May 2023

- 45 reads

Overproduction and Inflation

- 398 reads

2023 introduction

Fifty years since the article below first appeared, half a century of butchery and growing barbarism, and capitalism today is being wracked before our eyes by a hitherto unseen convergence of destructive tendencies, each inter-acting with and deepening the other: ecological crisis, the mad march to wider and wider warfare and the open sores of economic convulsions.

Concerning the ‘economy’ its woes are illustrated at the time of writing by

- Growing signs of financial instability in 2023 including bank and ‘digital currency’ collapses and ‘rescues’, pouring ‘good money after bad’ (China, the US, Switzerland even!); trade wars (US boycotts of Russia and China; Brexit fall-out, ‘de-globalisation’); business failures; neglect of infrastructure and social provision (collapse of road networks, failing health systems, etc);

- the accumulation of unprecedented global, national, governmental and private debt “Global debt has hit a record $300 trillion [a trillion defined as a million millions – silly numbers!], or 349% leverage on gross domestic product. This translates to $37,500 of average debt for each person in the world.” (S&P Global [1]) Or, according to the International Monetary Fund [2] (IMF), debt as a percentage of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) rose from approx. 120% in 1970 to 220% in 2020. A gross under-estimate. Printing money, ‘quantitative easing’, devaluations of currencies, ‘fictitious capital’ ‘kicking the can down the road’ … these are mechanisms and euphemisms for the accumulation of debt, of existing on the ‘never never’ (except never is becoming now!) of attempts to compensate for chronic, ‘institutionalised’ over-production and lack of solvent demand;

- and in particular, hitting ‘the weakest’ (ie the working class) hardest, inflation, the remorseless rise in prices of life’s necessities – energy, food (1), shelter, transport – as opposed to the actual purchasing power of wages, pensions or ‘welfare benefits’.

Inflation is the signifier, the unmistakable sign, that the destructive tendencies inherent in capitalist social relations are being directly and openly offloaded onto society in general and the working class in particular. 5%, 10% 200%, depending on where you live (and to what class you belong). Inexorably the ‘cost of living’ spirals. Their ‘order’- in reality bourgeois anarchy and cut-throat competition - has summoned up this wraith which they seek to tame by stepping up trade wars and lowering the costs of production (increasing automation, use of artificial intelligence, and in particular holding down wages once more, claiming that wage rises to compensate for inflation are … the cause of inflation!) In the face of both ‘rampant’ and ‘sticky’ inflation (2), and after decades of ‘cheap loans’ (ie the accumulation of debt in order to keep the system afloat) the ruling class has been raising rates of interest, making debt repayments even more burdensome, summoning up the spectre of local and global recession – a slump which in reality has beset world production and trade since the last ‘Great Financial Crisis’ of 2007-2008. (3)

The article which follows correctly seeks to source the roots of inflation in the very entrails of capital accumulation itself:

- over-production – the tendency to produce commodities as if there’s no barrier to consumption, whereas the restricted purchasing power of the masses can never ‘buy back’ what they themselves have collectively crafted;

- a tendency which is multiplied, quantitively and qualitatively heightened, in the period of capitalism’s decline, towards permanent warfare or preparations for war between states, which entails a growing production which is actually unproductive: waste production, production destined for destruction, particularly armaments - the destruction of capital including human capital, culture and life.

As the article says: “In other words, inflation expressed the immense waste of productive forces which the system in decadence is obliged to resort to in order to keep itself alive. And since we are living in a society based on exploitation, inflation appears as the means by which the system puts the burden of its insoluble contradictions on the shoulders of the workers, by a continual attack on their standard of living.”

It's no accident that inflation has ‘taken off’ in today’s period when the resort to printing money and the consequent levels of unsupportable debt has collided with the costly eruption of the ecological crisis (fires, droughts, storms and, above all, the global Covid Pandemic) into the economic life of capital at the same moment that war involving the two largest states of Europe (Russia and Ukraine) breaks out, signaling a crazy rush to rearmament by major states across the world (including those defeated in World War II, Japan and Germany).

But while the working class can’t hold back the crisis of the environment, nor immediately halt the war in Eastern Europe, it can and has reacted to the renewed austerity and in particular to pauperising inflation with strikes and protests across the world after decades of relative quiescence. It is this collective struggle of the modern proletariat which permits and promotes a development of consciousness of what’s at stake in today’s situation in order to change it. (4) It’s as a contribution to this developing class consciousness of reality that we reprint the article from 50 years ago.

April 2023

Footnotes

- In support of their current wage claim, striking junior doctors in GB have illustrated their plight thus: in 2008 a junior doctor could be paid £9.60 an hour, which would be enough to buy 24 tins of Heinz baked beans which cost at that time 40p a tin. Today junior doctors can start on £14.09 an hour but this translates to just 10 tins of beans which now cost £1.40 per tin.

- “In releasing its World Economic Outlook [3] earlier this week, the IMF warned that slowing global growth, sticky inflation, the risk of financial instability coupled with structural factors like climate change and global fragmentation all contributed to the global economy entering a 'perilous phase'. Notably global growth was going to be led lower by declines in the Advanced Economies as recent tightening cycles hit home.” (ING Newsletter [4] April 2023) ‘Sticky inflation’ is what remains when ‘one-off’ price hikes like energy bills are absorbed one year later. It’s an admission that inflation is ‘baked in’ to the capitalist system and, in any case, while ‘headline’ inflation may fall, prices don’t return to their former levels.

- The article below was written after the UK Sterling Crisis of 1967 and the abandonment in the early 1970s of the international currency system, part of the Bretton Woods Agreement of 1944, and at the time of oil price rises instituted by the producers’ cartel OPEC. Since then, there hasn’t been a period in which economic crises and austerity haven’t been the order of the day, including but by no means exhaustively: a global recession in the early 1980s coupled with a decade-long ‘debt crisis’ in Latin America; the US stock market crash of 1987; a recession in the West in the early 1990s, ‘Black Wednesday’ in the UK in 1992 and further crises in Argentina, plus the collapse of the ‘Asian Tigers’ in 1997. The bursting of the ‘dot-com bubble’ in early 2000 was followed, of course, by the Great Financial Crash of 2007-2008 whose reverberations are still evident today.

- Capitalism is not a machine but a series of social relations. ‘Another World’ is indeed possible but it will be made by the exploited, producer class, the proletariat, which will have to be widely armed with the theoretical understanding of what capitalism is and how to go beyond it once political power has been conquered.

The analysis which follows first appeared in Révolution Internationale no. 6, new series (November-December, 1973), and in World Revolution no. 2, November 1974.

This article cannot attempt to analyse the underlying causes of the crisis which today affects the whole capitalist economy. (1) It will simply try to clarify some of the manifestations of that crisis from a revolutionary standpoint. In particular, it will look at one phenomenon which today most directly affects the working class: inflation.

Does the crisis exist?

Today this seems like a crazy question. Inflation, the crisis in the International Monetary System, plans for economic stabilisation, austerity measures, and international conferences of the bourgeoisie, have become daily preoccupations. Along with the repercussions of the Middle East war on the oil situation, which can only aggravate the problem, they are continually being discussed throughout the media. In the ranks of the bourgeoisie the 'pessimist' bloc is growing in number, and certain of their 'experts' do not shrink from writing, "Today, the worst is yet to come. We are heading for a collective suicide through excess of every kind, as in the film, Blow Out. It needs courage to say this because everyone would prefer to ignore it." (2)

If we still ask the question 'does the crisis exist?', it is because the evolution of the capitalist economy between 1972 and 1973 seemed to invalidate not only the fears of the scribblers of the bourgeoisie during the recession of 1971, but also the perspectives which we drew up in our article 'The Crisis' (R.I. 6 and 7 old series):

- Massive fall-off of international trade;

- Trade wars between different countries;

- Adoption of protectionist measures and collapse of customs unions;

- Return to autarky;

- Decline of production;

- Massive growth in unemployment;

- Drop in real wages of the workers.

