The sources, contradictions and limitations of the growth in Eastern Asia

- 5433 reads

Asian Growth: an expression of the crisis and decadence of capitalism

Up to now capitalism has shown a conspicuous inability to develop the countries where two-thirds of humanity live. Now, with the incredible economic growth in India and China - and throughout East Asia generally - we hear it shouted from the roof tops that from henceforth it will be able to develop more than half the world and that it would be able to go even further if only all the constraints imposed on it were to be eliminated. If wages and working conditions were to be levelled down to those obtaining in China, it is claimed, then growth in the West would also rise to 10% a year.

This raises theoretical and ideological questions of great importance: does the development in East Asia represent a renewal of capitalism or is it no more than a stray occurrence in its on-going crisis? To answer this question we will consider the phenomenon throughout the whole of the sub-continent, though we will examine China more closely as it is the most publicised and the most representative example.

Some questions for revolutionary theory posed by development in the Asian sub-continent

1) In 25 years of economic crisis and ‘globalisation'[1] (1980-2005), Europe has increased its GDP (Gross Domestic Product) by a factor of just 1.7, the United States by 2.2 and the world by 2.5. India, on the other hand, has managed to increase it four-fold, developing Asia six-fold and China ten-fold. This means that the latter has developed 4 times more rapidly than the international average and it has done so during a period of crisis. Therefore, over the last two decades, growth in the Asian sub-continent has cushioned the continual fall in the growth rate of international GDP per head of population. This has been uninterrupted since the end of the 1960s: 3.7% (1960-69); 2.1% (1970-79); 1.3% (1980-89); 1.1% (1990-1999) and 0.9% for 2000-2004)[2]. The first question to ask therefore is: will this region of the world escape the crisis that is undermining the rest of the world economy?

2) It took the United States fifty years to double its per capita income between 1865 and the First World War (1914): China has managed to do so in half the time and in the midst of the decadent period and the capitalist crisis. Although 84% of the Middle Empire was rural in 1952, the number of workers in China's industrial sector is now 170 million, that is, 40% greater than in all of the countries of the OECD (123 million). This country is becoming the workshop of the world and employment in the tertiary sector is increasing at a very rapid rate. The transformation of the employment structure is one of the fastest ever to have taken place in the history of capitalism.[3] China has already become the fourth largest economy in the world if its GDP is calculated using the exchange rate of the dollar and it is in second place if the calculation is made in terms of parity in buying power[4]. These facts must obviously lead us to ask if this country is experiencing a genuine primitive accumulation and an industrial revolution, such as occurred in the developing countries during the XVIII and XIX centuries. To put it another way: is it possible for new capitalist countries to emerge during the period of capitalist decadence? Moreover, is it possible for a country to catch up with the others, as was the case during the ascendant period? If China's present rate of growth were to continue, in less than two decades, it would become one of the largest world powers. This is what the United States and Germany did in the XIX century, when they managed to catch up with and overtake England and France, in spite of the fact that they had begun to develop later.

3) The development of China's GDP is also the most dramatic in the entire history of capitalism. It has had an average annual increase of between 8 and 10% over the last 25 years of world-wide crisis. China's growth even exceeds the records attained during the period of prosperity following the war, when Japan grew at a rate of 8.2% per annum between 1950 and 73 and South Korea by 7.6% per annum between 1962 and 1990. What's more, at present this rhythm is much faster and more stable than that of its neighbours who were industrialised earlier (South Korea, Taiwan and Hong Kong). So is China experiencing its own equivalent of the post-1945 economic boom?

4) Moreover, China is not content to simply produce and export basic goods or to re-export goods produced in its workshops for low wages. It is tending more and more to produce and export goods that have a high level of added value, such as electronics and transport equipment. Does this mean that we are about to see a technological development in China similar to that in the NIC (Newly Industrialised Countries: South Korea, Taiwan, Hong Kong and Singapore)? Will China, like them, be able to reduce its dependence on exports and start to develop its internal market? In other words, are India and China no more than shooting stars that will eventually burn out or will they become new major players on the world stage?

5) The rapid formation of an enormous bastion of the international working class in the Asian sub-continent, although young and inexperienced, raises numerous questions about the development of the class struggle in this part of the world and about its influence on the balance of forces between classes at an international level. The increase in the number of class conflicts and the emergence of political minorities are clear signs of this[5]. On the other hand, the low wages and very precarious working conditions in East Asia are used by the bourgeoisie in the developed countries to blackmail (by threatening to re-locate) and to depress wages and working conditions.

These questions can only be answered and the real sources, contradictions and limitations of growth in Asia be assessed, if they are considered within the general context of the evolution of capitalism at an historic and international level. This means that the present development in East Asia must be placed within the framework of the decadent period of capitalism that began in 1914 (Part 1) and in terms of the dynamic of the crisis that re-emerged internationally at the end of the 1960s (Part 2). This alone will enable us to draw out the essential elements relating to Asian growth (Part 3) and these are the analytical axes that will be developed in this article[6].

[1] Read our article "Behind the ‘globalisation' of the economy: the aggravation of the capitalist crisis" in n°86 of this Review.

[2] Sources: World Bank: World Development Indicators 2003 (version on line) and International Economic Perspectives 2004.

[3] Table 1: Different branches' share of produced value and employment (%)

| Primary (agriculture) |

Secondary (industry) |

Tertiary (services) |

||||

| Value | Employment |

Value |

Employment |

Value |

Employment |

|

| 1952 | 51 | 84 |

21 |

7 |

29 |

9 |

| 1978 | 28 | 71 |

48 |

17 |

24 |

12 |

| 2001 | 15 | 50 |

51 |

22 |

34 |

28 |

| Source : China Statistical Yearbook, 2002. |

[4] This calculation method is more reliable in as far as it is based on a comparison of the price of a basketful of goods and standard services in the various countries, rather than just on the value of the respective currencies in terms of the exchange of goods on the world market.

[5] We refer the reader to our Report on the Conference in Korea, at which there met together a number of groups and elements whose basis is proletarian internationalism and the Communist Left (International Review n°129) and to the internet site of a new internationalist political group which has appeared in the Philippines and which sees its political affiliation as being with the groups of the Communist Left (see our internet site).

[6] Our 17th International Congress (see International Review n°130) devoted a significant part of its work to the economic crisis of capitalism; dealing specifically with the present growth in certain ‘emerging' countries such as India and China, as this seems to contradict the analysis made by our organisation, and by Marxists in general, about the definitive bankruptcy of the capitalist mode of production. It made the decision to publish articles deepening this question in its press, especially the International Review. The present text is a concretisation of this orientation and we think that it makes a valuable contribution to understanding growth in China within the framework of the decadence of capitalism. However the discussions that are taking place at present within our organisation, about the mechanisms that enabled capitalism to experience a spectacular level of growth after the Second World War, are taking up the question of how to understand the present dynamism in the economies of certain ‘emerging' countries, China in particular. This article raises a point of disagreement in that it defends the idea that the wage mass could constitute a soluble outlet for capitalist production, as long as it is not ‘compressed' to a minimum. This is expressed in the following formulation concerning the present ‘globalisation' which "is deformed in that it lowers the wage mass and restrains the basis of accumulation internationally". This is not the opinion presently held by the majority in the central organ of the ICC. The majority holds, for reasons that we cannot go into here, that if capitalism is led to ‘benefit' the working class with a buying power greater than that which is strictly necessary for it to reproduce its labour power, the increased consumption of the workers does not in any way benefit accumulation in a lasting way.

