2011 - 144 to 147

- 4251 reads

Index of International Reviews Published in 2011

International Review no.144 - 1st Quarter 2011

- 2509 reads

France, Britain, Tunisia: The future lies in the international development of the class struggle

- 2608 reads

The strikes and demonstrations of September, October and November in France, which took place following the reform of pensions, demonstrated a real fighting spirit in the ranks of the proletariat, even if they didn’t succeed in pushing back the attacks of the bourgeoisie.

This movement is taking place in the context of a renewed dynamic of our class as it gradually returns to the path of struggle internationally, following a course marked in 2009 and 2010 by the revolt of new generations of proletarians fighting poverty in Greece and by the determination of the Tekel workers in Turkey to extend their struggle against the sabotage of the unions.

Thus, students have mobilised in large numbers against the unemployment and job insecurity that capitalism has in store for them, as in Great Britain, Italy or the Netherlands. In the United States, despite being confined by the union straitjacket, several major strikes have broken out in various parts of the country since Spring 2010 in opposition to attacks: education workers in California, nurses in Philadelphia and Minneapolis-St-Louis, construction workers in Chicago, workers in the food industry in New York State, teachers in Illinois, workers at Boeing and in a Coca-Cola plant in Bellevue (Washington state), and dockers in New Jersey and Philadelphia.

At the time of going to press, in the Maghreb, and particularly in Tunisia, workers’ anger that has built up over decades spread like wildfire after 17th December when a young unemployed graduate set himself on fire in public after the fruit and vegetable stall that was his livelihood, was confiscated by the municipal police of Sidi Bouzid in the centre of Tunisia. Spontaneous demonstrations of solidarity spread throughout the country, where the population faces high unemployment and sharp increases in prices of basic foodstuffs. A fierce and brutal repression of this social movement led to dozens being killed, with police firing live ammunition at unarmed demonstrators. This only strengthened the outrage and resolve of the proletariat, firstly to demand work, bread and a little dignity and then the departure of President Ben Ali. “We are no longer afraid”, chanted the demonstrators in Tunisia. The children of proletarians took the lead and used the Internet or their mobile phones not only as weapons to broadcast and denounce the repression and to exchange information between themselves, but also to communicate with their family or friends outside the country, particularly in Europe, thus partially breaking the conspiracy of silence of all the bourgeoisies and their media. Everywhere our exploiters have tried to hide the class nature of this social movement, seeking to distort it by sometimes showing it to be like the riots that occurred in France in 2005 or as the work of vandals and looters, or sometimes presenting it as a “heroic and patriotic struggle of the Tunisian people” for “democracy” led by educated graduates and the “middle classes”.

The economic crisis and the bourgeoisie are striking blows all over the world. In Algeria, Jordan and China, similar social movements faced with sinking into poverty have been brutally repressed. This situation should push the more experienced proletarians of the central countries into seeing the impasse and bankruptcy into which the capitalist system is leading the whole of humanity, and into extending solidarity to their class brothers by developing their own struggles. And workers are indeed beginning to react gradually and are refusing to accept austerity, impoverishment and the “sacrifices” being imposed.

At present, this response clearly falls below the level of the attacks we are all being subjected to. That is undeniable. But there is a momentum under way and workers’ reflections and militancy will continue to grow. As proof we are again seeing minorities seeking to organise themselves, to actively contribute to the development of large-scale struggles and to escape the grip of the unions.

The mobilisation against pension reform in France

The social movement in France last autumn provides clear confirmation of the same dynamic as the previous movement that developed against the CPE.[1]

Millions of workers and employees from every sector routinely took to the streets of France. Alongside this, strikes broke out in various places from the beginning of September, some more radical than others, expressing a deep and growing discontent. This mobilisation is the first large-scale struggle in France since the crisis that shook the world financial system in 2007-2008. It is not only a response to pension reform itself but, in its scale and profundity, it is clearly a response to the violent attacks suffered in recent years. Behind this reform and other simultaneous or planned attacks, there is the growing refusal of all proletarians and other layers of the population to accept greater poverty, insecurity and destitution. And with the inexorable deepening of the economic crisis, these attacks are not about to stop. It is clear that this struggle foreshadows others to come, just as it follows closely on those that developed in Greece and Spain against drastic austerity measures there.

However, despite the massive response in France, the government did not give way. Instead, it was uncompromising, repeatedly affirming despite relentless pressure from the streets its firm intention to carry out this attack on pensions, quite cynically repeating the claim that this measure was “necessary” in the name of “solidarity” between the generations.

Why was this measure, which strikes at the heart of all our living and working conditions, passed at all? The whole population fully and strongly expressed its indignation and opposition to it. Why did this massive mobilisation fail to get the government to back down? It’s because the government was assured of the control of the situation by the unions, who have always accepted, along with the left parties, the principle of the “necessary reform” of pensions! We can compare this with the movement in 2006 against the CPE. This movement, which the media initially treated with the utmost contempt as a short-lived “student revolt”, eventually ended with the government forced to retreat faced with no other recourse than withdrawing the CPE.

Where is the difference? Primarily that the students had organised general assemblies (GAs) open to all without distinction of category or sector, public or private, employed or unemployed, casual workers, etc. This burst of confidence in the abilities of the working class and its power, and the profound solidarity inside the struggle, created a dynamic of extension in the movement giving it a massive scale involving all generations. Furthermore, while on the one hand wide-ranging debates and discussions took place in the general assemblies, not confined to the problems of students alone, on the other hand we saw a growing presence of workers on demonstrations alongside the college and high school students.

But it’s also because in their determination and spirit of openness, while leading sections of the working class towards open struggle, the students did not let themselves be intimidated by the manoeuvres of the unions.

Instead, while the latter, especially the CGT, tried to be at the head of the demonstrations to take control, the college and high-school students got in front of the union banners on several occasions to make clear that they did not want to be lost in the background of the movement they had launched. But above all, they affirmed their desire to keep control of the struggle themselves, along with the working class, and not let themselves be conned by the union leaderships.

In fact, one of the greatest concerns of the bourgeoisie was that the forms of organisation adopted by the students in struggle – sovereign general assemblies, electing co-ordinating committees and open to all, where the student unions often had a low profile – did not spread to employed workers if they should come out on strike. It is, moreover, no coincidence that during this movement, Thibault[2] repeatedly stated that workers could learn no lessons from the students on how to organise. So, while the latter have their general assemblies and coordinations, the workers themselves should have confidence in the unions. With no resolution in sight, and with the danger that the unions could lose control, the French government had to climb down because as the last bulwark of the bourgeoisie against the explosion of massive struggles, it was at risk of being demolished.

In the movement against pension reform, the unions, actively supported by the police and the media, sensing what lay ahead, took the measures necessary to be at the centre of things and made the appropriate preparations.

Moreover, the unions’ slogan was not “withdraw the attack on pensions” but “improve the reform”. They called for a fight for renewed negotiations between the unions and the state to make the reforms more “just”, more “humane”. Despite the apparent unity of the Intersyndicale (joint union body), we saw them exploit divisions from the start, clearly intending to reduce the “risks” of things getting out of control; at the beginning of the demonstrations the FO[3] union organised in its own corner, while the Intersyndicale, which organised the day of action on March 23, prepared to “tie up a deal” on reform following negotiations with the government, announcing two more days of action on May 26th and, above all, June 24th, the eve of the summer holidays. We know that a “day of action” at this time of year usually signals the final blow for the working class when it comes to implementing a major attack. However, the final day of action produced an unexpected turnout, with more than twice as many workers, unemployed, casual workers, etc., in the streets. And, while the first two days of action had been very downbeat, as highlighted by the press, anger and unrest were evident on the 24th June when the successful mobilisation boosted the morale of the proletariat. The idea that widespread struggle is possible gained ground. Evidently the unions also felt a change in the wind; they knew that the question of “how to struggle?” was running through people’s heads. So they decided to immediately take charge of the situation and to give a lead; there was no question for them of the workers beginning to think and act for themselves, and getting out of their control. They decided on a new day of action called for 7th September, after the summer holidays. And to be quite sure of holding back the process of reflection, they went as far as sponsoring flights over the beaches in the middle of the summer displaying publicity banners calling people to the demo on the 7th.

