International Review no.133 - 2nd quarter 2008

- 4301 reads

Anti-fascism: the road to the betrayal of the CNT

- 4983 reads

In the previous articles in this series[1] we have shown how the FAI tried to stop the definitive integration of the CNT into the structures of capitalism. This effort failed. The FAI's insurrectional policy (1932-33) which tried to correct the CNT's serious opportunist deviations, as well as those of the FAI itself, which were expressed through their active support for the creation of the Republic in 1931[2]. led to a terrible haemorrhaging of the forces of the Spanish proletariat, by squandering them in dispersed and desperate struggles.

In 1934 however there was a fundamental change: the PSOE made a spectacular about face and, led by Largo Caballero, along with its companion union , the UGT, raised the flag of the "revolutionary struggle" pushing the workers of Asturias into the dreadful trap of the October insurrection. The Republican state used a new orgy of death, torture and prison deportations, which matched the savage repression meted out in previous years, to liquidate this movement.

This change should not be seen through the prism of events in Spain. It needs to be clearly placed in the evolution of the world situation. Following Hitler's rise to power in 1933, the massacres of workers became more widespread. In Austria the Social Democrats -the left hand of Austrian capital- pushed the workers into a premature insurrection; a defeat that allowed the right hand - the supporters of Nazism- to perpetuate a pitiless massacre. 1934 was also the year in which the USSR signed accords with France integrating it with full honours into imperialist "high society" something that was formally recognised by its admission into the League of Nations (the predecessor of the UN). In this year the Communist Party also made a radical change: the "extremist" policy of the "Third Period", a crude parody of "class against class", was replaced overnight by the "moderate" policy of helping the Socialists to form the inter-classist Popular Fronts that subordinated the proletariat to the "democratic" bourgeois fractions in order to achieve the "ultimate" aim of "stopping the rise of fascism".

Workers Alliances, tool of the anti-fascist front

This international atmosphere provided a context within which the CNT, as well as the FAI, was driven towards full integration into the capitalist state by its adoption of anti-fascism along with the other "democratic" forces.

Anti-fascist ideology was turned into a whirlwind that smashed the last reserves of proletarian consciousness and sucked up proletarian organisations whilst leaving those who managed to maintain a class position in terrible isolation. This ideology in the conditions of the period - the defeat of the proletariat, development of strong regimes as a way of installing State capitalism - best served the "democratic" bourgeoisie preparations for the march towards the generalised war the broke out out in 1939; for which the Spanish struggle from 1936 was the prelude.

We are not going to analyse this ideology here,[3] rather we are going to investigate how its adoption effected the CNT and FAI and sucked them into betraying the proletariat in 1936. The way was opened by the Workers Alliances. These Alliances were presented as the means for advancing workers unity through agreements and cartels between different organisations.[4] The lure of "workers' unity" led to the trap of "anti-fascist" unity which lined up the proletariat behind the defence of bourgeois democracy in order, supposedly, "to stop the rise" of rampant fascism. The Madrid Workers' Alliance (1934) openly proclaimed: "first and foremost, the struggle against fascism in all its forms and the preparation of the working class for the implantation of federal socialist peace in Spain, is the most pressing need".[5]

The opposition unions of the CNT[6] tried to present themselves as unions pure and simple, leaving behind "the anarchist nonsense" as they said, by actively participating in the Workers Alliances, hand in hand with the Stalinist PC, the organisations of the Left Opposition, and from 1934, the UGT-PSOE. Within the CNT and FAI on the other hand there were strong hesitations which undoubtedly expressed a proletarian instinct.

These hesitations however were progressively dissipated due to widespread poisonous atmosphere generated by anti-fascism, as well as by the spade work carried out by wide sections of the CNT itself and the Socialist Party's efforts at seduction.

The CNT's Asturian Region was at the forefront of the struggle to defeat this resistance. The October 1934 Asturian insurrection was prepared before hand by a pact between the regional CNT and UGT-PSOE.[7] The PSOE hardly took part in the arming of the strikers and marginalised the CNT, the Asturian region nevertheless stubbornly preserved the Workers Alliance. At the decisive Zaragoza Congress,[8] this region's delegate recalled that: "a comrade wrote an article in "CNT"[9] recognising the necessity for the Alliance with the Socialists in order to carry out the revolution. A month later another plenum was held and this called for sanctions to be applied in relation to the article. At the time we said we were in favour of the criteria used in this article. And we affirm our point of view about the advisability of drawing the socialists from power in order to make them take the revolutionary road. We sent them communications against the anti-socialist position taken by the National committee in a manifesto".[10]

For his part Largo Caballero[11] in a speech in Madrid put out feelers towards the CNT and FAI "[I say] to those workers nuclei that we were wrong to struggle against them. Their purpose, like ours, is a regime of social equality. They accuse us of nurturing the idea that the state is above the working class. We do not think they have really studied our ideas. We want the disappearance of the state as a means of oppression. We want to turn it into a merely administrative entity" (quoted in Olaya, op cit. Page 866).

As we can see this seduction was pretty crude. He appears to be talking about the "disappearance of the State" but what was being said in reality is that the state can be reduced to a "merely administrative entity". An illusion also used by democrats, who tell us that the democratic state is not "a means of oppression" but rather an "administration". According to this myth only dictatorial states are "organs of oppression".

This flattery, despite coming from such an unattractive individual as Largo Caballero[12] increasingly bedazzled the CNT and FAI. In 1934 a Plenum was held on fascism which according to the report began by clearly denouncing the PSOE and the UGT but ended up leaving the door open to an understanding with them: " This is not to say, of course, that if these organisations (the UGT and PSOE) were pushed by circumstances to carry out an insurrectional action we would be passive by-standers, nothing of the sort (...) at such a moment we would be able to give the anti-fascist movement the stamp of our principles, our libertarian principles".[13]

Anarchism -along with marxism- has always defended the principle that all states, whether democratic or totalitarian, are authoritarian organs of oppression. This principle was spectacularly thrown into the dustbin with the idea of the possibility of "stamping" the anti-fascist movement with the same principle, a movement whose very foundation is to choose, to defend, the democratic form of state, that is, the most devious and cynical variant of this authoritarian organ of oppression!

This progressive abandoning of principles caused by trying to combine antagonistic positions spread increasing confusion, undermined convictions and with increasing force opened the workers' movement up to "anti-fascist unity". The opposition unions added to this from 1935 by beginning a campaign aimed at drawing closer to the CNT through the idea of re-unification based upon anti-fascist unity with the UGT.

This pressure became increasingly powerful. Peirats shows that "the Asturian drama had been nurturing the Alliancists programme within the CNT. Alliancism began to be propagated in Catalyuna one of the confederal regions most addicted to abstentionism".[14] The PSOE and Largo Caballero turned up their siren songs, Peirats records how "for the first time in many years Spanish Socialism publicly invoked the name of the CNT and brotherhood in the proletarian revolution" (idem). Reticence about any policy of alliance remained, however the position of agreement with the UGT was increasingly becoming the majority one within the CNT. It was seen as a means of avoiding the "principle of apoliticism". The UGT thus became the Trojan Horse for enrolling the CNT in an anti-fascist alliance with all the "democratic" fractions of capital. The CNT's and FAI's leaders were able to save face because they maintained the "principle" of refusing all pacts with the political parties. Anti-fascism did not enter by the front door of political agreements -so loudly rejected- but sneaked in through the back door of union unity.

The February 1936 elections

These elections, which are presented as being "decisive" in the struggle against fascism, ended up by eradicating all the resistance that remained in the CNT and FAI.

On the 9th January the secretary of the CNT's Catalunya regional Committee sent a circular to the unions calling a regional Conference in the Meridiana cinema, Barcelona, on the 25th "in order to discuss two concrete questions: 1st What should the CNT's position be on the question of the alliance with institutions that have a workerist complexion, without joining them" and 2nd What concrete and definitive attitude must the CNT adopt faced with the elections" (Peirats,op cit. page 106). Peirats says that, the majority of delegates , "saw the CNT's criteria of the anti-electoral position more as a question of tactics than as a principle" and that "The discussion revealed a state of ideological vacillation" (idem).

