International Review no. 26 - 3rd Quarter 1981

- 2855 reads

Counter-resolution on the class struggle

- 1957 reads

The proletarian struggle in Poland has marked a new and decisive step forward in the continuing process of mass strike which began with the struggles at Denain and Longwy, reemerged in the dockers' strike at Rotterdam and in the British steel strike, and which posed in differing degrees in each struggle the need for the self-organization, extension and generalization of the struggle.

1) These struggles have confirmed the new characteristics of proletarian struggle in decadence. Although they are a response to the aggravation of the economic crisis, they cannot aim at a real improvement in the workers' living and working conditions. In addition to the economic demands that form the basis for these struggles to start from, they prefigure and prepare the future revolutionary assault on the state, the only historic response open to the working class in face of the generalized crisis of capitalism.

In these struggles the real antagonism existing between the needs and practice of the working class and all the false strategies and conceptions of unionism could be seen. All these unionist-style strategies have been the reply of the bourgeoisie to the working class in struggle. They have all attempted to undermine the self-organization of the working class and the dynamic toward generalization contained in its struggles. As well as that, the methods of trade unionism derail the development of political consciousness within the working class, a consciousness that has been emerging in this period.

2) In future, the only way for the proletariat to go forward will increasingly be for it to go beyond corporatism, localism, and nationalism by setting up in its struggles general assemblies and elected and revocable strike committees, and by deepening the political antagonisms between all the bourgeois factions acting inside the class and inside the organized proletariat.

3) The other fundamental aspect of the present struggles is that they act as a historical brake against the tendency towards war contained in the blind contradictions of the decadent capitalist system in crisis. For the first time in history, today's period is one in which the proletariat has been able to impose on the bourgeoisie its own initiative in the class struggle. Unlike the 1930s when the economic crisis accentuated the defeat suffered by the working class in the 1920s, throughout the 1970s it was possible to see the slow and chaotic reconstitution of the strength of the working class. This new upsurge of proletarian struggle has prevented the bourgeoisie from leading society toward another world war. The inability of the bourgeoisie to take this road rests on the fact that those parties most capable of mobilizing the proletariat for a new massacre are the leftist parties, but they are precisely the parties which the new upsurge in working class struggle has brought into question.

4) Faced with a proletariat which is regaining its class strength once more, the Left has seen its margin of maneuver reduced, and its capacity to mystify the class , which it had accumulated during the years of counter-revolution, has been reduced as well. During these last ten years a crisis has developed within these parties: they've been wracked by splits and a real erosion of their militant base. The appearance of new leftist groups corresponds to the bourgeoisie's need to adapt to the struggles of the working class, but at the same time such a dispersal shows the potentially real weaknesses of the Left in future.

5) Such an erosion of the Stalinist and Social Democratic counter-revolutionary machines has repercussions on the whole political apparatus of the bourgeoisie. The Stalinist and Social Democratic machines are an integral part of the state and they share all the characteristics of the decadent bourgeoisie -- its senility and its incapacity to become a homogeneous bloc when faced with its historical enemy, the working class. In fact, it is the state itself which has been weakened by the blows delivered by the workers' struggle. But weakness doesn't mean outright collapse. Each bourgeois party, using its own methods and its specific arsenal of anti-working class measures, tries to prevent the outright collapse of the state. The bourgeoisie is threatened by working class struggle, but it is also forced to adopt stringent austerity measures to avoid the utter economic bankruptcy of its system. Caught in this contradiction it tries, where it can, to react and respond to the struggle of the working class by bringing forward a whole series of tactics essentially based on democratic mystifications and illusions. The other aspect of the bourgeoisie's tactics is its necessity to find a way of breaking the struggles from the inside, either by openly sabotaging them or by politically derailing them.

6) Today the activity of the Left parties is right at the centre of the problem confronting the bourgeoisie. How is it to defeat the proletariat and make it accept austerity and later on the war? But, in reality, in the period to come, an increasing instability will become evident in bourgeois politics because the Left parties are going to be forced to develop more and more incoherent political orientations in the face of the working class:

-- in opposition they risk losing their influence because they cannot present themselves eternally as defenders of the immediate interests of the working class. Because of that, they risk losing their capacity to sabotage struggles from within.

-- in power, they quickly lose their credibility in the eyes of the working class by organizing and managing austerity. Today, workers forget less and less easily what the Left has done when it is in power.

7) In the years ahead, we will see the ripening of a generalized political crisis within the bourgeoisie. But, contrary to those years in which the proletariat was not able to use such a crisis for its own ends, we are now entering a period when it is going to become crucial for the working class to take advantage of the crisis of the bourgeoisie. In this sense, the political character of the struggles that have just happened will become more and more explicit and pose in clearer terms the importance of the role and intervention of revolutionary groups. Given the need for revolutionaries to understand how the working class is to achieve a unification of its struggle, the ability of revolutionaries to analyze the contradictions wracking the bourgeoisie as a whole and tearing apart each of the individual national bourgeoisies, will be decisive in the ripening of class consciousness.

CH.

The proposed counter-resolution was: retain points 1, 2 and 7 of the Resolution on class struggle and replace the rest with the counter-resolution.

Life of the ICC:

Generalized economic crisis and inter-imperialist conflicts

- 9317 reads

The course of the economic crisis

In the report on the ‘Crisis and Inter-Imperialist Conflicts’ adopted at the Third Congress of the ICC in 1979, we pointed out that all the palliatives with which world capital had tried to bring about a recovery from the slump of 1974-75 (the third and sharpest downturn since the onset of the open crisis of overproduction in 1967) had failed. The excess industrial capacity and slackening rate of investment in new plant throughout the advanced countries of the American bloc, the virtual bankruptcy of the backward societies in the Western orbit, and the failure of the various Five-Year Plans to achieve their goals throughout the Russian bloc, led us to conclude that world capitalism stood on “...the brink of another decline in industrial production, investment and trade -- stronger than the downturns of 1971 and 1974 -- as the 1980s begin”. (International Review no.18, p. 8)

In the third volume of Capital, Karl Marx lays bare the link between the fall in the rate of profit and the saturation of the market[1]. The economic crisis of capitalism, whether in its cyclical form in the ascendant phase or in the form of an historic crisis (which poses the alternative, inter-imperialist world war or proletarian revolution) which characterizes the decadent phase, explodes in three inter-connected manifestations according to Marx: overproduction of commodities, overproduction of capital and overproduction of labor power. We can best gauge the extent to which our forecast of 1979 that capitalism “…stands poised on the brink of new and even more devastating economic cataclysms” (International Review no.18,p.3), has been confirmed by first tracing the course of the economic crisis on these three levels in the industrial behemoths of the West, which dominate the world economy.

The West

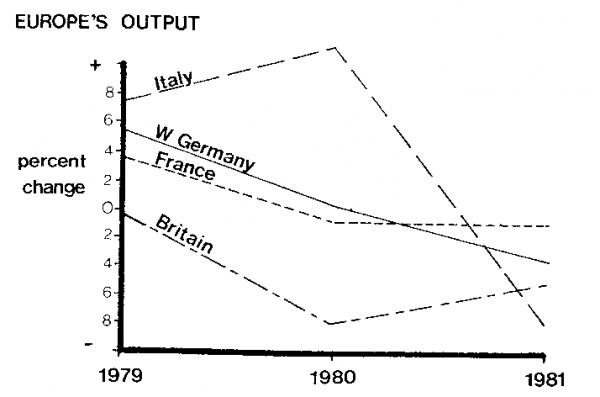

The slowdown in the growth of industrial production[2] which characterized the EEC, Japan and the US in 1979 has now given way to a sharp decline in industrial output in the EEC:

The catastrophic nature of this collapse of industrial production can best be seen in Britain where manufacturing output has fallen 15 percent since 1979 and now stands at its lowest level since 1967; the extent of overproduction in key industries can be found in the fact that under the EEC’s mandatory production controls for steel, production of that basic commodity will be 20 per cent lower by April 1981 than it was in 1979; while production of automobiles will fall 10 to 12 per cent this year, as Japanese companies compensate for the saturation of the world market by renewed dumping in Europe. In West Germany, the mighty engineering sector which was the key to that country’s trade surplus over the past several years has now followed the steel and auto producers along the path of falling output.