For their part, the left parties, which fully supported the pressing need to attack working class pensions, still came and joined in the mobilisation so they wouldn’t be completely discredited.

But another event, a news story, came out during the summer and fuelled workers’ anger: “The Woerth Case” (the politicians currently in office and the richest heiress of French capital, Ms. Bettencourt, boss of L’Oreal group, connived over tax evasion and all kinds of illegal dodges). Eric Woerth is none other than the minister in charge of pension reform. The sense of injustice was total: the working class must tighten its belt while the rich and powerful carry on with “their unseemly affairs”. So under the pressure of this open discontent and growing consciousness of the implications of this reform for our living conditions, the day of action on September 7th was announced, with the unions obliged on this occasion to espouse a belief in united action. Since then, not one union has failed to call for days of action that have brought together about three million workers on demonstrations on several occasions. Pension reform has become symbolic of the sharp deterioration in living standards.

But this unity of the “Intersyndicale” was a trap for the working class. It was intended to give the impression that the unions were committed to organising a broad offensive against the reform and were providing the means for this with repeated days of action in which they could see and hear their leaders ad-nauseum, arm in arm, churning out speeches on “sustaining” the movement and other lies. What frightened the unions most of all was the workers breaking from the union straitjacket and organising themselves. That is what Thibault, secretary general of the CGT, was trying to say when he “sent the government a message” in an interview with Le Monde on 10th September: “We can launch a blockade, with the possibility of a massive social crisis. It is possible. But it’s not us who are taking a risk”, and hegave the following example to better underline the high stakes facing the unions: “We’ve even found a small non-union firm where 40 out of 44 employees came out on strike. It’s a pointer. The more intransigent the government is, the more support for rolling strikes is going to grow.”

Clearly, when the unions aren’t there, the workers organise themselves and not only decide what they want to do but risk doing it massively. So to address this concern the big unions, particularly the CGT and SUD[4], have applied themselves with exemplary zeal: occupying the social stage and the media while with the same determination preventing any real expression of workers’ solidarity. In short, on the one hand a lot of hype, and on the other, action aimed at sterilising the movement with false choices, to create division, confusion, and better lead it to defeat.

Blockading the oil refineries is one of the most obvious examples of this. While the workers in this sector, whose fighting spirit was already very strong, were increasingly keen on showing their solidarity with the whole working class against the pension reform – workers moreover facing particularly drastic reductions in their own ranks - the CGT set about transforming this spirit of solidarity with a pre-emptive strike. Hence, the blockade of the refineries was never decided in real general assemblies where the workers could really express their views, but by union leaders, experts in manoeuvring who by stifling discussion adopted a sterilising action. Despite the strict confinement imposed by the unions, however, some workers in this sector did try to make contacts and links with workers in other sectors. But, being generally taken in by a strategy of “laying siege”, most of the refinery workers found themselves trapped by the union logic inside the factory, a real poison for broadening the struggle. Indeed, although the objective of the refinery workers was to strengthen the movement, to be a “strong arm” to make the government retreat, as it unfolded under union leadership the blockading of the depots was above all revealed to be a weapon of the bourgeoisie and its unions against the workers. Not only to isolate the refinery workers but also to make their strike unpopular, creating panic and raising the threat of widespread fuel shortages, the press generously spread its venom against these “hostage-takers, preventing people from going to work or going on holiday.” But the workers in this sector were also cut off physically; even though they wanted to offer their solidarity in the struggle, to create a balance of power to get the reforms withdrawn; this particular blockade has in fact been turned against them and the objective they originally set themselves.

There were many similar union actions, in certain sectors like transport, and preferably in areas with few workers, because at all costs the unions had to minimise the risk of extension and active solidarity. They had to pretend, to their audience, that they were orchestrating the most radical struggles and calling for union unity in the demonstrations, all the while sabotaging the situation.

Everywhere one could see the unions uniting in an “Intersyndicale” to better promote the semblance of unity, creating the appearance of general assemblies, without any real debate, confining topics to more corporatist issues, pretending in public to be fighting “for everyone” and “everyone together”... but with each sector organised in its own corner behind its small union boss, doing everything to prevent the creation of mass delegations that would seek solidarity with enterprises in the nearby area.

And the unions have not been alone in obstructing the possibility of such a mobilisation, because Sarkozy’s police, known for their alleged stupidity and anti-leftism, have provided the unions with indispensable support on several occasions through their provocations. Example: the events in Place Bellecour in Lyon, where the presence of a few “hooligans” (probably manipulated by the cops) was used as a pretext for a violent police crackdown against hundreds of young students, most of whom had only come to discuss with the workers at the end of a demonstration.

A movement full of potential

However, there have been no reports in the media of the many inter-professional committees or general assemblies (“AG interpros”) formed during this period; committees and assemblies whose stated aim was and is to organise outside the unions and to develop discussions completely open to all workers. These assemblies are the place where the working class can not only recognise itself, but above all where it can get massively involved.

This is what scares the bourgeoisie the most: that contacts are forming and growing extensively inside the working class, between young and old, between those in work, and those out of work.

We must draw the lessons from the failure of this movement.

The first observation is that it was the union apparatus that made the attack on the proletariat possible and that the failure of the movement is not at all something that was inevitable. The truth is that the unions did their dirty work and all the sociologists and other specialists, as well as the government and Sarkozy in person, saluted their “sense of responsibility”. Yes, without doubt, the bourgeoisie is fortunate to have “responsible” unions capable of breaking up a movement of this scale while being able at the same time to make everyone believe that they did everything possible to assist its development. Again it’s the same union apparatus that has succeeded in stifling and marginalising real expressions of autonomous struggle of the working class and of all workers.

However, this failure still bears much fruit because all the efforts made by all the bourgeoisie’s forces have not succeeded in inflicting a crushing defeat, as was the case in 2003 with the fight against the reform of public sector pensions when the country’s education sector workers had to make a bitter retreat after several weeks on strike.

Hence, this movement has led to the appearance in several places of a growth of minorities expressing a clear understanding of the real needs of the struggle for the whole proletariat: the need to take the struggle into its own hands to extend and strengthen it, showing that a profound reflection is taking place, that the development of the struggle is only just beginning, and demonstrating a willingness to learn from what has happened and to stay mobilised for the future.

As one of the leaflets of the “AG interpro” of the Gare de l’Est in Paris dated 6 November said: “We should have supported the sectors on strike at the start, not restricting ourselves to the single demand on pensions when redundancies, job cuts, the destruction of public services and low wages were being fought. This could have helped to bring other workers into struggle and extended and unified the strike movement. Only a mass strike which is organised locally and co-ordinated nationally through strike committees, inter-professional general assemblies, struggle committees, where we decide our demands and actions ourselves and we are in control, can have a chance of winning.”

“The power of workers lies not only in shutting down an oil depot or a factory, here or there. The power of workers lies in uniting at their workplaces, across occupations, plants, companies and categories and taking decisions together”, because“the attacks are just beginning. We have lost a battle, we have not lost the war. The bourgeoisie has declared class war on us and we still have the means of fighting it” (leaflet entitled “Nobody can struggle, take decisions and succeed on our behalf”, signed by the full-time and temporary workers of the “AG interpro” of the Gare de l’Est and Ile-de-France, cited above). We must defend ourselves by extending and developing our struggles massively and thus take control into our own hands.

This was made particularly clear with:

the real “AG interpros” that emerged in the struggle, albeit as small minorities and were determined to remain mobilised in preparing future combats;

the holding or attempted holding of street assemblies or people’s assemblies at the end of demonstrations, as happened particularly in Toulouse.