The positions favourable to abandoning the CNT's abstentionist tradition became increasingly stronger. Miguel Abós from the Zaragoza region declared in a meeting that "to fall into the torpor created by an abstentionist campaign would be the same as fermenting the Rights victory. And we all know the bitter experience of two years of persecution carried out by the Right. If the Right wins, I assure you that the furious repression unleashed in Asturias will be spread throughout Spain" (quoted in The Zaragoza Congress, a book previously cited about the Congress, page 171).

These interventions systematically distorted reality. The barbaric repression carried out by the capitalist left between 1931-33 was forgotten and only the Rights repression of 34 remembered. The repressive nature of the capitalist state whatever fraction was governing was carefully veiled over, avoiding the minimum of analysis, whilst the monopoly of repression was exclusively attributed to the fascist branch of capital. The CNT swept away by anti-fascism, which poses an analysis as irrational and aberrant as that of fascism, clearly decided to support the bourgeois state by voting for the Popular Front whose programme Solidaridad Obrera had denounced as a "a profoundly conservative document" that clashes with the "revolution spirit that oozes from the Spanish skin".[15] This crucial step was expressed in the Manifesto issued by the National Committee 2 days before the election where we can read:

"We, who do not defend the Republic, but who give no quarter in the struggle against fascism, will contribute all the forces that we dispose of to defeating the historical executioners of the Spanish proletariat (...). The uprising [of the military] is subordinated to the outcome of the elections. The theoretical and preventative plan will be able to be put into practice if the left wins the elections. Furthermore, without a doubt we can say that, faced with the armed insurrection of the legions of tyranny, there will be an unstinting agreement with the anti-fascist forces, energetically working for the defensive action of the masses to be directed towards a true social revolution, under the auspices of Libertarian Communism".[16]

The declaration had enormous repercussions since it was made at a very opportune moment, only two days before the election: it clearly influenced the vote of many workers. The CNT's complicity in the enormous electoral swindle perpetuated against the Spanish proletariat allowed the triumph of the Popular Front, and at the same time, meant its unconditional adherence to the anti-fascist movement.

The FAI clearly shared the CNT's attitude, Gómez Cases in his history of the FAI (page 179 English Edition) says that: "The position ‘On the Elections' also merits some comments. The F.A.I. reaffirmed its traditional anti-parliamentary and anti-electoral position in its relation at the F.A.I. national plenum. However, its campaign was very different from that of 1933 and there was practically no abstention from voting. Referring to the coincidence that C.N.T. and F.A.I. militants would take no risk with an anti-electoral strategy, Santillan himself told us that "the initiative for this change came from the F.A.I. Peninsular Committee, which was in a secure underground and could have for the riskiest offensive action".

If in 1931 the juggling act of the the syndicalist section of the CNT., aimed at securing participation in the elections met strong opposition (form other sectors and the FAI), now the whole CNT -supposedly freed from the syndicalist sector that had gone along with the Opposition unions- and the FAI without much fuss went much further in their support for the Popular Front. A new government that did all it could to delay the amnesty for more than 30000 political prisoners (many of them militants of the CNT[17]), continued the repression of striking workers with the same ferocity as the previous right-wing government and, stopped the re-employment of those workers who had been thrown out of work.[18] The government that the CNT had supported as supposedly leading the struggle against the advance of fascism retained all of the generals with ambitions to carry out a coup -amongst them the astute Franco - who later became the great dictator.

The CNT and FAI stabbed the proletariat in the back. We said in the last article of this series that the CNT had prepared to consummate its marriage with the bourgeois state at its 1931 Madrid Congress but that his had been delayed. They consummated it now! Proof of this, and one which the leaders of the CNT and FAI were very aware of- was given by Buenaventura Durruti on the 6th March -less than a month after the February electoral massacre concerning the new government's repression of the strikes by transport and water workers in Barcelona. In this Durruti -seen as one of the most radical militants of the CNT- launched the typically complicit reproaches often made by the syndicalists and opposition parties: "We say to the men of the Left that we were the ones who brought about your triumph and that we are the ones carrying out two conflicts that ought to be solved immediately". In order to leave no doubt he recalled the services rendered to the new government: "The CNT, the Anarchists, following the recent electoral victory, are in the street -the gentlemen of the Esquerra know it- in order to stop the functionaries who do not want to accept the popular will. Whilst they occupy the ministries and positions of command, the CNT has to be in the street in order to stop the victory of a regime that we all repudiate".[19]

These comments were quoted by the Puerto de Sagunto delegation which was one of the few at the Zaragoza Congress to dare to show any critical reflection "After listening to these words, How can anyone still doubt the torturous, preposterous and calloborationist conduct of, if not all, a large part of the Confederal Organisation? Durruti's words appear to show that the Cataluyna Organsation in a matter of days has been turned into the honorary guard of the Catalan Esquerra".

The Zaragoza Congress: the triumph of syndicalism

Held in May 1936 this congress has been presented as the triumph of the most extreme revolutionary positions because of the adoption of the famous Resolution on libertarian communism.

We will analyse this resolution more fully in another article but here we are going to look at the development of the congress, analysing the atmosphere that dominated it and considering the resolutions and results. From this point of view, the congress marked the unarguable victory of syndicalism and the sealing of the CNT's integration into bourgeois politics through anti-fascism (which we have dealt with above). The proletarian tendencies and positions that tried to express themselves were decisively silenced and weakened by phraseology about unity around the "social revolution" and the "implanting of libertarian communism", syndicalism, anti-fascism and unity with the UGT.

One of the few delegations that expressed the minimum of lucidity at the congress was that from Puerto de Sagunto, which we have already quoted, who warned - with hardly any backing from other delegations- that "The organisation, between October to now, has radically changed, the anarchist sap that runs through its arteries, if it has not totally disappeared has been greatly reduced. If there is not a healthy reaction, the CNT will take giant steps towards the most castrated and annoying reformism. Today the CNT is not the same as that of 1932 and 1933, neither in revolutionary essence or vitality. The morbid agents of this policy have made their mark on the organisation. It has been obsessed about gaining increasing numbers of members without stopping to examine the problems that many of these individuals have caused. Ideological development has been completely forgotten and all that matters is numerical growth, despite the first being more essential the second".[20]

The CNT of Zaragoza had nothing to do with that of 1932-33 (which had already been weakened as a proletarian organisation, as we demonstrated in a previous article in this series) but, above all, it had nothing in common with the CNT of 1910-23 when it was a living organism, dedicated to the everyday struggles and reflection of the working class, along with the struggle for an authentic proletarian revolution. Now it was simply a union totally polarised by anti-fascism.

At the Congress the delegation of the CNT's railway union could tranquilly say without meeting the least opposition that "as railway workers we will solve our problems just as other workers have done, through asking for improvements, but we should never take this for the beginning of a revolutionary movement" (Minutes page 152).

This declaration was made in relation to the balance sheet of the insurrectional movements of December 1933 (which had been deprived of the strengthening that a railway strike could have given it because the union called it off at the last moment), demonstrates that syndicalism: imprisons each section of workers in "their problem" trapping them in the structures of capitalist production and thus undermining class solidarity and unity. The union slogan " that each sector deals with its own problems first" represents the "workerist" way of entangling workers in solidarity with capital and thus breaking all class solidarity as a class.

The Gijón delegation flagrantly denied the most elemental solidarity with the exiled CNT victims of the repression of the 1934 Asturias insurrection (see page 132 of the minutes, op cit). The National Committee made no comment upon this serious lack of solidarity, something that would have been unthinkable only a few years before. Clearly embarrassed by this the Fabril de Barcelona delegation tried to silence this question through a diplomatic proposition:

"We have sufficiently strong reasons for closing this debate in a completely satifactory way. The Asturian region has drawn a line under this incident since the ex-exiles are present at this congress as delegates. Moreover if there is a letter of the National Committee where support and aid are not advised there is another later one that goes back on this position.[21] The delegates who pose this problem want us to recognise them as comrades and to give them our entire confidence. The congress satisfies this request and the question is resolved."

This abandoning of the most elemental workers' solidarity expressed such a really incredible attitude that the Segunto delegation denounced it : "We protest about the paragraph refering to the management of the National Committee about the government and we say that the Vagos and Maleantes law[22] should not be applied to the Confederación Nacional del Trabajo. However what we have to ask for is the abrogation of this law. It is not right to think that something that is bad for us is good enough for others" (Minutes page 106).

