International Review no.20 1st quarter 1980

- 2950 reads

v

The 80s: years of truth

- 2856 reads

History does not obey the dates on a calendar and yet decades often become symbols for specific historical events. The thirties bring to mind the depression which hit capitalism fifty years ago; the forties, the war which destroyed the equivalent of a country life France or Italy. On the threshold of the eighties, how can we characterize the decade just ending and what will be the major phenomena of the new one just beginning?

The crisis? The crisis certainly made its mark on the 1970s but it will mark the 1980s even more. Between the sixties and the seventies there was a real change in the economic situation of the world: the sixties were the last years of the reconstruction period when the dying fires of an artificial ‘prosperity’ still burned; artificial because this ‘prosperity’ was based on the ephemeral mechanisms of the reconstitution of the industrial and commercial potential of Europe and Japan destroyed during the war. Once this potential was realized capitalism found itself once again facing its fatal impasse: the saturation of markets; that is why the sixties ended in ‘prosperity’ and the seventies in paralysis. But there will be no difference of this sort between the seventies and the eighties except that economic stagnation will be even worse.

Slaughter and suffering? The coming years promise to be particularly ‘rich’ in this domain. Never before has there been so much famine, so much genocide in the world. With all the ‘liberation’ of peoples, with all the aid given to them mostly in the form of war machines, the great powers will soon have erased them from the map. This apocalypse is not new, but in the coming decade with the deepening of the crisis, there will be more and more Cambodias despite all the petitions and humanitarian campaigns. Cambodia is simply a more terrifying example of the horrors which have followed in an unbroken line since World War II and which have plunged a large part of humanity into total hell. In this sense the eighties will be ravaged by the same specter of genocide as the seventies.

However recent events show very important changes developing in the very depths of society; these changes are less to do with the economic infrastructure or the degree of misery and poverty than with the behavior of the major classes: the bourgeoisie and the proletariat.

In a sense the seventies were the years of illusion. In the major centers of capitalism, the bourgeoisie and the proletariat came up against the stark reality of the crisis, often in a very brutal way. But at the same time, and particularly in the more advanced countries, these two classes which decide the fate of the world have had a tendency to blind themselves to this reality: the bourgeoisie because it finds it unbearable to face the historical bankruptcy of its system and the proletariat partly because it suffers from the illusions of bourgeois ideology and partly because it is not easy for the proletariat to understand and shoulder the crushing historic responsibilities which the crisis and the understanding of its implications place on the shoulders of the revolutionary class. For years now the bourgeoisie has been grasping at straws trying to prove that the crisis can have a solution. And it is true that since 1967 the regularly recurrent recessions (1967, 1970-71, 1974-75) accompanied by chronic inflation have been followed by a ‘recovery’. The recovery of 1972-73 led to the highest expansion rates since the war (particularly in the US). Although there were waves of galloping inflation, certain government deflationary policies were (at least, somewhat) effective in keeping inflation to less than 5 per cent a year. The bourgeoisie had only to keep applying these policies and all would be well. Obviously the bourgeoisie began to realize that these reflationary policies just reflated inflation and that the deflationary policies led to recession. But even if things were not going as well as they used to, the bourgeoisie could not give up the idea that it could just continue to cut away the dead weight of the economy, to impose austerity and unemployment and one day business would be back to normal.

Today the bourgeoisie has abandoned this illusion. After the failure of all the remedies administered to the economy (see the article ‘The Acceleration of the Crisis’ in this issue) which have only managed to poison it, the bourgeoisie has discovered in a muffled but painful way that there is no solution to the crisis. Recognizing the impasse, there is nothing left but a leap in the dark. And for the bourgeoisie a leap in the dark is war.

This march towards war is nothing new; in fact since the end of World War II capitalism has never really disarmed as it at least partially did after the first war. And since the end of the sixties when capitalism experienced once again a decline in its economic situation, inter-imperialist tensions have increased and armaments have grown phenomenally. Today a million dollars a minute are being poured into the production of the means of destruction and death. Up to now the bourgeoisie has been following the path to war in a more or less conscious way. The objective needs of its economy have been pushing it towards war but the bourgeoisie has not really been aware that war is indeed the only perspective its system can offer to humanity. The bourgeoisie is not fully aware of the fact that its inability to mobilize the proletariat for war constitutes the only serious obstacle barring the way.

Today with the total failure of the economy, the bourgeoisie is slowly realizing its true situation and is acting on it. On the one hand it is arming to the teeth. Everywhere military budgets are skyrocketing. The already terrifying weapons at its disposal are being replaced by even more ‘efficient’ ones (‘Backfires’, Pershing 2s, neutron bombs, etc). But armaments are not the only field of its activity. As we pointed out in the ICC declaration on the Iran/USA crisis, the bourgeoisie has also undertaken a massive campaign to create an atmosphere of war psychosis in order to prepare public opinion for its increasingly war-like projects. Because war is on the cards and because people are not prepared for this perspective, all possible pretexts must be exploited to create ‘national unity’, ‘national pride’ and guide opinion away from sordid struggles of self-interest (meaning class struggle) towards the altruism of patriotism and the defense of civilization against the threatening forces of barbarism like Islamic fanaticism, Arab greed, totalitarianism or imperialism. This is the language the ruling class is using all over the world.

The bourgeoisie’s speeches to the working class are indeed changing. As long as it seemed as though the crisis could have a solution the bourgeoisie lulled the exploited with illusory promises: accept austerity today and everything will be better tomorrow. The left was very successful with these kinds of lies: the crisis is not the result of the insurmountable inner contradictions of the system itself, but simply a question of ‘bad management’ or ‘greedy monopolies’ or ‘multinationals’ -- voting for the left will change all this! But today this language does not work anymore. When the left was in power it did no better than the right and from the workers point of view, often worse. Since the promise of a ‘better tomorrow’ does not fool anyone anymore, the ruling class has changed its tune. The opposite is starting to be trumpeted now: the worst is ahead of us and there is nothing we can do, ‘the others are to blame’, there is no way out. The bourgeoisie is hoping in this way to create the national unity which Churchill obtained in other circumstances by offering the British population “blood, sweat, tears and toil”.

As the bourgeoisie loses its own illusions it is increasingly forced to speak clearly to the working class about the future. If the workers today were resigned and demoralized as they were in the thirties this language could be effective. Since we are going to have war anyway we might as well try to save what we can: ‘democracy’, the ‘land of my forefathers’, my ‘territory’; so we have to accept war and sacrifices. This is the response the ruling class would like us to make. But unhappily for them the new generations of workers do not have the resignation of their forebears. As soon as the crisis began to affect the workers, even before the crisis was recognized as such by anyone except tiny minorities of revolutionaries who had not forgotten the lessons of Marxism, the working class began to struggle. Its struggles at the end of the sixties and the beginning of the seventies showed by their broad scope and militant determination that the terrible counter-revolution which weighed on society since the crushing of the first revolutionary wave after World War I, was now over. It was no longer ‘midnight in the century’ and capitalism had to confront the proletariat once again -- that giant it thought had been safely put to sleep. But although the proletariat was full of vitality it lacked experience and it let itself be taken in by the traps the bourgeoisie set once it had recovered from shock. Relying on the fact that its crisis was developing at a slower pace than in the thirties, the bourgeoisie managed to communicate its own illusions about a ‘solution’ to the crisis to the workers. For several years the working class believed these stories about the ‘left alternative’ -- whether it was called the Labor government, popular power, the Programme Commun, the Social Contract, the Moncloa Pact or the historic compromise. Leaving aside open struggle for a while the workers let themselves be paraded around in electoral dead-ends adjusting themselves, almost without any reaction, to greater and greater doses of unemployment and austerity. But what the first wave of struggles in 1968 already showed is being confirmed again today: bourgeois mystifications do not have the force they used to have. After so much use the speeches on ‘the defense of democracy and civilization’ or on ‘the socialist fatherland’ wear out their impact. And the ‘national interest’, ‘terrorism’ or other ideological gadgets cannot replace them. As we say in our article ‘Our Intervention and its Critics’ (in this issue) the proletariat has once again taken up the path of struggle and obliged the left, if it was in government, to move into the opposition in order to accomplish its capitalist task by radicalizing its verbiage.

