all, a whole series of irrecoverable loans have not been removed from their balances. In addition, many banks themselves hold part of the debts of states that are now struggling to make their repayments. The problem for the banks is that the value of the debts they have taken on has now considerably diminished.

The recent declaration by the IMF, based on a recognition of the current difficulties of the European Banks and stipulating that they must increase their own funds by 200 billion euros, has provoked a number of sharp reactions and declarations from these institutions, claiming that everything was fine with them. And this at a moment when everything was showing the contrary:

American banks no longer want to refinance in dollars the American affiliates of the European banks and have been repatriating fund which they had previously placed in Europe;

European banks are lending less and less to each other because they are less and less sure of being repaid. They prefer to put their liquidities in the ECB, despite very high bank rates; a consequence of this growing lack of confidence is that the rate of interest on inter-bank loans has been climbing continually, even if it has not yet reached the levels of the end of 2008.[17]

The high point was reached a few weeks after the banks proclaimed their wonderful state of health, when we saw the collapse and liquidation of the Franco-Belgian bank Dexia, without any other bank being willing to come to the rescue.

We can add that the American banks are poorly placed to keep the machine going on behalf of their European consorts: because of the difficulties they are facing, the Bank of America has just cut 10% of its workforce and Goldman Sachs, the bank which has become the symbol of global speculation, has just laid off 1,000 people. And they too prefer depositing their liquidities in the FED rather than loaning to other American banks.

The health of the banks is essential for capitalism because it can’t function without a banking system that supplies it with currency. But the tendency we are seeing today is towards another “Credit Crunch”, i.e. a situation where the banks no longer want to loan as soon as there is the least risk of not being repaid. What this means in the long run is a blockage in the circulation of capital, which amounts to the blockage of the economy. From this perspective we can better understand why the problem of shoring up the banks’ own funds has become the first item on the agenda of the various international summit meetings that have taken place, even ahead of the situation in Greece, which has certainly not been resolved. At root, the problem of the banks reveals the extreme gravity of the economic situation and illustrates the inextricable difficulties facing capitalism.

When the US lost its triple A status, the headline of the French economic daily Les Echos of 8th August read: “America downgraded, the world enters the unknown”. When the main economic media of the French bourgeoisie expresses its disorientation like this, when it shows its anxiety about the future, it merely expresses the disorientation of the entire bourgeoisie. Since 1945, western capitalism (and world capitalism after the collapse of the USSR) has been based on the fact that the strength of American capital was the final guarantor of the dollars that ensured the circulation of commodities and thus of capital around the world. But now the immense accumulation of debts contracted by the American bourgeoisie to deal with the return of the open crisis of capitalism since the end of the 1960s has ended up becoming a factor aggravating and accelerating the crisis. All those holding parts of the American debt, starting with the American state itself, are holding an asset which is worth less and less. The currency on which the debt is based can now only weaken the American state.

The base of the pyramid on which the world has been built since 1945 is breaking up. In 2007, when the financial crisis broke, the financial system was saved by the central banks, i.e. by the states. Now the states themselves are on the verge of bankruptcy and it is out of the question that the banks can come along and save them. Whichever way the capitalists turn, there’s nothing that can make a real recovery possible. Even a very feeble rate of growth would require the development of fresh debts in order to create the demand needed to absorb commodities; but even the interest on the debts already taken out is no longer repayable and this is dragging banks and states towards bankruptcy.

As we have seen, decisions that once seemed irrevocable are being put into question in the space of a few days and certainties about the health of the economy are being disproved just as quickly. In this context, states are more and more obliged to navigate from one day to the next. It is probable, but not certain because the bourgeoisie is so disoriented by a situation it has never been in before, that to deal with immediate issues it will continue to sustain capital, whether financial, commercial or industrial, with newly-printed money, even if this gives a new impetus to the inflation that is already on the march and is going to become more and more uncontrollable. This will not stop the continuation of lay-offs, wage-cuts and tax increases; but inflation will more and more make the poverty of the great majority of the exploited even worse. The very day that Les Echoes wrote “America downgraded, the world enters the unknown”, another French economic daily, La Tribune led with “left behind”, describing the planet’s big decision-makers whose photos appeared on the front page. Yes indeed: those who once promised us marvels and mountains, and then tried to console us when it became obvious that the marvel was actually a nightmare, now admit that they have been left behind. And they have been left behind because their system, capitalism is definitively obsolete and is in the process of pulling the vast majority of the world’s population into the most terrible poverty.

Vitaz 10/10/11.

[1]. lefigaro.fr, 9.22.11, “La colère gronde de plus en plus en Grèce”.

[2]. news.fr.msn.com; “Espagne, les enseignants manifestent à Madrid contre les coupes budgetaires”.

[4]. Statistique Eurostat.

[5]. Le Monde, 7-8.8.11.

[6]. finance-economie.com, 10.10 11, “Chiffres clés Espagne”.

[7]. globalix.fr “La dynamique de la dette italienne”.

[8]. IMF, World Economic Outlook Update, July 2010.

[9]. Le Figaro, 3.10.11.

[10]. Les Echos, 9.8.11.

[11]. lecourrierderussie.com, 10.12.11: “Putin, la crise existe”.

[12]. lefigaro.fr, 5.10.11: “FMI, recession mondiale pas exclue”.

[13]. Adapted from Le Monde 5.8.11.

[14]. Les Echos, August 2011.

[15]. Les Echos, 16 August 2011.

[16]. rfi.fr, 2.7.11,”Faillite: le gouvernment de Minnesota cesse activities”

[17]. gecodia.fr “Le stress interbancaire en Europe approche du pic post Lehman”

Rubric:

The Indignados in Spain, Greece and Israel

- 2757 reads

From indignation to the preparation of class struggles

In the editorial of International Review n° 146 [3] we gave an account of the struggles that had developed in Spain.[1]Since then, the contagion of its example has spread to Greece and Israel.[2]

In this article, we want to draw the lessons of these movements and look at what perspectives they hold faced with the bankruptcy of capitalism and the ferocious attacks against the proletariat and the vast majority of the world population.