At the congress one could hear an intervention praising, advising, recommending that "in relation to strikes there has not been the necessary prudence that would have saved energies in order to channel them towards other struggles. This defect could be corrected by directing the workers to make demands of the bourgeoisie that have gone through the Sections and the Industrial Relations Committees in order to allow the situation to be studied and thus avoiding the disorderly calling of strikes" (Minutes, page 196, Hospitalet delegation). That is to say, the demand that had been the spearhead of the syndicalists struggle in 1919-23: the regulation of strikes through the "peer organs". This is the same idea of the mixed panels with which the Republican/Socialist government of 1931-33 had tried to straight jacket strikes and the CNT itself.

These were the typical expressions of the union mentality which tries to control and dominate workers' struggles through sabotaging them from within. When workers seek to defend their demands, the unions talk pessimistically about "unfavourable conditions" and craftily insists upon "not wasting energies". However, when the unions call for struggles this is done in order to dampen down workers combativity or to lead them to bitter defeat, and accompanied by exaggerated optimism about the possibility of success and reproach workers for their "meanness" if they do not join in.

One of the most of the most flagrant expressions of this trade union mentality was the resolution adopted by the congress on unemployment. It made more or less correct points about the causes of unemployment and correctly insisted that "the proletariats suffering will only be ended by the social revolution" (page 217). However, this remained a hollow phrase negated by the "minimum programme" that proposed "36 hour week", "the abolition of piece-work", "obligatory retirement at 60 for men and 40 for women of 70% of wages" (idem). Leaving to one side the stinginess of these proposals the problem is the thinking behind the minimum programme, is based on the illusion that there can be a dynamic towards regulated improvements within capitalism. Syndicalism could not escape from this illusion since this was the essence of its activity: to work within the relations of capitalist production in order to improve workers' conditions, something that was possible in the ascendant period of capitalism but impossible in its decadent epoch.

There was an even worse resolution however and one which did not give rise to any criticism at the Congress. In its preamble it tranquilly affirmed that:

"England has tried unemployment benefits but this was an absolute failure, since parallel with the poverty of the obliging masses with outrageous subsides, it lead to the economic ruin of the country since it had to parasitically maintain millions without work on sums which, though not fabulous, represented a significantly importance investment of the country's economic reserves on philanthropic works".[23]

The same congress that dedicated part of its work to defining the "social revolution" and "libertarian communism" also took up a preoccupation for safeguarding the national economy, which classified as parasitic the payment of unemployment benefits and lamented the waste of the nation's resources on " philanthropic works"!

How could an organisation that called itself "worker" call unemployment benefits "parasitic"? Could it not understand the basic ABC that unemployment benefits had already been paid for by many hours of work by them or their brothers and sisters still in work and in no way represents philanthropy? These laments have more to do with the politics of the Right and the bosses than unionists or the politics of the Left who distinguish themselves precisely from the Right by being more guarded and not usually saying what they think or expressing it in a deceitful way.

However this does not mean we are at all surprised that a union which was rhetorically preparing to "carry out the social revolution" adopts such things. Unions have no other playing field than the national economy and its aim -even more than that of its associate adversaries, the bosses- is the defence of the whole of its interests. Trade unionism only proposes to gain improvements within the relations of capitalist production. In the historic period of capitalism's expansion this allowed it to be a weapon of the class struggle. In the global context of strong contradictions workers conditions could be improved and the prosperity of the economy could develop in parallel. However, in the period of decadence this is no long possible: in a society marked by permanent crisis, moves towards war and war itself, the salvation of the national economy demands as its unavoidable condition the sacrifice of workers and a more or less permanent increase in their exploitation.

In 1931, the split of the unionist tendency organised in the Opposition Unions, lead the anarchists to believe that the danger of syndicalism had disappeared. They appeared to think: kill the dog put an end to rabies. But reality was very different: the blood that coursed through the CNT's veins was syndicalist and the syndicalist mentality far from being weakened was increasing reinforced. The activism of the 1932-33 insurrectional period was as dangerous mirage. From 1934 the reality was that: syndicalism and anti-fascism -mutually reinforcing each other- were inexorably imposed definitively trapping the CNT -and with it the FAI- in the cogs of the bourgeois state. The delegation of Various Officies of Igualada bitterly recognised this: "many of those who see themselves as staunch defenders of the CNT's positions have unconsciously and inadvertently turned us into mere sponsors of an increasingly bourgeois republican government" (Minutes page 71).

The Zaragoza congress dedicated a good part of its sessions to re-uniting with the opposition unions. Despite the exchange of numerous mutual recriminations which were accompanied by the rhetorical change of "welcomes" and "hand shakes" the terrain that lead to this re-unification was that of syndicalism and anti-fascism. The Anarchists sector - in order to deceive themselves and others - highlighted the proclamations about the "social revolution" and adopted with hardly any discussion the famous resolution on libertarian communism . This repeated the same manoeuvre that they had criticised the Syndicalists for in 1919 and afterwards in 1931: wrapping up syndicalist politics and collaboration with capital in the attractive wrapping paper of the "rejection of politics" and "revolution".

The two parts were re-united on the terrain of capitalism. Therefore the delegate of the Valencia Opposition could challenge the report on reunification without meetings hardly any objections..

In way of conclusion

The spectacular events that took place from July 1936 in which the CNT was the main protagonist: demobilising and sabotaging the workers' struggles in Barcelona and other parts of Spain in response to the Fascist uprising, its unconditional support for the Catalan Generalitat and participation, at first indirectly and then openly in this government; the sending of ministers to the Republican government are well known.[24]

These facts clearly show the CNT's treason. But they are not a storm that suddenly appeared from a blue sky. Throughout this series we have tried to show why this terrible and tragic situation of the loss for the proletariat of an organisation born from its own efforts took place. It is not a question of destroying a great myth or revealing a grand lie but of examining with a global and historical method the processes that led to this betrayal. The series on revolutionary syndicalism and within that the series of articles on the CNT,[25] has tried to provide the materials for opening up a discussion that will allow us to draw lessons to arm ourselves with faced with the struggles to come. Confronted with the tragedy of the CNT we can -as the philosopher said- neither laugh or cry but only understand.

RR and C. Mir 12.3.08

[1] See the 5th article of this series in International Review n°132: "Anarchism fails to prevent the CNT's integration into the bourgeois state (1931-32) [1]".

[2] See the 4th article of this series in International Review n°131: "The CNT's contribution to the constitution of the Spanish Republic (1921-31) [2]".

[3] We have published different texts that can be consulted, some of these were written by the few revolutionary groups which resisted the "anti-fascist" tide during that period.

[4] It is necessary to underline that workers unity cannot be achieve through the agreement of political and union organisations. The experience of the 1905 Russian Revolution showed that workers unity is achieved in a direct way, through massive struggle and has its organisational source in the general assembles and when the revolutionary situation unfolds through the formation of workers' councils.

[5] From Olaya's Historia del movimiento obrero español (1900-1936), Vol 2 page 877. The references for these books are found in the second article on the CNT.

[6] A split that last from 1931 to 1936 lead by openly syndicalist elements in the CNT. See the fifth article in our series.

[7] This pact was hidden from the National Committee before it was put in place.

[8] Held in May 1936. See more above.

[9] The second newspaper besides the legendary Solidaridad Obrera.

[10] Page 163 of The Zaragoza Conferderal Congress, ZYX Edition, 1978.

[11] For many years he was the main leader of both the PSOE and the UGT.

[12] He had been Minister of Labour in the 1931-33 Republian-Socialist government, responsible for innumerable workers deaths and before that had been a state advisor to the dictator Primo de Rivera.

[13] Olaya op cit page 887.

[14] From The CNT in the Spanish revolution, vol 1 page 106. See bibliographical references in the first part of this series

[15] The articles appeared on the 17-1-1936 and 2-4-1936.

[16] Cited by Peirats op cit page 113.

[17] We should remember that this amnesty for the syndicalist prisoners was one of the most repeated motives given by the CNT and the FAI for its vigorous support for the Popular Front.

[18] We would add to this that the Agrarian Reform , a timed and stingy law , was not what was promised and between February and July the "Popular" government practically maintained a state of emergency and brutal press censorship which effected the CNT above all.

[19] Cited in the minutes of the Zaragoza Congress of the CNT, page 171.

[20] Minutes of the Zaragoza Congress, op cit, page 117.

[21] This according to the minutes of the congress caused uncertainty and confusion. During the debate, the National Committee affirmed "all we said was that we could not advise class solidarity".

