World Revolution no.306, July/August 2007

- 3485 reads

Terrorism strengthens the capitalist state

- 2602 reads

Two Mercedes packed with petrol, gas cylinders and nails parked in London’s West End and ready to be detonated. A jeep with gas cylinders crashes into a terminal at Glasgow airport. The targets? Clubbers with no ambitions beyond having a good night out, and holiday makers looking forward to flying away for a glimpse of the sun. Whoever planned the attacks is fully in tune with the ways of modern warfare, which makes its offensive on concentrations of civilians, whether in Dresden, Hiroshima, Baghdad or the Tiger Tiger club. In disregarding the likelihood of retaliation they’ve also shown their contempt for the effects on Muslim or immigrant communities.

One of those who were arrested in connection with the failed bombings was said by a friend to be “very angry about the West”. But creating spectacular carnage in crowded places is every bit an expression of imperialist conflict and has nothing to do with the struggle against the system that gives rise to war. On the contrary, the whole ideology of jihadism takes real anger and discontent and channels thembrown into militarism, imperialist war and suicidal self-destruction. Politicians and the media rant about extreme political Islam being a threat to ‘our values’, when in fact the individual bomber and the state air force share the same goals and the same means of terror.

All change with Brown?

With the attempted London bombings coming within hours of Gordon Brown’s appointment of his first cabinet, there was a prime opportunity for the new government to show that it was committed to the reinforcement of the British state. In contrast to Blair’s familiar rush to introduce emergency legislation, Brown was praised by the likes of Liberty director Shami Chakrabarti, because “He has not played politics with the terror threat”.

In fact there is already planned legislation that will be introduced before the end of the year and will possibly include: an extension of the time available for detention from 28 to 90 days, the use of phone tap evidence, longer sentences for ‘terrorist’ offences, the power to seize passports and carry on interrogations after charging, among a number a number of other measures. No new measures have been instantly proposed partly because previous governments have been so enthusiastic in strengthening the legislative and technological aspects of their repressive arsenals. From the record number of CCTVs installed, to the reinforcement of the security forces, to the fact that, in law, almost anything can be interpreted as ‘glorifying’ terrorism, the state has a very wide range of powers at its disposal, while still selling the myth of British democracy and its inherent sense of ‘fair play’.

But it’s not wrong to notice a slightly different emphasis in Brown’s approach. It’s not just that the new Home Secretary is allowed to say a few words, but that no one in government will be using the expression ‘war on terror’, and it will focus on specific groups such as al Qaida rather than unidentified ‘Muslim extremists’, while trying to win the battle for ‘hearts and minds’. Brown said “security measures have to be increased” and people should be prepared to accept a greater police presence. But he also said there should be an ideological campaign, similar to that throughout the period of the Cold War, aimed at defeating Islamic fundamentalism and bringing everyone into line with the values of British democracy.

This is always a priority for the ruling class. The attempt to unite the population behind the needs of their exploiters is a constant for every government, whether of left or right. Since the advent of Brown there has already been some movement from those who had previously been reluctant to openly side with Blair. For example, full page advertisements appeared in many papers on 6 July from ‘Muslims United!’, in which you could read that “We are united with the rest of the country at this critical time and are determined to work together to avert any such attacks targeting our fellow citizens, property and country” before going on to “commend the government for its efforts to respond to this crisis calmly and proportionately”.

The idea that we should all be united in defence of ‘our country’ is at the core of nationalism and against any emerging understanding that we live in a society divided into classes with antagonistic interests. Whether that nationalism is expressed by Gordon Brown demanding more opportunities to hoist the Union flag and crying ‘British workers for British jobs’, or by Iraqi insurgents trying to drive out the foreign infidel for the benefit of a home-grown ruling class, or by car bombers bringing the war to Britain, it is always an ideology of the ruling class.

Loyal opposition

In the face of terrorist attacks the main parties of the bourgeoisie tend to adopt a united front. The latest, if failed, attacks have provided the perfect ammunition for the ruling class’s continual campaign to rally citizens to the state. In that sense, the main beneficiary of the recent attempted bombings is the British state.

However, there are some groups that appear to dissent from the consensus over terrorism. The Socialist Workers Party, for example, was not wrong to observe that “Brown repeated Tony Blair’s claim that bombs in Britain are not a product of the carnage in the Middle East” (Socialist Worker 7/7/7). There is indeed a connection, a link between two theatres in an imperialist war. But when leading SWP member and Stop the War Coalition convenor Lindsey German declared that “What Britain needs is not more terror laws but a change in foreign policy” she is promoting a serious illusion, the idea that capitalist governments can adopt a friendly or ‘ethical’ foreign policy. British imperialism pursues a foreign policy that is enforced with military weight and resources from every part of the state because that is what every capitalist state is forced to do in defence of its interests. And at home every state has to deploy every means not only against foreign threats but against the menace of the class struggle, the struggle of a working class which has no shared interests with its exploiters.

WR 7/7/7.

Recent and ongoing:

- Terrorism [1]

Postal strike: Solidarity means a common struggle

- 3408 reads

On Friday 13 July postal workers throughout Britain will be engaged in the second national strike against the Royal Mail’s derisory wage offer of 2.5% with strings. The first strike showed that the vast majority of postal workers are resolved to fight against the RM offer. Throughout the whole industry the strike was solid with a maximum number of workers on strike, contrary to RM’s initial claims. Workers showed scant regards for legal guidelines about numbers of pickets as scores of workers joined the picket line, in some cases reinforced by other public sector workers coming to show solidarity.

Next Friday’s strike will, in all likelihood be the same. But RM is counting on this willingness to fight fading over time, and there is a real danger of this strike being isolated and ground down. There are already signs of this happening. Royal Mail are adamant about sticking to their ‘plan’ for modernising the Post Office, and following the breakdown of the last round of negotiations it would seem that they are not moving an inch. This scotches the idea put forward by the CWU that strikes would bring RM to the negotiating table with a better offer, and RM has said that it is ready to deal with a long strike. The CWU have from the onset of this dispute refused to say exactly what the demands of the postal workers are. All they are doing is to oppose the 2.5% offered by RM. But we can get an idea of what the CWU really expects from the strike when we look at the statement by Dennis Kilagriff, CWU’s South Central Divisional Representative, published (without any criticism) in Socialist Worker of 7.7.07. “The CWU calls for:

* Royal Mail to enter meaningful talks with the union on resolving pay and major change, and to honour agreements that committed both parties to agree a joint approach on pay and modernisation.

* An urgent government review of the damaging impact of competition on Royal Mail to date, in line with Labour’s manifesto commitment.

*An immediate change to Postcomm’s competition rules and a fairer pricing and access regime that gives Royal Mail the revenues it needs to support the universal postal service and post office network.”

In short: all the CWU are calling for is for Royal Mail to have a bigger slice of the pie, calling for the rules of capitalist competition to be rewritten in its favour. The main concern of the CWU is therefore not the class interests of the workers but the efficiency of their boss – the Post Office. In particular, the CWU are not against ‘modernisation’ which will mean automatic redundancies - all they are doing is haggling over the numbers. The fact that postal workers are striking because they are effectively facing pay-cuts and redundancies does not come into the equation.

The postal workers have a massive will to fight but they are not in control of this struggle – its demands or its methods. Workers who have time and time again thrown away the union rule-book and come out on strike after holding on the spot mass meetings understandably hesitate about taking things into their hands when it comes to a large national strike. This hesitation is giving a free hand for the CWU to run the strike – and to ‘sell it out’ at the end.

Against the union’s attempts to make ‘negotiation’ the goal of the struggle, postal workers need to find the real sources of their strength:

- organising their own struggle through mass meetings open to all workers. Mass meetings need to decide when to strike, how to strike and what demands to raise

- seeking the active support and solidarity of other workers. Immediately by linking up directly with the Crown Post Office workers who are facing the same rotten deal. But other workers in the public sector are facing exactly the same attacks. In fact the postal workers are being set up as a test case in order that these attacks can go forward. No sector of workers can gain from struggling in isolation. Real solidarity means waging a common struggle.

