International Review no.19 - 4th quarter 1979

- 3248 reads

The rise in oil prices: an effect not the cause of the crisis

- 3692 reads

Since the end of 1973 western governments and economists have pointed to the rise in oil prices as their main explanation for the economic crisis and its consequences: unemployment and inflation. When companies close down, the workers thrown into the street are told: ‘oil is to blame’; when workers see their real wages shrink under the pressure of inflation, the mass media tells them ‘it’s because of the oil crisis’. The bourgeoisie is using the oil crisis as a pretext, an alibi, to make the exploited swallow the economic crisis. In the propaganda of the ruling class, the oil crisis is presented as a sort of natural disaster men can do nothing about, except passively submit to those calamities called unemployment and inflation.

But ‘nature’ has nothing to do with the fact that oil merchants are now selling their goods at a higher price to other merchants. The oil increase is not nature’s doing but the consequence of capitalist trade relations.

Like all exploiting classes in history, the capitalist class attributes its privileges to the will of nature. The economic laws which make them the masters of society are, in their mind, as natural and unchangeable as the law of gravity. But with time these laws have become outmoded in terms of the productive forces; when their continuation can only cause crises which plunge society into misery and desolation, the privileged class always sees this as ‘nature’s’ fault: nature is not generous enough or there are too many human beings on earth, etc. Never in their wildest imagination would they want to conceive that the existing economic system is at fault, is anachronistic and obsolete.

At the end of the Middle Ages, in the decadence of the feudal system, monks announced the end of the world because the existing fertile lands had been exhausted. Today we are told ten times a day that if everything is going wrong, it is because existing oil sources have been exhausted.

Has nature really run out of oil?

In March 1979, the oil producing countries of OPEC met together to solemnly proclaim that they were going to reduce oil production once again. They are lowering production in order to maintain price levels, just as peasants may destroy their surplus fruit to avoid a collapse in prices.

Europe risks facing an oil scarcity in 1980 they tell us. Perhaps, but who still believes that it is because of a natural, physical scarcity?

The OPEC countries do not produce at capacity, far from it. For several years now new oil fields have been put to use in Alaska, the North Sea, and Mexico. Almost every week new oil deposits are discovered somewhere in the world. Furthermore it is said that oil deposits trapped in shale, in a form more costly to extract, are enormous in comparison to known oil deposits today. How then can we talk about a physical scarcity of oil?

It is perfectly logical to think that one day a certain ore or other raw material will be exhausted because of man’s unlimited use of it. But this has nothing to do with the fact that oil merchants decide to reduce capacity so as to maintain profits. In the first case it really is a question of the end of nature’s bounty; in the second it is simply the case of a vulgar speculative operation on the market.

If the world economic situation was otherwise ‘healthy’, if the only problem was simply the physical and unexpected exhaustion of oil in nature, then we would not be seeing a slowdown in the growth of trade and investment as we do today but a huge economic boom instead: the world’s adaptation to new forms of energy would set off a veritable industrial revolution. Certainly there would be restructuration crises here and there with factories closing down and lay-offs in some sectors, but these closures and lay-offs would find an immediate compensation in the creation of new jobs.

Today we are witnessing something completely different: countries producing oil the most profitably are reducing production; the factories which close are not replaced by new ones; investment in new forms of energy remains negligible in most major countries.

The idea of a physical lack of oil in nature is used by economists and the mass media to explain the dizzying rise of oil prices in 1974 and in 1979. But how can the spectacular rise in the world market prices of all basic materials in 1974 or in 1977 be explained? How can the feverish rise in basic metals like copper, lead, and tin since the beginning of the year be explained? If we follow the ‘experts’ of the bourgeoisie, we would have to believe that oil is not the only thing that is giving out in nature, but also most metals and even food products. Between 1972 and 1974 the price index of metals and ore exported in the world (aside from oil) has more than doubled; food prices have almost tripled. In the second quarter of 1977 these food products cost three times more on the world market than in 1972. We would have to believe that nature is drying up all of a sudden not just in oil but in almost everything else; this is just absurd.

The theory of the physical exhaustion of nature hardly manages to explain the rise in oil prices, but it has even greater difficulty explaining why the real price of oil, as paid by the importing, industrialized countries, (that is the price paid taking into account the growth of world inflation and the evolution of the value of the dollar1 decreased regularly before 1973-74 and afterwards, until 1978. Between 1960 and 1972 the real price of imported crude oil decreased 11% for Japan, 14% for France and 20% for Germany! In 1978 this same price decreased in relation to 1974 or 1975 levels by 14% for Japan, 6% for France and 11% for Germany.

How could the price of a raw material that is supposedly being physically exhausted be diminishing to the point of obliging its producers to artificially reduce their production so as to avoid a collapse of prices?

If we want to understand the present ups and downs in the prices of raw materials we cannot look to the greater or lesser generosity of Mother Nature, but to the decomposition of capitalist trade. We are faced with not the sudden discovery of a grotesque natural scarcity but a huge speculative operation on the raw materials market. This is not a new phenomenon: all major capitalist crises are accompanied by speculative fever in the raw materials market.

Speculation: a typical characteristic of capitalist economic crises

The real source of all capitalist profits resides in the exploitation of workers in the course of the production process. Profit, surplus value, is the surplus labor extracted from wage earners. When everything goes well, that is when what is produced gets sold at a sufficient rate of profit, capitalists reinvest these profits in the production process. The accumulation of capital is this process of transforming the surplus labor of the workers into capital: new machines, new raw materials, new wages, to exploit new quantities of living labor. That is the way capitalists ‘make money work’ as they call it.

But when things are going badly, when production does not give enough of a return because markets are lacking, this mass of capital in money form that is seeking investments, takes refuge in speculative operations. It is not that capitalists prefer this sort of operation where risks are so great that you face ruin from one day to the next; on the contrary they would prefer the ‘peaceful’ road of exploitation through production. But when there is less and less profitable investment available in production, what can you do? Keeping your money in the vault means seeing its value diminish everyday due to monetary erosion. Speculation is a risky placement but it can bring fast and big returns. That is why every capitalist crisis is witness to an extraordinary degree of speculation. The law supposedly prohibits speculation but those who speculate are the very ones who make the laws.

Very often this speculation polarizes around raw materials. In the economic crisis of 1836, Beagle, the director of the US Bank, taking advantage of the fact that the demand for cotton in Great Britain was still strong, bought up the whole cotton crop to sell it at exorbitant prices to the British later. Unhappily for him, the demand for cotton collapsed in 1839 under the pressure of the crisis, and the cotton stocks carefully gathered in the heat of the speculative burst were worthless. Cotton prices collapsed on the world market, adding to the already large number of bankruptcies (1000 banks went bust in the US).

After provoking a speculative price rise in raw materials, the crisis has the effect of collapsing prices because of a lack of demand. These sudden bursts of rising raw material prices followed by a dizzying fall are typical of speculation in a time of crisis. This phenomenon was particularly clear in the crises of 1825, 1836 and 1867 in cotton and wool; in the crises of 1847 and 1857 in wheat; in 1873, 1900 and 1912 in steel and cast-iron; in 1907 in copper; and in 1929 on almost all metals.

Speculation is not the work of isolated, shady individuals operating illegally, or of greedy little stockpilers, as the press likes to paint them. The speculators are governments, nation states, banks large and small, major industries, in short, those who hold most of the monetary mass seeking profits.

In times of crisis speculation is not just a 'temptation' capitalists are capable of avoiding. A banker who has the responsibility of paying interest to thousands of savings accounts has no choice. When profits are getting rare, you have to take them where you can get them. The hypocritical scruples of times of prosperity, when laws are made 'prohibiting speculation', disappear and the most respectable financial institutions throw themselves headlong into the speculative whirlpool. In the capitalist world the one who makes the profits survives. The others are eaten up. When speculation becomes the only way to make profits, the law becomes: he who does not speculate or speculates badly is destroyed.