With a crisis whose effects weigh more and more heavily on the working class with each passing day, with the experience of a first wave of struggle and an awareness of the traps laid by the bourgeoisie to stop it, and with the very hesitant but real emergence of revolutionary minorities, the working class has returned to assert its force and its enormous reservoir of combativity. If the bourgeoisie has nothing but generalized war to give humanity as its future, the class struggles developing today prove that the proletariat is not ready to give the bourgeoisie free rein. The working class has another future to propose, a future of communism where there will be no wars, no exploitation.

In the decade beginning today, the historical alternative will be decided: either the proletariat will continue its offensive, continue to paralyze the murderous arm of capitalism in its death throes and gather its forces to destroy the system, or else it will let itself be trapped, worn out, demoralized by speeches and repression and then the way will be open for a new holocaust which risks the elimination of all human society.

If the seventies were years of illusion both for the bourgeoisie and the proletariat; because the reality of the world will be revealed in its true colors, because the future of humanity will in large part be decided, the eighties will be the years of truth.

Heritage of the Communist Left:

General and theoretical questions:

- Decomposition [2]

The acceleration of the crisis

- 2342 reads

The so-called ‘economic explanations’ that the ruling class soaks into the public mind through the press, radio and TV, almost always have one clear and avowed purpose: to justify in the name of ‘economic science’ the sacrifices which capital demands from those it exploits.

The ‘experts’ take the floor and quote their statistics only to ‘explain’ why we have to accept the growth of unemployment, resign ourselves to a decline in real wages, pay more taxes but still work harder; why immigrant workers have to be thrown out of the country -- in short, why we have to remain forever under the domination of the laws of capitalism even though these laws are leading humanity to ruin and despair.

To refuse these laws and to fight against them means rejecting the ‘economic’ justifications governments use to impose their system of exploitation. It is not enough to say: “It doesn’t matter what they say because it is all lies anyway”. The how and the why has to be understood if we want to be able to build something really different tomorrow.

The proletarian revolution is and must be a conscious revolution. The proletariat cannot rid humanity of the paralyzing obstacles of capitalism without knowing what they are. Understanding the economic situation of capitalism is essential to any conscious action in society because up to now humanity has been dominated by economic needs.

Under capitalism, as in all social systems in history, understanding the world is first of all understanding economic life. Understanding how to destroy capitalism is understanding how it is weakening, understanding its crises.

The aim of this article is to elucidate recent developments in the crisis and to clarify the perspectives. Its intention is to show that today’s aggravation of the crisis is the harbinger of a recession in the 1980s of unprecedented proportions since the end of World War II.

The article contains a considerable amount of statistics but these dry figures are necessary to an analysis of the crisis, to seeing where it is heading. The article uses ‘official’ statistics despite an awareness of their limitations. Economic statistics suffer from ideological as well as technical distortions. Because the so-called ‘economic science’ is part and parcel of the ideology and propaganda of the ruling class, statistics can always be manipulated to justify the defense and survival of the system. The ‘experts’ of the bourgeoisie do not necessarily do this with Machiavellian forethought: they themselves are the victims of the ideological poison they secrete. But it is not only a question of ideological distortions. The statistics also suffer from technical errors due to the decomposition of the economic system itself. In fact, the measurement used in most economic statistics is money, the dollar or another currency. But inflation and the increasingly violent convulsions of international exchange rates make monetary values less and less valid as measurements of real economic activity. This is particularly true for the measurement of economic aggregates in terms of volume (the volume of the gross national product, for example), that is, in terms of ‘constant money’, a theoretical abstraction of money which is not devalued by inflation.

But whatever the known faults of existing economic statistics, they are the only ones available. If they lack precision, they do, however, in one way or another, reflect the direction of major economic trends. In any case, using capitalism’s own statistics to demonstrate the bankruptcy of the system and the possibility of destroying it does not weaken the force of the arguments; on the contrary, it tends to strengthen it.

***********************

The world economy enters the 1980s sliding into a new recession, the fourth since 1967.

In the eastern bloc countries, growth rates have fallen to the lowest level since World War II (4 per cent growth in 1978).

The Secretariat of the OECD, an organization which groups the twenty-four most industrialized countries of the western bloc, announced a growth rate of 3% in 1979 for the whole of its zone and predicted a decline to 1.5% in 1980. This means a quasi-stagnation of economic activity.

The US and Great Britain are the first to slide into this new recession. The first and fifth greatest powers in the bloc -- which together account for 40% of the production of the OECD countries -- will have a negative growth in 1980. This means that the mass of production realized everyday will not only cease to grow but will actually diminish in absolute terms.

What will be the extent of this recession? How many countries will it affect? How long will it last? How deep will it be?

The recession gives indications of being the most geographically widespread since World War II: for the first time all regions of the planet will be simultaneously affected.

It risks being the longest lasting.

It will probably be the most profound in terms of the decline in growth and thus in terms of unemployment.

In other words, the workers of the entire world will experience the most brutal degradation of their living conditions since World War II. Millions more workers will be laid off in all countries, even those who seemed to be able to keep their head above water. Wages will be drastically cut by the combined effects of wage-freeze policies and inflation.

The last crumbs given by capitalism in the years of the relative prosperity of reconstruction are being taken back by capitalism ... and they will not think of offering them again. The various nations of this world are preparing to undergo another round of economic and social convulsions.

But what allow us to assert that the recession capitalism is sliding into will be the longest and the deepest since the war?

Three types of factors:

-- first of all, the broad scope of the present decline in the world economy;

-- secondly, the increasing inadequacy of the means at capitalism’s disposal to re-launch the economy;

-- thirdly, the growing impossibility for the different national governments to continue to use reflation policies.

In other words, the fatal disease of capitalism is passing through a phase of major decline; not only are the usual drugs administered by the different governments having less and less of an effect but the abusive use of these remedies have poisoned the patient. Like the doctors who frantically tried to keep the dying Franco ‘alive’, the bourgeoisie today is using desperate therapies even though they serve no scientific purpose!

Each of the three aspects mentioned will be further expanded in the article: the intensification of the present crisis on the one hand, and on the other the inadequacy of present methods available to induce recovery and the impossibility of increasing their scope without further accelerating the crisis.

The present deepening of the crisis

For the moment, among the major industrial countries of the western bloc the US and Great Britain are the hardest hits. Growth rates have declined most sharply in these countries in the course of 1979 as the following table shows:

|

Table I Rate of Growth Of the Gross National Product (Percentage of Variation) |

||

|

|

1978 |

1979 |

|

United States |

4.0 |

2.8 |

|

Great Britain |

3.2 |

1.3 |

|

Japan |

5.6 |

5.5 |

|

France |

3.3 |

3.0 |

|

Canada |

3.4 |

3.5 |

|

Italy |

2.6 |

4.3 |

|

Source: Economic Perspectives of the OECD, July 1979 |

But no-one has any illusions about the possibility of other countries of the bloc keeping up their growth rates for very long if the US goes into a recession because the economies of Japan and Europe are totally tied to their economic and military leader.

This dependency, which rests primarily on the absolute supremacy of the leader of the bloc within its sphere (and the same is true in the Russian bloc), has in fact increased since the beginning of the 1970s. By reducing the growth of their production, the US hopes to reduce their imports. But by reducing their buying power on the world market, they directly or indirectly limit outlets for European and Japanese production.