This willingness to take control of the struggle by some minorities shows that the class as a whole is beginning to question the unions’ strategy, without yet daring to draw all the consequences from its doubts and questionings. In all the GAs (whether union ones or not), most debates in their various forms have centred around essential questions about “How to struggle?”, “How to help other workers?”, “How to express solidarity?”, “Which other inter-professional GAs can we meet up with?”, “How do we combat isolation and reach out to as many workers as possible to discuss how to struggle together?” ... And in fact, a few dozen workers from all sectors, the unemployed, temporary workers and pensioners have regularly turned up each day in front of the gates of the 12 paralysed refineries, to “make up the numbers” facing the CRS riot police, to bring packed lunches for the strikers, to provide moral support.

This spirit of solidarity is an important element, revealing once again the profound nature of the working class.

“Having confidence in our own forces” must be the watchword for the future.

This struggle has the appearance of a defeat; the government did not back down. But in fact it constitutes a new step forward for our class. The minorities that emerged and tried to regroup, to discuss in the “AG interpros” or the people’s street assemblies, the minorities who have tried to take control of their struggles, totally distrusting the unions, reveal the questioning that is taking place in the heads of all the workers. This reflection will continue to develop and will eventually bear fruit. It is not a case of standing by, with arms folded, waiting for the ripe fruit to fall from the tree. All those who are conscious that the only thing the future holds is growing pauperisation and the need to fight the vile attacks of capital must help prepare the future struggles. We must continue to debate, to discuss, to draw the lessons of this movement and to spread them as widely as possible. Those who have begun to build relationships of trust and fraternity in this movement, on the marches and in the GAs, must try and continue their participation (in discussion circles, struggle committees, people’s assemblies or “public platforms”) because there are still questions that need answers, such as:

What role does the “economic blockade” have in the class struggle?

What is the difference between the violence of the state and that of struggling workers?

How do we respond to repression?

How do we take control of our struggles? How do we organise them?

What is the difference between a union GA and a sovereign GA? etc.

This movement is already rich in lessons for the world proletariat. In a different way, the student mobilisations that took place in Great Britain also provide evidence of the promise of the struggles that lie ahead.

Great Britain: the younger generation returns to the struggle

On Saturday October 23rd,following the announcement of the government austerity plan to drastically cut public spending, there were many demonstrations throughout the country called by various unions. The number of people that turned out (it was quite varied, with up to 15,000 in Belfast and 25,000 in Edinburgh) revealed the depth of anger. Another expression of widespread discontent was the student rebellion against university tuition fees being increased by 300%.

Young people are already left heavily in debt with astronomical sums to pay off (as much as £80,000!) after they graduate. Not surprisingly, these new increases provoked a whole series of demonstrations from the north of the country to the south (5 mobilisations in less than a month: 10th, 24th and 30th November and 4th and 9th December). This increase has all the same been passed into law by the House of Commons on December 8th.

The centres of struggle have been widespread: in further education, in high schools and colleges, the occupations of a long list of universities, numerous meetings on campus or in the street to discuss the way forward ... students received support and solidarity from many teachers, who closed their eyes to the absence of the protesters from their classes (attendance at classes is strictly monitored) or went along to discuss with their students. The strikes, demonstrations and occupations were anything but the tame events that unions and the left-wing “officials” usually try to organise. This spiralling spirit of resistance worried the government. A clear sign of its concern was the level of police repression at the demonstrations. Most gatherings ended in violent clashes with armed police adopting a strategy of “kettling” (confining demonstrators inside police cordons), backed up with physical attacks on demonstrators, which resulted in many injured and numerous arrests, mostly in London. Meanwhile occupations took place in fifteen universities with support from teachers. On November 10th, students stormed the headquarters of the Conservative Party and on December 8th, they tried to enter the Treasury building and the High Court, and demonstrators attacked the Rolls-Royce carrying Prince Charles and his wife Camilla. The students and their supporters attended the demonstrations in high spirits, with their own banners and slogans, with some of them participating in a protest movement for the first time. Spontaneous walkouts, the taking of Conservative Party HQ at Millbank, the defiance or creative avoidance of police lines, the invasion of town halls and other public spaces are just some of the expressions of this openly rebellious attitude. The students were sickened and outraged by the attitude of Aaron Porter, president of the NUS (national union of students) who condemned the occupation of the Conservative Party headquarters, attributing it to the violence of a small minority. On 24th November in London, thousands of demonstrators were “kettled” by the police within minutes of setting off from Trafalgar Square, and despite some attempts to break through police lines, the forces of order detained thousands of them for hours in the cold. At one point, the mounted police rode directly at the crowd. In Manchester, at Lewisham Town Hall in south London, and elsewhere, we have seen similar scenes of brute force. The newspapers are playing their usual role as well, printing photographs of alleged “wreckers” after Millbank, running scare stories about revolutionary groups targeting the nation’s youth with their evil propaganda. All this shows the real nature of the “democracy” we live under.

The student revolt in the UK is the best answer to the idea that the working class in the UK remains passive faced with a torrent of attacks by the government on every aspect of our living standards: jobs, wages, health, unemployment, disability benefits as well as education.

A whole new generation of the exploited class does not accept the logic of sacrifice and austerity that the bourgeoisie and its unions are imposing. It’s only by taking control of its struggles, developing its solidarity and international unity that the working class, especially in the most industrialised, “democratic” countries, will be able to offer society a real future. It’s only by refusing to shoulder the burden of a bankrupt capitalism all over the world that the exploited class can put an end to the misery and terror of the exploiting class by overthrowing capitalism and building a new society based on satisfying the needs of the whole of humanity and not on profit and exploitation.

W 14/01/11

[1]. Read the article in International Review n° 125,“Theses on the Spring 2006 student movement in France". [2]

[2]. General Secretary of the CGT, the main body of affiliated trade unions in France and associated with the French Communist Party.

[3]. FO: "Force ouvrière". This union came out of a split with the CGT in 1947 at the start of the Cold War and was supported and financed by the American unions of the AFL-CIO. Up until the 1990s, this organisation was known for its "moderation" but thereafter it adopted a more "radical" stance by trying to "outflank" the CGT on the left.

[4]. SUD: "Solidaires Unitaires Démocratiques". Small union on the far left of the spectrum of the forces that supervise the working class, and largely influenced by leftist groups.

Recent and ongoing:

Capitalism has no way out of its crisis

- 3409 reads

The weakest of the super-indebted national economies must be rescued before they go bankrupt and ruin their creditors; austerity plans designed to contain the debt only aggravate the risk of recession and a cascade of bankruptcies; attempts at recovery by printing money merely re-launch inflation. There is an impasse at the economic level and the bourgeoisie is incapable of proposing policies with the slightest coherence.

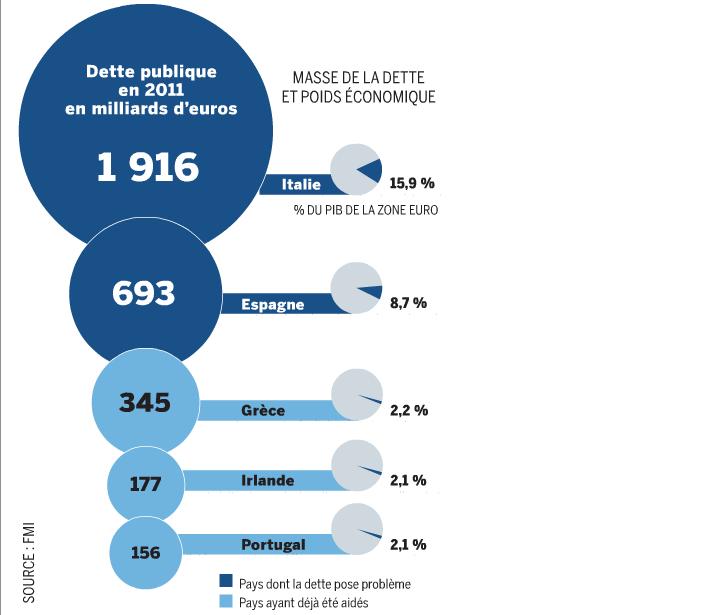

The “rescue” of European economies

At the very moment that Ireland negotiated its rescue plan, the International Monetary Fund admitted that Greece would not be able to fulfill the plan that they and the European Union devised in April 2010. Greece’s debt would have to be restructured, even if they didn’t use this word. According to D. Strauss Khan, the boss of the IMF, Greece must be allowed to repay its debt not in 2015 but in 2024. That is, on the 12th of Never, given the course of the present crisis in Europe. Here is a perfect symbol of the fragility of some if not most European countries undermined by debt.