What is being called the oil crisis is in fact a huge world speculative operation.

Why oil?

Oil has not been the only object of speculation in recent years. Since the devaluation of the pound sterling in 1967, speculation has been increasing in the entire world, attacking an overgrowing list of products: currencies, construction, raw materials (vegetable or mineral), gold, etc. But oil speculation is particularly important because of its financial repercussions. It has set off movements of capital of such size and rapidity as to be largely unprecedented in history. In a few months, a gigantic flow of dollars went from Europe and Japan towards the oil-producing countries. Why did speculation on oil bring such large profits?

First of all because modern industry relies on electricity and electricity relies essentially on oil. No country can produce without oil. Speculation based on the blackmail of an oil shortage is blackmail with economic clout.

But oil is not only indispensable for production and construction. It is also indispensable for destruction and war. Most of the modern arsenal of weapons, from tanks to bombers, from aircraft carriers to trucks and jeeps, works on oil. To arm yourself is not only to produce weapons but to control the means of making these weapons work as long as you need them. The armaments race is also the oil race.

Oil speculation therefore touches a product of primary economic and military importance. That is one of the reasons for its success -- at least for the moment. But it is not the only reason.

The blessing of American capital

One of the favorite themes of the new commentators’ gibberish is the oil crisis as ‘the revenge of the under-developed countries against the rich ones’. By a simple decision to reduce their production and raise the price of oil, these countries, who are part of the victims of the third world, previously condemned to produce and sell raw materials cheaply to the industrialized countries, have got the great powers by the throat. A real David and Goliath story for our times!

Reality is quite another thing. Behind the oil crisis is US capital. Just consider two important and obvious facts:

1. The major powers of OPEC are very strongly under the domination of US imperialism. The governments of Saudi Arabia, the major oil exporter in the world, of Iran in the time of the Shah, or Venezuela, to take only a few examples, do not make any crucial decisions without the agreement of their powerful ‘protector’.

2. Almost all world trade in oil is under the control of the large American oil companies. The profits made by these companies, because of the variations in oil prices, are so enormous that the US government recently had to organize a parody of government hearings on the television to divert the anger of a population which is feeling the effects of austerity programs justified by the ‘oil crisis’ onto the ‘Seven Sisters’ -- the major oil companies.

If this is not enough to prove the decisive role played by the US in the oil price rises, consider some of the advantages the strongest economic power drew from the ‘oil crisis’:

1. On the international market, oil is paid in US dollars. Concretely this means that the US can buy oil simply by printing more paper money, while other countries have to buy dollars.2

2. The US imports only 50% of the oil it needs. Their direct competitors on the world market -- Europe and Japan -- have to import almost all their oil; any price rise in oil therefore has a much greater effect on production costs of European and Japanese goods. The competitiveness of US goods is thus automatically increased. It is not an accident that US exports have increased enormously after each oil price rise to the detriment of their competitors.

3. But it is surely on the military level that the US has benefited the most from the oil crisis.

As we have seen, oil remains a major instrument of war. The oil price rise allowed for the profitable exploitation of new oil fields in or near the US (Mexico, Alaska and other US deposits). In this way US military potential is less dependent on oil deposits in the Middle East which are far from Washington, and close to Moscow. In addition, the huge oil revenues have financed the ‘Pax Americana’ in the Middle East through the intermediary of Saudi Arabia. In fact Egypt’s costly passage into the US bloc was partly paid for through aid from Saudi Arabia in the name of Arab brotherhood. Saudi Arabia directly influenced the policy of countries like Egypt, Iraq, Syria (during the Lebanon conflict) through their economic ‘aid’ financed out of oil revenues. Saudi Arabian financial aid to the PLO is not entirely foreign to the budding rapprochement between the PLO and the US bloc.

American imperialism has thus given itself the luxury of having its competitors and allies, Europe and Japan, finance its international policy. Thus for economic and military reasons the US has an interest in letting oil prices rise and even encouraging this.

The attitude of the Carter government during the burst of speculation brought on by the interruption of deliveries from Iran is very indicative. While Germany and France were trying to choke off the speculation developing on the ‘free market’ in Rotterdam in the first half of 1979, the US government cynically announced it was prepared to buy any amount of oil at a higher price than any reached at the Dutch port. Despite special envoys from Bonn and Paris, sent to Washington to protest against this ‘knife in the back’, the White House would not go back on its offer.

Whatever the different reasons for the price rise, one issue remains: what are the effects on the world economy? Is the official propaganda right in saying that the oil crisis is responsible for the economic crisis?

The effects of the oil price rise

There is no doubt that the rise in the price of raw materials is a handicap for the profitability of any capitalist enterprise. For industrial capital raw materials constitute an overhead expense. If expenses increase, the profit margin proportionally decreases. Industrial capital has only two ways of fighting against this decline in profits:

-- reducing overhead costs in other ways especially by reducing the price of labor;

-- compensating for overhead costs by increasing the sale price.

Capitalists usually use the two methods at the same time. They try to reduce their overheads by imposing austerity policies on the workers; they try to maintain profits by increasing prices and thus fuelling inflation. Thus it is certain that the oil price rise is a factor forcing each national capital to make new efforts towards maximizing profits: eliminating the least productive sectors, reducing wages, concentrating capital further. It is thus true that oil prices are partly responsible for increased inflation.

The oil increase is indeed an exacerbating factor in the crisis. But contrary to what the propaganda of the media disseminates, it was only that -- an exacerbating factor and not the cause or even the major cause of the economic crisis.

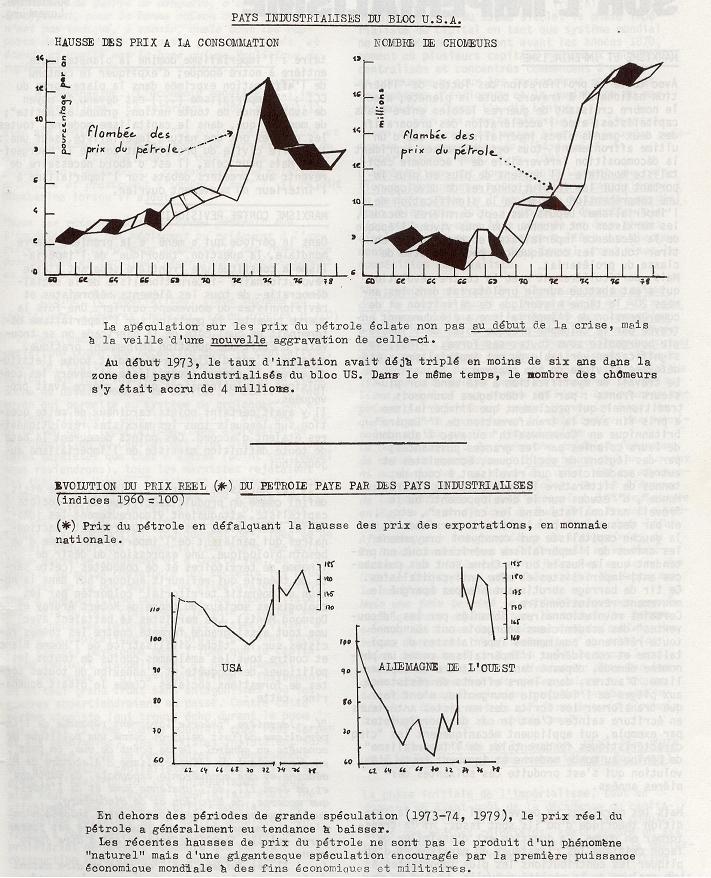

The economic crisis did not begin with the oil increases. Oil speculation is merely one of the consequences of the economic disorders which have plagued capitalism since the end of the 1960s. To hear bourgeois ‘experts’ speak, one would think that before the fatal date of the second half of 1973 everything was rosy in the world economy. To justify their austerity policies, these gentlemen forget or pretend to forget that at the beginning of 1973, before the big oil price increases, the inflation rate had doubled in the US and tripled in Japan in less than a year. They pretend to forget that between 1967 and 1973 capitalism went through two serious recessions: one in 1967 (the annual growth rate of production fell by half in the US -- 1.8% in the first half of 1967 -- and fell to zero in Germany), and the other in 1970-71 when production declined absolutely in the US. They forget or hide the fact that the number of unemployed in the OECD countries (the twenty-four industrialized countries of the US bloc) had doubled in six years, from 6 million and a half in 1966 to more than 10 million in 1972. They ignore the fact that at the beginning of 1973, after six years of monetary instability that began with the devaluation of the pound in 1967, the international monetary system definitively collapsed with the second devaluation of the dollar in two years.