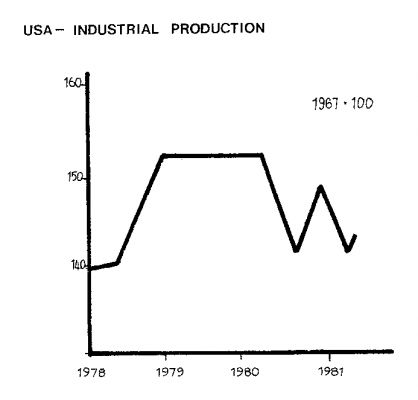

In the US, stagnation in industrial production during 1979 gave way to an abrupt drop in 1980; and the mild upturn at the end of last year was quickly transformed into a new downturn -- a “double-dip” recession, which presages the only kind of “recovery” that capitalism can generate today:

The magnitude of the decline in output in key industries in the US can be seen in the fact that in February 1981 the production of steel and lumber (the basis of the housing industry) was only at the same level as in 1967, while automobile production was even lower than it had been in 1967.

Japan alone among the industrial giants of the American bloc has so far escaped this slump in manufacturing output[3]. But Japan's industries are so completely dependent on exports that domestic demand is incapable of providing any significant compensation for the shocks which the looming protectionism of its major trading partners and/or a downturn in world trade will bring.

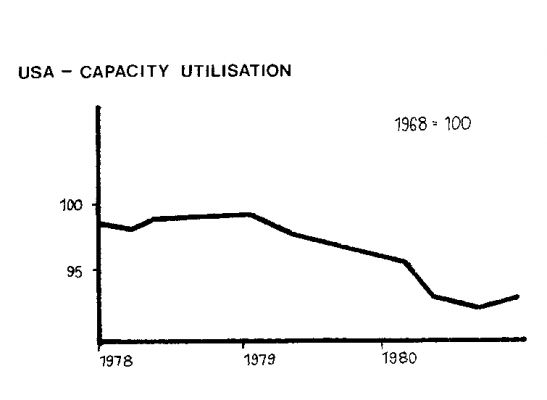

The enormous overproduction of commodities which has produced this downturn in industrial production has in its wake already brought about a strong fall in investment in capital goods and the beginnings of a collapse of manufacturing profits. In 1981 real spending on plant and equipment is expected to fall 2-3 per cent in West Germany, 7 per cent in Italy and10.25 per cent in Britain. In the US, as the utilization of manufacturing capacity has declined, investment in new plant has fallen below the level necessary to maintain America’s industrial base at competitive levels:

Meanwhile, the more than four billion dollars lost by American automakers in 1980 is certainly the most spectacular harbinger of the general collapse of profits which this overproduction of commodities must result in.

The barrier of a saturated world market, the lack of effective demand relative to the hyper-developed productive capacity of world capitalism means that at the level of global capital any effort to counteract the decline in the rate of profit by new investments to raise the productivity of labor can only exacerbate the difficulty of realizing the mass of surplus value by adding to the plethora of unsaleable commodities. Therefore, as industrial output falls, a growing mass of unemployed capital thirsting for profit is frantically hurled into the activity of speculation. It is possible that the overproduction of capital has already thrown one trillion dollars into speculation. It is this veritable flood of unemployed capital seeking a profitable short-term placement that has kept oil prices rising despite a 6 per cent fall in demand in the American bloc during 1980. The feverish excitement in the gold markets in the face of a decline in the demand for industrial gold has led specialists in precious metals to estimate that “50 percent of demand is now speculatively oriented” (New York Times, International Economic Survey, 8 February 1981). The fiasco of the Hunt brothers’ efforts to corner the silver market, the heavy trading in currency futures and foreign exchange by the world’s leading corporations and financial institutions, all attest to the frantic search for short-term profits on the part of idle capital. Indeed, today the very price of the world’s major currencies is increasingly determined by the rise and fall of interest rates -- the fluctuations ions of which can send billions of dollars scurrying from one country to another almost overnight. This vast overproduction of capital has spawned an enormous speculative bubble which threatens to burst with catastrophic consequences for world capital.

As industrial production slumped during 1980-81, unemployment rose at an accelerated rate throughout the industrialized countries of the American bloc:

Unemployment rates

| March 1979 | March 1980 | March 1981 |

France | 6.1% | 6.6% | 7.5% |

W. Germany | 4.1% | 3.5% | 4.6% |

Holland | 5.1% | 5.0% | 8.1% |

Italy | 8.0% | 8.2% | 8.6% |

Japan | 2.1% | 1.9% | 2.1% |

Sweden | 2.1% | 2.2% | 2.5% |

USA | 5.7% | 6.0% | 7.3% |

Britain | 5.6% | 5.7% | 9.6% |

The real dimensions of this “excess population” (Marx), which is one of the most vicious manifestations of the economic crisis of capitalism, can be seen in the OECD’s prediction that by mid 1981 there will be 23 million officially unemployed workers in the industrialized countries of the American bloc. In Holland, there is now more unemployment than at any time since the end of World War II. In Britain, there will be more than three million jobless workers by mid 1981 -- a higher figure than that reached even in the depths of the depression in the 1930s. In West Germany, economists at the Commerzbank not only predict a rise of unemployment for an official figure of 4.8 per cent, but also forecast that the number of short-time workers will rise from 130,000 to 520,000 this year. The racist attacks on immigrant workers in France (orchestrated by the government and the left in opposition alike), the plans of giant firms, like Italy’s FIAT (announced layoffs of 24,000 workers) and France’s Rhone-Poulenc (a projected 25 per cent cut in its workforce), to further slash their labor force, are so many signs of the grim fate that capital is planning for millions more workers in the 1980s.

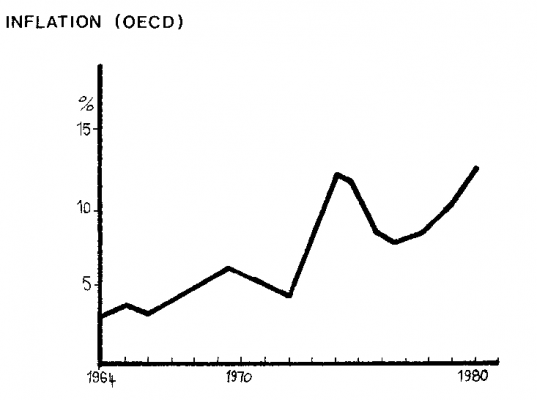

To these devastating manifestations of the open crisis of overproduction (overproduction of commodities, capital and labor-power) must be added another manifestation, no less ominous for capital: galloping inflation in the very midst of a collapse of production and profits. Capitalism, caught in the grip of a permanent crisis, has reacted by using the drug of inflation (creation of money and credit) in a desperate effort to compensate for the lack of effective demand brought about by the definitive saturation of the world market. This continuous and deliberate bloating of the money supply has now so swollen the costs of production that it has dragged down an already rapidly falling rate of profit and accelerated the very breakdown in production it was originally intended to prevent. Moreover, while in the other downturns in production since the onset of the open crisis -- 1967, 1971, 1974-1975 -- the rate of inflation fell, in the present downturn it has leaped ever higher.

The underdeveloped countries

In the backward Asian, African and Latin American countries which provide vital materials and necessary markets for the American bloc, the past two years have seen ranks of the impoverished peasantry and inhabitants of the miserable shanty towns swell. Today, according to the World Bank -- one of the institutions by which American three continents -- 800 million underfed human beings subsist in conditions of ‘absolute poverty’. Apart from a few oil-producing countries, the flow of dollars to whom provides a market for Western arms manufacturers or winds up on deposit in Western banks, the countries of the ‘third world’ have been reduced, by mounting trade and balance of payments deficits and a skyrocketing burden of foreign debt, to virtual bankruptcy. An absolute dependence on imported food -- the grim product of the chronic agricultural crisis capitalism has provoked -- has meant that these countries’ overall payments deficits have risen from $12 billion in 1973 to an anticipated $82 billion in 1981. Meanwhile, constant borrowing from Western private and public financial institutions, largely to cover these deficits, has resulted in an astronomical foreign debt of 290 billion dollars for these starving countries as a whole.

