International Review 57 - 2nd Quarter 1989

- 2360 reads

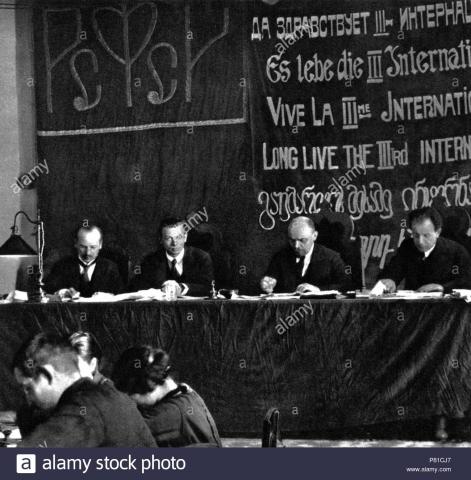

1919: Foundation of the Communist International

- 2994 reads

March 2019 marks the centenary of the foundation of the Third, Communist International, one of the high points of the international revolutionary wave which swept the globe at the end of the First World War. We will be producing a new article to celebrate and analyse this historic event, but in the meantime we are drawing readers' attention to what we wrote in 1989, 70 years after the formation of the CI; this is an article which retains its relevance today.

Amongst the many anniversaries that will be celebrated in 1989, there is one that the media and historians will not talk about other than briefly and then only with the conscious aim of distorting its significance. In March 1919 the founding Congress of the Communist International was held. As they did with the bicentenary of the foundation of the United States, the bourgeoisie's well-paid historians will celebrate the bicentenary of the French Revolution of 1789 by trumpeting the values of liberty, equality, fraternity, democracy and the nation as the absolute and definitive principles that had at last been discovered to lead humanity to ‘happiness'. Two centuries of exploitation, class struggle, misery and imperialist war, have revealed the capitalist reality behind these fine words. For the bourgeoisie, the purpose of these celebrations is to make people forget that "capitalism was born in blood and filth" (Marx), that it was born of the class struggle, and above all, that it is a transitory social form, which will disappear as all the previous modes of production have done before it.

The anniversary of the foundation of the Communist International is there to remind the bourgeoisie of 1989 that the class struggle is a reality of today's crisis-ridden capitalism, that the proletariat exists as both an exploited and a revolutionary class; it heralds the end of the bourgeoisie itself.

The international revolutionary wave in 1919

The CI's foundation awakes unpleasant memories for the whole capitalist class and its zealous servants. In particular, it reminds them of their fright at the end of World War I, faced with the mounting and apparently unavoidable tide of the international revolutionary wave: the victorious proletarian revolution in Russia in October 1917; mutinies in the trenches; the abdication of Kaiser Wilhelm and the hurried signature of an armistice in the face of mutinies and the revolt of the working masses in Germany; then the insurrection of German workers; the creation along Russian lines of republics of workers' councils in Bavaria and Hungary; the beginning of strikes among the working masses in Britain and Italy; mutinies in the fleet and army in France, as well as among some British military units refusing to intervene against Soviet Russia ....

Lloyd George, Prime Minister of the British Government at the time, best expressed the international bourgeoisie's alarm at the power of the Russian workers' soviets when he declared in January 1919 that if he were to try to send a thousand British troops to help occupy Russia, the troops would mutiny, and that if a military occupation were undertaken against the Bolsheviks, England would become Bolshevik and there would be a soviet in London:

"The whole of Europe is filled with the spirit of revolution. There is a deep sense not only of discontent, but of anger and revolt amongst the workmen against pre-war conditions. The whole existing order in its political, social and economic aspects is questioned by the masses of the population from one end of Europe to the other" (quoted in Carr, The Bolshevik Revolution, Vol 3, p .13 5 ).

We know today that the CI's foundation was the high point of the revolutionary wave which extended from 1917 until at least 1923, throughout the world, from Europe to Asia (China), and to the ‘new' world from Canada (Winnipeg) and the USA (Seattle) to Latin America. This revolutionary wave was the international proletariat's answer to World War I, to 4 years of imperialist war amongst the capitalist states to divide the world up between them. The attitude towards the imperialist war of the different parties and individual militants of the social democracy, the 2nd International swallowed up by the war in 1914, was to determine what attitude they would adopt faced with the revolution and the Communist International.

"The Communist International was formed after the conclusion of the imperialist war of 1914-18 in which the imperialist bourgeoisie of the different countries sacrificed 20 million men.

"‘Remember the imperialist war!' These are the first words addressed by the Communist International to every working man and woman; wherever they live and whatever language they speak. Remember that because of the existence of capitalist society a handful of imperialists were able to force the workers of the different countries for four long years to cut each other's throats. Remember that the war of the bourgeoisie conjured up in Europe and throughout the world the most frightful famine and the most appalling misery. Remember that without the overthrow of capitalism the repetition of such robber wars is not only possible but inevitable" (Statutes of the Communist International, adopted at the 2nd Congress, in Degras, The Communist International, Documents)

Part I: The continuity from the 2nd International to the CI

The 2nd International and the question of the imperialist war

In the Communist Manifesto of 1848, Karl Marx set out one of the essential principles of the proletariat's struggle against capitalism: "The workers have no country". This principle did not mean that workers should take no interest in the national question, but on the contrary that they should define their positions and attitudes on the subject, and on the question of national wars, as a function of their own historical struggle. The question of war and the attitude of the proletariat were always at the centre of the debates of the 1st International (1864-73), as it was in those of the 2nd (1889-1914). During most of the 19th century, the proletariat could not remain indifferent to the wars of national emancipation against feudal and monarchic reaction, and especially against Russian tsarism.

Within the 2nd International the marxists, with Lenin and Rosa Luxemburg in the forefront, were able to recognize the change in the period of capitalism's life that occurred at the dawn of the 20th century. The capitalist mode of production had reached its apogee, and reigned over the entire planet. Here began the period of "imperialism, the highest stage of capitalism", as Lenin put it. In this period the coming European war would be an imperialist and world war between capitalist nations over the distribution of colonies and spheres of influence. It was essentially the left wing of the2nd International which led the combat to arm the International and the proletariat in this new situation, against the opportunist wing, which was abandoning day by day the principles of the proletarian struggle. A vital moment in this struggle was the 1907 Congress of the International in Stuttgart, where Rosa Luxemburg, drawing the lessons of the experience of the 1905 mass strike in Russia, linked the question of imperialist war to those of the mass strike and the proletarian revolution:

"I have asked to speak in the name of the Russian and Polish delegations to remind you that on this point [the mass strike in Russia and the war, ed.) we must draw the lesson of the great Russian revolution [ie of 1905, ed.] ... The Russian revolution did not only arise as a result of the war; it also put an end to the war; without it, Tsarism would undoubtedly have continued the war" (Rosa Luxemburg, quoted in BD Wolfe, Lenin, Trotsky, Stalin).

The left carried the adoption of the vitally important amendment to the Congress resolution, presented by Luxemburg and Lenin:

"Should a war break out nonetheless, the socialists have the duty to work to bring it to an end as rapidly as possible, and to use by every means the economic and political crisis provoked by the war to awaken the people and so to hasten the downfall of capitalist domination" (quoted in the Resolution on the Socialist currents and the Berne conference, at the First Congress of the CI).

In 1912, the 2nd International's Basel Congress reaffirmed this position against the growing menace of imperialist war in Europe:

"Let the bourgeois governments not forget that the Franco-Prussian war gave birth to the revolutionary insurrection of the Commune, and that the Russo-Japanese war set in motion the revolutionary forces in Russia. In the eyes of the proletarians, it is criminal to massacre themselves for the benefit of capitalist profit, dynastic rivalry, and the flourishing of diplomatic treaties" (ibid).