Of course this concession to Greece must be accompanied by supplementary measures of austerity. After the austerity plan of April 2010 - which was financed by the non-payment of pensions for two months, the lowering of indemnities in the public sector, and price rises resulting from an increase in taxes on electricity, petrol, alcohol, tobacco, etc - there are also plans to cut public employment.

A comparable scenario unfolded in Ireland where the workers were presented with a fourth austerity plan. In 2009 public sector wages were lowered between 5 and 15%, welfare payments were suppressed and retired workers were not replaced. The new austerity plan negotiated with the rescue plan included the lowering of the minimum wage by 11.5%, the lowering of welfare payments, the loss of 24,750 state jobs and the increase in sales tax from 21 to 23%. And, as in Greece, it is clear that a country of 4.5million people, whose GNP in 2009 was 164 billion euros, will not be able to pay back a loan of 85 billion euros. For these two countries, these violent austerity plans presage future measures that will force the working class and the major part of the population into unbearable poverty.

The incapacity of new countries (Portugal, Spain, etc) to pay their debts is shown in their attempt to avoid the consequences by adopting draconian austerity measures and preparing for worse, as in Greece and Ireland.

What are the austerity plans trying to save?

A reasonable question since the answer is not obvious. One thing is certain: their aim is not to alleviate the poverty of the millions who are the first to suffer the consequences. A clue lies in the anxiety of the political and financial authorities about the risk that more countries would in turn default on their public debt. More than a risk since nobody can see how this scenario will not come to pass.

At the origin of the bankruptcy of the Greek state is a considerable budget deficit due to an exorbitant mass of public spending (armaments in particular) that the fiscal resources of the country, weakened by the aggravation of the crisis in 2008, cannot finance. As for the Irish state, its banking system had accumulated a debt of 1,432 billion euros (on a GDP of 164 billion euros) which the worsening of the crisis had made impossible to reimburse. As a consequence, the banking system had to be largely nationalised and the debt was transferred to the state. Having paid a relatively small amount of these debts of the banking system the Irish state found itself in 2010 with a public deficit corresponding to 32% of GDP! Beyond the fantastic character of such figures, we can see that whatever the different histories of these two national economies, the result is the same. In both cases, faced with an insane level of indebtedness of the state or of private institutions, it is the state which must assume the integrity of the national capital by showing its capacity to reimburse the debt and pay the interest on it.

The inability of the Greek and Irish economies to repay their debt contains a danger that extends way beyond the borders of these two countries. And it is this aspect which explains the panic at the top levels of the world bourgeoisie. In the same way that the Irish banks were supported by credit from a series of world states, the banks of the major developed countries held the colossal debts of the Greek and Irish states. There are different opinions concerning the level of the claims of the major world banks on the Irish state. Let’s take the “average”: “According to the economic daily Les Echos de Lundi, French banks have a 21.1 billion euro exposure to Ireland, behind the German banks (46 billion), British (42.3 billion) and American (24.6billion).”[1] And concerning the exposure of the banks by the situation in Greece: “The French institutions are the most exposed with 55 billion euros in assets. The Swiss banks have invested 46 billion, the Germans 31 billion”.[2] The non-bailout of Greece and Ireland would have put the creditor banks in a very difficult situation, and thus the states on which they depend. It would have been even more the case for countries in a critical financial situation (like Spain and Portugal) that are also exposed in Greece and Ireland and for whom such a situation would have proved fatal.

That’s not all. The non-bailout of Greece and Ireland would have signified that the financial authorities of the EU and the IMF would not guarantee the finances of countries in difficulty. This would have led to a stampede of creditors away from these countries and the guaranteed bankruptcy of the weakest of them, the collapse of the euro and a financial storm that would make the failure of Lehman Brothers in 2008 look like a mild sea breeze. In other words, the financial authorities of the EU and the IMF came to the rescue of Greece and Ireland not to save these two states, still less the populations of these two countries, but to avoid the meltdown of the world financial system.

In reality, it is not only Greece, Ireland and a few other countries in the South of Europe whose financial situation has deteriorated. “.. the following figures show the level of total debt as a percentage of GDP [January 2010]: 470% for the UK and Japan, gold medals for total indebtedness; 360% for Spain; 320% for France, Italy and Switzerland; 300% for the US and 280% for Germany.”[3] In fact, all countries, whether inside or outside the Euro zone, are indebted beyond their ability to repay. Nevertheless the Euro zone countries have the supplementary difficulty that its states are unable to create the monetary means to “finance” their deficits. This is the exclusive preserve of the European Central Bank. Other countries like the UK and the US, equally indebted, do not have this problem since they have the authority to create their own money.

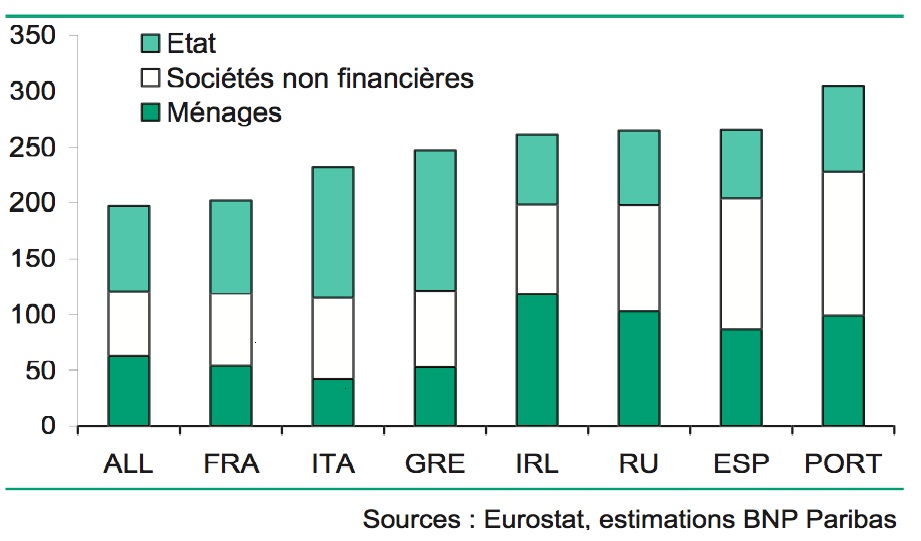

Public and private debt in 2009 excluding financial institutions (% of the GDP)[4]

The levels of indebtedness of all these states show that their commitments exceed their ability to pay to an absurd degree. Calculations have been made which show that Greece needs a budget surplus of at least 16 or 17% to stabilise its public debt. In fact these are all countries that are indebted to a point where their national production doesn’t permit the repayment of their debt. In other words the states and private institutions hold debt that can never be honoured.[5] The table above, which shows the debt of each European country (outside of financial institutions, contrary to the figures mentioned above) gives a good idea of the immensity of the debts contracted as well as the fragility of the most indebted countries.

Given that the rescue plans have no chance of success, what else is their significance?

Capitalism can survive only thanks to plans of permanent economic support

The Greek rescue plan cost 110 billion euros and Ireland’s 85 billion. These massive financial contributions from the IMF, the Euro zone and the UK (which gave 8.5billion euros when Cameron’s government was making its own austerity plan to reduce public expenses by 25% in 2015[6]) are only money issued against the wealth of the different states. In other words the money extended to the rescue plan is not based on newly created wealth but is nothing but the result of printing money, Monopoly money.