The wider the resistance, the less the chance of the ruling class picking us off one by one.

WR 7/07/07.

Geographical:

- Britain [2]

Recent and ongoing:

- Class struggle [3]

Brown premiership: Same attacks in new wrapping

- 2549 reads

As he stood outside the door of Number 10 on the day he became Prime Minister, Gordon Brown declared his commitment to change: "Change in our NHS, change in our schools, change with affordable housing, change to build trust in government, change to extend and protect the British way of life." He declared he had "listened and...learnt from the British people" and pledged to lead "a new government with new priorities" and "to reach out beyond narrow party interest." In his new government he brought in new ministers and advisers, some of who were critics of the war in Iraq, others from the Liberal Democrats and others again from outside party politics altogether. He was welcomed by many leader writers and commentators and within a few days Labour moved ahead in the polls for the first time since Cameron was elected Tory leader. Brown's response to the attempted bombings in London and Glasgow underscored the change. Where Blair had thrust himself into the limelight, Brown allowed the new Home Secretary, Jacqui Smith, to take the lead. Where Blair echoed Bush's rhetoric about the ‘war on terror', Brown banned the use of the term and instead talked about ‘winning hearts and minds' in our ‘communities'. He was rewarded by the greater willingness of the official Muslim organisations to denounce the latest attacks and call for cooperation with the police.

Is this all just window dressing? In one sense, yes, since there will be no change of substance: the working class will still be exploited; foreign policy will still amount to war and imperialist manoeuvres; the government will still defend the interests of the ruling class. In another sense, no: the ruling class does need to make changes to maintain its control over society and to keep exploiting the working class. This is one of the features of bourgeois politics. At every election we are promised a new start, a fresh beginning, a change from the worn out policies and people of yesterday. This was true of Labour in 1945, the Tories in 1979 and New Labour in 1997. Parties transform themselves as Labour did under Blair and as the Tories are trying to do under Cameron. The idea of real change and real alternatives, where the masses make the choice, is fundamental to the working of a political system that actually defends the interests of a minority. At the same time real change does happen, but it is change that secures the position of the ruling class. Thus in 1945 Labour was swept to power to mark the change from war to peace and pledged to make good on all the promises of a better tomorrow that had been used to get the working class to accept the sacrifices of war. The ruling class still remembered what happened after the First World War in Russia and Germany. In 1979 the Tories under Thatcher replaced Labour in order to accelerate the economic attacks that were necessary to keep British capitalism going, leaving Labour free to mop up the anger amongst working people that resulted. In 1997 this arrangement was no longer necessary as the collapse of the eastern bloc had led to a retreat in the class struggle, so New Labour could come to power on the back of the hatred of the Tories while continuing the same policies. They were also better placed to defend Britain's imperialist interests in the post cold-war period that required a path to be found between Europe and the US.

Renewal in power

So why the need for change now? Blair had said he would stay until the end of the third term, now he has been pushed from office three years early. In the management of the economy and in containing the working class he has done what was asked of him, but there were two reasons why he had to go. Firstly, in foreign policy he moved too close to the US, tied Britain up in two wars that seem to have no end and reduced Britain's power and position in the world further than ever. "The full extent of the weakening of British imperialism was exposed by the conflict in the Lebanon...the fundamental significance...was that it confronted it with the reality of its status as an imperialist power and marked another stage in the historic decline of British imperialism" (‘Resolution on the British situation [4] ', WR 302).

The second reason was that he undermined the internal life of the British ruling class by replacing its traditional structures and ways of working with his own faction. This is a feature of the current period of capitalism where the absence of any sense of perspective for the ruling class has led to a loss of discipline that in some countries has threatened its capacity to rule. This is not the case in Britain, but the very fact that it has been affected by this tendency is a serious danger that the British ruling class knows it has to combat.

Initially pressure was put on Blair to mend his ways, but when it became clear that this was not going to happen the ‘loans for peerages' scandal was stepped up with the arrest of some of his close allies and the interviewing of Blair himself by the police. After the attempted coup by Brown's supporters last September, Blair was forced to announce he would leave within the year. The ruling class accepted this delay partly because he had served them well in many ways, but more because it was important to engineer an ‘orderly handover' to avoid any sense of crisis or panic. Three weeks before he left office Blair was interviewed by the police for a third time just to make sure he had got the message.

But, if this is the case, why were the Tories not put into power? There are two reasons. In the first place, for all the changes that Cameron has made, which have been reflected in the Tories' rise in the polls, they are not ready for office yet, as the recent gaffes over policy suggest (e.g. divisions over grammar schools). The stage-managed defection of Tory MP Quentin Davies on the eve of Brown's assumption of power harshly underlined this. In the second place, New Labour has served the ruling class well, so there is no real need to bring the Tories in now. It is far better for the ruling class to keep its powder dry now in case the situation is quite different in a couple of years

Changes to strengthen the ruling class

In his first actions Brown signalled that he would address the concerns of the ruling class, that here at least there would be change. He stated that there will be no sofa politics under his leadership, overturned Blair's ruling that allowed Labour appointed officials to give orders to civil servants, held three cabinet meetings in his first week and declared his intention to return to the tradition of making major announcements to parliament rather than the press. In his first speech Brown informed the House of Commons that he would end or modify the executive's power to make decisions without recourse to parliament and suggested that this might include the power to declare war.

The shift in foreign policy was announced by appointing David Milliband as Foreign Secretary, by bringing in Shirley Williams as an advisor and Sir Mark Mallach Brown, a former deputy secretary-general of the UN, as minister for Africa, Asia and the UN, and offering a place to Paddy Ashdown who is known to be pro-European. Milliband criticised Blair's position over the war in the Lebanon last year, Williams opposed the war in Iraq and Mallach Brown has been an open critic of Bush and Blair. This last appointment has already been criticised by John Bolton, the former US ambassador to the UN as "inauspicious" while being hailed as "a statement of independence" by a former head of the United Nations Association (Guardian 29/6/07). Brown himself has been careful to avoid being contaminated by Blair's military adventures, only beginning to travel abroad during Blair's final days and even then keeping the focus on such ‘good news' stories as his efforts to relieve poverty in Africa.

The limits of change

However, while the bourgeoisie may be able to nuance its foreign policy and rein back some of the manifestations of the disorder within their own class, they cannot overcome the fundamental problems that confront them. What Blair was punished for cannot be solved by a simple act of will.

Britain's imperialist policy is a consequence of its history and its current position. Since 1989 this has meant steering a path between the US and Europe. However, it has been unable to play one off against the other so Blair gambled on moving closer to US and lost. Even though Blair has gone it is not possible to put the clock back. Britain's weakened power has been exposed and there is no basis yet for overcoming the divisions this produced in the bourgeoisie. Certainly the ruling class will try to respond to this situation and there may be some shifts in policy ahead of us but there is no way back to Britain's former standing.

Similarly, the pressures that push the various clans in the ruling class to pursue their factional interests may be ameliorated but they cannot be eradicated. They arise from the very foundation of capitalist society in its phase of decomposition, from the absence of any sense of a future beyond mere survival and looking after number one. One example of this was the way that the attempt to bring Blair back into line used methods that themselves fuelled the loss of discipline: "Thus, during the Butler inquiry the security service set up a website and published confidential documents that contradicted the government's claims about Iraq and weapons of mass destruction" (‘Resolution on the British situation', op cit).