The betrayal and death of the 2nd International

The 4th August 1914 marked the outbreak of the First World War. Riddled with opportunism, swept away in the flood of chauvinism and war fever, the 2nd International broke up and died in shame: its principal parties (above all the French and German social-democratic parties and the British Labor party, in the hands of the opportunists), voted for war credits, called for the ‘defense of the fatherland', and a ‘holy alliance' with the bourgeoisie against ‘foreign invasion'; in France, they were even rewarded with ministerial positions for having given up the class struggle. They received a theoretical support from the ‘centre' (ie between the International's left and right wings), when Kautsky, who had been called the ‘pope of marxism', distinguished between war and the class struggle, declaring the latter possible only ‘in peacetime' .... and so of course impossible ‘for the duration'.

"For the class-conscious workers ( ... ) by the collapse of the [2nd] International they understand the glaring disloyalty of the majority of the official Social-Democratic parties to their convictions, to the most solemn declarations made in speeches at the Stuttgart and Basel International Congresses, in the resolutions of these congresses, etc" (Lenin, The Collapse of the Second International)

Only a few parties stood up to the storm: essentially the Italian, Serbian, Bulgarian and Russian parties. Elsewhere, isolated militants or groups, usually from the Left, such as Rosa Luxemburg and the Dutch ‘Tribunists' around Gorter and Pannekoek, remained faithful to proletarian internationalism and the class struggle and tried to regroup.

The death of the 2nd International was a heavy defeat for the proletariat, which it paid for in blood in the trenches. Many revolutionary workers were to die in the slaughter. For the ‘revolutionary social-democrats', it meant the loss of their international organization, which would have to be rebuilt:

"The 2nd International is dead, defeated by opportunism. Down with opportunism, and long live the 3rd International, rid not only of deserters ( ... ) but also of opportunism!" (Lenin, Situation and Tasks of the Socialist International)

The conferences of Zimmerwald and Kienthal: Steps towards the construction of the Communist International

In September 1915, the ‘International Socialist Conference of Zimmerwald' was held. It was to be followed in April 1916 by a second conference at Kienthal, also in Switzerland. Despite the difficult conditions of war and repression, delegates from 11 countries took part, including Germany, Italy, Russia and France.

Zimmerwald recognised the war as imperialist. The majority of the conference refused to denounce the opportunist right of the social-democratic parties which had gone over to the camp of the ‘holy alliance', or to envisage splitting with them. This centrist majority was pacifist, defending the slogan of ‘peace'.

United behind the representatives of the Bolshevik fraction, Lenin and Zinoviev, the ‘Zimmerwald Left', defended the necessity of a split, and the construction of the 3rd International. Against pacifism, they declared that "the struggle for peace without revolutionary action is a hollow and deceitful phrase" (Lenin), and opposed centrism with the slogan of "transformation of the imperialist war into a civil war. This slogan, precisely, is indicated in the resolutions of Stuttgart and Basel" (Lenin).

Although the Left gained in strength from one Conference to the next, it was unable to convince the other delegates, and remained in the minority. Nonetheless, its evaluation was positive:

"The second Zimmerwald Conference (Kienthal) is undoubtedly a step forward. ( ... ) What then should we do tomorrow? Tomorrow, we must continue the struggle for our solution, for the revolutionary social-democracy, for the 3rd International! Zimmerweld and Kienthal have shown that our road is the right one" (Zinoviev, 10/6/1916).

The meeting between the lefts of different countries, and their common combat, made possible the constitution of the "first nucleus of the 3rd International in formation", as Zinoviev recognized in March 1918.

The proletariat carries out the resolutions of the Stuttgart and Basel Congresses

The 1917 proletarian revolution in Russia opened a revolutionary wave throughout Europe. The proletarian threat decided the international bourgeoisie to bring the imperialist carnage to an end. Lenin's slogan became a reality: the Russian, then the international proletariat transformed the imperialist war into a civil war. Thus the proletariat honored the Left of the 2nd International, by applying the famous Stuttgart resolution.

The war had definitively thrust the opportunist right of the social-democratic parties into the camp of the bourgeoisie. The revolutionary wave put the pacifists of the centre up against the wall, and was to thrust many of them in their turn, especially the leaders such as Kautsky into the bourgeois camp. The International no longer existed. The new parties formed by splits from the social-democracy began to adopt the name of ‘Communist Party'.

The revolutionary wave encouraged and demanded the constitution of the world party of the proletariat: the 3rd International.

The formation of the CI: Its continuity in politics and principles with the 2nd International

The new International, which adopted the name of the Communist International, was thus formed in March 1919 on the basis of an organic split with the right wing of the parties of the defunct 2nd International. It did not, however, reject its principles or its contributions.

"Sweeping aside the half-heartedness, lies and corruption of the outlived official Socialist parties, we Communists, united in the 3rd International, consider ourselves the direct continuators of the heroic endeavors and martyrdom of a long line of revolutionary generations from Babeuf to Karl Liebknecht and Rosa Luxemburg.

If the 1st International presaged the future course of development and indicated its paths; if the 2nd International gathered and organized millions of workers; then the 3rd International is the International of open mass action, the International of revolutionary realization, the International of the deed" (Manifesto of the CI, in The Five Years of the CI, ed. New Park)

The currents, the fractions, the traditions and the positions which formed the basis of the CI, were developed and defended by the Left within the 2nd International.

"Experience proves that only in a regroupment selected from the historical milieu - the 2nd International - in which the pre-war proletariat developed could the proletarian struggle against the imperialist war be pushed to its extreme conclusion, for only this group was able to formulate and advanced program for the proletarian revolution, and so to lay the foundations for a new proletarian movement" (Bilan, theoretical bulletin of the Italian Fraction of the Communist Left), no. 34, August 1936, p.1128).

Over and above individuals such as Lenin, Rosa Luxemburg, Anton Pannekoek, or even groups and fractions of the social-democratic parties like the Bolsheviks, the German, Dutch, and Italian lefts etc, there is a political and organic continuity between the left of the 2nd International and of Zimmerwald, and the 3rd International. The first Congress of the new International was called on the initiative of the Russian Communist Party (Bolsheviks) (previously the Workers' Social Democratic Party of Russia (Bolsheviks), which was part of the 2nd International) and the German Communist Party (ex-Spartacus League). The Bolsheviks were the driving force behind the Zimmerwald Left. The latter, a true organic and political link between the 2nd and 3rd Internationals, drew up a balance-sheet of its past combats as the left wing of the 2nd International, and set out the needs of the day:

"The conferences of Zimmerweld and Kienthal were important at a time when it was necessary to unite all those proletarian elements determined in one way or another to protest against the imperialist butchery. ( ... ) The Zimmerwald group has had its day. All that was truly revolutionary in the Zimmerwald goes over to and joins the Communist International" (Declaration of the Participants at Zimmerwald, quoted in Broue, op. cit.).

We insist strongly on the continuity between the two Internationals. As we have seen on the organic level, the CI did not appear out of the blue. The same is true of its program and its political principles. Not to recognize the historical link between the two means succumbing to an anarchist inability to understand how history works, or to a mechanistic spontaneism which sees the CI as solely the product of the revolutionary movement of the working masses.

Without recognizing this continuity, it is impossible to understand why and how the CI breaks with the 2nd International. For although there is a continuity between the two, expressed amongst other things in the Stuttgart resolution, there is also a rupture. A rupture concretized in the CI's political program, in its political positions and in its organizational and militant practice as the ‘world communist party'. A rupture in facts, by the use of armed and bloody repression: against the proletariat and the Bolsheviks in Russia by the Kerensky government, with the participation of the Mensheviks and the SRs, both members of the 2nd International; against the proletariat and the KPD in Germany by the Social-Democratic government of Noske-Scheidemann.