The speculation in oil did not burst in upon a serene and prosperous capitalist economy. On the contrary, it appeared as yet another convulsion of capitalism shaken for the past six years by the deepest crisis since World War II.

It is absurd to explain the difficulties of the 1967 to 1973 period by the oil price rises which followed it in 1974; it is just as absurd to consider the oil price increase as the cause of the economic crisis of capitalism.

*******************

Oil speculation dealt a blow to the world economy but it was neither the first nor the most serious one. The purely relative importance of the blow can be measured ‘negatively’ so to speak by considering the situation in an industrialized country which has managed to eliminate the oil problem by exploiting its own deposits. Such is the case of Great Britain which is less dependent on oil imports because of its fields in the North Sea. In 1979 the rate of unemployment was twice that of Germany and three times the rate in Japan -- two countries which nevertheless have to import almost all their oil. Inflation of consumer prices in Great Britain is double Germany’s and nine times greater than Japan’s. And finally, the growth rate of production is the weakest of the seven major western powers (in the first half of 1979 gross production had not increased but decreased by 1% in annual terms) .

The causes of the present crisis of capitalism are much more profound than the consequences of oil speculation. Since the beginning of the 1960s capitalism has been in a headlong race to escape the consequences of the end of the period of reconstruction. For more than ten years the industrial regions destroyed in World War II have not only been reconstructed -- thereby eliminating one of the major markets for US exports -- but have become powerful competitors of the US on the world market. The US has become a country which exports less than it imports and therefore must cover the world with its paper money to finance its deficit. For ten years, since the end of the reconstruction process, world growth has been resting essentially on credit sales to underdeveloped countries and on the US’ ability to finance its deficit. However, both the former and the latter are on the brink of financial bankruptcy.

The debt of the third world countries has reached unbearable proportions (the equivalent of the annual revenue of a thousand million men in these regions). The US is heading into a recession as a way to reduce their imports and stop the growth of their debts. The recession beginning in the US is inevitably the sign of a world recession, a recession which according to the observable progression from 1967 onwards will be deeper than the three previous ones.

Speculation on the price of oil is only a secondary aspect of a much more important reality: the fact that capitalist production relations are definitively out of step with the possibilities and needs of humanity.

After almost four centuries of world domination, capitalist laws have exhausted their validity. From being a progressive force, they have become an obstacle to the very survival of humanity.

It is not the ‘Arabs’ who have brought capitalist production to its knees. Capitalism is economically collapsing because it is increasingly undermined by its internal contradictions, and mainly by its inability to find enough markets to sell its production profitably. We are living at the end of a round in the cycle of crisis-war-reconstruction which capitalism has imposed on humanity for more than sixty years.

For humanity the solution is not to be found in lowering the price of oil nor in lowering wages but in eliminating wage slavery, in eliminating the capitalist system east and west.

Only with a new form of organization for world society, following real communist principles, will we escape the endless barbarism of capitalism in crisis.

R. Victor

1 The fact that the price of oil increasing is not significant in itself because world inflation affects all products and revenues. For an oil-importing country the real question is whether or not the price of oil is increasing slower or faster than the price of other exports. For an oil-importing country the rise in oil prices has a negative effect only to the extent that it rises faster than that of prices of other commodities which it exports, that is to say, the source of its own revenues on the world market. What difference does it make to pay 20% more for oil if one’s own export prices can be raised by the same amount at the same time?

2 The danger of new pressures towards devaluation of the dollar because of the new volume of paper money put into circulation by the US is relatively limited by the increase in the demand for dollars provoked by the rise in oil prices.

Historic events:

- oil crises 1973 [1]

On Imperialism

- 5808 reads

With the proliferation of ‘national liberation' struggles all over the planet; with the increasing number of local wars between capitalist states, with the accelerating preparations of the two great imperialist blocs for a final confrontation - all of these phenomena expressing the irreversible decomposition of the capitalist world economy - it becomes more and more important for revolutionaries to develop a clear understanding of the meaning of imperialism. For the last seven decades, marxists have recognised that we are living in the epoch of imperialist decay and have attempted to draw out all the consequences of the imperialist epoch of the class struggle of the proletariat. But - particularly with the onset of the counter-revolution which descended on the proletariat in the 1920's - the theoretical task of defining and understanding imperialism has been severely hampered by the almost unchallenged triumph of bourgeois ideology in all its forms. Thus the very meaning of the word imperialism has been distorted and undermined. This work of mystification has been carried out on several fronts: by the traditional bourgeois ideologues who declare that imperialism came to an end when Britain changed its ‘Empire' into a ‘Commonwealth', or when the great powers abandoned their colonies; by hosts of sociologists, economists, and other academics who vie with each other to produce ever-mounting piles of unreadable literature about the ‘Third World', ‘Development Studies', the nationalist awakening in the colonies, etc.; above all by the pseudo-marxists of the capitalist left, who loudly lambaste the crimes of US imperialism while pretending that Russia or China are non-imperialist and even anti-capitalist powers. This stultifying barrage has not left the revolutionary movement unscathed. Some revolutionaries, taken in by the ‘discoveries' of bourgeois academics, have abandoned all reference to capitalism's imperialist drives and see imperialism as an outmoded, superseded phenomenon in capitalism's history. Others, in their effort to resist the encroachments of bourgeois ideology, simply turn the writings of previous marxists into holy writ. This is the case with the Bordigists for example, who mechanically apply Lenin's ‘five distinguishing characteristics of imperialism' to the modern world, ignoring all the developments that have taken place over the last sixty years.

But marxists can neither ignore the theoretical tradition from which they come, nor turn it into a dogma. It's a question of critically assimilating the classics of marxism and applying the richest contributions to an analysis of present-day reality. The aim of this text is to draw out the real and contemporary meaning of the elementary formulation: imperialism dominates the entire planet in this epoch. We aim to give substance to the contention, expressed in the ICC's platform, that "imperialism... has become the means of survival for every nation no matter how large or small"; to show that, under modern capitalism, all wars have an imperialist nature, save one: the civil war of proletariat against the bourgeoisie. But to do this it is necessary first to refer back to the original debates on imperialism within the workers' movement.

MARXISM AGAINST REVISIONISMIn the period leading up to the First World War, the ‘theoretical' question of imperialism constituted a dividing line between the revolutionary, international wing of social democracy, and all the revisionist and reformist elements in the workers' movement. With the outbreak of the war your position on imperialism determined which side of the barricade you were on. It was an eminently practical question, because on it depended your whole attitude towards the imperialist war, and towards the revolutionary convulsions which the war provoked.

There were in this matter certain cardinal points upon which all revolutionary marxists agreed. These points remain the foundations of any marxist definition of imperialism today.