Of these predictions, 1972 and 1973 have confirmed only the intensification of trade wars (through the expedient of monetary fluctuations) and the dislocation of customs unions (the problems faced by the Common Market). By contrast, wages for the moment have succeeded in following inflation (especially in France), unemployment has fallen since the beginning of 1972 and international trade has never done so well (annual growth of 10-20%). 1972 marks a clear recovery for world capitalism in relation to previous years, in particular for the US, which has achieved its greatest rates of growth since World War II.

Rates of Growth of Industrial Production

1963/70 1970/71 1971/72

France 5.95% 5.67% 7.21%

G. Britain 3.25 1.04 2.06

Italy 5.85 -1.76 2.39

W. Germany 6.28 1.76 2.12

USA 4.82 -0.18 6.09

These factors have led certain people to conclude that the world economy has overcome its worst difficulties and is heading for a new boom (it is worth pointing out that these voices of ‘optimism’ have found more recruits among certain leftists (3) than among the ‘official’ specialists who do not have so many illusions. Even before the Middle East war the latter foresaw a recession in 1974 - e.g., OECD and Giscard). In particular there was speculation around the possibility that inflation, such as developed in 1972-73, could ensure continued growth.

We shall attempt to explain why this inflation and this ‘mini-recovery’ can actually only presage a new round of difficulties for the capitalist economy.

Another phenomenon has led some to say that the present difficulties have nothing to do with a crisis of overproduction such as that of 1929. In 1929 the crisis broke out abruptly in the middle of a period of euphoria and expressed itself in terms of a collapse in the stock exchange. Today we have not seen such a collapse, neither in the stock exchange (4) nor in production, but essentially difficulties in the monetary system. It is thus a question of seeing what distinguishes the two periods and what they have in common, and of explaining how the monetary crisis is only a reflection of a markets crisis. This is what we shall do first.

Overproduction and monetary crisis

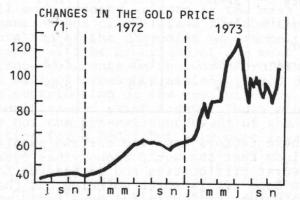

For several years the ‘International Monetary Crisis’ has been in the headlines of the newspapers. Devaluations of the dollar coming after re-evaluations of the mark, floating of the pound and speculations on gold, international conferences of governors of central banks and meetings of three, five or of forty-seven finance ministers. At the monetary level, everyone is in agreement in saying, “Yes, the crisis exists”. And for four or five years, it has been agreed that the ‘International Monetary System’ which came out of the 1944 Bretton Woods agreement is no longer suited to the contemporary needs of the world economy and that, consequently, it must be reorganised as quickly as possible. But in spite of these proclamations, the bourgeoisie has still not succeeded in resolving this crisis which far from diminishing has been continuously growing. In 1973 there was a devaluation of the dollar even more serious than the previous one (8.57% in December 71 and 10% in March 73), followed by another brutal fall in July as well as a sharp rise in the price of gold, the official price of which was trebled.

Changes in the gold price

Dollar exchange rates

|

|

31.03.1970 |

24.07.1973 |

|

German Mark |

3.7 |

2.3 |

|

Swiss Franc |

4.4 |

2.9 |

|

Pound |

0.42 |

0.39 |

|

Yen |

360 |

265 |

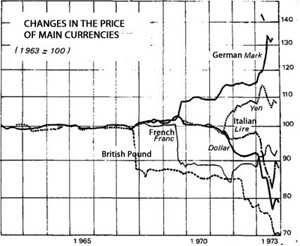

These fluctuations only reflect the general instability of currencies since 1967 (see chart below). It was only at the recent Nairobi conference that a small step was made towards beginning preparations for the reform of the International Monetary System. But in spite of the declarations and the rapprochement between extreme positions (actually between those aligned to the French and those aligned to the Americans) commentators agreed that nothing was settled and that the future was far from rosy.

Changes in the Price of Main Currencies

Why then this inability of the bourgeoisie to resolve their monetary problems and to come to an agreement about a new International Monetary system?

Is it because they are incompetent and do not know how to go about carrying out this task? The bourgeoisie certainly does not lack competent servants: for a number of years at the economic summit meetings, all the Nobel Prize winning academics have been at the bedside of the ailing International Monetary System concocting all kinds of magic potions for it. Their failure does not mean that they are imbeciles but simply that they are faced with an insoluble problem: to put the International Monetary System on its feet when it is the whole world economy which is sick, sick with an illness whose fatal solution can only be war or revolution.

In reality, currency has no independent existence in relation to the economy as a whole. There is money because there is exchange and it is because there is a need for a specific commodity to become autonomous in relation to others that money appears to take on a certain aspect of independence. And it is because the commodity lies at the heart of the capitalist mode of production that monetary problems are so important today.

The behaviour of currency at international level, its stability as well as its fluctuations, is a reflection of the conditions in which the essential mechanism of the capitalist mode of production operates: the valorisation of capital. This is all the more true today when the only basis of the value of a country’s currency is its ability to produce in a profitable way and face up to international competition.

In the past, paper money issued by the central banks had a systematic counterpart in gold or silver. Paper money was thus convertible into precious metals, whose social utility and embodied labour conferred a real exchange value on to bank notes which had then the former’s same value.

With the massive reduction in the rate of conversion of issued notes (5), that is to say the theoretical impossibility of converting a large part of the money in circulation into gold, the facts of the problem changed: henceforward, what guarantees the value of a currency is the possibility of buying commodities of the country in which it is produced. As long as that country is able to produce commodities which can be viably exchanged on the world market (viable in quantity and price) the world has confidence in its currency. On the other hand, if the commodities produced by that country (country A) can no longer be sold because they are more expensive than those of other countries, the stockholders of country A rid themselves of its currency in favour of the currency of a country which is selling its commodities. The currency of country A, having no counter-part in any real value, thus loses the confidence of its stockholders and begins to flounder (6). This has been a common misfortune of the currencies of underdeveloped countries for some years: their almost incessant decline expresses the chronic economic difficulties of these countries.

But the phenomenon which we are dealing with has a different significance from the fall of the Argentinian peso, the Guatemalan quetzal or the kwacha of Malawi. The currency floundering today, which in three years lost 37% of its value in relation to the mark, 34% in relation to the Swiss franc, 26% in relation to the yen and even in relation to the pound sterling – this currency is none other than the dollar; the currency of the nation which produced 40% of the world’s wealth and which engages in 20% of international trade, the currency which for this reason has become the universal money of the world.

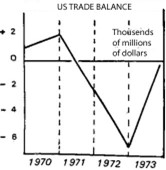

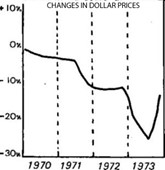

The recent slump of the dollar has expressed the loss of competitiveness of American commodities in the world market as well as in its internal market, against those of Europe and Japan. And this is illustrated by the fact that it was enough at the end of July that the American trade balance was declared to be on an upswing for the dollar to enjoy a spectacular revival.

US Trade Balance

Changes in Dollar Prices

But this phenomenon goes far beyond the confines of the American economy, having serious repercussions on the world market: to the extent that the dollar remains the universal money, its crisis is the crisis of the International Monetary System. To the extent that the US is still the greatest commercial power in the world, its own difficulties in finding outlets for its commodities is a sign of a world saturation of markets, both phenomena being clearly interrelated in a very close way.