Geographical:

General and theoretical questions:

- Economics [3]

Part 1: a trajectory characteristic of capitalist decadence

- 4397 reads

China is typical of those countries that were unable to take part in the process of industrial revolution that took place in the ascendant period of capitalism; it is marked by the colonial yoke and its failure to carry out the bourgeois revolution, although it made several abortive attempts to do so. As long ago as 1820 China was the first world power economically with a GDP that was as much as a third of the wealth produced world-wide but by 1950 China's GDP was only 4.5%. That is, it was reduced seven fold relative to the rest of the world.

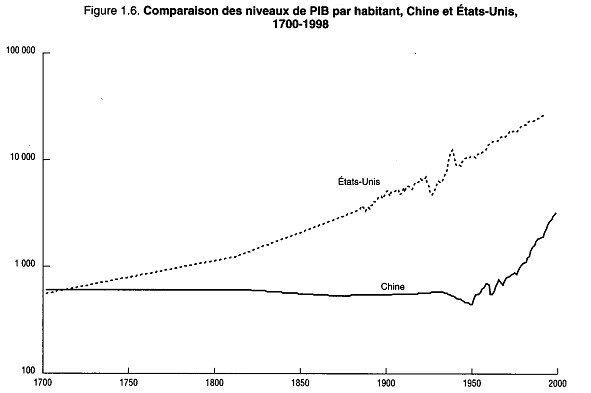

The above graph shows a reduction of 8% in GDP per head of population in China throughout the ascendant period of capitalism: it went from $600 in 1820 to $552 in 1913. This betrays the absence of a real bourgeois revolution and recurring conflicts between the various warlords within the weak dominant class. It is also bears witness to the heavy colonial yoke that the country endured after it was defeated in the Opium War of 1840, a defeat that was the beginning of a series of humiliating treaties that carved up China in the interests of the colonial powers. An already weakened China was ill-equipped to confront the conditions imposed by capitalism's entry into decadence. The relative saturation of the markets and their domination by the big powers, which are characteristic of the whole period of capitalist decadence, condemned China to absolute underdevelopment for the majority of this period and its GDP per head diminished even more rapidly (-20%) between 1913 ($552) and 1950($439).

All these elements fully confirm the analysis developed by the Communist Left, which holds that in decadence it is no longer possible for new states and powers to emerge, given that the world market is saturated[1]. Only in the 1960s did Chinese per capita GDP return to its 1820 level ($600). It increased perceptibly thereafter but it is only during the last thirty years that its growth has leapt to figures never seen before in the whole history of capitalism[2]. It is this recent period in China's history which is exceptional and which must be explained, as it apparently contradicts certain givens about the evolution of capitalism.

However, before examining the real nature of this incredible growth in East Asia, we must mention briefly two other characteristics of decadent capitalism that the analysis of the Communist Left has brought out. They are factors that have had a big impact on the Asian continent: the general tendency towards state capitalism and the integration of every country into an imperialist bloc that promises it protection. Here too the recent evolution of China seems apparently to contradict these characterisations. On the one hand, China plays the lone wolf on the international scene. On the other hand, the way in which it continually carries out reforms and eases controls makes it look like capitalism in 19th century Manchester, as described by Marx in Capital or by Engels in The Condition of the Working Class in England. We can say very briefly that this is by no means the case. On the latter point, all these reforms are carried out on the initiative of the state and under its strict control. On the first point, it is the implosion of the two (US and Russian) imperialist blocs after 1989 that has enabled every country to play ‘lone wolf' since then. We will examine these two factors before explaining the economic success in East Asia over the last quarter of a century.

The General Infrastructure of State Capitalism in Decadence

As we stated in 1974 in a long analysis of state capitalism:"The tendency towards state control is the expression of the permanent crisis experienced by capitalism since 1914. It is the system's way of adapting in order to survive once the economic locomotive of capitalism has no further capacity historically. Once the contradictions of capitalism have become such that they can only tear the world apart because rivalry and imperialist war are inevitable, state capitalism expresses the tendency towards autarchy, permanent economic war and national concentration in order to protect the national capital. (...) during the decadent period the permanent crisis of the system makes it necessary to make certain changes to the organisational structure of capitalism because of the relative saturation of the markets. (...) As there is no simple economic solution to these difficulties, the blind laws of capitalism cannot be left to work themselves out freely. The bourgeoisie tries to control their consequences by means of state intervention: subsidies, the nationalisation of sectors in deficit, control of raw materials, national planning, monetary budgets, etc." (Révolution Internationale old series n°10, pg 13-14).

This analysis is simply the position developed by the Communist International in 1919:"The nation state was once an energetic impulsion to capitalist development but now it has become too narrow for the expansion of the productive forces", as it states in its Manifesto. This contradiction between the social relations of capitalist production and the brake that they now apply to the development of the productive forces is at the heart of the general tendency towards state capitalism during the decadent period of capitalism. The bitter competition on a world market that is now globally saturated and controlled by the big powers, obliges each nation state to try to control its fate by implementing measures of state intervention at all levels: social, political and economic. In general the development of state capitalism in decadence expresses insoluble contradictions between the needs of the accumulation of capital, which becomes more and more international, and the narrow national framework of bourgeois property relationships. "State control of economic life is a fact, however much liberalism may protest. To return, not only to free competition, but also to the domination of trusts, syndicates and other capitalist formations, is now impossible", affirms the Manifesto of the Communist International mentioned above.

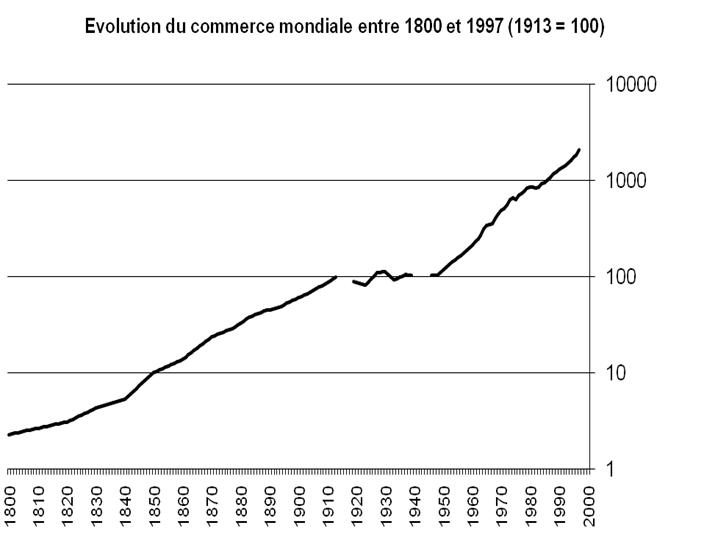

The tendency for the state to take control of the national interest and for there to be a withdrawal into the national framework produced a sharp halt in the expansion and internationalisation of capitalism that took place during the whole of the ascendant period. During this period, the exports of the developed countries as a proportion of world production went on growing to the point that they more than doubled. In fact they went from 5.5% in 1830 to 12.9% on the eve of the First World War (table 2). This illustrates capitalism's relentless conquest of the world in this period.