1) For marxists, imperialism was defined as a specific product of capitalist society; they vigorously attacked the more overtly reactionary bourgeois ideologies which portrayed imperialism as a biological urge, as an expression of man's innate desire for territory and conquest (the sort of theory which flourishes again today in the notion of the ‘territorial imperative' peddled by social zoologists like Robert Ardrey and Desmond Morris). The marxists fought with equal tenacity against racist theories about the White Man's Burden, and against all confusionist amalgams of all policies of conquest and annexation in all kinds of social formations. As Bukharin put it, this:

"...very widespread ‘theory' of imperialism defines it as the policy of conquest in general. From this point of view one can speak with equal right of Alexander the Macedonian's and the Spanish conqueror's imperialism, of the imperialism of Carthage and Ivan III, of ancient Rome and modern America, of Napoleon and Hindenburg.

"Simple as this theory may be, it is absolutely untrue. It is untrue because it ‘explains' everything, i.e. it explains absolutely nothing... the same can be said about war. War serves to reproduce those relations on a wider scale. Simply to define war, however, as conquest, is entirely insufficient, for the simple reason that in doing so we fail to indicate the main thing, namely, what production relations are strengthened and extended by the war, what basis is widened by a given ‘policy of conquest" (Imperialism and World Economy, Merlin Press, Chapter 9, p.112-113).

Although Lenin said that "colonial policy and imperialism existed before this latest stage of capitalism, and even before capitalism. Rome founded on slavery, pursued a colonial policy and practised imperialism", he concurs with Bukharin when he adds "general disquisitions on imperialism, which ignore, or put into the background, the fundamental differences between socio-economic systems, inevitably degenerate into the most vapid banality or bragging" "Imperialism, Highest Stage of Capitalism, Peking, Chapter VI, p.97).

2) Secondly, marxists defined imperialism as a necessity for capitalism, as a direct result of the accumulation process, of capital's innermost laws. At a given stage in the development of capital, it was the only way in which the system could prolong its life. It was thus irreversible. Although the explanation of imperialism as an expression of capital accumulation is clearer in some marxists than others (a point we shall be returning to), all marxists rejected the thesis of Hobson, Kautsky and others who saw imperialism as a mere ‘policy' chosen by capitalism or rather by particular factions of capitalism. This thesis was logically accompanied by the idea that you could prove that imperialism was a bad, short-sighted, expensive policy and that you could at least convince the more enlightened sections of the bourgeoisie that they would be better of f with a sensible, non-imperialist policy. This clearly paved the way for all kinds of reformist pacifist recipes aimed at rendering capitalism less brutal and less aggressive. Kautsky even developed the idea that capitalism was moving gradually and peacefully into a phase of ‘ultra-imperialism', fusing into one big non-antagonistic trust where wars would be a thing of the past. Against this utopian view (echoed during the post-World War Two boom by the likes of Paul Cardan) the marxists insisted that far from representing a transcendence of capitalism's antagonisms, imperialism expressed the sharpening of these antagonisms to their highest degree. The imperialist epoch was inevitably one of world crises, political despotism and world war; faced with this catastrophic perspective, the proletariat could only respond with the revolutionary destruction of capitalism.

3) Thus imperialism was seen as a specific phase of capital's existence: its highest and final phase. Although it is permissible to talk of, say, British and French imperialism in earlier parts of the century, the imperialist phase of capital as a world system does not truly begin until the 1870s, where several highly centralised and concentrated national capitals began to compete for colonial possessions, spheres of military influence and domination of the world market. As Lenin said, "an essential feature of imperialism is the rivalry between several Great Powers in the striving for hegemony" (Imperialism, Chapter 5, p.109). Imperialism is thus essentially a competitive relationship between capitalist states at a certain stage in the evolution of world capital. Furthermore, the development of this relationship can itself be seen to have two distinct phases, which are directly linked to changes in the global milieu in which imperialist competition takes place.

"The first period of imperialism was the last quarter of the 19th century and followed on from the epoch of national wars through which the constitution of the great national states was achieved, the terminal point of this epoch being the Franco-Prussian war. If the long period of economic depression following the crisis of 1873 already bore the seeds of the decadence of- capitalism, capital could still use the short recoveries which occurred during the depression to complete the exploitation of backward territories and peoples. Capitalism in its avid, feverish hunt for raw materials and buyers who are neither capitalists nor wage labourers, robbed, decimated and murdered the colonial populations. This was the epoch of the penetration and extension of Britain into Egypt and South Africa, France into Morocco, Tunis and Tonkin, Italy into East Africa and the frontiers of Abyssinia, Tsarist Russia into central Asia and Manchuria, Germany into Africa and Asia, the USA into the Philippines and Cuba, and Japan into the Asian continent.

"But once these great capitalist groupings had completed the division of all usable land, all the exploitable wealth, all spheres of influence, in short all the corners of the world where labour power could be pillaged, transformed into gold, and piled up in the national banks of the metropoles, then capitalism's progressive mission came to an end... it's then that the genera1 crisis of capitalism had to open up." (Le Problème de la Guerre, 1935, by Jehan, a militant of the Belgian Communist Left)

The initial phase of imperialism, while giving a foretaste of capitalism's decay and bringing blood and misery to the populations of the colonial regions, still had a progressive aspect to it, in that it was establishing the world wide dominion of capital - the precondition for the communist revolution. But once this world-wide domination was achieved, capitalism ceased to be a progressive system, and the catastrophes it had brought to the colonial peoples now rebounded to the heart of the system, as the outbreak of World War 1 confirmed:

"Modern imperialism is not the prelude to the expansion of capital... it is only the last chapter of its historical process of expansion; it is the period of universally sharpened world competition between the capitalist states for the last remaining non-capitalist areas on earth. In this final phase, economic and political catastrophe is just as much the intrinsic normal mode of existence for capital as it was in the ‘primitive accumulation' of its development stage... the economic expansion of capital in its imperialist final phase is inseparable from the series of colonial conquests and World Wars we are now experiencing. What distinguishes imperialism as the last struggle for capitalist world domination is not simply the remarkable energy and universality of expansion but - and this is the specific sign that the circle of development is beginning to close - the return of the decisive struggle for expansion from those areas which are being fought over back to its home countries. In this way, imperialism brings catastrophe as a mode of existence back from the periphery of capitalist development to its point of departure. The expansion of capital, which for four centuries had given the existence and civilisation of all non-capitalist peoples in Asia, Africa, America and Australia over to ceaseless convulsions and general and complete decline, is now plunging the civilised peoples of Europe into a series of catastrophes whose final result can only be the decline of civilization or the transition to the socialist mode of production." (Luxemburg, The Anti-critique).

Capitalism in its final imperialist phase was the "epoch of wars and revolution" recognised by the Communist International, an epoch in which humanity was faced with the stark choice between socialism or barbarism. For the working class the epoch meant the obliteration of all the reforms it had won in the 19th century and a mounting attack on its living standards through austerity and war. Politically it meant the destruction or recuperation of its previous organisations and the ruthless oppression of the leviathan imperialist state, compelled by the logic of imperialist competition and by the decomposition of the social fabric to take in hand every aspect of social, political and economic life. That is why, faced with the slaughter of World War 1, the revolutionary left concluded that capitalism had definitely outplayed its historic role, and that the immediate task of the international working class was to turn the imperialist war into civil war, to overthrow imperialism by striking at the root of the problem: the world capitalist system. Naturally this meant a complete rupture with the social democratic traitors who, like the Scheidemanns and Millerands, had become open, chauvinist advocates of imperialist war, or the ‘social-pacifists' like Kautsky, who continued to spread the illusion that capitalism could exist without imperialism, without dictatorship, terror and war.