As we explained in our previous article (7), the underlying causes of the present crisis reside in the historical impasse in which the capitalist mode of production has found itself since the first world war: the great capitalist powers have completely divided up the world and there are no longer enough markets to allow the expansion of capital; henceforth, in the absence of a victorious proletarian revolution, the system has only been able to survive thanks to the mechanism of crisis, war, reconstruction, new crisis, etc. Having now (from the middle of the 60s) reached the end of the period of reconstruction, capitalism is once again haunted by the spectre of generalized overproduction.

The battle to which the big countries are now devoting themselves, through devaluations, floating the currency etc., and which has dislocated the old monetary system, is only an expression of the attempts of each country, especially the most advanced, to push the difficulties of the world economy onto others. In this little war, one country is still better armed than its rivals: the United States. The US derives its strength from its productive and commercial power, as well as from its political and military influence (in order to get the European countries to tow the line, the US regularly threatens them with withdrawing its troops and atomic umbrella). But, more paradoxically, the US derives its strength from its weakness, that is from its debts: the hundreds of billions of dollars at present circulating in the world are in fact debts contracted by the American economy and the holders of this currency have every interest in seeing their debtors spared from any catastrophe that might prevent them from honouring those debts. That is why other countries are forced to accept American dictates, whether they like it or not (8):

- re-evaluation of their currency (yen, mark, florin, Belgian franc, etc)

- brutal and repeated devaluations of the dollar, followed by the floating of the currency at the lowest possible rate, particularly encouraged by the American government (cf its attitude in July 73) …

measures which have the twofold advantage

- of cutting the value of American debts

- of lowering the price of American products on the world market, thus making them more competitive (Belgium’s recent buying of American airplanes instead of French Mercuries is one of the most spectacular illustrations of this, because it shows the futility of the EEC in the face of the crisis…).

For the reasons which we saw in our previous article, the crisis of overproduction hits the most powerful capitalist country first of all, but because it is the most powerful, this country is able to shift the burden of its difficulties onto the shoulders of others.

This is what is happening today: the massive devaluation of the dollar has allowed American commodities to regain competitiveness vis-à-vis those of Europe and Japan, and the American trade balance to regain its equilibrium. But this can only be a brief respite for the US: the invasion of other countries by US commodities will lead those countries to cut down production, as well as their labour force, which will diminish demand for American goods and thus have repercussions on the American economy. In sum, the monetary crisis expresses the fact that the world market is today too narrow for capitalist production, and even the bourgeois economists have understood this, even though for them, empiricism remains the rule, and ‘will’ is held to be an economic factor:

“The basic cause of the monetary crisis can be summed up in one phrase: every capitalist country, in order to maintain full employment, wants to reduce its trade deficit (the difference between imports and exports), or to keep it from growing excessively. These different national ‘projects’ are incompatible with each other, to the extent that the global surplus which results from the totality of these projects cannot be reabsorbed by the rest of the non-capitalist word.” (9)

Marx said somewhere that it was only in moments of crisis that the bourgeoisie became intelligent., that it began to understand the reality of its present system and its contradictions. The present crisis must be well advanced for the bourgeoisie to begin to do what most ‘Marxists’ of this century have refused to do: to recognize the validity of Rosa Luxemburg’s thesis on the necessity for the existence of non-capitalist markets for the development of capital (10)

What are the differences between today’s crisis and 1929?

Since World War I capitalism has been in its epoch of decadence. The crises of this period are different from those of the last century because they can only be resolved by imperialist wars. In this sense they can no longer be considered as cyclical crises of growth but as the system’s death-rattles. The present crisis obviously falls into this category but it is different from the greatest crisis of the past – that of 1929 – by virtue of the fact that it has begun as a monetary crisis and not as a catastrophe on the stock exchange like that of ‘Black Thursday’.

How are these differences to be explained?

The reconstruction period which followed World War I had the following characteristics:

- armaments production was considerably reduced;

- reconstruction was applauded by the economists of the time who saw in it the remedy, discovered at long last, of all capitalism’s ills: credit, and particularly private banking credits which developed at a dizzying rate;

- after the omnipresent intervention of the state in the economy during the war period, there was a certain return to ‘laissez-faire’.

But the reconstruction following Word War II was distinguished by:

- the maintenance of an arms economy (the Cold War);

- the systematic presence of the state in the economy (arms purchases, nationalisations, budgetary policies) which was reflected on the ideological level by the success of neo-Keynesian conceptions;

- a progressive weakening of the role of the stock exchange: important transactions of capital now took place directly between the big enterprises and often under government control.

It is because the state now controls the whole of economic life and because governments have learned the lessons of the past that the present crisis does not appear in this abrupt way, that its effects are cumulative and that it begins to manifest itself on the terrain par excellence of governmental manipulation: the monetary system.

Today’s endless international conferences where governments constantly try to form a common front without being able to stop dumping the crisis on each others’ shoulders are to the present crisis what ‘Black Thursday’ was to the crisis of 1929.

The difference between the two periods of reconstruction also explains the existence of a relatively new phenomenon which today is breaking out violently all over the world: inflation.

The interpretations of inflation

Inflation is a phenomenon which has been with us since the beginning of the century but which has had its golden age since World War II. But even the post-war rates of inflation, considered for a long time to be disturbing, have in recent years been completely left behind.

What is striking is that the most important rise in prices corresponds exactly to the ‘mini-recovery’ of 1972. This is not a fortuitous phenomenon but on the contrary is proof of the interpenetration of the different aspects of the present crisis. In order to understand today’s galloping inflation, we will first have to explain the general phenomenon of inflation as it has appeared since World War II, particularly in its ‘rampant’ form.

There are as many interpretations of inflation as there are schools of economic thought. For some it is the excess of demand over supply which leads to a constant rise in prices (demand inflation): such people fail to see that world capitalism has for a number of years been unable to adjust supply to this excessive demand, since for a long time it has been clear that the limits to economic growth are not technical problems of expanding production but a problem of expanding markets (the existence of unemployment and under-utilised capital). They also fail to understand that the greatest burst of inflation of the post-war period corresponded to its most serious recession: that of 1971. Faced with a situation which they can’t explain, the only thing the economists have managed to do is to invent a new word to describe it, ‘stagflation’.

Annual Increase in Consumer Prices (in Percentages)

1st ¼ 2nd ¼

1952/62 1962/71 1972 1973 1973

Belgium 1.1 3.6 5.5 6.9 7.3

France 3.7 4.2 5.9 6.4 7.1

W. Germany 1.3 3.0 5.7 7.7 6.7

Italy 2.3 4.1 5.7 8.8 11.1

Netherlands 2.5 5.2 7.8 7.6 8.1

USA 1.3 3.3 3.3 3.3 4.5

Japan 3.3 5.7 4.5 7.1 10.5

UK 3.0 4.7 7.1 7.9 9.4

Switzerland 1.4 3.8 6.7 7.7 8.2

Canada 1.1 3.1 4.8 5.9 7.3

Under-utilisation of capital and labour power in the USA

|

|

1951 |

52 |

53 |

54 |

55 |

56 |

57 |

58 |

59 |

60 |

61 |

62 |

63 |

|

A |

3 |

1 |

2 |

13 |

8 |

11 |

15 |

24 |

15 |

15 |

20 |

17 |

17 |

|

B |

3 |

2.7 |

2.5 |

5 |

4.3 |

3.8 |

4.3 |

6.8 |

5.5 |

5.6 |

6.7 |

5.6 |

5.7 |

A= % of unused productive capacity

B= % of unemployed labour power

For other ideologues, there is inflation because there is a rise in production costs (cost inflation) and as these are in turn determined by certain price levels (of raw materials, services, machines, consumer goods involved in variable capital…) this is as good as saying that prices rise because there is … a rise in prices. (11)

According to the first interpretation the current brutal rise in prices is explained by an exceptional demand for all goods above all for raw materials and agricultural products which have undergone unprecedent price rises (in six months the price of certain raw materials and of grain doubled, the price of meat went up 20-30%, and so on). These rises then have repercussions on all the commodities which use these basic goods (the second interpretation) and, among others, on food products, which further increases the price of labour power, the main consumer of these products.