Over the past two years, a string of countries beginning with Zaire, Jamaica and Peru, continuing with Turkey, and most recently including Sudan and Bolivia, have tottered on the brink of bankruptcy and had to request a rescheduling of their debts from their imperialist creditors. In each of these cases, the only alternative to default and an immediate end to imports has been to accept some form of de facto control by the IMF -- the primary instrument of American imperialism’s domination of the backward countries of its bloc -- is a quid pro quo for the necessary debt rescheduling. This control has usually taken three complementary forms:

1. Devaluation of the debtor countries’ currency, which means that for the same amount of their own money its creditors can appropriate a much greater volume of raw materials.

2. Higher food prices in order to restrict imports, which means an even greater harvest of starvation in the “third world”.

3. Wage freezes so as to extract even more surplus value from the laboring population with which to pay back the interest and principal on the enormous debt.

With an inflation rate of 7per cent to 15 per cent and a budget deficit last year of $11 billion dollars, China too has followed the path of so many other backward countries of the American bloc to the IMF hot in hand. In her first year as a member of the IMF (which completed her economic integration into the American bloc) China has borrowed nearly $1.5 billion. Moreover, confirming our 1979 forecast that China would not fulfill the hopes of Western businessmen for a vast market in which to dispose of their overproduction, China has already this year cancelled or “deferred” capital investments contracted with western firms worth $3.5 billion. The 13 per cent cut in state spending announced in February indicates that the Peking regime has now officially embarked on the same path of draconian austerity as the rest of the capitalist world.

THE Russian bloc

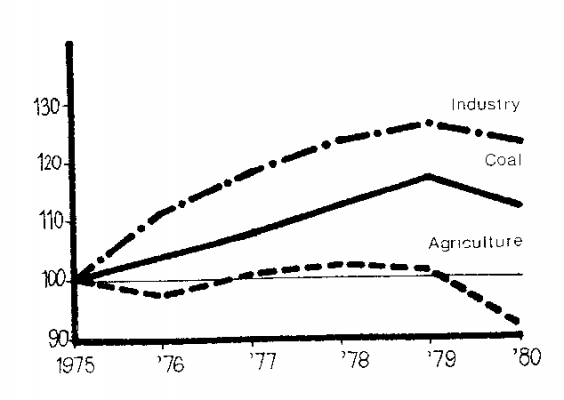

1n our 1979 report on the “Crisis and Inter-Imperialist Conflicts” we showed how one of the most important manifestations of the world economic crisis in the Russian bloc was a chronic scarcity of capital. During the 1970s, the Russian bloc prevented the downturn in production to which this scarcity of capital would have condemned it, by massive loans from Western banks and governments. This flow of money capital to the East (which financed the imports of Western capital goods and technology) allowed the economies of the Russian bloc to continue growing -- albeit at a much slower rate than before the onset of the open crisis of world overproduction. The example of Poland illustrates how economic activity was maintained in the face of a saturated world market and a scarcity of capital. In1971, Poland’s foreign debt was a miniscule $800 million; in 1980 (just before the outbreak of the mass strike in August) it had grown to a staggering $23.5 billion. However, by 1979, the greater part of the new loans were necessary just to assure the interest and repayment of principal on old loans, rather than to expand production. As a result, the Polish economy -- before the mass strike -- had begun to collapse:

Poland’s economic collapse differs only in its sharpness from the economic downturn in which the whole of the Russian bloc is now mired. Thus, in Russia agricultural production declined 3 per cent in 1980 and production in key industrial sectors like coal, steel, nuclear reactors and electric power fell far short of the goals set in the last Five-Year Plan.

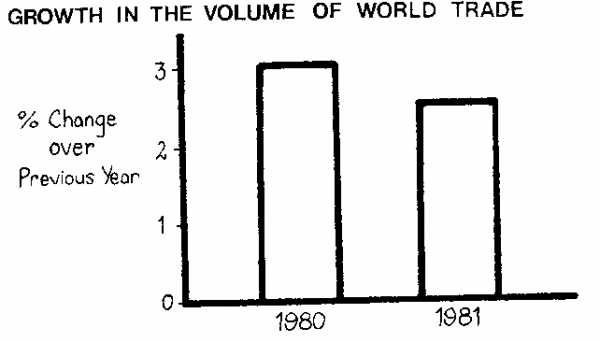

World trade

The economic slump which has now simultaneously hit all sectors of world capital ‑- both the advanced and backward countries of the American bloc and the whole of the Russian bloc -- has led to a continued and ever faster decline in the rate of growth of world trade:

A brief description of the ways in which world capital sought to ‘recover’ from slump of 1974-75 and the failure of that effort, is necessary to demonstrate why world trade is today virtually stagnant. Two basic economic stratagems were used to create a temporary pick-up in economic activity. First, the US became the ‘locomotive’ of the world economy by artificially providing a market for the rest of its bloc through enormous trade deficits. Between 1976-1980 the US bought commodities overseas to a value of 100 billion dollars more than it sold. Only the US -- because the dollar is the world’s reserve currency -- could run up such a trade deficit without the necessity for a massive devaluation of its currency. Second, the US flooded the world with dollars in an unprecedented credit expansion in the form of loans to the backward countries and to the Russian bloc (this latter largely by way of financial institutions based in Europe). This mass of paper values temporarily created an effective demand which allowed world trade to pick up. The virtual bankruptcy of the backward countries of the American bloc, which has driven country after country to avoid default by putting itself under the fiscal dictatorship of the IMF and submit itself to its austerity plans, has already removed one of the crutches which has propped up world trade over the past several years. A drastic reduction in imports by these countries -- necessary if a train of bankruptcies and a possibly mortal blow to the international monetary system is to be averted -- will have a catastrophic effect on the world’s industrial giants: 55% of the exports of the EEC (taken as one trading bloc), 46% of the exports of Japan and 46% of the US and Canada’s exports now find their market in the backward countries. This collapse of the backward countries as a market has put at risk half the exports of the industrialized countries! The growing economic and political risks of continued massive loans to the Russian bloc are now removing another crutch on which the growth of world trade has depended. Finally, the US has begun to take rigorous steps to reduce its own payments and trade deficits so as to prevent another and more devastating dollar crisis. Such a policy by Washington, however, means that the US can no longer play the role of locomotive of the world economy -- a role in which no other country can possibly replace it.

The resultant stagnation and impending decline in world trade will have a devastating effect on industrial production in the US, Japan and the EEC, where the domestic market is -- as we have seen -- already super-saturated. Japan and Europe have long been absolutely dependent on export markets in the US, the backward countries and - particularly in the case of Europe -- the Russian bloc to maintain their industrial activity. American capitalism, long protected from the vicissitudes of world trade by a huge domestic market, is today hardly less dependent on exports than the rest of its bloc: exports now account for an unprecedented 20% of domestic industrial production.

It is this reality of a deepening world slump that has lead even representatives of the bourgeoisie, such as the authors of France’s New Five Year economic plan to point to the certainty that “tomorrow will be worse than today”. Revolutionary Marxists (who alone can understand why the course of the economic crisis must lead capitalism to the abyss) who can see that this historic crisis has created the very preconditions for the destruction of capitalism by the proletariat, can only respond by a whole‑hearted “welcome the depression!”

Having traced the course of the economic crisis, we now want to briefly sketch the economic policies with which the capitalist class in both the American and Russian blocs will attempt to respond to the global depression.

