August 2019

- 100 reads

April 1939: End of the Spanish Civil War and prologue to the Second World War

- 273 reads

Eighty years ago, one of the most important events of the 20th century, the Spanish Civil War, came to an end. This major conflict was at the heart of the world situation in the 1930s. It had been at the centre of international political attention for several years. It would provide a decisive test for all political tendencies claiming to be proletarian and revolutionary. For example, it was in Spain that Stalinism would play a part, for the first time outside the USSR, as the executioner of the proletariat. Likewise, it would be around the Spanish question that a decantation would take place within the currents that had fought against the degeneration and betrayal of the communist parties in the 1920s, a decantation dividing them into those who would maintain an internationalist position during the Second World War and those who ended up participating in it, such as the Trotskyist movement. Even today, positions on the events of 1936-1939 in Spain are central in the propaganda of the currents that claim to support proletarian revolution. This is especially the case for the different tendencies of anarchism and Trotskyism which, despite their differences, both agree that there was a "revolution" in Spain in 1936. A revolution that, according to the anarchists, went much further than that of 1917 in Russia because of the constitution of the "collectives" promoted by the CNT, the anarcho-syndicalist trade union, an analysis rejected at the time by various currents of the Communist Left, by the Italian Left and also by the German-Dutch Left.

The first question for us to answer therefore is: was there a revolution in Spain in 1936?

What is a revolution?

Before answering, we need to agree on what exactly is meant by "revolution". It is a particularly overused term since it is claimed in France for example by both by the extreme left (Mélenchon with his "Citizen Revolution") and by the extreme right (the "National Revolution" of the Front Nationale). President Macron himself entitled the book setting down his political programme, "Revolution".

In fact, beyond all the fanciful interpretations, the term "Revolution" has historically expressed and entailed a violent change of political regime where the balance of power between social classes is overturned in favour of those representing progressive change in society. This was the case with the English Revolution of the 1640s and the French Revolution of 1789, both of which attacked the political power of the aristocracy in the interests of the bourgeoisie.

Throughout the 19th century, the political advances of the bourgeoisie at the expense of the nobility represented progress for society. And this is because at that time the capitalist system was experiencing growing prosperity and setting out to conquer the world. However, this situation would change radically in the 20th century. The bourgeois powers had finished sharing out the world between them. Any new conquests, whether colonial or commercial, would involve challenging the claims of a rival power. This gave rise to the increase in militarism and the outbreak of imperialist tensions that led to the First World War. This was a sign that capitalism had become a decadent and obsolete system. The bourgeois revolutions were no longer relevant. The only revolution on the agenda was the one to overthrow the capitalist system and establish a new society free of exploitation and war, i.e. communism. The only subject of this revolution is the class of wage earners that produces most of the world's social wealth, the proletariat.

There are fundamental differences between bourgeois revolutions and the proletarian revolution. A bourgeois revolution, i.e. the seizure of political power by the representatives of a country's bourgeois class, is the outcome to a whole historical period during which the bourgeoisie has acquired a decisive influence in the economic sphere through the development of trade and techniques of production. The political revolution, the abolition of the privileges of the nobility, constitutes an important (although not indispensable) step in the growing control by the bourgeoisie over society, which enables it to achieve and accelerate this process of control.

The proletarian revolution does not in any sense emerge at the end of a process of economic transformation of society, but on the contrary is active from the very start. The bourgeoisie had been able to establish its own economic “islands” within feudal society, with trade in the towns and other commercial networks, 'islands' that gradually would grow and be consolidated. It's nothing like this for the proletariat. There can be no islands of communism in a global economy dominated by capitalism and market forces. This was the dream of the utopian socialists such as Fourier, Saint-Simon and Owen. But, despite all their goodwill and their often profound analyses of the contradictions of capitalism, their dreams clashed with and were shattered by the reality of capitalist society. The fact is that the first stage of the communist revolution consists in the seizure of political power by the proletariat worldwide. It is only through its political power that the revolutionary class will be able to gradually transform the global economy by socialising it, by abolishing private ownership of the means of production along with market relations.