Every confusion, if it is to be at all credible, must contain a degree of truth: in this sense, this interpretation of today’s runaway inflation is partially correct. In fact it is the case that there have recently been bad harvests in basic products like grain, and consequently such a massive demand (including considerable purchases by the USSR) that the prices of these and of all agricultural products have shot up (12). And the record prices of oil obviously have a lot to do with contemporary perturbations in prices generally.

By the same token, the pressure of demand from buyers who want to buy in advance of price rises has contribute to these perturbations, and this is all the more true now since the practice of anticipating tariffs, currently in vogue amongst suppliers, became generalized with the first waves of galloping inflation.

Thus we have a series of phenomena: inflation by demand, by costs, by speculation, and rises in tariffs, which have all been described and analysed at length in recent times and which undoubtedly do contribute in part to the contemporary panic. But all these interpretations postulate:

- that demand has exceeded supply since the last war, and especially in recent years;

- that inflation exists because there is inflation already.

We have already dealt with the drawbacks of the first hypothesis; as for the second, it is enough to say that it is a plain tautology.

What we have to determine is why, for several decades, costs of production as a whole have continued to rise when in the same period the productivity of labour has reached unprecedented levels of growth.

Some of the most reactionary factions of the bourgeoisie, as well as certain ‘marxists’, have a ready answer to this, though they may formulate it differently:

- for the first, it is the growth of ‘wage costs’ imposed by the action of the unions which is responsible for the rise in production costs and thus of prices. To overcome inflation, it is therefore necessary to smash the power of the unions.

- For the second, the class struggle, the motor of the whole of social life, is at the origin of the rise in production costs, to the extent that it forces the bourgeoisie to grant wage rises to the workers.

Even if one concedes that the intensification of workers’ struggles is one of the contributing elements to the evolution of rampant inflation (1945-1967) into galloping inflation (after 1969) (13) this hypothesis is still unable to answer the following questions:

- why did inflation continue even during those years when the class struggle was particularly weak (the 50’s and early 60’s), when in the last century [the 19th] the most powerful struggles did not set back the tendency for prices as a whole to fall?

- for what mysterious reason did the class struggle intensify towards the end of the 60’s?

The inability of the ‘wage costs’ hypothesis to account for these phenomena thus shows that, in the last resort, it is not prices which run after wages but wages after prices.

Another explanation, in which the Communist Party has become a specialist, consists in saying that it is the super-profits of the monopolies which are responsible for rising production costs. Therefore all that is needed is for the left to come to power to deal with these monopolies (eventually to nationalize them) and thus overcome inflation. Just like that!

We won’t waste much time addressing ourselves to this demagogic explanation (what are the monopolies but expressions of the general tendency of capitalism towards the concentration of capital?)We will simply examine the content of this notion of the monopolies’ super-profits.

Firstly, let us suppose that a given enterprise had a total ‘monopoly’ of the market for a product. In such a hypothetical case, it is obvious that this enterprise would no longer be obliged to fix the price of its products in relation to their real value. The law of supply and demand would not apply, since customers would be unable to go to any other supplier; this enterprise would, theoretically, be able to raise its prices as high as it wanted to. Such a situation could not exist in reality since one would then see the appearance of other enterprises which, even with a lower productivity, would be able to offer their goods at lower prices and thus corner the first one’s markets.

And in reality, there is no such thing as a true monopoly. No market in the world (except perhaps for very specialized products and in insignificant numbers) is the exclusive property of one enterprise. What on the other hand do exist are cartels, ie more or less temporary ententes between big companies, which try to restrict their competition and divide up the market.

These ententes are still always at the mercy of the fluctuations of the world market and are in fact only minor truces in the perpetual war between different factions of world capital (14). For this reason even the monopolies which so many decry are not in a position to freely dictate their prices and provoke inflation, even if they are able, via the cartel mechanism, to oppose, within certain limits, tendencies which lower prices and therefore become instrumental in the international transmission of this inflation.

In fact, these ‘monopolies’ and ‘cartels’ have been in existence for a long time and were already a major preoccupation of economists at a time when inflation was unknown. They therefore cannot be used to furnish an explanation for a phenomenon which appeared well after they did. This argument is equally valid for the thesis according to which it is the falling rate of profit which is responsible for inflation: in order to struggle against this fall, it is argued, the monopolies tend towards fixing their profits above the rate allowed by the organic composition of capital, thus provoking a general imbalance towards rising prices. In fact, the tendency of the rate of profit to fall has operated throughout capitalism’s existence and did not prevent prices from falling throughout a whole epoch. If one admits that it is partly through the fall in the rate of profit that the ‘monopolies’ feel the contradictions of the system and are obliged to increase their prices, this explanation still doesn’t enable us to understand the existence of inflation. Once again, one could say that monopolies and cartels are instruments of inflation, not its cause.

The real causes of inflation

The fundamental causes of inflation are to be found in the specific conditions of the capitalist mode of production in its decadent phase. Empirical observation allows us to see that inflation is fundamentally a phenomenon of this epoch of capitalism and that it manifests itself most sharply in periods of war (1914-1918, 1939-45, Korean War, 1957-8 in France during the Algerian war…) i.e. at times when unproductive expenditure is at its highest. It is thus logical to consider that it is by beginning with this specific characteristic of decadence, the immense role of armaments production and unproductive expenditure in general in the economy (15) that we can attempt to explain the phenomenon of inflation.

As we saw above, the decadence of capitalism is caused by the growing and increasingly insurmountable difficulties which the system encounters in finding outlets for its commodities. At the level of each state, these difficulties provoke a constant increase in unproductive expenditure dedicated to the maintenance of a system which is historically condemned to death:

- expenditure on armaments which allow each state to defend tooth and nail the position of its national capital against rival capitals

- expenditure on the state apparatus which, faced with a society in decomposition, is forced to exert a Moloch-like domination over the whole of social life (police, administration, judiciary);

- expenditure on marketing, advertising, on research dedicated to making products more and more ephemeral, costs which are all consecrated in the marketing of commodities and not their production.

The existence of unproductive expenditure in capitalist society is not in itself a novelty. It is a fact of all societies and especially those based on exploitation. It is a rule under feudalism, for example, where the nobility consumed the greater part of the social surplus product in the form of luxury goods. It manifests itself under capitalism from the beginning in the form of the state, of the army, the church and in the consumption of the capitalist class. But what is fundamentally new in the period of the decline of capitalism as with the decline of other systems, is the magnitude of these expenditures in relation to productive activity as a whole: at this level quantity becomes quality.

Today, in the price of each commodity, alongside profits and the costs of labour power and of constant capital used in production, there is a greater and greater involvement of expenses which are indispensable to its being sold on a more and more saturated market (from the salaries of those engaged in marketing to the amount set aside to pay the police, the functionaries and soldiers of the producer country). In the value of each object, the part which embodies labour time necessary for its production becomes smaller and smaller in relation to the part embodying human labour imposed by the necessities of the system’s survival. The tendency for the weight of these unproductive expenses to annihilate the gains of labour productivity manifests itself in the constant rise in commodity prices.

