The Struggle for the Class Party in Britain 1848-1914

- 384 reads

Without a revolutionary party, there cannot be a successful revolution. And while the fight for the party is always posed at an international level, and the fundamental problems encountered in the fight are both universal and historic, stemming from the proletariat's position as an exploited class confronted with the immense weight of ruling class ideology, it is also important for revolutionaries to examine the specific conditions - both historical and geographical - in which this fight takes place. Thus, revolutionaries in Britain are faced with a weakness in the marxist tradition, and a strength of reformist illusions, which go back a long way, and which have made the struggle for the class party in this country a particularly arduous one. The series of articles we begin here, which was first published in World Revolution from October 1996 to September 2000, while not pretending to be an exhaustive treatment of the problem, aims to provide a framework for understanding these difficulties. In particular, it will show why the formation of the Labour Party at the beginning of the 20th century failed to answer the needs of the workers' movement for a revolutionary party.

Rubric:

Part 1: From Chartism to the Socialist League

- 120 reads

The development of the organisation of the working class

In the Inaugural Address of the International Workingmen's Association in 1864, Marx wrote of the working class "One element of success they possess - numbers; but numbers weigh only in the balance, if united by combination and led by knowledge". In this he summarised the fundamental requirements for the success of the proletariat's struggle. The primary task of the working class was stated equally succinctly: "To conquer political power has ... become the great duty of the working classes" (Inaugural Address).

From the time of its origin the proletariat struggled to defend its interests, initially in dispersed outbursts, but increasingly realising its strength through combination in unions and political organisations. This was its first task and was also the fundamental objective of the First International, within whose ranks many varied and opposing organisations took their place (see “The First International and the fight against sectarianism [2]”, International Review 84).

In the latter part of the century a very different situation arose. The economy grew with a vigour unseen before and the bourgeoisie grew richer. This situation tended to favour the struggle of the proletariat and it saw real improvements in its living conditions and political rights: "The proletariat affirmed itself as a social force within society, even outside moments of open struggle. The working class had a life of its own within society: there were the trade unions (which were 'schools of communism'), but also clubs where workers talked politics and 'workers' universities', where one might learn marxism as well as how to read and write (Rosa Luxemburg and Pannekoek were both teachers in the German social democracy); there were working class songs, and working class fetes where one sang, danced and talked of communism" (International Review 50 “Continuity of the proletariat's political organisations: The class nature of social democracy [3]”).

The social democratic parties and the trade unions were "the products and the instruments of the combats of this period" (ibid). Social democracy "only developed and organised a real movement that had existed well before it, and developed independently of it" (ibid). Thus the activity of the social democratic parties did not constitute a concession to the bourgeoisie, even if reformist tendencies emerged, but rather the activity necessary for the proletariat in this stage of its struggle (for a fuller account see the article in IR 50 quoted above). Practically, the strategy of the working class was expressed in the concept of the 'minimum' and 'maximum' programmes, the link between which Rosa Luxemburg explained: " ... the proletariat, through its experience of the trade union and political struggle, arrives at the conviction that its situation cannot be transformed from top to bottom by means of this struggle, and that the seizure of power is unavoidable" (quoted ibid).

Britain: birthplace of the working class movement

To what extent does the situation that existed in Britain fit in with the framework we have sketched?

Britain's position as the first industrial country gave it an economic advantage that lasted many decades. It also made it the birthplace of the workers' movement and, most importantly, of what Marx and Engels described as the first political party of the working class: Chartism. The Chartists represented the first conscious attempt by the working class to assert itself on the political terrain. They saw the struggle for universal suffrage as a means through which the working class could come to power, which was an expression of the immaturity of the struggle at that stage. However, Chartism was effectively finished after 1848 and, while the unions remained strong in Britain, they increasingly tended to turn towards reformism and did not spread far beyond the skilled workers. No independent political organisation arose to take the place of the Chartists and the working class movement became, in Engels' famous phrase, "the tail of the 'Great liberal Party'" ("A Working Men's Party", Collected works vol.24), its leaders "rascals", "in the pay of the bourgeoisie" (Engels to Sorge and Engels to Wilhelm Liebknecht, Collected Works Vol.45).

The revival of the workers' movement

"After the cyclical crises of growth which had hit the system about every ten years between 1825 and 1873, for almost 30 years until 1900 capitalism experienced an almost interrupted prosperity" (IR 50). However, within this prosperity there were signs of major changes in the economy, notably in Britain where a slowdown of growth led to difficulties for the capitalists and hardship for parts of the working class. Engels traced this in some detail and concluded that Britain's industrial monopoly was ending with serious consequences for the working class. However, within this, he also perceived the development of conditions which would require the working class to take up the work of its Chartist forebears: "The truth is this: during the period of England's industrial monopoly the English working class have to a certain extent shared in the benefits of the monopoly. These benefits were very unequally parcelled out amongst them; the privileged minority pocketed most, but even the great mass had at least a temporary share now and then. And that is the reason why since the dying-out of Owenism there has been no socialism in England. With the breakdown of that monopoly the English working class will lose that privileged position; it will find itself generally - the privileged and leading minority not excepted - on a level with its fellow workers abroad. And that is the reason why there will be Socialism again in England" (“England in 1845 and 1885”, Collected Works Vol.26). Engels sought to influence this revival with a series of articles in the Labour Standard in which he defended the importance of the unions, but also showed their limitations and argued for the creation of an independent working class party. A decade later, after watching the May Day celebration in London, he declared "on May 4, 1890, the English proletariat, rousing itself from forty years of hibernation, rejoined the movement of its class" (“May 4 in London”, Collected Works Vol.27).

New Unionism

The fundamental reason for this change lay in a resurgence of class struggle, marked especially by a series of successful strikes amongst unskilled workers. These strikes succeeded not only in increasing pay but also in significantly reducing the length of the working day. Engels attached particular importance to the participation of the workers of London's East End in these strikes: "If these downtrodden men, the dregs of the proletariat, these odds and ends of all trades, fighting every morning at the dock gates for an engagement, if they can combine and terrify by their resolution the mighty Dock Companies, truly then we need not despair of any section of the working class" (“Apropos of the London Dockers' Strike”, Collected Works Vol.26).

The New Unions that these workers created to wage their battles were heavily influenced by socialists like Eleanor Marx and Edward Aveling and by members of the Social Democratic Federation such as Will Thorne and, as such, differed markedly from the old unions of skilled workers whose leaders were still tied to the Liberal Party.

The first marxist organisation: the SDF

At the start of the 1880s no significant revolutionary organisations existed in Britain. A few survivors of Chartism and Owenism continued to meet, small local groups of socialists came and went, while in London exiled revolutionaries from Germany and Austria regrouped and even managed to publish a weekly journal, Freiheit.

In 1881 a meeting of various radical groups, led to the foundation of the Democratic Federation under the direction of Henry Meyers Hyndman, who considered himself to be a socialist. The Federation gradually expanded and drew in new members, such as William Morris, Edward Aveling, Eleanor Marx and Ernest Belfort Box who sought to push it further towards socialism. In 1884 these efforts led to the federation being renamed as the Social Democratic Federation.