Contrary to the assertions of certain economists, present growth rates in Europe and Japan cannot be maintained to compensate for a collapse in the US. On the contrary, like in 1969, the fall in growth in the US is simply an immediate precursor of the fall in all other industrial countries.

The annual report of the Common Market Commission, which published its forecasts for the 1980s in October, has already announced a slowdown of 3.1% in growth for EEC countries in 1979 and 2% in 1980; an acceleration of inflation and an increase in unemployment from 5.6% to 6.2%, “the highest increase foreseen since the Commission began to establish its statistics in 1973” (Le Soir, Bruxelles).

At the end of 1979 lay-off announcements proliferated in all western countries. But the specificity of these announcements was that they concerned not only sectors already in difficulty, but also sectors which had been considered relatively safe from the effects of the crisis up to now. The lay-offs continue to grow in hard-hit sectors: the largest steel producer in the US, US Steel, has announced the closing of ten factories and lay-offs affecting 13,000 workers in Great Britain the British Steel Corporation intends to reduce its workforce by 50,000 workers.

But now it is also the motor industry and electronics, the sectors considered to be the ‘locomotives of the economy’ which are being hit. In the US, motor car production fell by 25% between December 1978 and December 1979. “One hundred thousand car workers (one out of every seven) are from now on indefinitely unemployed and forty thousand others are temporarily unemployed following one--or-two-week shutdowns in several states” (Le Monde, France). In Germany, whose economy is the envy of governments all over the world, car production fell 4% in a year. Opel had to put 16,000 on partial unemployment for two weeks and Ford-Germany 12,000 for twenty-five days. The vanguard sector, electronics, has just been hit by the collapse of the German company, AFG-Telefunken, which predicts 13,000 lay-offs.

In the underdeveloped countries, the economic crisis, which has long since plunged most of them into total economic atrophy, has now hit certain countries which used to be considered economic ‘miracles’. Whether we look at countries which experienced a relative industrial development in recent years like South Korea or Brazil, or oil-producing countries like Venezuela or Iran, these countries are now experiencing a violent degradation of their economic situation ... and along with this, the collapse of all the myths about their eventual ‘economic take-off’.

The eastern bloc countries too are experiencing a powerful exacerbation of their economic difficulties. Despite policies designed to reduce their debt to the west, these debts have only increased.

According to the UN Economic Commission for Europe, these debts have increased more than 17% in 1978 in relation to the previous year. If we turn to the internal situation, the investigation of the economic situation undertaken by Russian leaders for the Autumn 1979 Session of the Supreme Soviet drew a particularly somber balance sheet in such important areas as transportation, agricultural production and oil production. In the satellite countries, such as Poland, governments are beginning to speak officially of unemployment and especially inflation. Inflation, that disease which Stalinist dogma pretends to reserve only for western countries, is increasing on an unprecedented scale.

So much for the immediate situation. In itself, by the scope and rapidity of the economic decline, the situation can be seen as but the beginning of a new recession of which the worst is yet to come.

The techniques of ‘recovery’

I. The Growing Inadequacy of Reflation Techniques

One of the major characteristics of the economic evolution of the world, particularly in the west since the 1974-75 recession, is that contrary to what happened after the recessions of 1967 or 1970, reflation policies have brought more and more mediocre results, if any at all, despite all the considerable governmental efforts.

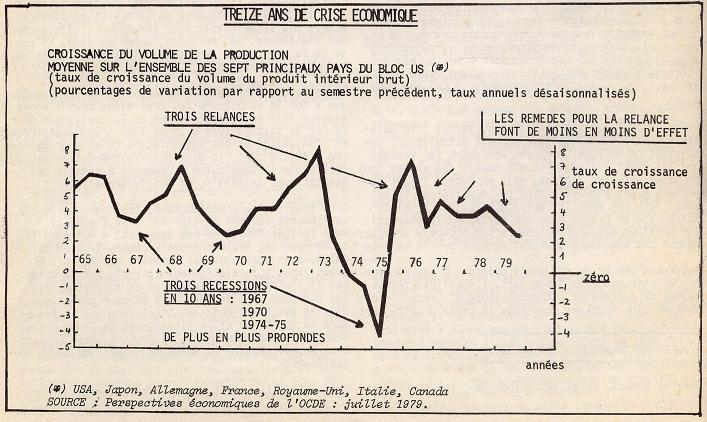

With the definitive end of the mechanisms of reconstruction in the mid-sixties, western capitalism has had to adapt itself to a life of perpetual downward swings whose scope is increasingly large and violent. Like an enraged animal striking its head against the bars of its cage, western capitalism has more and more violently come up against two dangers: on the one hand deeper and deeper recessions and on the other hand more and more difficult and inflationary recoveries. The graph below, which traces the evolution of the growth in production for the seven major powers of the western bloc (the US, Japan, West Germany, France, Great Britain, Italy and Canada) shows how these swings have been more and more drastic, ending in the striking failure of reflation policies from 1976 to 1979.

graph 1

The major stages of the crisis in the western economy since 1967 can be summarized as follows:

-- in 1967 slowdown in growth;

-- in 1968 recovery;

-- from 1969 to 1971 a new recession, deeper than 1967;

-- from 1972 to the middle of 1973 a second recovery breaking up the international monetary system with the devaluation of the dollar in 1971 and the floating of the major monetary parities; governments financed the general recovery with tons of new paper money;

-- at the beginning of 1973 the seven major powers had the highest growth rate in eighteen years (8 and a third as an annual base in the first half of 1973);

-- the end of 1973 to the end of 1975 a new recession, the third, the longest and deepest; in the second half of 1973 production increased at a rate of only 2% a year; more than a year later in early 1975 it regressed at more than a rate of 4.3% per year;

-- 1976-1979, third recovery; but this time despite recourse to the Keynesian policy of reflation through the creation of state budgetary deficits, despite the new market created by the OPEC countries which due to the rise in oil prices represented a strong demand for manufactured goods from the industrialized world1, despite the enormous deficit in the trade balance of the US which due to the international role of the dollar, created and maintained an artificial market by importing much more than it exported, despite all these methods put into place by governments, economic growth after the brief recovery in 1976 kept losing ground, slowly but surely.

Yet the doses of the remedies applied by the governments were particularly strong:

|

Table 2 Growth in the Volume of GNP (Percentage of annual variation) |

||||

|

|

1976 |

1977 |

1978 |

1979 |

|

The 7 great powers |

5.4 |

4.1 |

4.0 |

3.5 |

|

All 24 of the OECD countries |

5.1 |

4.1 |

4.0 |

3.5 |

|

Source: Economic Perspectives of the OECD, July 1979 |

Budget deficits: since 1975 the major industrial countries have had recourse to uninterrupted increases in state expenditures over and above that of revenues in order to create a demand capable of re-launching growth. This led to permanent budget deficits which reached levels equivalent to more than 5% of national production in some cases (5.8% for Germany in 1975; 5.4% for Japan in 1979) and went above 10% for weaker countries like Italy (11.7% in 1975; 11.5% in 1979). The average of these budget deficits for the five year period between 1975 and 1979 is in itself eloquent enough.

|

Table 3 Public Administration Deficits (As a percentage of GNP) Average 1975-1979 |

|

|

United States |

1.9 (a) |

|

Japan |

4.1 |

|

Germany |

4.7 |

|

France |

1.7 |

|

Great Britain |

4.3 |

|

Canada |

2.7 |

|

Italy |

10.2 |

|

Source: Idem (a) 1975-1978 |

The financing of growth in the bloc through the trade deficit of the US: by buying much more than they managed to sell, the US was an important factor in the growth of the economy of their bloc from 1976-79. In fact, since the conclusion of the reconstruction of Europe and Japan at the end of the sixties and with the war in Vietnam, the growth of the western bloc has, in part, been artificially financed by the trade deficit of the US. Because the US dollar serves as the medium of exchange and reserve on the world market, other countries are obliged to accept the artificial money of the US as payment.