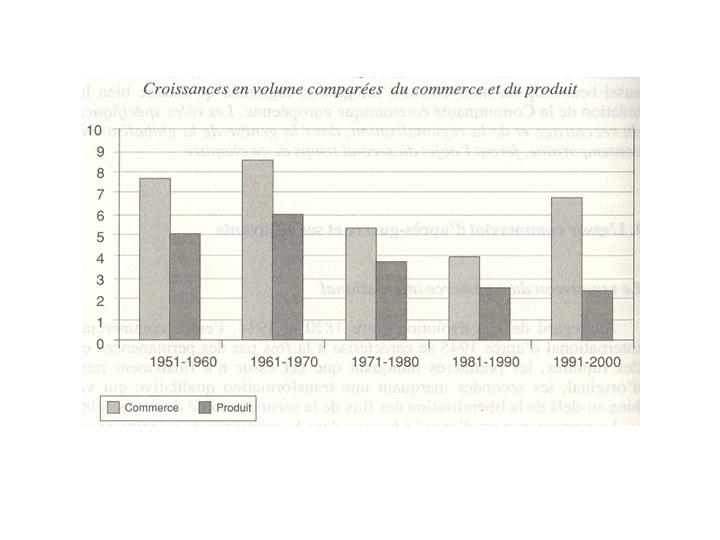

However the entry into capitalism's decadent period was marked by a sharp halt to capitalism's penetration of the world. The stagnation of world trade between 1914 and 1950 (graph 2), the halving of the exports of the developed countries as a proportion of world production (from 12.9% in 1913 to 6.2% in 1938 - table 2) and the fact that the growth in world trade was very often inferior to that of production, showed in their different ways the marked retreat into the framework of the nation state during the decadent period. Even during the auspicious period of the post-war boom, which saw an energetic recovery of world trade up until the 1970s, the percentage exports of the developed countries (10.2%) always remained less than their 1914 level (12.9%) and were even lower than in the 1860s (10.9% - see table 2[3]). It was only thanks to the phenomenon of ‘globalisation' from the 80s onwards that the proportion of exports rose above the level it had attained more than a century earlier.

This distinction between the dynamic operating in the ascendant period of capitalism in contrast to that in its decadent period holds true also in terms of the flow of investments between countries. The proportion of Direct Foreign Investment (DFI) increased to 2% of world GDP in 1914 whereas it only reached a half of this (1%) in 1995 in spite of the fact that it has developed considerably as a result of globalisation. This is also true in terms of DFI in the developed countries. Although globalisation has doubled DFI from 6.6% in 1980 to 11.5% in 1995, this percentage is no greater than the 1914 figure (between 12% and 15%). This economic focus on the national level and the developed countries in the decadent period is also illustrated by the following: "On the eve of the First World War 55 to 65% of DFI was to be found in the Third World and only 25-35% in the developed countries. At the end of the 1960s this relationship was reversed; in 1967 only 31% of the DFI stocks of the developed Western countries went to the Third world and 61% remained in the developed countries in the West. Since then this tendency has been further reinforced. (...) Towards 1980 these proportions became 78% of DFI in the developed countries and 22% in the Third World. (...) This shows the importance to GDP of direct investment within the developed countries of the West, which was round about 8.5% to 9% in the middle of the 1990s, in comparison to 3.5 to 4% around 1913. That is, it more than doubled."[4]

Whereas ascendant capitalism transformed the world in its own image by drawing more and more countries into its orbit, its decadence somehow froze the situation as it had been at its zenith: "The impossibility of any new big capitalist units arising in this period is also expressed by the fact that the six biggest industrial powers today (USA, Japan, Russia, Germany, France, Britain) were already at the top of the tree (even though in a different order) on the eve of the first world war" (International Review n°23, ‘The Proletarian Struggle under Decadent Capitalism', , p.24). All of this illustrates the dramatic retreat into the national framework that characterises the whole phase of capitalist decadence and is carried out by means of energetic state capitalist policies.

|

Table2 : Western developed countries exports in value (% GDP) |

|

|

1830 |

5,5 |

|

1860 |

10,9 |

|

1890 |

11,7 |

|

1913 |

12,9 |

|

1929 |

9,8 |

|

1938 |

6,2 |

|

1950 |

8 |

|

1960 |

8,6 |

|

1970 |

10,2 |

|

1980 |

15,3 |

|

1990 |

14,8 |

|

1996 |

15,9 |

|

Philippe Norel, L'invention du marché, Seuil, 2003 : 431. |

The whole of East Asia was particularly affected by this general withdrawal into the framework of the nation state. Following the Second World War almost half the world population was excluded from the world market and cordoned off by the division of the world into two geo-strategic blocs, a situation that only came to an end in the 80s. Those involved were the Eastern bloc, China, India and several countries of the Third World such as Cuba, Vietnam, Cambodia, Algeria, Egypt, etc. This brutal exclusion of half the world from the market is a clear illustration of the relative saturation of the world market. It meant that, in order to survive the hell of decadence, each national capital was forced to take direct command of its own interests at a national level and integrate itself into the policies adopted by the two big powers, so obtaining their protection. Even so, this policy that they were forced to adopt was a conspicuous failure. In fact, the entire period experienced fairly mediocre growth for India and China, especially the former, which did even less well than Africa:

|

Table 3 : Per capita GDP (Index 100 = 1950) |

||

|

|

1950 |

1973 |

|

Japan |

100 |

594 |

|

Western Europe |

100 |

251 |

|

United States |

100 |

243 |

|

World |

100 |

194 |

|

China |

100 |

191 |

|

Africa |

100 |

160 |

|

India |

100 |

138 |

|

Source : Angus Maddison, L’économie mondiale, annexe C, OCDE, 2001. |

It is true that growth in China was higher than that of the whole of the Third World between 1950 and 1973 but it was still less than half of world growth, and was based on a brutal super-exploitation of the peasants and workers. It was only possible thanks to the strong support of the Eastern bloc up until the 1960s and to China's integration into the American sphere of influence thereafter. Moreover it experienced two serious down-turns during the periods known as "the Great Leap Forward" (1958-61) and the "Cultural Revolution" (1966-70), which murdered millions of Chinese peasants and proletarians through atrocious famine and material suffering. We pointed out this global failure of the policies of autarchic state capitalism more than a quarter of a century ago: "In the 20th century protectionist policies have been a total failure. Far from allowing the less developed economies to have a breathing space, they have led to the asphyxiation of the national economy" (International Review n°23, ‘The Proletarian Struggle under Decadent Capitalism', p.24). This is because state capitalism is not a solution to capitalism's contradictions but is rather a placebo that enables it to postpone their effects.