The programme of the Federation called for "The socialisation of the Means of production, Distribution and Exchange, to be controlled by a democratic state in the interests of the entire community, and the complete Emancipation of Labour from the domination of Capitalism and Landlordism, with the establishment of Social and Economic Equality between the sexes". Particular points called for reforms in working hours, in the employment of children, for free education and for a citizen army. A weekly newspaper, Justice, was launched and weekly public meetings held. Engels saw the former as opportunist, launched with neither sufficient financial or literary preparation and written by people "who take in hand the task of instructing the world about matters of which they themselves are ignorant..." (Engels to Laura Lafargue, Feb. 1884, Collected Works Vol.47). Above all Engels criticised the SDF for failing to understand or relate to the working class. This was exemplified in Hyndman's attitude to trade unions and strikes which he described as "varying forms of restless working class ignorance, or despairing revolts against endurable oppression... [which] do but serve to rivet the chains of economic slavery, possibly a trifle gilded, more firmly on their limbs" (quoted in F.J. Gould, Hyndman: Prophet of Socialism). That there is no recognition of the role of the trade unions in developing the consciousness and self organisation of the working class, which Engels had set out in the articles in the Labour Standard, reflects Hyndman's conception of the working class as an inert mass which might respond to events but which required the guidance of leaders like himself to achieve anything constructive. This was to be accomplished through propaganda and, above all, participation in elections.

Hyndman: an adventurer in the workers' movement

If other socialists of the time shared his schematism, Hyndman's efforts to manipulate the workers' movement to further his own career and, above all, to realise his place in history as 'the father of British socialism', marked him out as an adventurer.

Hyndman had previously been an entrepreneur, engaging in journalism in Australia, tourism in Polynesia and financial speculation in America. At the start of 1880 he was in Britain looking for a foothold in politics, promoting a `Tory-Radical' revival to Disraeli and standing as an independent Tory in the election of March that year, during which he declared his opposition to Irish home rule, his support for the colonies (“the special heritage of our working class” - Quoted in E.P. Thompson, William Morris: Romantic to Revolutionary) and for an increase in the size of the navy. He became 'converted' to marxism after reading Marx's Capital on a voyage to America following the failure of these efforts. On his return, he sought out Marx and, in Marx's words, "intruded himself into my house" (Marx to Sorge, December 1881, Collected Works Vol.46). At the launch of the Democratic Federation, the platform of the organisation, entitled "England for All" and written by Hyndman, was distributed to all the participants. Large parts of this were lifted from Capital without Marx's knowledge or consent and contained errors and imprecisions. Faced with Marx's criticism, Hyndman excused himself on the grounds that "Englishmen have a dread of being taught by a foreigner" and that "many have an horror of Socialism and that name" (Marx to Hyndman, July 1881, Collected Works Vol.46). Rebuffed by Marx, Hyndman tried to cultivate Engels, but the latter refused to have any contact until the situation with Marx had been settled and subsequently remained strongly critical of Hyndman. This attitude is often presented as one of personal animosity, stemming from Engels' defence of his friend. In reality it stemmed from a political analysis that both Marx and Engels shared. Marx summed up his view in the letter to Sorge we have already quoted: "All these amiable middle-class writers...have an itching to make money or name or political capital immediately out of any new thoughts they may have got at by any favourable windfall. Many evenings this fellow has pilfered from me, in order to take me out and learn in the easiest way". Engels, with the benefit of further knowledge in the ensuing years, was able to identify Hyndman quite precisely as a careerist and an adventurer (Engels to Bernstein, Dec. 1884, Collected Works Vol.47).

The birth of the Socialist League

From the outset there were tensions within the SDF, stemming largely from Hyndman's dictatorial manner, but also from differences over policy, particularly the exclusive focus on parliament and Hyndman's continuing nationalism.

The tensions broke into open struggle when Hyndman's manoeuvres in Scotland were uncovered. These included attempts to defame Andreas Scheu, one of Hyndman's most implacable opponents, and the sending of letters in the name of the Executive which were not sanctioned by the Executive and which actually went against its decisions. Hyndman also circulated gossip that Eleanor Marx and Laura Lafargue (Marx's second daughter) had plotted against him. At a meeting of the Executive the evidence against Hyndman was presented and a motion of censure was passed. The majority, which included Morris, Aveling, Eleanor Marx and Bax, then resigned from the Executive to form the Socialist League, stating that "since it seems to us impossible to heal this discord, we ... think it better in the interests of Socialism to cease to belong to the council" (Quoted, Thompson, op.cit). Engels gave two further reasons: the possibility that Hyndman would reverse the decision at a subsequent conference by packing it with fictitious delegates and "because the entire Federation was, after all, no better than a racket". However, the consequence was that Hyndman was left secure on the Executive and in control of the paper and all the branches of the SDF.

This placed the Socialist League in a weak position from the outset, but nonetheless it marked a significant advance on the SDF in a number of areas:

- it rejected all nationalism and Jingoism, declaring firmly the necessity of internationalism: "The Socialist League ... aims at the realisation of complete Revolutionary Socialism, and well knows that this can never happen in any one country without the help of the workers of all civilization" (Manifesto of the Socialist League, in: Thompson, op.cit);

- it defended the active, conscious, participation of the working class in the revolution: "Discontent is not enough ... The discontented must know what they are aiming at_ [it] should be, not an ignorant, but an intelligent revolution" (William Morris, quoted Thompson op.cit);

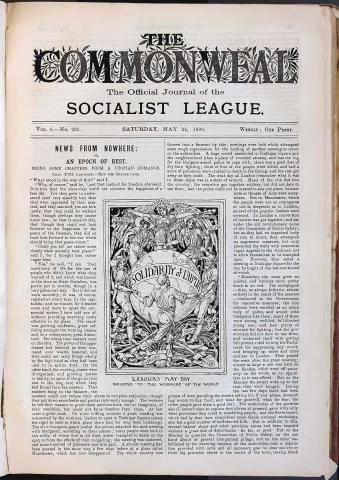

- it took a more realistic view of the work ahead, publishing its paper, The Commonweal, monthly rather weekly: "At last they are going to operate modestly and in accordance with their powers, and not go on pretending that the English proletariat must instantly jump to it the moment the trumpet is sounded by a few literary converts to socialism" (Engels to Bernstein, Dec.1884, Collected Works Vo1.47).

However, the League was also marked by some important weaknesses, that sprang essentially from its failure to link the struggle for the revolution to the immediate demands of the working class. This had been the case with the SDF but, if anything, the Socialist League went further, eventually rejecting all reforms, and particularly participation in elections, in the name of a pure, untainted, revolution. In part this can be attributed to the disgust of the founders at the manoeuvres of Hyndman but, more fundamentally it reflected their isolation and lack of understanding of the working class. Engels pointed to this when he described Aveling, Bax and Morris as "three as unpractical men - two poets and a philosopher -as it is possible to find" (ibid).

The second part will look at the development of the SDF and the Socialist League in the late 1880s and their relationship to the wider working class movement.

North

First published in World Revolution 198 (October 1996)

Rubric:

Part 2: The role of the Social Democratic Federation

- 88 reads

In the first part of this occasional series (World Revolution 198) we examined the gradual revival of the workers movement in Britain in the early 1880s. We sought to place this in both the general context of the development of the international proletarian movement and the specific conditions prevailing in Britain.

The objective conditions for such a revival, as Engels showed, developed during the 1880s and manifested themselves in an upsurge of class struggle, particularly towards the end of the decade. However, the development of the subjective conditions, the creation of a proletarian organisation able to rally and lead the working class, proved much more difficult. Our article traced the emergence of the Social Democratic Federation in 1884 under the leadership of the adventurer Hyndman and showed how he manoeuvred to build up his position and to defeat those who opposed his dictatorial rule and jingoist attitudes. We ended with the secession of William Morris, Belfort Bax, Eleanor Marx and Edward Aveling to found the Socialist League at the end of 1884.