In other words, inflation expressed the immense waste of productive forces which the system in decadence is obliged to resort to in order to keep itself alive. And since we are living in a society based on exploitation, inflation appears as the means by which the system puts the burden of its insoluble contradictions on the shoulders of the workers, by a continual attack on their standard of living.

Whether one considers the history of the twentieth century over short or long periods of time, one can assert that the growth of military expenditure (and unproductive expenditure in general) is always an inflationary factor. Over short periods, we have already said that wars lead to record rates of inflation. Over long periods, it appears that the uninterrupted rampant inflation since World War II is the corollary of the massive armaments production from the Cold War to today, since the inter-war period of disarmament was marked by a slowing down or disappearance of inflation.

Galloping Inflation

As regards the contemporary upswing in prices on the international scale, all the elements mentioned above have played their part.

For example, the rise in agricultural prices is linked to a real scarcity, but it seems absurd that in 1973 humanity should still be subjected to the whims of nature as it was in the Middle Ages or in antiquity. In fact, the real cause of this sudden scarcity is the whole policy of restricting agricultural production (subsidies for pulling up crops, for leaving land fallow, destroying stock, etc) caried out by the great powers since World War II. Anxious to obtain outlets for agricultural products on a saturated world market, capitalism, in limiting production to the lowest its needs require, has put itself at the mercy of the first bad harvest to come along. Paradoxically, it is therefore overproduction which is still at the origin of today’s scarcity of agricultural products and thus of the price rises this leads to.

One could equally say that the world upsurge in class struggle since 1968 is not absolutely outside the process of runaway inflation, but there again it must be made clear that this upsurge is in itself a consequence of the worsening living standards of the workers, manifested, among other things, through price rises, a deterioration which results from the exacerbation of the contradictions of the capitalist system. Even if it may partially increase it, the class struggle is not the cause of inflation but its consequence.

In the same way, we have seen that the bourgeois explanations about the role of speculating (buying, and then raising prices) on the curve of prices are not entirely without foundation.

Thus we have a series of factors which enable us to partially explain the change from rampant inflation to galloping inflation. It is necessary to add another factor which will allow us to understand how the recession of 1971 contributed to strengthening the inflationary spiral of 1972-73. For a number of years, the capitalist system has been characterized, apart from the century-old existence of an ‘industrial reserve army’, by a chronic under-utilisation of capital. This phenomenon means that, apart from the unproductive expenditures already referred to, the system must support the liquidation of a proportion of constant capital which, once created, is no longer engaged in production and must therefore appear as unproductive expenditure. In other words, the cost of production of a commodity created under these conditions will incorporate, alongside the fixed capital actually consumed in it, the unemployed part of this fixed capital (which nevertheless is paid for).

When one observes that the rates of utilization of the productive capacities are respectively according to the INSEE)…

USA 88% in 1969 71% end of 1971

UK 96% in May 69 86% in Feb 72

Belgium 88% in Oct 69 82% in Jan 72

Italy 84% in May 69 74% in Feb 73

W Germany 92% early ’70 85% July 72

…one can see how the recession in 1971 has affected the upswing in prices in 1972-73.

To the effects of the under-utilisation of constant capital must be added, during the same period, those of the growth of unemployment. In fact, even if the assistance doled out to the unemployed is often derisory, it nevertheless represents an unproductive expenditure which the whole society must bear and which thus has repercussions on the cost of producing commodities.

Unemployment and under-utilisation of productive capacities are therefore to elements of the recession of 1971 which help to accentuate still further the inflationary explosion of 1972-73.

Faced with a situation of galloping inflation, what measures can the bourgeoisie take?

The failure of the struggle against inflation

As we have seen, the fundamental causes of inflation reside in the contemporary mode of existence of the capitalist system which is manifested by an inordinate development of unproductive expenditure. In this sense, there could not be an effective struggle against inflation without a massive reduction in this expenditure. But, as we have also seen, this expenditure is absolutely indispensable to the system’s survival, which means that the problem of the struggle against inflation is as insoluble as that of squaring the circle.

Being unable to attack the fundamental causes of the ailment, the bourgeoisie is forced to attack its consequences. It is in this way it has attempted to carry out a series of measures:

Budgetary economies;

Putting the brakes on demand by limiting credit;

Price restrictions;

Wage restrictions.

Budgetary economies are attempts to deal with the fundamental causes of inflation. In fact, to the extent that this is impossible without touching the foundations of the system, policies of ‘budgetary rigour’ can signify nothing but policies of austerity and restrictions on ‘social spending’.

Thus we have seen Nixon liquidating the politics of the ‘Great Society’ started up by Johnson. But in any case this measure has not been enough to prevent the existence of deficits of dozens of billions of dollars in the last two American budgets, deficits which, to the extent that they are covered by the issue of bank notes, i.e. the injections into the economy of a mass of currency which does not correspond to the creation of real value, are manifested in a fall in the value of money and a corresponding rise in inflation.

In general, to the extent that purchases by the state constituted one of the markets for capitalist production during the period of reconstruction, these restrictions have had the effect of accentuating today’s recession. Governments are thus faced with a dilemma: inflation or recession, without really being able to prevent one by resorting to the other.

Policies of limiting credit, in so far as they propose to cut demand and thus to reduce markets, are also faced with the same dilemma: inflation or recession. Moreover, these policies of ‘dear credit’ have the result of increasing costs of paying off invested capital, costs which have repercussions on the prices of commodities and lead to more inflation.

As for price restrictions, these have now become the background for a well-worn scenario: prices do not move as long as they are subject to government regulation, but as soon as this stops, the opportunity arises to use speculative bonds, bonds which are simplified by the fact that many suppliers, having awaited the end of restrictions in order to carry out their deliveries, have created an imbalance between supply and demand beneficial to the latter. Far from holding down inflation, price restrictions substitute an inflation by stops and starts producing a continuous inflation. Thus these restrictions do not have the desired effect but, to the extent that the system is unable to fiddle with its own laws and that those laws impose upon it a continual rise in prices, there follows a major disequilibrium which of necessity expresses itself in recessions: here again the bourgeoisie is confronted with the same dilemma.

Wage restriction is the only measure which involves not only economic criteria but also the balance of forces between the classes. In this sense the failure or (temporary) success of such policies is conditioned by the level of combativity among the workers. In the current period, when the working class is waking up after 50 years of defeat, every major attack on its living standards is met with violent reactions (May ’68; Gdansk 1970, the 1971 British miners’ strike which obtained 30% increases in a period of wage restrictions, the recent strikes of German metal workers). Consequently, the bourgeoisie, in spite of several attempts, continues to hesitate to impose the draconian austerity measures on the working class which the situation increasingly demands: the reaction to such measures frightens the bourgeoisie so much that they dare not resort to them.

If attacking the workers’ living standards is the only policy remaining to the bourgeoisie in its fight against inflation it is as yet a policy which it can only implement with the greatest circumspection.

********

For a number of years world capitalism has been walking on a tightrope: on the one side, the descent into galloping inflation, on the other, the descent into recession. The recession of 1971 and the inflationary spiral of 1972-73 are a flagrant illustration of this situation. What the mini-recovery of 1972-73 really hid was a failure by governments in the face of inflation which allowed the latter to reach spectacular levels. The temporary liberation of credit, speculation by buyers on price rises as well as the ‘adjustment’ in relation to 1971 (the recovery was all the more spectacular in that it followed a year of stagnation) having been at the root of this recovery in 1972, some people have tried to see inflation as a remedy for the problem of overproduction: from the moment that inflation remained more or less uniform in each country (it being enough to do no worse than your neighbour), galloping inflation would be the ‘medicine’ which today’s economies lack. After all, what would it matter if prices rose by 10 or 20% if at the same time international trade could carry on?