Thus the recovery after the 1970 recession was ‘stimulated’ by two years of a particularly large US deficit. And after the 1974-75 recession, the US again had recourse to this policy to an unprecedented extent. In the last three years the US has increased its imports more rapidly than the other powers in its bloc as the following figures show:

|

Table 4 Increase in the Volume of Imports (Percentages of annual variation) Average 1977-1979 |

|

|

Unites States |

8.1 |

|

Japan |

6.6 |

|

Germany |

6.6 |

|

France |

5.3 |

|

Great Britain |

4.8 |

|

Italy |

5.5 |

|

Canada |

4.2 |

|

Source: Idem |

This policy led to a dizzying growth of the trade deficit of the US. This deficit momentarily allowed the other countries of its bloc to have positive trade balances.

|

Table 5 Current Trade Balance of the Major Countries of Western Bloc (in Billions of dollars, averages 1977-1979) |

|

|

United States |

-14.3 |

|

Japan |

+9.3 |

|

Germany |

+6.1 |

|

France |

+1.4 |

|

Great Britain |

+0.5 |

|

Italy |

+4.4 |

It is clear that both the ‘budget deficit’ remedy and the ‘US trade deficit’ remedy (“injecting dollars into the economy”) have been administered in massive doses over the past few years. The mediocrity of the results obtained proves only one thing: their effectiveness is steadily decreasing. And that is the second reason why we foresee an exceptionally deep recession for the beginning of the 1980s.

But there are even more serious reasons. Because governments have had such extensive recourse to these artificial stimulants in increasing doses, they have ended up by completely poisoning the body of their economies.

II. The Impossibility of Continuing to Use the Same Remedies

Among other economic shocks, the year 1979 was marked by the most spectacular monetary alert that the system has experienced since the war. While capitalism celebrated the fiftieth anniversary of the 1929 crash, the price of gold shot up to incredible heights. In several weeks the price of gold went over $400 an ounce. The alert was not simply an accident due to speculation. At the beginning of the seventies the official price of gold was S38 an ounce (after the first devaluation of the dollar in 1971). Nine years later ten times more greenbacks were needed for an ounce. But the price of gold has not just increased in dollar terms. It has shot up in terms of all currencies. This really means that the buying power of all currencies has drastically fallen.

The recent gold crisis represented nothing less than the real threat of a definitive collapse of the international monetary system, the threat of the disappearance of the tool which conditions all the economic transactions of capitalism from the buying of soap powder to the joint financing of a dam in a third world country.

The monetary crisis sanctions the impossibility not only of continuing to run capitalism through national and international monetary manipulations but in fact, the impossibility of even surviving in the endless spiral of inflation and monetary credits. The debt of the entire world economy has reached critical proportions in all spheres: the debts of third world countries which for years bought factories on credit without being able to find any markets for their products; the debts of eastern bloc countries which are continually growing without any hope of repayment. The debts of the US have flooded the world market with dollars (Eurodollars or petro-dollars); in recent years the US has experienced a wild acceleration of its domestic debts.

According to Business Week one of the most coherent spokesmen of big business in the US: “Since the end of 1975 the US has stimulated the economy through indebtedness and has provoked such a wild explosion of credit that it has left far behind even the fever which marked the beginning of the 1970s” (16 October, 1978). According to the same article from 1975-78 the debts of the state (government loans) have increased 47% reaching $825 billion in 1978, more than a third of the GNP of the country. This year’s debts of all economic agents (that is, companies, individuals, the government etc) has reached 3900 billion dollars, almost double the GNP! Faced with the growing impossibility of selling what it is able to produce, capitalism is increasingly living on indebtedness towards the future. Credit in all its forms has allowed it to put off facing the real, fundamental problems for a while. But this has not solved the problem, on the contrary, it has only aggravated it. By continuing to push payment deadlines forward, world capitalism has become highly fragile and unstable as the ‘gold crisis’ of Autumn 1979 proves.

Capitalism, at the beginning of the 80s, faces two alternatives: either to continue reflation policies in which case the monetary system will completely collapse, or to stop the artificial remedies and face recession.

The US government has already been forced to choose the latter ‘solution’ ... and so has made the choice for the entire world.

A false alternative for the workers

In this context all the governments in the world try to convince the workers that they must accept wage cuts and lay-offs so that ‘things can get better tomorrow’. 'Restructure our national economy and we'll make it’ is supposed to be the precondition for recovery.

Certainly market difficulties oblige national capitals to become as competitive as they can (and this implies lay-offs and wage-cuts). The few existing markets will go to those capitalists who manage to sell at the best price. But dying last is not escaping from death. All countries are facing the scarcity of markets; the world market is shrinking. And whatever the order in which countries fall, they will all fall.

The restructuration of the productive apparatus today is not a preparation for a new take-off, it is a preparation for death. Capitalism is not experiencing growing pains but the death rattle. For the workers, accepting sacrifices today will not solve the problems of tomorrow. The only thing they will gain is getting an even more brutal attack from capitalism later. Submitting to capitalism in its death throes is simply preparing the way for the only solution to its crises that capitalism has been able to find in sixty years: war. But resisting the attack now is in fact forging the will and the strength to destroy the old world and build a new one.

RV

1 According to the GATT’s 1978-79 annual report on international trade in 1978, underdeveloped countries absorbed 20% of the manufactured products exported by Western Europe and 46% of these products exported by Japan, largely on the basis of the revenues of the OPEC countries.

General and theoretical questions:

- Economics [3]

Workers’ combat and union maneuvers in Venezuela

- 2429 reads

The agitation and combativity that appeared during the negotiation of the last pay agreement in the textile industry have not disappeared. A general assembly, called by the textile union (SUTISS), ended by naming a ‘conflict committee’ at the regional level, with the aim of organizing a workers’ counter attack. That this committee was dominated by unionists of the PAD1 does not at all diminish the importance of the fact that a need was felt, however confusedly, for a combat organization distinct from the union apparatus. This is similar to the engineers’ demand for the presence at the negotiating table of a delegate elected by the general assembly. The ‘conflict committee’ put forward the idea of a regional strike for 17 October 1979. The union Federation was reticent at first, but finally gave way to the committee (even lending it their premises), and after a bit of diplomacy to try to get the CTV’s2 consent, a strike call was finally put out for Wednesday, 17 October. The CTV then began to talk about a national strike for 25 October. What was about to happen in Aragua was seen as a test which would determine the course of events to come.

“Follow Aragua’s Example!”3

The dawn of 17 October found Maracay (capital of the state of Aragua) paralyzed; in several outlying districts, all kinds of obstacles dumped in the streets interrupted the traffic. The workers arrived at their factories, and then made their way towards the Plaza Girardot in the town centre. The unions had distributed the strike call, but they intentionally remained silent about the time and place for the assembly. The union leadership wanted the strike to be a numerical success, but they were just as concerned that it should remain under their control. This explains why they put out the strike call, and why they kept a monopoly of information about the action that was planned. Nonetheless, the workers didn’t want to lose this opportunity to demonstrate their discontent, and accepted these conditions in their desire to unite in the street with their class brothers.

At 10am the Plaza was full of people. The vast majority was workers; a whole host of hastily-made banners were visible, indicating the presence of particular factories, demanding wage rises, or simply affirming a class viewpoint (for example, “they have the power because they want it”).

Then began the never-ending speeches, whose main lines were: the rise in prices, the need for wages to be adjusted, the government’s bad administration, the struggle against the Chambers of Commerce and Industry, and the preparation for the national strike.