We will return to the evolution of the Socialist League in a subsequent part of the series, but in the present article we look more closely at the practice of the SDF in the second half of the 1880s and show how, under the direction of Hyndman, it worked time and again against the development of the working class movement, by strengthening the tendencies towards sectarianism and isolation and by discrediting socialism in the eyes of the working class.

What kind of organisation?

To understand the role played by the SDF, and Hyndman's faction particularly, it is necessary to begin by considering what sort of organisation the proletariat required to defend itself and advance its interests in the late 19th century. These are the criteria against which the role of the SDF must be judged.

The rapid development of capitalism in this period confronted the proletariat with a bourgeoisie that was tending to become stronger and more unified. To struggle effectively, the working class was required to reply in kind, forging an instrument with a clear programmatic and organisational basis, which recognised the link between the class's immediate struggles and its long term goal and which, crucially, saw itself as part of an international movement.

The Social Democratic parties and, above all, the Second International, were the proletariat's answer. These organisations were not imposed from outside the class as the bourgeoisie like to pretend but "only developed and organised a real movement that had existed well before it and developed independently of it. Then, as today, the question has always been the same: how to fight the situation of exploitation in which it finds itself” (International Review 50, “Continuity of the proletariat's political organisations: The class nature of the Social Democracy [3]”). Social Democracy was a weapon created by the proletariat to wage its struggles. It marked a crucial advance over the past in its adherence to marxism and rejection of anarchism, in the distinction it made between the unitary and political organisations of the class and in the setting out of the minimum and maximum programmes.

These gains did not arise spontaneously but were the fruit of hard and prolonged struggles within the workers movement, in which the main responsibility fell repeatedly to the left wing of the movement, first to win the advances and then to defend them against the forces of compromise and reformism which were stimulated by the seemingly limitless advance of capitalism and the reforms that this advance made possible.

The 1885 election: discrediting socialism

The British election of 1885 was the first since the Reform Act of 1884 which, while stopping far short of universal suffrage, considerably extended the vote and, in Engels' view, made it likely that a number of official labour leaders would get elected with the support of the Liberals. Engels felt that this would aid the development of the independent workers movement since these leaders would "quickly show themselves up for what they are" (Engels to Bebel, October 1885, Collected Works Vol.47).

The SDF put up three candidates, two in London and one in Nottingham. The expenses of those in London were paid for by the Tory Party following an agreement reached by Hyndman's clique behind the backs of the body of the SDF. The candidates were deliberately located in strong Liberal constituencies where they were doomed to fail and on polling day they received just 59 votes between them. When news of the deal leaked out, the Liberal press mounted a virulent campaign denouncing the SDF for accepting 'Tory Gold' and for doing the Tory Party's dirty work. Hyndman and his followers claimed that it was irrelevant who they took money from, but in a letter to Bernstein, Engels spelt out the consequences of Hyndman's action: "Hyndman, however, knew that to take money from the Tories would spell nothing less than irreparable moral ruin for the socialists in the eyes of the one and only class from which they could draw recruits, namely the great radical working masses" (Collected Works, Vol.47). Consequently, the hold of the Liberals over the working class was strengthened and the creation of an independent organisation set back.

Engels' criticism, although not his analysis, was shared by the Socialist League, whose executive passed a resolution declaring "That this meeting views with indignation the action of certain members of the Social Democratic Federation in trafficking the honour of the Socialist Party, and it desires to express its sympathy with that section of the Federation which repudiates the tactics of the disreputable gang concerned in the recent proceedings" (Quoted in Lee and Archibold Social Democracy in Britain). One leading member of the League, Adreas Scheu, denounced Hyndman as "a paid agent of the Tories (or liberal-reactionists) for the purpose of bringing Socialism into discredit with the masses" (Quoted in Thompson William Morris: Romantic to Revolutionary).

Within the SDF itself, as the League's resolution noted, there was also strong criticism. One of the candidates claimed he had not been informed and wrote to the press denouncing the deal and "the middle class men of our movement" (quoted by Engels in a letter to Paul Lafargue, Collected Works Vol.47). Opposition was especially strong, amongst the provincial branches and, following the failure of an attempt to censure Hyndman at a meeting in London, a large number of militants resigned, including the entire Bristol and Nottingham branches.

Opposing strikes and promoting riots

Under Hyndman's influence, and despite the presence of a number of Trade Unionists, the SDF adopted a very critical, even hostile, attitude to the unions, telling workers that strikes were futile: "There is nothing in strikes themselves, whether for a rise of wages for all, or the enactment of a minimum wage for the lowest grades of labour in any industry, which can emancipate the propertyless workers or render them less dependent upon the owning and employing class... " (quoted in Gould Hyndman: Prophet of Socialism). In contrast, the SDF actively promoted marches and demonstrations of the unemployed, who were treated to revolutionary speeches and urged to pass unrealistic resolutions.

Shortly after the Tory Gold scandal, the SDF called a demonstration of the unemployed in Trafalgar square, nominally in opposition to a Tory 'Fair Trade' gathering in the same location. In reality, according to Karl Kautsky who observed the affair, the SDF demonstration was mainly composed of lumpen-proletarian elements, while most of the genuine workers were at the other meeting. After a number of 'revolutionary' speeches the SDF led their demonstration towards Hyde Park and as they passed through the wealthy streets of Pall Mall and Picadilly rioting broke out with windows smashed and shops ransacked. The SDF and, to a lesser extent, the Socialist League, saw the riot as positive. For the SDF it salvaged their 'revolutionary' credentials after the discredit of the Tory Gold scandal, while Morris commented that "any opposition to law and order is of use to us" (Thompson, op .cit.). Once again, it was Engels who grasped the real implications: "The absence of the police shows that the row was wanted, but that Hyndman and Co. fell into the trap is impardonable and brands them finally as not only helpless fools but also as scamps. They wanted to wash off the disgrace of their electoral manoeuvres and now they have done an irreparable damage to the movement here" (Engels to Laura Lafargue, Collected Works Vol.47). In a letter to Bebel he condemned the SDF for seeking to pre-empt the real development of the working class movement and compared them to anarchists. The ensuing trials for sedition against Hyndman and others were not seriously pursued and eventually came to nothing, but did much to increase Hyndman's standing amongst socialists and radicals.

The beginnings of a mass movement

Throughout 1886 and the winter of 1887 the SDF continued to orchestrate marches and demonstrations of the unemployed. These were frequently held outside London and were well organised. In the absence of any alternative, the SDF began to assume a leading role within parts of the working class.

In the first part of the year Engels had welcomed the lack of impact of the SDF and the Socialist League on the working class, but as the year passed he recognised the change in the situation. In August he wrote to Bebel "The Social Democratic Federation does at least have a programme and a certain amount of discipline, but no backing whatever from the masses" (Collected Works Vol.47). A month later he acknowledged that Hyndman had strengthened his position and by November was arguing that "Thanks to the stupidity of all its rivals and opponents, the Social Democratic Federation is beginning to become a power" (Engels to Laura Lafargue). This was manifested in further demonstrations of the unemployed in Trafalgar Square during that month, which this time passed off peacefully. The Government again gave a helping hand by first threatening to prevent the demonstrations by force and then backing down. Engels saw in these developments the beginnings of a movement in Britain, but he was very careful to state clearly what he meant: "The Social Democratic Federation is beginning to be something of a power, since the masses have absolutely no other organisation to which they can rally. The facts should therefore be recorded impartially, in particular the most important fact of all, namely that a genuinely socialist labour movement has come into being over here. But one must be very careful to draw a distinction between the masses and their temporary leaders" (Engels to Herman Schluter, Collected Works Vol.47). In short, Engels saw the development of the movement taking place in spite of the manoeuvres of Hyndman.