In order to understand these movements we have to categorically reject the immediatist and empiricist method that dominates society today. This method analyses each event in itself, outside of any historical context and isolated in the country where it appears. This photographic method is a reflection of the ideological degeneration of the capitalist class, because “All that the latter can offer is a day-by-day resistance, with no hope of success, to the irrevocable collapse of the capitalist mode of production.”[3]

A photograph can show us a person with a big happy smile, but this can hide the fact that a few seconds before or after they were grimacing with anxiety. We cannot understand social movements in this way. We can only see them in the light of the past in which they have matured and the future to which they are pointing; it is necessary to place them in their international context and not in the narrow national confines where they appear, and, above all, we have to understand them in their dynamic; not by what they are at any given moment but by what they can become due to the tendencies, forces and perspectives they contain and which will sooner or later come to the surface.

Will the proletariat be able to respond to the crisis of capitalism?

At the beginning of the 21st century we published a series of two articles entitled “Why the proletariat has not yet overthrown capitalism”,[4] in which we recalled that the communist revolution is not inevitable and that its realisation depends on the union of two factors, the objective and subjective. The objective condition is supplied by the decadence of capitalism[5] and by “the open crisis of bourgeois society, clearly proving that capitalist relations of production must be replaced by others.”[6]The subjective factor is related to the collective and conscious action of the proletariat.

The articles acknowledge that the proletariat has previously missed its appointments with history. During the first – the First World War – its attempt to respond with an international revolutionary wave in 1917-23 was defeated; in the second – the Great Depression of 1929 – it was absent as an autonomous class; in the third – the Second World War – it was not only absent but also believed that democracy and the welfare state, those myths used by the victors, were actually victories. Subsequently, with the return of the crisis at the end of the 1960s, it “did not fail to respond but it was confronted by a series of obstacles that it has had to face and which have blocked its progress towards the proletarian revolution.”[7] These obstacles led to a significant new phenomenon – the collapse of the so-called “communist” regimes in 1989 – in which not only was the proletariat not an active factor, but it was the victim of a formidable anti-communist campaign that made it retreat, not only at the level of its consciousness but also its combativity.

What we might call the “the fifth rendezvous with history” opened up from 2007. The crisis is more openly showing the almost definitive failure of the policies that capitalism has put in place to try to respond to the emergence of its insoluble economic crisis. The summer of 2011 made clear that the enormous sums injected cannot stop the haemorrhage and that capitalism is sliding towards a Great Depression far more serious than that of 1929.[8]

But initially, and despite the blows that have rained down on it, the proletariat has appeared equally absent. We foresaw such a situation at our 18th International Congress (2009): “In a historic situation where the proletariat has not suffered from a historic defeat as it had in the 1930s, massive lay-offs, which have already started, could provoke very hard combats, even explosions of violence. But these would probably, in an initial moment, be desperate and relatively isolated struggles, even if they may win real sympathy from other sectors of the working class. This is why, in the coming period, the fact that we do not see a widescale response from the working class to the attacks should not lead us to consider that it has given up the struggle for the defence of its interests. It is in a second period, when it is less vulnerable to the bourgeoisie's blackmail, that workers will tend to turn to the idea that a united and solid struggle can push back the attacks of the ruling class, especially when the latter tries to make the whole working class pay for the huge budget deficits accumulating today with all the plans for saving the banks and stimulating the economy. This is when we are more likely to see the development of broad struggles by the workers.”[9]

The current movements in Spain, Israel and Greece show that the proletariat is beginning to take up this “fifth appointment with history”, to prepare itself to be present, to give itself the means to win.[10]

In the series cited above, we said that the two pillars on which capitalism – at least in the central countries – has relied on to keep the proletariat under its control, are democracy and the so-called “welfare state”. What the three movements show is that these pillars are beginning to be questioned, albeit in a still confused way, and this questioning is being fuelled by the catastrophic evolution of the crisis.

The questioning of democracy

Anger against politicians and against democracy in general has been shown in all three movements, which have also displayed outrage at the fact that the rich and their political personnel are becoming increasing richer and more corrupt while the vast majority of the population are treated as commodities to service the scandalous profits of the exploiting minority, commodities to be thrown in the trash when the “markets are not going well”; the brutal austerity programmes have also been denounced, programmes no one talked about in the election campaigns but which have become the main occupation of those elected.

It is clear that these feelings and attitudes are not new: ranting about politicians for example has been common currency during the last thirty years. It is equally clear that these feelings can be diverted into dead ends, which is what the forces of the bourgeoisie have been insistently trying to do in the three movements: “towards a participative democracy”, towards a “democratic renewal”, etc.

But what is new and of significant importance is that, despite the intentions of those spreading these ideas, democracy, the bourgeois state and its apparatus of domination are the subject of debate in countless assemblies. You cannot compare individuals who ruminate on their disgust, in an atomized, passive and resigned way, with the same individuals who express this collectively in assemblies. Beyond the errors, confusions and dead ends which inevitably find expression and which must be combated with great patience and energy, what is most important is that these problems are being posed publicly; clear evidence of a politicisation of the masses, and also that this democracy, which has rendered capitalism such good service throughout the last century, is now being put into question.

The end of the so-called “welfare state”

After the Second World War, capitalism installed the so-called “welfare state”.[11] This has been one of the principal pillars of capitalist rule in the last 70 years. It created the illusion that capitalism could overcome its most brutal aspects: the welfare state would guarantee security against unemployment, for retirement, provide free health care, education, social housing, etc.