Even in the areas where Blair was praised there are serious difficulties. The economy, the basis of Brown's own claim to success, has only grown at the cost of the working class. The latest report from the IMF in March this year showed that personal spending remains the main factor in the growth of the economy and that, as a consequence personal debt has continued to rise, and that the current account is projected to remain in deficit over the next few years. The housing market, which has financed much of the increased personal spending, has begun to accelerate again, increasing the possibility of a sharp readjustment that could have a severe impact on growth.

Finally, for all of its ability to control the class struggle, the necessity to continue to make the working class pay for the economy through debt, low pay and long hours only increases the possibility of anger turning to resistance and of defence turning to attack. This at last would be a change that benefits the working class.

North 4/7/7.

Geographical:

- Britain [2]

General and theoretical questions:

- Economic crisis [5]

Gang culture: symptom of a rotting social system

- 2915 reads

Gang violence has always been a feature of class society, but with onset of decomposition, the final phase of the decadence of capitalism, it has reached new heights of irrational barbarity. The recent epidemic of violence amongst young people in Britain is just another depressing example of this phenomenon. Over a period of eight days in June this year eight young people, all under the age of 25, were murdered in London. All victims of London’s ‘gang culture’. This trend, which is already a part of life in the US and many countries on the periphery of capitalism, is being repeated in cities across the country.

These teenagers were not stabbed and shot in botched robberies. This outbreak of violence cannot be explained in the same way as the violence that occurred, say in the Eighteenth Century, when London was arguably more dangerous than it is today. Today’s gangs, teenagers themselves, often kill to defend their neighborhoods and their honour. ‘Respect’ is everything. Just looking at someone in the wrong way can result in a beating. This is the ‘rationale’ behind many of these crimes – or rather, the irrationale.

Whether from the left or the right, the bourgeoisie, especially in the guise of self-appointed ‘community leaders’, has used these events to promote their own solutions to the problem. Given the state of the prison system they can’t just ‘lock em up’, so the advertised solutions usually involve increased funding for specific ‘communities’ or pet ‘community projects’ or ‘police initiatives’. But teaching teenagers about citizenship, providing more youth clubs and pretending that every teenager can make it big in the music industry will not stop, or help us understand, this violence.

Teenagers may be brutalised by the gang mentality, and its negative impulses can be reinforced by the influence of cultural expressions like grime and gangsta rap, but none of this exists in a vacuum. Behind all this brutalisation there lies a greater social force. Whether in Brixton or Buenos Aires, from birth we are forced to deal with the logic imposed by capitalism: competition and the pursuit of profit at any cost. In the period of decomposition, with the bourgeoisie unable to provide any sort of perspective for the future, this logic is taken to its natural conclusion: ‘every man for himself’, ‘every nation for itself’. Young people today grow up in a world where this ideology infects their every move. Faced with a grim present and an uncertain future, defending your family, your street and your estate appear to some teenagers to be the only action worth taking. The ideology of ‘reppin your end’ ultimately obeys the same logic as that of imperialist powers defending their spheres of influence, and the insane violence of gun and knife ‘culture’ is only the reflection of a world system permanently at war.

Of course, there is a solution to this problem that the bourgeoisie won’t mention. This solution was offered by young people in France last year in their struggle against the CPE. Through their use of general assemblies and collective action they were able to win a partial victory against the French bourgeoisie. Rather than being dragged into pointless violent confrontations, these young people brought disaffected youth across France together to fight the bosses’ attacks. Young people in Britain and across the world need to do the same. Stop fighting each other and unite to fight the system that turns you into atomised individuals.

Williams, 5/4/7.

Geographical:

- Britain [2]

Workers respond to ANC attack on wages

- 2666 reads

In June a four week strike in South Africa involving between 600,000 and a million workers closed most schools, reduced hospitals to a skeleton run by army medics and had an impact on much public transport and many offices. It clearly demonstrated which side the ANC government was on. While it was definitely the biggest strike since the end of apartheid in 1994, the COSATU unions’ insistence that it was a “historic turning point in the lives of public-sector workers” and that “This combination of unity and militancy means that never again will the employer dare to treat us with the callous indifference they have displayed in the past and during this dispute, until they were forced to compromise when confronted by the militancy and determination of their workforce” were exaggerations that hid the real significance of the strike.

Unions can’t be both friend and foe

In late May, a week before the strike started, there were demonstrations in towns and cities across South Africa, demanding an increased offer from the government in the deadlocked talks between government and unions.

The government initially offered the public sector a 6% wage increase while COSATU asked for 12%. COSATU went down to 9% and then 8%, before accepting 7.5%. Two weeks into the strike COSATU said that 7.25% was a completely unacceptable compromise, taking another two weeks to find the extra quarter of a per cent a ‘historic compromise’.

It’s not that COSATU is a weak or treacherous union; it’s actually a partner in the South African government! So every remark they made during and before the strike showed them as either explicitly an ally of the state employer or pretending to be a friend of the working class. The same goes for the South African Communist Party (SACP).

For example, troops were deployed against pickets on a number of occasions, using rubber bullets and tear gas. Pickets were denounced by the government as ‘violent’ and examples of ‘intimidation’, The action of police and troops were justified because of, in the words of Thabo Mbeki, “the unions’ message of selfish own interest”. The head of the police is SACP national chairperson Charles Nqakula.

Or again, when the government started sacking nurses who were on strike, public services minister Geraldine Fraser-Moleketi said that those who didn’t return to work were “being sacked in the interests of the patients and the country”. Fraser-Moleketi is one of three SACP members in the cabinet.

At one point the unions threatened a ‘solidarity strike’ which would have involved the crucial mining and manufacturing sector. Even this nominal action, involving ‘sympathy’ rather than extension to other sectors of workers, appears to have come to nothing. Similarly, the three unions at the national power utility Eskom, employing 31,000 workers, at one point said that a strike that could cause massive power cuts was imminent. It was planned for 4 July … a week after the public sector strike had been called off. It was then called off itself. Unions have given notice to 150 employers that workers in the metal and engineering industry will strike from 9 July. How long this strike will be depends on how union/employer ‘negotiations’ proceed.

Watch out for the left

Living and working conditions in South Africa have been declining over a long period for the vast majority of the population. Life expectancy, literacy, access to improved sanitation have all been declining, while South Africa now has 5.5 million HIV/AIDs patients, the highest number in the world, and every day there are 50 murders and 150 women are raped.

Archbishop Desmond Tutu, in an interview in the Financial Times (29/6/7) said that most people “are languishing in the wilderness” as he criticised the slow pace of wealth redistribution since the end of apartheid. “I’m really very surprised by the remarkable patience of people” Tutu said, adding that most of the people living in shacks under white rule were still doing so today. He said it was hard “to explain why they don’t say to hell with Tutu, Mandela and the rest and go on the rampage.”

One of the reasons that people have not gone ‘on the rampage’ is because they still have illusions in the unions, the ANC and capitalist democracy.

A Reuters report (28/6/7) said that “Unions accuse President Thabo Mbeki of abandoning the poor through his pro-business policies” and that the strike “focused attention on growing labour discontent over his strategy, which has helped turn South Africa into an economic powerhouse but failed to conquer widespread poverty and high unemployment left by apartheid.” A statement by a COSATU branch declared that “This crop of politicians have shown themselves to be unfit to lead our government in the interest of the poor. The ANC needs to replace them before it is contaminated with the greed that drives many public officials”.

But it’s not because of greed or particular economic policies that the ANC/SACP/COSATU government attacks the conditions of life of workers and other non-exploiting strata in South Africa. A capitalist government can’t be anything except ‘pro-business’ and therefore anti-working class. The only ‘liberation’ that happened in 1994 was for a small number of black political activists to take a more prominent position in the political apparatus of the ruling class. The elections that have occurred since have reinforced the idea that something fundamental has changed in South African society with the advent of a wider democracy. Socialist Worker (9/6/7) reported a worker on a march in Pretoria as saying “We thought the government would feel for us workers because we put them into power, but it’s like they have forgotten about us.” This kind of illusion is constantly being fed by the unions and leftists, who are happy to talk about the ANC’s capitulations to neo-liberalism but never to openly brand it as part of the class enemy.