Without recognizing this ‘break within a continuity', it is also impossible to understand the degeneration of the CI during the 1920s and the combat conducted within it, then outside it during the 30s following their exclusion, by the fractions of the ‘Italian', ‘German' and ‘Dutch' Communist Lefts, to name only the most important. Today's communist groups and the positions they defend are the product of these left fractions, of their defense of communist principles and their work in carrying out a critical reappraisal of the CI and the 1917-23 revolutionary wave. Without recognizing the heritage of the 2nd International, which is the political heritage of the proletariat, it is impossible to understand the foundations of the CI's positions, nor the validity of some of the most important of them today, nor the contributions of the fractions during the 1930s. In other words, it means being incapable of defending revolutionary positions today, consistently and with assurance and determination.

Part 2: The CI's break with the 2nd International

The CI's political program

At the end of January 1919, Trotsky drew up the ‘Letter of invitation' to the CI's founding Congress, which determined the political principles that the new organization aimed to adopt. In fact, this letter is the proposed ‘Platform of the Communist International', and sums it up well. It is based on the programs of the two main communist parties:

"In our opinion the new international should be based on the recognition of the following propositions, put forward here as a platform and worked out on the basis of the program of the Spartakusbund in Germany and of the Communist Party (Bolsheviks) in Russia" (Degras, opcit.)

In fact, the Spartakusbund no longer existed since the foundation of the German Communist Party (Kommunistische Partei Deutschlands) on 29th December 1918. The KPD had just lost its two principal leaders, Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Liebknecht, assassinated by the social-democracy during the terrible repression of the Berlin proletariat in January. Thus at the very moment of its foundation, the CI suffered, along with the international proletariat, its first defeat. Two months before it was constituted, the CI lost two leaders whose prestige, strength, and theoretical abilities were comparable to those of Lenin and Trotsky. It was Rosa Luxemburg who had the most developed, in her writings at the end of the previous century, the point that was to become the keystone of the 3rd International's political program.

Capitalism's irreversible historical decline

For Rosa Luxemburg, it was clear that the war of 1914 had opened up the capitalist mode of production's period of decadence. After the imperialist slaughter, this position could no longer be contested:

"Matters have reached such a pitch that today mankind is faced with two alternatives: it may perish amid chaos; or it may find salvation in socialism" (Speech on the Program, Merlin Press).

This position was reaffirmed vigorously by the International:

"1. The present epoch is the epoch of the collapse and disintegration of the entire capitalist world system, which will drag the whole of European civilization down with it if capitalism with its insoluble contradictions is not destroyed" (Letter of Invitation, in Degras, opcit).

"A new epoch is born! The epoch of the dissolution of capitalism, of its inner disintegration. The epoch of the communist revolution of the proletariat" (Platform of the CI, ibid).

The political implications of the epoch of capitalist decadence

For all those who stand on the terrain of the Communist International, the decline of capitalism has consequences for the living conditions and struggle of the proletariat. Contrary to the ideas of the pacifist centre, those of Kautsky for example, the end of the war could not mean a return to the life and program of the prewar period. This was one point of rupture between the dead 2nd and the 3rd International:

"One thing is certain, the World War is a turning point for the world. ( ... ) The conditions of our struggle, and we ourselves, have been radically altered by the World War" (Luxemburg, The Crisis in the Social Democracy, 1915).

The opening of the period of capitalist society's decline marked by the imperialist war, meant new conditions of life and struggle for the international proletariat. It was heralded by the 1905 mass strike in Russia, and the emergence for the first time of a new form of unitary organization of the working masses, the soviets. Luxemburg (in Mass Strike, Party, and Unions, 1906) and Trotsky (in 1905) drew the essential lessons of these mass movements. With Luxemburg, the whole of the left led the debate within the 2nd International on the mass strike, and the political battle against the opportunism of the trade union and Social-Democratic party leaderships, against their vision of a peaceful and gradual evolution towards socialism. Breaking with social-democratic practice, the CI declared:

"The basic methods of struggle are mass actions of the proletariat right up to open armed conflict with the political power of capital" (Letter of Invitation in Degras, opcit).

The revolution and the dictatorship of the proletariat

The action of the working masses leads to confrontation with the bourgeois state. The CI's most precious contribution is on the revolutionary proletariat's attitude to the state. Breaking with the social-democracy's ‘reformism', renewing the marxist method and the lessons of the historical experiences of the Paris Commune, Russia 1905, and above all the insurrection of October 1917 with the destruction of the capitalist state in Russia and the exercise of power by the workers' councils, the CI declared itself clearly and without any ambiguity for the destruction of the bourgeois state and the dictatorship of the proletariat, the dictatorship of the working masses organized in the workers' councils.

"2. The task of the proletariat is now to seize power immediately. The seizure of state power means the destruction of the state apparatus of the bourgeoisie and the organization of a new proletarian apparatus of power.

3. This new apparatus of power should embody the dictatorship of the working class, and in some places also of the rural semi-proletariat, the village poor ( ... ) Its concrete form is given in the regime of the Soviets or of similar organs.

4. The dictatorship of the proletariat must be the lever for the immediate expropriation of capital and for the abolition of private property in the means of production and their transformation into national property" (ibid).

This question was an essential one for the Congress, which was to adopt the ‘Theses on bourgeois democracy and proletarian dictatorship' presented by Lenin.

The theses on bourgeois democracy and the dictatorship of the proletariat

The Theses begin by denouncing the false opposition between democracy and dictatorship. "For in no civilized capitalist country is there ‘democracy in the abstract', there is only bourgeois democracy" (ibid). The Paris Commune had demonstrated the dictatorial character of bourgeois democracy. In capitalism, defending ‘pure' democracy in fact means defending bourgeois democracy, which is the form par excellence of the dictatorship of capital. What freedom of meeting or of the press is there for workers?

"‘Freedom of the press' is another leading watchword of ‘pure democracy'. But the workers know..., that this freedom is deceptive so long as the best printing works and the biggest paper supplies are in capitalist hands, and so long as capital retains its power over the press, a power which throughout the world is expressed more clearly, sharply, and cynically, the more developed the democracy and the republican regime, as for example in America. To win real equality and real democracy for the working masses, for the workers and peasants, the capitalists must first be deprived of the possibility of getting writers in their service, of buying up publishing houses and bribing newspapers. And for that it is necessary to throw off the yoke of capital, to overthrow the exploiters and to crush their resistance" (Theses, ibid).

After the experience of the war and the revolution, to demand and defend pure democracy, as do the Kautskyists, is a crime against the proletariat, the Theses continue. In the interests of the different imperialisms, of a minority of capitalists, millions of men were massacred in the trenches, and the ‘military dictatorship of the bourgeoisie' has been set up in every country, democratic or not. Bourgeois democracy assassinated Karl Liebknecht and Rosa Luxemburg once they had been arrested and imprisoned by a social-democratic government.

"In such a state of affairs the dictatorship of the proletariat is not merely wholly justified as a means of overwhelming the exploiters and overcoming their resistance, but quite essential for the mass of workers as their only protection against the bourgeois dictatorship which led to the war and is getting ready for new wars. ( ... ) The fundamental difference between the proletarian dictatorship and the dictatorship of other classes ( ... ) consists in this, that ( ... ) the dictatorship of the proletariat is the forcible suppression of the resistance of the exploiters, that is of the minority of the population, the large landowners and capitalists. ( ... )

And in fact the forms taken by the dictatorship of the proletariat, which have already been worked out, that is, the Soviet power in Russia, the workers' councils in Germany, the shop stewards' committees, and other analogues of Soviet institutions in other countries, all these make a reality of democratic rights and privileges for the working classes, that is for the overwhelming majority of the population; they mean that it becomes really possible to use these rights and privileges in a way and on a scale that was never even approximately possible in the best democratic bourgeois republic" (ibid).