There are two other basic differences between bourgeois revolutions and the proletarian revolution:

- Firstly, while bourgeois revolutions have taken place at different times depending on the economic development of each particular country (there is more than a century between the English and French revolutions), the proletarian revolution must be concluded within the confines of the same historical period. Should it remain isolated within a single country or within a few countries, it would be condemned to defeat. This is what happened to the Russian revolution of 1917.

- Secondly, bourgeois revolutions, even extremely violent ones, still retained most of the state apparatus of feudal society (the army, police, legal system and bureaucracy). In fact, the bourgeois revolutions took charge of modernising and perfecting the existing state apparatus. This was possible and necessary since this type of revolution provided for a process of succession between the two exploiting classes, the nobility and the bourgeoisie, to the helm of society. The proletarian revolution is completely different. In no way can the proletariat, the exploited class at the heart of capitalist society, use the state apparatus designed and organised to guarantee this exploitation, and to suppress the struggles against this exploitation, for its own benefit. The first of the tasks of the proletariat in the course of the revolution will be to arm itself in order to destroy the state apparatus from top to bottom and to set up its own organs of power based on its mass unitary organisations with elected delegates revocable by general assemblies: the workers' councils.

1936: a revolution in Spain?

On July 18, 1936, following a military coup against the Popular Front government, the proletariat took up arms. It was successful in defeating the criminal enterprise led by Franco and his associates inside most major cities. But did it then take advantage of this situation, of its position of strength, to attack the bourgeois state? A bourgeois state which, since the establishment of the Republic in 1931, had already distinguished itself in the bloody repression of the working class, particularly in the Asturias in 1934 where 3,000 were killed. The answer is 'absolutely not!'

For sure the workers' response was initially a class action, preventing the coup from succeeding. But, unfortunately, the workers' energy was quickly channelled and ideologically recuperated behind the state banner by the mystifying force of the Popular Front's "antifascism". Far from attacking and destroying the bourgeois state, as was the case in October 1917 in Russia, the workers were diverted and recruited into defending the republican state. In this tragedy, the anarchist CNT, the most powerful trade union movement, played a leading role in disarming the workers, pushing them to abandon the terrain of the class struggle and capitulate, handing them over, with their hands and feet bound, into the arms of the bourgeois state. Instead of leading an attack on the state aimed at destroying it, as they have always claimed to want to do, the anarchists took charge of some of the ministries, stating, as Federica Montseny, anarchist minister of the republican government did:

"Today, the government, with the power to control the state organs, has ceased to be an instrument of oppression against the working class, just as the state no longer acts as an organism that divides society into classes. Both will oppress the people much less now that members of the CNT are involved in them”. The anarchists, who claim to be the state's "worst enemies", were thus able, using this type of rhetoric, to lead the Spanish workers into a pure and simple defence of the democratic state. The working class was diverted from its own political goals into supporting the "democratic" faction of the bourgeoisie against the "fascist" faction. This reflects the full extent of the political, moral, and historical bankruptcy of anarchism. Where it was politically dominant in the Iberian peninsula, anarchism showed its total inability to defend class politics, to stand up for working class emancipation. The class was simply led to defend the democratic bourgeoisie and the capitalist state. But the bankruptcy of anarchism did not stop there. By pretending it could lead the revolution on the basis of local actions that gave rise to the "collectives" of 1936, it actually rendered a proud service to the bourgeois state;

- on the one hand, it made possible the reorganisation of the Spanish economy in the interest of the war effort of the republican state, i.e. it supported representatives of the democratic bourgeoisie, against the "fascist" faction of the same bourgeoisie;

- on the other hand, it diverted the proletariat away from taking a generalised political action and into taking direct charge of the management of the factories and plants. This also benefitted the State and therefore the bourgeoisie. The workers were recruited into the "collectives" to deal with day-to-day production, into abandoning a global political activity and all concern for the real needs of the working class in favour of managing local enterprises, leaving them with no contacts between them.