In the crowd, you could feel that the workers interpreted the strike as well as the assembly as the beginning of a confrontation with the bourgeoisie and its state. Clearly, the mass of workers weren’t satisfied with listening passively, but wanted to express themselves as a collective body, which they could only do by marching through the streets. The pressure on the union leaders was so strong that they ended up by calling for a march down the Avenue Bolivar as far as the provincial Parliament, despite the fact that they had only planned on an assembly.

Beforehand, groups of young workers had patrolled the streets of the city centre, closing down all the shops (except the chemists’), with an attitude of determination to enforce the strike, but without any attempt at personal violence or individual aggression. In the same way, they intercepted buses and taxis, made the passengers get out and left the vehicles to go on their way without the slightest hindrance.

The demonstration gets out of control

The working class practically took possession of the streets of the city centre, it blocked the traffic, shut the shops, let its anger burst out, imposed its power. From this moment, events took on their own dynamic. The 10-15,000 demonstrators (the press talked of 30,000 probably because of the great fright the day gave them, for example, E Mendoza’s heart attack4, began to take up improvised slogans, especially insisting on ones that expressed their class feelings (“the discontented worker demands his rights”, “in shoes or sandals, the working class commands respect” were a couple of them). It was impossible to go back to the whining tones of the CTV’s explicit support for the wages law. The only figure put forward was for a 50% rise, but in general the demonstrators didn’t formulate precise ‘demands’; they expressed their rage and their will to struggle. There were frequent comments about the total uselessness of this famous law, about the beginning of the war of “poor against rich”. Near the Palace of Parliament there suddenly appeared a small detachment of the ‘forces of order’. Those at the front of the demonstration hurled themselves against it, and the police were obliged to run for shelter in the Palace, where they felt more protected. Immediately, the crowd concentrated before the entrance, which was obviously locked. The demonstration had not been prepared for this, and decided not to try to force an entry, but it fully felt the difference between ‘the people’ in the street and their ‘representatives’ barricaded in the Palace. Predictably, the union bureaucracy made every effort to pacify the demonstrators and to divert attention by calling for a return to the Plaza Girardot to close the day. After some hesitations, the cortege started off again, but instead of going straight to the Plaza Girardot, it preferred to make a tour of the ‘Legislative Palace’. Thus the workers marked out the places they would have to occupy tomorrow. One after another, spontaneous orators spoke standing on car rooves and the demonstrators savored the taste of being masters of the street, in contrast to the aggravations and impotence that they are daily subjected to.

At the Plaza Girardot, a new series of union speeches greeted them, with the aim of putting a stop to ‘all that’. But part of the demonstration, once it arrived at the Plaza, carried on to the Labor Inspectorate building. It was, of course, shut. So they returned to the square. There, thousands of workers, already tired, were sitting in the street on the pavement. They don’t have any clear idea of what to do, but no-one seems to feel like going home to the intolerable, monotonous round of daily life. The leaders had already left, and the union militants were rolling up their banners. Apparently, this is the end.

But it goes on …

Suddenly, at midday, a small demonstration of textile workers appeared. Things got lively again, and a wild march began all through the town, and this time without the union leadership.

First of all, it decided to march together onto the Municipality, where, after filling the staircases on all four floors, the workers demanded a confrontation with the Municipal councilors. These latter didn’t seem to appreciate the insistence of an elderly worker knocking on the door with his stick. Then someone put forward the idea of marching on the premises of the Chamber of Commerce and Industry, where, strangely, nothing was to be found apart from a few cases of mineral water, which were swiftly used to calm the collective thirst. From there, the workers decided to go to the transport terminus. On the way they closed down a construction site and looked up the foreman in order to give him a bit of ‘advice’. With an elevated social and democratic sentiment, they divided up the contents of a poultry shop which had had the unfortunate idea of staying open.

It was after 2 O'clock in the afternoon, and the demonstration had travelled some ten kilometers. Hunger, heat and fatigue had considerably reduced the number of demonstrators. It was time to put an end to the collective intoxication and bring them back to sad reality. Given that the union leadership had failed, this task fell to other organisms. With truncheon blows and other ‘persuasive’ methods5, the ‘forces of order’ showed for the nth time that the streets don’t yet belong to the people, out to the police. At 3 O'clock in the afternoon, order reigned in Maracay.

The day had been extremely rich in lessons. Instinctively, the working class had identified several nerve centers of power; parliament, the Municipal Council, the Ministry of Labor, the unions and the passenger terminus, this latter as a springboard for extending the struggle outside Maracay. It was like a kind of reconnaissance mission for future struggles. Apparently, there were demonstrations during the night in some districts. It was a proletarian holiday.

CTV: Oil on troubled waters

If any worker might have entertained some illusions about this being a first step in a series of triumphant struggles, apparently thanks to the support of the union apparatus, the next day’s papers took care to remind them of their condition as an exploited and manipulated class. In fact, the CTV, as if by magic, transformed the national strike into a general mobilization ... for 4 O'clock in the afternoon of 25 October. Clearly, the CTV didn’t want to be overtaken again by the spontaneous initiative of the masses, and this time on a national scale. Let the workers work all day first, and then go and demonstrate, if they still feel like it! The night would calm down any hot-heads. For the unions, it was now a matter of trying to arrange an impressive demonstration, but without a strike, a formula which would allow them to maintain social control without losing an appearance of militancy. Moreover, some industries in Aragua, profiting from the strike of 17 October’s juridical illegality, carried out massive lay-offs (especially in La Victoria, an industrial town in Aragua, where some 500 workers were made redundant). In this way, they put into practice already planned projects of ‘reduction of personnel’, ‘industrial mobility’, and ‘administrative improvement’. The object was to confront as cheaply as possible the particularly critical financial situation of the small and medium-sized businesses. This maneuver created a very tense situation in La Victoria, with marches and protests opening up a perspective for new struggles in the weeks to come, but this time without the fake support of the CTV. Either the workers of La Victoria will learn to struggle for themselves, or they will be forced to accept the conditions of the dictatorship of capital.

In spite of everything, anger explodes

Despite the characteristics we have described above, the day of ‘national mobilization’ on 25 October gave rise to new demonstrations of the workers’ combativity. In the state of Carabobo, and in Guyana6, there were region-wide strikes with massive and enthusiastic marches. In the capital, Caracas, where union prestige demanded that the demonstration should be well attended, the CTV even took it on itself to bring in coach-loads of workers, who for their part took advantage of their first opportunity in years to express their class hatred. Aware, after the events of the 17th, of the danger of a working class outburst, the government could not allow the demonstration to invade the centre of the capital, as had happened at Maracay. Furthermore, the ‘forces of order’ had themselves decided to confront the workers practically from the outset. This wasn’t an ‘excess’ or a ‘mistake’; the police were just valiantly carrying out their class function. The confrontation took place. Instead of running in panic as usual, the demonstrators put up a stubborn resistance for several hours; they destroyed symbols of bourgeois luxury in the neighborhood, and a climate of violence persisted for several days in the working class districts, especially in “23 de Janero” (a working class district with a very concentrated and combative working class), leaving a balance-sheet of several dead.

Meanwhile, in Maracay, the mass of workers who had already tasted the events of the 17th were not won over to participation in what seemed to everybody to be a watered-down repeat performance. Very few workers bothered to turn up to the meeting. By contrast, the false rumor that a student had been assassinated in Valencia7 (in fact there really had been a death in Valencia: a worker) brought some 2,000 students into the streets. It’s typical of students to be shocked by the murder of one student by the police, and to remain blind to the less spectacular daily destruction of the working class in the factories: 250 fatal accidents and more than a million industrial injuries and diseases a year reveal capitalism’s violence to the full.

It was a student demonstration; the working class character of the 17th had disappeared, the whole affair was drowned in a sea of university, youth and other slogans. Despite this, it was worth noting the absence of the traditional student organizations, and the participation of many ‘independent’ students, who could in the future converge with the emerging workers’ movement. Only a group of teachers -- they were on strike -- maintained a certain class character.