Such a possibility, quite apart from all the reasons which have allowed us to explain the phenomenon of inflation, is itself quite absurd. In reality, one of the basic functions of money is to be a measure of value, a function which facilitates all its other uses (as a means of circulating commodities, of saving, of payment, etc.) Once it reaches a certain rate of depreciation, a currency can no longer fulfill this function: you cannot operate on the market with a currency whose value changes from one day to another; in this sense, the continuation of the inflationary spiral can have no other outcome than the paralysis of the world market.

In general, to the extent that it is speculation which is in large part responsible for the 1972-73 recovery, we are now back in a situation where:

- the purchases which enterprises should now be making have already been made;

- and where these purchases are manifested in a strengthening of productive capacity.

This means that the inflationary spiral and mini-recovery of 1972-73 can only lead to a new recession in comparison to which that of 1971 will seem like a picnic.

More than ever, then, the perspective is one which we drew up in our previous article:

- a massive slowdown in international trade;

- trade wars between different countries;

- imposition of protectionist measures;

- the collapse of customs unions;

- return to autarky;

- fall in production

- massive growth in unemployment;

- decline in real wages of workers.

The crisis and the tasks of the proletariat

This study of the current economic situation has not been embarked on for any academic reasons but solely as a basis for militant revolutionary activity. Such arguments as ‘it is useless to be concerned with the economic situation since in any case we can’t do anything about it’, or ‘what is important is the action of revolutionaries’, are totally irresponsible.

The economy is the skeleton of society, the basis of all social relations. In this sense, for revolutionaries, to know the society they are fighting against and how it is to be overthrown, means in the first place to know its economy. It is because of its specific place in the economy that the proletariat is the revolutionary class and it is from the precise economic conditions of crisis that the proletariat is to accomplish its historic task. It is always by beginning from an understanding of the economic conditions from which the struggle of their class derives that revolutionaries have attempted to clarify their objectives and perspectives.

In this sense, the two subjects dealt with in this article – inflation and the crisis of overproduction – enable us to situate the contemporary tasks of the proletariat.

Inflation is the expression of the historic crisis of the capitalist mode of production, a crisis which threatens the basic functioning of the system and the whole of society. Consequently, its very existence as a chronic illness of our epoch means that what is historically on the agenda today for the proletariat is no longer the amelioration of its condition within the system but the overthrow of the system.

As for the recession which is emerging today, to the extent that it plunges the system into growing contradictions and therefore into a position of weakness, it indicates that this overthrow is possible within the present period.

In the years ahead, the economic crisis will force the workers to engage in harder and harder struggles. Faced with this, capital will bring out the whole panoply of its mystifications and, in particular, will try to explain that ‘the former leaders are responsible for the crisis’ or that ‘with better management the situation could improve…’ Already forces whose aim is to reorganise capital are preparing for battle: in France the left throws itself into a mighty campaigns ‘against the high cost of living’, supported by other leftists who have no qualms in shrieking, “government and bosses are organizing ‘la vie chere’” (16)

Against these kind of demagogic phrases revolutionaries must affirm that, on the contrary, the bourgeoisie is hardly in control of anything at all, that it is faced with a situation about which it can do less and less – except to try to mystify the workers the better to massacre them afterwards.

If revolutionaries have one fundamental task today, it is to explain that the present crisis has no solution, that it cannot be overcome by any reform of capital, and that, consequently, there is only one way out: that of the communist revolution – of the destruction of capital, of wage labour and the commodity economy.

CG

Footnotes:

- For a deeper study, see ‘The Crisis’, R.I. no. 6 and 7, old series.

- Christian Goux’s article in Les Informations, a bosses’ journal.

- Such as those who consider that “revolutionaries who have only too often founded their hopes on the perspective – presented as the foundation stone of Marxism – of an inevitable catastrophe of the capitalist economy, seem today to be chimerical spirits locked up in anachronistic dreams” (Organise the revolutionary Marxist tendency, a pamphlet edited by the predecessors of today’s Gauche Marxiste, now defunct).

- The dramatic falls in Wall Street in August ’71, July ’73 and November ’73 cannot be compared to the catastrophic ‘Black Thursday’ of 1929.

- Today, the dollars circulating the world are hardly covered even for a few percent by gold or foreign currencies.

- This is not necessarily true if the parity of currency A is fixed in relation to the others (as was the case up to the last few years with the major currencies) but, otherwise, to maintain a currency at an over-valued level leads to unbridled speculation against it. This means that a central bank of country A gets rid of all the paper money which it has itself made, which can buy very little and which no one wants. Such a situation could only be bought to an end by a draconian control of exchange which would be virtually impossible to implement, or by a devaluation having a double function: that of lowering the price of that country’s commodities on the world market, and of discouraging speculators who henceforth would sell their currency A at a lower price.

- ‘La Crise’, R.I. nos 6 and 7, old series.

- The lining up of Giscard with the Americans at the Tokyo conference which opened the Nixon Round at the International Monetary Fund meeting in Nairobi, after he’d been screaming at the top of his voice that there could be no question of submitting to these conditions, is particularly significant in this respect.

- Philippe Simonot, Le Monde, 13th Feb, 1973, p.2.

- The bourgeoisie is certainly more lucid than certain contemporary ‘Marxists’, great critics of the ‘wretched readers of Marx’, who claim that, “the source of the difficulties of capitalism’s functioning resides at the level of production and not of the market” (Lutte de Classe, organ of Groupe de Liaison Pour L’Action des Travailleurs (GLAT), Sept/Oct. 1973). As if one could separate the two and as if capitalist production was not the production of commodities! Marx was certainly one of the ‘wretched readers of Marx’ when he wrote: ”All the contradictions of bourgeois production break out together in the generalized crises of the world market … Overproduction is a particular consequence of the general law of capitalist production: to produce in proportion to the productive forces … without taking account of the limits of the market nor of effective demand…” (Marx, La Pleiade T.2. p.496).

- It should be noted that these two interpretations are not contradictory and that most economists use them simultaneously: their only fault is that they don’t explain anything.

- We shall see elsewhere that this scarcity itself can only be understood within the context of today’s overproduction.

- It is obvious that the increase of 10% given to the French workers in May ’68 is in part responsible for the price rises which followed.

- One recalls the merciless war which the airline companies are waging over transatlantic air fares, a war which followed a period of peace and which led to a new status quo, when these companies found themselves back at the edge of bankruptcy.

- See the articles on ‘The Decadence of Capitalism’ in R.I. no. 2,4 and 5 (new series, shortly to be a W.R./Internationalism pamphlet.

- Lutte Ouvrière, no. 272.