The response of the bourgeoisie

State capitalism

In the American bloc, the economic crisis is greatly accelerating the tendency towards state capitalism[4]. State capitalism cannot simply be reduced to nationalization of the means of production -- which is but one particular manifestation that it can assume. One of the architects of state capitalism in the 1930’s, Hiram Schacht, Hitler’s first economic Czar, showed in reality what the basic principle of state capitalism is: “der Stadt am Stever der Wirtschaft” (the state as rudder of the economy). Within the framework of the anarchy of the world market, whose sole regulator is ultimately the capitalist law value, it is the state which charts the course for the economy of each national capital. This can be clearly seen in the case of France, under the centre-right government of Giscerd-Barre. The state has selected “strategic” industries, such as nuclear power, aerospace and telecommunications, in which it plans to invest or direct the investment of billions of dollars, while at the same time it has decided to wind down certain traditional industries such as steel, shipbuilding and textiles. Using a combination of nationalization, subsidies and state orders, indicative planning and political pressure, the French state is orchestrating mergers (the reorganization of the special steels industry, the centralization of truck making in the hands of state-owned Renault), creating new industrial groups (the formation of a telecommunications trust, beginning with Matra’s takeover of Hachette) and is maneuvering foreign capital out of key sectors ofthe economy (the takeover ofEmrain-Schreider by Paribus).

In completing the process of organizing each national capital into a single economic bloc, the capitalist state is faced with the dilemma of adopting a coherent fiscal and monetary policy with which to steer the economy in the midst of a simultaneous collapse of industrial production and galloping inflation. Today, no major western country is seriously contemplating a thoroughgoing reflationary policy; the specter of hyper-inflation and the definitive collapse of its currency precludes the massive public works programs which Hitler in Germany, the Popular Front in France or Roosevelt in the US could institute in the 1930’s, when the collapse of production had brought with it rapidly falling prices. However, the alternative of a deflationary policy, if it seems the only way to prevent hyper-inflation, will bring about a further disastrous plunge in industrial production, profits and investment (as well as a drastic rise in unemployment). In Britain where the Tory government of Margaret Thatcher has resorted to a deflationary of policy (albeit with inconsistencies), the results have been catastrophic for capital: industrial output down 15%; since 1979 leading British ‘multinationals’ like GKN and Lucas which had made profits even in the downturn of ‘67, ‘71, and ‘74-‘75 chalked up losses; bankruptcies rose 50% in 1980 while unemployment increased by 900,000 last year alone. This de-industrialization, which is turning Britain’s manufacturing heartland into a desert, has also provided the Treasury with a pyrrhic victory: the annual rate of inflation has come down from over 20% to a still ominous 13%. Small wonder that the Confederation of British Industry (the organ of industrial capital) has frantically called for a reversal of Thatcher’s deflation by way of a massive reflationary program of public investment (roads, pipelines, nuclear energy, transport and communications) to save them from the impending catastrophe.

‘Supply-side’ economics

The bankruptcy of both orthodox def lationary policies and classical reflationary policies in the face of the combined onslaught of overproduction and inflation has led to a frantic search for ‘new’ economic nostrums on the part of the bourgeoisie and its intellectual. hangers-on. The latest of these is supply-side economics, to which an important part of the Reagan administration is firmly committed. The basis of supply-side economics is the belief that far-reaching cuts in tax rates (primarily for business and the rich) will produce such an increase in investment and a concomitant rise in industrial output that government revenues will actually rise and a balanced budget be achieved. The fallaciousness of this ‘reasoning’ will be quickly revealed if Reagan’s $54 billion tax cut is implemented unmodified and without the drastic budget cuts that the deflationists who run the Treasury and Federal Reserve Board want: the billions cut from taxes will not flow into investment in new productive plant or businesses at a time when there is already a huge overproduction of capital; rather these billions will fuel speculative activity, bringing a dramatic collapse of paper values one step closer, or will generate a short-lived boom in unproductive consumption by the rich, which will fuel the inflation which is ravaging the economy. Moreover, behind the extreme right rhetoric of its partisans, supply-side economics turns out to be merely a variant of the Keynesianism which has dominated the world economy since the 1930s. The public works projects of traditional Keynesianism and the tax cuts of supply-side economics both vainly seek to compensate for a chronic lack of effective demand relative to the mass of commodities which a hyper-developed industrial apparatus spews forth. And in a world in the grip of galloping inflation, any such attempts to make up for the lack of demand by budget deficits risks pushing capitalism over the abyss.

Attack on workers living conditions

The more the devastating blows of the world crisis destroy the very possibility of coherent economic policy, the more the bourgeoisie is driven to rely on a direct assault on the living conditions of the proletariat as its primary reaction to an objective reality which has escaped all control. By attempting to drastically alter the ratio between wages and surplus value, the bourgeoisie cannot relieve the problem of global overproduction which bars an economic recovery whatever the rate of profit may be; however, such a policy - if it is successful - can increase the competitiveness of national capital at the expense of its rivals. This has brought about a two-pronged offensive by capital. First, against employment: drastic cuts in the workforce, with a consequent ‘rationalization’ and speed-up for the remaining workers is vital for the survival of each enterprise (though the growth of unemployment only exacerbates the difficulties of each national economy as a totality); in Britain, for example, GKN has shed 27% of its workforce over the past 15 months, while British Steel has laid-off 60,000 workers and announced that an additional 20,000 will be sacked. Second, against wages: in Belgium the unions and employers, under government prodding, signed a pact for a two-year wage deal in February, and the government has since proposed abandoning indexed wages (which rise under the impact of inflation) and a 10% cut in the wages of workers whose firms receive financial aid from the state. The economic stability of the countries of the American bloc is now absolutely dependent on the success of this offensive against the proletariat.

The Eastern bloc

The economic situation in the Russian bloc is, if anything, even more desperate than that faced by the industrialized countries of the American bloc. The cumulative effects of a chronic scarcity of capital, the growing obstacles to loans from the West with which to purchase the technology that the Russian bloc lacks, the ever shrinking market for its export industries, have combined to put an end to the ‘goulash socialism’ with which first Khrushchev and then Brezhnev sought to contain the explosive outburst of class struggle which the death of Stalin had unleashed throughout the bloc. Draconian austerity and a new direct assault on the miserable living and working conditions of the proletariat is the real basis of the new Five Year Plan unveiled at the 26th Congress of the Russian Communist Party this year. In his report to the Congress, Brezhnev said that Russia will “achieve more while using fewer resources in production” under the 1981-85 Plan. Here was the veiled admission of the scarcity of capital. The switch to more intensive methods of production was no longer, according to Brezhnev, “a choice but a necessity”. The effort to raise productivity by 17-20% over the next five years, with less capital investment than in the previous five, can only mean that not productivity (which is dependent on constant capital), but the intensity of labor must grow. Brezhnev’s report, therefore, announced that the Russian economy must henceforth depend to an ever-increasing extent on the extraction of absolute surplus value rather than relative surplus value -- precisely the same course that capital had embarked upon in the American bloc. In the East too, then, the very existence of the capitalist regime depends on the bureaucracy’s success in this attack on the working class.

Inter-imperialist antagonisms

As the curve of the economic crisis spirals upwards, it intensifies the inter-imperialist antagonisms to the breaking point. There is a direct and immediate link between the deepening world economic crisis and the clashes between the imperialist blocs. For capital, there is only one ‘solution’ to its historic crisis: inter-imperialist world war. The more quickly the various economic palliatives prove futile, the more deliberately each of the imperialist blocs must prepare for a violent redivision of the world market.

The Reagan Presidency corresponds to a new determination by the American bourgeoisie to assume an increasingly bellicose posture around the world. Underlying this heightened aggressiveness is the bourgeoisie’s growing recognition that war with Russia is its only real option -- a view not usually so openly expressed as it was by Richard Piper, the Russian specialist at the National Security Council, when he said in March that war was inevitable if the Russians did not abandon ‘communism’. The strategy that is emerging within the ruling circles of American imperialism is no longer based simply on the view that its Russian antagonist must be prevented from breaking out of its Eurasian heartland; today the conviction is growing in both the Pentagon and on Wall Street that having established its military hegemony up to the banks of the Elbe after two world wars, America must now finish the job and extend its domination beyond the Urals. This is the real meaning behind the Reagan Administration’s determination to increase military spending by 7% annually in real terms (so that it will account for more than a third of the Federal Budget). The 200,000 man Rapid Deployment Force, the string of bases in the Middle East (including the ultra-modern installations in the Sinai that America hopes to take-over when Israel withdraws next year), the new “strategic consensus” that Secretary of State Haig is forging in the area stretching from Palestine to Egypt (and significantly taking in Iraq), the project for a 600 ship navy by 1990 and the new manned bomber for the Air Force, constitute so many direct preparations for offensive war in the coming decades.