The working class had shown its readiness to express its extreme discontent as soon as the opportunity arose, but it was not, and is not yet, prepared to try to create this possibility autonomously through its own initiative.

From the street to Parliament

Without losing any time, the CTV at once concluded that such an opportunity should at all costs be prevented from arising. In fact, for the moment a relative calm is being imposed -- a situation that could well be overturned when the year’s end bonuses come up, given the financial difficulties of some companies. There is less and less talk of mobilizations, and more of parliamentary negotiations, which are supposed to put through the famous law proposed by the CTV; but this time, there’s no question of applying pressure at street level. On 29 October, the CTV’s consultative council concretized the results of negotiations between social democrats and Christian democrats, and decided that from now on the centre should be informed beforehand whenever a strike movement is decided by the local or craft federations. This was to keep control of any dangerous situation. And once this point was granted, all strikes in the ministries were declared illegal. If the centre behaves like this towards its own federations, you can imagine its attitude when confronted with a workers’ movement acting independently of the unions.

All this throws a clear light on the alternative which supposedly characterizes the unions: of being complaints bureaus or instruments of struggle. In reality, the unions are complaints bureaus in periods of social calm and organs of sabotage of the workers’ struggle as soon as it raises its head.

The old mole shows its nose and the leaders contemplate the heavens

The present situation is one of resurgence of the proletariat on the national scene. This is similar to what happened at the beginning of the sixties and during 1969-72. This resurgence is the product of the end of the oil boom, and of the national bourgeoisie’s delusions of grandeur. Today the bill has to be paid, which in plain language means rationalization of production, bringing bankruptcy in its wake for small and medium-sized companies (the maintenance of whose profits is one of the main preoccupations of our ‘socialists’ -- ah how beautiful capitalism was before there were any monopolies!), and intensified exploitation of the working class.

The liberation of prices is only one weapon of the policy of restructuring the country’s productive apparatus -- a policy which must be carried out along the only lines left to the capitalists: crisis and recession. Contrary to the assertions of the university professors, this policy is not mistaken -- it is inevitable within the framework of the capitalist system. To struggle against this policy without attacking the very foundations of the capitalist system (like those who demand the resignation of the economics cabinet for being supposedly ‘misinformed’ or ‘too ignorant’) is to show a socio-political shortsightedness which comes down to rejecting revolutionary struggle.

What must be put forward in the face of the problems that the development of capitalism imposes on the masses, is the imperative need to go beyond, relations of production determined by money and the market, to the takeover of production and distribution by the freely associated producers.

The bourgeoisie tries to divert the masses’ attention by orienting it towards a wages law, which is reduced to its bare bones thanks to the unions’ own fear of mobilizing the masses. In fact, this law hardly aims to compensate for inflation at the rate measured and recognized by the Venezuelan Central Bank since prices were liberated. Those who claim to be more ‘radical’ do so by demanding a higher percentage or even the nec plus ultra of a sliding scale of wages (which at best comes down to definitively tying the workers’ income to the oscillations of the bourgeois economy). While we’re on the subject, it’s interesting to note that the Brazilian workers have just opposed a similar law, because they say it would diminish their ability to struggle at factory level to win rises much higher than inflation, as did indeed happen at the beginning of the year.

The problem isn’t the percentage of the wage rises. What’s needed is to push forward all those struggles which tend to show up the autonomy of workers’ interests against those of bourgeois society, those struggles which tend to generalize, unifying and extending themselves beyond narrow craft limitations to all sectors in struggle, all those which tend to attack the very existence of wage labor. It’s not so much the particular reasons behind each struggle which matter but the organizational experience gained during them. It’s possible, moreover, to distinguish a watershed in the proletariat’s activity when we consider that since 1976, the number of strikes has not stopped growing, while the same has not been true for the deposition of the ‘claim casebooks’ demanded by law. This seems to indicate that the working class feels itself less and less concerned with bourgeois legality, that its action tends more and more to be a direct function of its interests.

Confronted with the liberation of prices, the workers will have to impose a liberation of wages; just as they will have to tear into shreds the schedules laid down in wage agreements. They will have to prepare themselves for a daily and permanent struggle in their workplaces and in the street.

The workers in Venezuela are not alone

What’s happening in Venezuela is not unique in the world; on the contrary, we are simply taking part in a phenomenon of universal dimensions. Nowhere has capitalism succeeded, and nowhere will it succeed, in satisfying humanity’s needs in a stable way. Unemployment in Europe and China, inflation in the USA and in Poland, nuclear insecurity and insecurity in the food supply, with the social struggles they engender, are the witnesses.

The battle-cry of the Ist International is still on the order of the day:

“The emancipation of the working class will be the work of the workers themselves.”

Venezuela,

November, 1979

1 PAD: Partido Accion Democratica (social democrat). Went into opposition at the last presidential elections which brought the Social Christians in power.

2 CTV: Confederacion dos Trabajadores Venezuelons (Venezuelan Workers’ Confederation) dominated by the PAD.

3 Aragua is one of the states of Venezuela (textiles being the most important industry). Venezuela’s national anthem says “Follow the example of Caracas”.

4 Important representative of Venezuelan bosses.

5 In Venezuela, the police have the habit of beating up demonstrators with the flats of machete blades.

6 Two regions where industry is concentrated (engineering and steelworks).

7 Capital of the state of Carabobo.

Geographical:

- Venezuela [4]

Behind the Iran-US crisis, the ideological campaigns

- 2371 reads

Ten months after a ‘revolution’ which accomplished the great feat of setting up an even more anachronistic regime than the one before it, the situation in Iran has forcefully returned to the centre of world affairs, giving rise to a tidal-wave of curses against the ‘barbarism’ of Iranians and Muslims, and of alarmist predictions about the threat of war or economic catastrophe. In the midst of all this noise and furor, so complacently spread around by the mass media, it’s necessary for revolutionaries to look at the situation clearly and in particular to answer the following questions:

1. What does the seizure of hostages in the American embassy tell us about the internal situation in Iran?

2. What impact does this operation and this situation have on the world situation, in particular:

*** -- what are the big powers playing at?

*** -- is there really a danger of an armed conflict?

3. What lessons can be drawn from it about the general perspectives facing society in the next decade?

1. The taking of diplomatic personnel as hostages by a legal government is a sort of ‘first’ even in the agitated world of contemporary capitalism. The taking of hostages in itself is a common occurrence in the convulsions of a decadent capitalism: in all inter-imperialist confrontations entire populations can fall victim to this without causing any anxiety to the international community of imperialist brigands. The particularity and ‘scandalous’ character of what’s been going on in Teheran resides in the fact that this has upset the elementary rules of etiquette which these brigands have established.

Just as it’s the golden rule in the world of gangsters to keep quiet in front of the police, so respect for diplomats is the golden rule of the leaders of capitalism. The fact that the leaders of Iran have adopted or sanctioned the kind of behavior that is generally reserved to ‘terrorists’ speaks volumes about the level of political decomposition in this country.

In fact, since the departure of the Shah, the ruling class of Iran has shown itself incapable of ensuring the most elementary level of political stability. The near-unanimity which was achieved by the forces of opposition against the bloody and corrupt dictatorship to the Shah has rapidly disintegrated, owing to:

*** -- the heterogeneous nature of the social forces fighting against the old regime;

*** -- the completely anachronistic character of the new regime, which bases itself on medieval ideological themes;

*** -- the inability of the regime to give any satisfaction to the economic demands of the poorest strata, in particular the working class;

*** -- the significant weakening of the armed forces, which were partly decapitated after the

fall of the Shah, and in which demoralization and desertion are becoming rife.