Against the international unity of the working class

Despite the scorching 'revolutionary' rhetoric of Hyndman's speeches, the SDF internationally allied itself with the reformist wing of the workers movement, since the revolutionary wing was decidedly marxist. In particular, the SDF worked with the Possibilists in France, who defended 'municipal socialism' against the marxist programme of the French Workers Party. In March 1886 Justice carried an article that described the Possibilists as the main socialist organisation in France, ignoring the creation of a workers group in the Chamber of Deputies a few months previously.

Hyndman's hostility to the creation of a marxist working class movement and his effective defence of the interests of the bourgeoisie, reached a high point in his attempt to sabotage the founding of the Second International. In this he was aided by the French Possibilists who, having split the working class movement in France, hoped to do the same internationally.

In October 1887 the congress of the German Social Democratic Party passed a resolution calling for an international congress "But since around this time the Trade Unions had summoned the London Congress, the German party was prepared to drop its congress, on condition that it would be allowed to participate - simply to participate!", however "The conditions of participation formulated by the union committee amounted to the exclusion of all German delegates" (Engels/Bernstein The International Workers Congress of 1889). Paul Brousse, the leader of the Possibilists, with a number of others attended the conference and won its support for their proposal to hold an international congress in 1889, which would exclude the other French workers' parties.

Despite this the SPD and Engels initially maintained their efforts to bring together a single international congress. A conference at the Hague in February 1889 proposed conditions for a single congress but was boycotted by the Possibilists (while Engels criticised the failure to invite the SDF). The Possibilists then issued invitations to their congress while Hyndman publicly attacked the Hague Conference as "a sort of private caucus" which would repeat "the wretched intrigues that broke up the old international" (Justice quoted in Tsuzuki, The Life of Eleanor Marx). These slanders made the stakes of the situation and the course of action clear to Engels, as he wrote in a letter to Sorge in June: "it is again the old split in the international that comes to light here, the old Battle of the Hague. The adversaries are the same, but the banner of the Anarchists has been replaced by the banner of the Possibilists... And the tactics are exactly the same. The manifesto of the Social Democratic Federation, obviously written by Brousse, is a new edition of the Sonvillier circular[1]" (Selected Correspondence).

Engels now pushed resolutely for a separate congress, working to win over the leaders of the SPD and transmit the lessons won with such difficulty in the struggle against Bakunin in the First International. In July the Marxist and Possibilist congresses were held in Paris. The former brought together 400 delegates from 20 countries while the latter regrouped a disparate gathering of Trade Unionists (a number of whom were drawn to the Marxist congress), Possibilists, Hyndman's clique and anarchists united solely by their opposition to marxism. The Marxist congress succeeded in resisting the attempts to disrupt it by the anarchists and ensured that the Second International was founded on the organisational advances made by the First.

Attempting to split the movement in Britain

Defeated at the international level, Hyndman nonetheless maintained his offensive against the unity of the working class movement by endeavouring to divide it in Britain. However, whereas in the past he had frequently been able to dominate the isolated and weak stirrings of the workers, he was now going against the rising tide of a movement that was gathering strength at home and drawing inspiration internationally.

Amongst a number of resolutions passed by the founding congress of the Second International, was one calling for international workers' demonstrations on May Day. This was enthusiastically supported by the Gas Workers and General Labourers Union which through a successful struggle to win the eight hour day for gas workers had gathered some 100,000 members. Eleanor Marx and Edward Aveling had actively worked with the union and their achievement was such that Hyndman felt it necessary to publicly slander them with accusations of taking money from the union. The Union now called for a mass demonstration in Hyde Park, to be held not on May 1st but on Sunday 4th, since this would enable more workers to attend. This was opposed by the London Trade's Council, which represented the old conservative unionists who excluded the unskilled workers. The Council made common cause with the SDF and they sought to pre-empt the Gas Workers proposal by booking Hyde Park for the 4th with the aim of preventing a demonstration dominated by the radical working class and the marxists. However, Aveling pushed the authorities to allow the original demonstration so that on 4th May two rival demonstrations were held. The result was another defeat for Hyndman and his allies. Engels, who watched the demonstrations, wrote a vivid account which clearly draws out the significance of the event: "On the one side we find conservative workers, whose horizons do not extend beyond the wage labour-system, and next to them a feeble but power hungry socialist sect; on the other side,the great bulk of workers who had recently joined the movement and who want no more to do with the Manchesterism[2] of the old Trade Unions, preferring to win their complete emancipation themselves, with allies of their own choice, and not with those imposed by a tiny socialist clique (...) The grandchildren of the old Chartists are stepping into the front line. For eight years the broad masses have been moving into action, now here, now there. Socialist groups have emerged, but none has been able to transcend the bounds of a sect; agitators and would-be party leaders, mere speculators and careerists among them, they have remained officers without an army... The tremendous movement of the masses will put an end to all these little sects and little groupings by absorbing the men and showing the officers their proper places" (Collected Works Vol .27). As if to confirm this last point, Engels noted that three entire branches of the SDF took part in the marxist demonstration, rather than that organised by their leaders.

Some conclusions on Hyndman and the SDF

Engels' analysis of the socialist sects can be seen to be confirmed in the case of the SDF. From its formation and until the last years of the 1880s, the SDF maintained its position as the largest socialist organisation in Britain and so was able to place itself at the head of the working class movement when it began to grow. This was the time when Hyndman's manoeuvres were generally successful, both in maintaining his own dominance and in ensuring that the movement remained small enough for him to manipulate. This was why he allowed the Tory Gold scandal to discredit socialism in the eyes of the working masses and why he preferred to direct marches of the unemployed rather than participate in unionism and strikes.

The rise of a mass workers movement inevitably began to weaken Hyndman's position and the establishment of the Second International on a marxist foundation was a serious setback, not only for Hyndman but for all like him who thrived on the weakness and division of the proletariat. The May Day demonstration not only expressed the growth of the workers' movement in Britain, but was also testimony to the international nature of the proletariat, since the victory of 1889 at the international level paved the way for the victory of 1890 at the national level.

These defeats did not mean the end for Hyndman, on the contrary he continued to work against the unity of the workers movement, particularly by seeking to introduce the poison of nationalism into the socialist movement by waging a campaign against `Hohenzollen militarism' and for an increase in the British Navy, which we will return to later. Above all, the lasting legacy of Hyndman's domination of the SDF was to inculcate a purist, 'revolutionary', attitude amongst successive generations of working class militants, including many of those who opposed Hyndman. The British revolutionary movement was dogged by confusion and even opposition to trade unionism and the winning of immediate reforms, which contributed to a situation where the minimum and maximum programmes of the working class were embodied in separate and opposing organisations, to the severe detriment of both, and resulting in the long-term weakening of the workers movement in Britain.

How then are we to understand Hyndman and the SDF? In the first part we identified Hyndman as an adventurer who put his personal advancement above the movement he claimed to support. In fact, his actions went beyond his own self-interest since they also objectively coincided with the aims of the bourgeoisie which, time and again, has sought to destroy the revolutionary movement from within. Moreover, his contacts with the bourgeoisie, from his meeting with Disraeli in 1880 to the deal with the Tories in 1885 poses questions about his relationship to the state. While we are not in a position to give a definitive answer today, we can note that on more than one occasion his contemporaries accused him of being an agent of the bourgeoisie. Engels, for his part, showed that Hyndman stood in continuity with Bakunin, that beyond their differences they were united in hatred of marxism and opposition to the development of a revolutionary movement based on the principles of centralisation and internationalism. Both were parasites on the workers' movement, opposing their dictatorial authority, based on affinity, sectarianism and intrigue, to the collective, formalised functioning of the proletariat. Just as Engels drew on the experience of the First International[3] to arm the Second, so today revolutionaries have again to learn from the past in waging the continuing battle against political parasitism and all who would destroy the revolutionary organisation.