While the strategic balance between the Russian and American blocs has continued its onward shift in favor of Washington (the Russian army is bogged down in Afghanistan, an upsurge of the working class in Poland may yet force the Kremlin bureaucracy to attempt to crush the proletariat, which even if successful will tie down an immense army of occupation and disrupt the Warsaw Pact), this does not mean that Russian imperialism will now adapt a defensive strategy. As we pointed out in our report to the Third Congress of the ICC, the economically weaker Russian bloc can only hope to counteract America’s overwhelming industrial might by seizing the advanced industrial infrastructure of Europe and/or Japan. Russia’s strategy of seeking domination of the oil-rich Middle East has as its primary aim to make Europe and Japan as dependent on Moscow for the fuel to run their industry as they now are on the US, and thus detach them from the American bloc. The growing bellicosity of the US can only increase the desperation of the Kremlin bureaucracy to make its bid in the Middle East while there is still any chance of success. To this must be added another factor which is pushing Russian imperialism down the path of military adventure: the scarcity of capital with which to develop her Siberian oil reserves means that both her war industries and her capacity to control her bloc by providing so vital a resource will soon be at risk -- all of which will only intensify the pressure to grab the Arabian oil fields in the coming years.

The pursuit of these warlike strategies by Russian and American imperialism is dependent on the further consolidation and strengthening of their respective blocs. However, the very deepening of the economic crisis which is pushing American imperialism to more directly plan for war is also creating stresses and strains within the Western Alliance. Japan’s massive export offensive, which produced an EEC trade deficit with Tokyo of $11.5 billion and an American trade deficit with Japan of $12.2 billion in 1980, has provoked a growing protectionist sentiment on the part of powerful factions of the bourgeoisie in both Europe and America. While the US has moved quickly to assert the cohesiveness of its bloc through pressure on Japan to ‘voluntarily’ limit its exports and to remove its own barriers to imports and foreign investment, the clamor for protectionism (and even autarky) by bourgeois factions in Europe is a growing danger to which Washington must respond.

While France and Britain have resolutely backed the US in its increasingly aggressive posture towards the Russians, America’s pressure on Europe to reduce its trade links with the Russian bloc and to have second thoughts about its participation in the projected natural gas pipeline from Siberia, has run into growing resistance -- particularly from West Germany. Eastern Europe and Russia are one of the few markets where German (and more generally European) capital does not face stiff competition from the US and/or Japan. The limitation of trade and economic links with Russia, which America’s strategy entails, will considerably reduce the small degree of autonomy which German capital has acquired since the last war. To these economic considerations must be added the fact that important segments of the European bourgeoisie still hesitate to accept all of the consequences of the strategy Washington wants to impose (the basing of Pershing II missiles in Europe) because a war would immediately turn Europe into a bloody battlefield. Nonetheless, to the degree that these hesitations are not just a facade to divert the proletariat from its own class terrain or a cloak behind which stand pro-Moscow factions of the bourgeoisie, they will ultimately give way to the impervious necessity to strengthen the bloc as it prepares for war.

As Russian imperialism moves to strengthen its bloc, it is encountering resistance on the part of certain of the bureaucracies of Eastern Europe. The Romanian and Hungarian bureaucracies in particular are loathe to put their own complex trade and economic links with Western Europe at risk, as it is only through these links that they have achieved any autonomy vis-a-vis Moscow. Nevertheless, the growing dependence on Russian loans (as these countries reach the limits of their creditworthiness in the West), reliance on Moscow for raw materials, and the ominous Brezhnev Doctrine, will ultimately prevail over the hesitations of the little Stalins.

****************************

If the upward curve of the economic crisis inexorably drives the bourgeoisie towards inter-imperialist war, the outcome of the historic crisis is not determined by the course of the economic crisis alone. It is the intersection of the curve of the economic crisis and the curve of the class struggle that determines whether the historic crisis will end in inter-imperialist world war or proletarian revolution.

If the upward curve of the economic crisis intersects with a downward curve of the class struggle (as in the 1930s) imperialist war is inevitable. If, however, the wave of the economic crisis intersects with an ascendant curve of class struggle, then the road to war is barred and an historic course towards class war between the bourgeoisie and the proletariat is on the agenda. The present ascendant course of class struggle is today the real key to the international situation. The menace of the proletariat increasingly determines the actions of the capitalist class everywhere. The vast arrays of weapons with which the capitalist classes of both blocs have armed themselves to fight an inter-imperialist war are now being prepared for use in a class war. The strengthening of the blocs, which is a pre-requisite for war against the rival bloc, is now a direct and immediate preparation to confront the proletariat wherever it challenges the role of capital.

[1] The fact that Marx did not live to write the projected volumes on ‘foreign trade’ and the ‘world market’ of his vast analysis of ‘the system of bourgeois economy’ meant that his treatment of this link is somewhat one-sided, with the axis on the over-accumulation of capital due to the fall in the rate of profit. Based on Marx’s own analysis in Capital and Theories of Surplus Value, it is the task of revolutionary Marxism to more clearly reveal the complex inter-action between overproduction of capital and over-production of commodities which a correct understanding of the immanent tendency of capitalism to saturate the world market then makes possible.

[2] While official and semi-official statistics in every country grossly distort the real state of the economy, the figures for industrial production correspond better to the real level of economic activity than the figures for GNP in which – among other things – the distinction between productive and unproductive labor (which is vital for determining the real conditions of a capitalist economy is completely denied.

[3] A 2.6 percent drop in industrial production during the third quarter of 1980 was quickly followed by a massive dumping on foreign markets (particularly the EEC and the US) which has yet to run its course.

[4] In the Russian bloc, in part as a result of the expropriation of private capitalists by the victorious proletariat in 1917-18, in part as a result of economic backwardness which made the nationalization of the means of production an absolute necessity if capitalism was to survive and an imperialist policy pursued, “private” capital has been virtually eliminated.

General and theoretical questions:

- Imperialism [2]

Recent and ongoing:

- Economic Crisis [3]

Introduction to the Reports and Resolutions of the Fourth ICC Congress

- 2314 reads

"Run, comrade, the old world is behind you"

History is accelerating. The gaping wounds of the old world are getting deeper and multiplying.

In one year, hunger has killed more people in the third world than during the six years of World War II. Workers in the so-called ‘communist' countries are experiencing food shortages just like during wartime. The economy of the western bloc is trapped in an irreversible downward spiral, throwing millions of workers out of work.

The only form of production which is really increasing is arms production.

At the same time, the response by the working class -- from Brazil to China, from Britain to Poland -- is growing wider, deeper, and increasingly determined, raising the question at a practical level of the necessity for the internationalization of proletarian action in all countries.

The struggles in Poland have forced the whole world once again to speak of "what the workers have done". The revolutionary class which exists within the working class is once again clearly visible for all to see.

And this has led to a rapid acceleration of history. The old world is falling apart and at the same time its gravedigger is raising its head.

The wind from Gdansk is a sign of the revolutionary storms which will soon follow.

Two years ago at our Third Congress (cf International Review 18) we said that the 1980s would be "The Years of Truth". Events have already confirmed this statement.

More and more revolutionaries will be faced with the problem of understanding and analyzing things ‘calmly', at a time when events are moving faster all the time.

The Fourth Congress was permeated by the new rhythm of history, and the organization was able to get a clear idea of the extent and nature of the difficulties that this ‘acceleration' entails for revolutionaries.

Marx said in the Communist Manifesto, that "theoretically (communists) have over the great mass of the proletariat the advantage of clearly understanding the line of march, the conditions, and the ultimate general results of the proletarian movement." But this advantage isn't given to them automatically or miraculously as soon as they constitute themselves into a political organization. They can only acquire it through a systematic collective work, in which their analyses are constantly confronted by living, historical reality, as well as by a generalized, on-going debate within organizations.

The texts from the 4th Congress which we are publishing here illustrate the effort of the Current to really understand "the line of march, the conditions, and the ultimate general results of the workers' movement."