Prospects for future struggle

In South Africa some commentators have seen the recent strike as a sign that the unions are going to play a more independent role and this will encourage workers to take future actions. In reality it is because of the growing discontent in the working class that unions try to distance themselves from the government. In Socialist Worker (23/6/7) there is the suggestion that the “mood is opening the door to a rebirth of self-activity during strikes.” It’s not clear exactly what is meant by this (written by Claire Ceruti of South Africa’s Keep Left organisation), but all the advocates of union action will be standing against the emergence of workers’ self-activity. Autonomous struggle can only mean that workers have taken charge of their struggle and have control of the direction it takes.

In many ways the most significant aspect of the recent struggles is their location. South African capitalism is the strongest in the continent and has the longest history as an industrialised country. And the history of the workers’ movement goes back into the 19th century.

The recent strike, although significant, is by no means unique in the period since 1994. In August 2005, 100,000 gold miners were on strike over pay. In September 2004 there was the biggest one day strike in South African history, involving either 800,000 workers or 250,000, depending if you believe unions or government. Teachers were particularly angry as they had had no pay review since 1996. In July 2001 there was a wave of strikes in the mining and power industries. In August 2001 there was a three week strike involving 20,000 workers in the car industry. In May 2000 strikes in the mining industry extended into the public sector. In the summer of 1999 there was a wave of strikes involving post office workers, gold miners and public sector workers including teachers, health care workers and others (see WR 227 ‘Workers strike against ANC austerity [6] ’ on our website). Implicitly all these struggles lead workers to come up against the ANC and the South African state. But the working class is only beginning to be aware of the nature of its enemy and the global significance of its struggles. This only emphasises the need for the development of a real revolutionary current in South Africa, capable of denouncing the traps laid down by the bourgeoisie, and of providing a clear orientation for future struggles.

Car 3/7/7.

Geographical:

- South Africa [7]

Tony Blair: Warmonger turned peacemaker?

- 3166 reads

Can Tony Blair follow the achievement of ‘peace' in Northern Ireland with peace in the Middle East? His retirement as PM and appointment as Middle East envoy for the ‘quartet' of the US, Russia, the EU and the UN, has been accompanied by this idea. Spin, pure spin!

First of all, there is no international community of the great and the good ready to stand as honest brokers for peace, only various imperialist powers out to defend their national interests in the area. The US has been an ally of Israel from way back in the period of the cold war, when the western imperialist bloc was confronted by the Russia imperialist bloc, with the latter using the PLO to harass their rivals in the Middle East. So the collapse of the Russian bloc brought about an important change in the balance of power in the region. The EU and UN both contain various nations with conflicting interests and alliances, but that does not mean they can stand for peace, only that they become an arena for conflicts to be played out diplomatically without for one moment ending the fighting on the ground. For example, in the EU, Britain took the opposite line to France and Germany on the invasion of Iraq in 2003; and in the 1990s Germany backed Croatia and Britain and France backed Serbia in the break up of Yugoslavia.

Secondly, Blair is not seen as any kind of neutral peace-maker. He is liked by Israel, because he is seen as being on their side, and distrusted by Palestinians for the same reason. His refusal to call for a ceasefire last year when Israel invaded Lebanon last year, and his role in the Iraq war, are reason enough for this.

In these aspects we can see a certain similarity with ‘peace-making' in Northern Ireland. The British government, under Blair or anyone else, is not a neutral observer, but defends British interests against the claims for Irish unity for instance. At the moment there is no power with a realistic immediate interest in backing violence at present - for instance as the USA did to punish Britain for taking a more independent foreign policy line - but the underlying conflicts have not gone away (see ‘Ireland: power sharing will not end imperialist conflicts' in WR 303 and ICC website).

Finally, the job of Middle East envoy is very limited and Blair's predecessor, James Wolfensohn, former President of the World bank, resigned from the post in frustration as no progress could be made. This is hardly surprising when the ‘quartet' is made up of powers with conflicting imperialist interests in the region. The brief includes Palestinian governance, economics and security. Nothing about the conflict between Israel and Palestine, so even his official mandate does not include ‘peace-making'.

Alex, 7/7/07

Geographical:

- Palestine [8]

General and theoretical questions:

- Imperialism [9]

Palestine: imperialist rivalries behind the Hamas/Fatah conflict

- 3436 reads

While Tony Blair lends his smile to the job of envoy, the situation in the Middle East has become increasingly complicated with the divisions between Hamas and Fatah in Palestine. Fighting between them has paused since Hamas took control of Gaza and Fatah consolidated in the West Bank. Palestine is now divided politically as well as geographically.

Gaza remains blockaded by Israel, resulting in the closure of 75% of its factories. Cross border fighting continues, with rocket attacks on Israel and military responses from the latter. At the time of writing we are hearing that there has been another Israeli raid on Gaza. By contrast, the government of Mahmoud Abbas, which controls the West Bank, has been rewarded by Israel for replacing the Hamas prime minister. Palestinian duties collected by Israel have now been released, and this has allowed the payment of Palestinian Authority employees for the first time in 16 months. Hamas supporters are not included. Abbas and Fatah are being encouraged, subsidised – and armed – as the alternative to Hamas that the ‘west’ can rely on in Palestine. The prospects of a two-state solution to the Israeli/Palestinian conflict could hardly look more absurd when the Palestinian would-be state is so divided.

Hamas is hoping that the kudos it has gained from the release of BBC journalist Alan Johnston will improve its position diplomatically. It has, after all shown that it has control of Gaza and is a force for ‘law and order’ against random kidnappers – as well as winning last year’s Palestinian election. Enemies of Hamas will point to many reasons why it should still be seen as a terrorist organisation. But yesterday’s terrorist is often today’s statesman and the real reason for unease about Hamas lies in the wider conflicts in the Middle East. Hamas is backed by Iran, and therefore by the ‘axis of evil’. Iran is, of course, run by a repressive theocracy and it is trying to develop nuclear weapons. But the US and Britain have backed many repressive regimes and in fact supported Saddam Hussein in the 1980s, when they used his regime to weaken Iran in a ten year war. Their real objection to Iran is that it is has the potential to rival Israel as the dominant regional power in the Middle East, and it is already causing problems for the USA and Britain in their occupation of Iraq through backing Shia gangs like the Mahdi Army of Al Sadr. The Israeli invasion of Southern Lebanon last summer was aimed against another Iranian pawn, Hezbollah, and had the tacit support of the USA. The Blair government backed it by refusing to call for a ceasefire.

Iran has been increasing its influence very effectively through aid to Hezbollah and Hamas. However, the main stimulus to its rise came from the weakening of the USA. Although still the world’s only superpower, with massive military advantages over any other country, or even over any other group of countries, it has seen its position gradually weaken. Getting bogged down in Iraq has dramatically worsened this tendency. The US military is now too stretched to contemplate another war on the same scale. Not only that, by effectively knocking Iraq out of the equation it has freed Iran from a major rival and fed its ambitions to rival or even supplant Israel as the most important regional power. Hence the great enmity between them: Iran’s bloodcurdling threats against Israel, and the latter’s attacks on Iran’s pawns in Lebanon and Gaza. So the invasion of Iraq has not only created appalling chaos there, but is greatly intensifying imperialist tensions throughout the region: not only in Israel, Palestine, and Lebanon, but also in Afghanistan where it has stimulated Taliban activity, in Pakistan where the army is involved in more and more clashes with Islamists and in Turkey which is threatening to make a major incursion into Northern Iraq to crush the Kurdish separatists (see ICC Online, ‘Problems of Decadent Capitalism in Turkey’).