Only the dictatorship of the proletariat on a world scale can destroy capitalism, abolish classes, and ensure the passage to communism.

"The abolition of state power is the goal of all socialists, including and above all Marx. Unless this goal is reached, true democracy, that is, equality and freedom, is not attainable. But only Soviet and proletarian democracy leads in fact to this goal, for it begins at once to prepare for the complete withering away of any kind of state by drawing the mass organizations of the working people into constant and unrestricted participation in state administration" (ibid).

The question of the state was a crucial one, at a moment when the revolutionary wave was unfurling in Europe and the bourgeoisie in all countries was waging civil war against the proletariat in Russia, when the antagonism between capital and labor, between bourgeoisie and proletariat, had reached its most extreme and most dramatic point. The need to defend the dictatorship of the proletariat in Russia and the extension of the revolution, ie the power of the Soviets, internationally to Europe was posed concretely for revolutionaries. For or against the state of the proletarian dictatorship in Russia and the revolutionary wave. ‘For' meant joining the Communist International, and breaking organically and politically with the social-democracy. ‘Against' meant defending the bourgeois state, and choosing definitively the camp of the counter-revolution. For the centrist currents that hesitated between the two, it meant break-up and disappearance. Revolutionary periods do not leave any room for the timid policies of the ‘middle ground'.

Part 3: Today and tomorrow: Continuing the work of the CI

The change in period revealed definitively by the 1914-18 war determines the break between the political positions of the 2nd and 3rd Internationals. We have seen this on the question of the state. Capitalism's decline and its consequences for the proletariat's conditions of life and struggle posed a whole series of new problems: was it still possible to take part in elections and make use of parliament? With the appearance of the workers' councils, were the trade unions that had taken part in the ‘holy alliance' with the capitalists still working class organizations? What attitude should be adopted towards national liberation struggles in the epoch of imperialist wars?

The CI was unable to answer these new questions? It was formed more than a year after October 1917, two months after the proletariat's first defeat in Berlin. The years that followed were marked by the defeat and ebb of the international revolutionary wave, and so by the growing isolation of the proletariat in Russia. This isolation was the determining reason behind the degeneration of the state of the proletarian dictatorship. These events left the CI incapable of resisting the development of opportunism. In its turn, it died.

To draw up a balance sheet of the CI, obviously we must recognize it as the International Communist Party that it was. For those who see it only as a bourgeois organization, because of its eventual degeneration, it is impossible to draw up a balance sheet, or to extract any lessons from its experience. Trotskyism lays claim uncritically to the first 4 Congresses. It never saw that where the 1st Congress broke with the 2nd International, the following congresses marked a retreat: in opposition to the split with the social-democracy accomplished by the 1st Congress, the 3rd proposed to make an alliance with it in the ‘United Front'. After having recognized its definitive passage into the bourgeois camp, the CI rehabilitated social-democracy at the 3rd Congress. This policy of alliance with the social-democratic parties was to lead Trotskyism in the 1930s to adopt the policy of ‘entrism', ie entering these same parties in direct defiance of the very principles of the 1st Congress. This policy of alliance, or of capitulation as Lenin would have said, was to precipitate the Trotskyist current into the counter-revolution, with its support for the bourgeois republican government in the Spanish civil war and then its participation in the imperialist Second World War, in betrayal of Zimmerwald and the International.

Already in the 1920s, a new left was created within the CI to try to struggle against this degeneration: in particular, the Italian, Dutch, and German Lefts. These left fractions, which were excluded during the 1920s, continued their political combat to ensure the continuity between the dying CI and the ‘party of tomorrow', by subjecting the CI and the revolutionary wave to a critical reappraisal. It is not for nothing that the review of the Italian Fraction of the Communist Left during the 1930s was called Bilan (‘the balance sheet').

In continuity with the International's principles, these groups criticized the weaknesses in its break with the 2nd International. Their unsung efforts, in the deepest night of the counter-revolution during the 1930s and the second imperialist war, have made possible the resurgence and existence of communist groups today which, while they have no organic continuity with the CI, ensure its political continuity. The positions worked out and defended by these groups answer the problems raised within the CI by the new period of capitalist decadence.

It is therefore on the basis of the critical reappraisal carried out by the ‘Fractions of the Communist Left' that the CI lives today, and will live in the World Communist Party of tomorrow.

Today, in the face of growing exploitation and poverty, the proletariat must adopt the same position as the Zimmerwald Left: No to the holy alliance with the bourgeoisie in the economic war! No to sacrifices to save the national economy! Long live the class struggle! Transform the economic war into a civil war!

In the face of economic catastrophe, in the face of social decomposition, in the face of the perspective of a Third imperialist World War, the historic alternative is the same today as it was in 1919: the destruction of capitalism and the installation of the worldwide dictatorship of the proletariat, or the destruction of humanity. Socialism or barbarism.

The future belongs to communism.

RL

Historic events:

Development of proletarian consciousness and organisation:

Rubric:

Polemic: Class consciousness and the Party

- 2871 reads

Preliminary Introduction:

Of the various proletarian groups which the GPI has made contact and initiated an exchange of publications with, the IBRP (particularly the PCInt) has been one of those making a large and direct critique of our positions as expressed in Revolucion Mundial. We salute this attitude of the IBRP. There are various questions that we have taken up with these comrades, but all of them are centered around one main preoccupation; in the IBRP's judgment, the GPI has "adopted very quickly, and without hardly a critique, the positions of the ICC, which they characterize as being within the proletarian political camp." According to the IBRP, this is to be explained by the "direct and exclusive" contact with the ICC which marked the origins of the GPI, and "since we are convinced that the ICC (without denying it the merit of being an organization of sincere militants, loyal to the proletarian class) does not represent a valid pole of regroupment for the constitution of the international revolutionary party, we think that the comrades of the GPI must take further steps towards a real process of clarification, decantation and selection useful to the constitution of a revolutionary pole in Mexico ... a series of political discussions, the outcome of which will demonstrate that we were right."[1]

That the GPI has been fashioned under the influence of the ICC, taking up its positions from the beginning (or if you want to pose it from another perspective; that we are the result of the militant labor of the ICC), is something we've always pointed out. We have already said that presently, in front of the weakness of the international revolutionary milieu, before the creation of a unique pole of reference and regroupment of the revolutionary forces, new militants are emerging under the determined influence of this or that group, inheriting as many of their merits as deficiencies, are being immediately faced with the necessity of taking "a side" faced with the existing divergences in the milieu.

But it is not correct to say that the GPI has adopted the ICC's positions without being critical. From the beginning we have recognized the existence of a camp of proletarian political groups, in fact we want to say we do not consider the ICC as the possessor of "all that is true", and we have already had occasions to develop our divergences with them. Although, truth be told, from the understanding we have of the positions of the other regroupments, we have developed the conviction that the ICC is, at least, the one that has maintained the greatest political coherence.

We insist once more that the GPI considers that its consolidation will only be able to occur through the deepening of the political positions we have taken up, especially by confronting them with those maintained by the different groups of the international communist milieu. By being willing to discuss and to collaborate with other groups, as far as maintaining proletarian principles will permit, we situate ourselves as a small part of the process towards the confirmation of the world communist party.

In this spirit, we publish the position we have taken concerning the conception of the IBRP on class consciousness and the role of the party.