[22] This odious and repugnant law which gave the government enormous repressive powers was adopted by the "very democratic" "workers'" Spanish Republic.

[23] Minutes page 215, op cit.

[24] We have analysed this in our book: Franco y La República masacran a los trabajadores.

[25] The first began with International Review n°118 whilst the second commenced in n°128.

Historic events:

- Asturias [3]

- Zaragoza Congress [4]

Geographical:

- Spain [5]

Deepen:

History of the workers' movement:

- 1936 - Spain [7]

Political currents and reference:

People:

- Largo Caballero [9]

Editorial: The United States - locomotive of the world economy... toward the abyss

- 3684 reads

Times are hard for the world economy! Not only has it still to get over last year’s sub-prime crisis in the US housing market, the overall situation of the capitalist economy has never seemed so dangerous since the late 1960s: despite all the efforts of the ruling class to fend it off, the crisis is back with a vengeance. The US housing crisis has been transformed into an international financial crisis, with alarms going off everywhere as American and European banking and financial institutions appear to be threatened with insolvency.[1] Those financial institutions that were in danger of bankruptcy have only survived thanks to state intervention, and there is a real fear that many financial institutions which up to now had been considered safe, may find themselves in danger of bankruptcy and so creating the conditions for a major financial crash. The crisis of confidence gripping the international banking system has aroused serious concern among many fractions of the world ruling class that there is a real danger of the whole system seizing up, making it impossible for companies and households to get the credits (even at higher prices) on which the economy’s activity depends. There is a risk that a full-blown financial crash be combined with a whole series of other “economic disasters” which are by no means accidents, but which on the contrary are expressions of a violent return of an economic crisis which the bourgeoisie has been trying to stave off by every means possible:

A forecast slowdown in economic activity, or even a recession in the case of some countries, such as the United States. The bourgeoisie managed to overcome successive crises since the 1970s thanks to an ever-growing mountain of debt, which brought ever more meager results. Will it be possible to hold off recession once again without new and greater injections of debt, with all the risks that implies for the stability of the world’s banking and credit mechanisms.

The decline in share values, punctuated by the occasional abrupt fall, has shaken confidence in the foundations of the whole system of speculation. The successes of stock exchange speculation, which made it possible to hide much of the difficulties of the world economy in particular by contributing in large part to the rise in company profitability since the mid-1980s, also created the myth that equity values could only go on rising no matter what ups and downs affected the economy.

The weight of military spending is an increasingly intolerable burden on the economy, as we can see clearly in the case of the USA. And yet this weight cannot be reduced at will. It is the consequence of the growing weight of militarism in social life, where each nation is increasingly pushed into military adventures at the same time as it is confronted with ever more insurmountable economic difficulties.

The return of inflation doubly haunts the bourgeoisie. On the one hand it threatens to reduce trade as a result of more and more unpredictable fluctuations in prices. At the same time, it is easier for workers to spread the struggle to other branches of industry when the fight concerns the defense of wages eaten away by inflation than when it concerns the threat of redundancy for example. Yet the only means for holding back inflation – reduction in credit and state spending – would only make the recession worse if they were put into operation.

Consequently, the present situation is not just a worse remake of all the crises since the 1960s, it concentrates them all in one explosive bundle which has given the economic disaster a whole new quality, much more likely to lead to a calling into question of the whole system. Another sign of the times is that whereas up to now it is America that has played the part of locomotive to draw the world economy out of recession, the only direction that the USA seems likely to draw the world today, is over the cliff and into recession.

The deepening economic crisis in the United States

When it comes to the economic situation in the U.S., George Bush is the most optimistic man in America—he may be the only optimist in America.[2] February 28th, even though he acknowledged the risk of an economic slowdown, the President declared, “I don’t think we’re headed for a recession… I believe that our economy has got the fundamentals in place for us… to grow and continue growing, more robustly that we’re growing now. So we’re still for a strong dollar.” Two weeks later, on March 14th, the President reaffirmed his optimistic outlook before a meeting of economists in New York City where he expressed confidence in the “resilient” American economy. He did this on the very day that the Federal Reserve and JP Morgan Chase were forced to collaborate on an emergency bailout plan for Bear Stearns, the Wall Street investment bank, after it suffered a run on the bank reminiscent of the Great Depression; that crude oil prices hit a record high $111 per gallon, despite the fact that supply far exceeds demand; that the government announced that mortgage foreclosures rose 60 percent in February; and that the dollar hit a record low against the Euro. Bush’s denial of reality notwithstanding, it is clear that the appearance of prosperity that accompanied the housing boom and real estate economic bubble of the last few years has given way to a full-blown economic catastrophe in the world’s most powerful economy, thus putting the economic crisis in the forefront of the international situation.

The housing crisis is symptomatic of a chronic crisis of the system.

Ever since the first signs that the housing boom was coming to an end at the beginning of 2007, bourgeois economists began debating the odds of a recession in the US economy. Just three months ago, at the beginning of 2008, the predictions ranged considerably, stretching from the ‘pessimists’ who thought that a recession had already started in December, to the ‘optimists’ who were still expecting a miracle that would avoid it. In the middle, hedging their bets, were the uncommitted experts saying that the economy “could literally go either way.”

Things have gone so bad so fast in the last two months that, except for Bush, there is no more room for optimism or ‘centrism.’ The consensus is now that the good times have come to an end. In other words the American economy is now in recession or, at best, in the edge of one.

However this bourgeois recognition of American capitalism’s troubles has little value for understanding the real state of the system. The bourgeoisie’s official definition of an economic recession is two consecutive quarters of negative economic growth. The National Bureau of Economic Research uses different, slightly more useful criteria, defining recession as a significant, protracted decline in activity that cuts across the economy, affecting measures like income, employment, retail sales and industrial production. On the basis of these definitions, the bourgeoisie can’t identify a recession until it has been underway for a while, often until the worst of it is already past. Thus according to some estimates one will have to wait until late this year to know if there is a recession, or, the date of its beginning.

In this sense the recession predictions that fill the pages of economic sections of newspapers and magazines are very misleading. In the last instance they only contribute to hiding the catastrophic state of American capitalism that can only get worse in the months to come regardless of when the economy officially enters in recession.

What is important to emphasize is that the present slump is far from reflecting a supposedly “healthy” American economy that is simply going through a troubled phase in an otherwise normal business cycle of expansion and bust. What we are witnessing are the convulsions of a system in a chronic state of crisis that can only buy ephemeral moments of “health” by toxic remedies that only aggravate the next catastrophic collapse.

This has been the history of American capitalism - and global capitalism- since the end of the sixties with the return of the open economic crisis. For the last four decades through official expansions and busts, the overall economy has only kept a semblance of functionality thanks to systematic state capitalist monetary and fiscal policies that the government is obliged to apply to fight the affects of the crisis. However the situation has not remained static. During these decades of crisis and state intervention to manage it, the economy has accumulated so many contradictions that today there is a real threat of an economic catastrophe, the likes of which we have not seen in the history of capitalism.

The bourgeoisie bought its way out of the burst of the technology/internet bubble in 2000/01 by creating a new bubble based, this time, on real estate. Despite the fact that companies in key industries in the manufacturing sector– the auto and air line industries for instance— continue going bankrupt, the real estate boom for the last five years gave the semblance of an expanding economy. Now the boom has transformed itself into the present bust that has shaken the whole edifice of the capitalist system and which will still have future repercussions that no one can yet predict.

According to the latest data about the real estate crisis, activity related to private housing is in total disarray. New home construction has already fallen by around 40 percent since its peak in 2006; sales have fallen even faster, dragging prices down with it. Home prices have dropped by 13 percent nation-wide since the peak in 2006 with predictions that they will fall by another 15 to 20 percent before hitting bottom. The real estate boom has left a huge inventory of vacant unsold homes— about 2.1 million, or about 2.6 percent of the nation’s housing supply. And the glut is bound to increase as the wave of foreclosures continues to broaden, hitting even borrowers with supposedly good credit. Last year’s foreclosures were mostly limited to the so-called sub-prime mortgages—loans given to people with essentially no means to repay. Nearly one-fourth of such loans were in default by last November. Although default rates on loans given to people with relatively good credit are much lower, they are also rising. In November, 6.6 percent of these loans were either delinquent, in foreclosure, or had been repossessed. In a sign of worse things to come, this spike in foreclosures is happening even before many mortgages have reset to higher interest rates. The declining real estate values that have accompanied the crisis means that many people hold mortgages that exceed the current value of their homes, which means that they couldn’t even recoup their losses if they sold their homes. This creates a situation in which in is more financially sensible to walk away from their mortgage obligations and declare bankruptcy.