The reports and resolutions are the texts which introduced and concluded the debates. The "Counter-resolution on the Class Struggle" was a contribution to the debate, developing a point of view different from the "majority" view finally adopted by the Congress.

The report "Generalized Economic Crisis and Inter-Imperialist Antagonisms", as well as the "Resolution on the Crisis", outline the perspectives for the aggravation of the economic crisis and the evolution of the tension between different capitalist powers and imperialist blocs.

The report "Perspectives for the International Class Struggle (A Breach is Opened in Poland)" and the "Resolution on the Class Struggle" show the stage reached in the evolution of the confrontation between the two principle classes in society. They analyze the strengths and weaknesses, not only of the proletariat, but also of its mortal enemy: the world bourgeoisie.

The text "The Historic Conditions for the Generalization of Working Class Struggle" addresses the principal problem raised by the workers' struggles in Poland: the necessity for the internationalization of proletarian struggles, which will enable them to display their revolutionary force.

The "Counter-Resolution on the Class Struggle" (signed Chenier) concentrates above all on the relation between the development of the political crisis of the bourgeoisie and that of the proletarian struggle. As opposed to the resolution adopted by the Congress which emphasizes the efforts of the bourgeoisie to develop a single international strategy to confront the proletariat (‘the left in opposition'), and to respond in a coordinated way to the threat posed by the international working class, the text by Chenier emphasizes above all the "senility and incapacity (of the bourgeoisie) to become a homogenous bloc when faced with its historical enemy."

Taken together, these texts will show the reader the stage of development of the general analysis of the historical situation reached by the ICC at its 4th International Congress.

Life of the ICC:

Perspectives for the International Class Struggle: (A Breach is opened in Poland)

- 1925 reads

"The theoretical conclusions of the communists are in no way based on ideas or principles that have been invented, or discovered, by this or that would-be universal reformer.

They merely express, in general terms, actual relations springing from an existing class struggle, from a historical movement going on under our very eyes." (Communist Manifesto)

1. Years of Truth

"In the ‘60s, the bourgeoisie gave us misery in exchange for crumbs, in the ‘70s, they gave us more misery in exchange for promises; with the ‘80s we are in for still more misery in exchange for....... misery!" Accion Proletaria[1]

1. The present state of the capitalist crisis is pushing the two fundamental historic classes -- the proletariat and the bourgeoisie -- towards a fight to the death, a fight stripped of all ambiguity, a fight to impose their respective historic alternatives: Revolution or War, Communism or Barbarism.

2. The bourgeoisie has seen the bankruptcy of all the plans for economic ‘recovery' that it tried out in a thousand different ways during the ‘70s. Each failure is another proof that its only way out is a third imperialist world war.

On the other hand, the continued and undefeated resistance of the proletariat (whose highest expression is the struggle in Poland) forces the bourgeoisie to face up to the ‘social question'; that is to say, the whole axis of its economic and political drive towards war can only be a strategy for confronting and defeating the proletariat.

3) For the proletariat, the perspective of a draw up a balance sheet of the proletariat's ‘solution' to the crisis within capitalism, experience in its developing struggle, which disorientated and slowed down its struggle during the ‘70s, is giving way to the bitter reality of a radical, absolute, and permanent decline in its standard of living. Increasingly, the misery imposed by capitalism ceases to be a merely quantitative phenomenon. The proletariat now faces the qualitative reality of degradation, humiliation and insecurity in every aspect of its existence.

The proletariat is learning that purely economic struggles and confrontations that remain partial and limited, end up having no effect on the bourgeoisie, and that the relative and momentary crumbs won in the great battles of 1965-73 have disappeared without trace over the last five years, giving way to an unprecedented and unrestrained decline in its living conditions. All this points to one and only one perspective: a generalized confrontation with capital with a perspective of revolution.

4) These overall historic conditions form the starting point of our evaluation of the present state of the class struggle. The question posed in this report is: how do the proletariat and the bourgeoisie respond to their historic crossing of the ways? From here, we go on to analyze the strategy and weapons used by the bourgeoisie and its strong and weak points.

2. The response of the bourgeoisie

5) At the 3rd ICC Congress we pointed to the reality of the world bourgeoisie's political -crisis and analyzed in detail its characteristics. Its origins -- which we can now determine with greater hindsight -- lie in the inadequacy of the bourgeoisie's policies in the face of the rise of the class struggle beginning in ‘78, and in the overall situation that we have defined in the previous section.

This political crisis has given rise to a complete reorientation of bourgeois strategy in particular towards the proletariat. This reorientation of its apparatus and political activity has allowed the bourgeoisie to act more coherently and to undertake a more systematic, concentrated and effective campaign against the proletariat. In the short term, the bourgeoisie is strengthened, though, as we shall see later, this strategy will weaken it in the long term.

6) As we pointed out at the 3rd Congress, the main axis of this reorientation has been the left's passage into the opposition, and consequently, the right's accession to power. But before analyzing this axis in detail, we aim to examine the ideological framework that characterizes bourgeois policies as a whole in the present period.

Capitalist domination rests on two foundations. One is that of repression and terror, while the other, which hides and reinforces the first is that of ideological mystification. This second foundation always relies on a material basis which gives it its credibility. While it contains a whole series of mystifications fed from capitalism's deepest roots (democracy, human rights), bourgeois ideology as a whole -- that is to say, all those mystifications and ‘alternatives' that maintain its domination -- must adapt itself to the different conjunctures imposed by the crisis, the class struggle and inter-imperialist conflict. If it fails to do this it risks losing all its credibility and, therefore, its grip on the proletariat.

During the ‘70s, this ideological framework revolved around the illusion that the workers, by making a whole series of sacrifices and accepting policies of increasing austerity, could get out of the crises and win back their lost ‘prosperity'. Through the myth of a national and negotiated solution to the crisis, which was incarnated in the perspective of the left in power, and whose ever-present ideology was ‘the advance of progressive forces towards social change' the bourgeoisie was able to maintain its domination, momentarily restraining and paralyzing the workers' struggles, making them swallow ever stronger doses of austerity, and rebuilding its national unity around these plans.

The 3rd Congress registered the crisis of this ideological orientation, pointing out the overall objective conditions which have broken it up. At the same time it noted the renewal of the proletarian struggle, which was developing as both cause and effect of this weakening of bourgeois domination. Had the bourgeoisie maintained the same political and ideological orientations of the previous phase, the dangerous vacuum appearing within its system of social control would have deepened further. The last two years have born witness, through a series of ideological and political crises, the process whereby the bourgeoisie has reorientated its strategy and ideology.

The bourgeoisie has openly recognized the seriousness of the crisis. It now presents us with the terrifying spectacle of the catastrophes and dangers that menace the ‘national community' and speaks straightforwardly of the perspective of war. This is the new language of ‘truth' and ‘sincerity'.

Given this somber, demoralizing and futureless perspective, where the ‘national community' is supposed to be under threat from all kinds of shadowy, undefinable forces - ‘terrorism', ‘imperialist encroachment', ‘totalitarianism' etc -- there is supposedly no other remedy than to accept the most terrible sacrifices, and to swallow the policies of ‘blood, sweat and tears', to save the ‘little we have'.

The bourgeoisie is trying to recreate its national unity by means of this ‘sincerity', which aims at the complete demoralization of the working class. In this way, the bourgeoisie adapts to the chaos and decomposition of its own social system, trying to drag the proletariat down with it. Faced with the enormous responsibilities imposed by this moment in history, the workers have tended to adopt a concerned, reflective stance. The bourgeoisie is trying to take advantage of this mood and transform it into demoralization, apathy, and despair.

Naturally, the final aim of this ideological orientation can only be the defeat of the proletariat, its unconditional submission to the drive towards war. And it can only be applied through a huge campaign of division and exhaustion carried out by the left and the unions from their base in the opposition.

7) In decadent capitalism, the state, whether ‘democratic' or ‘dictatorial', is transformed into a monstrous totalitarian apparatus which stretches its tentacles into the whole of social life, and submits the proletariat to an absolute and systematic occupation. In the countries of ‘democratic' totalitarianism this occupation is the specific function of the parties of the left (Stalinists, social democrats, and their leftist hangers-on).