In just a few months, opposition to the government has developed to the point of totally undermining the cohesion and the economic base of the social edifice. This includes:

*** -- the opposition from the ‘liberal’ and modern sectors of the bourgeoisie;

*** -- the secession of the Kurdish provinces;

*** -- the resurgence of proletarian struggles which are more and more threatening what is almost the only source of the country’s wealth: the production and refining of oil.

Faced with the general decomposition of society, the leaders of the ‘Islamic Republic’ have gone back to the theme which managed to achieve an ephemeral unity ten months ago: hatred for the Shah and for the power which supported him until his overthrow and is now harboring him. Whether the occupation of the American embassy was ‘spontaneous’ or was wanted by the ‘hardline’ Iranian leaders (Khomeini, Bani-Sadr) doesn’t alter the fact that the bugbear of the Shah has -- like the fascist bugbear in other circumstances -- been used to re-establish a momentary ‘national unity’, expressed by:

*** -- the cease-fire of the Kurdish nationalists;

*** -- the banning of strikes by the ‘Council of the Revolution’.

But in the long run the remedy chosen by Khomeini and Co will make things worse than ever and show that the present ruling team is in an impasse: by choosing a political and economic confrontation with the USA, it can only end up by aggravating the internal situation, especially on the economic level.

2. The convulsions which are now shaking Iran are a new illustration of:

a. the gravity of the present crisis of world capitalism, expressing itself in increasingly profound and frequent political crises in the advanced countries, and, in the backward countries, in the almost total decomposition of the social body;

b. the impossibility of any real national independence for the under-developed countries: either they must align themselves tamely behind one bloc or the other, or they will be plunged into such instability and economic chaos that they will sooner or later be forced to tow the line in the same way: it’s impossible to see Iran under the Imam Khomeini succeeding where De Gaulle’s France and Mao’s China failed.

3. Contrary to all the alarmist rumors, the present convulsions in Iran are not giving rise to the immediate threat of a major military confrontation in the region. The essential reason for this is that, despite the whole anti-American campaign being conducted by Khomeini, there is no possibility today of Iran going over to the Russian bloc. As has been shown many times in the past, notably in the Cyprus affair of 1974, the difficulties and instability that may arise in a country within the US bloc, in so far as they weaken the cohesion of the bloc, may be a generally favorable factor for Russia, but this doesn’t necessarily mean that the Russians are in a position to really take advantage of the situation. At the present moment, the USSR, which is already having great difficulties with the Muslim guerillas in Afghanistan and which has to bear in mind the possible threat of nationalist agitation among its own Muslim populations, is not in a position to get its hands on a country which is being swept by the ‘Islamic wave’. This is all the more evident when we consider that there is no political force in Iran capable of leading the country into the Russian bloc (the CP is weak and the army is well controlled by the US bloc).

4. For some months the situation in Iran has been getting out of the US control. The US made the mistake of supporting for too long a regime that was completely discredited, even in the eyes of most of the ruling class; this led to the failure of its last-minute attempts to achieve a smooth transition to a more ‘democratic’ regime (in the person of Bakhtiar) capable of dampening down popular discontent. Once the army began to fall apart in February 1979, this transition took place in a heated atmosphere, in favor of a political force which was momentarily the most ‘popular’ but which in the long run is the least capable of managing Iranian capital in a lucid and effective manner. At the present time we are seeing a new stage in the US bloc’s efforts to regain control of the Iranian situation: after the failure of the ‘progressive’ solution represented by Bazargan, it’s now letting the local situation go to pieces. Like the declaration of war on the US and the European powers by the Venezuelan dictator Gomez in the 1930s, the Iranian decision to declare not just a ‘holy war’ but an economic war on the US is truly suicidal: the interruption of trade between Iran and the US may cause minor perturbations for the latter, but it will condemn Iran to economic strangulation. The US policy therefore boils down to letting the present regime stay in the impasse which its now reached, allowing it to isolate itself from the various sectors of society, so that it can pick the fruit when it’s ripe, replacing the Khomeini clique with another governmental team, which would have to have the following characteristics:

*** -- being more conciliatory towards the US;

*** -- being more capable of controlling the situation;

*** -- having the support of the army (if it’s not the army itself), seeing that the army is crucial to the political life of all third world countries.

Without pushing the analogy too far, it’s probable that Iran will go through a similar process as Portugal did. Here political instability and the preponderance of a party that was hostile to the USA (the PCP) -- the result of the late and brutal transition from a completely discredited dictatorship -- were eliminated following pressure from the US bloc on the diplomatic and economic level.

5. There is every reason to suppose that this trial of strength between Iran and the USA, far from representing a weakening of the American bloc, will serve to strengthen it. Apart from the fact that it will sooner or later allow the US to get a firmer grip on the Middle East situation, it will constrain the western powers (Europe, Japan) to strengthen their allegiance to the leading country of the bloc. This allegiance has been somewhat disturbed recently by the fact that these powers were (apart from the backward non-oil producing countries) the main victims of the oil price-rises underhandedly encouraged by the USA (cf. International Review, no.19). The present crisis highlights the fact that these powers are much more dependent on Iranian oil than America. This compels them to close ranks behind their leader and collaborate in its efforts to stabilize this part of the world. The relatively moderate way that these powers (notably France) have condemned Khomeini shouldn’t delude us: if they didn’t tie their hands straight away, it’s because this will leave them better placed to make a contribution -- especially on the diplomatic level -- to the US bloc regaining control of the situation. As we’ve already seen in Zaire, for example, one of the strengths of this bloc is its ability to have its less ‘compromised’ members intervene in situations where the dominant power itself is unable to act directly.

6. While one of America’s objectives in the present crisis is to strengthen the international cohesion of its bloc; another, even more important objective is to whip up a war psychosis. Never has the misfortune of fifty American citizens caused so much concern to the mass media, the politicians and the churches. A torrent of war hysteria like this hasn’t been seen for a long time; it’s even reached the point where the government, which orchestrated the campaign in the first place, is now playing the role of moderator. Faced with a population that has traditionally not been favorable to the idea of foreign intervention, a population which was only mobilized for world war by the attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941, and which has been markedly cool towards adventures of this kind since the Vietnam war, the ‘barbarous’ acts of the ‘Islamic Republic’ have been an excellent theme for the war campaigns of the American bourgeoisie. Khomeini has found the Shah to be an excellent bugbear to use for re-forging the unity of the nation. Carter -- whether, as it would seem, he deliberately provoked the present crisis by letting the Shah into the States, or whether he’s merely using the situation -- has found Khomeini to be an equally useful bugbear in his efforts to reinforce national unity at home and get the American population used to the idea of foreign intervention, even if this doesn’t happen in Iran. The difference between these two maneuvers is the fact that the first is an act of desperation and is going to quickly rebound on its promoters, whereas the second is part of a much more lucid plan by American capital.

The USA isn’t the only country to use the present crisis to mobilize public opinion behind preparations for imperialist war. In Western Europe, with themes adapted to the local situation, the whole barrage about the ‘Arab’ or ‘Islamic’ peril (similar to the old ‘Yellow Peril’) being the source of the crisis, is part of the same kind of preparations, the same kind of war psychosis.

As for the USSR, even if, for the reasons that we’ve seen, it isn’t trying to exploit the situation from the outside, it is trying to respond to the western campaign about ‘human rights’ by denouncing the ‘imperialist threats’ of the USA and proclaiming its solidarity with the anti-American sentiments of the Iranian masses.

7. Even if it’s reached a caricatural level in Iran, as in all the under-developed countries, the decomposition of Iranian society is by no means a local phenomenon. On the contrary, the virulence of the ideological campaigns being waged by the main powers indicates that the bourgeoisie everywhere is up against the wall; that it’s more and more taking refuge in a headlong flight towards a new imperialist war; and that it feels the masses’ lack of enthusiasm for its warlike objectives as a major obstacle to its plans.