While the proletariat was master of the streets in July 1936, in less than one year it was displaced by the coalition of republican political forces. On May 3, 1937, it made one last attempt to challenge this situation. On that day, the "Assault Guards", police units of the Government of the Generalitat of Catalonia - in fact they were tools of the Stalinists who had gained control over them - tried to occupy the Barcelona telephone exchange that was in the hands of the CNT. The most combative part of the proletariat responded to this provocation by taking control of the streets, erecting barricades and going on strike; an almost general strike. The proletariat was fully mobilised and certainly had weapons, but it didn't have a clear perspective. The democratic state had remained intact. It was still on the offensive, contrary to what the anarchists had said, and had in no way given up plans to suppress attempts at resistance by the proletariat. While Franco's troops voluntarily brought an end to the offensive at the Front, the Stalinists and the republican government crushed the very workers who, in July 1936, had defeated the fascist coup d'état. It was at this moment that Federica Montseny, the most prominent anarchist minister, called on the workers to stop fighting and to lay down their arms! So it was a real stab in the back for the working class, a real betrayal and a crushing defeat. This is what the magazine Bilan, publication of the Italian Communist Left, wrote on this occasion: "On July 19, 1936, the proletarians of Barcelona overpowered the attack of Franco's battalions THAT WERE ARMED TO THE TEETH USING THEIR BARE HANDS. On May 4, 1937, these same proletarians, NOW DISARMED, left behind them many more fallen victims on the streets than in July when they had had to repel Franco; and now it was the antifascist government (even including the anarchists, to which the POUM indirectly gave solidarity) that unleashed the scum of the repressive forces against the workers".

In the widescale repression that followed the defeat of the May 1937 uprising, the Stalinists were actively engaged in the work of physically removing any "troublesome individuals". This was what happened, for example, to the Italian anarchist activist, Camilo Berneri, who had had the lucidity and courage to make a damning criticism of the CNT's policy and the action of the anarchist ministers in an "Open Letter to Comrade Federica Montseny".

To claim that what happened in Spain in 1936 was a revolution that was "superior" to the one that took place in Russia in 1917, as the anarchists do, not only totally turns its back on reality, but constitutes a major attack on the consciousness of the proletariat by discarding and rejecting the most precious experiences of the Russian revolution: in particular those of the workers' councils (the Soviets), the destruction of the bourgeois state, the appeals to proletarian internationalism and the fact that this revolution was conceived as the first stage of world revolution and gave an impetus to the constitution of the Communist International. Despite the anarchists’ assertions to the contrary, proletarian internationalism was proven to be quite alien to the majority of the anarchist movement, as we will see later.

The Spanish Civil war, a preparation for the Second World War

The first thing that confirms our view that the Spanish Civil War was only a prelude to the Second World War and not a social revolution, is the very nature of the fighting between different fractions of the bourgeois state, republicans and fascists, and that between nations. The CNT's nationalism led it to call explicitly for the world war to save the "Spanish nation": "Free Spain will do its duty. In the face of this heroic attitude, what will the democracies do? It is to be hoped that the inevitable will not be long in coming. Germany's provocative and blunt attitude is already unbearable. (...) Everyone knows that, ultimately, the democracies will have to intervene with their air squadrons and armies to block the passage of these hordes of fanatics..." (Solidaridad Obrera, CNT newspaper, 6 January 1937, quoted by Proletarian Revolution No. 238, January 1937). The two battling bourgeois factions immediately sought outside support: not only was there a massive military intervention by fascist states that delivered air support and modern army weapons to the Francoists, but the USSR was also involved in the conflict, supplying arms and "military advisors". There was enormous political and media support, all over the world, for one bourgeois camp or the other. By contrast, no great capitalist nation had supported the Russian Revolution in 1917! Quite the opposite: they had all done what they could to isolate it and fought against it militarily, trying to drown it in blood.