Such support to the financial sector, which finances the real economy, is in fact a support to real economic activity. Thus on the one hand draconian austerity plans are put in place, announcing still more draconian austerity plans, and on the other, threatened by the collapse of the financial system and the blockage of the world economy, plans of support are adopted whose content is very similar to what are known as “recovery plans”.

In fact the US is going furthest in this direction: Quantitative Easing nº2, creating 900 billion dollars,[7] has no other meaning than the attempt to save the American financial system whose ledgers are full of bad debts, and to support the anaemic economic growth of the US, which cannot overcome its sizeable budget deficit.

Having the advantage that the dollar is the money of world exchange the US does not suffer the same constraints as Greece, Ireland and other European countries. That’s why, as many think, a Quantitative Easing nº3 cannot be ruled out.

Thus the support of economic activity by budgetary measures is much stronger in the US than in the European countries. But that does not stop the US from trying to drastically slash its budget deficit, as illustrated by Obama’s proposal to block the wages of federal employees. In fact one finds in every country in the world such contradictions revealed in the policies adopted.

The bourgeoisie has exceeded the limits of indebtedness that capitalism can sustain

We thus have plans of austerity and plans of recovery at the same time! What is the reason for such contradictions?

As Marx showed, capitalism suffers genetically from a lack of outlets because the exploitation of labour power necessarily leads to the creation of a value greater than the outlay in wages, because the working class consumes much less than it produces. Up until the end of the 19th century, the bourgeoisie had to offset this problem by the colonisation of non-capitalist areas where it forced the population, with various means, to buy the merchandise produced by its capital. The crises and wars of the 20th century illustrate that this way of answering overproduction, inherent to capitalist exploitation, was reaching its limits. In other words, non-capitalist areas of the planet were no longer sufficient for the bourgeoisie to realise the surplus product that was needed for enlarged accumulation. The deregulation of the economy at the end of the 1960s, manifested in monetary crises and recessions, signified the quasi-absence of the extra capitalist markets as a means of absorbing the surplus capitalist production. The only solution henceforth has been the creation of an artificial market inflated by debt. It has allowed the bourgeoisie to sell to states, households and businesses without the latter having the real means to buy.

We have often shown that capitalism has used debt as a palliative to the crisis of overproduction that has ensnared it since the end of the 1960s. But we should not confuse debt with magic. Actually debt must be progressively repaid and the interest paid systematically, otherwise the creditor will not only stop lending but risk bankruptcy himself.

Now the situation of a growing number of European countries shows that they can no long pay the part of the debt demanded by their creditors. In other words these countries must reduce their debt, in particular by cutting expenses, when 40 years of crisis have shown that the increase of the latter was an absolutely necessary condition to avoid a world recession. All states, to a greater or lesser degree are faced with the same insoluble contradiction.

The financial storms shaking Europe at the moment are thus the product of the fundamental contradictions of capitalism and illustrate the absolute impasse of this mode of production.

We will now deal with other characteristics of the present situation.

Developing inflation

At the very moment when most countries have austerity plans that reduce internal demand, including for basic necessities, the price of agricultural raw materials has sharply increased. More than 100% for cotton in a year;[8] more than 20% for wheat and maize between July 2009 and July 2010[9] and 16% for rice between April-June 2010 and the end of October 2010.[10] Metals and oil went in a similar direction. Of course, climatic factors have a role in the evolution of the price of food products, but the increase is so general that other causes must be at play. All countries are preoccupied by the level of inflation that is increasing in their economies. Some examples from the “emerging countries”:

- officially inflation in China reached an annual rate of 5.1% in November 2010 (in fact every specialist agrees that the real figures for inflation in this country is between 8 and 10%);

- in India inflation reached 8.6% in October;

- in Russia it was 8.5% in 2010.[11]

The development of inflation is not an exotic phenomenon reserved for the emerging countries. The developed countries are more and more concerned: a 3.3% rate in November in the UK was seen as worrying by the government; 1.9% in virtuous Germany caused disquiet because it occurs alongside rapid growth.

What then, is the cause of this return of inflation?

Inflation is not always the result of vendors raising their prices because demand exceeds supply and therefore carries no risk of losing sales. Another factor entirely can cause this phenomenon. The increase in the money supply over the past three decades for example. The printing of money, that is the issuing of new money when the wealth of the national economy does not increase in the same proportion, leads inevitably to a depreciation of the money in circulation and thus to an increase in prices. Now, all the official statistics show that since 2008 there has been a strong increase in the money supply in the great economic zones of the planet.

This increase encourages the development of speculation with disastrous consequences for the working class. Given that demand is too weak as a result of the stagnation or lowering of wages, businesses cannot raise their market prices without losing sales. These same businesses or investors turn away from productive activity which is not profitable enough or too risky, and use the money created by the central banks for speculation. Concretely that means buying financial products, raw materials or currencies with the hope that that they can be resold with a substantial profit. Consumer products become tradable assets. The problem is that a good part of these products, in particular agricultural products, are also commodities consumed by vast numbers of workers, peasants, unemployed, etc. Consequently, as well as a lowering of income, a great part of the world population is hit by the rise in the price of rice, bread, clothes, etc.

Thus the crisis, which obliges the bourgeoisie to save its banks by means of the creation of money, leads the workers to suffer two attacks:

- the lowering of their wages;

- the increase in the price of basic commodities.

Prices of basic necessities have been rising since the beginning of the century for these reasons. From the same causes today, the same effects. In 2007 – 2008 (just before the financial crisis) great masses of the world population were forced into hunger riots. The consequences of the present price explosion have immediately led to the revolts in Tunisia, Egypt and Algeria.

The level of inflation won’t stop rising. According to Cercle Finance from 7th December, the rate of 10 year T bonds[12] has increased from 2.94% to 3.17% and the rate of 30 year T bonds has increased from 4.25% to 4.425%. That clearly shows that the capitalists anticipate a loss of the value of the money they invest and thus demand a higher rate of return on it.

The tensions between national capitals

During the Depression of the 1930s, protectionism and trade war developed to such an extent that one could speak of a “regionalisation” of exchange. Each of the great industrialised countries reserved a zone for its domination which allowed it to find a minimum of outlets. Contrary to the pious intentions published by the recent G20 in Seoul, according to which the different participants declared a voluntary ban on protectionism, reality is quite different. Protectionist tendencies are clearly at work today behind the euphemism of “economic patriotism”. It would be too tedious to list all the protectionist measures adopted by different countries. Let us simply mention that the US in September 2010 was taking 245 anti-dumping measures; that Mexico from March 2009 had taken 89 measures of commercial retaliation against the US and that China recently decided to drastically limit the export of its “rare earths” needed for a lot of high technology products.

But, in the present period, it’s currency war that will be the major manifestation of trade war. We have already seen that Quantitative Easing Nº2 was a necessity for American capital. At the same time, to the extent that the creation of money can only lead to the lowering of its value, and thus the price of Made in USA products on the world market (relative to the products of other countries) QE is a particularly aggressive protectionist measure. The under-valuation of the Chinese yuan has similar objectives.

However, despite the trade war, the different countries have agreed to prevent Greece and Ireland from defaulting on their debt. The bourgeoisie is obliged to take very contradictory measures, dictated by the total impasse of its system.

What solutions can the bourgeoisie propose?

Why, in the catastrophic situation of the world economy do we find articles like those of the Tribune or Le Monde entitled “Why growth will come”[13] or “The US wants to believe in the economic recovery”?[14] Such headlines, which are only propaganda, are trying to send us to sleep, and above all make us think that the bourgeoisie’s economic and political authorities still have a certain mastery of the situation. In fact the bourgeoisie only has the choice between two policies, rather like the choice between the plague and cholera:

- either it proceeds by creating money as it has done with Greece and Ireland, since all the funds of the EU and the IMF come from the printing of money by its various member countries. But then it heads towards a devaluation of currencies and an inflationist tendency that can only get worse;

- or it tries a particularly draconian austerity in order to stabilise the debt. This is the German solution for the Euro zone, since the major part of the cost of support for countries in difficulty is borne by German capital. The end result of such a policy can only be the rapid fall into depression, as indicated by the fall of production that we have seen in 2010 in Greece, Ireland and in Spain following the adoption of austerity plans.