Caught in the middle of these imperialist conflicts the populations of the Middle East, in Gaza, Israel and Lebanon as well as in Iraq and Afghanistan, can only expect a worsening of their situation, more raids, more bombs of the aerial or suicide variety. Neither the ‘Road Map’ nor the newly appointed ‘Middle East envoy’ offers any alternative. The only hope lies in the development of the struggle of the working class internationally. This is the only way workers in the ‘west’ can show their solidarity, by defending their own interests against the demands of the national interest. Class struggle is also developing in the Middle East in spite of permanent war and the incessant demands for national unity (see ‘Egypt: germs of the mass strike [10] ’ in WR 304, ‘Middle East: despite war, class struggle continues [11] ’ in WR 302 and ‘Israel/Palestine the proletarian alternative [12] ’ in WR 300, and ICC Online).

Alex 7/7/07.

Geographical:

- Palestine [8]

The Kornilov Coup, August 1917: Military blocs or autonomous class struggle?

- 7062 reads

Continuing our series of articles commemorating the 90th anniversary of the Russian revolution, we are re-publishing an article that first appeared in World Revolution number 13, in August 1977.

Few events in the history of the Russian Revolution have been so falsified by the counter-revolution as the Bolsheviks' supposed ‘alliance' with Kerensky's Provisional Government against General Kornilov's insurrection of August 1917.

Kornilov was the commander-in-chief of the Russian Army's South-Western front. As such he was under the command of Kerensky's Provisional Government, the regime which was the product of the February Revolution. Under the growing threat of the Soviets and the Bolshevik Party, Kerensky and Kornilov conspired to forcibly overthrow the Soviets in August. Kornilov, however, decided that Kerensky's democratic government had vacillated too much in respect to the Soviets, and had therefore played itself out. As a result Kornilov revised his plans and aimed to overthrow Kerensky in the process of crushing the Soviets.

Purely out of an instinct for survival, yet unable to sense fully the fundamental threat to bourgeois order represented by the Soviets, Kerensky pleaded for their all-out support once he had discovered Kornilov's duplicity. The Provisional Government placed itself in practice at the mercy of the Soviets in Petrograd as a protection against Kornilov. The Soviets dissolved Kornilov's detachment from within in the space of four days. In doing so, the awareness of its own strength, gained by this mass movement of the Soviets against Kornilov's coup, provided the Russian working class with the assurance it needed to smash the Provisional Government itself a few weeks later in October.

Very soon, the Kerenskys of this world, and , when it came to it, the entire world bourgeoisie, were to understand the enormity of the error committed by Kerensky when he opposed Kornilov's coup. He provided the Soviets with the unique opportunity to gain the upper hand in the balance of class forces in Russia by means of their struggle against Kornilov. Never again would factions of the democratic bourgeoisie commit such a blunder in their struggle against the proletariat. That this situation presented itself in such a uniquely favourable manner to the proletariat was partly due to the period (capitalism had just entered its period of permanent crisis in 1914), and partly to the ignorance of the bourgeoisie as to the real danger represented by the armed proletariat. After all, with the exception of the localised case of the Paris Commune in 1871, the workers had never destroyed the bourgeois state before. October 1917 marks also the first time that the proletariat held power on a national scale in this period of capitalist decadence.

The extreme left-wing of capital, especially the Trotskyists, have falsified the tactics of Bolshevism during this episode. To some of them like the International Spartacist Tendency, the alleged ‘military support' that Bolshevism is supposed to have given Kerensky against Kornilov's reactionary insurrection' is the single most important ‘lesson' of the Russian Revolution. In its future road to what the Spartacists consider to be working class revolution, if only the proletariat learns how to ‘militarily' support a faction of its class enemy, its own success is assured. Failure to follow this ‘lesson', the proletariat is warned, must result in fascism and rightist repression. The proletariat must at all costs abandon its own class terrain, its own goals, and place itself at the disposal (momentarily of course) of its democratic, leftist executioners because it isn't ‘strong enough' at that point to overthrow them. This counter-revolutionary sophistry, this myth about the ‘alliance' of Bolshevism with Kerensky, is a complete distortion of what actually took place. In effect, this distortion has been the basis for a whole series of mystifications, which have helped defeat the proletariat in the last fifty years of its history.

The tactics of the ‘united front' formulated by the Comintern in 1920-21 under Bolshevik influence depart in many ways from the basic distortions of this experience. Trotsky's writings on Germany (in 1930-34) use the ‘lessons' of the Kornilov coup time and time again to justify his policy of the united front between the two supposed workers' parties in Germany at that time, the Social Democracy and the Stalinists, against Hitler. In Spain in 1936-38, Trotsky again relies on the same arguments to defend, albeit ‘critically', those twin bastions of the ‘counter-revolution': the Stalinists and the Republic, against Franco,

"The Stalin-Negrin government is a quasi-democratic obstacle on the road to socialism; but it is also an obstacle, not a very reliable or durable one, but an obstacle nonetheless, on the road to fascism" (Trotsky).

He went on to say that if the proletariat ‘aided' in the destruction of the Negrin government, it would only be serving the fascists by doing so. It was necessary instead, Trotsky argued, for the proletariat to "find a correct attitude" toward the "hybrid struggle" between the Republic and Franco "in order to transform it from within [!] into a struggle for the proletarian dictatorship." In 1939-45, the Trotskyists followed in the footsteps of their mentor to use the same ‘anti-fascist' logic contained in this mystification to rally ‘military support from within' to Allied imperialism for its war effort against the fascist imperialisms.

In other words, the experience of the Kornilov coup has been distorted in such a way as to allow the left of capital to gag the proletariat on innumerable occasions. Today, when the present resurgence of the world proletariat threatens the capitalist order once more, this mystification of the ‘lesser evil' has again come into its own. The events in Chile and Portugal in this decade are a tragic testimony to its effectiveness as a weapon in the bourgeoisie's political arsenal. It is vital, therefore, to examine critically what happened during Kornilov's coup. Did the Bolsheviks really give ‘military' or any other kind of support to Kerensky?

The fundamental issue which is at stake for the proletariat in its examination of this event is the following: can the working class carry out any sort of common action with factions of the bourgeoisie in this epoch of the decay of capitalism? Our answer is a definite NO! "Wherever the proletariat comes out independently the bourgeoisie ceases to be a revolutionary class", Lenin wrote (www.marxists.org/archive/lenin/works/1906/dec/20.htm [13].) If anything confirmed this forever for the proletariat, it was the experience of the Russian Revolution. In order to show how the proletariat did not subordinate its struggle to any alliance with bourgeois democracy, we should first examine in detail the conditions of that period.

Class consciousness and democracy in 1917

The suddenness of the first imperialist war which plunged capitalism into its permanent epoch of decay caused immense confusion in the camp of the proletariat. The sudden passage of the 2nd International to the camp of imperialism in 1914 did not mean that the proletariat abandoned many of the illusions produced in the previous period of reformist struggle. In Russia, these illusions came to the fore immediately after the February 1917 Revolution. To take one example - for years the majority of the Russian revolutionaries thought that Russia would have to pass through a bourgeois democratic stage prior to the socialist revolution. The downfall of Czarism and the eventual coming to power of Kerensky's Provisional Government made many people believe that the ‘bourgeois revolution' was actually taking place. Soviets, stronger and more generalised than those which appeared in 1905, developed side by side with this liberal regime, but many workers still conceived the Soviets to be merely organs of support for it.

The Bolsheviks' call for the establishment of a Constituent Assembly also expressed the very real hesitations and confusions in the workers' movement at that time as to what was on the historical agenda for the working class. That the bourgeois democratic stage could not solve any real problems for the workers, soldiers and peasants became more and more apparent as the Provisional Government continued the war effort begun by the Czar. Consequently, a deep radicalisation unfolded in Russia, especially in the proletariat, as it came to understand that Kerensky had to be stopped, and that only the Soviets could lead society out of capitalist barbarism. The ‘bourgeois democratic stage,' had not erased one bit Russia's imperialist nature, and in fact it only tied the Soviets to the war effort of Russia and the Entente imperialisms.