As we pointed out at the 3rd Congress, the orientation of the left in power which predominated during the ‘70s resulted in a tremendous erosion of its apparatus. This weakened its hold on the proletariat and reduced its ability to fulfil its specific function within he bourgeois state -- that is to say to straitjacket the proletariat. All this has produced a profound crisis within this apparatus, which has been driven to take up a position where it can effectively carry out its role -- in other words, in opposition.

In fact, it is only in opposition (or rather, liberated from all direct governmental responsibility) that the left and the unions can devote themselves without any ambiguity to their specific role of stifling any attempts at workers' struggle, and hemming the workers in behind capitalism's plans for national solidarity and war.

But the left's passage into opposition is not simply a change of tactic to restore its control over the workers; it is also the best way of integrating this bourgeois faction in to capitalisms overall strategy, which is basically to demoralize and defeat the proletariat in order to open up the road to war.

A. Because it is only within a general orientation of ‘opposition' that the left and the unions are able to imprison the workers in tactics based on defensiveness and desperation:

-- isolated, corporatist struggles atomizing the workers in all kinds of divisions by factory, by trade etc.

-- humiliating and exhausting actions: hunger strikes, sit-ins, petitions to the authorities and public personalities.

-- reducing solidarity to individualist and moralist forms that systematically lead to a feeling of impotence and division.

-- deliberately fomenting in the workers a distrust in their own self-activity and self-organization, leading them to trust in the ‘mediation' of all types of institutions, organisms and ‘progressive' personalities.

B. Because only from the opposition can the left and the unions make credible their alternative of sharing out misery by accepting the imperatives of the national economy. This permeates all their approaches to the struggle.

The left and the unions adapt themselves to the instinctive consciousness of the workers who know that in the present situation there's little possibility of winning immediate demands. To avoid the necessary leap of the workers to a higher level of massive struggles, the left and unions attempt to transform that consciousness into a defeatist vision: facing the crisis the only thing to be done is to share out the misery amongst everybody. This vision is 100%consistent with the strategy of isolating and wasting away struggles. It is the best way of leading workers towards the logic of national solidarity. Within the framework of a ‘threatened national community', workers should accept the greatest sacrifices as long as they receive a ‘just and equal' treatment. In order to obtain it, they have to struggle against all the parties and bosses who are not for ‘solidarity', who are ‘anti-democratic' and ‘anti-patriotic', etc.

Paraphrasing Marx, the whole aim of the left and the unions is to ensure that workers don't see in their misery anything except misery, to prevent them seeing that their present misery is preparing the basis for definitively abolishing this misery.

C. Because only from the opposition can the left drown workers in the ideology of demoralization and nihilism that permeates the plans of the bourgeoisie as a whole. From within that perspective, the left,

-- turns reality on its head by presenting its passage to the opposition as resulting from the coming to power of the right. It implies that this is the result of a defeat of the workers and of a failure of the expectations of ‘social change' and ‘radical reforms' prevalent in the ‘70s. Everywhere it asserts that society is becoming ‘more right-wing', and workers too.

-- attempts to ‘prove' that workers are ‘defeated' and becoming more ‘right-wing', using as proofs the present maturation of workers' consciousness, with its apparent apathy and refusa1 to struggle under unfavourable conditions. In this way, the left tries to demoralize and later defeat the workers.

-- deliberately offers no ways out of the present situation except the very demoralizing ones of accepting misery, sacrifices for the nation, and struggling defensively for old myths that nobody believes in anymore, such as ‘socialism', ‘democracy', etc. All this essentially obeys the need to demoralize and discourage workers, to make them suffer the barbarous misery that the bourgeoisie imposes.

In reality the role the left in opposition is similar to that of a ‘workers' lawyer who says that he's doing everything possible for them but claims that ‘times aren't so good', ‘the enemy is powerful', and since ‘the client doesn't co-operate', there's not much he can do.

D. Because it is only from the opposition that the left and the unions can presently unfold a whole panoply of broad, flexible tactics for confronting and dispersing the workers' struggles. The experience of these last years show us this variety of tactics used by the left and unions:

-- accepting the generalization of the class struggle, including some of its violent reactions, but at the same time totally strangling their self-organization (as was the case in Longwy-Denain);

-- allowing a local and short-lived development of self-organization and generalization of the class struggle, but maintaining a firm control on the national scale (British steel strike);

-- establishing a ‘cordon sanitaire' around a radical and self-organized struggle, in order to totally block its generalization (Rotterdam);

-- sharing out roles of ‘moderates', and ‘radicals' between two factions of a trade union (New York subway), between two unions (as in France or Spain) or between the Stalinist party and the unions (Fiat, Italy), with the aim of retaining overall control over the workers;

-- anticipating workers' discontent through fake struggles that at times can achieve a massive and spectacular character (Sweden);

-- impeding the maturation of workers struggles by provoking premature clashes under unfavourable conditions.

This broad rainbow of tactics also allows the left and the unions to better conceal themselves in front of the workers. These tactics allow them to dilute their responsibilities, to wash their faces from time to time, to present themselves not as a unified and monolithic apparatus, but as a ‘living, democratic, organ', where all sorts of tendencies can co-exist. This makes the denouncing of the unions and the left a more difficult and complex task.

In a general way, we can conclude that the turn of the left towards the opposition means a short term reinforcement of their control of the class, which allows them to develop a tactic of attrition, isolation and demoralization of the workers' struggles. This tactic flows from the general strategy of the bourgeoisie aimed at the demoralization and defeat of the proletariat.

But, in the longer term, in contrast to the ‘30s, such a turn does not mean that the left has the capacity to lock the working class inside a bourgeois perspective dressed up as a ‘worker's alternative', or to carry out physical shackling of the proletariat, its subordination to a naked and asphyxiating control without any political justification.

8) The perspective of the left in opposition is complemented by two other elements of the present global strategy of the bourgeoisie:

A. The systematic reinforcement of repression and state terror;

B. The ideological campaigns of pro-war and nationalist hysteria.

A. All the states in the world are quantitatively and qualitatively developing the instruments of their repressive and terroristic apparatus (police, courts, army, propaganda). The goal of all this is:

-- to create a mechanism which can be combined with the tactics of attrition and dispersion favored by the left and the unions;

-- to prevent the generalized confrontations that are maturing today. This massive reinforcement of the state's terrorist arsenal is justified and supported wholeheartedly by the left which:

-- participates without hesitation in the anti-terrorist campaigns and ceaselessly calls for the repressive reinforcement of the state;

-- demands more repression and more police under the excuse of anti-fascism and anti-racism (Belgium);

-- never tires of demanding the insatiable increase of military budgets in the name of ‘the defense of national sovereignty'.

Its protests against repressive acts never question this reinforcement of the state. The left limits itself to uttering pious moanings against the most explicit and extreme aspects and criticizes (in the name of social peace and the national interest) the unthinking, excessively partisan or too provocative use of repression.

In reality, in spite of their formal separation and their apparent antagonism, the trade union and left apparatus and the police apparatus complement each other in front of the class struggle. Repression is unleashed on the workers once they have been isolated and disarmed by the practices of the left and the unions; at the same time, by being directed selectively to the more radical sectors of the workers, repression pushes the majority of the workers towards accepting the methods and defeatist alternatives of the left and the unions.

8. On top of the fundamental ideological orientations that we mentioned in point 6, the bourgeoisie has attempted to develop hysterical pro-war and nationalist campaigns which aim to politically weaken the class and to mobilize it along with the rest of the population behind its plans for sacrifice and war.

The deep exhaustion of the old mystifications (anti-fascism, anti-terrorism, democracy, national defense, etc.) means that these campaigns have in general had little success. Rather than taking a coherent and systematic form, they have been based largely on the exploitation of particular events;

-- the case of the hostages was utilized in the USA in order to prop up the campaign of a national solidarity;

-- the acts carried out by the extreme right, in France, Italy and Belgium have resulted in anti-fascist campaigns;

-- the threat of invasion by Russia has been used in Poland as a ,justification for social peace;

-- anti-terrorism in Spain and Italy;

-- the general elections in Germany were the springboard for a gigantic campaign of war preparations under the guise of pacificism.