Recently published texts by a number of economists propose their solutions to the present impasse. But they are either pure propaganda to make us think that capitalism, despite everything, has a future, or an exercise in self-hypnosis. To take one example, according to Professor M Aglietta[15] the austerity plans adopted in Europe are going to cost 1% of growth in European Union which will be about 1% in 2011. His alternative solution reveals that the greatest economists have nothing realistic to offer: he was not afraid to say that a new “regulation” based on the “green economy” would be the solution. He only “forgot” one thing: such a “regulation” implies considerable expense and thus an even more gigantic creation of money than at present, when the bourgeoisie is particularly worried about the resumption of inflation.

The only true solution to the capitalist impasse will emerge from the more and more numerous, massive and conscious struggles of the working class against the economic attacks of the bourgeoisie. It will lead naturally to the overthrow of this system whose principle contradiction is that of the production for profit and accumulation and not the satisfaction of human needs.

Vitaz 2/1/11

[3]. Bernard Marois, professor emeritus at HEC: www.abcbourse.com/analyses/chroniquel-economie_shadock_analyse_des_dette... [7]

[4]. Key to abbreviations: Etat = country; Societies non financieres = non-financial companies; Menages = Households

[5]. J. Sapir “Can the Euro survive the crisis?” Marianne, 31 December 2010.

[6]. But it is revealing that Cameron is beginning to fear the depressive effect of the plan on the British economy.

[7]. QE2 had been fixed at $600billion but the FED was obliged to renew the purchase of matured debt at $35billion a month.

[8]. Blog-oscar.com/2010/11/las-flambee-du-cours-du-coton (the figures on this site date from the beginning of November. Today they have been largely surpassed).

[9]. C. Chevré, MoneyWeek, 17 November 2010

[10]. Observatoire du riz de Madagascar; iarivo.cirad.fr/doc/dr/hoRIZon391.pdf

[11]. Le Figaro,16 Decembre 2010, www.lefigaro.fr/flash-eco/2010/1216/97002-20101216FILWWW00522-russie-l-i... [8]

[12]. American Treasury Bonds

[13]. La Tribune 17 December 2010

[14]. Le Monde 30th December 2010

[15]. In the broadcast “L’éspirit public” on “France Culture” radio, 26 December 2010

Recent and ongoing:

- Economic Crisis [9]

The economic crisis in Britain

- 4640 reads

The text that follows is, apart from a few minor changes, the economic part of the report on the situation in Britain for the 19th Congress of the ICC’s section in Britain. We thought it would be useful to publish it to the outside since it provides a number of factors and analyses which enable us to grasp how the world economic crisis is expressing itself in the world’s oldest capitalist power.

The international context

In 2010 the bourgeoisie announced the end of the recession and predicted that the world economy would grow over the next two years led by the emerging economies. However, there are serious uncertainties about the global situation, reflected in differing projections of growth. The IMF in its World Economic Outlook Update of July 2010 predicted global growth of 4.5% this year and 4.25% next. The World Bank in its Global Economic Prospects report for summer 2010 envisaged growth of 3.3% this year and next and 3.5% in 2012 if things go well but of 3.1% this year, 2.9% next and 3.2% in 2012 if things do not go well. The concern is particularly centred on Europe where the World Bank’s higher estimate is dependent on “Assuming that measures in place prevent today’s market nervousness from slowing the normalization of bank-lending, and that a default or restructuring of European sovereign debt is avoided”.[1] The lower growth rate if this is not achieved will affect Europe particularly, with predicted growth rates of 2.1, 1.9 and 2.2 percent between 2010 and 2012.

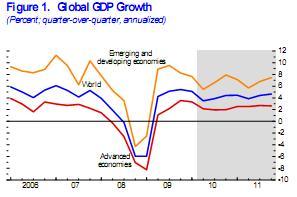

Source: IMF World Economic Outlook Update, July 2010

The situation remains fragile with concern about high levels of debt and low levels of bank lending and the possibility of further financial shocks, such as that in May this year that saw global stock markets lose between 8 and 17% of their value. The scale of the bailout is itself one of the causes of concern: “the size of the EU/IMF rescue package (close to $1 trillion); the magnitude of the initial market reaction to the possibility of a Greek default and eventual contagion; and continued volatility, are indications of the fragility of the financial situation…a further episode of market uncertainty could entail serious consequences for growth in both high-income and developing countries.”[2] The prescription of the IMF, as one might expect, is to reduce state spending, with the inevitable result that the working class will face austerity: “high-income countries will need to cut government spending (or raise revenues) by 8.8 percent of GDP for a 20 year period in order to bring debt levels down to 60 percent of GDP by 2030.”

For all their appearance of objectivity and sober analysis, these recent reports by the IMF and World Bank suggest there is a depth of uncertainty and fear within the ruling class about its ability to overcome the crisis. The possibility of other countries following Ireland back into recession remains real.

The evolution of the economic situation in Britain

This section draws on official data to give an overview of the course of the recession and the response from the government. However, it is important to begin by recalling that the crisis began within the financial sector, stemming from the crisis in the US housing market and encompassing the major banks and financial bodies around the globe that had become involved in lending where there was a real risk of the loans not being paid back. This was at its most extreme in the sub-prime mortgage market in the US, the contagion from which spread through the financial system because of the trading that developed based on the financial instruments derived from these loans. However, other countries, notably Britain and Ireland, had contrived to produce their own housing bubbles that contributed, together with a massive rise in unsecured personal borrowing, to create a level of debt that in Britain ultimately exceeded the country’s annual GDP. The crisis that developed flowed across into the ‘real’ economy leading to recession. The whole situation evoked a very forceful response from the British ruling class that poured unprecedented sums of money into the financial system and cut interest rates to a historic low.

Official figures show that Britain went into recession in the second quarter of 2008 and came out in the fourth quarter of 2009 with a peak to trough fall of 6.4% of GDP.[3] This figure, which was recently revised downwards, makes this recession the worst since the Second World War (the recessions of the early 1990s and 1980s saw falls of 2.5% and 5.9% respectively). Growth in the second quarter of 2010 was 1.2%, increasing significantly from the 0.4% of the fourth quarter 2009 and 0.3% of the first quarter 2010. However, it is still 4.7% below the pre-recession level as can be seen in the graph above.

The manufacturing sector has been the most affected by the recession, registering a peak to trough decline of 13.8% between the fourth quarter in 2007 and the third quarter of 2009. Since then manufacturing has expanded by 1.1% in the last quarter of 2009 and by 1.4% and 1.6% in the two quarters since.

The construction industry showed a sharp rebound in growth of 6.6% in the second quarter of 2010, contributing 0.4% to the overall growth rate for that quarter. However, this follows very substantial declines in both house building (down 37.2% between 2007 and 2009) and commercial and industrial work (down 33.9% between 2008 and 2009).

The service sector recorded a peak to trough fall of 4.6% with business and financial services falling by 7.6% “much stronger than in earlier downturns, making the largest single contribution to the fall”.[4] In the last quarter of that year it returned to growth of 0.5% but in the first quarter of 2010 this fell to 0.3%. Although the decline in this sector was less than in others, its dominant position in the economy meant that it was the largest contributor to the overall decline in GDP during this recession. The decline in the service sector was also greater in this recession than those of the early 1980s and early 1990s where the falls were 2.4% and 1% respectively. More recently, the business services and finance sector has shown stronger growth and contributed 0.4 percentage points to the overall GDP figure.