THE DEBATE BETWEEN MARXISTSThus far there could be no disagreement among the marxists, and indeed these basic points of agreement were sufficient basis for the regroupment of the revolutionary vanguard in the Communist International. But the disagreements which existed then and still exist today in the revolutionary movement arose when marxists tried to make a more precise analysis of the driving force behind imperialism and of its concrete manifestations, and when they drew the political consequences from this analysis. These disagreements tended to correspond to different theories about the capitalist crisis and the historical decline of the system, since imperialism, as all agreed, was capital's attempt to offset its mortal contradictions. Thus Bukharin and Luxemburg, for example, emphasized different contradictions in their theories of the crisis, and thus gave differing accounts of the driving force behind imperialist expansion. This debate was further complicated by the fact that the bulk of Marx's work on economics had been written before imperialism had really established itself, and this gap in his work gave rise to different interpretations of the way Marx's writings should be applied to the analysis of imperialism. It is impossible in this text to go back over all these debates about the crisis and imperialism, most of which remain unresolved today. What we want to do is examine briefly the two main definitions of imperialism developed during the period - those of Lenin/Bukharin and Rosa Luxemburg - and to judge how adequate are these definitions both for that time and for the present period. In doing so we will attempt to make more concise our own conception of imperialism today.

LENIN'S CONCEPTION OF IMPERIALISMFor Lenin, the characteristic features of imperialism were:

"1) The concentration of production and capital has developed to such a high stage that it has created monopolies which play a decisive role in economic life;

2) the merging of bank capital with industrial capital and the creation, on the basis of this ‘finance capital', of a financial oligarchy;

3) the export of capital as distinguished from the export of commodities acquires exceptional importance;

4) the formation of international monopolist capitalist combines which share the world among themselves;

5) the territorial division of the whole world among the biggest capitalist powers is completed."

(Imperialism, chap 7, p.106)

Although Lenin's definition of imperialism contains a number of important indicators, its main weakness is that it is more a description of some of imperialism's outward effects, than an analysis of the roots of imperialism in the accumulation process. The organic or intensive development of capital into more and more concentrated units, and the geographic or extensive development of capital's field of activity (the search for colonies, territorial division of the globe) are fundamentally expressions of the inner processes of accumulation. It is the growing organic composition of capital, with the corresponding fall in the rate of profit and shrinking of the domestic market, which compelled capital to seek new profitable outlets for capital investment and to extend continuously the market for its commodities. But while the underlying dynamic of imperialism does not change, the outward manifestations of this dynamic are subject to modification, so that many aspects of Lenin's definition of imperialism are inadequate today, and were even at the time he was elaborating it. Thus the period in which capital could be seen to be dominated by an oligarchy of "finance capital" and by "international monopolist combines" was already giving way to a new phase during World War 1 - the period of state capitalism, of the permanent war economy. In the epoch of chronic inter-imperialist rivalries on the world market, the entire national capital tends to be concentrated around the state apparatus, which subordinates and disciplines all particular factions of capital to the needs of military/economic survival. The recognition that capitalism had entered an epoch of violent struggles between national "state capitalist trusts" was much clearer to Bukharin than Lenin (see Imperialism and World Economy), though Bukharin was still constrained by the equation of imperialism with finance capital, so that his "state capitalist trust" is, to a large extent, presented as a ‘tool' of the financial oligarchy, whereas the state is actually the supreme directing organ of capital in this epoch. Furthermore, as Bilan pointed out,

"To define imperialism as a ‘product' of finance capital, as Bukharin has done, is to establish a false connection and above all is to lose sight of the common origin of these two aspects of the capitalist process: the production of surplus value." (Mitchell, ‘Crisis and Cycles in the Economy of Capitalism in Agony' Bilan no. 11, 1934)

Lenin's failure to understand the significance of state capitalism was to have grave political consequences in a number of areas: illusions in the progressive nature of certain aspects of state capitalism, applied with disastrous consequences by the Bolsheviks in the Russian Revolution; the inability to see the integration of the old worker's organisations into the state, and the evasive theory of the Labour Aristocracy and of ‘bourgeois workers parties' and ‘reactionary unions' which are somehow distinct from the state machine (the problem with these organisations wasn't simply that a large number had been bribed by ‘imperialist super profits', as Lenin argued, but that the entire apparatus had been incorporated into the colossus of the imperialist state). The tactical conclusions which were drawn from these erroneous theories are well known: the united front, trade union work, etc... Similarly Lenin's emphasis on colonial possessions as a distinguishing and even indispensable feature of imperialism has not stood the test of time. Despite his expectation that the loss of the colonies, precipitated by national revolts in these regions, would shake the imperialist system to its foundations, imperialism has adapted quite easily to ‘decolonisation'. Decolonisation simply expressed the decline of the older imperialist powers, and the triumph of imperialist giants who were not burdened with many colonies in the period around World War 1. Thus the USA and Russia were able to develop a cynical ‘anti-colonial' line to further their own imperialist ends, to batten onto national movements in the colonies and transform them immediately into inter-imperialist proxy-wars.

Lenin's theory of imperialism became the official position of the Bolsheviks and the Communist International, particularly in relation to the national and colonial question, and it is here that the defects of the theory were to have their most serious ramifications. When imperialism is characterised by essentially super-structural features, it becomes easy to divide the world into imperialist, oppressing nations and oppressed, non-imperialist nations, and even for certain imperialist powers to abruptly ‘cease' being imperialist when they shed one or more of these defining characteristics. Along with this went a tendency to obscure class differences in the ‘oppressed nations' and to argue that the proletariat - as the national champion of all the oppressed - had to rally these oppressed nations to its revolutionary banner. This position was applied mainly to the colonies, but in his critique of The Junius Pamphlet, Lenin argued that even developed capitalist countries in modern Europe could, under certain circumstances fight a legitimate war for national independence. During the First World War this ambiguous idea was inoperative because of Lenin's correct evaluation that the overall imperialist context of the war made it impossible for the proletariat to support a policy of national defence in any of the belligerents. But the weakness of the theory were starkly demonstrated after the war, above all with the decline of the revolutionary wave and the isolation of the Soviet State. The idea of the anti-imperialist, character of the ‘oppressed nations' was refuted by the events in Finland, Eastern Europe, Persia, Turkey and China, where the attempt to carry out the policies of ‘national self-determination' and the anti-imperialist united front' was powerless to prevent the bourgeoisies of these countries from allying themselves with the imperialist powers and crushing any initiative towards the communist revolution[1].

Perhaps the most grotesque application of the ideas that Lenin had advanced in his On the Junius Pamphlet was in Germany during the ‘National Bolshevik' experiment in 1923: according to this debased concept, Germany suddenly ceased to be an imperialist power because it had been deprived of its colonies and was being plundered by the Entente. An anti-imperialist alliance with sections of the German bourgeoisie was therefore on the agenda. Of course, there is no straight line from Lenin's theoretical weaknesses to these outright betrayals; a whole process of degeneration lay between them. Nevertheless it is important for communists to demonstrate that it is precisely the errors of past revolutionaries that can be used by degenerating or counter-revolutionary parties to justify their treason. It is not accidental that the counter-revolution, in its Stalinist, Maoist or Trotskyist forms, makes abundant use of Lenin's theories of imperialism and national liberation to ‘prove' that Russia or China are not imperialist (see the typical leftist trick: ‘where are the monopolies and financial oligarchies in Russia?'); or, equally to ‘prove' that numerous bourgeois gangs in the underdeveloped countries must be supported in their ‘anti-imperialist' struggle. It's true that they distort and corrupt many aspects of Lenin's theory, but communists should not be afraid to admit that there are numerous elements in Lenin's conception which can be taken more or less ‘straight' by these bourgeois forces. It is precisely these elements which we must be able to criticize and go beyond.