The bursting of the real estate bubble is wreaking havoc in the financial sector. So far the crisis in real estate has generated over 170 billion dollars in losses at the world’s largest financial institutions. Billions of dollars in stock market value have been wiped out, rocking Wall Street. Among the big names that lost at least a third of their value in 2007 were Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac, Bear Stearns, Moody’s, and Citigroup.[3] MBIA, a company that specializes in guaranteeing the financial health of others, lost nearly three-quarters of its value! Several of yesterday’s high-flying mortgage related companies have gone bankrupt.

And this is only the beginning. As foreclosures accelerate in the coming months banks will be counting new losses and the credit crunch already in place will tighten up even more, impacting further other sectors of the economy.

From the housing crisis to the credit crunch

Moreover, the financial crisis related to the mortgages is only the tip of the iceberg. The same reckless lending practices that were dominant in the mortgage market were also the norm in the credit card and auto loan industries, where problems are also increasing. And here lies the essence of today capitalist “health”. Its little dirty secret is the perversion of the mechanism of credit as a way to buy its way out of a lack of solvent markets to sell its commodities. Lending is no longer a promise of repayment with a profit backed up by some material reality (i.e., collateral) that can stimulate capitalist development. It has essentially become a way of keeping the economy artificially afloat and preventing the collapse of the system under the weight of its historic crisis. Already in the 1980’s the financial crisis that followed the bust of the Latin American economies that were weighed down by huge debts that they had no means to repay had demonstrated the limits of credit as a remedy to deal with the crisis. The same lesson could have been learned in 1997 and 1998 at the time of the collapse of the Asian tigers and dragons, and Russia’s default on its debt. In fact the housing bubble itself was a reaction to and an effort at overcoming the burst tech/internet bubble. One can justly pose the question, what is the next bubble going to be?

Yet there is another aspect of the present financial crisis. This is the rampant speculation that accompanied the real estate bubble. What we are talking about is not small time speculation by an individual investor buying a house and quickly flipping it to make a quick buck from the fast appreciation of the value of the property. This is peanuts. What really counts is the big time speculation that all the major financial institutions engaged in through the securitization and selling of mortgage-debt on the stock market. The exact mechanisms of these schemes are not completely but from what is known they look very much like the age old ponzi schemes. In any case, what this monstrous level of speculation shows is the degree to which the economy has become a “casino economy” where capital is not invested in the real economy, but instead it is used to gamble.

The crisis reveals the bluff of liberalism and the crisis of state capitalism

The American bourgeoisie likes to present itself as the ideological champion of free market capitalism. This is nothing but ideological posturing. An economy left to function according to the laws of the market has no place in today’s capitalism, dominated by omnipresent state intervention. This is the sense of the “debate” within the bourgeoisie on how to manage the present economic mess. In essence there is nothing new being put forward. The same old monetary and fiscal policies are applied in hope to stimulate the economy.

For the moment what is being done to alleviate the current crisis is more of the same— the application of the same old policies of easy money and cheap credit to prop up the economy. The American bourgeoisie’s response to the credit crunch is yet more credit! The Federal Reserve has cut its interest rate benchmark 5 times since September and seems posed to do so once more at its next scheduled meeting in March. In a clear recognition that this medicine is not working the Fed has steadily increased its intervention in the financial markets offering cheap money – $200 billion in March, on top of another multibillion package offered last December— to the financial institutions that are short on cash.

For their part the White House and Congress moved quickly as well in passing a so-called ‘economic stimulus package”, in essence approving rebates for families and tax breaks for businesses and passing legislation geared towards easing the mortgage defaults epidemic and reviving the battered housing market. However given the extent of the housing and financial crisis there is even growing consideration of proposals for a massive bailout by the State of the whole housing debacle, the price tag of which would make the huge $124.6 billions bailout by the State of the Saving and Loans industry in 1990 look insignificant.

What these efforts by the State to manage the crisis will amount to remains to be seen. What is evident is that more than ever the bourgeoisie has less margin of maneuver for its economic policies. After decades of managing the crisis, the American bourgeoisie presides over a very sick economy. The monstrous public and private national debt, the federal budget deficit, the fragile financial system, and the huge trade deficit, all these make more difficult for the bourgeoisie to deal with the collapse of its system. In fact so far the traditional government medicine to jolt the economy has failed to produce any positive results. On the contrary it seems to be aggravating the illness that it is intended to cure. Despite the Fed’s moves to easy the credit crunch, stabilize the financial sector and revive the mortgage market, credit is in short supply and expensive, the Wall Street rollercoaster ride continues unabated with wild swings and an overall downward tendency, and rising mortgages rates are not helping to alleviate the housing slump. Furthermore the Fed’s policy of cheap money is contributing to the downward plunge of the dollar, which every week is hitting new lows against the Euro and other currencies and driving up prices of key commodities like oil. This rising price of energy, food and other commodities at the same time of a sharply slowed down economic activity are fueling fears among the “experts” about the prospect of a period of “stagflation” for the American economy. Today rising inflation is already squeezing consumption of people trying to survive on fixed incomes and obliging the working class and other sectors of the population to tighten their belts.

Attacks on the US working class

The March 7 announcement by the U.S. Labor Department that 63 000 jobs were lost nationwide during the month of February sent jitters around the bourgeois world. Surely not because of concerns for the lot of laid-off workers but because this sharp decline in employment confirmed the economists’ worst nightmares of a worsening crisis. It was the second consecutive decline in employment and the third straight drop for the private sector. However in a kind of sick joke at the expense of unemployed workers, the overall unemployment rate declined from 4.9 to 4.8 percent. How is this possible? The reason is nothing but a clever statistical trick used by the bourgeoisie to underreport the number of unemployed. For the U.S. government, you are only unemployed if you are out of job, have actively looked for one in the last month and are ready to work at the moment of the survey. Thus the official unemployment rate significantly understates the jobs crisis. It ignores millions of “discouraged” American workers who have lost their jobs and have given up on the possibility of finding a new one and haven’t applied for a new job in the previous 30 days at the time of the survey, or who want to join the workforce but are too discouraged to try because the job situation remains so bleak or simply are not willing to work for half the wage rate that they had in their recent lost job, or millions of underemployed workers who want to work fulltime but are forced to work part-time because there are no fulltime jobs available. If these workers were included the unemployment statistics, the rate would be significantly higher. To further underreport unemployment, since 1983, thanks to Ronald Reagan’s statistical sleight of hand, U.S.-based military personnel have bee considered part of the domestic workforce (previously unemployment was calculated based on the civilian workforce only). This maneuver adds nearly two million man and women “employed” by the U.S. military to the denominator used to calculate the unemployment rate, artificially lowering the rate.

The present economic slump is bringing an avalanche of lay-offs across all sectors of the economy, but one has to say that the now defunct housing boom was not a paradise for the working class. Income, pensions, health care, working conditions, all continued to deteriorate while the housing market was booming. This fact has led even some bourgeois economists to point out that this was a ‘jobless’ and ‘wageless’ recovery. But even this recognition falls short of presenting the whole picture. The reality is that for the working class, working and living conditions have continued to deteriorate for the last four decades of open economic crisis, expansions and busts not withstanding. As this crisis worsens during the present economic slump there is nothing in store for the working class but more misery as the bourgeoisie tries to make it bear the impact of its economic difficulties.

The dire conditions facing the American economy portends a bleak economic picture on the global level. The world’s biggest, most powerful economy will surely bring its trading partners down with it. There is no economic engine that can compensate for the American plunge and keep the global economy afloat. The credit crunch will undermine world trade, the collapse of the dollar will slash exports to the U.S. aggravating the economic situation in country after country, and the attacks on the proletariat’s standard of living will increase everywhere. If there is one bright spot, it is that all of this will accelerate the return of the proletariat to reclaiming the class struggle against capitalism, as it is forced to defend itself against the ravages of the capitalist crisis.

The perspective of the acceleration of the capitalist crisis brings with it the promise of a development of the class struggle: in it, the proletariat will have to go beyond the steps forward it has already made since the historic recovery of the struggle at the end of the 1960s.