If we have identified Hyndman as being opposed to the advancement of the proletariat and hostile to marxism, what of the Federation as a whole? Can it be considered to be a proletarian organisation? The answer to this is yes, and it is Engels who gives us the reasons for such an answer: specifically in his insistence on distinguishing between the leadership and the body of the organisation and, more generally, in his analysis of how the dynamic of the working class can take hold of organisations and transform them. This was why he advised Bernstein at the end of 1887 to deal with the SDF differently than before, and why, in a letter to Sorge, he criticised those who only look at the surface and see "only confusion and personal squabbles" when "under the surface the movement is going on [and] is embracing ever wider sections" (Selected Correspondence).

While the origins of the SDF were in a plethora of largely non-proletarian groupings and while it never went beyond being a sect it would be a serious mistake to see just this. Despite its origins the SDF was a socialist organisation and, in many of its parts, firmly marxist, even if the leadership was equally firmly hostile to marxism. The proletarian life within the SDF was expressed in the collaboration of members, especially outside London, with other socialists and in their participation in the life and struggles of the class. The contradiction within the organisation resulted in recurring opposition to Hyndman and the regular formation and departure of left-wing minorities. It is to this opposition, and particularly one of its most significant expressions, the Socialist League, that we will turn in the next part of this series.

North

First published in World Revolution 205 (June 1997)

[1] The Sonvillier circular was an attack by Bakunin's Alliance on the First International. See International Review 85 “The 1st International Against Bakunin's Alliance [4]”.

[2] The 'Manchesterism of the old trade unions' is a reference to their adherence to the 'Free Trade' policies of a group of bourgeois economists

[3] For more on the struggle in the First International see the articles in International Review nos. 84, 85, 87 & 88.

Rubric:

Part 3: The Socialist League and the fight against sectarianism

- 62 reads

Throughout the history of the Social Democratic Federation (see the second part of this series in World Revolution 205) opposition regularly developed to the policies and practices of the dominant Hyndman clique. At times this just resulted in the resignation of individual members - throughout its history many thousands passed through the SDF and it is clear that many of these were simply lost to the workers' cause. At other times organised left-wing factions emerged and were either expelled or left to found new organisations. In the 1880s the Socialist League and the lesser-known Socialist Union were formed, while in the first years of the 20th century the Socialist Party of Great Britain and the Socialist Labour Party were created. These splits are often presented as the consequence of personality clashes with the dictatorial manner of Hyndman but, in reality, they were a response to the needs of the workers' movement at the time. Thus, if we have characterised these organisations as the left-wing of the movement, this does not imply that they were simply more 'radical' than the SDF. In the 1880s the prerequisite was to go beyond the narrow sectarianism of the SDF and build a mass workers movement. The Socialist Union, which left after the 'Tory Gold' scandal, placed its emphasis on constitutional means, particularly Parliament, to achieve this. In the 1900s the primary task had become the combat against the growth of opportunism within the Second International, with both the SPGB and SLP defending the necessity for the revolutionary overthrow of capitalism against the illusions of reformism. If all of these organisations had serious weaknesses and confusions, it is nonetheless essential to grasp the dynamic underpinning them. Such a grasp makes it clear that the workers' movement in Britain was not something peculiar to this country, the product of its 'unique' history as we are so often told, but is irrefutably part of the international workers movement. In Germany, France and Russia it is possible to trace the same fundamental struggle to first go beyond the phase of sects and circles and then to defend the marxist and revolutionary nature of the workers' movement against opportunism and reformism. An examination of the history of the Socialist League, which is the focus of this third part of our series, of the struggles that took place within it and its ultimate collapse, confirms this analysis with precise detail.

The potential of the Socialist League

In August 1885, a few months after the foundation of the Socialist League, Engels wrote to Kautsky, "After the elections ... the basis for a socialist movement here will become broader and firmer. And therefore I am glad to see that the Hyndmanite movement will not take serious roots anywhere and that the simple, clumsy, wonderfully blundering, but sincere movement of the Socialist League is slowly and apparently surely gaining ground" (Collected Works Vol.47, p.320-1). At the start of the following year, in a letter to Sorge, after criticising the electoral manoeuvrings of the SDF, he concluded "but should it prove possible to educate within the Socialist League a nucleus with an understanding of theoretical matters, considerable progress will have been made towards the eruption, which cannot be long in coming, of a genuine mass movement" (ibid, p.394). This understanding of the potential arising from the evolution of the objective conditions is the fundamental reason why Engels gave his support to the creation of the Socialist League, giving advice to Morris, Bax and the Avelings, helping to write its draft constitution and contributing an article to Commonweal, the League's paper. In this last, he underlined that it was the deteriorating economic position of Britain that would lay the foundation for the revival of socialism, the implicit message in this being that socialists must work with this process, advancing with the workers and seeking to push them forwards, rather than seeking to impose a pure doctrine from outside.

The policy and organisation of the League

This strategy was clearly set out in the draft constitution, drawn up by Eleanor Marx and Edward Aveling with Engels' guidance, which called for participation in elections and support for trade unions and for other socialist bodies. The overriding aim was "to form a National and International Socialist Labour Party" (quoted in Thompson, William Morris: Romantic to Revolutionary p.381). This was adopted by the provisional council, formed immediately after the split, but then overthrown, with Morris' support, at the first conference of the League in July 1885 in favour of an anti-electoral position.

In a number of areas the League took important steps forward. At the programmatic level, the Manifesto of the Socialist League emphasised the revolutionary overthrow of society by a class conscious proletariat, rejecting "certain incomplete schemes of social reform", and firmly declaring its internationalism: “for us there are no nations, but only varied masses of workers and friends, whose mutual sympathies are checked or perverted by groups of masters and fleecers whose interest it is to stir up rivalries and hatreds between the dwellers in different lands". At the organisational level, and in direct contrast to the SDF, the League's paper was seen as expressing the views and being under the control of the organisation: "the Editor and Sub-Editor [Morris and Edward Aveling respectively] ... are acting as delegates of the Socialist League, and under its direct control: any slip in principles, therefore, and misstatement of the aims or tactics of the League, are liable to correction from that body" (introduction to Commonweal issue 1, vol.1). At a more general level, the League generally adopted a marxist approach to history. This was seen most clearly in the series “Socialism from the Root up”, written jointly by Morris and Bax, and published in the Commonweal between May 1886 and May 1888. The greater part of the series was devoted to an exposition of 'scientific socialism', including a precis of the economic analysis of Capital.

However, the weaknesses which played a large part in the eventual disintegration of the League were also present. Programmatically it failed to grasp the link between the struggle for immediate reforms and the goal of revolution, rejecting all palliatives, and particularly participation in elections, in favour of "the realisation of complete Revolutionary Socialism". Organisationally, despite the existence of an Executive Council and the holding of annual conferences, the structure was very informal, with the branches retaining a high degree of autonomy.