China switches from one imperialist bloc to the other

On its own China was unable to confront the intense competition on a world market that was globally saturated and controlled by the big powers. In order to best defend its national interests it had to join first the Soviet bloc, where it remained until the beginning of the 1960s, and then to move into America's orbit from the 1970s. This was a necessary condition for the defence of a nationalist plan for ‘development' in decadence (Maoism) as its evolution was taking place in a situation that made it impossible for new powers to emerge and catch up with the others, as had been the case in the ascendant period. China therefore sold itself to the highest bidder within the context of the imperialist division of the world into two poles during the Cold War (1945-89). Isolation from the world market, integration into the Soviet bloc and the massive aid granted by the latter made Chinese growth possible - although only modestly since at less than half the world growth rate. However it was relatively better than that of India and the rest of the Third World. In fact, as India was only partly excluded from the world market and as it had put itself forward as leader of the "non-aligned countries"[5], it paid the price in terms of its economic growth, which was even lower than that of Africa during the same period (1950-73). The implosion of the big imperialist blocs after the fall of the Berlin wall (1989) and the continued decline of American leadership in the world have removed the constraints of international domination by the two imperialist poles and have given more latitude to every country to give free rein to its own interests.

[1] "The period of capitalist decadence is characterised by the impossibility of any new industrial nations emerging. The countries which didn't make up for lost time before World War I were subsequently doomed to stagnate in a state of total underdevelopment, or to remain chronically backward in relation to the countries at the top of the sandcastle. This has been the case with big nations like India or China, whose ‘national independence' or even their so-called ‘revolution' (read the setting up of a draconian form of state capitalism) didn't allow them to break out of underdevelopment or destitution. (...) The inability of the under-developed nations to lift themselves up to the level of the most advanced countries can be explained by the following facts: 1) The markets represented by the extra-capitalist sectors of the industrialised countries have been totally exhausted by the capitalisation of agriculture and the almost complete ruin of the artisans. (...) 3) Extra-capitalist markets are saturated on a world level. Despite the immense needs of the third world, despite its total destitution, the economies which haven't managed to go through a capitalist industrialisation don't constitute a solvable market because they are completely ruined. 4) The law of supply and demand works against any development of new countries. In a world where markets are saturated, supply exceeds demand and prices are determined by the lowest production costs. Because of this, the countries with the highest production costs are forced to sell their commodities at reduced profits or even at a loss. This ensures that they have an extremely low rate of accumulation and, even with a very cheap labour force, they are unable to realise the investments needed for the massive acquisition of modern technology. The result of this is that the gulf which separates them from the great industrial powers can only get wider. (...) 6) Today, modern industrial production requires an incomparably more sophisticated technology than in the last century; this means considerable levels of investment and only the developed countries are in a position to afford them." (International Review n°23, 1980, ‘The Proletarian Struggle under Decadent Capitalism', Development of New Capitalist Units, pg 23-24).

[2] Maddison, OECD, 2001: 283, 322.

[3] World trade developed very rapidly after 1945, even more so than in the ascendant period as trade increased five-fold between 1948 and 1971 (23 years) whereas it increased only by a factor of 2.3 between 1890 and 1913 (also 23 years). So growth in world trade was twice as much during the post-war boom than during the strongest period in the ascendant phase (Source: Rostow, The World Economy, History and Prospect, University of Texas Press, 1978: 662). So, in spite of this incredible growth in world trade, the percentage exports of the wealth produced in the world was less than the level reached in 1913 and even than that of 1860. The developed countries exported no more in 1970 than they did a century earlier. This is a definite indication of growth centred on the national framework. Moreover, the evidence of a strong recovery in international trade after 1945 is really less marked than it seems from the graph. In fact an increasing proportion of it did not involve real sales but rather exchange between subsidiary companies because of the increase in international division of labour: "according to the estimates made by the UNCTAD, the multinational companies alone account for two-thirds of world trade at present. Exchange between subsidiaries of the same group comprise a half of world trade." (Bairoch Paul, Victoires et déboires, III: 445). This reinforces our general conclusion that decadence is characterised essentially by a general withdrawal on the part of each country into its national framework and not, as in the ascendant period, by expansion and prosperity based on the relentless conquest of the world.

[4] All data concerning DFI is taken from Bairoch Paul, 1997, Victoires et déboires, III: 436-443.

[5] From 18th to 24th April 1955 in Bandung on the Indonesian island of Java, there took place the first Afro-Asian conference, in which twenty-nine countries took part. Most of them had recently lost their colonial status and all of them belonged to the Third World. The summit was called on the initiative of the Indian Prime Minister, Nehru, who was eager to create on the international scene a group of powers who would remain outside the two big blocs and the logic of the Cold War. However these so-called "non-aligned" countries never really managed to be "independent" or to steer clear of the confrontation between the two large (American and Soviet) imperialist blocs. So this movement included countries that were pro-West, such as Pakistan or Turkey, and others that were pro-Soviet, such as China and North Vietnam.

Part 2: East Asia’s place in the history of capitalist development and its current trajectory

- 4955 reads

The see-saw evolution of East Asia historically (1700-2006)

We have situated the development of East Asia within the historic context of the ascendant and decadent phase of capitalism and also within the framework of the development of state capitalism and the region's integration into the imperialist blocs during the decadent phase. We must now try to understand why this region has managed to reverse its historic trend towards marginalisation. The table below shows that in 1820 almost half the wealth produced in the world (48.9%) was concentrated in India and China but that by 1973 the figure was no more than 7.7%. The colonial yoke, followed by capitalism's entry into its decadent phase reduced India and China's share of world GDP six-fold. In other words, when Europe and the new states were developing, India and China were retreating. Today it is the exact opposite; whereas the developed countries are in crisis, East Asia is recovering to the point that in 2006 it raised its contribution to the production of international wealth to 20%. So there is a definite see-saw development historically: when the industrial countries have strong growth, Asia experiences a downturn and when the crisis takes a permanent hold in the developed countries, Asia experiences an economic boom.

|

Table 4 : The share of different world zones in % of world GDP |

||||||||

|

1700 |

1820 |

1870 |

1913 |

1950 |

1973 |

1998 |

2001 |

|

|

Europe and "new countries" (*) |

22,7 |

25,5 |

43,8 |

55,2 |

56,9 |

51 |

45,7 |

44,9 |

|

Rest of the world |

19,7 |

18,3 |

20,2 |

22,9 |

27,6 |

32,6 |

24,8 |

(°) |

|

Asia |

57,6 |

56,2 |

36,0 |

21,9 |

15,5 |

16,4 |

29,5 |

|

|

India |

24,4 |

16,0 |

12,2 |

7,6 |

4,2 |

3,1 |

5,0 |

5,4 |

|

China |

22,3 |

32,9 |

17,2 |

8,9 |

4,5 |

4,6 |

11,5 |

12,3 |

|

Rest of Asia |

10,9 |

7,3 |

6,6 |

5,4 |

6,8 |

8,7 |

13,0 |

(°) |

|

(*) New countries = USA, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand (°) = 37,4 : Rest of the world + Rest of Asia |

||||||||

|

Source : Angus Maddison, L'économie mondiale, OCDE, 2001 : 280 |

East Asia's development after World War II

This see-saw movement is also evident in the development of China's growth rate in relation to the rest of the world following World War II. Tables 3 and 5 (below) show that when the developed countries experienced sustained growth, India and China lagged behind: between 1950 and 1973, Europe did twice as well as India, Japan did three times as well as China and four times as well as India and the growth of the latter two countries was less than half of the world rate. But then the situation was reversed: between 1978 and 2002; the average annual growth rate in Chinese GDP per head was more than four times higher (5.9%) than average world growth (1.4%) and India increased its GDP fourfold although global GDP increased by only 2.5% between 1980 and 2005.

|

Table 5 : Mean annual growth rates of per capita GDP (in %) |

||

|

|

1952-1978 |

1978-2002 |

|

China (corrected for over-estimates) |

2,3 |

5,9 |

|

World |

2,6 |

1,4 |

|

Source : F. Lemoine, L'économie chinoise, La Découverte : 62. |

So it was only when the central capitalist countries went into crisis that the economies of India and China took off. Why? What is behind this see-saw dynamic? Why is it that, whereas the rest of the world is sinking into crisis, East Asia is experiencing renewed growth? How can we explain this episode of marked expansion in East Asia while the economic crisis continues at an international level? This is what we will now examine.