ES/JG March 14, 2008

[1] See the article in International Review n°131: “From the crisis of liquidity to the liquidation of capitalism”

[2] Misplaced optimism seems to be a characteristic of American presidents. Thus Richard Nixon declared in his 1969 inaugural address, just two years before the crisis which would force the US to abandon dollar convertibility and the whole Bretton Woods system: “We have learned at last to manage a modern economy to assure its continued growth”. On 4th December 1928, just months before the crash of 1929, his predecessor Calvin Coolidge spoke to the US Congress in these terms: “No Congress of the United States ever assembled, on surveying the state of the Union, has met with a more pleasing prospect than that which appears at the present time (…) [The country] can regard the present with satisfaction and anticipate the future with optimism”.

[3] This article was written just before the announce that Bear Stearns – the USA’s fifth largest merchant bank - would be sold to JP Morgan as part of a government sponsored rescue operation, for $2 per share, i.e. a reduction in value of 98%.

Geographical:

- United States [10]

Recent and ongoing:

- Economic Crisis [11]

Internal debate: the causes of the post-1945 economic boom

- 5326 reads

In spring 2005, the ICC launched an internal debate focused on the underlying causes of the economic boom that followed World War II;[1] this period remains an outstanding exception within the history of capitalism's decadence, achieving spectacular and then historically unprecedented overall growth rates for the world economy.[2]

Elements of this debate had already been posed within our organisation, in particular concerning the economic role played by the two world wars and by the war economy in general, centred essentially on the key question of whether the destruction caused by war was in some way responsible for the post-war booms after 1918 and 1945. Indeed, this had led to the appearance of certain contradictions between various ICC texts on the question. As the debate got under way, it quickly became clear that if - as some argued - the destruction caused by war could not be said to open new markets (since the reconstruction that followed the wars took place entirely within the sphere of the existing capitalist economy), then this in turn opened a much broader problem: what other coherent explanation could account for the post-war boom that followed 1945? Although the debate is still ongoing, and the different positions continue to represent, up to a point, "work in progress", we consider nonetheless that their outlines are sufficiently clear for us to present them to comrades outside the organisation with a view to encouraging debate among all those interested in the positions of the Communist Left.

One might imagine that events prior to and since the post-war boom had sufficiently demonstrated its exceptional nature, for a debate on the subject to be of purely academic interest. We consider it critical nonetheless, since these questions go to the core of the marxist understanding of the historically limited character of the capitalist mode of production, the system's entry into decadence and the insoluble nature of the present crisis. In other words, they concern one of the main objective foundations of the proletariat's revolutionary perspective.

The context of the debate: certain contradictions in our analyses

The debate on the economic implications of war in capitalism's decadence is not new to the ICC, and had indeed already been posed in the workers' movement, notably by the Communist Left. Our pamphlet on The Decadence of Capitalism[3] explicitly developed the idea that the destruction provoked by the wars in the phase of decadence, and in particular the world wars, could constitute an outlet for capitalist production, by creating a market based on post-war reconstruction:

"...the external outlets have contracted rapidly. Because of this, capitalism has had to resort to the palliatives of destruction and arms production to try to compensate for rapid losses in ‘living space'." (Section 5: "The turning-point of the 1914-18 war")

"Through massive destruction with an eye to reconstruction, capitalism has discovered a way out, dangerous and temporary but effective, for its new problems of finding outlets.

During the first war, the amount of destruction was not ‘sufficient' (...) In 1929, world capitalism again ran into a crisis situation. As if the lesson had been well-learned the amount of destruction accomplished in World War II was far more intense and extensive (...) a war which for the first time had the conscious aim of systematically destroying the existing industrial potential. The ‘prosperity' of Europe and Japan after the war seemed already foreseen by the end of the war, (Marshall Plan, etc...)" (Section 6: "The cycle of war-reconstruction").

A similar idea is present in other texts of the organisation (notably in the International Review) as well as among our predecessors in the Italian Left: in an article published in 1934 by Bilan we read, for example, that "The slaughter that followed formed an enormous outlet for capitalist production, opening up a ‘magnificent' perspective (...) While war is the great outlet for capitalist production, in ‘peacetime' it is militarism (i.e. all the activities involved in the preparation for war that realises the surplus value of the fundamental areas of production controlled by finance capital" (Bilan n°11, 1934, ‘Crises and cycles in the economy of capitalism in agony' republished in International Review n°103).

Other ICC texts, written both before and after The Decadence of Capitalism was published, developed a very different analysis of the role of war in the period of decadence, harking back to the report on the international situation at the July 1945 conference of the Gauche Communiste de France, for whom war "was an indispensable means for capitalism, opening up the possibilities of ulterior development, in the epoch when these possibilities existed and could only be opened up through violent methods. In the same way, the downfall of the capitalist world, which has historically exhausted all the possibilities for development, finds in modern war, imperialist war, the expression of this downfall which, without opening up any possibility for an ulterior development, can only hurl the productive forces into an abyss and pile ruins upon ruins at an ever-increasing pace".

The report on the course of history adopted at the ICC's 3rd Congress[4] refers explicitly to this passage from the GCF's text, as does the article ‘War, militarism and imperialist blocs in the decadence of capitalism', published in 1988,[5] which emphasises that "what characterises all these wars, like the two world wars, is that unlike those of the previous century, at no time have they permitted any progress in the development of the productive forces, having had no other result than massive destructions which have bled dry the countries in which they have taken place (not to mention the horrible massacres they have provoked)".

The framework of the debate

These questions are important because they give a theoretical foundation and coherence to the general political framework of a revolutionary organisation. They are nonetheless different from those class lines which separate the proletariat from the bourgeoisie and its hangers-on (internationalism, anti-working class nature of the trade unions, impossibility of taking part in parliamentary elections, etc.). The different analyses that have evolved during the debate are thus all entirely compatible with principles contained in the ICC's own platform.[6]

The critique of certain ideas contained in The Decadence of Capitalism has moreover been undertaken with the same method and general analytical framework that the ICC has used both when the pamphlet was written and since:[7]

- The ICC stands by the Communist International's recognition that World War I had opened a new "epoch of wars and revolutions", based on the fact that capitalism could no longer escape from the insurmountable contradictions assailing its system. The workers' movement had to understand the expressions and political consequences of this change in period.

- When we analyse the dynamic of the capitalist mode of production over a whole period, we must begin by studying, not the different sectors of capitalism (nations, enterprises, etc), but the world capitalist entity taken as a whole; it is the latter which provides the key to understanding each one of its parts. This was the method Marx used in studying the reproduction of capital, when he made it clear that "To rid the general analysis of purely incidental elements, it is necessary to treat the commercial world as a single nation" (Capital Volume One).

- "Contrary to what the idolaters of capital claim, capitalist production does not create automatically and at will the markets necessary for its growth. Capitalism developed in a non-capitalist world, and it was in this world that it found the outlets for its development. But by generalising its relations of production across the whole planet and by unifying the world market, capitalism reached a point where the outlets which allowed it to grow so powerfully in the nineteenth century became saturated. Moreover, the growing difficulty encountered by capital in finding a market for the realisation of surplus value accentuates the fall in the rate of profit, which results from the constant widening of the ratio between the value of the means of production and the value of the labour power which sets them in motion. From being a mere tendency, the fall in the rate of profit has become more and more concrete; this has become an added fetter on the process of capitalist accumulation and thus on the operation of the entire system" (ICC Platform).

- It fell to Rosa Luxemburg, on the basis of a critical appraisal of Marx's work, to develop the thesis that the enrichment of capitalism as a whole depended on the exchange of commodities with pre-capitalist economies ("foreign markets"), i.e. economies that practiced commodity exchange but had not yet adopted the capitalist mode of production: "In real life the actual conditions for the accumulation of the aggregate capital are quite different from those prevailing for individual capitals and for simple reproduction. The problem amounts to this: If an increasing part of the surplus value is not consumed by the capitalists but employed in the expansion of production, what, then, are the forms of social reproduction? What is left of the social product after deductions for the replacement of the constant capital cannot, ex hypothesi, be absorbed by the consumption of the workers and capitalists-this being the main aspect of the problem-nor can the workers and capitalists themselves realise the aggregate product. They can always only realise the variable capital, that part of the constant capital which will be used up, and the part of the surplus value which will be consumed, but in this way they merely ensure that production can be renewed on its previous scale. The workers and capitalists themselves cannot possibly realise that part of the surplus value-which is to be capitalised. Therefore, the realisation of the surplus value for the purposes of accumulation is an impossible task for a society which consists solely of workers and capitalists".Rosa Luxemburg, The Accumulation of Capital, ‘The Reproduction of Capital and its Social Setting'). The ICC has essentially adopted this position, which does not mean that there cannot exist within our organisation other positions which criticise Luxemburg's economic analysis, as we will see in particular with one of the positions in the present debate. Her analyses met with opposition in her own day, not only from the reformist currents which considered that capitalism was not doomed to provoke growing catastrophes, but also from revolutionary currents, in particular Lenin and Pannekoek, who considered that capitalism was a historically obsolete mode of production although their explanations were different from Luxemburg's.