We understand that the conditions for the regroupmerrt of revolutionaries in a new international party are still far away and that much remains to be done; probably only some very important confrontations in the class struggle will permit a clear and effective polarization of revolutionary forces. We don't pretend to know the concrete form of this process of polarization. However it is certain that the necessity of a world communist party on a world scale will be posed each time with more urgency by the proletariat, and its present revolutionary minorities must make every effort to clear the way that leads to its constitution, laying the foundations so that the different existing groups will be able to regroup with the maximum political clarity possible. Beginning by clarifying the points of accord and divergences that exist on the role of the communist party in the working class.

Clearly, the GPI has no other choice than to "meddle" in the fundamental debates that have occupied revolutionaries for many years (and which recently have found expression in two important moments; firstly the conferences called by the PCInt and secondly the responses to the ‘International Proposal' of 1986 by Emancipacion Obrera. And if we have entered into debate with the comrades of the PCInt, it is because all of the points raised in the discussions by them refer to the question of class consciousness and the party. So, it is not for us to pretend to give right now a solution to the question. But if we can at least make clear what for us are the weaknesses of the IBRP (and of those who share its positions), we will consider the object of our article to have been fulfilled.

We criticize basically the PCInt's article ‘Class Consciousness in the Marxist Perspective', the Platform of the IBRP and their correspondence with us.

I. Posing the problem

In the article ‘Class Consciousness in the Marxist Perspective', the IBRP develop their conception of this question, endeavoring at the same time to demonstrate that in the polemic that took place between Lenin and Rosa Luxembourg concerning the formation of class consciousness and the role of the party, that the former was right and the latter (together with her present-day ‘inheritors'), were wrong.

There is in effect in the revolutionary milieu a tendency to present divergences on the party (and on all questions) as a reproduction or continuation of all the old debates that have always animated revolutionaries. This is the result not of an academic excess, but of a real effort of the proletarian political regroupments to take hold of the historical traditions of revolutionary positions.

But without doubt, it is obvious that the present debates cannot be exactly the same as those which took place almost a century ago: ‘much water has passed under the bridge' since then the proletariat has not only lived through the revolutionary wave, the largest ever known, but also the longest period of counter-revolution. For the present revolutionary minorities, there is an immense accumulation of experience that provides the basis for the clarification of problems that will be posed to the proletariat in its struggle, but at the same time they have greater difficulty obtaining this clarification due to their precarious existence.

And this, the present debate between revolutionaries concerning the relationship between class consciousness and the party, that apparently reproduces the same divergences between the tendencies represented by Lenin and Rosa Luxembourg, hides a much more profound divergence, more serious than the differences of these leaders of the proletariat.

In effect, whereas at the beginning of the century the preoccupation of those revolutionaries was to set out the process through which the proletarian masses arrive at class consciousness, that is to say, the understanding of the irreconcilable antagonism between the bourgeoisie and the proletariat, as well as the necessity and possibility of the communist revolution, now this preoccupation, although still present, is intersected by another more general and elemental, if you want, more ‘primitive' whether in general the proletarian masses can or cannot arrive - in some way - at class consciousness.

Whereas one part of the present revolutionary milieu, including the IBRP, consider that "the communist party is the only or principal depository of class consciousness," until the destruction of the bourgeois state and the establishment of the dictatorship of the proletariat, and only after then will the masses become class conscious.

The other part, in which the GPI includes itself, considers that the fundamental prerequisite for the destruction of the bourgeois state and the establishment of the dictatorship of the proletariat is the arrival of the proletariat, the determined mass of the class (at least the majority of the proletariat of the biggest cities) to class consciousness.

With the result that there exists a veritable abyss between the conceptions that are held on the role of the party (more specifically on the present role that the organized revolutionary minorities must fulfill). In the end, the debate does not consist of the more or less decisive role that the party will play in the process of the confirmation of the proletariat as a class for itself; the major problem is not to define whether the party ‘orients' or ‘leads', but a more basic question: what is meant by a class for itself?

Thus for example, perhaps we would be able to agree that the function of the party is ‘to lead' the proletariat. But this agreement would only be more apparent than real: since at present others (like the IBRP) consider ‘idealistic' the notion that the proletarian masses develop revolutionary consciousness as a condition for the taking of power, it's evident that because of this they have to see their relationship as essentially identical to that which, for example, exists between officers and soldiers in modern armies, or between the boss and the workers in the factory: that is to say, a relationship in which only the leader knows the real aims to follow, whereas for the led, these aims appear behind ideological clouds and, therefore, they have to be pushed along an imposed direction (in a patriarchal and authoritarian way), a relationship of the dominating to the dominated.

For us, on the contrary, the direction given by the communist party is nothing other than the comprehension, the profound conviction that develops in the whole of the working class, of the correctness of the party's programmatic positions and of its slogans, which are the expression of the class' own movement. A conviction at which the masses will arrive through learning the historical lessons that they extract from their struggle, in which the party participates taking a vanguard role. Between the party and the proletariat there is a relationship of a new type, the sole property of the working class.

So then, for some, the constitution of the proletariat into a class means that the party, unique bearer of the proletarian/revolutionary consciousness, comes to the head of the masses, who - despite all their experience of struggle are permanently dominated by bourgeois ideology. For others, on the contrary, the constitution of the proletariat as a class means that the masses, through their experience, and the intervention of the party, advance towards revolutionary proletarian consciousness. The IBRP hold the first position, we the second; perhaps the GPI will be submerged in idealism?

II. The IBRP intend to deepen Lenin

One of the first questions that arises from the article cited by the IBRP, is the new formulation that they make of the thesis that Lenin expressed in his work, What is to be done? But the changes the comrades introduce into the terminology employed by Lenin, do not signify so much a ‘precision' of his thought, but a travesty of it, behind which is found the displacement of the debate on the question concerning how the masses arrive at class consciousness, to whether in general it is possible for them to arrive at this. Therefore, though we do not share the thinking of Lenin according to which consciousness is introduced from outside the working class, before ‘criticizing' Lenin we must ‘defend' him, trying to restore his thinking, showing clearly what his preoccupations were and their role in the combat against the economists. (In order that there is no misunderstanding, we want to make it clear that when we refer to ‘Lenin', or to any other revolutionary, we do not look to see if they were ‘mistaken' or ‘infalable' as individuals, but we take them as representatives of a particular political current, and it is because in this or that work that this current which we want to take as our ‘example' is expressed more clearly).

OK. Lenin called trade union consciousness "the conviction that it is necessary to regroup in trade unions, to struggle against the bosses, to demand of the government the promulgation of this or that law necessary for the workers ..."[2] and social democratic consciousness (we today would call it communist consciousness) "the consciousness of the irreconcilable antagonisms between its interests (of the workers) and all contemporary political and social regimes"[3]. According to Lenin, the working class, despite its spontaneous struggles of resistance, is only capable of reaching a trade unionist consciousness, whereas communist consciousness has to be introduced from outside by the party.

The IBRP modify the formulation of Lenin, posing that "the immediate experience of the working class allows it to develop consciousness of its class identity and of the necessity of collective struggle ( ... )," that "the conditions of existence of the proletariat, its struggles and reflections on that struggle, raise its understanding to a level where it can see itself as a separate class, and define itself as by the need for struggle against the bourgeoisie. But class identity is not consciousness"[4]. And a little further on they say: "for class identity to be transformed into class consciousness, the organization of the proletariat into a class, hence into a political party is necessary." From this, we can see more clearly what the IBRP comrades mean when they talk of "transformation". Firstly it is necessary to note that what the comrades call "consciousness of class identity", Lenin called "trade union consciousness."