One of the most spectacular illustrations of the role of the war in Spain in preparing the ground for the Second World War was the attitude of many anarchist militants towards it. Thus, many of them became involved in the Resistance, i.e. the organisation representing the Anglo-American imperialist camp on French soil that was occupied by Germany. Some even joined the regular French army, notably the Foreign Legion or General Leclerc's Second Armoured Division; this same Leclerc would later be actively involved in the colonial war in Indochina. Thus, the first tanks that entered Paris on 24 August 1944 were driven by Spanish soldiers and sported the portrait of Durruti, an anarchist leader and commander of the famous "Durruti column", who himself died outside Madrid in November 1936.

All those who, while claiming to be part of the proletarian revolution, took up the cause of the Republic, of the "democratic camp", generally did so in the name of the "lesser evil" and against the "fascist danger". The anarchists promoted this democratic ideology in the name of their "anti-authoritarian" principles. According to them, even if they admit that "democracy" is one of the expressions of capital, it still constitutes a "lesser evil" for them compared to fascism because, it is obviously less authoritarian. That's total blindness! Democracy is not a "lesser evil". On the contrary! It is precisely because it is capable of creating more illusions than the fascist or authoritarian regimes, that it constitutes a weapon of choice of the bourgeoisie against the proletariat.

Moreover, democracy is not to be underestimated when it comes to suppressing the working class. It was the "democrats", and even the "Social Democrats", Ebert and Noske, who had Karl Liebknecht and Rosa Luxemburg murdered, along with thousands of workers, during the German revolution in 1919, bringing to a halt the extension of the world revolution. Where the Second World War is concerned, the atrocities committed by the "fascist camp" are well known and documented, but the contribution of the "democratic camp" cannot be forgotten: it was not Hitler who dropped two atomic bombs on civilian populations, it was the "democrat" Truman, the president of the great "democracy" of the United States.

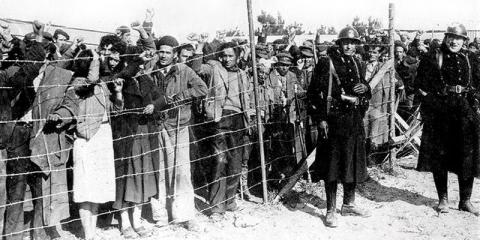

And in looking back at the Spanish Civil War, we should remember the welcome that the French Republic, the champion of "human rights" and "Liberté-Égalité-Fraternité", gave to the 400,000 refugees who fled Spain in the winter of 1939 at the end of the civil war. Most of them were housed in concentration camps like cattle surrounded by barbed wire, under the armed guard of the gendarmes of French democracy.

The proletariat must learn the lessons of the Spanish War:

- Unlike those who want to bury the proletariat and seek to discredit its struggle, those who think that the tradition of the Communist Left is "obsolete" or "old fashioned", that we should free ourselves from the revolutionary past of the proletariat, that Spain was a "superior" revolutionary experience and that finally we should forget the past and "try something different", we affirm that the workers' struggle remains the only way forward for the future of humanity. Therefore it is essential that we defend the working class's legacy and its traditions of struggle, in particular the need for class autonomy in fighting uncompromisingly for its own interests, on its own class terrain, with its own methods of struggle and its own principles.

- A proletarian revolution is not at all the same as the "antifascist" struggle or the events in Spain in the 1930s. Quite the contrary, it has to situate itself on the political terrain of the conscious workers' struggle, based on the political force of the workers' councils. The proletariat must maintain its self-organisation and its political independence from all factions of the bourgeoisie and from all ideologies that are alien to it. This is what the proletariat in Spain was unable to do since, quite the contrary, it bound itself, and therefore surrendered, to the left-wing forces of capital!

- The Spanish Civil War also shows that it is not possible to begin "building a new society" through local initiatives at the economic level, as anarchists choose to believe. Revolutionary class struggle is first and foremost an international political movement and not limited to preliminary economic reforms or measures (even through seemingly very radical "experiments"). The first task of the proletarian revolution, as the Russian Revolution has shown us, must be a political one: the destruction of the bourgeois state and the seizure of power by the working class on an international scale. Without this, it is inevitably doomed to isolation and defeat.