This “social state”, the complement to political democracy, has already suffered significant amputations over the last 25 years and is now heading for its disappearance pure and simple. In Greece, Spain and Israel (where it is above all the shortage of housing that has polarised the young), discontent over the removal of minimum social benefits has been at the centre of the movements. There have certainly been attempts by the bourgeoisie to divert this towards “reforms” of the constitution, the passing of laws that “guarantee” these benefits, etc. But the wave of growing discontent will help to challenge these dykes which are meant to control the workers.

The movement of the Indignants, the culmination of eight years of struggle

The cancer of scepticism dominates ideology today and infects the proletariat and its own revolutionary minorities. As stated above, the proletariat has missed all of the appointments that history has given it during the course of a century of capitalist decadence, and this has resulted in an agonising doubt in its own ranks about its identity and its capacities as a class, to the point where even in displays of militancy some reject the term “working class”.[12] This scepticism is made even stronger because it is fed by the decomposition of capitalism;[13] despair, the lack of concrete plans for the future foster disbelief and distrust of any perspective of collective action.

The movements in Spain, Greece and Israel – despite all the weaknesses they contain – have begun to provide an effective remedy against the cancer of scepticism, as much by their very existence and what they mean for the continuity of struggles and the conscious efforts made by the world proletariat since 2003.[14] They are not a storm that suddenly burst out of a clear blue sky but the result of a slow accumulation over the last eight years of small clouds, drizzle and timid lightning that has grown until it acquires a new quality.

Since 2003 the proletariat has begun to recover from the long reflux in its consciousness and combativity that it suffered after the events of 1989. This process follows a slow, contradictory and very tortuous rhythm, expressed by:

- a series of struggles isolated in different countries in the centre as well as on the periphery, characterised by protests “pregnant with possibilities”; searching for solidarity, attempts at self-organisation, the presence of new generations, reflection about the future;

- a development of internationalist minorities looking for revolutionary coherence, posing many questions, seeking contact with each other, discussing, drawing up perspectives...

In 2006 two movements broke out – the student movement against the Contract of Primary Employment in France and the massive workers’ strike at Vigo in Spain[15] – which, despite their distance, difference in conditions and age, showed similar features: general assemblies, extension to other workers, massive demonstrations... They were like a first warning shot that, apparently, had no follow up.[16]

A year later an embryonic mass strike exploded in Egypt starting in a large textile factory. At the beginning of 2008 many struggles broke out, isolated from each other but simultaneously in many countries, from the periphery to the centre of capitalism. Other movements also stood out, such as the proliferation of hunger revolts in 33 countries during the first quarter of 2008. In Egypt, these were supported and in part taken over by the proletariat. At the end of 2008 the revolt of young workers in Greece exploded, supported by a section of the proletariat. We also saw the seeds of an internationalist reaction at Lindsey (Great Britain) and an explosive generalized strike in southern China (in June).

After the initial retreat of the proletariat faced with the first impact of the crisis – as we pointed out above – much more determined struggles began to take place, and in 2010 France was rocked by massive protest movements against pension reform, with the appearance of inter-professional assemblies; British youth rebelled in December against the sharp rise in student fees. 2011 saw major social revolts in Egypt and Tunisia. The proletariat seemed to gain momentum for a new leap forward: the movement of the “Indignant” in Spain, then in Greece and Israel.

Does this movement belong to the working class?

These three movements cannot be understood outside the context that we have just analysed. They are like a puzzle that brings together all the pieces provided throughout the past eight years. But scepticism is very strong and many have asked: can we talk about movements of the working class if it is not present as such, and if they are not reinforced by strikes or assemblies in the workplace?

The so-called “Indignant” movement is a very valuable concept for the working class[17] but this is not revealed immediately because it does not identify itself directly with its class nature. Two factors give it the appearance of being essentially a social revolt:

The loss of class identity

The working class has gone through a long period of reflux which has inflicted significant damage on its self-confidence and the consciousness of its own identity: “With the collapse of the eastern bloc and the so-called ‘socialist' regimes, the deafening campaigns about the ‘end of communism', and even the ‘end of the class struggle' dealt a severe blow to the consciousness and combativity of the working class; the proletariat suffered a profound retreat on these two levels, a retreat which lasted for over ten years.. At the same time, it [the bourgeoisie] managed to create a strong feeling of powerlessness within the working class because it was unable to wage any massive struggles.”[18] This partly explains why the participation of the proletariat as a class has not been dominant even though it was present through the participation of individual workers (employed, unemployed, students, retired...) who attempted to clarify, to get involved according to their instincts, but who lacked the strength, cohesion and clarity there would be if the class participated collectively as a class.

It follows from this loss of identity that the programme, theory, traditions, methods of the proletariat, are not recognised as their own by the immense majority of workers. The language, forms of action, even the symbols which appear in the Indignants movement derive from other sources. This is a dangerous weakness that must be patiently combated to bring about a critical re-appropriation of the theoretical heritage, experience, traditions, that the workers’ movement has accumulated over the past two centuries.