As might be expected both exports and imports declined during the recession. This was most marked in the trade in goods (although the balance actually improved slightly): “In 2009 the deficit fell by £11.2 billion to £81.9 billion. There was a record fall in exports of 9.7 per cent – from a record £252.1 billion to £227.5 billion. However, this was accompanied by a fall in imports of 10.4 per cent, the largest year-on-year fall since 1952, which had a much larger impact since total imports are significantly larger than total exports. Imports fell from a record £345.2 billion in 2008 to £309.4 billion in 2009. These large falls in both exports and imports were a result of a general contraction of global trade associated with the worldwide financial crisis which began late in 2008.”[5] The decline in services was smaller, with imports falling by 5.4% and exports by 6.9% with the balance, which remained positive, going from £55.4bn in 2008 to £49.9bn in 2009. The total trade in services in 2009 was £159.1bn in exports and £109.2bn in imports, which is significantly less than that of the trade in goods.

Between 2008/9 and 2009/10 the current account deficit doubled from 3.5% of GDP to 7.08%. The Public Sector Net Borrowing Requirement, which includes borrowing for capital spending, went from 2.35% of GDP in 2007/8, to 6.04% in 2008/9 and 10.25% in 2009/10. In 2008 it was £61.3bn and in 2009 £140.5bn. Total government net debt was calculated to be £926.9bn in July this year or 56.1% of GDP, compared to £865.5bn in 2009 and £634.4bn in 2007. In May 2009 Standard and Poor raised the possibility of downgrading Britain’s debt status from the highest triple A rating, which would have led to significant increases in borrowing costs.

The number of companies going bankrupt increased during the recession, rising from 12,507 in 2007 (which was one of the lower figures for the decade) to 15,535 in 2008 and 19,077 in 2009. The number of acquisitions and mergers rose during the second half of the decade to reach 869 in 2007 before falling over the next two years to 558 and 286 respectively. Figures for the first quarter of 2010 do not suggest any increase is taking place. This suggests that while there has been destruction of the capital associated with the businesses going insolvent this has not yet led to a general process of consolidation as might be expected coming out of a crisis, which itself may indicate that the real crisis remains with us.

During the crisis the pound fell sharply against a number of other currencies, losing over a quarter of its value between 2007 and the start of 2009, prompting the Bank of England to comment “The fall of more than a quarter since mid-2007 is the sharpest over a comparable period since the breakdown of the Bretton Woods agreement in the early 1970s”[6] There has been a recovery since but the pound remains about 20% below its 2007 exchange rate.

House prices fell sharply after the bursting of the property bubble and although they began to rise again this year they remained substantially below their peak and in September fell again by 3.6%. The number of sales remains at a historic low.

The stock market suffered sharp falls from mid 2007 and, although it has recovered since then, there is still uncertainty. The concerns about the debts of Greece and other countries prior to the intervention of the EU and IMF led to a significant fall in May this year as the graph below shows.

Source: The Guardian

Inflation rose to nearly 5% in September 2008 before falling to below 2% a year later. It has since risen to over 3% during 2010, above the Bank of England's target of 2%.

Unemployment is estimated to have increased by about 900,000 during the recession, which is considerably less than in previous recessions. In July 2010 the official figures were 7.8% of the workforce totalling some 2.47 million people.

State intervention

The British government intervened robustly to limit the crisis, initiating a range of policies that were taken up by many other countries. Gordon Brown basked in this glory for a few months, famously stating that he had saved the world in a slip of the tongue during a debate in the House of Commons. There were a number of strands to the state’s intervention:

- cuts in the Bank of England base interest rate. Between December 2007 and March 2009 the rate was progressively cut from 5.5% to 0.5%, bringing it down to the lowest rate on record and below the rate of inflation;

- intervention to directly support the banks, leading to nationalisation or part nationalisation. This started with Northern Rock in February 2008 and was followed by Bradford and Bingley. In September the government brokered the take-over of HBOS by Lloyds TSB. In October £50bn was made available to the banks for recapitalisation. In November 2009 a further £37bn investment resulted in the de-facto nationalisation of RBS/Nat West and the partial nationalisation of Lloyds TSB/HBOS;

- quantitative easing, also known as the asset purchase facility. In March 2009 plans to inject £75bn over three months were announced. This was gradually increased and at present the total stands at £200bn. The Bank of England explains that the purpose of quantitative easing is to put more money into the economy to keep the rate of inflation at its target of 2% and this became necessary when further reductions of the base rate were no longer possible after it had been reduced to 0.5%. This is achieved by the bank purchasing assets (mainly gilts) from private sector institutions and crediting the sellers’ account, effectively creating new money. This sounds simple, but according to the Financial Times “No one is sure whether or how quantitative easing and other unorthodox monetary policies works”[7]

- intervention to encourage consumption. In January 2009 VAT was cut from 17.5% to 15% and in May 2009 the car scrappage scheme was introduced. The increase in the guarantee on bank deposits to £50,000 in October 2008 can be seen as part of this since its aim was to reassure consumers that their money would not just disappear in the event of a bank collapse.

The result was the containment of the immediate crisis with no further bank collapses. The price was a substantial increase in debt as noted above. Official figures give the cost of government intervention as £99.8bn in 2007, £121.5bn in 2009 and £113.2bn in July this year. These figures do not include the cost of purchasing assets such as the stakes in the banks or the expenditure on quantitative easing (which would add another £250bn or so to the total) on the grounds that these assets will only be held temporally by government before being sold back. Whether this is so remains to be seen, although Lloyds TSB has paid back some of the money it received.

The interventions have also been partly credited for the lower than expected rise in employment during the recession. This will be dealt with in more detail below.

However, the longer-term prospects seem more questionable:

- interventions to manage inflation and theoretically encourage spending have not brought the headline rate to target, although it is suggested that the underlying trends are lower than the headline rate suggests. However, the cost of food is rising globally so may affect the rate over time, particularly as it affects those who are less well off;

- the efforts to inject liquidity into the system, by reducing the cost of borrowing and increasing the supply of money, have not produced the increase in lending that was hoped for, leading to repeated calls from politicians for the banks to do more;

- the impact of the VAT cut and car scrappage scheme contributed to the initial recovery at the end of 2009 but have now ended. There was a slight fall in car sales in the first quarter of 2010 but the car scrappage scheme was still in place then. Overall, there have been reductions in most areas of household consumption, growth in personal debt has begun to reduce and the rate of savings has increased. Given the central role played by debt-funded household consumption in the boom this clearly has implications for any recovery.

The consensus forecasts for GDP growth in 2010 and 2011 in Britain are 1.5% and 2.0% respectively. This is above the 0.9% and 1.7% predicted for the Euro Area but below the 1.9% and 2.5% forecast for the OECD as a whole[8] and below the forecasts for Europe from the IMF quoted at the start of this report.

However, to grasp the real significance of the crisis it is necessary to penetrate below these surface phenomena to examine aspects of the structure and functioning of the British economy.

Historical and structural issues

Changes within the composition of the British economy: from production to services

Source: Economic and Labour Market Review

The rise of the financial sector

The weight of the banking sector within the economy can be gauged by comparing its assets to the total GDP for the country. This can be seen in the chart above. By 2006 British banks’ assets were over 500% of national GDP. In the US assets rose from 20% to 100% of GDP over the same period, thus the weight of the banking sector in Britain is proportionately far greater. However, its capital ratio (this is the capital held by the bank in comparison to that lent) did not keep pace, falling from 15-25% at the start of the 20th century to about 5% at the end. This increased sharply over the last decade and just before the crash leverage of the major global banks was about 50 times equity. This underlines that the global economy has been built on a tower of fictitious capital over the last few decades. The crisis of 2007 threatened to topple the whole edifice and this could have been catastrophic for Britain given its reliance on this sector. This is why the British bourgeoisie had to respond as it did.

The nature of the service sector

Conclusion

What hope for an economic recovery?