- The phenomenon of imperialism derived precisely from the need for the developed countries to have access to pre-capitalist markets: "imperialism is the political expression of the accumulation of capital in its competitive struggle for what remains still open of the non-capitalist environment". (Accumulation of Capital: ‘Protective Tariffs and Accumulation')

- The historically limited nature of these extra-capitalist outlets constitutes the economic basis of the decadence of capitalism. The First World War was the expression of such a contradiction. Once the world had been divided up between the great powers, those who were left the worst off in terms of colonial possessions had no choice but to try to re-divide the world by military force. Capitalism's entry into its period of decline signified that the contradictions which beset the system were now insurmountable.

- State capitalism is the way the bourgeoisie, in the period of decadence, uses various palliatives to hold back the descent into the crisis, to attenuate its most brutal expressions, in order to avoid a repetition of what happened in 1929.

- In the period of decadence, credit constitutes an essential means through which the bourgeoisie tries to make up for the lack of extra-capitalist markets. The accumulation of an increasingly uncontrollable global debt, the growing insolvency of the different capitalist sectors and the threat of a profound destabilisation of the world economy are both a consequence and a demonstration of the limits on credit.

- A typical expression of the decadence of capitalism, at the economic level, is the development of unproductive expenditure. This expresses the fact that the development of the productive forces is increasingly held back by the insurmountable contradictions of the system: military expenditure (arms, military operations) to face up to the world wide exacerbation of imperialist tensions; the expenses poured into maintaining and equipping the forces of repression, whose role in the last instance is to deal with the class struggle; advertising, a weapon of the commercial struggle to sell on a glutted market, etc. From the economic point of view, such expenses express a pure loss for capital.

The positions emerging from the debate

Within the ICC, there exists a position which, though compatible with our political platform, is in disagreement with numerous aspects of Rosa Luxemburg's contribution on the economic foundations of the crisis of capitalism.[8] For this position, the foundations of the crisis are to be found in another contradiction highlighted by Marx: the tendency of the rate of profit to fall. While rejecting conceptions (held notably by the Bordigists and councilists) which imagine that capitalism can automatically and eternally generate the expansion of its own market as long as the rate of profit is sufficiently high, it emphasises that the basic contradiction of capitalism is not located in the limits of the market as such (i.e. the form in which the crisis manifest itself) but in the barriers to the expansion of production.

The essentials of the debate around this position have been substantially taken up in polemics with other organisations (even if there are differences in the positions involved) with regard to the saturation of the market and the falling rate of profit.[9]

The other positions expressed in this debate, and which are introduced below, are all based on the analyses of Rosa Luxemburg, and consider the lack of sufficient extra-capitalist markets to play a central role in the crisis and decadence of capitalism.

The critique developed within the organisation of certain contradictions contained within the Decadence pamphlet (notably that post-war reconstruction could in itself make continued accumulation possible by in some way compensating for the lack of markets outside the capitalist system) did not therefore abandon the text's underlying analytical framework. Quite the contrary, it should be considered as a development in the continuity of that framework.

The first of the positions presented here (under the title ‘War economy and state capitalism') though critical of certain aspects of our pamphlet (arguing that it lacks rigour in certain areas and makes no reference to the Marshall Plan in explaining the reconstruction properly so called), still basically adheres to the idea that the prosperity of the 1950s and 60s is determined by the global context of imperialist relations and the establishment of a permanent war economy in the wake of the Second World War.

The two other positions presented here are much more critical of the Decadence pamphlet's analysis of the post-war boom. The first of these (under the title ‘Extra-capitalist markets and debt') re-evaluates and accords a greater significance to these two factors, which have already been analysed by the ICC previously.[10] These two factors are considered sufficient to explain the prosperity of the post-war boom.

The second (under the heading ‘Keynesian-Fordist state capitalism'), starts from the same premise as our pamphlet on decadence - the relative saturation of the markets in 1914 with regard to the needs of accumulation on a world scale - and develops the idea that the system responded to this after 1945 by installing a variant of state capitalism based on a three-fold (Keynesian) repartition of the enormous gains in productivity (Fordism) between profits, state revenues and real wages.

The following sections of this article provide a brief overview of these three positions.[11] In future we will publish more developed expressions of the different positions, or of others that may appear in the debate.

War economy and state capitalism

The point of departure for this position was already made explicit by the Gauche Communiste de France in 1945. The GCF considered that by 1914 the extra-capitalist markets which had supplied capitalism with its necessary field of expansion during its ascendant period were no longer able to play this role: "This historic period is that of the decadence of the capitalist system. What does this mean? The bourgeoisie, which before the first imperialist war lived and could only live through a growing extension of its production, arrived at a point in its history where it could no longer realise this extension (...) Today apart from unusable remote countries, from the derisory ruins of the non-capitalist world, insufficient for absorbing world production, it finds itself master of the world; there are no longer any extra-capitalist markets in front of it, able to serve as new markets for its system. Thus its apogee was also the point at which its decadence began".[12]

Economic history since 1914 is the history of the efforts of the capitalist class, in different countries and at different moments, to overcome this fundamental problem: how to continue to accumulate the surplus value produced by the capitalist economy in a world that has already been divided up by the great imperialist powers and whose market is incapable of absorbing the whole of this surplus value? And since the imperialist powers can no longer expand except at the expense of their rivals, as soon as one war ends they have to prepare for the next one. The war economy has become the permanent way of life of capitalist society; "War production does not aim to solve an economic problem. At its origin is the necessity for the capitalist state to defend itself against the dispossessed classes and to maintain their exploitation by force, and by force to ensure its economic positions and enlarge them at the expense of other imperialist states (...) war production has thus become the crux of industrial production and the principal economic field of society".[13]

The period of post-war reconstruction is a particular moment in this history.

Three economic characteristics of the world in 1945 need to be underlined here:

- firstly, there was the enormous economic and military preponderance of the USA, something more or less without precedent in the history of capitalism. The USA alone represented half of world production and held nearly 80% of world gold reserves. It was the only belligerent country whose productive apparatus came out of the war intact: its gross national product had doubled between 1940 and 1945. It had absorbed all the capital accumulated by the British Empire over years of colonial expansion, plus a good part of the French Empire's as well;

- secondly, there was a keen awareness among the ruling classes of the Western world that it was vital to raise working class living standards if they were to avoid social upheavals that could be used by the Stalinists and thus by the rival Russian bloc. The war economy thus integrated a new aspect, which our predecessors in the GCF were not really aware of at the time: the various social allocations (health, unemployment benefit, pensions, etc) which the bourgeoisie - and above all the bourgeoisie of the Western bloc - put in place at the beginning of the reconstruction period in the 1940s;

- thirdly, state capitalism which, before the Second World War, had expressed a tendency towards autarchy on the part of the different national economies, was now locked into a structure of imperialist blocs which determined the economic relations between states (the Bretton Woods system for the American bloc, COMECON for the Russian bloc).

During the Reconstruction, state capitalism evolved in a qualitative manner: the part played by the state in the national economy became preponderant.[14] Even today, after 30 years of so-called ‘liberalism', state expenditure continues to represent between 30 and 60% of the GNP of the industrialised countries.

This new weight of the state represented a transformation of quantity into quality. The state was no longer just the ‘Executive Committee' of the ruling class; it was also the biggest employer and the biggest market. In the USA, for example, the Pentagon became the main employer in the country (between three and four million people, both civilian and military). As such, it plays a critical role in the economy and makes it possible to exploit existing markets to the hilt.

The setting up of the Bretton Woods framework also made it possible to establish credit systems that were more sophisticated and less fragile than in the past: consumer credit developed and the economic institutions set up by the American bloc (IMF, World Bank, GATT) made it possible to avoid financial and banking crises.