The presence of non-proletarian social strata

Among the Indignants there is a strong presence of non-proletarian social strata, especially a middle layer that is in the throes of proletarianisation. As for Israel, our article underlined that: “Another tack is to label this as a ‘middle class’ movement. It’s true that, as with all the other movements, we are looking at a broad social revolt which can express the dissatisfaction of many different layers in society, from small businessmen to workers at the point of production, all of whom are affected by the world economic crisis, the growing gap between rich and poor, and, in a country like Israel, the aggravation of living conditions by the insatiable demands of the war economy. But ‘middle class’ has become a lazy, catch-all term meaning anyone with an education or a job, and in Israel as in North Africa, Spain or Greece, growing numbers of educated young people are being pushed into the ranks of the proletariat, working in low paid and unskilled jobs where they can find work at all.”[19]

If the movement appears vague and poorly defined, this cannot put into question its class character, especially if we view things in their dynamic, in the perspective of the future, as the comrades of the TPTG do concerning the movement in Greece: “What the whole political spectrum finds disquieting in this assembly movement is that the mounting proletarian (and petit-bourgeois) anger and indignation is not expressed anymore through the mediation channels of the political parties and the unions. Thus, it is not so much controllable and it is potentially dangerous for the political and unionist representation system in general.”[20]

The presence of the proletariat is visible neither as a force leading the movement, nor through a mobilisation in the workplace. It lies in the dynamic of searching, clarification, preparation of the social terrain, of recognition of the battle that is being prepared. That is where its importance is found, despite the fact that this is only an extremely fragile small step forward.

In relation to Greece, the comrades of the TPTG say that “One thing is certain: this volatile, contradictory movement attracts the attention from all sides of the political spectrum and constitutes an expression of the crisis of class relations and politics in general. No other struggle has expressed itself in a more ambivalent and explosive way in the last decades,”[21] and on Israel, a journalist noted, in his own language, that “it was never oppression that held the social order in Israel together, as far as the Jewish society was concerned. It was indoctrination - a dominant ideology, to use a term preferred by critical theorists. And it was this cultural order that was dented in this round of protests. For the first time, a major part of the Jewish middle class - it’s too early to estimate how large is this group - recognized their problem not with other Israelis, or with the Arabs, or with a certain politician, but with the entire social order, with the entire system. In this sense, it’s a unique event in Israel’s history.”[22]

The characteristics of future struggles

With this vision we can understand the features of these struggles as the characteristics that future struggles will assume with a critical spirit and develop at higher levels:

- the entry into struggle of new generations of the proletariat, with, however, an important difference with the 1968 movements: while the young then gave zero consideration to their “defeated and embourgeoisified” elders, today we see a struggle that unites the different generations of the working class;

- mass direct action: the struggle has won the street, the squares have been occupied. The exploited have found in these a place where they are able to live, discuss and act together;

- the beginnings of politicisation: beyond the false answers that are and will be given, it is important that the great masses are beginning to be directly and actively involved in the great questions of society; this is the beginning of their politicisation as a class;

- the assemblies: they are linked to the proletarian tradition of the workers’ councils of 1905 and 1917, which spread to Germany and other countries during the world revolutionary wave of 1917-23. They reappeared in 1956 in Hungary and in 1980 in Poland. They are the weapon of unity, of the development of solidarity, of the capacity of the proletarian masses to understand and make decisions. The slogan “All power to the assemblies!”, very popular in Spain, expresses the birth of a deep reflection on the key questions of the state, dual power, etc.;

- the culture of debate:the clarity that inspires the determination and heroism of the proletarian masses cannot be decreed, nor is it the fruit of indoctrination by a minority possessed of “the truth”: it is the combined product of experience, of struggle and especially of discussion. The culture of debate has been present in these three movements: everything was up for discussion, nothing that was political, social, economic, human, escaped the critique of these immense improvised ‘town squares’. As we say in the introduction to the article by the comrades in Greece, this has an enormous importance: “a determined effort to contribute towards the emergence of what the comrades of the TPTG call a ‘proletarian public sphere’ which will make it possible for growing numbers of our class not only to work out how to resist capitalism’s attacks on our lives, but to develop the theories and actions that lead to a new way of life altogether”;[23]

- the way to confront the question of violence: “The proletarian movement has been confronted from the beginning with the extreme violence of the exploiting class, with repression when it tries to defend its interests, with imperialist war but also with the daily violence of exploitation. Unlike exploiting classes, the class that is the bearer of communism is not the bearer of violence; and even though it has to make use of it, it does not do so by identifying with it. In particular, the violence it has to use in the overthrow of capitalism, which it will have to use with great determination, is necessarily a conscious and organised violence and must always be preceded by a whole process of growth in consciousness and organisation through the various struggles against exploitation.”[24] As in the students’ movement in 2006, the bourgeoisie has tried on numerous occasions to lead the Indignants movement (especially in Spain) into the trap of violent confrontations with the police in conditions of dispersion and weakness, in order to discredit the movement and facilitate its isolation. These traps have been avoided and an active debate on the question of violence has begun to emerge.[25]

Weaknesses and confusions of the struggle

The last thing we want to do is glorify these movements. Nothing is more alien to the Marxist method than to make a certain struggle, however important and rich in lessons it is, into a definitive, finished and monolithic model that must be followed to the letter. We are perfectly aware of the weaknesses and problems of these movements.

The presence of a “democratic wing”

This strives for the realisation of a “real democracy”. It is represented by various currents, including some of the right as in Greece. It is clear that the media and politicians support this wing in order to try and get the whole movement to identify with it.

Revolutionaries must vigorously struggle against all the mystifications, false measures and false arguments of this trend. But why is there still such a strong tendency to be seduced by the siren songs of democracy after so many years of lies, traps and deceptions? We can point to three reasons. The first is the weight of non-proletarian social layers who are very open to such democratic and inter-classist mystifications. The second is the strength of confusions and democratic illusions still very present in the working class itself, especially among young people who have not yet been able to develop a political experience. Finally, the third is the weight of what we call the social and ideological decomposition of capitalism, that encourages the tendency to seek refuge in an entity that is “above classes and class conflicts” – that is to say the state, which will allegedly bring some order, justice and mediation.

But there is a deeper cause, to which it is necessary to draw attention. In The 18th Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte, Marx states that “proletarian revolutions constantly retreat faced with the enormity of their own aims”. Today, events underscore the bankruptcy of capitalism, the need to destroy it and to build a new society. For a proletariat that doubts its own capacities, that has not yet recovered its identity, this creates and will continue to create for some time the tendency to cling to false hopes, to false measures for “reforms” and “democratisation”, even while doubting them. All this undoubtedly gives the bourgeoisie a margin of manoeuvre that allows it to sow division and demoralisation and, consequently, to make it even more difficult for the proletariat to recover its self-confidence and class identity.