IMPERIALISM AND THE FALLING RATE OF PROFITWith Lenin, it is merely implicit that imperialist expansion was rooted in the accumulation process - in the need to offset the falling rate of profit by seeking cheap labour and raw materials in the colonial regions. This element is more explicitly drawn out by Bukharin, and it is perhaps not accidental that Bukharin's more rigorous analysis of imperialism was, initially at least, accompanied by a clearer position on the national question (during World War I and the first years of the Russian Revolution Bukharin argued against Lenin's position on national self-determination. Later on he changed his position; it was Luxemburg's position on the national question - intimately linked to her theory of imperialism[2] - which proved to be the most consistent). Without doubt, the need to offset the falling rate of profit was a cardinal element in imperialism, because imperialism begins precisely at that stage when a number of national capitals with a high organic composition come to the foreground of the world market. But although we cannot deal with the question at any length here[3], we consider that explanations of imperialism which refer more or less exclusively to the falling rate of profit suffer from two major weaknesses:

1. Such explanations tend to portray imperialism as the unique expression of a few highly developed countries - countries with a high organic composition of capital, forced to export capital in order to offset the falling rate of profit. This view has reached a level of caricature with the CWO, who equate imperialism with economic and political independence and conclude that there are now only two imperialist powers in the world - the USA and Russia - since they alone are truly ‘independent' (other countries merely have ‘imperialist' tendencies' which can never be realized). This is the logical outcome of looking at the problem from the point of view of individual capitals, rather than of global capital. For, as Rosa Luxemburg stressed:

"Imperialism is not the creation of any one or any group of states. It is the product of a particular stage of ripeness in the world development of capital, an innately international condition, an indivisible whole, that is recognisable only in all it€ relations, and from which no nation can hold aloof at will." (The Junius Pamphlet)

This does not mean that the CWO's conclusion is the inevitable result of explaining Imperialism solely with reference to the falling rate of profit. If one begins from the standpoint of global capital, it becomes clear that, just as it is the rate of profit in the most developed capitals which determines the global rate of profit, so the consequent imperialist behaviour of the advanced capitals must also have its echo among the weaker capitals. But the minute you do regard the problem of imperialism from the standpoint of global capital, you become aware of another contradiction in the cycle of accumulation - the inability of global capital to realize all the surplus value within its own relations of production. This problem, posed by Luxemburg in The Accumulation of Capital was dismissed by Lenin, Bukharin and their followers as an abandonment of marxism, but it is not hard to show that Marx was preoccupied with the same problem[4]:

"The more capitalist production develops, the more it is forced to produce on a scale which has nothing to do with the immediate demand but depends on a constant expansion of the world market. He (i.e. Ricardo) has recourse to Say's trite assumption, that the capitalist produces not for the sake of profit, surplus value, but produces use-value directly for consumption - for his own consumption. He overlooks the fact that the commodity has to be converted into money. The demand of the workers does not suffice, since profit arises precisely from the fact that the demand of the workers is smaller than the value of their product, and that it (profit) is all the greater, the smaller, relatively, is this demand. The demand of the capitalists among themselves is equally insufficient." (Marx, ‘Ricardo's Theory of Profit", Theories of Surplus Value, Part 2, chap XVI, p.468)

2. Thus any serious analysis of imperialism must take into account this necessity for the "constant expansion of the world market". A theory which ignores the problem is unable to explain why it was precisely at the point that the world market was unable to continue expanding - with the integration of the most important sectors of pre-capitalist economy into the capitalist pre-capitalist economy into the capitalist world economy around the beginning of the 20th century - that capitalism plunged into the permanent crisis of its final imperialist period. Can the historical simultaneity of these two phenomena be dismissed as a mere coincidence? While all marxist analyses of imperialism saw that the hunt for cheap raw materials and labour power was a central aspect of colonial conquest, only Luxemburg understood the decisive importance of the pre-capitalist markets of the colonies and semi-colonies, since they provided the soil for the "constant expansion of the world market" until the early years of the twentieth century. And it is precisely this element which is the ‘variable' in the analysis. Capital can always find cheap labour power and raw material in the underdeveloped regions: this was true both before and after the incorporation of the colonies and semi-colonies into the capitalist world economy, both in the ascendant and decadent phases of capital. But once the solvent demand of the regions ceases to be ‘extra-capitalist', once the bulk of it is integrated into capitalist relations of production, global capital has no new outlets for the realisation of that fraction of the surplus value earmarked for accumulation. It has lost its capacity to continuously expand the world market. Now the ‘colonial regions' are themselves producers of surplus value, competitors with the metro- poles. Labour power and raw materials in these regions may still remain cheap, they may remain areas of profitable investment, but they no longer help world capital with its problems of realisation: they have become part of the problem. Moreover, this incapacity to expand the world market to anything like the degree required by the productivity of capital also deprives the bourgeoisie of one of the main counter-tendencies to the falling rate of profit: increasing the mass of profit by producing and selling an increased amount of commodities. Thus the predictions of the Communist Manifesto are borne out:

"The conditions of bourgeois society are too narrow to comprise the wealth created by them. And how does the bourgeoisie get over these crises? On the one hand by enforced destruction of a mass of productive forces; on the other, by the conquest of new markets, and by the more thorough exploitation of the old ones. That is to say, by paving the way for more extensive and destructive crises, and by diminishing the means whereby crises are prevented."

It is Rosa Luxemburg's theory of imperialism which most clearly continues Marx's thought on this question.

LUXEMBURG'S CONCEPTION OF IMPERIALISM - AND ITS CRITICS"Imperialism is the political expression of the accumulation of capital in its competitive struggle for what remains still open of the non-capitalist environment. Still the largest part of the world in terms of geography, this remaining field for the expansion of capital is yet insignificant as against the high level of development already attained by the productive forces of capital; witness the immense masses of capital accumulated in the old countries which seek an outlet for their surplus product and strive to capitalize their surplus value, and the rapid change-over to capitalism of the pre-capitalist civilisations. On the international stage, then, capital must take appropriate measures. With the high development of the capitalist countries and their increasingly severe competition in acquiring non-capitalist areas, imperialism grows in lawlessness and violence, both in aggression against the non-capitalist world and in ever more serious conflicts among the competing capitalist countries. But the more violently, ruthlessly and thoroughly imperialism brings about the decline of non-capitalist civilisations, the more rapidly it cuts the very ground from under the feet of capitalist accumulation. Though imperialism is the historical method for prolonging the career of capitalism, it is also a sure means of bringing it to a sure conclusion. This is not to say that capitalist development must be actually driven to this extreme: the mere tendency towards imperialism of itself takes forms which make the final phase of capitalism a period of catastrophe." (Luxemburg, Accumulation of Capital, chap 31, p.446)

As can be seen from this passage, Luxemburg's definition of imperialism concentrates on the basic terms of the problem, viz, the accumulation process, and in particular the phase of the process concerned with realization, rather than on the super-structural ramifications of imperialism. Elsewhere, however, she shows that the political corollary of imperialist expansion is the militarization of society and the state: the exhaustion of bourgeois democracy and the development of openly despotic forms of capitalist rule; the brutal depression of workers' living standards in order to maintain the grossly inflated military sector of the economy. Although the Accumulation of Capital contains some contradictory ideas about militarism as a "province of accumulation", Luxemburg was basically correct in seeing the war economy as an indispensable characteristic of imperialistic, declining capitalism. But Luxemburg's basic analysis of the driving force behind imperialism has been the subject of numerous criticisms. The most important of these was written by Bukharin in his Imperialism and the Accumulation of Capital (1924). The bulk of his arguments against Luxemburg's theory have been echoed recently by the CWO (see RP 6 ‘The Accumulation of Contradictions'.) We want to deal here with the two most important criticisms raised by Bukharin.