Moreover, Lenin made clear that the spontaneous element is the embryonic form of consciousness, "since there can be no talk of an independent ideology formulated by the working masses themselves in the course of their movement, the only choice is either socialist or bourgeois ideology... the spontaneous development of the working class movement leads to its subordination to bourgeois ideology... Therefore our task consists in combating spontaneity, it consists in separating the workers movement from this spontaneous tendency to trade unionism sheltering under the wing of the bourgeoisie and pulling towards the wing of revolutionary social democracy" (the then proletarian party)[5].

Now, it would be possible to ask on what side does the IBRP place this "consciousness of class identity" that the workers will develop? And they would answer: "For the most part, the experiences gained by the working class in its conflict with the bourgeoisie are structured by the world outlook of the bourgeoisie and give rise only to a sense of class identity which remains a type of bourgeois consciousness"[6].

So then, in a roundabout way, (changing ‘consciousness' for ‘sense'), the IBRP say that consciousness of working class identity is a form of bourgeois consciousness. We regret that this, straight away, is no more than the introduction of an enormous confusion of terms in marxism. But we have hardly begun; now the IBRP has to explain how class identity, that is to say this form of bourgeois consciousness, "is transformed into communist consciousness.":

"a section of the bourgeoisie goes over to the proletariat, and in particular, a portion of the bourgeois ideologists who have raised themselves to comprehending theoretically the historical movement as a whole (Communist Manifesto). Here, in a nutshell, is the materialist conception of class consciousness. The spontaneous struggle of the working class can raised the consciousness of that class to the level of class identity, the realization that it is not part of the ‘people', but is a class-in-itself. This is a necessary prelude to its qualitative leap to class consciousness (or, the emergence of the class for itself), but the latter can only come about if ‘philosophy' or a theoretical understanding of the historical movement as a whole is provided and grips the working class: ie if the class can become aware that it must be furnished with a party possessing a scientific world view. This world view is of necessity formulated outside of (though its material is partly furnished by) the class struggle and outside the existence of the whole proletariat, though individual proletarians participate in its creation" [P16, RP21][7]

There are expressed in this paragraph of the IBRP such a quantity of confusions that it is very difficult for us to know where to begin. We are trying to disentangle their reasoning. The IBRP offer us here three ‘levels' of consciousness.

The first level: consciousness of class identity which already is not considered as an identity of a class in opposition to the bosses, but only "that it is not part of the people." With this, the IBRP reduce this "embryonic consciousness," the product of the struggle about which Lenin talks, to the level of vulgar "knowledge", on the same level of understanding as a child which can make a verbal distinction between workers, peasants, etc. But the IBRP also denotes this identity as an indispensable premise in order that the leap towards class consciousness can occur. Without a doubt, the IBRP would say to us that this "class identity" is nothing other than a form of bourgeois consciousness - with the result that bourgeois consciousness is an indispensable premise for ... proletarian consciousness. In other words, in order for the proletariat to become a "class for itself", it must be a class "in itself", or, in order for the proletariat to become class conscious, it must go through an indispensable process which it does not have.

The second level: class consciousness. By means of a qualitative leap, the proletariat confirms itself as a class for itself. What does this leap consist of? In the conviction of the masses of the need of a party bearing - in itself - communist consciousness. But this conviction, does it imply that the proletarian masses break, in the end, with bourgeois ideology? According to the reasoning of the IBRP, no. The masses are not able to arrive at communist consciousness before the taking of power, and as there is no "middle way", then in reality there is no such qualitative leap.

The proletariat, according to the IBRP, confirms itself as a class for itself, but the proletariat remains dominated by bourgeois ideology. It would be fruitful to ask, what is the basis for the masses to become "convinced" of the necessity for the communist party, since nothing exists, apart from bourgeois ideology? How do the masses recognize the "correct" party, given that they are permanently dominated by bourgeois ideology and, therefore, they cannot understand the party's revolutionary positions? Such a "conviction" becomes a mere causality, something that depends, not on the correctness of the party's positions, but on its skillful maneuvers in relation to the other parties (bourgeois and petty bourgeois) who also try and "convince" the masses. The IBRP reduce the confirmation of the proletariat as a class for itself, to this.

The third level: communist consciousness, the theoretical understanding of the movement, the global, scientific understanding held by the party. Where does it come from? According to Marx: "The theoretical conclusions of the communists are in no way based on ideas or principles that have been invented, or discovered, by this or that would-be universal reformer. They merely express, in general terms, actual relations springing from an existing class struggle, from an historical movement going on under our eyes," (Communist Manifesto). But now the IBRP, "deepening" Lenin, have discovered that the theoretical thesis of communists are found in analyses elaborated outside of the class struggle (though this is part of its. material) by this or that bourgeois ideologist or this or that isolated proletarian that has risen to the level of ideologist. Very good, but the class struggle is the real form of the class existence, its prowess, its form of movement: the class does not exist but in its struggle. To affirm therefore, as the IBRP does, that communist consciousness is developed outside of the class struggle is the equivalent of saying that it is elaborated outside of classes, independently outside of these, and particularly outside of the proletariat. And, the effect of this reasoning is that the IBRP tend to differentiate between what will be the class consciousness of the proletariat (the consciousness of the necessity for the party) and what will be communist consciousness, making of the latter some sort of... "philosophy", inaccessible to the profane.

Certainly, we can find in the article of the IBRP paragraphs which contradict this, as when they say "to provide such a world view is the task of the communist party. It does this through a profound study of social reality, its conflicting processes and its historical trajectory coupled with political intervention in the class struggle. It thus aims to fuse all the sparks of communist consciousness generated in the class struggle into a coherent world view and to regroup all those who accept this world view into a force capable of intervention, capable of structuring the experience of the working class within the communist framework" [pI6, RP21][8]. Formulating the question like this, there nothing to suggest or support the conception of ideologists outside of the class struggle forging communist consciousness. But it is not us, but the IBRP that has to choose between the two contradictory positions.

What then does the deepening of Lenin by the IBRP consist of?

According to Lenin, the proletarian masses cannot by themselves - despite all their spontaneous struggle rise up to communist consciousness. Therefore, the party must infuse this consciousness, bring it to them, while he maintained that "the socialist consciousness of the worker masses is the only basis that can assure our triumph". "The party must always have the possibility to reveal to the working class the hostile antagonisms between its interests and those of the bourgeoisie." The consciousness attained by the party "must be infused into the working masses with an increasing fervor". If there are workers involved in the elaboration of socialist theory, "they only participate to the degree that they have attained, with greater or lesser perfection, a grasp of the science of their century, to advance this science. And in order that the workers attain this more frequently, it is necessary to concern oneself as much as possible with the development of the consciousness of the workers in general" [The IBRP who cite this first idea of Lenin have forgotten to cite the second].

The task of the party is to "use the sparks of political consciousness that the economic struggle generates in the spirit of the workers to raise them to the level of social democratic consciousness" (that is to say, communist). That the "the political consciousness of the class cannot be brought to the workers from outside of the sphere of the relationship between the workers and bosses. The only sphere in which it is possible to find the knowledge of the relations between all classes." That the communist militant will participate in the "integral development of the political consciousness of the proletariat." That "social democracy is always in the front line ... bringing abundant material for the development of political consciousness and the political activity of the proletariat." In the end the party must always concern itself with "general and multiple agitations and in general uniting all the labors that bring together as one the spontaneous destructive force of the multitude and the conscious destructive force of revolutionaries."

Whereas on the contrary, the IBRP consider that "to admit that the whole class or the majority of the working class, taking account of the domination of capital, can attain communist consciousness before the taking of power and the establishment of the dictatorship of the proletariat, is purely and simply idealism".