The result was that the League stood apart from the workers own struggles. If it preached the importance of a general strike, it failed to grasp the potential within the actual strikes going on under its nose, being content with an all-purpose leaflet which told workers that a strike just over wages "will be useless as a means of permanently bettering your condition and a waste of time and energy, and will entail a large amount of suffering on yourselves, your wives and families in the meantime" (quoted Thompson, op.cit. p.435-6). A similar approach was adopted towards the electoral struggle, with another all-purpose leaflet simply calling on workers not to participate. Consequently, the League placed the greatest emphasis on education, Morris arguing that "Education towards Revolution seems to me to express in three words what our policy should be..." (“Our Policy”, Commonweal Vol.2, No.14). The members of the League devoted their efforts to spreading the word, by mouth and in print, participating in the free-speech struggles that marked the mid 1880s, often showing extraordinary levels of courage, commitment and self-sacrifice for the cause, but nonetheless failing to respond to the workers’ movement growing around them, even when the workers showed their willingness to move towards socialism, as during the miners strikes in Scotland in 1887 when workers attended meetings in their tens of thousands.

Marxism versus anarchism

The isolation of the League from the real life of the working class, despite the sincerity and efforts of very many of its members, stemmed from its failure to grasp the tasks of the period and to build an organisation capable of carrying them out. This failure was not inevitable but was, fundamentally, the result of the struggle between the marxist and anarchist factions within the League.

These factions were present from the start. The anarchists were headed by Joseph Lane and Frank Kitz, who emerged from the ultra-radical milieu in London in the late 1870s and founded the Labour Emancipation League in 1881. Its programme united various traditional radical and Chartist demands with calls for the collectivisation of the means of production, while its activity, which focused on its base in the East End of London, included a call for a rent strike. In the same year, at the invitation of Hyndman, it participated in the conference that founded the Democratic Federation, the forerunner of the SDF, seeking to "set them up with the most advanced programme we could force on them" (Lane, quoted in Quail, The Slow Burning Fuse: The Lost History of the British Anarchists, p.25). The LEL affiliated to the SDF, but did not join in order to maintain its 'autonomy'. It took little part in the activities of the SDF until the split in 1884 when it sided with the seceders, although it had been asked to participate in the decisive-meeting by Hyndman who, presumably, thought he could rely on it a second time. Subsequently the LEL affiliated to the League. This time its members were to play a much more significant role, Lane and Kitz initially taking places on the provisional council and then on the Executive Council, where they formed the nucleus around which the anarchist faction developed within the League.

The marxist faction, which included Bax, Aveling, Morris and Eleanor Marx, suffered its first setback with the rejection of the draft constitution, although a proposal by Lane to transform the League into a federation of independent branches was defeated. Many of the faction, and Morris above all others, completely underestimated the danger posed by the anarchists and opened the door to their destructive influence. Only Eleanor Marx grasped the danger, writing to her sister Laura shortly after the establishment of the League "the Anarchists here will be our chief difficulty. We have many on our Council, and by and by it will be the devil to pay. Neither Morris, nor Bax nor any of our people know really what these Anarchists are: till they do find out is a hard struggle to make head against them - the more that many of our English men taken in by the foreign anarchists (half of whom I suspect to be police agents) are unquestionably the best men we have" (quoted in Tsuzuki The Life of Eleanor Marx, p.129). Her predictions were rapidly borne out. In April 1886 Engels wrote to Laura Lafargue "Here all is muddle. Bax and Morris are getting deeper and deeper into the hands of a few anarchist phraseurs, and write nonsense with increasing intensity" (Collected Works, Vol.47, p.438). In May Aveling resigned as Sub-editor of Commonweal (Bax replacing him) and shortly afterwards Eleanor Marx stopped writing her column of “International Notes”. By August Engels noted that "the League is going through a crisis" (Engels to Bebel, Collected Works Vol 47, p.471).

The struggle came to a head at the third conference in 1887 when the Marxists sought to overturn the anti-electoral and sectarian policy of the League. The main resolution, proposed by J.L Mahon, essentially reiterated the strategy of the draft constitution. It is possible that Engels helped to draft this resolution since, despite his reservations about the capacity of the League, he saw that the development of a broad workers' movement in Britain was imminent. During the preparation of the Conference the anarchists busily mobilised their forces whereas the Marxists were silent and inactive. At the Conference Morris played a decisive role, first seeking to put off a decision and then swinging behind the anarchists to defeat the Marxist resolution and restate the policy of abstention. Subsequently the Marxists attempted to work as a fraction within the League, establishing themselves in the Bloomsbury Branch and, paradoxically, within the Hoxton branch of the Labour Emancipation League, in which they were now in the majority. This work seems to have been done badly (the anarchists portraying it as a plot to stage a coup within the League) and at the fourth conference the attempt to change the League's policy resulted not only in defeat, but in the expulsion of the Bloomsbury Branch and the disaffiliation of the Hoxton LEL. Henceforth the League was in the hands of the anarchists.

Morris, although firmly declaring himself a marxist and opposed to anarchism, continued to underestimate the threat posed by the anarchists. At the founding conference of the Second International he joined with the others in the League delegation in protesting at the handling of the anarchists' attempt to disrupt the meeting. He also revealed his poor understanding of the organisation question in his report on the congress, when he concluded "such gatherings are not favourable for the dispatch of business and their real use is as demonstrations, and...it is better to organise them as such" (“Impressions of the Paris Congress II”, Commonweal, Vol.5, No.186). It was not until 1890 that he finally broke with the League and only in the few remaining years of his life that he began to grasp the dynamic of the real movement.

The anarchists gradually reduced the League to nothing, seeking to outdo each other in radical posturing, using Commonweal to advocate terrorism and assassination while breaking up the branches. If at this stage the presence of police spies and agents provocateurs became obvious (even to the anarchists), the decisive period was that of the confrontation between the marxists and anarchists. The potential of the League when it began ensured that the state paid close attention to it. We have seen already that Eleanor Marx suspected the presence of police agents amongst the foreign anarchists but, given the experience of the British state, it is impossible to rule out the likelihood that amongst the native anarchists was a smattering of state agents.

Towards the mass workers' movement

The degeneration of the Socialist League, as with the manoeuvrings of the SDF before it, prompted significant minorities to attempt to go beyond its limitations. This took various forms. Branches of the League, especially those in the provinces, developed links with other local socialist bodies, including the SDF, as well as with the trade unions. For example, in 1888 branches in Scotland supported the formation of the Scottish Labour Party. J.L Mahon, at one time Secretary of the League and stalwart of the anti-parliamentarians, changed his position and left the League to establish the Northern Socialist Federation and to work with the Scottish Land and Labour League, both organisations supporting participation in elections and unions. However, as we will see later in this series, many militants, in their eagerness to break from sectarianism, veered the other way and tended to see parliament as the only road to socialism, thereby succumbing to the arguments of reformism and opportunism. Again, this tendency arose from the objective situation, where the continuing expansion of capitalism enabled the workers movement to extract concessions from the bourgeoisie.

The promise of the Socialist League was not fulfilled. It failed to discharge the tasks demanded of it. However, along the way, through the struggle to spread the message to the class and through the confrontation with the anarchists a significant number of militants began to understand why and how to be part of the mass movement. The great weakness was that along the way much time and energy had been wasted. While the socialists were locked in their sects, the working class movement in Britain began to develop and leave them behind. This situation meant that the non-socialist and anti-socialist elements, with a helping hand from the state, had a disproportionate weight within the new movement. In the next part of our series we will look more closely at the beginnings of this movement, as a prelude to consideration of the place and role of the Independent Labour Party.

North

First published in World Revolution 208 (October 1997)

Rubric:

Part 4: 1880s and 1890s: revival of workers' struggle and the socialist response

- 97 reads

This series of articles began by outlining the resurgence of the working class movement in Britain at the end of the 1880s. It went on to deal with the particular roles of the Social Democratic Federation and the Socialist League, concluding that both failed to respond to the needs of the proletariat (see WR 198, 205 & 208). In this fourth part, we return to a more detailed consideration of the revival of struggle in the 1880s and 1890s, to show why and how it developed and to draw out both what it shared with the international workers' movement and what distinguished it.