The return of the economic crisis reveals the failure of post-war palliatives

The return of the economic crisis at the end of the 1960s swept away all the growth models that had flourished in the world after the Second World War: in the East the Stalinist model, in the West the Keynesian model and the national-military model in the Third World. It laid low the pretensions of each one, to have found a solution to the insoluble contradictions of capitalism. The aggravation of the crisis throughout the 70s marked the failure of neo-Keynesian measures in the OECD countries, it led to the implosion of the Eastern bloc the following decade and it revealed the impotence of all "third worldist" alternatives (Algeria, Vietnam, Cambodia, Iran, Cuba, etc). All the models that supplied illusions during the halcyon days of the post-war boom fell under the buffeting of repeated recessions, so showing that they were in no way a means to overcome the intrinsic contradictions of capitalism.

The consequences of this failure and the response to it were very different. From 1978-80 the western countries redirected their policies towards an unregulated state capitalism[1] (the neo-liberal turn as the media and leftists called it). On the other hand, the rigidity of Stalinist state capitalism meant that a similar process could occur in the Eastern countries only after this system collapsed. It was also due to the unbearable pressure of the economic crisis that various countries and "models" in the third world were dragged down either into endless barbarism (Algeria, Iran, Afghanistan, Sudan, etc). Others simply went bankrupt (Argentina, several African countries, etc) or ran into difficulties that destroyed their pretensions to be successful models (the Asian tigers and dragons). However, at the same time a few countries in East Asia, such as India, China and Vietnam, managed to introduce gradual reforms which brought them into the bosom of the world market by allowing them to enter into the international round of accumulation that began in the 1980s.

These different responses had different results and we will restrict ourselves here to what happened in the Western countries and in East Asia. We should point out that, just as the reappearance of the crisis showed itself first in the central countries and then reached the peripheral countries, it is the economic upturn that took place in the developed countries at the beginning of the 80s which determined the place taken by the countries of the East Asian sub-continent in the international round of accumulation.

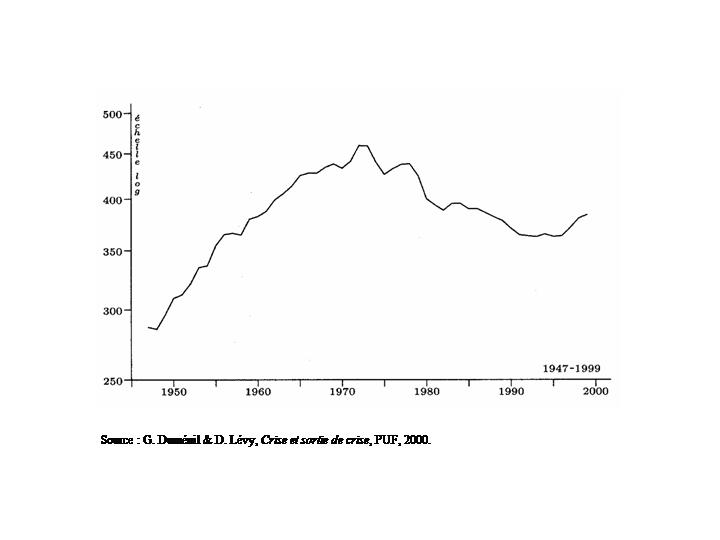

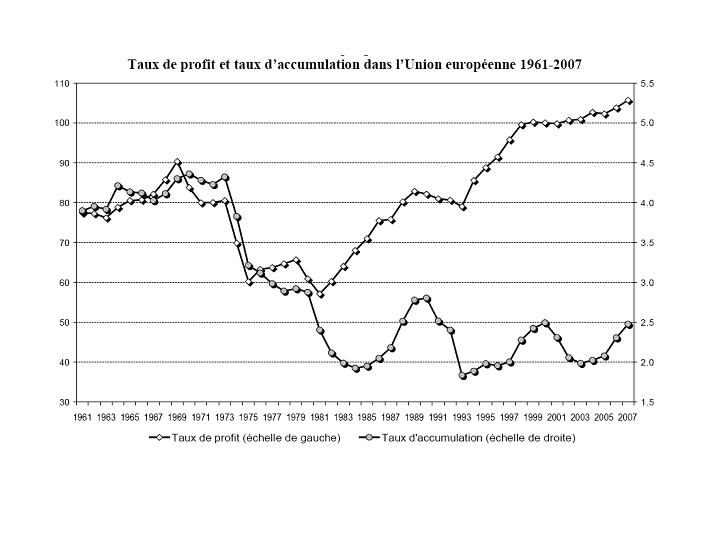

The arrival of unregulated State Capitalism and "deformed" globalisation

None of the neo-Keynesian measures for economic recovery used during the 1970s managed to improve the profit rate, which was halved between the end of the 1960s and 1980 (see graph 6 below[2]). This constant fall in the profitability of capital led many firms to the brink of bankruptcy. States that had already run into debt in order to support the economy almost reached the point of suspending payments. The transition to unregulated state capitalism and a "deformed" globalisation was the consequence of this situation of virtual bankruptcy at the end of the 1970s. The essential axis of this new policy was a massive and frontal attack against the working class in order to increase the profitability of capital. From the beginning of the 1980s the bourgeoisie launched a series of massive attacks against the living and working conditions of the working class: they did away with a number of Keynesian recipes and obliged the workforce to compete internationally through delocalisation and the introduction of international competition (the loosening of regulation). This enormous social regression produced a spectacular recovery in the rate of profit to the point where it even exceeded that achieved during the post-war boom (see graph 6 below).

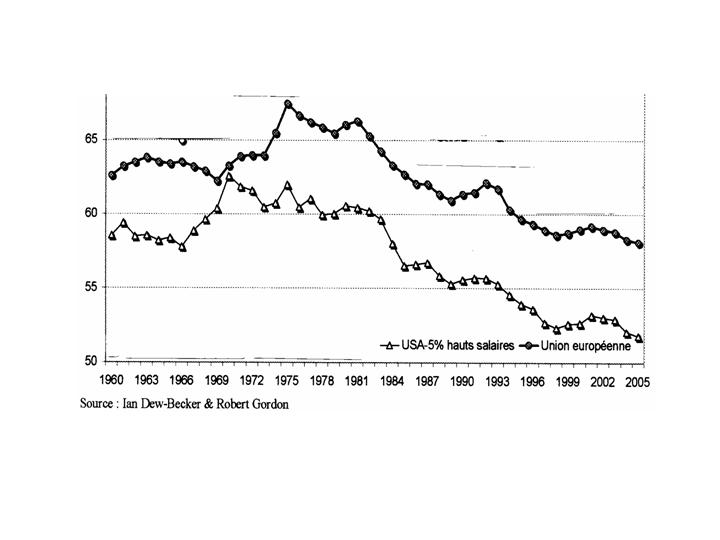

Graph 3 below demonstrates this policy of eliminating regulation whole sale, a policy that enabled the bourgeoisie to lower the wage mass as a proportion of GNP by +/-10% internationally. This reduction is no more than the concretisation of the spontaneous tendency towards an increase in the rate of surplus value or the rate of exploitation of the working class[3]. The graph also shows the stability of the rate of surplus value in the years preceding the 1970s. This stability, together with a significant increase in productivity, was behind the post-war boom. The rate dropped during the 70s as a result of pressure from the class struggle, which had reappeared massively from the end of the 1960s.