1) According to Bukharin, Luxemburg's theory that imperialism is motivated by the search for new markets makes the imperialist epoch indistinguishable from all previous epochs of capital:

"Trade capitalism and mercantilism, industrial capitalism and liberalism, finance capital and imperialism - all these phases of capitalist development disappear or dissolve into capitalism as such". (Imperialism and the Accumulation of Capital, chap 4, p.253)

And for the CWO,

"...her rationale for imperialism based on ‘saturated markets' is extremely weak and inadequate. If, as Luxemburg admitted... the capitalist metropoles still contained pre-capitalist enclaves (e.g. serfs, peasants) why does capitalism have to expand overseas and away from the capitalist metropoles from the very beginning of its existence? Why doesn't it first bring all the areas closest at hand within the capital-wage labour relationship if it merely seeks for new markets? The explanation is to be found not in the need for new markets but in the search for raw materials and the maximisation of profit. Second, Luxemburg's theory implies that imperialism is a permanent characteristic of capitalism. As capitalism, for Luxemburg, has always sought to extend the market in order to accumulate, her theory cannot distinguish between the original expansion of trade and money economies at the dawn of capitalism in Europe and its later imperialist expansion... mercantile capital was necessary for the original accumulation of capital but this is a qualitatively different phenomenon from the capitalist drive to accumulate once it is established as the dominant mode of production." (RP 6 p.18-19)

In this passage the CWO's virulence against ‘Luxemburgism' outdoes even Bukharin's sharp polemic. A number of points should be made before we proceed any further. First, Luxemburg never said that imperialist expansion was aimed ‘merely' at finding new markets: she clearly portrayed its planetary quest for cheap labour and raw materials, as the CWO themselves note on the same page of RP 6. Secondly, it is astonishing to present capitalism's need to "extend the market in order to accumulate" as a discovery of Luxemburg, when it is a fundamental position defended by Marx against Say and Ricardo, as we have already seen. Bukharin himself in no way denied that imperialism was looking for new markets; in fact he identifies this as one of the three motive forces behind imperialist expansion:

"We have laid bare three fundamental motives for the conquest policies of modern capitalist states: increased competition in the sales markets, in the markets of raw materials, and for the sphere of capital investment. These three roots of the policy of finance capital, however, represent in substance only three facets of the same phenomenon, namely of the conflict between the growth of productive forces on the one hand and the ‘national' limits of the production organisation on the other." (Imperialism and World Economy, chap 8, p.104)

Nevertheless, the charge remains: for Lenin, Bukharin and others the ‘export of capital' rather than of ‘commodities' distinguishes the imperialist phase of capital from previous phases. Does Luxemburg's theory ignore this distinction and thus imply that imperialism was a feature of capitalism from the beginning?

If we refer back to the passages by Luxemburg quoted in this text, particularly the long citation from Anti-critique, we can see that Luxemburg herself clearly distinguished between the phase of primitive accumulation and the imperialist phase, which is unquestionably presented as a definite stage in the world development of capital. Are these just empty words or do they correspond to the substance of Luxemburg's theory?

In fact there is no contradiction in Luxemburg's analysis here. Imperialism properly speaking begins after the 1870's when world capitalism attains a significant new configuration: the period of the constitution of national states in Europe and North America is over, and instead of having a situation where Britain is the ‘workshop of the world' we have several highly developed national capitalist ‘workshops' competing for domination of the world market - competing not only for each others' home markets but also for the colonial market. It is this situation which provokes the depression of the 1870's - the "seeds of capitalist decadence" precisely because the decline of the system is synonymous with the division of the world market between competing capitals - with the transformation of capital into a ‘closed system' in which the problem of realization becomes insoluble. But of course in the 1870's, the possibility of breaking out of the closed circle still existed, and this largely explains the desperate haste of imperialist expansion in this period.

It is true, as the CWO point out, that capital always sought colonial markets, but there is no mystery in this. Capitalists will always look for areas of profitable exploitation and easy selling even when the markets available ‘at home' have not been completely saturated. It would be absurd to expect capitalism to follow an even course of development - as if the early capitalists got together and said to themselves: ‘first we'll exhaust all the pre-capitalist sectors in Europe, then we'll expand into Asia, then Africa, etc'. Nevertheless behind the chaotic growth of capitalism, a definite pattern can be seen: the colonial plunder of early capitalism; the use of this plunder to accelerate the industrial revolution in the metropoles; then, on the basis of industrial capital, a new thrust into the colonial regions. To be sure, the first period of colonial expansion was not a response to overproduction at home, but corresponded to the necessities of primitive accumulation. We can only begin to talk about imperialism when colonial expansion is a response to the contradictions of fully developed capitalist production.

To this extent we can see the beginnings of imperialism when the commercial crises of the mid-19th century act as a spur to the expansion of British capital towards the colonies and semi-colonies. But as we have said, imperialism in the full sense of the term implies a competitive relationship between capitalist states; and it was when the metropolitan market had been decisively carved up by several capitalist giants that imperialist expansion becomes an unavoidable necessity for capital. It is this which explains the rapid change in British colonial policy in the latter part of the 19th century. Prior to the depression of the 1870's, to the sharpening of competition from the US and Germany, British capitalists were questioning whether the existing colonies were worth the expense of their upkeep and were reluctant to take on new colonies; now they were convinced that Britain had to maintain and extend its colonial policy.

The scramble for colonies at the-end of the 19th century wasn't the result of a sudden fit of madness on the part of the bourgeoisie, or a vainglorious search for national prestige, but a response to a fundamental contradiction in the accumulation cycle: the growing concentration of capital and the carving up of the market in the metropoles, simultaneously aggravating the falling rate of profit and the gap between productivity and solvable markets, i.e. the problem of realization.

The idea that the need to open up new markets was a determining element in imperialist expansion is, contrary to the CWO's claim in RP6 (p.19), not contradicted by the fact that the bulk of world trade in this period was conducted between the capitalist metropoles themselves. This phenomenon was noted by Luxemburg herself:

"...with the international development of capitalism, the capitalization of surplus value becomes ever more urgent and precarious, and the substratum of constant and variable capital becomes an ever-growing mass - both absolutely and in relation to the surplus value. Hence the contradictory phenomena that the old capitalist countries provide ever larger markets for, and become increasingly dependent upon, one another, yet on the other hand compete ever more ruthlessly for trade relations with non-capitalist countries." (Accumulation, chap 27, p.367).

The ‘external' market for global capital was like a breathing space in a prison that was growing more and more crowded. The more the breathing space shrank relative to the overcrowded population of the prison, the more desperately the prisoners fought over it.

Neither does the fact that this period saw a great increase in the export of capital mean that imperialist expansion had nothing to do with a markets problem. The export of capital to the colonial regions was necessary not only because it allowed capitalism to produce in areas where labour power was cheap, and hence raise the rate of profit. It also extended the world market:

a) because capital exports include the export of producer goods which are themselves commodities which must be sold.

b) because exporting capital - whether in the form of money capital for investment, or producer goods - served to extend the entire market for capitalist production by implanting it into new regions and by bringing more and more solvent buyers into its orbit. The most obvious example of this is the building of railways, which served to extend the sale of capitalist commodities to millions and millions of new buyers.

The ‘problem of the market' can help to explain one of the most striking characteristics of the way imperialism extended capitalist production across the world: the ‘creation' of underdevelopment. For what the imperialists wanted was a captive market - a market of buyers who wouldn't become competitors with the metropoles by becoming capitalist producers themselves. Hence the contradictory phenomenon whereby imperialism exported the capitalist mode of production and systematically destroyed pre-capitalist economic formations - while simultaneously holding back the development of native capital by ruthlessly plundering the colonial economies, subordinating their industrial development to the specific needs of the metropolitan economy, and bolstering up the most reactionary and submissive elements in the native ruling classes. This is why, contrary to Marx's expectations, capitalism did not create a mirror image of itself in the colonial regions. In the colonies and the semi-colonies there were to be no fully formed, independent national capitals with their own bourgeois revolutions and healthy industrial bases, but rather, stunted caricatures of the metropolitan capitals, weighed down by the decomposing remnants of the previous mode of production, industrialised in pockets to serve foreign interests, with bourgeoisies that were weak, born senile, both at the economic and at the political levels. Imperialism thus created underdevelopment and will never be able to abolish it; at the sane time it ensured that there could be no national bourgeois revolutions in the backward zones. And, it is to no small extent that these profound repercussions of imperialist development - repercussions which are still only too apparent today, as the ‘Third World' sinks into barbarism - have their origins in imperialism's attempt to use the colonies and semi-colonies to solve its markets problem.