The balance of class forces

While no mass political movement was created in Britain in the decades following the defeat of Chartism, the working class, nonetheless, constituted a force within society. The fundamental reasons for this were the strength of trade unionism within the working class and the bourgeoisie's own understanding of the potential threat posed by the proletariat. These points were emphasised by Engels in 1881 in an article on the Trades Unions in The Labour Standard. "The Act of 1824 [which repealed the Combination Laws which had banned Trades Unions] rendered these organisations legal. From that day Labour became a power in England. The formerly helpless mass, divided against itself, was no longer so. To the strength given by union and common action was added the force of a well-filled exchequer - `resistance money', as our French brethren expressively call it" (Collected Works Vol.24, p.384). The unions became "a power which has to be taken into account by any Government of the ruling class" (ibid, p.386), winning not only economic concessions, such as the regulation of wages, hours and factory conditions, but also political reforms with the gradual extension of the vote. However, they failed to use these "new weapons". The majority of union leaders remained staunch liberals. Indeed, as Engels showed, it was the bourgeoisie, "which knows their strength better than they do" (ibid) who took the initiative, 'volunteering' the extension of the vote to parts of the working class. The bourgeoisie was quite clear about its aims in doing this: "every man who is not presumably incapacitated by some consideration of personal unfitness or of political danger is morally entitled to come within the pale of the constitution" (Gladstone, quoted in Torr, Tom Mann and His Times). Thus, while the struggle for the franchise was an important aspect of the wider class struggle at this time, its acquisition was only a victory for the working class to the extent that it was consciously used as part of that wider struggle. Engels concluded the article in The Labour Standard by arguing that the unions' failure to use the franchise in this way meant that the working class had been "moving in the wrong groove" (op.cit).

The trade union struggle ensured that part of the working class shared in the advantages that flowed from Britain's economic supremacy but, as Engels repeatedly argued, the union struggle, by its nature, could not challenge the wages system itself. Furthermore, the very success of the unions fuelled illusions about the existence of common interests between the classes and helped create strong support for the Liberal Party within significant parts of the working class, thus ensuring that the political initiative lay more with the bourgeoisie than the proletariat. For this to change decisively there would have to be an equally decisive change in the objective conditions.

The start of the decline of British Capitalism

The early industrialisation of Britain gave it an advantage over all of its rivals that lasted for much of the 19th century. However, by the 1880s competitors such as France, Germany and America were threatening this monopoly. While their total productive capacity still lagged behind Britain at the start of the decade, its more rapid rate of increase indicated that this would not long remain the case. This sharpening of competition fuelled the growth of imperialism as each nation struggled to increase its share of the world market. The previously unexploited parts of the world, notably Africa and Asia, became the focus of intense rivalry in the last decades of the century.

In Britain, as Engels noted, the classical industrial cycle had begun to change with the periods of collapse lengthening and recovery becoming more difficult: "... what distinguishes the present period of depression, especially in cotton and iron is this, that it has now for some years outlasted its usual duration. There have been several attempts at a revival, several spurts; but in vain. If the epoch of actual collapse has been overcome, trade remains in a languid state, and the markets continue incapable to absorb the whole production" (“Iron and Cotton” published in Labour Standard 1881; Collected Works vol.24, p.411-2). There were depressions at the end of the 1870s and during the middle years of the 1880s (the Great Depression) while throughout there was a gradual decline in the rate of growth. These developments not only heralded the end of Britain's economic monopoly but were also the first signs of the end of the period of ascendancy of capitalism as a whole and the beginnings of its period of historical decline or decadence (see our pamphlet The Decadence of Capitalism [5]).

At the same time as these developments led to an increase of rivalry within the capitalist class, they also provoked an intensification of the struggle between the classes. The employers sought to protect their profits by increasing the exploitation of the working class, both by changes in working practices and attempts to keep down, or even cut, wages. By the turn of the century wages had ceased to increase and even moved into reverse. The recessions threw hundreds of thousands of workers into unemployment and destitution, with rates reaching 12% in 1879 and 10% in 1885-6, before falling back to 3 % during the relative recovery of the later 1890s.

The proletariat was hit very hard by these developments and initially membership of the unions slumped, but from the latter half of the 1880s on its combativity gradually recovered, with significant strikes taking place in the mines in Northumberland and in the engineering industry in Bolton. These strikes were marked by an increasing bitterness, the employers forming national organisations to protect their interests and the state intervening in a number of strikes, such as Manningham Mills in 1890 when police broke up the strikers’ meetings. This increasingly direct confrontation between the classes eroded the illusions weighing on the working class and created the conditions for a politicisation of the proletariat's struggle.

The economic struggle

The most significant aspect of the economic struggles of this period was the mobilisation of the unskilled workers. In March 1889, agitation by the gasworkers in London, with regular demonstrations of several thousand and the enrolment of 20,000 workers in the National Union of Gasworkers and General Labourers, forced the employers to concede an 8 hour day and a pay rise. Later the same year the London dockers' strike generated massive solidarity, with the marches and demonstrations involving 100,000 workers. Official figures for the period show 119,000 workers involved in disputes in 1888, 360,000 in 1889 and 393,000 in 1890, rising to a peak of 634,000 in 1893, and remaining high for the rest of the century.

This historic movement of the working class is often subordinated to the story of 'new unionism' and its leaders which, while of great importance, can obscure the real significance of the movement. In the dock strike for example, previous attempts at unionisation by Ben Tillet had only limited success and the strike itself began amongst non-union workers who, while they subsequently turned to Tillet for assistance, formulated their demands independently, as had the gasworkers previously (see Mann Tom Mann 's Memoirs, pp 58 & 61). Furthermore, while a large number of new unions sprang up subsequently around the country, both they and the gains they won frequently proved unsustainable. The dockers had to accept a compromise (although achieving their main demand of 6d an hour and 8d overtime) and the Gasworkers were defeated in a strike at the end of 1889. Between 1892 and 1894, the new unions only comprised some 107,000 out of the total of 1,555,000 union members.

The real success of the struggles lay in the mobilisation of the working class, in the demands advanced and in the determination with which they were fought. The dockers stayed out for five weeks, sustained by the solidarity of the proletariat internationally. An act in keeping with the foundation of the Second International that same year.

That socialists, such as Eleanor Marx, Will Thorne and Tom Mann were able to play a leading role was primarily a consequence of the maturation of the class consciousness of the proletariat in Britain. It also reflected the capacity of these socialists to break with the sectarianism of the main socialist organisations (even though Thorne and Mann remained members of the SDF) and grasp where the real movement of the working class lay. This movement was not towards the immediate acceptance of socialism, to which many workers remained hostile, but away from domination by bourgeois ideology and politics and towards independent class organisation.

The political struggle

This dimension of the class struggle generally developed in a far more dispersed and hesitant manner than the economic struggles.

Although the SDF and the Socialist League were never more than sects, they did have a lasting impact in some parts of the country. The SDF particularly had a presence in parts of Scotland and above all in Lancashire, where the involvement of some of its members in a number of industrial disputes had left a legacy of branches in towns such as Salford, Blackburn and Rochdale. Some of these were far less sectarian than the parent organisation and worked readily with other socialist and labour organisations. The splits from the SDF (see part 3 [6] of this series) had produced organisations which, while generally short-lived, had left some traces. These organisations had tended to react strongly against the 'revolutionary' purism of the SDF, the Socialist Union, for example, adopted exclusively reformist and legalistic positions.