The global context

The options for British capitalism

The impact of the crisis on the working class

Perspectives

Life of the ICC:

- Congress Reports [11]

General and theoretical questions:

- Economic crisis [12]

The Hungarian Revolution of 1919 (ii): The example of Russia 1917 inspires the workers in Hungary

- 4073 reads

The example of Russia 1917 inspired the workers in Hungary

In the previous article in this series,[1] we saw how the Social Democratic party, the main rampart of capitalism, carried out a despicable manoeuvre in order to deal with the developing workers' struggle. This manoeuvre aimed at making the communists appear to be responsible for a mysterious attack perpetrated against the editorial board of the Social Democratic paper Népszava. The intention was to criminalise them and so unleash a wave of repression, initially against the communists but then going on to annihilate the new-born workers' councils and destroy any revolutionary spirit in the Hungarian proletariat.

In this second article we will see how this manoeuvre failed and how the revolutionary situation continued to mature so that the Social Democratic party tried another manoeuvre, which was risky but which in the end was a success for capitalism: to ally with the Communist Party, “take power” and organise “the dictatorship of the proletariat”. This blocked the dynamic of rising struggles and the development of proletarian self-organisation and led the revolution into an impasse that resulted in its utter defeat.

March 1919: the crisis of the bourgeois republic

The truth about the attack on the newspaper soon came out. The workers felt that they had been tricked and their indignation grew even more when the torture inflicted upon the communists came to light. The credibility of the Social Democratic party was seriously damaged and this increased the popularity of the Communists. Struggles around specific demands grew in number from the end of February: the peasants seized the land without waiting for the eternal promise of “agrarian reform”,[2] more and more workers flocked to the Budapest workers' council and tumultuous discussions led to bitter criticism of the Social Democratic and union leaders. The bourgeois republic, that had created so many illusions in October 1918, was now a disappointment. The 25,000 soldiers who had been sent home from the front were shut up in their barracks and organised themselves into councils; during the first week of March, not only did the assemblies in the barracks re-elect their representatives – with a significant increase in the number of Communist delegates – they also passed motions stating that, “government orders will not be obeyed unless formerly ratified by the Budapest soldiers' council”.

On 7th March, an extraordinary session of the workers' council of Budapest adopted a resolution which, “demanded the socialisation of all the means of production and that they be placed under the direction of the councils”. Although socialisation without first destroying the bourgeois state apparatus is bound to be a limping measure, this declaration nevertheless expressed the enormous self-confidence of the councils and was a response to two urgent questions: 1) the bosses' sabotage of production, which was completely disorganised by the war effort; 2) the tragic lack of foodstuffs and of goods to satisfy basic needs.

Events took a radical turn. The metal workers' council presented the government with an ultimatum; it gave it five days to hand over power to the proletarian parties.[3] On 19th March, there took place the biggest demonstration seen up to then, which was called by the workers' council of Budapest; the unemployed demanded an allowance and a ration card, as well as the abolition of rents. On 20th, the typographers went on strike; this became generalised from the following day and made two demands: the liberation of the Communist leaders and a “workers' government”.

Although this demonstrates that there was a maturation towards a revolutionary situation, it also shows that the political level was still far below what was necessary for the proletariat to take power. In order to take power and keep it, the proletariat must be able to count on two indispensable factors: the workers' councils and the communist party. In March 1919 the workers' councils in Hungary had just taken their first steps, they had just begun to feel their power and autonomy and they were still trying to free themselves from the stifling control of Social Democracy and the unions. Their two main weaknesses were:

- their illusions in the possibility of a “workers' government” which would unite the Social Democrats and the Communists. As we will see, this was to be the death knell of a revolutionary development of the situation;

- they were still organised according to economic sectors: councils of metal workers, of typographers, of textile workers, etc. In Russia, from 1905 onwards, the councils were organised horizontally, regrouping the workers as a whole across divisions of sector, region, nationality, etc; in Hungary there existed both councils based on sector and also horizontal councils within towns, which meant that there was a risk of corporatism and dispersion.

In the first article in this series, we stressed that the Communist Party was still very weak and heterogeneous, that the debate had only just begun to develop within it. It was weakened by the absence of a solid international structure to guide it – the Communist International had only just celebrated its first congress. For these reasons, as we will see, it had enormous weaknesses and an absence of clarity that was to make it an easy victim of the trap that Social Democracy laid for it.

The merger with the Social Democratic party and the proclamation of the Soviet Republic

Colonel Vix, the representative of the Entente,[4] issued an ultimatum, which stipulated that there be created a demilitarised zone within Hungarian territory, to be governed directly by allied command. It was to be 200 kilometres wide, which meant that it would occupy a third of the country.

The bourgeoisie never confronts the proletariat openly. History teaches us that it tries to trap it between two fronts, the left and the right. Here we see the right opening fire with the threat of military occupation; this was to be concretised from April onwards with a full-blown invasion. For its part, the left went into action immediately afterwards with a pathetic declaration by President Karolyi: “Our homeland is in danger. The most serious moment in our history is upon us. (...) The time has come for the Hungarian working class to use its force - the only organised force in the country - and its international relations to save its homeland from anarchy and dismemberment. I therefore propose that a Social Democratic government be formed that will confront the imperialists. The stakes of this struggle are the fate of our country. In order to wage such a struggle it is indispensable that the working class recover its unity and that the agitation and disorder brought about by the extremists, cease. With this in mind, the Social Democrats must find common ground for an agreement with the Communists”.[5]

This crossfire in which the working class was caught up; the right with its military occupation, and the left with the appeal for national defence, converged on the same aim: to save capitalist domination. The military occupation – the worst affront that can be inflicted on a nation state – was really intended to crush the revolutionary tendencies of the Hungarian proletariat. In addition, it enabled the left to drive the workers towards the defence of the fatherland. This kind of trap had been used before; in Russia in October 1917, when the Russian bourgeoisie realised that it was unable to crush the proletariat, it preferred to let German troops occupy Petrograd; at the time the working class parried this manoeuvre well by embarking on the seizure of power. The right-wing Social Democrat Garami revealed the strategy that was to follow in the wake of Count Karolyi's appeal: “entrust the government to the Communists, await the total failure that will be theirs and then, and only then, when rid of these dregs of society, can we form an homogenous government”.[6] The centrist wing of the party[7] adopted the following policy: “As Hungary has essentially been sacrificed by the Entente, which has obviously decided to annihilate the revolution, it would seem that the only tools that the latter has at its disposal are Soviet Russia and the Red Army. To win the support of the latter, the Hungarian working class must essentially wield power and Hungary must become a real popular and soviet republic.” adding that “in order to ensure that the Communists do not abuse this power, it would be better to wield it with them!”[8]

The left wing of the Social Democratic party defended a proletarian position and tended to evolve towards the Communists. Garami's right-wingers and Garbai's centrists manoeuvred cleverly against them. Garami resigned from all of his responsibilities. The right wing agreed to be sacrificed in favour of the centrist wing which, “declaring its agreement with the communist programme” positioned itself to seduce the left.[9]

Following this U-turn, the new centrist leadership proposed the immediate merger with the Communist Party and nothing less than the seizure of power! A delegation of the Social Democratic Party went to meet Bela Kun in prison and made the proposal to unite the two parties, to form a “workers' party”, to exclude all “bourgeois parties” and to form an alliance with Russia. The talks took place in the space of one day, at the end of which Bela Kun draw up a six-point statement which, among other things, underlines, “The directive committees of the Hungarian Social Democratic party and of the Hungarian Communist Party have decided in favour of the total and immediate unification of their respective organisations. The name of the new organisation is to be Unified Socialist Party of Hungary (PSUH). (...) The PSUH will immediately take power in the name of the dictatorship of the proletariat. This dictatorship is to be exercised by the councils of workers, peasants and soldiers. There will be no more National Assembly (...). A military and political alliance will be concluded with Russia as completely as is possible.”[10]

President Karolyi, who followed these negotiations closely, handed in his resignation and made a declaration addressed “to the world proletariat to obtain help and justice. I resign and hand over power to the proletariat of the Hungarian people.”[11]