2) According to Bukharin, Luxemburg's definition of imperialism means that imperialism ceases to exist when there's no remnant of a non-capitalist milieu to be fought over:

"...it follows from this definition that a fight for territories that have already become capitalist is not imperialist, which is utterly wrong... it follows from the same definition that a fight for already ‘occupied' territories is not imperialism either. Again, this factor of the definition is utterly wrong... Here is a striking example to illuminate the untenability of Luxemburg's conception of imperialism. We mean the occupation of the Ruhr territory by the French (1923-24). From Rosa Luxemburg's point of view this is not imperialism since (1) the ‘remains' are missing, (2) there is no non-capitalist milieu, and (3) the Ruhr territory already had an imperialist owner before the occupation." (Imperialism and the Accumulation of Capital, chap 4, p.253).

This argument is reiterated in the naïve question posed by the CWO at the recent international conference in Paris, "Where are the markets pre-capitalist or otherwise, in the war Ethiopia and Somalia fought over the Ogaden Desert?" Such questions betray an extremely shallow understanding of what Luxemburg was saying, as well as a regrettable tendency to see imperialism not as "an innately international condition, an indivisible whole" but as "the creation of any one or any group of states": in other words, it looks at the problem from the fragmented point of view of individual national capitals.

If Bukharin had troubled to quote from more than the first sentence of the passage from Luxemburg's Accumulation, which we have cited in full, he would have shown that, for Luxemburg, the growing exhaustion of the non-capitalist milieu meant not the end of imperialism, but the intensification of imperialist antagonisms between the capitalist states themselves. This is what Luxemburg meant when she wrote that "imperialism brings catastrophe as a mode of existence back from the periphery of capitalist development to its point of departure" (Anti-critique). In the final phase of imperialism, capital is plunged into a horrendous series of wars where each capital or bloc of capitals, unable to expand ‘peacefully' into new areas, is forced to seize the markets and territories of its rivals. War becomes the mode of survival of the whole system.

Of course Luxemburg expected proletarian revolution to put an end to capitalism well before the non-capitalist milieu had shrunk to the insignificant factor that it is today. The explanation of how decadent capitalism has prolonged its existence in the virtual absence of this milieu belongs to another text. But as long as we continue to see imperialism as "a product of a particular stage of ripeness in the world development of capital, an innately international condition, an indivisible whole", we can still see the relevance of Luxemburg's definition. It only needs to be modified to the extent that today, imperialist policies of conquest and domination are brought about by the almost complete disappearance of an external market, rather than being a direct struggle for pre-capitalist remnants. The important thing to emphasise is that it is a global change in the evolution of world capital - the exhaustion of the external market - which compels each particular segment of capital to behave in an imperialist manner.

To return to Bukharin's objections: it is pointless to look for ‘non-capitalist milieus' in every imperialist conflict, because it's capital as a whole, global capital, which requires an external market to expand into. For the individual capitalist, capitalists and workers offer a perfectly good market for his goods; similarly , for an individual national capita), a rival capitalist nation can be used to absorb its surplus value. Not every market fought over by imperialist states ever was or is a pre-capitalist one, and this is less and less so the more these markets become incorporated into world capital. Neither is every inter-imperialist struggle a struggle directly for markets at all. In today's situation, the global rivalry between the US and Russia is conditioned by the impossibility of progressively expanding the world market. But many - perhaps most - of the specific aspects of the foreign policies of the US and Russia are aimed at securing strategic/military advantages over the other bloc. For example: Israel isn't much of a market for the US, or Cuba for Russia. The outposts are kept afloat mainly for their strategic/political value, at considerable expense to their backers. On a smaller scale; Vietnam's pillaging of Cambodia's rice fields is just that: pillage. Cambodia hardly constitutes a ‘market' for Vietnamese industry. But Vietnam is forced to pillage Cambodia's rice fields because its industrial stagnation leaved its agricultural sector incapable of producing sufficient food for the Vietnamese population. And its industrial stagnation is brought about by the fact that the world market can't expand, is already divided up, and won't permit any newcomers. Once again, it's only possible to make sense of these questions by beginning from a global standpoint.

POLITICAL CONCLUSIONS: IMPERIALISM AND THE IMPOSSIBILITY OF NATIONAL WARS

The practical issues in the theoretical debate on imperialism have always been centred round one question: does the epoch of imperialism make revolutionary national wars more likely, as Lenin argued, or does it make them impossible, as Luxemburg insisted? For us, history has indisputably verified Luxemburg's assertion that:

"The general tendency of present day capitalist policies determine the policies of the individual states as their supreme is blindly operating law, just as the laws of economic competition determine the conditions under which the individual manufacturer shall produce." and that consequently, "In the era of the unleashing of this imperialism, national wars are no longer possible. ‘National interests serve only as the pretext for putting the labouring masses of the people under the domination of their mortal class enemy, imperialism." (Junius Pamphlet)

The first citation has the following concrete applications in this epoch, both of which resoundingly confirm the second one.

a) Every nation, every aspiring bourgeoisie, is forced to align itself with one of the dominant imperialist blocs, and thus to conform to and carry out the needs of world imperialism.. Again in Luxemburg's words:

"The small nations, the ruling classes of which are the accomplices of their partners in the big states, constitute only the pawns on the imperialist chessboard of the great powers, and are used by them, just like their own working masses, in wartime, as instruments, to be sacrificed to capitalist interests after the war." (Junius Pamphlet)

Contrary to Lenin's hope that imperialism would be weakened by the revolt of the ‘oppressed nations', all national struggles in this epoch have been transformed into imperialist wars by the irreversible domination of the great powers; as Lenin himself recognised, imperialism means that the whole world is divided up by the great capitalist states, "So that in the future a re-division is possible, i.e. territories can only pass from one ‘owner' to another, instead of passing as ownerless territories to an ‘owner'." (Imperialism, Highest Stage...) The experience of the last sixty years has shown that what Lenin applied to ‘territories' can be applied to all nations as well. None can escape the stranglehold of imperialism. This is patently obvious today when the world has, since 1945, been divided into two permanently constituted imperialist blocs. As the crisis deepens and the blocs reinforce themselves, it becomes clear that even capitalist giants like Japan and China must humbly submit to the dictates of their US overlord. In such a situation, how can there be any illusions about national independence for the chronically weak countries of the ex-colonial regions?

b) Every nation[5] is compelled to act in an imperialist manner towards its rivals. Even while subordinating themselves to a dominant bloc, each nation is forced to try to subject other, smaller nations to its hegemony. Luxemburg noted this phenomenon during World War 1, in relation to Serbia:

"Serbia is formally engaged in a national war of defence. But its monarchy and its ruling class are filled with expansionist desires as are the ruling classes in all modern states... Thus Serbia is today reaching out towards the Adriatic Coast where it is fighting out a real imperialist conflict with Italy on the backs of the Albanians." (Junius Pamphlet)

The asphyxiated state of the world market makes decadence the epoch of war of each against all. Far from being able to escape this reality, small nations are forced to adapt themselves to it completely. The extreme militarization of the more backward capitals, the frequent outbreak of wars between local states in the underdeveloped regions, are chronic indicators of the fact that "no nation can hold aloof" from imperialist policies today.