The poison of apoliticism

This is an old weakness which has weighed on the proletariat since 1968 and has its origin in the huge disappointment and profound scepticism provoked by the Stalinist and social democratic counter-revolution, which caused a tendency to believe that all political opposition, including that which claims to be proletarian, is nothing but a vile lie, containing within it the worm of treachery and oppression. This has widely benefited the forces of the bourgeoisie which, hiding their real identity and under the fiction of intervening “as free citizens”, work within the movement to take control of the assemblies and sabotage them from within. The comrades of the TPTG show this clearly: “In the beginning there was a communal spirit in the first efforts at self-organizing the occupation of the square and officially political parties were not tolerated. However, the leftists and especially those coming from SYRIZA (Coalition of Radical Left) got quickly involved in the Syntagma assembly and took over important positions in the groups that were formed in order to run the occupation of Syntagma square, and, more specifically, in the group for “secretarial support” and the one responsible for “communication”. These two groups are the most important ones because they organize the agenda of the assemblies as well as the flow of the discussion. It must be noted that these people do not openly declare their political allegiance and appear as ‘individuals’.”[26]

The danger of nationalism

This is very present in Greece and Israel. As the comrades of the TPTG denounced, “Nationalism (mostly in a populist form) is dominant, favoured both by the various extreme right wing cliques as well as by left parties and leftists. Even for a lot of proletarians or petty-bourgeois hit by the crisis who are not affiliated with political parties, national identity appears as a last imaginary refuge when everything else is rapidly crumbling. Behind the slogans against the ‘foreign, sell out government’ or for the ‘Salvation of the country’, ‘National sovereignty’ and a ‘New Constitution” lies a deep feeling of fear and alienation to which the ‘national community’ appears as a magical unifying solution.”[27]

This reflection by the comrades is as accurate as it is profound. The loss of identity and confidence of the proletariat in its own strength, the slow process through which the struggle in the rest of the world is going, encourages the tendency to “cling on to the national community”, as a utopian refuge faced with a hostile world full of uncertainties.

So for example, the consequences of the cuts in health and education, the real problems created by the weakening of these services, are used to confine the struggles behind nationalist barriers by demanding a “good education” (because it will make us more competitive on the world market), and a “health service for all citizens”.

The fear and difficulty of taking up class confrontations

The frightening threat of unemployment, massive casualisation, the growing fragmentation of employees – divided, in the same workplaces, into an inextricable web of subcontractors and an incredible variety of different terms of employment – have a powerfully intimidating effect and make it more difficult for workers to come together for the struggle. This situation cannot be overcome either through voluntarist calls for mobilization or by admonishing the workers for their alleged “cowardice” or “servility”.

Thus, the step towards the mass mobilization of the unemployed, casual workers, places of work and study, is made much more difficult that it might seem at first sight, causing in turn a hesitation, a doubt and a tendency to cling to “assemblies” which every day are becoming more minoritarian “and whose “unity” favours only the forces of the bourgeoisie who work within them. This gives the bourgeoisie a margin of manoeuvre to prepare its dirty tricks intended to sabotage the general assemblies. And this is precisely what the comrades of the TPTG denounced: “The manipulation of the main assembly in Syntagma square (there are several others in various neighbourhoods of Athens and cities in Greece) by “incognito” members of left parties and organizations is evident and really obstructive in a class direction of the movement. However, due to the deep legitimization crisis of the political system of representation in general they, too, have to hide their political identity and keep a balance between a general, abstract talk about “self-determination”, “direct democracy”, “collective action”, “anti-racism”, “social change” etc on the one hand and extreme nationalism, thug-like behaviour of some extreme-right wing individuals participating in groups in the square on the other hand, and all this in a not so successful way.”[28]

Looking to the future with confidence

While it is clear that “for humanity to survive, capitalism must die”,[29] the proletariat is still very far from having the capacity to execute this sentence. The movement of the Indignants has laid the foundation stone.

In the series mentioned above, we said: “one of the reasons why the revolutionaries where unable to be successful in previous revolutions was that they underestimated the forces of the ruling class, especially its political intelligence.”[30] This capacity of the bourgeoisie to use its political intelligence against the struggles is today stronger than ever! So for example, the Indignants movements in three countries were completely blacked out, except when they were given the veneer of “democratic regeneration”. Likewise, the British bourgeoisie was able to take advantage of the discontent to channel it into a nihilistic revolt that served as a pretext to strengthen repression and intimidate any response from the class.[31]The movements of the Indignant have laid a first stone, in the sense that they have taken the first steps for the proletariat to recover its self-confidence and its class identity, but this is still a long way off because it requires the development of mass struggles on a directly proletarian terrain, which will show that, faced with the bankruptcy of capitalism, the working class is capable of offering a revolutionary alternative to the non-exploiting social layers.

We do not know how this goal will be achieved and we must remain vigilant to the capabilities and initiatives of the masses, like that of 15th May in Spain. What we do know is that the international extension of the struggle will be a key factor in this direction.