Rubric:

Sudan 2023: a vivid illustration of the decomposition of capitalism

- 255 reads

The horror show of imperialist war unfolding in Sudan is a continuation and extension of the decomposition of capitalism, which has been visibly accelerating since the beginning of the 2020s[1] [5]. It expresses the profound centrifugal tendency towards irrational and militaristic chaos that will affect more and more regions of the planet. Whatever the specifics of the two military gangs fighting in Sudan – and we look at these a bit closer below – the major culprit in this latest outbreak of war is the capitalist system and its representatives in the major powers: USA, China, Russia, Britain, followed by all the secondary powers active in Sudan: the UAE, Saudi, Turkey, Israel, Egypt, Libya, etc. Towards the end of last year, December 5, the British Foreign Office released a statement on the democratic future of Sudan which began thus: “Members of the Quad and Troika (Norway, the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, the United Kingdom, and the United States) welcome the agreement of an initial political framework. This is an essential first step toward establishing a civilian-led government and defining constitutional arrangements to guide Sudan through a transitional period culminating in elections. We commend the parties’ efforts to garner support for this framework agreement from a broad range of Sudanese actors and their call for continued, inclusive dialogue on all issues of concern and cooperation to build the future of Sudan.”[2] [6] Just weeks before heavy fighting broke out on April 8, the above “international partners” of Sudan were still talking about an “imminent return” to civilian rule and a democratic government involving the two main components of the Sudanese government: the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) led by General Abdel Fatah al-Burham and the Rapid Strike Force (RSF)[3] [7] led by General Hamdam Dagalo aka “Hemediti”. It was abundantly clear just days after the fighting between these two Sudanese military factions began, that this “democracy” – just as anywhere else – is an illusion and all of the immediate options and longer-term perspectives for the population of Sudan and the surrounding region are going to go from bad to much worse This is exemplified in Sudan with its capital, the relatively peaceful and bustling Khartoum, previously spared the horrors around it and filled with refugees from the 2003 “Darfur conflict” (i.e., ethnic genocide[4] [8]) onwards, is now being reduced to ruins in a matter of days. Lack of water, electricity, health services is accompanied by slaughter and rape from both sides of the ex-government forces.

The “inner disintegration” of capitalism

In 1919, the Communist International laid out its future perspectives for capitalism: "A new epoch is born! The epoch of the dissolution of capitalism, of its inner disintegration. The epoch of the communist revolution of the proletariat”[5] [9]. The reality of this epoch of capitalism has been confirmed by over a century of ever-growing imperialist war, its only answer to its permanent economic crisis. We have now been through over 30 years in the final phase of this process of capitalist decadence, the phase of decomposition. And since the Covid pandemic and even more with the war in Ukraine we are seeing a tragic acceleration. The profound putrefaction of this mode of production can be today measured by a veritable spiral of destruction on a global scale, and in particular through the multiplication of wars and massacres (Ukraine, Myanmar, Yemen, Tigray...). In Sudan today we can see the breakdown of the “international community’s peace process”; of the Sudanese state and the military government of Sudan, immediately demonstrating a wider tendency for these agents of the major powers to function as unreliable, irrational elements that are first of all motivated by “look after number one”: this is demonstrated by the Russian Wagner Group[6] [10] (active in Sudan, Chad and Libya under General Khalifa Haftar) which seems to be increasingly falling out with Moscow and taking on a dynamic of its own. And this tendency of each for themselves is further underlined by the fact that any one of the countries mentioned in the first paragraph is quite capable of taking their own unilateral actions that will further exacerbate the tendencies to further chaos in Sudan and the surrounding region.

“Save our nationals”... and the devil take the hindmost

Sudan was a British Crown Colony until 1956 when the US undermined the role of British imperialism in the wake of the Suez crisis As in many of its colonies the British had introduced the practice of divide and rule, using ethnic and geographic divisions in order to facilitate control. The long-term consequences of this policy could be seen in 2011 when the country was cut in half between an Arab-dominated North and an African South. Sudan, full of natural resources, is adjacent to the Red Sea, borders Egypt and Libya in north Africa; Ethiopia and Eritrea in the Horn; the east African state of South Sudan and the Central African states of Chad and the Central African Republic. It is thus a focus for all the regional and global imperialist rivalries which are being played out across Africa and the Middle East.

With the outbreak of the present conflict, the main concern of the hypocritical “partners” of Sudan was first to get their diplomats and then their nationals out of the country, burning and shredding evidence of their murderous culpability as they did so. Echoing capitalism’s “war of the vaccines” during the Covid-19 pandemic, we witnessed the scrabble of “each for themselves” as competitive “national interests” overrode any sort of co-operation; flights left half-empty because the necessary papers weren’t shown or they weren’t on the list of nationals of those controlling the flights. When other nationals were given places on evacuation procedures it was done as a cynical PR exercise or to gain some sordid diplomatic advantage. And what those fleeing powers left behind was a complete mess of their own making and a grim future for the region.

It’s pointless quoting numbers of casualties or the destruction caused because the “official” figures are increasing exponentially every few days: tens of thousands killed and seriously injured and millions of refugees and displaced, with around 15 million already living on the scraps of the aid agencies (themselves an integral part of imperialism and warfare) and acute malnourishment among pregnant women and children, according to a UN statement on April 11. Those nationals lucky enough to get back to were met with flags and jingoistic press headlines while the vast majority in Sudan have no way out of war and famine and are condemned to their misery by the same flag-waving national interests of the capitalist states that came to bring “democracy” to the country.

To add to the whole mess of Khartoum and beyond, around 20,000 prisoners have escaped or been let out of jail with some of these being convicted ex-government mass murderers and war criminals who, in their respective sides, will be welcomed back into the free-for-all at even more cost to the population and its forlorn hopes for any sort of “peace”. As well as staggering inflation, the organised looting of supplies, assaults and robberies by armed militias, the population has to deal with the ubiquitous and dangerous checkpoints that have sprung up on many streets. And to add to their emotional turmoil, cease-fires and truces are called one after the other making no difference whatsoever to the ongoing warfare[7] [11].

The decomposition of capitalism guarantees the military free-for-all

The two major warlords, Generals Dagalo and Hemediti, the west’s “democratic partners” and Moscow’s “friends and allies”, are locked into a ferocious battle between each other with the SAF having the advantage of air power. It’s not a great advantage in this sort of war but if the battle is to continue both sides will need re-supplying with weaponry soon: will the Russians supply the RSF with anti-aircraft missiles or more through Wagner? Will Russian-backed Haftar of Libya step up the supplies and support he is and has been providing for the RSF? Will Saudi and Egypt get more involved in stepping up the ante with weaponry to the SAF, and are Abu Dhabi and Riyadh at loggerheads over the issue? And will the backers of the RSF in the UAE – who see the former as part of their wider plan for control over the Red Sea and the Horn of Africa – consolidate and strengthen their support? Could Britain and America get further involved through some of these vectors? Given the deep instability of the situation and all the players involved, there are too many uncertainties to make any sort of predictions - except that the war will continue and the overall framework of decomposing capitalism will ensure that it will become more extensive.

China is well involved in Sudan and in machinations with both factions of the army in order to maintain its “Belt and Road” thrust which has come to grief in neighbouring Ethiopia. The US is playing catch-up with China but President Biden has recently stepped up US military activity here with extra military resources deployed in order to “fight terrorism”. But there’s no doubt it has been flatfooted in its response and embarrassed with its and the UK’s assertion that we were days away from “civilian rule” in Sudan. Russia has also dealt with both factions of the army and both have talked favourably about a possible Russian port on the Red Sea. Both factions are open to a deal with Russia but the whole region now resembles a highly volatile can of worms.

The Sudanese evacuations are largely over to date and true to form the war is cynically relegated away from the headlines as the country sinks back into an even greater misery. Sudan is one example of capitalism’s dynamic and there are many others: dangerous imperialist fault-lines are opening up with military tensions rising in the Middle East, around ex-Yugoslavia and the Caucasus and generally over the globe as militarism is the main outlet left to the capitalist state. The war in Ukraine with its local and global effects rages on. In early April this year, Finland became the 31st country to join NATO and its 1300km border has doubled the front line with Russia. As it has done in other front-line states with Russia, NATO will be cautious at first and then build up its forces and weaponry along the border, forcing Russia to militarise its side.

The longer-term perspective for imperialism is the growing confrontation with China being prepared by the United States, but there are uncertainties and variables here also. In the meantime capitalism sinks into irrational war and barbarity and Sudan is one more example of its “inner disintegration”.