Lenin's April Theses illustrate in a remarkably clear way the early conviction of the proletariat of the need to overthrow the bourgeois democratic regime. But this sharper understanding within the proletariat, including its communist fractions, was blunted by many incorrect assumptions still carried over from the past struggles of the class before the war. Some of these centred on the conception that the Provisional Government initially represented an inevitable stage in the revolution, but that it now had to be exposed because it was ‘betraying' and trampling on the ideals of democracy through its participation in the imperialist war and by defending the most backward strata of Russian capitalism.

The Soviets' initial support for the Provisional Government symbolized this confusion concerning the nature of democracy. And this confusion was deeply rooted in the minds of the Russian proletariat as it emerged from years of absolutist rule.

The Bolsheviks could not help but reflect these ambivalent conceptions; it was, after all, a completely new situation for the proletariat as it faced up to the tasks of a new epoch in its historical struggle for communism. After expecting the downfall of Czarism for years, and the establishment of a bourgeois republic, the workers were confronting in the space of weeks and months the new reality of this period. That reality was the complete bankruptcy of bourgeois democracy, and the enormous possibility for proletarian revolution internationally represented by the appearance of the workers' councils in Russia.

In a period of revolutionary upsurge, confusions are transcended rapidly and need not be fatal in an immediate sense. The class was, in any case, moving in its autonomous terrain, unifying itself, creating and steeling its organs of struggle. The old Bolshevik slogan of the ‘democratic dictatorship of the proletariat and peasantry' was quickly superseded by the need to stress ‘All Power to the Soviets'.

At the same time, the polarisation of political parties became sharper, as they obeyed their true class nature. The final evolution of the Social Revolutionaries (SRs - a radical petty-bourgeois party based on the peasantry), and the Mensheviks, was reaching its consummation. Initially, these parties were at the helm of the Soviets, and indeed one could say that as long as they expressed the hesitations and confusions of the classes organized in the Soviets, these parties reflected the heterogeneity within the Soviet camp which by its very nature could only be a temporary phenomenon. By defending and propping up the Provisional Government, however, they more and more revealed which class forces they represented. But even here, their evolution was by no means final - the Left SRs were to support the October Revolution and even participate in the first Soviet government. Equally factions of the Mensheviks either joined Bolshevism prior to the revolution, or participated in the Soviets after October. Overall, the brief support these tendencies gave Soviet power expressed also the proximity of a period in which parties of the radical petty-bourgeoisie had played a progressive role in the evolution of capitalism.

When the Bolsheviks called the leaders of these parties ‘compromisers' or ‘conciliators' prior to October, they were addressing a true moment in the life and development of these organisations. At that time, the experience of the proletariat had not given the final verdict as to the class nature of petty-bourgeois ‘conciliation'. The workers still went on seeing these parties as hesitant expressions of ‘popular' and ‘democratic' aspirations in the population at large, different in kind to the proponents of rightist counter-revolution.

When Kornilov, expressing the impatience and wrath of the bourgeoisie at the vacillations of its ‘compromisers', attempted to crush the Soviets, the workers' and the soldiers' councils reacted as one, although for different reasons. The workers saw the coup as a direct threat to the workers' revolutionary goals; the soldiers saw Kornilov as the enemy of democracy, of peace and as the foe of agrarian reform. The coup was therefore confronted as a danger to the democratic and socialist revolutions. The Bolsheviks, in their mobilization against Kornilov undertook it, not only to defend the workers' councils and the Soviets in general, but as a way to expose such democratic illusions in the Provisional Government, illusions which still held sway in the context of the Russian population as a whole. It is not that the Bolsheviks catered to the democratic illusions of the soldiers and the peasantry for ‘tactical reasons', but that these illusions in democracy revealed the proximity of a bygone-era in the world, and these were lingering confusionsfrom which the Bolsheviks themselves had not escaped entirely. The experience of the proletariat had yet to show that the era of soviet power expressed the fundamental antagonism existing between the soviets and bourgeois democracy, including its most ‘radical' manifestations. The Bolsheviks realised, especially after October, that bourgeois democracy was nothing but a weapon wielded by totalitarian imperialism against the working class.

Indeed, bourgeois democracy was used to the hilt in Germany and Central Europe to mercilessly crush the proletariat. The final test of democracy came for the whole proletariat in those years of 1919-23, when everywhere elections, parliaments, referendums, etc, were used to smother the workers' councils, if not to defeat them in the streets.

The ‘lesser evil' in the Kornilov coup

Among the best accounts of this episode is Trotsky's, contained in his History of the Russian Revolution. We refer the reader to that for details of the event. What we want to raise here are the two most important questions regarding Kornilov's coup:

1. Did Kerensky's ‘resistance' to the coup express a fundamental affinity of bourgeois democracy with the needs of the proletariat during this epoch? In other words, do the Kerenskys of capital offer the class something which is basically better from what the Kornilovs, the Hitlers, the fascists, i.e. the right of capital, can offer?

2. Did the proletariat defend Kerensky during the coup?

To both these questions the leftists vociferously answer ‘Yes'! For us, the answer is ‘No'!

1. If the Kerenskys of this world - and that includes the unions and other capitalist gangs the Trotskyists call ‘workers parties' - offer something better to the proletariat than the right, the proletarian revolution reduces itself to playing not only the ‘seven keys in the musical scale' as Trotsky said, but an eternal symphony on the theme of the ‘lesser evil'. Given the conditions of capitalist political decomposition in the crisis, the bourgeoisie will always attempt to produce a left face in an effort to raise proletarian support for capital. This is not only to recruit proletarian cannon fodder to defeat other national capitals, but as a way to crush the proletariat mercilessly from within, and thus defeat the danger of proletarian revolution. The whole history of the proletariat over the last fifty years is a bloody proof of the role of capital's left-wing. From Ebert and Noske to Stalin, Mao and Carrillo, capital can always produce, up to the last minute of its existence, a suitable ‘lesser evil' to attempt to seduce the proletariat from its own struggle into a struggle for capital. On this issue, Lenin and Trotsky provided a profound and corrupting confusion when they dismissed the crimes of the ‘compromisers' as things the proletariat should not take so seriously, because in Lenin's words, "... for the good of the cause the proletariat will always support not only the vacillating petty-bourgeoisie but also the big bourgeoisie..." (‘On Slogans [14]') He objected to petty-bourgeois ‘moralising' which would deny proletarian support to the ‘compromisers' against the ‘counter-revolution'. What Lenin and Trotsky never did see clearly was that these ‘compromisers', like Kerensky and Social Democracy, were in fact becoming, if not already, the counter-revolution. They were not the ‘lackeys' of capitalism - they were an essential capitalist weapon to defeat the proletariat. In an optimistic passage in Left-Wing Communism, an Infantile Disorder describing the future of communism, Lenin mentions in passing that: "... the Russian Bolsheviks were defeated in July 1917; over 15,000 German communists were killed as a result of the wily provocation and cunning manoeuvres of Scheidemann ,and Noske, who were working hand in glove with the bourgeoisie and the monarchist generals..." He failed to see that the scales of comparison were absurd. The ‘defeat' of the July Days in Russia quickly turned into a strengthening of the proletariat. By the end of July the Bolsheviks had recovered their strong influence in the factories and workers' districts in Petrograd. But the German Revolution never recovered politically from its crushing defeat, represented by the loss of more than 15,000 of its best fighters, Luxemburg and Liebknecht included, in 1919. From Kerensky to Noske there had already been a fantastic progression in terms of capital's ability to learn lessons against the class. It is Noske, and later Stalinism, which express in a more finished form the incipient murderous logic of democrats such as Kerensky. It is they who took to completion the job Kerensky was too impotent to do in Russia in 1917. After October, the world bourgeoisie instinctively recognized the need to fuse their Kerenskys and Kornilovs into one. In Germany this abominable Frankenstein, this juggernaut which splintered the proletariat and left it lying in the dust, was the German Social Democracy, Noske's party. It was first out into large-scale action with the full backing of the unions and other section of the bourgeoisie in 1918-19. This was the logic of Social Democracy's support for the imperialist war in 1914. In Russia this evolution of the ‘compromisers' became final and evident during the Russian Civil War, when the Social Revolutionaries and Menshevism definitely passed to the side of the White Armies and capitalism.