The three movements have planted the seed of an internationalist consciousness: when the movement of the Indignants arose in Spain, it said its inspiration was Tahrir Square in Egypt;[32] it sought an international extension of the struggle, although this would be done in the utmost confusion. For their part, the movements in Israel and Greece explicitly stated they were following the example of the Indignants of Spain. Protesters in Israel displayed placards saying, "Mubarak, Assad, Netanyahu: all the same!", which shows not only an awareness of who the enemy is but also at least an embryonic understanding that their struggle is waged with the exploited of these countries and not against them in the framework of national defence.[33] “In Jaffa, dozens of Arab and Jewish protesters carried signs in Hebrew and Arabic reading ‘Arabs and Jews want affordable housing,’ and ‘Jaffa doesn’t want bids for the rich only.’ […] there have been ongoing protests of both Jews and Arabs against evictions of the latter from the Sheikh Jarrah neighbourhood. In Tel Aviv, contacts were made with residents of refugee camps in the occupied territories, who visited the tent cities and engaged in discussions with the protesters.[34] The movements in Egypt and Tunisia, like that in Israel, change the face of the situation in a part of the world that is probably the main focus of imperialist confrontations on the planet. As our article says, “The present international wave of revolts against capitalist austerity is opening the door to another solution altogether: the solidarity of all the exploited across religious or national divisions; class struggle in all countries with the ultimate goal of a world wide revolution which will be the negation of national borders and states. A year or two ago such a perspective would have seemed completely utopian to most. Today, increasing numbers are seeing global revolution as a realistic alternative to the collapsing order of global capital.”[35]

The three movements have contributed to the crystallization of a proletarian wing: in both Greece and Spain but also in Israel,[36] a "proletarian wing" is emerging, in search of self-organization, uncompromising struggle for class positions and a fight for the destruction of capitalism. The problems but equally the potentialities and the perspectives of this large minority cannot be addressed in the context of this article. What is certain is that this is a vital weapon that the proletariat has given life to in order to prepare its future battles.

C. Mir, 23-9-2011.

[1]. See en.internationalism.org/ir/146/editorial-protests-in-spain [3]. Given that this article analysed this experience in depth we will not repeat what we said here.

[2]. See our articles on these movements: en.internationalism.org/icconline/2011/08/social-protests-israel [4] and en.internationalism.org/icconline/2011/07/notes-on-popular-assemblies-greece [5].

[3]. “Communist revolution or the destruction of humanity”, Manifesto of the 9th ICC Congress, 1991.

[4]. International Review n°s. 103 and 104.

[5]. For discussion of this crucial concept of the decadence of capitalism, see amongst others https://en.internationalism.org/ir/146/great-depression [6].

[6]. “Why the proletariat has not yet overthrown capitalism”, International Review n° 103.

[7]. International Review n°104, op. cit.

[10]. “Since it has no economic basis within capitalism, its only real strength apart from its numbers and organisation, is its ability to become clearly aware of its nature, of its struggle’s ends and means” (International Review n° 103, op. cit.)

[11]. “Nationalisations, and a certain number of “social measures” (such as the state’s taking charge of the health system), were all completely capitalist measures. […] The capitalists had every interest in the good health of the workforce […] But these capitalist measures were presented as ‘workers’ victories’” (International Review n° 104, op. cit.).

[12]. We cannot deal here with why the working class is the revolutionary class of society and why its struggle represents the future for all other non-exploiting strata, a burning question as we have seen in the movement of the Indignants. The reader can find more material on this question in two articles published in International Review n°s. 73 and 74, “Who can change the world?: the proletariat is still the revolutionary class”.

[13]. See the “Theses on Decomposition”, https://en.internationalism.org/ir/107_decomposition [9].

[14]. See the articles that analysed this development of the class struggle in the International Review.

[15] See https://en.internationalism.org/ir/125_france_students [10] and https://en.internationalism.org/wr/295_vigo [11].

[16]. The bourgeoisie is careful to hide these events: the nihilist riots in November 2005 in France are much better known, including in the politicised milieu, than the conscious movement of students five months later.

[17]. Indignation is neither resignation nor hate. Faced with the insupportable dynamic of capitalism, resignation expresses passivity, a tendency to reject it without seeing how to confront it. Hate, on the other hand, expresses an active sentiment since rejection is turned into a struggle, but it is a blind struggle, without the perspective or reflection to elaborate an alternative, it is purely destructive, a collection of individual responses but without generating anything collective. Indignation expresses the active transformation of rejection with the effort to struggle consciously, seeking the development of a collective and constructive alternative.

[18] See “Resolution on the international situation”, International Review n° 130.

[19]. ICC online: “Israel protests: "Mubarak, Assad, Netanyahu! [4]".

[20]. ICC online: "Preliminary notes towards an account of the “Movement of popular assemblies” (TPTG, Greece) [5]".

[21]. Ibid.

[22]. “Israel protests...”, op. cit.

[23]. “Preliminary notes...”, op. cit.

[25]. See ¿Qué hay detrás de la campaña contra los violentos por los incidentes de Barcelona?, https://es.internationalism.org/node/3130 [12].

[26]. “Preliminary notes…”, op. cit.

[27]. Ibid.

[28]. Ibid.

[29]. Slogan of the Third International.

[30]. International Review n° 104, op. cit.

[32]. The "Plaza de Cataluña" was renamed “Tahrir Square” by the assembly, which not only showed an internationalist commitment but was also a slap in the face for Catalan nationalism, which considers this place as its crown jewel.

[33]. See “Israel protests…”, op. cit.: “A demonstrator interviewed on the RT news network was asked whether the protests had been inspired by events in Arab countries. He replied, “There is a lot of influence of what happened in Tahrir Square… There’s a lot of influence of course. That’s when people understand that they have the power, that they can organise by themselves, they don’t need any more the government to tell them what to do, they can start telling the government what they want”.

[34]. Ibid.

[35]. Ibid.

[36]. In this movement, “Some have openly warned of the danger that the government could provoke military clashes or even a new war to restore ‘national unity’ and split the protest movement” (ibid.), which at least implicitly reveals a distancing from the Israeli state of national unity in the service of the war economy and of war.