The balance-sheet of these campaigns is not positive for the bourgeoisie:

-- at least in the immediate, they have not had an impact on the proletariat;

-- their mystifications have been exposed and the bourgeoisie's prestige has decreased due to the internal contradictions of the events involved (i.e, the earthquake in Italy or the Arregui case in Spain vis-a-vis the anti-terrorist hysteria);

-- these campaigns have mainly attempted to foment an atmosphere of insecurity, confusion and demoralization. They have not been as successful as part of a coherent political strategy for the ideological mobilization of the class the bourgeoisie is far from having such a strategy today.

9) Throughout this section we have analyzed in detail the bourgeoisie's response to its present historical dilemma. The question we must ask ourselves is: does that answer mean a strengthening of the bourgeoisie vis-a-vis the proletariat? Can such a response defeat the proletarian resurgence which began in 1978?

For us, the whole orientation of the politics of the bourgeoisie over the last three years have led to a short term strengthening of the ruling class; but it also expresses a position of weakness leading to an effective weakening in the long term.

We are now going to develop this apparently contradictory thesis.

In the short term, this orientation allows the bourgeoisie:

A. to use coherently and without compromise all of its social and political forces:

-- the right, in power, organizes a frontal attack against the class without any risk of losing prestige or contradicting its basis of support in society;

-- the left, placed in opposition, can dedicate itself, without any handicaps, to demobilizing the workers, and exhausting their struggles, thus aiding capitalism's attacks, and creating a climate of demoralization and impotence in order to prepare defeat in the future;

B. to concentrate coherently and cohesively all its forces and instruments against the proletariat. Today, in spite of the internal conflicts of capital and its weaknesses and anachronisms, we are seeing a systematic and combined offensive of the whole of its forces against the workers. There is a degree of coordination, a capacity for working together, and a unity of strategy never seen in the past amongst the bourgeois forces. Left and right, bosses and unions, repressive bodies and the media, church and secular institutions, etc., coordinate their efforts in the same anti-proletarian direction. They know how to converge from their various, divergent and contradictory positions to a single front line defending the bourgeois order. This means a higher level of bourgeois action against the working class in contrast with the previous period, when the bourgeoisie used repression without really linking it to mystifications or used mystifications without openly employing repression;

C. to develop a strategy of isolating and exhausting flare-ups of class struggle, of drowning them in the general climate of demoralization, with the aim of facilitating the total, final defeat of the proletariat and opening up a definitive course towards war.

This reorientation of the bourgeois state apparatus is having a certain immediate effectiveness. It has, up to a point, managed to contain the development of class antagonisms in the main proletarian concentrations, giving the state a spectacular facade of force and power. Now, even if we must not underestimate at all the force of the bourgeoisie and must denounce in detail and to the maximum degree its campaigns and maneuvers, such denunciations would be useless if they weren't informed by a clear vision of the weakness and fragility, the profound contradictions, underlying the power of the bourgeoisie today.

We must not forget that all this reorientation has taken place with the aim of confronting the proletarian reemergence since 1978; in other words, that the starting point of this reorientation is a position of weakness and surprise on the part of the bourgeoisie. As the battles in Poland show, the present situation continues to be determined by the inability of the bourgeoisie to subordinate the proletariat and crush class antagonisms. At the present level of the capitalist crisis, such an incapacity is a grave danger for bourgeois power, because it weakens it economically and politically, deepening its contradictions and increasing its inability to drag society towards its ‘solution' to the crisis -- world war.

Therefore, the present coherence and strength of bourgeois political strategy must be essentially interpreted as the last resort, the supreme effort of the bourgeois state to avoid a generalized class confrontation.

This must not lead us to underestimate the force of the bourgeoisie, because the possibilities opened up by its recent political reorientation are certainly not exhausted, and the working class is going to go through a hard period during which the danger of being crushed by the present concentration and combination of bourgeois resources will be ever-present. But, at the same time, we cannot ignore that the decisive word is still with the proletariat. As long as the class is capable of deepening the breach opened by the massive struggles in Poland, it will be able to overcome the weight of the tremendous concentration of enemy forces facing it, and open up a process of breaking up the bourgeois front. In this process, all the aspects that today appear as strong points of capitalism will be transformed into marks of its weakness.

As we mentioned at the beginning, the present strategy of the bourgeoisie recognizes openly the breakdown of its social system, the fact that it really has nothing to offer except war. This admittance can have the immediate and dangerous effect of demoralizing the proletariat and trapping it in the barbarism imposed on it by capital. But if the proletariat manages to broaden its struggles to break the chain of isolation and attrition, the very sincerity by the bourgeoisie will create an enormous vacuum. This would allow workers to develop a revolutionary alternative because they would have clear confirmation of the chaos of the bourgeoisie's system.

"When the bourgeoisie admits that its system is bankrupt, that it has nothing else to offer except imperialist butchery, it is contributing to the creation of the conditions which can allow the proletariat to find the path of its historic alternative to the capitalist system"[2]

The left in opposition is showing its momentary capacity to stop workers' struggles and it could succeed in exhausting and sinking the immense combativity of the proletariat. But, at the same time, such a political orientation is dangerous because it has no illusory perspectives to offer the proletariat. Thus, this whole orientation can end up showing the essential character of the left and the unions as 'oppositional' appendages to capitalism's policy of war and misery, as mere instruments for the physical straight jacketing and policing of the proletariat.

Equally, the reinforcement of repression and bourgeois state terror can sow within the proletariat a momentary climate of fear and impotence, but in the long run this reinforcement shows its class character and thus the need to confront it violently without pacifist, democratic or legalist illusions.

Finally, the campaigns of nationalist and warlike hysteria launched by capital can intoxicate the proletariat with chauvinist and inter-classist poisons, but the weakness of their ideological bases and the capitalist contradictions that underlie them can lead to the contrary result: they become additional factors forcing the proletariat to clarify its revolutionary alternative and deepen its class autonomy.

The tendency for the left to go into opposition, and the reinforcement of the repressive apparatus, express a process of formal reinforcement of the bourgeois state that hides a more profound real weakening.

In the final analysis, the present facade of cohesion and strength the bourgeois front has the clay feet of a profound incapacity to transcend its internal contradictions and channel the whole of society towards bourgeois alternatives. Everything that today lurks in the darkness can be brutally exposed to the light of day if the proletariat develops a front line of massive class combats. Far from being a simple hypothesis or the faraway echo of old historical experiences, this is a real possibility clearly announced by the Polish mass strikes:

"It is not only in the struggles of the proletariat that the events in Poland prefigure what will increasingly become the general situation of all the industrialized countries. The internal convulsions of the ruling class that we can see in Poland today, including their more exaggerated aspects, are an indication of subterranean developments going on throughout bourgeois society. Since August the ruling circles in Poland have been in a state of genuine panic. In government circles, for the past five months, ministerial portfolios have been constantly changing hands. It has even got to the point that a government ministry has been entrusted to a Catholic. But the convulsions have been strongest in the most important force within the ruling class: the party."[3]

3. The response of the proletariat

10. Once we have examined the strategy of the bourgeoisie, let's make a balance-sheet of the response that the working class is giving in the present historical situation. In order to do this we have to ask ourselves the following three questions:

1) Is it becoming aware of the historic responsibilities it bears in the present situation?

2) To what extent do its most recent struggles express that awareness? Do they constitute a step forward towards the revolution?

3) What lessons and perspectives are to be drawn from those struggles?

To answer these three questions is the intention of the present section.

11. "When it is a question of making a precise study of the strikes, combinations and other forms in which the proletarians carry out before our eyes their organization as a class, some are gripped by a real panic, and the others exhibit a transcendental disdain."[4]

The process through which the working class matures its understanding of the historical situation and of the tasks that it faces is not at all simple nor self-evident.

The thought and will of the working class are expressed exclusively through its mass struggles against the bourgeois order; and when looking at these struggles we need to have an approach that captures their objective dynamic if we are to understand their true historical meaning. There is always a brutal discrepancy between the objective impact of the struggles and the subjective representations that workers make them.