The enormous economic preponderance of the USA enabled the American bourgeoisie to spend without limit in order to ensure its military domination in the face of the Russian bloc: it sustained two bloody and costly wars (in Korea and Vietnam); Marshall-type plans and foreign investment financed the reconstruction of the ruined economies of Europe and Asia (notably in Korea and Japan). But this enormous effort - determined not by the ‘classic' functioning of capitalism but by the imperialist confrontation which characterises the decadence of the system - ended up by ruining the American economy. In 1958 the American balance of payments was already in deficit and in 1970 the USA only held 16% of world gold reserves. The Bretton Woods system was taking in water on all sides, and the world plunged into a crisis from which it has not emerged to this day.

Extra-capitalist markets and debt

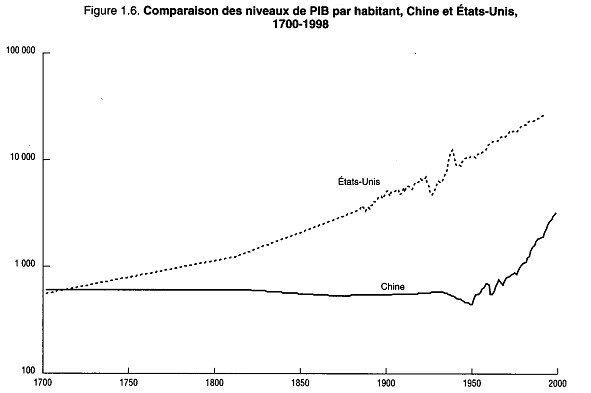

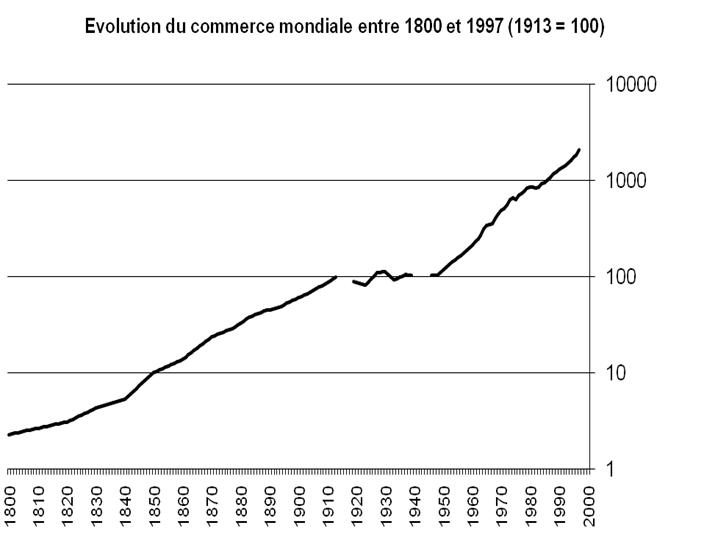

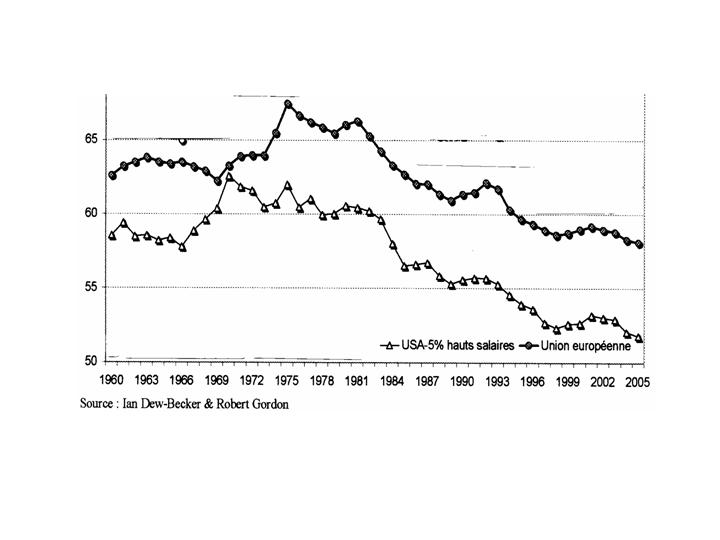

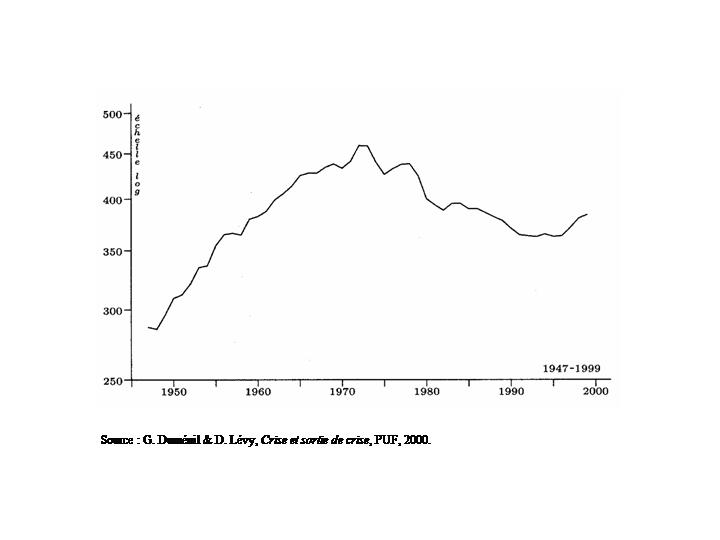

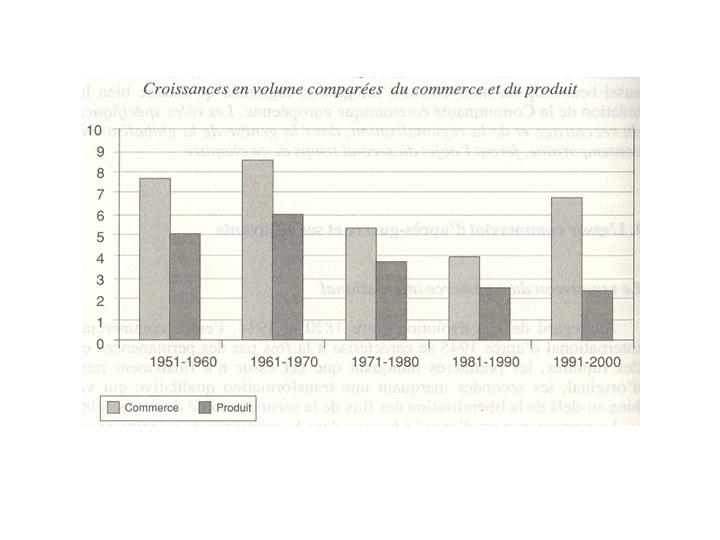

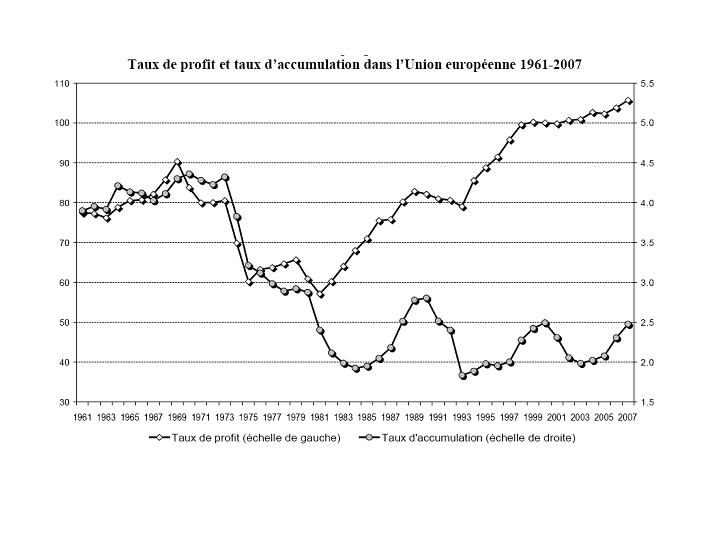

Far from developing the productive forces in a manner comparable to capitalism's ascendancy, the period of the post-war boom was characterised by an enormous waste of surplus value which was a sign that there are barriers to the development of the productive forces, expressing the decadence of the system.