People:

- Indignados [14]

Recent and ongoing:

- social revolts [15]

Rubric:

Contribution to a history of the workers' movement in Africa (part 3): The 1920s & 30s

- 2256 reads

1923: “The Bordeaux Agreement” or “class collaboration” pact

It was in this year that that “the Bordeaux Agreement” was signed; a “treaty of friendship” between the colonial economic interests[1] and Blaise Diagne, the first African deputy to sit in the French National Assembly. Having drawn lessons from the magnificent insurrectionary strike in Dakar in May 1914 and its repercussions in subsequent years,[2] the French bourgeoisie had to reorganise its political apparatus to deal with the inexorable rise of the young proletariat in its African colony. It was in this context that it decided to use Blaise Diagne, making him “mediator/peacemaker” in conflicts between the classes, in fact a counter-revolutionary role. Indeed, the day after his election as deputy and having been a major witness to the insurrectionary movement against the colonial power, in which he himself had been involved at the beginning, Diagne was now faced with three options to play a historic role in future events: 1) to profit from the political weakening of the colonial bourgeoisie in the aftermath of the general strike, in which it suffered a defeat, by triggering a “national liberation struggle”; 2) to fight for the communist program by raising the banner of proletarian struggle inside the colony, profiting in particular from the success of the strike; 3) to bolster his own personal political interests by allying himself with the French bourgeoisie which at this time was holding out its hand to him.

Diagne eventually chose the last course, namely an alliance with the colonial power. In reality, the “Bordeaux Agreement” showed that the French bourgeoisie was not only afraid of working class militancy in its African colony, but was equally concerned by the international revolutionary situation.

“...Given the turn of events, the colonial government set about winning the black deputy’s support so that his powers of persuasion and his foolhardy courage could be used to serve the colonial power and its commercial interests. This way it would be able to pull the rug from under the feet of the African elite whose minds were running way with them when, at the time, the October Revolution (1917), the Pan-black movements and the threat of world communism were having a dangerously seductive affect in the colonies on the thinking of the colonised.

“[...] Such was the real meaning of the agreement signed in Bordeaux on June 12th, 1923. It marked the end of the combative and headstrong Diagnism and opened up a new era of collaboration between the colonisers and colonised, and left the deputy stripped of all his charisma that up to this point was his major political asset. A great impetus had been lost.”[3]

The first black member of the African colony remains faithful to French capital until his death

To better understand the meaning of this agreement between the colonial bourgeoisie and the young deputy, let’s retrace the path of the latter. Blaise Diagne was noticed very early on by the representatives of French capital, who saw him playing a future role in their political strategy and steered him in this direction. Indeed, Diagne had a strong influence on urban youth through the Young Senegalese Party that supported his campaign. With the support of youth, especially educated and intellectual youth, he entered the electoral arena in April 1914 and secured the single post of deputy with responsibility for the whole of French West Africa (FWA). Let’s recall that we were on the eve of massive imperialist slaughter and it was in these circumstances that the famous general strike broke out in May 1914 when, after mobilising the youth of Dakar with the prospect of mounting a formidable revolt, Diagne tried unsuccessfully to stop it, not wanting to jeopardise his interests as a young petit-bourgeois deputy.

In fact, once elected, he was responsible for ensuring the interests of big business on the one hand and enforcing the “laws of the Republic” on the other. Even before the Bordeaux Agreement was signed, Diagne had distinguished himself by successfully recruiting 72,000 “Senegalese Sharpshooters” for the global butchery of 1914-1918. It was for this reason that, in January 1918, he was appointed Commissioner of the Republic by the then French prime minister Georges Clemenceau. Given the reluctance of young people and their parents to be enrolled, he toured the African villages of FWA to persuade reluctant individuals and, by the use of propaganda and intimidation, managed to recruit tens of thousands of African young men to be sent off to their deaths.

He was also a strong advocate of that abominable “forced labour” in the French colonies, as indicated by his speech at the fourteenth session of the International Labour Office in Geneva[4].

All in all, the first black member of the African colony was never a real supporter of the workers’ cause; on the contrary, ultimately he was just a counter-revolutionary opportunist. Furthermore the working class would soon come to realise it: “...as if the Bordeaux Agreement had convinced the workers that the working class was now able to lead the march itself in the fight against economic injustice and for social and political equality, the trade union struggles were given, like a pendulum swing, an exceptional boost.”[5] Clearly, Diagne could not long keep the trust of the working class, and he remained faithful to his colonial sponsors until his death in 1934.

1925: a year of heightened militancy and solidarity faced with police repression

“The year of 1925 was shaken by three great social conflicts all of which had important consequences and all of which were indeed on the railways. First there was a strike of indigenous and European railwaymen in Dakar - Saint-Louis, from January 23rd to 27th, for economic demands; next, shortly afterwards, there was the threat of a general strike in Thies-Kayes, planned around specific demands including trade union rights; and finally, there was the workers' revolt in Bambara, on the railway construction site at Ginguinéo, a revolt where soldiers were called in to suppress it and refused to do so.”[6]

And yet the time was not particularly favourable for entering into struggle because to discourage working class militancy the colonial authorities had adopted a series of extremely repressive measures.

“During 1925, on the recommendations of the Governors General, particularly the one of FWA, some draconian measures were imposed by the Department for the Colonies specifically making revolutionary propaganda illegal.

“In Senegal, new instructions from the Federation (the two French colonies, FWA, FEA) had led to increased surveillance across the whole territory. And in each of the colonies of the group, a special service was established in conjunction with the General Security Service, to centralise in Dakar, and examine, all the evidence from the listening posts.