For revolutionaries, the task is once again:

*** -- to denounce all these ideological campaigns, wherever they come from, whatever mottoes they use (human rights, anti-imperialism, the Arab menace, etc.), and whoever their promoters are -- right or left, east or west;

*** -- to insist that humanity’s only alternative to a new holocaust, the only way to avoid its own destruction, is the intensification of the proletarian offensive and the overthrow of capitalism.

28 November, 1979, ICC.

Historic events:

Geographical:

- United States [6]

- Iran [7]

General and theoretical questions:

- Imperialism [8]

ICC Statement on Afghanistan

- 2500 reads

Afghanistan: There’s only one way to fight the threat of world war: By strengthening the proletarian struggle

With the events in Afghanistan and all their repercussions, capitalism has taken one more step towards world war. It would be criminal to hide this fact.

Up till now, through its struggle, through its refusal to submit passively to the diktats of austerity the world proletariat has prevented the bourgeoisie from imposing its apocalyptic solution to the crisis of its economy. It must now take its struggle onto a higher level. In order to do that, the workers must not abandon their struggles of economic resistance, but on the contrary unify them, generalize them, and above all take up their real meaning in a resolute and consistent manner: in other words, see them as part of the struggle to do away with the barbarism of war by destroying the capitalist economic laws which give rise to it.

Once again, the threat of war is shaking the world. Only a year ago, under the pretext of ‘punishing’ Vietnam for its actions in Cambodia, China went onto the offensive with over 300,000 soldiers in a war that left tens of thousands dead in a few days. Today, another so-called ‘socialist’ country, under the guise of ‘helping a regime threatened by the hands of imperialism’, has sent 100,000 soldiers of its ‘Red Army’ to put another country under military occupation. But whereas last year the specter of world war was quickly extinguished after the initial alert, today there’s nothing fleeting about this threat. On the contrary, even before the USSR’s intervention in Afghanistan, the danger of war was being frantically stirred up in the press, on television, and in the speeches of the politicians.

What is the meaning of the USSR’s invasion of Afghanistan?

What underlies the present campaigns about the threat of war?

How can a third imperialist holocaust be prevented?

The lies of the bourgeoisie and the threats of war

Like the time that it invaded Czechoslovakia in 1968, the USSR claims that it has sent in its divisions ‘at the request of a friendly people threatened by imperialism’. This lie is as old as war itself. Capitalism has always launched its imperialist wars to ‘defend itself from foreign threats’ or to ‘protect’ this or that people. Hitler invaded Czechoslovakia in 1938 to ‘protect’ the German-speaking population of the Sudetenland. In the mid-sixties, the USA sent in half a million soldiers to ‘defend’ South Vietnam against ‘Communist aggression’. Imperialist propaganda has a long list of lies. Today the American bloc is playing the game of denouncing the Russian intervention and its hypocritical justifications, because it will use every chance it can get to step up its own propaganda in favor of its own imperialist designs and war preparations. Under the pretext of facing up to the ‘Russian danger’ -- which is the subject of a deafening barrage by the press, radio and television -- the American bourgeoisie and its allies are pushing ahead not only with their ideological campaigns, but also with an enormous deployment of military forces (the Pershing II missiles in Europe, naval forces in the Indian Ocean, the supplying of arms to China and Pakistan).

This ideological campaign isn’t new. It’s already several years since Carter and his friends began preparing public opinion for the idea of a war against the USSR under the pretext of ‘defending human rights’. More recently the oil price rises, and above all the seizure of the hostages in Tehran, have been used as an excuse to step up the whole war-campaign: in order to ‘defend our security’ and ‘protect our interests’, we must be prepared for military intervention abroad. Today, with the invasion of Afghanistan, the campaign has reached new heights. Using all the means at its disposal, the bourgeoisie is trying to get us used to the idea that ‘war is becoming inevitable’, that its ‘someone else’s fault’, that whether we like it or not there’s no alternative and we’d better get ready for it.

Is war inevitable?

It is from capitalism’s point of view. Two worldwide butcheries have shown that generalized war is the only response that this system can have to the aggravation of its economic crisis.

War doesn’t happen simply because there are particularly warlike regimes -- Germany yesterday or Russia today. All countries are preparing for war, all governments are continuously increasing their military budgets, all governments and all parties -- including the so-called workers’ parties -- call for ‘defending the fatherland’, for the national defense which has cost humanity more than 100 million lives since 1914. All of them bear the same responsibility for the holocausts of the past and for those future holocausts which capitalism is preparing. When gangsters are settling scores amongst themselves, what’s the point in asking who fired the first shot? Before a war, the imperialist gangsters who’ve got the most loot generally have the luxury of presenting themselves as the ‘victims of aggression’. After the war, it’s always discovered, as if by chance, that the ‘aggressors’ were the losing side. In imperialist wars, all countries are ‘aggressors’; the only victims of aggression are the exploited masses who are sent to the slaughter to defend their respective bourgeoisies.

Today the bourgeoisie in all countries is accentuating its preparations for war because the crisis of its economy has got it by the throat. For years, it has tried to overcome the crisis by all sorts of policies, all of which had one thing in common: austerity for the workers. But despite this ever-increasing austerity, each one of the remedies tried out by the bourgeoisie has only made the disease worse. Each time it has tried to reduce inflation it’s only succeeded in reducing production; each time it’s tried to raise production it’s only succeeded in raising inflation. As long as it thought it could get out of this situation, it kept telling the workers that they must ‘make sacrifices today so that things will get better tomorrow’. But reality is more and more giving the lie to such optimism. More and more, the impasse facing its economic system has forced the bourgeoisie to make a ‘retreat forward’ -- and that can only mean towards war. In the last few years there has been a proliferation and aggravation of local wars behind which the major imperialist powers have confronted each other: Africa, Cambodia, Vietnam-China, and now Afghanistan. The USSR’s invasion of this country in no way means that ‘socialism is essentially warmongering’. What it does show is that this country -- like China and all the others that call themselves ‘socialist’ -- is capitalist and imperialist like all the rest, that it is subject to the same world crisis which is hitting the entire capitalist system, that everywhere capital is incapable of overcoming the crisis and is everywhere being pushed towards war.

Thus, all over the world, the bourgeoisie is increasingly becoming aware that the only perspective it has is a new generalized war.

In fact, from the point of view both of the level of the crisis and the level of armaments, the conditions for a new world butchery are much riper than they were in 1914 or 1939. What, up to now, has stayed the criminal hands of the bourgeoisie is its incapacity to mobilize the population, and the working class in particular, behind its imperialist objectives. The workers’ struggles which have developed since 1968 are the sign that, up to now, the bourgeoisie has not had a free hand to impose its own response to the insoluble crisis of its economy: world war.

And it’s precisely to change this state of affairs that the bourgeoisie is now intensifying its ideological barrage about the danger of war.

The bourgeoisie is less and less pretending that ‘things will be better tomorrow’. On the contrary, it’s now demanding sacrifices from the workers while letting them know that it’s going to demand more and more sacrifices, including the supreme sacrifice -- their lives, in a generalized war. It is now feeding us the following line: it’s true that there’s a danger of war, but war is an inevitability which doesn’t depend on us and which we can’t avoid. We must therefore strengthen national unity, accept sacrifices, put up with all the austerity implied by all the armaments programs.

What is the way out for the working class?

It’s true that war is an inevitability for the bourgeoisie! From its point of view, in its logic, its the only perspective it can offer society. And its whole campaign today has no other aim than to get the working class to accept this point of view, this logic. While it expresses a real threat hanging over humanity, the whole deafening barrage about war is aimed at instilling a mood of resignation in the workers, an acceptance of a new holocaust that will be even more terrible than the two previous ones.

And if the workers accept the logic of the bourgeoisie, then yes, world war is inevitable!