This reduction of working class wages as a proportion of total production is really much greater than it seems from the graph because the latter includes the salary of all categories, including that of the bourgeoisie[4]. Although income was modest during the post-war boom, it began to increase again after them. Thereafter it was the workers who were the most badly affected by wage reductions. In fact, statistics compiled on the basis of social category show that for many sectors of workers - the less qualified on the whole - this reduction was so great as to lower their wages to their 1960 level. This was already the case for production workers in the United States (weekly income). Although their real wages almost doubled between 1945 and 1972, they then dropped again to stabilise at their 1960 level.

For a quarter of a century we have witnessed a massive and increasingly generalised tendency towards the absolute pauperisation of the working class internationally. On average wages' share of GDP fell dramatically by between 15% and 20%. In addition to this, workers suffered a serious decline in their living and working conditions. As Trotsky said at the 3rd Congress of the CI: "The belief was held that the theory of the pauperisation of the masses had been eliminated at the contemptuous whistle of bourgeois eunuchs engaged in their university debates and by the opportunist intellectuals of socialism. Now we are experiencing, not only social pauperisation but also psychological and biological impoverishment in all its hideous reality". In other words, what Keynesian state capitalism conceded during the post-war boom - because real wages more than tripled between 1945 and 1980 - unregulated state capitalism is taking back at break neck speed. With the exception of the post-war interlude, the whole trajectory confirms the analysis of the International Communist Current and the Communist Left according to which there can no longer be real, and above all lasting reforms in the decadent phase of capitalism.

This huge wage reduction had two consequences. On the one hand, it made possible an enormous rise in surplus value which enabled the bourgeoisie to re-establish its profit rate. In fact it attained, and even overtook, the level it had reached during the post-war boom (see graph 6). On the other hand, by drastically reducing wage demand by between 10% and 20%, it considerably lowered the relative number of solvent markets at an international level. This led to a serious intensification of the international crisis of over-production and to a fall in the accumulation rate (the growth of fixed capital) to an historic low. (See graph 6). This two-pronged movement; the search for greater profitability in order to increase the profit rate and, at the same time, the need to find new markets to get its production circulating, gave rise to the globalisation phenomenon which appeared in the 1980s. According to the leftists and other "alternative-worldists", globalisation is a consequence of the domination of (bad) unproductive finance capital over the (good) productive industrial capital. According to the leftist version of the argument, finance capital should be abolished and they misuse Lenin's Imperialism the Highest Stage of Capitalism in order to justify what they say. According to the anti-globalist or left social democratic brand, it should rather be controlled and taxed (Tobin tax). In fact their claims as to the cause of globalisation are completely false.

The historic significance of globalisation today

In fact all that is written about globalisation, whether by the right or the left, the anti-globalists or the leftists, presents it as a remake of the conquest of the world by means of trade relationships. Often well-known passages from the Communist Manifesto are quoted, where Marx refers to the progressive role of the bourgeoisie and to the global expansion of capitalism. It is presented as a vast process of dominating and commercialising all aspects of life through capitalist relations. We are even told that it will be the second globalisation after that of 1875-1914.

According to this view of the current phenomenon of globalisation, the whole period from the First World War to the 1980s was no more that a huge interlude, either isolationist (1914-45) or regulated (1945-80). It was a period that made it possible to carry out social policies in favour of the working class - according to the leftists - or which prevented capitalism from entirely fulfilling its potential - according to the liberals. The "let's get back to the good old days" of the former is the mirror image of the "let's get rid of regulation" and "let's liberalise to the hilt" of the latter, who claimed that by giving "complete freedom and power to the markets", the whole world would reach growth rates equal to those in China. If we would only accept the working conditions and the wage levels of the Chinese workers, we would throw open the gates to a paradise of strong growth. The way the question is presented by the leftists or the liberals could not be further from the truth. There are several reasons for this and they can be summed up by showing that the roots of the present globalisation phenomenon has nothing in common with capitalism's tendency to spread internationally in the 19th century:

- The first period of globalisation (1880-1914) corresponded to the formation of the world market and the profound penetration of its commercial relations throughout the world. It expressed the geographic extension of capitalism and its domination at a world level; it constantly increased the level of accumulation by raising wages and international demand. Whereas the dynamic of 19th century swept capitalism up into a whirlwind of ever greater heights, the present globalisation is no more than a vicissitude of capitalism, which has run out of steam as far as its international accumulation and growth rate is concerned. It is in decline, it depresses growth and lowers the wage mass, so reducing solvent markets. Today, globalisation and the loosening of regulation are just measures taken to palliate the devastating effects of the historic crisis of capitalism. The "neo-liberal" policies of slackening restraints and globalisation are no more than the umpteenth attempt to overcome the failure of previous palliatives, whether Keynesian or neo-Keynesian. Today there is no trace of the triumphant capitalism of the 19th century; the system is continuing the slow agony that began in the 1970s. The fact that the constriction of the international circle of accumulation since the 1970s includes the local development of the Asian sub-continent in no way changes the deformed nature of this globalisation because the development involves only part of the world, can only last for a limited period of time and is the corollary of a vast and massive social regression at an international level.

- The first period of globalisation marked the conquest and penetration of capitalist relations of production throughout the world, drawing in its wake more and more new nations and strengthening the domination of the old colonial powers. Today's trajectory is essentially limited to the Asian sub-continent and weakens and endangers the economies of both the developed countries and of other Third World countries. Whereas the first globalisation marked the geographic extension and deepening of capitalist relations, today it is no more than an aberration in the general process of worsening international crisis. It develops only a part of the world - East Asia - while leaving the other countries adrift. Moreover, this interlude of very localised development in the Asian sub-continent can only last as long as the conditions that generate it. By now its days are numbered (see below and the following sections of this article).

- Whereas the first globalisation period was accompanied by a general rise in the living conditions of the working class with a doubling of real wages; the current globalisation brings with it massive social regression; the lowering of wages, absolute pauperisation for tens of millions of proletarians, the massive degradation of working conditions, a huge increase in the rate of exploitation, etc. Whereas the first globalisation brought progress for humanity, the current one spreads barbarism throughout the world.

- The first period of globalisation integrated a larger and larger mass of workers into relations of production based on wage labour. However the current one eliminates jobs and undermines the social tissue in those countries and among those sections of the international working class that are the most experienced, even if it does give rise to a young and inexperienced proletariat in the peripheries. Although the first period of globalisation tended to unify conditions and solidarity within the working class, the current one increases competition and "every man for himself" in the context of generalised decomposition in social relations.