“[...] A new emigration regime with new arrangements for identifying natives was drawn up in the Ministry in December 1925. Every foreigner and every suspect had a file thereafter; the foreign press was under strict control, and it was commonplace for newspapers to be shut down [...] The mail was systematically violated, shipments of papersopened and often destroyed.”[7]

Once again, the colonial power trembled at the announcement of a new outbreak of working class struggle, hence its decision to establish a police state to take tight control of civil life and contain any social unrest arising in the colony, but also, and above all, to avoid contact between the workers in struggle in the colonies and their class brothers around the world; hence the draconian measures against “revolutionary propaganda”. And yet, in this context, important workers' struggles could violently erupt, despite all the repressive arsenal wielded by the colonial state.

A highly political railway strike

On January 24th 1925, European and African railway workers came out on strike together, establishing a strike committee and raising the following demands: “The employees of the Dakar - Saint-Louis railway unanimously agreed to halt the traffic on January 24th. They only took this action after much consideration and after feeling genuinely aggrieved. They had had no wage increase since 1921, despite the steady increase in the cost of living in the colony. Most of the Europeans were getting less than 1,000 francs in their monthly salary and a native got a daily wage of 5 francs. They were after higher wages to be able to live decent lives.”[8]

Indeed, the very next day, all employees in the various sectors of the railway left their machines, their workshops and offices, paralysing the railway for a short time. But this movement was above all highly political in nature in that it came right in the middle of a legislative campaign, forcing the parties and their candidates to take a clear position on the demands of the strikers. As a result, from that moment, the various politicians and commercial lobbies called on the colonial administration to get them back to work immediately by meeting the employees’ demands. And right away, on the second day of the strike, the railway workers’ demands were met in full. In fact, the members of the jubilant strike committee delayed their response until after consulting the rank and file. Similarly, the strikers insisted on having the order to return to work from their delegates in writing and sent by special train to all the stations.

“The workers had once again won an important victory in the struggle, showing great maturity and determination, along with adaptability and realism. [...] This success is all the more significant from the fact that all workers of the network, European and native, who had been at loggerheads over issues of colour and had problems working together, had wisely set aside their differences as soon as the threat of the draconian labour laws was on the horizon. [...] The governor himself could not help but notice the maturity and the unity and the timing of the strike’s organisation. The preparation, he wrote, had been very cleverly carried out. The mayor of Dakar himself, experienced and loved by the indigenous people, had not been notified of their participation. The timing of the deal was chosen so that commerce, to safeguard its own interests, supported the claims. The reasons given, with some justification, put the campaign in big trouble. In short, he concluded, everything came together for it to have its maximum effect and to give it the support of public opinion.” [9]

This is a vivid illustration of the high level of militancy and class-consciousness shown by the working class of the French colony, where European and African workers collectively took charge of organising their victorious struggle. Here we have a brilliant lesson in class solidarity consolidating gains from all previous experiences of confrontation with the bourgeoisie. And this makes even clearer the international character of the workers’ struggles at that time, despite the continual efforts of the bourgeoisie to “divide and rule”.

In February 1925, the strike of the telegraph office workers forces the authorities to back down after 24 hours

The movement of railwaymen had hardly finished when the telegraph office workers (‘câblistes’) went on strike, also raising many demands including a big wage increase and an improvement to their status. This movement came to an end after 24 hours for a good reason: “With the collaboration of the local and metropolitan powers, thanks to the successful intervention from members of the elected bodies, complete order returned within 24 hours, because satisfaction was given in a partial settlement to the câblistes, as conceded in the granting of an standby allowance to all staff.”[10]

So, buoyed by this success, the telegraph workers (European and indigenous together) put the rest of their demands on the table, threatening to go out on strike immediately. They took advantage of the strategic position they occupied as highly skilled technicians in the administrative and economic machinery who were clearly able to shut down communication networks across the territory. For their part, faced with the demands of the telegraph employees threatening a new strike, the bourgeoisie’s representatives decided to retaliate with a campaign of intimidation and accusation against the strikers: “How is it that the few functionaries who are agitating for an increase in pay can’t see they are digging their own grave?” [11]

In fact, political power and big business piled a great deal of pressure on the strikers, going as far as accusing them of trying to “deliberately destroy the economy” while also trying to undermine the their unity. With the pressure intensifying, the workers decided to resume work on the basis of demands met at the end of the previous strike.

This episode was also one of the high points in the struggle when the unity between the European and African workers was fully achieved.

Rebellion in the Thies-Kayes railway yards, December 11th 1925

A rebellion broke out on this line when a group of about a hundred workers decided to cross swords with their boss, a captain of the colonial army. A cynical and authoritarian figure, he was accustomed to being obeyed without question and inflicted physical harm on workers he deemed “lazy”.

“According to the investigation that had been carried out by the Administrator Aujas, commander of the Kaolack area, it appeared that a rebellion had broken out on December 11th because of “ill treatment” inflicted on these workers. The area commander added that, without admitting these statements entirely, captain Heurtematte acknowledged that he sometimes happened to hit a lazy and uncooperative labourer with a whip. [The incident] escalated after the captain had tied three Bambaras [an ethnic term], whom he took to be the main culprits, to stakes with ropes.”[12]

And things went wrong for the captain when he began to whip the three workers because their comrades in the yard decided to put an end to their torturer for good. He was only saved in the nick of time by the arrival on site of soldiers called to his aid. “The soldiers in question were French subjects from eastern Senegal and from Thies; having arrived there and heard what had happened, they unanimously refused the order to fire on the black workers. The poor captain said he had issued it as he feared for his life, assailed on all sides by a ferocious and menacing crowd.”[13]

This is quite remarkable because until now we were quite used to seeing the “sharpshooters” as submissive individuals, obediently accepting roles as “blacklegs” or outright “liquidators” of strikers. This gesture of fraternisation reminds us of other historical episodes where conscripts refused to use force against strikes or revolutions. The most famous example is of course the episode in the Russian Revolution where a large number of soldiers refused to fire on their revolutionary brothers, disobeying the orders from above despite the high risks involved.