For the proletariat, relentless opposition to all its executioners isn't a question of ‘morality' or ‘revenge'. It is a question of life and death, of survival against its class enemy, against the class which stands in the way of the communist revolution. All the sophistries of Trotsky in 1932, when he ‘warns' the workers of the imminent rise of Hitler, amount to apologies for the degeneration of the Comintern and those two organisers of German capital, the Social Democracy and the German Communist Party. In China in 1927, as in Spain, it was the Communist Party which openly participated in the demoralisation or in the crushing of the proletariat. Compared with these insidious products of the counterrevolution, Kerensky's actions were like child's play. Never again would such vacillating tendencies appear in the camp of the bourgeoisie.

Seen from hindsight, Kerensky's role in the Russian Revolution appears as an aborted first attempt of capital to deal with the meteoric rise of the workers' councils in the first victorious proletarian revolution of this century. Since then, capital has produced better executioners, such as Stalinism. They do not need to conspire with any Kornilovs to crush the proletariat - Stalinism can itself attempt to accomplish that task with its own police forces and with a bestial cynicism that would even have shocked Kerensky.

The left of capital, including its democratic wings, have proven in this century to be no less murderous than the extreme right. That the Trotskyists cannot see this is not a mistake, or another proof of their stupidity. Every reactionary cause mobilises the cadre that are necessary. Their arguments on the Kornilov question are but another confirmation that Trotskyism organically defends its class, the capitalist class.

2. The other issue which we will deal with is the myth that the Bolsheviks actually ‘supported' Kerensky against Kornilov. This is not a question of words. The Trotskyists have muddled the whole issue and just because the workers' Red Guards, the soldiers and sailors didn't arrest Kerensky during the coup, they claim that this was ‘military support'. But in order to ‘support' something there must be something there in the first place to support. All evidence shows that the main, if not all, the thrust of the resistance to the coup came from the soviets, not from the few detachments still loyal to Kerensky. Detachments it should be noted which were intensely demoralised. The workers were not interested in defending Kerensky and the Provisional Government. They correctly saw the coup as the attempt of the counter-revolution to crush the Soviets. Many years later Trotsky affirmed that the Bolsheviks had an ‘alliance' with the Kerensky troops fighting Kornilov (which troops in the vicinity of Petrograd weren't subordinated to the Soviets?). He even said that the Bolsheviks ‘accepted the official command' of Kerensky as long as they were not sufficiently strong to overthrow him (again a formal truism which in this context becomes a lie). Trotsky also asserted later that the Bolsheviks did not remain ‘neutral' between the camp of Kerensky and that of Kornilov; and that they fought ‘in the first camp' against the second. This is a flagrant lie, a sad aspect of Trotsky's own degeneration as a revolutionary. His literary acrobatics, written in the middle and late 30s, distort his own brilliant account of the episode in his History.

By insisting hysterically that workers should not ‘abstain' or be ‘neutral' during inter-bourgeois conflicts, the Trotskyists, following in their master's footsteps, terrorise the class in order to place it solidly behind the ‘first camp' of the bourgeoisie. But this never happened during Kornilov's coup. When the Soviets fought Kornilov, they were doing so from their own terrain, under the hegemony of the revolutionary proletariat. The proletariat was becoming convinced of the need for its own class dictatorship. This autonomous awareness was not blunted by the Soviets calling for the defence of ‘democracy', which reflected in that specific historic conjuncture the ideological weight of other, non-capitalist classes increasingly alienated from the bourgeoisie and Kerensky.

If the Bolsheviks showed certain confusions in their formulations on whether Kerensky should be overthrown then, these confusions stem not only from agitational expediency but from the immaturity of the proletariat in that period. They did not stem from any opportunist strategy. Only later were these ambiguities ‘theorised' and made into sacred laws for the whole workers' movement to follow, especially from 1920 onwards, when Soviet Russia was becoming more and more isolated from the world proletariat, and these pressures inevitably brought demoralisation and political capitulation to the bourgeoisie. The ‘lessons' of the Kornilov event were thus fabricated after the fact to provide a support for the Comintern's policy of united fronts, a policy of betrayal and compromises with the bourgeoisie on the world arena.

In 1917, the proletariat steeled itself during its struggle against Kornilov - it felt that the resistance against an insurgent general could be successful, whereas after the retreat of the July Days the proletariat was wary of the consequences of another premature confrontation with the state. To fight Kornilov was a decisive test for the proletariat and Bolshevism throughout Russia. The class passed the test splendidly and was soon to use its increased confidence in the October insurrection. But nobody spoke at the time of ‘military blocs' with Kerensky as the Trotskyists do today.

What Lenin feared was precisely the ‘theorisation' of support for Kerensky, or passivity in front of Kornilov's move against the Soviets. If Kerensky seemed to have no base at all in Petrograd during those days this didn't mean however that his power was totally spent in the countryside or the Army. The Bolsheviks sensed that although Kerensky was almost finished, his role had yet to be played out inside the Soviets. By understanding this, Bolshevism, which was still in the process of winning the majority in the Soviets, used the time to build up its forces for the final confrontation. As we have said, the Soviets in fact dissolved Kornilov's attempted coup on their own. During the Kornilov coup Kerensky's regime became a caretaker government, but it was necessary for the proletariat to go through the reality of the experience to grasp what the situation was. The proletariat had no intentions of repeating the unplanned insurrection of the July Days. It needed the test of events to realise that the situation in the main centres had finally shifted in its favour - that the soldiers and peasants supported the transfer of power to the Soviets.

Soon after Kornilov's coup was defeated, the Russian Army suffered fresh defeats in its last offensives against Germany; for a while it appeared that the German Army could take Petrograd. In this context, it is revealing to see how even the threat of the ‘German Kornilovists' did not result in Bolshevik calls for ‘military support' for the Kerensky regime in its war effort against Germany. According to the Trotskyist logic, this should have been the case. On the contrary, Lenin never proposed to defend Kerensky even after the fall of Riga had made a German advance towards Petrograd an enormous danger. In a letter to the Central Committee (September 1917), he wrote: "We must take power now because the impending surrender of Peter will make our chances a hundred times worse."

He also stressed that while Kerensky and Co. headed the Army, it was not in the power of the Bolsheviks to prevent Petrograd's surrender. Moreover, Lenin went on to insist that as long as the proletariat was in power, the Bolsheviks would continue to be defeatists, not ‘defencists', even if this meant that their chances for an insurrection would be made a ‘hundred times worse'. www.marxists.org/archive/lenin/works/1917/aug/30.htm [15]

Conclusion

The proletariat's position of course can never be ‘neutral' when confronted with onslaughts by the bourgeoisie. It must take the offensive by generalising its struggles; it must prepare its forces to destroy all factions of capital without ever leaving its own terrain ‘militarily' or ‘technically' to support one gang of capitalist butchers against another.