Baboon, 3.5.2023

[3] [16] The RSF has its roots in the dreaded Jangaweed militia, an Arab-based killing and raping military machine that became part of the Sudanese government after the ousting of dictator Omar al-Bashir in 2019. The Jangaweed was a product of imperialism in the 1980’s and was integrated into Sudan’s government under its intelligence services with the support of the west.

[4] [17] It is very likely that this “ethnic cleansing” element – a growing factor of decomposing capitalism everywhere – will again resume with full force in Darfur where it hasn’t really stopped for years.

[5] [18] Platform of the Communist International, https://www.marxists.org/history/international/comintern/1st-congress/pl... [19]

[6] [20] The Russian Wagner Group has dealt directly with both Sudanese military factions, reportedly since 2018, and has been active around the Port of Sudan with British intelligence stating that it is a “big hub” for them (quoted in The Eye newspaper, April 29); also that the Group is aiming “to establish a ‘confederation’ of anti-Western states”. Apart from some training and activity in Sudan and around the region, and its close involvement with Field Marshal Khalifa Haftar of Libya, the Group has also been involved, through its “M Invest, Meroe Gold” front established by Moscow and the Sudanese dictator Bashir, in sending volumes of the precious metal out of the country.

[7] [21] During the war in Lebanon from 1975 to 1990, thousands of cease-fires were called and ignored. Lebanon was something of a “template” for the onset of capitalist decomposition and the appearance of “failed states”. To date Lebanon has been joined by Yemen, Syria, Afghanistan, Libya and now Sudan (with Pakistan not far above the relegation zone). These regions have virtually no possibility of any effective reconstruction under capitalism.

Rubric:

Argentina: the crisis is hitting the workers

- 75 reads

Faced with the constant attacks on their living conditions, the Argentinean working class is responding with a growing fighting spirit. The bourgeoisie in Argentina is preparing for the possibility of a wave of strikes in different sectors. That is why the government with the support of the unions is taking immediate measures to contain the anger in response to the deteriorating conditions – to the precariousness and the effects of globally rising inflation. Though offering wage increases by instalments has become very fashionable right now, this will not compensate for the loss of purchasing power due to inflation in all the countries of the world, including Argentina.

Argentina is currently the country with the second highest inflation in the region after Venezuela. By the end of 2022 the rate of inflation had reached 94%, the highest since 1991. The economic consequences of the war in Ukraine1 following the covid pandemic have been severe. Inflation has caused a deterioration in the material conditions of the population but this deterioration has become much worse for the working class in all countries. Inflation is eroding the purchasing power of workers while wages remain static. It is not by chance that on 26 August last year, the Argentine government has announced a 21% increase in the minimum wage in three stages, rising from 47,850 pesos per month (around 200 euros) to 57,900 pesos (243 euros) in November this year2.

Faced with the capitalist crisis that has hit Argentina, there have been many struggles in recent months, such as that of the workers of the Bridgestone, Fate and Pirelli tyre companies, which paralysed the Argentine car industry for several months, affecting the production of these factories. After lengthy negotiations between the Sutna (United Tyre Workers) union, the companies and the government, an agreement was reached to increase the wages of Sutna-affiliated workers[1]. The wage increase will be in instalments, with the additional promise from the companies to also give each worker a one-off bonus to of 100,000 pesos (about 421 euros).

The parties, unions, the Piqueteros and the government are all against the working class

Like the struggles of the workers in the tyre industry, there are other struggles that have been taking place since before the pandemic that have been stifled and controlled by the parties, unions, Piqueteros and the government, illustrating how they all act in a coordinated way against the workers.

At the beginning of 2022, the German press agency DW (Deutsche Welle) said: "The president of Argentina, Alberto Fernandez, announced this Friday (28.01.2022) that an ‘agreement’ was reached with the International Monetary Fund (IMF) to refinance the loan of more than 44 million that the IMF gave the country in 2018 when the liberal Mauricio Macri was head of government"[2].

Anticipating and pre-empting this announcement at the beginning of January 2022, Eduardo Belliboni, leader of Polo Obrero and head of the Unidad Piquetera, already announced that 2022 will be much more eventful than 2021. And so it happened. "The greatest mobilisation of demands against the government of Alberto Fernández", called the "Federal March", was prepared by organisations and social movements (Coordinadora por el Cambio Social, Polo Obrero (PO), Movimiento Barrios de Pie (MBP), etc., those grouped together in the Unidad Piquetera. The mobilisation, which emerged in different states, began on 10 May 2022 in the cities of La Quiaca and Ushuaia and ended on 12 May in the capital Buenos Aires.

The marchers voiced slogans such as: "For work and for wages; against hunger and poverty". Eduardo Belliboni, said "The Federal March of the Piqueteros is becoming a march of the working people against the falling wages and for their own demands. It is uniting unemployed, employed and retired workers behind the leadership of the main trade unions. A prospect of unity and struggle is opening up for the popular movement, in support of the basic demands of the working class suffering from the government's agreement with the IMF...We are demanding real jobs and a wage that will be enough to feed a family and allow us to live. We are marching against hunger and poverty that has reached scandalous levels in Argentina".

The demonstration arose in response to the government's decision not to extend further the "Promote Access to Employment" programme to those people in desperate need. Currently there are around 1,200,000 people receiving 19,470 pesos per month (equivalent to around 85 euros).

These protests are taking place at a time when we are seeing a new development unfolding in Argentina, with the various bourgeois factions clashing more and more openly with each other in the run-up to the parliamentary elections in November. The bourgeois factions that defend Peronism within the “Casa Rosada” are divided into those who continue to support “Kirshnerism” and others around Fernández, a struggle that has been going on for years. The presidential couple have not spoken to each other for two months and openly insult each other. The spokespersons of the former president call Fernández a usurper of the throne and remind her that she is in this position on a temporary basis. "The government is ours" warned Andrés Larroque, minister in the province of Buenos Aires and strongman of La Cámpora, the group led by Máximo Kirchner, Cristina's son. Fernández replied herself saying that "Nobody owns the government, the government belongs to the people".

On the eve of these November elections the struggle for power is increasing between the different bourgeois factions, the Peronists, the centre moderates, the right-wing around Macri alongside the emergence of a “psychedelic” nationalist populist and self-styled "libertarian", like Javier Milei, who presents himself as anti-socialist, anti-communist, anti-Peronist, anti-traditional political parties, and openly claims to be a staunch admirer of Trump and Bolsonaro.

We have been reporting on the Piquetero movement: for some time:“Between June and August (2005) we have seen the biggest wave of strikes for 15 years”. We have reported that the Argentine proletariat was showing itself to be combative, fighting on its class terrain and showing a capacity to recognise itself as a class with its own class identity. In the same article we analysed and outlined how these workers' struggles, on a difficult road to recovery, were still very weak and were overshadowed by "...a noisy and hyper-exposed media confrontation between the Piquetero organisations and the government”[3].

The Piqueteros, a movement mainly comprised of the unemployed, arose within the interclass struggles of late 2001, and acquired great notoriety due to the mass media which propelled them into the political limelight as the true standard-bearers of the "legitimate struggles" of the people seeking improvements in their living conditions. All the leftist groups, Stalinists, Trotskyists, Maoists, etc, collaborators in the mystification of the workers' struggles, allied themselves with the bourgeois state to give the piqueteros a pseudo-revolutionary support, which deceived and confused the unemployed workers and those impoverished sectors of society even more, diverting them into the dead end of democracy and parliamentary elections, support for one or other messiah of the bourgeoisie, like the way Mr. Kirshner was presented at that time[4].