In 1888 the Scottish Labour Party had been formed in the wake of Keir Hardie's failure to be elected as an independent labour candidate in Mid Lanark. Although it sought to draw in socialists, much of its platform was composed of traditional radical liberal demands and, more significantly, it showed a continued willingness to negotiate with the Liberal party to obtain electoral deals. Despite this, the election and its aftermath indicated that the grip of the Liberal party was weakening, although it sought to respond by adopting a more radical programme at the 1891 election. In other parts of the country similar efforts to field independent labour candidates in local and national elections gradually gained support, Hardie being elected in the West Ham South constituency in 1891.

In various parts of Britain independent labour organisations emerged. Labour Unions were established in Bradford, Halifax, Hartlepool and Keighley, the founding resolution of the first declaring that "its objects should be to advance the interests of workingmen in whatever way it might from time to time be thought advisable...its operation should be carried on irrespective of the convenience of any political party" (quoted in Howell, British Workers and the Independent Labour Party, p.179). In Manchester a local Independent Labour Party was established in 1892, the fourth clause of its constitution stated "That all members of this party pledge themselves to abstain from voting for any candidate for election to any representative body who is in any way a nominee of the Liberal, Liberal-Unionist or Conservative parties" (quoted in Pelling, Origins of the Labour Party, p.97). Other organisations included the Aberdare Socialist Society in South Wales and the Newcastle Labour Party.

Another important aspect was the growth of labour and socialist papers, such as the Labour Leader, Labour Elector, the Workman 's Times and Clarion at the national level, alongside a host of local or sectional papers, such as The Miner and the Yorkshire Factory Times. Even though many titles were short-lived and the motives of both proprietors and journalists were often questionable, they still expressed the forward movement of the proletariat. In 1892, the Workman 's Times, which was edited by Joseph Burgess, a long-time supporter of independent labour activity, launched an appeal for readers to send in their names to support the formation of an independent labour party. Over 2,000 replied and a number of branches were established, although without any national organisation.

Conclusions

The developments that we have sketched out are frequently presented as both uniquely 'British' (reflecting the 'common-sense' pragmatism of the British working class) and as simply the raw material of the ILP, which itself was but a preparation for the Labour Party, the inevitable destination of the working class. In reality, as we have repeatedly stressed, the working class movement in Britain was an integral part of the international movement although, as with each part, it was influenced by its particular situation.

In the first place, the international working class affirmed itself as a class with its own interests opposed to those of the ruling class. If this found its highest expressions in the great Social Democratic parties in countries like Germany and, above all, in the creation of the Second International, it could also be seen in the vibrancy of the proletariat's social life, in its clubs with their emphasis on education and in the proliferation of newspapers, journals and pamphlets. Engels repeatedly expressed confidence that this dynamic would rapidly lead the workers to socialism. Commenting on the strikes of 1889 he argued "Moreover, the people regard their immediate demands only as provisional although they themselves do not know as yet what final aim they are working for. But this dim idea is strongly enough rooted to make them choose only openly declared Socialists as their leaders. Like everyone else they will have to learn by their experiences and the consequences of their own mistakes. But as, unlike the old trade unions, they greet every suggestion of an identity of interest between Capital and Labour with scorn and ridicule, this will not take very long... " (Engels to Sorge December 1889, quoted Pelling op. cit). It was this dynamic which was expressed so forcibly in the massive May Day demonstration in London the following year and which prompted Engels to declare, "There can be no doubt that on May 4, 1890 the English working class joined the great international army" (“May 4 in London”, Collected Works vol. 27, p.66).

At the same time however, an opposite dynamic emerged, based on the very success of the unions and independent workers organisations in wrestling concessions from the ruling class. The bourgeoisie was able to grant these because of the immense continuing growth of capitalism. In the case of Britain, although it suffered from the loss of its monopoly position, it still remained immensely powerful and in the later 1890s enjoyed a period of prosperity in which the falling price of foodstuffs temporarily offset the decline in the rate of increase in workers' wages. This favoured not just a preoccupation with winning immediate reforms but also the development of an opportunist tendency which transformed this error into a political principle. This led eventually to the rejection of the class struggle, the abandonment of the revolutionary goal of the proletariat and, ultimately, to the defence of capitalism against the working class.

What particularly marked the situation in Britain was the existence of a number of factors which gave added weight to this tendency:

* Firstly, the weakness of the socialist movement in Britain, undermined organisationally by the parasitism of the dominant Hyndman clique in the SDF and the destruction of the Socialist League by the anarchists with aid from the state. The consequence was that, while Socialists played an active and significant part in the emerging movement, they did so in a dispersed and unorganised way that wasted much of their efforts. For many workers socialism was identified with the 'revolutionary' bluster of Justice (paper of the SDF) and the glorification of violence in Commonweal (paper of the Socialist League).

* The nature of the union movement in Britain gave an added weight to reformism. As we have seen, the traditional unions remained the dominant force, while the new unions were unable to sustain their original memberships and gradually moved towards the more traditional forms of organisation according to trade and level of skill.

* The activity of organisations such as the Fabian Society, which essentially advocated an opportunist and class-collaborationist policy and opposed marxism, gave a further push to reformism. Although the Fabian Society was small it was well organised and funded and the stupidities of the revolutionary sects gave it room in which to work.

* Lastly, the state itself worked actively against the working class movement. If its use of spies and agent-provocateurs was the most obvious aspect (and even here it was more skilled than its continental counterparts) the more dangerous was its ability to use concessions against the class struggle, particularly by playing the democratic card through the extension of the vote. This was underestimated throughout the workers movement, where the oppression of Bismarck in Germany and the Tsars in Russia was contrasted with the 'liberties' enjoyed in Britain. The weight of democratic illusions has remained a consistent weakness in the revolutionary movement in Britain.

However, it is essential to underline that the movement that came to life at the end of the 1880s and which flourished in the 1890s, was a genuine expression of the proletariat as a revolutionary class and that it had the potential to develop into the mass socialist organisation that Engels envisaged. Contrary to our bourgeois historians it was not pre-ordained that it would end in the Labour Party. The period which now began, and which lasted until the First World War, was one of an intense struggle for the creation of a mass workers party and against opportunism. It is the first part of this struggle, the founding years of the Independent Labour Party, that we will take up in the next article in this series.

North

First published in World Revolution 213 (April 1998)

Rubric:

Part 5: The Independent Labour Party and the pressure of reformism

- 64 reads

During the 1890s, the mass workers' parties succeeded in gaining many reforms that improved the living conditions of the working class. While the struggle for such reforms was an important aspect of the class struggle in this period, the winning of reforms brought the danger of nurturing illusions in the possibility of capitalism peacefully evolving into socialism. However, the marxist foundation of most of these parties ensured that, within a minority at least, there was determined opposition to the growth of reformism and opportunism, exemplified by the efforts of Rosa Luxemburg in the German Social Democratic Party. The working class in Britain was confronted by the same situation but with the crucial difference that it sought to create a class party in the face of the reformist tide and without an organised marxist fraction.

Between the late 1880s and the early 1890s the working class in Britain took up the struggle against its exploiters in a decisive and frequently spectacular manner. The previous part 4 of this series [7] traced the development of this movement at both the economic and political level, noting that the latter was characterised above all by a tendency to break from the grip of the Liberal Party, which had traditionally been supported by the majority of working class voters, and to move towards independence. Engels hailed this development as the start of a dynamic that would lead the working class to socialism, brushing aside the pretensions and phrase-mongering of sects like the Social Democratic Federation and other assorted would-be leaders.