The whole epoch opened up in 1917 has deepened these fundamental lessons for the proletariat. Furthermore, history will never again see the same constellation of forces that appeared in Russia in 1917. The actors have changed fundamentally - the ‘compromisers' have become capitalist executioners everywhere and the proletariat has also had ample time to reflect upon its own terrible defeat and illusions which allowed it to happen. It will no doubt in the coming revolutionary wave tend to climb to heights never seen before in the last revolutionary period, precisely because its experience in the intervening half century has taught it much about bourgeois democracy.

The mystifications about the Kornilov coup are just another pack of lies the proletariat will have to dispel in practice, in the merciless struggle waged by the workers' councils against all capitalist factions, left and right. This is the real lesson of the proletariat's resistance to the Kornilov coup, a lesson of intransigence and self-activity which will never be erased by the word-juggling of the counter-revolution.

Nodens (August 1977)

History of the workers' movement:

Heritage of the Communist Left:

- The "united front" [17]

Welcome to the ICC nucleus in Brazil

- 2632 reads

We would like to inform our readers about the creation of an ICC nucleus in Brazil. This will contribute significantly to the development of the political presence of our organisation in the most important country in Latin America – a country which has the biggest industrial concentrations in this region and some of the biggest internationally. There also exists in this country a milieu of proletarian political groups and of elements drawn towards revolutionary positions. We have already mentioned in our press and on our website in Portuguese about the Workers’ Opposition (OpOp), including the following events: the holding of joint public meetings and the publication of a common statement on the social situation; the publication on our Portuguese language site of an account of a debate between our two organisations on historical materialism; and texts by the OpOp which we consider to be of particular interest. As an expression of this mutual interest, OpOp also participated in the work of the 17th Congress of our section in France and the 17th International Congress.

In Sao Paulo there is also a group in formation, influenced by the positions of the communist left. We have recently established regular political relations with this group, including joint public meetings.

We obviously hope that our collaboration with these groups will be increasingly close and fruitful. This perspective is not at all in contradiction with our aim of developing the specific political presence of the ICC in Brazil. On the contrary, our permanent presence in this country will make it possible to strengthen the collaboration between our organisations, all the more so because between our nucleus and the OpOp there is already a long shared history, based on mutual respect and confidence.

The creation of our nucleus is the concretisation of work that the ICC began over 15 years ago. This work has intensified in recent years through the contacts we have made with different groups and elements, and through the holding of public meetings in different cities, some of which – those held in the universities- have been extremely well attended. For us this is not the end of a process but a significant step in the development of the positions of the communist left on the South American continent. Far from being a Brazilian exception, this event is part of the same phenomenon of the appearance of groups all over the world, which is the product of the revival of struggles on a world scale and of the tendency of the working class to give rise to revolutionary minorities.

ICC June 07.

Life of the ICC:

- Congress Reports [18]

Capitalism can’t save us from ecological disaster

- 2949 reads

Global warming is more and more a headline issue. In February Working Group I of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) met in Paris. They announced that the accumulation of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere, caused by the burning of fossil fuels, was "very likely" the cause of global warming. Before that announcement they had been more cautious in their level of certainty. In the report published they estimated that world temperature rises would be between 2 and 4 degrees centigrade by 2100. This makes it the fastest temperature rise in so short a period that the world has seen.

Working Group II met in Brussels in April to discuss the possible implications for the planet. Unsurprisingly it wasn't great news. Floods, drought, extreme weather, species extinction were all featured in this catastrophe. The worst-case scenario could see humanity itself disappear as planetary conditions become impossible.

At the end of April, in Bangkok, the 120 national delegates of the third working group of the IPCC met to look for solutions. Ogunlade Davidson, the co-chair, promised that "solutions are possible and can be achieved at a reasonable cost". Hurrah! The world is saved in the nick of time. We are told that capitalism can save the planet and make a good profit doing it at the same time. A miracle!

What are these miraculous solutions? IPCC chair Rajendra Pachauri invites us to look to the example of former US President Jimmy Carter who in the 1970s recommended everyone should lower the heating in winter and wear a pullover. He did not forget to congratulate the Japanese Prime Minister who has called on executives to forgo their ties so that air conditioning could be lowered. Mr Pachauri also recommends vegetarianism to reduce emissions from cattle. So the solution is to wear a pullover in the winter, take off your tie in the summer and become a vegetarian?

Of course the IPCC makes more "serious" suggestions, including the development of non-polluting energy sources (wind, solar), buildings becoming more energy efficient, a move from road transport to rail and waterway, collection and sequestration of CO2 etc.

There is one thing nagging the conscience of the bourgeoisie: how much will this all cost? The IPCC are eager to dispel fears, claiming that stabilisation of CO2 at today's levels by 2030 would only require a reduction of 0.1 % in annual growth. A drop in the ocean, but maybe a drop too many. Stephen Singer of the World Wide Fund for Nature said that no government would act if it felt its economy would be harmed. James Connaughton (head of the White House Council on Environment Quality) said that measures recommended at the conference "represent an extremely high cost" even "involving a recession". Jacques Chirac, even though a keen supporter of the findings, said that the cost would be "considerable".

In the capitalist world for a nation to finance the reductions in CO2 and make its economy "clean" means to be swept aside by its rivals in the world market. Who will jump first? Obviously nobody.

It can come as no surprise that the G8 meeting in Germany produced so little to solve global warming. Despite Tony Blair's optimism there was no more than a vague intent to act sometime in the future, but not now. The only "solution" that is posed is at the individual level with "what you can do to save the planet" campaigns.

As we said in the International Review issue 129:

"The constant eco-message from the governments is that "saving the planet is everyone's responsibility" when the vast majority is deprived of any political or economic power and control over production and consumption, over what and how things are produced. And the bourgeoisie, which does have power in these decisions, has even less intention than ever in satisfying human and ecological needs at the expense of profit" (‘Twin Track to Capitalist Oblivion [19] ').

Capitalism can offer humanity no solution to the problems it has caused, and this is becoming more and more evident. But this raises the question: what is the real solution? And here lies a source of hope, because the dead-end reached by the capitalist mode of production is a powerful argument in favour of destroying capitalism and installing a new mode of production, a higher form of social organisation where production is geared not towards the insane ‘growth' of capital but the rational needs of man.

Ash 6/7/7.

General and theoretical questions:

- Environment [20]

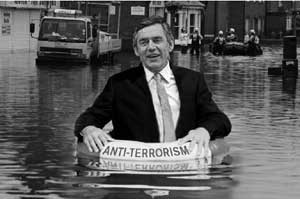

Floods in Britain: The state is no protection

- 2576 reads

Planning is not just a matter of cleaning up and rebuilding, it is also a question of taking precautions against future disasters. The Sunday Times (1/7/07) reported that the government's current spending review, to be published in the autumn, envisages "our resource settlement over the next three years will be flat cash in line with our current 2007-08 baseline (a real-time reduction in funding) with any growth limited to capital investment". This would be entirely in line with the US state's failure to maintain the levees needed to protect New Orleans (see ‘Hurricane Katrina: a capitalist-made crisis', ICC Online). Ministerial denials about a cut in spending do not absolve capitalism from its responsibility for exacerbating the risk of flooding. There has been a surge in house building on flood plains since 1945, in spite of the worst flooding on record which took place in 1947 - due to the melting of thick snow on that occasion, rather than heavy rainfall. 1.7 million homes are at risk because of this. Even after the Environment Agency started objecting to house-building proposals for flood plains, 20% were still allowed and 160,000 homes are planned for the Thames estuary.

Alongside all the talk of the limiting carbon emissions and climate change, there are those who talk about the need to adapt to whatever level of global warming we face. The response to the floods in Britain today, like the response to Hurricane Katrina in the USA, or the Asian tsunami, show that capitalism cannot be trusted with that adaptation. As far as our rulers are concerned the poor and the working class can be left to rot, and the future sacrificed in the hope of short term profitability.

Alex 7/7/7.

Geographical:

- Britain [2]