Sooner or later the comrades will have to extend their critique beyond Rosa Luxemburg and her "heirs." Extend it to Engels who, when he attacks the "social democratic cretinism", states:

"The time of revolutions carried through by small conscious minorities at the head of unconscious masses is past. Where it is a question of the complete social order, the masses themselves must also be in it, must have grasped what is at stake, what they are going for body and soul," (Introduction to the Class Struggle in France, 1895). Formulations of this type imply - according to the IBRP - "an over-estimation of how extensively true consciousness, not a product of the direct class experience, could eventually permeate the proletariat, via the party" [p 17, RP21][9].

But then the IBRP will have to extend its critique, we would say, to Lenin, and to see him as "over-estimating" the level of communist consciousness that the proletariat can develop, "over-estimating" the importance of the party's work in raising this consciousness as its fundamental and basic task, and for believing that the communist consciousness of the masses will be the only guarantee of the triumph of the revolution.

The whole of Lenin's combat in What is To Be Done? was directed against the economists, against those who objectively kept the workers at the level of trade unionism, in a spontaneity that pushed towards maintaining the workers under the domination of bourgeois ideology. And here is the IBRP, supposedly combating the "spontaneists", but instead of analysing how the masses develop consciousness, on the contrary establishing in theory the maintenance of the masses under the domination of bourgeois ideology. The comrades haven't deepened Lenin when they say that until the taking of power, the proletariat has no alternative but to convince themselves of the necessity for the party - which itself - bares communist consciousness. On the contrary, this is more like the thesis of the "economists": "that the workers are trapped in the trade unionist struggle and that leaves to the marxist intellectuals the political struggle."

For Lenin, the confirmation of the proletariat as a class for itself was signified by the raising of the masses to communist consciousness, uniting thus the whole spontaneous movement with scientific socialism. For the IBRP, on the contrary, the confirmation of the proletariat as a class for itself is signified by the maintenance of the masses under the domination of bourgeois ideology, the fusion of all bourgeois ideology with communist consciousness. This is what they reduce their "dialectic" to.

In the next Revolucion Mondial, we will continue this work dealing with the fundamentals of marxism concerning class consciousness and the role of the party.

October 1988

Ldo

[1] Letter of IBRP to the GPI, 19.3.88.

[2] What is To Be Done. Ed Anteo, p. 69.

[3] Opcit, p. 68

[4] ‘Class Consciousness In the Marxist Perspective', Communist Review No 2.

[5] What is To Be Done p81

[6] ‘Class Consciousness...' p10

[7] idem

[8] idem

[9] ‘Class Consciousness..." p15.

Life of the ICC:

Heritage of the Communist Left:

Recent and ongoing:

- Polemic [7]

The decomposition of capitalist society

- 2965 reads

Capitalism is in a dead-end; each day that passes presents us with a picture of a society heading for destruction. Since the holocaust of World War II, wars and massacres have continued non-stop on the capitalist periphery; the barbarity of this decadent system, whose prolonged death-agony can only provoke one endless round of destruction, is being laid bare day by day. The recent series of ‘natural' catastrophes and accidents, the increase in gangsterism, terrorism, drug-taking and drug smuggling are so many signs of the generalized gangrene that is eating away at the capitalist body politic all over the world.

Although capitalism's entry into its decadent period was the precondition for its overthrow by the proletarian revolution, the perpetuation of this decadence is not without danger for the working class. The spread of capitalism's putrefaction to every layer of society threatens to contaminate the only class that bears within it a future for humanity. This is why, as capitalism rots where it stands, it is up to revolutionaries not to console the working class with its misery and suffering by hiding the horror of this world in decomposition, but on the contrary to emphasize its full extent and to warn workers against this daily threat of contamination.

The announcement of catastrophes provoked by ‘natural' phenomena or by accidents, killing or mutilating a multitude of human beings, has become part of everyday life. In recent months, hardly a week has passed without the media displaying apocalyptic images of catastrophes that strike one day the under-developed countries, the next the great industrial metropoles of the Western world. Such events are becoming banal; they affect the entire planet. Not only do they increase the general insecurity of existence for the working class, as for the population in general; they are more and more felt as a menace threatening to engulf the entire human race in much the same way as a nuclear war.

As it plunges into decadence, capitalism can only create more destruction

Torrential rain in Bangladesh, hitting more than 30 million people in September 1988; the recent years' drought in the Sahel which has caused famines such as humanity has never seen before; hurricanes in the Carribean or over the island of Reunion, flattening the houses of the local population; earthquake in Armenia, destroying whole towns in a matter of minutes and burying tens of thousands of human beings in the ruins.... All these gigantic catastrophes which have ravaged under-developed countries in recent months are not restricted to the 3rd World or the Eastern bloc. They are tending to spread to the most industrialized regions of the world, as we can see from the appalling succession of air and rail accidents which have claimed hundreds of victims at the heart of the great urban concentrations of Western Europe.

Contrary to what the bourgeoisie would like to make us believe, none of this destruction, this loss of human life, is due to some kind of ‘law of series', or to the ‘uncontrollable forces of nature'. The only aim of these ‘explanations', which the ruling class finds so convenient, is to relieve its system of any responsibility, to hide all its rottenness and barbarity. For the real cause behind all these tragedies, this incalculable human suffering is capitalism itself, and this appalling succession of ‘natural', ‘accidental' tragedies is nothing other than the most spectacular expression of a moribund society, a society that is falling apart at the seams.

These tragedies reveal in the full light of day the total bankruptcy of the capitalist mode of production, which since World War I has entered into its period of decadence. Following a period of prosperity where capital was able to develop the productive forces and social wealth to an immense degree by creating and unifying the world market, by extending its mode of production throughout the planet, this decadence means that since the beginning of the century capitalism has reached its own historic limits. Capitalism's decline today is expressed by the fact that it can no longer produce anything today but destruction and barbarity, famines and massacres, on a planetary scale.

This decadence explains in particular why the countries of the ‘Third World' have been unable to develop: they arrived too late on a world market that was already constituted, shared out and saturated (see our pamphlet The Decadence of Capitalism). This is what condemns these countries, despite all the hypocritical talk about their ‘development', to being the first victims of dying capitalism's utter barbarity.

The longer its death-agony lasts, the more horribly do capitalism's principal characteristics appear, as the system's insoluble internal contradictions burst into the open.

Obviously, we cannot accuse capitalism of causing earthquakes or hurricanes. It is responsible, however, for the fact that such natural phenomena are transformed into immense social disasters.

Capitalism possesses the technical ability to send men to the moon, to produce monstrous weapons capable of destroying the planet a dozen times over; at the same time it is incapable of protecting the population from natural disasters by building dams against the effects of hurricanes, or by building earthquake-resistant housing.

Worse still, not only can capitalism do nothing to forestall these catastrophes, it is equally incapable of alleviating their devastating effects. What the ruling class calls ‘international aid' to the affected populations is a disgusting lie. Every state and government of the ruling class is directly responsible for the suffering of hundreds of millions of human beings who die like flies every day, victims of cholera, dysentery and hunger.

While millions of children are threatened with death from starvation, in capitalism's great industrial centers millions of tons of milk are destroyed every year to prevent a collapse in the market price. In countries ravaged by monsoons or hurricanes, the population is reduced to fighting over a meager ration of grain, while the governments of the EEC plan to leave fallow 20% of farming land, in order to combat.... over-production!