For all these reasons, it is quite wrong to present the current globalisation phenomenon as a remake of the period of capitalism's glory. It is also quite wrong to do so by quoting well-known passages from the Communist Manifesto, in which Marx describes the progressive role of the bourgeoisie in his time. Capitalism has now had its day; it has produced the 20th century, which was the most barbarous in the whole history of humanity. Nor do its social relations of production work towards human progress; they rather drag humanity down more and more into barbarism and the risk of global ecological destruction. In the 19th century the bourgeoisie was a progressive class which developed the productive forces. Today it is obsolete; it is destroying the planet and is spreading nothing but misery, to the point that it has even hocked the future of the world. This is not really globalisation, it is more correct to call it deformed globalisation.

The political significance of globalisation and the loosening of regulatory restraints

The media and left critics characterise the policies carried out by the bourgeoisie since the 1980s that are aimed at relaxing regulation and liberalising, as leaning towards neo-liberalism and as globalisation. In fact these labels are charged with an ideological content that is a complete mystification. Firstly, the so-called "neo-liberal' loosening of regulation was enacted at the initiative and under the control of the state, and it by no means entails a "weak state" and control by the market alone, as is claimed. Secondly, as we have shown above, globalisation today has nothing to do with what Marx was describing in his writings. It corresponds to a stage in the deepening of the crisis internationally and not to a real and progressive extension of capitalism as was the case during the ascendant period of the system. It is a deformed globalisation. This obviously does not exclude a brief and localised development of commercial relations and an increase in the number of wage earners (as in East Asia, for example). The fundamental difference is that this process is taking place in a dynamic that is radically different from that which prevailed during the ascendant period of capitalism.

These two policies (unregulated state capitalism and deformed globalisation) are not the expression of a capitalist renewal or the setting up of a new "finance capital', as the vulgar leftists and anti-globalists claim. Above all, they reveal the worsening of the world economic crisis in that they proclaim the failure of all the measures of classic state capitalism that were used previously. At the same time, the constant appeals on the part of the bourgeoisie to broaden and generalise these policies even more, is equally a clear admission of their failure. In fact, more than a quarter of a century of unregulated and globalised capitalism has proved unable to rectify the economic situation internationally. For the whole time that these policies were in place, the international per capita GDP has continued to decline decade after decade, even if at a local level and for a limited time, and this has enabled East Asia to benefit and so to experience spectacular growth.

The arrival of unregulated state capitalism and deformed globalisation is a clear expression of capitalist decadence

The persistence of the crisis and the continual fall in the rate of profit throughout the 70s has damaged the profitability of capital and of businesses. Towards the end of the 70s the latter got badly into debt and many of them are on the brink of bankruptcy. Together with the failure of neo-Keynesianism to re-launch the economy, this situation of bankruptcy obliged the bourgeoisie to abandon Keynesian measures in favour of unregulated state capitalism and a deformed globalisation, whose main purpose was to raise the rate of profit and the profitability of companies and to open up the international market. This re-orientation of economic policy on the part of the bourgeoisie marked, more than anything, a stage in the worsening of the crisis internationally. It was not the beginning of a new period of prosperity, made possible by the "new economy", as the media is constantly telling us. The gravity of the crisis was such that the bourgeoisie had no other choice but to return to more "liberal" measures, although in reality these only accelerated the crisis and the slowing of growth. Twenty-seven years of unregulated state capitalism and globalisation have resolved nothing but have rather aggravated the economic crisis.

There are two pillars of deformed globalisation, which accompanied the setting up of unregulated state capitalism from 1980 onwards. Firstly, the frantic search for places where production can take place with low labour costs, in order to raise companies' profit rate (sub-contracting, delocalisation, etc). Secondly, the desperate hunt by each country for demand that is "external" to it in order to attenuate the lessening of demand coming from wages within the country, a demand that has been reduced because of the austerity measures aimed at raising the profit rate. This policy worked to the good of East Asia, which was able to adapt and take advantage of this development. From then on, the spectacular growth in East Asia, rather than helping to raise international economic growth, has in fact been an added factor in depressing final demand by reducing the wage mass world-wide. In this way, these two policies have greatly contributed to the worsening of the international crisis of capitalism. This can be clearly seen from the graph below, which shows a constant and coherent relationship between the development of production and that of world trade since the Second World War. This is interrupted only in the 1990s when, for the first time in about sixty years, there is a divergence between world trade, which takes off, and production, which remains flat.

Therefore trade with the Third World, which had halved during the post-war boom, took off again from the 1990s following globalisation. However it involved only a few countries in the Third World, those that were transformed into "workshops of the world" turning out goods with low wage costs[5].

The fact that the recovery of world trade and of percentage exports since the 1980s is not accompanied by an increase in economic growth, is a clear illustration of what we are saying: unlike the first period of globalisation in the 19th century, which extended production and increased the wage mass, the current one is deformed in that it lowers the wage mass and restrains the basis of accumulation internationally. The fact that the current "globalisation" boils down to a bitter struggle to reduce production costs by savagely lowering real wages, shows that capitalism no longer has anything to offer humanity except misery and growing barbarism. The so-called "neo-liberal globalisation" has nothing to do with a renewal of world conquest by triumphant capitalism as in the 19th century, but reveals above all the bankruptcy of all the palliatives employed to confront an economic crisis that is leading capitalism slowly but inexorably towards bankruptcy.

[1] We refer the reader to our articles on this question for a better understanding of the terminology used here.

[2] In n°128 of this Review, we published two graphs showing the evolution of the profit rate over a century and a half in the United States and France. They show clearly this halving of the profit rate between the end of the 1960s and 1980. It is one of the most spectacular falls in the rate of profit in the whole history of capitalism and it was an international phenomenon.

[3] The rate of surplus value is no more than the rate of exploitation which relates the surplus value (SV) appropriated by the capitalist to the mass of wages (VC = Variable Capital) which he pays out to the wage workers. Rate of exploitation = Surplus value/Variable Capital.

[4] This graph is taken from the study carried out by Ian Dew-Becker and Robert Gordon, Where did the Productivity Growth Go? Inflation Dynamics and the Distribution of Income, Washington DC, September 8-9 2005. It is available from the internet at the following address: zfacts.com/metaPage/lib/gordon-Dew-Becker.pdf. The graph shows the evolution of wages as a percentage of GDP. It includes all wages for the European Union and all wages less the top 5% for the United States".

[5] It is because these goods are "low cost" that exports, as a percentage of production remained high between 1980 (15.3%) and 1996 (15.9%). In fact they are even higher if calculated, not in value, but in volume: 19.1% in 1980 and 28.6% in 1996.

Part 3: East Asia and the international cycle of accumulation

- 3218 reads

It was thus a twofold movement that enabled East Asia to infiltrate to its own advantage the international cycle of accumulation from the 1990s. On the one hand, the economic crisis forced India and China to abandon their respective Stalinist and nationalist models of state capitalism. On the other hand, the development of globalisation offered East Asia the opportunity to re-enter the world market by offering a place for the investments and delocalisation of the developed countries that were looking for a low-cost workforce. This twofold movement explains the see-saw evolution, described above, between world growth, which tends to ebb constantly, and strong localised growth in the Asian sub-continent.