Decadent capitalism's appalling barbarity is not only expressed in its impotence to relieve the suffering of the victims of natural disasters. The permanent and insoluble crisis of the systern is itself an immense catastrophe for the whole of humanity, as we can see from the increasing pauperization of millions of human beings reduced to a state of desperate wretchedness. Capitalism's inability to integrate the immense masses of unemployed into the productive process is not a problem limited to the ‘Third World'. In the very heart of the most industrialized nations, millions of proletarians are being reduced to a state of abject poverty. In the richest state of the world, this transformation of immense masses of workers into down-and-outs is particularly clear: in the United States, millions of workers, mostly full-time wage earners (representing 15% of the population living below the poverty line), are being made homeless and forced to sleep in the streets, in pornographic cinemas (the only ones to remain open all night) or in cars, because they cannot afford a place to live.

The more capitalism is stifled by its generalized crisis of over-production, the less is it able to overcome the famines in countries like Ethiopia or the Sudan which today are turning into veritable genocides. The more it masters technology, the less it uses it for the good of the population.

In the face of this appalling reality, what use are all these ‘humanitarian' campaigns for ‘aid to the victims and/or the starving', all the appeals for ‘solidarity' launched by 57 varieties of media stars? How ‘effective' are all these charitable organizations, which in the advanced countries run soup kitchens or overnight hostels for the homeless? What is the meaning of all these wretched subsidies that some states distribute to those who are destitute? At best, all such ‘aid' put together is only a drop in an ocean of poverty and famine. In the Third World, they only put off the tragic deadline for a few weeks; they just manage to prevent the advanced countries from looking too much like the Third World. In fact, all this ‘aid', these ‘solidarity campaigns' are nothing but sinister masquerades, a sordid and cynical racket, whose real ‘effectiveness' is measured in their ability to buy consciences and hide the barbarism and absurdity of the world in which we live.

The better feelings of bourgeois humanism have their limits. Despite the crocodile tears of clergymen and other ‘charitable souls', despite the ‘willingness' of governments to help, these limits are dictated by the fact that the bourgeoisie cannot escape the laws of its own system. This is even more evident today when, after three quarters of a century of decadence, these laws are getting completely out of control, as can be seen in the series of catastrophic accidents in the industrialized countries.

In recent months, the proliferation of railway accidents, especially in the urban networks of advanced countries like France or Britain, has demonstrated that insecurity does not only threaten the populations of under-developed countries, but hangs over the entire world, in every aspect of daily life.

And, contrary to the lies peddled by the bourgeoisie, railways accidents like those at the Gare de Lyon in Paris (June 88), or Clapham Junction in south London (December 88) are not caused by human error, any more than mere bad economic management lies at the root of the present dilapidated state of the productive apparatus, or of the decaying public transportation which daily kill or mutilate hundreds of human beings in the most industrialized countries.

This series of accidents is nothing other than the disastrous result of every bourgeois state's policy of ‘rationalizing' production; in their insatiable quest for profit and competitivity in the face of a worsening world economic crisis, no saving that can be made by eroding the security of workers and of the population in general is too small to be worthwhile, whatever the cost in human lives. This ‘rationalization', which in the name of productivity is engaged in a more and more widespread destruction of productive forces, is in fact completely irrational. Labor power is being destroyed, not only through unemployment but in the deaths and injuries provoked by the catastrophes and accidents at work caused by this same ‘rationalization'. Technical resources are being destroyed as factories are closed, but also by the material damage caused by all these ‘accidents'.

Similarly, all the disasters that the ecologists blame on ‘technical progress' the growing pollution of air and water, ‘accidents' in chemical plants such as Seveso in Italy or Bhopal in India which caused more than 2,500 deaths, nuclear catastrophes as at Three Mile Island or Chernobyl, the oil slicks that regularly destroy coastal plant and animal life thus endangering the ocean's food chain for decades to come (as we have seen lately in the Antarctic), the destruction by CFC's of the ozone layer that protects every living thing from ultra-violet radiation, the rapid disappearance of the Amazon rain-forest, the planet's main source of oxygen - are nothing other than signs of decadent capitalism's irrational, suicidal logic, of its total inability to master the productive forces that it has set in motion, and which now threaten to upset for centuries to come, if not definitively, the planetary equilibrium necessary to the survival of the human species.

And this suicidal logic, the infernal machine of decadent capitalism, takes on still more terrifying proportions with the massive production of ever more sophisticated engines of death. All today's most advanced technology is today oriented towards arms production, in the perspective of massacres infinitely more murderous than those unleashed today (in ‘peace' time) in the countries of capitalism's periphery. There is no limit to the horror of this bloody monster that is decadent capitalism.

But all this destruction is only the tip of the iceberg, the visible signs of a more general phenomenon affecting every aspect of capitalist society. It is the reality of a world that is falling apart.

The ideological decomposition of capitalist society

This decomposition is not limited solely to the fact that despite all the development of its technology, capitalism is still subject to the laws of nature, or to its inability to master the means that it has set in motion for its own development. It affects not only the system's economic foundations, but every aspect of social life through the ideological decomposition of the ruling class' values which, as they collapse, drag with them every value that makes life in society possible, and in particular through an increasing atomization of the individual.

This decomposition of bourgeois values is not a new phenomenon. It was already marked during the 1960s by the emergence of marginal ideologies, which at the time could still offer an illusory hope of creating islands of a different society, based on other social relationships, within capitalism.

This decomposition of ruling class values was expressed in the appearance of the ‘community' type ideologies - the fruit of the revolt of petty bourgeois strata already hit by the crisis, and especially by the decomposition of society - and of the hippy movement of the 60s and early 70s, as well as by a whole series of currents advocating a ‘return to the earth', the ‘natural life', etc. Basing their existence on a supposedly ‘radical', contestationist critique of wage labor, commodities, money, private property, the family, ‘consumer society', etc, all these communities set themselves up as ‘alternative' or ‘revolutionary' solutions to the collapse of bourgeois values and the atomization of the individual. All justified themselves on the grounds that a better world could be built simply by ‘changing mentalities' and proliferating community experiments. However, all these minority ideologies (built on sand, since they were born of social strata which, unlike the proletariat, have no historical future), did not just peddle what their subsequent collapse has since proved to be mere illusion. In reality, their project was nothing other than a grotesque parody of primitive communism. This nostalgia for the past was merely an expression of a perfectly reactionary ideology, whose essentially religious basis is moreover revealed by the fact that all these ‘purifying' themes were taken up almost to the letter by mystic sects such as the ‘Moonies', Hare Krishna, ‘Children of God' and the like, which have arisen since from the ruins of these communities.

Today, the communities of the 60s and 70s have given way either to religious sects (for the most part exploited if not directly manipulated by the capitalist state and the great powers' secret police), or to still more ephemeral phenomena such as the huge gatherings at rock concerts organized by bourgeois institutions like ‘SOS Racisme' in France, ‘Band Aid' or Amnesty International; in the name of great humanitarian causes (the struggle against apartheid or world hunger), such gatherings have nothing better to offer the new generations than an ersatz of community and human solidarity.

But for several years now, capitalist society's ideological decomposition has been expressed above all by the development in the very heart of the great capitalist industrial metropoles, of nihilist ideologies of the ‘punk' variety, which express the void into which all society is increasingly thrust.

Today, such is the misery and barbarism engendered by the complete dead-end of the capitalist economy that the whole of society is more and more being stamped in the image of a world without any future, on the brink of an abyss. It is the realization of this dead-end since the beginning of the 80s that has wiped out all the ‘alternative solutions' of the communities of the previous two decades. The hippy communities' utopia of ‘peace and love' has been succeeded by the ‘no future' of the punk and skinhead gangs that terrorize the inner cities. The love, pacifism, and beatific non-violence of the previous years' marginal communities has been followed by the violence, the hatred, and the urge to destroy that animates a marginalized youth, left to itself in a world without hope, a world which has nothing to offer but unemployment and misery.