So it is the deepening of the capitalist crisis that is at the heart of this blockage in international accumulation that has enabled East Asia to find a place as workshop of the world. It accomplishes this by accepting the investments, delocalisation and sub-contracts coming from the developed countries, which are looking for pools of low-cost labour power. It then exports back to these countries consumption goods produced for low wages. At the same time, to the Asian nouveau riche it sells goods, to which a great deal of value has been added in Asia, as well as luxury goods from the developed countries.

The growth in East Asia signals the crisis and not the renewal of capitalism

So the failure of the neo-Keynesian measures employed during the 70s in the central countries marked a significant stage in the intensification of the international crisis. This failure was behind the abandoning of Keynesian state capitalism in favour of a less regulated variety, whose main axis was a massive and frontal attack against the working class in order to raise the profit rate which had been halved since the end of the 1960s (see graph 6). This immense social regression took the form of a systematic policy of international competition in terms of wage levels. By managing to infiltrate this new international division of labour and wages, India and China gained a great deal from it. In fact, whereas capital was withdrawn almost totally from the peripheral countries during the post-war boom, today about a third is invested there and it is mainly concentrated in a few Asian countries. This allows these two countries to set themselves up as a base for the production and the re-exportation of goods assembled in factories that are anyway fairly productive but whose social conditions are appropriate to the early years of capitalism. This is basically what is behind the success of these countries.

Since the 1990s, India and China have received a huge amount of capital and delocalised industry, which transformed them into international workshops and inundated the world market with their low cost goods. In the previous period the wage differential in their obsolete factories, together with protectionist policies, made it impossible for the produce of under-developed countries to compete on the markets of the central countries. Today, however, liberalisation makes it possible to produce at very low wage costs in productive delocalised factories and so to make inroads into a number of productive sectors of the western market.

Therefore, the spectacular growth in East Asia is not the indication of a capitalist renewal but is rather a temporary upturn within a slow international decline. The fact that this aberration has been able to dynamise a significant part of the world (India and China) and even contributes to world growth is no more than an apparent paradox when viewed in the context of the slow international development of the crisis and the historic period of capitalist decadence[1]. It is only by taking an overview and placing each specific event in its global context that we can make sense of it and understand the situation. Just because we find ourselves on a bend in the river, it does not mean that we can conclude that the sea flows towards the mountain[2].

The conclusion that emerges from the evidence and that needs to be stressed, is that growth in East Asia is in no way an expression of a renewal of capitalism, it in no way erases the deepening of the crisis internationally and in the central countries in particular. On the contrary, it is part of its mechanism, one of its stages. The apparent paradox is to be explained by the fact that East Asia was there at the right moment to benefit from a phase in the deepening of the international crisis, which enabled it to become the workshop of the world offering low wage costs.

Asian growth accelerates the depression internationally

This recent blockage in international accumulation accentuates the economic dynamic towards international depression because its buoyancy greatly increases overproduction while depressing final demand in the wake of a relative reduction in the wage mass world-wide and the destruction of numerous uncompetitive regions or sectors throughout the world.

Marx has taught us that there are fundamentally two ways to improve the growth rate; either from above by increasing productivity through investing in new machinery and production processes, or else from below by reducing wages. As the re-emergence of the crisis at the end of the 1960s was expressed in an almost uninterrupted decline in productivity increases, the only remedy for the profit rate was a massive attack on wages[3]. The graph below shows this trajectory towards depression very clearly. During the post-war boom the rate of profit and accumulation developed in parallel and were at a high level. From the end of the 60s the rate of profit and accumulation halved. Following the switch to unregulated state capitalist policies from the 80s, the profit rate rose dramatically and even overtook the level attained during the post-war boom. However, although the rate of profit rose, the rate of accumulation did not follow it and remained at a very low level. This is a direct result of the weakness in final demand due to the huge reduction of the wage mass, which is behind the rise in the profit rate. Today capitalism is engaged in a slow recessive spiral: its businesses are profitable but they work on a foundation that is increasingly narrow because overproduction imposes limits on the base of accumulation.

This is why the present growth in East Asia can by no means be seen as an Asian version of the post-war boom or as a renewal of capitalism globally but shows rather that it is sinking deeper into crisis.

Conclusion

The origin, the core and the dynamic of the crisis lies in the central countries. The slow down in growth, unemployment, the decline in working conditions are phenomena that greatly pre-date the development in East Asia. It was precisely the consequences of the crisis in the developed countries that restricted international accumulation and so enabled Asia to become the workshop of the world. This new constriction in its turn contributes to the economic trajectory towards depression in the central countries because it increases over-production world-wide (supply) and depresses the soluble markets (demand) by lowering the wage mass internationally (an essential economic factor) and by destroying a large number of the less competitive economies in the Third World (a factor that is marginal at an economic level but tragic at a human one).

The re-emergence of the historic crisis of capitalism from the end of the 1960s, its intensification throughout the 1970s, together with the failure of the neo-Keynesianism palliatives in operation at the time, cleared the way for unregulated state capitalism. This, in its turn, produced the deformed globalisation of the 1990s and certain countries have been able to play the role of workshops offering low wages. This is the basis of the spectacular growth in East Asia which, together with the crisis of the Stalinist and nationalist model of autarchic development, enabled it to infiltrate the new cycle of international accumulation at the right moment.

C.Mcl

[1] In fact, world GDP per head has constantly declined decade after decade since the 80s: 3.7% (1960-69), 2.1% (1970-79), 1.3% (1980-89), 1.1% (1990-99) and 0.9% for 2000-2004. However, at the moment it seems likely that, for the first time, the average for the decade from 2000 may be significantly higher than that of the previous decade. Unless, that is, a serious recession occurs before the end of this decade, an eventuality which is likely enough. This improvement can, to a large extent, be attributed to the economic dynamism in East Asia. However, this leap is very relative because, if we look closely at the parameters, we can see that, since the "new economy" (2001-2002) crashed, world growth has been based mainly on large mortgage debts and an American balance of trade that has reached record lows. In fact the American property market (also that in several European countries) has greatly sustained growth through enormous debts based on re-negotiating mortgages (made possible because of the policy of low interest rates in order to restore growth). This has reached such a point that there is now talk of a possible property crash. On the other hand the public deficit, especially in terms of trade, has reached record levels and this has also greatly sustained world growth. So, when we look more closely, this probable improvement in the decade from 2000 will have been obtained by heavily mortgaging the future. (Note: this article was written before the sub-primes crisis broke out).

[2] This kind of upturn is hardly surprising and has even been a fairly frequent occurrence during the decadence of capitalism. Throughout this period the essence of the bourgeoisie's policies, those of state capitalism specifically, has been to intervene in the operation of its economic laws in order to try and save a system which tends inexorably towards bankruptcy. This is what capitalism did on a large scale during the 30s. At the time, hard state capitalist policies as well as massive re-armament programmes created the temporary illusion that the crisis was under control and even that prosperity was making a come-back: the New Deal in the United States, the Popular Front in France, the De Man plan in Belgium, the Five Year Plans in the USSR, Fascism in Germany, etc.

[3] We refer the reader to the article in n°121 of this Review, which describes this process and gives all the empirical data.