- Finally, democratic ideology is the most dangerous of all those promoted by the class enemy. It is the most pernicious, the one that makes the capitalist wolf look like a protective lamb and "sympathetic" to the workers. Antifascism was therefore the perfect weapon in Spain and elsewhere used by the Popular Fronts to send workers to be massacred in the imperialist war. The State and its "democracy", as a hypocritical and pernicious expression of capital, remains our enemy. The democratic myth is not only a mask of the state and the bourgeoisie to hide its dictatorship, its social domination and exploitation, but also and above all, the most powerful and difficult obstacle for the proletariat to overcome. The events of 1936/37 in Spain amply demonstrate this and it is one of their most important lessons.

ICC, June 2019

Rubric:

Brexit: a quagmire for all factions of the ruling class!

- 408 reads

The following article was written before many of the most recent twists in the continuing Brexit drama, such as the confirmation of the prorogation of parliament, the bill designed to prevent a No Deal Brexit, Boris Johnson’s attempt to have a general election, and the expulsion of 21 moderate Tory MPs from the party. Events have confirmed that the “situation is a clear expression of the fragmentation resulting from the present phase of capitalist decline”. The fact that the opponents of a No Deal Brexit have made advances in parliament shows that the Brexiteers do not have things all their own way. But defeats in parliament for Prime Minister Johnson do not mean the cause of Brexit is lost, especially if the threats to break the law by Johnson and Gove are followed up in practice.

It is possible to see other expressions of the rally of moderates elsewhere. In Italy, for example, when Matteo Salvini’s League withdrew from the government, instead of being a step towards a Salvini takeover, it led to a coalition between the Five Star Movement and the Democratic Party. This might only be a short-lived interlude, but it does show that the battle between the factions of the ruling class is not a one-way street toward populism and the extremes.

However, the underlying problem is still there for the bourgeoisie. The loss of control of the political apparatus, the escalation of the conflicts between different factions means the deepening of the political crisis, which will be further worsened by the development of the economic crisis.

The formation of a new government in London under Boris Johnson does not resolve the political crisis and the power struggle within the British ruling class which became a dominant factor in the political life of that country since the Brexit Referendum of June 2016. On the contrary: with the appointment by the Conservatives of Johnson as their new leader and Prime Minister, this crisis has reached a new stage, the power struggle a new degree of intensity. The new phase of this power struggle is not in the first instance one between Johnson and his so called moderate inner party opponents, or between Johnson and the Labour opposition, or between the PM and the staunchly Remainer first minister of Scotland, Nicola Sturgeon. As the London Sunday paper The Observer and the Swiss Neue Zürcher Zeitung both concluded, the opponent Johnson and the Tories are mainly trying to counteract is Mr. Brexit himself: Nigel Farage. The calculation (or the gamble) of Johnson is to ‘deliver Brexit’ by October 31, with or without a deal (as Johnson puts it, ‘do or die’) and if possible without calling a General Election beforehand. Otherwise he risks being obliged to form a coalition government with the new Brexit Party of Farage in order to deliver his Brexit. Farage, the reckless outsider of British politics, would thus gain a direct say on government policy (something the established so-called elites want to avoid). On the other hand, should he be prevented by the present parliament to deliver his Brexit on time as promised, this would be likely to give considerable additional momentum to the political career and ambitions of Farage. The problem for Johnson about this (at the time of writing) is that it is not sure that the present parliament would accept whatever deal (or no deal) Johnson presents to it. It would also be possible for the Prime Minister to sidetrack parliament (for example by temporarily suspending it). But some of his opponents in Westminster have already declared they would consider such a procedure to be a coup d‘État, a veritable Putsch. In a word: The mess is becoming a quagmire. This situation is a clear expression of the fragmentation resulting from the present phase of capitalist decline, of each for himself, at every level: economic, military, social, political. The actors in this process, while not being passive, are largely determined by it.

The political situation (which, for the moment, is much worse than the economic one) is going from bad to worse. The creeping paralysis of the past three years threatens to get out of hand. In this context, it should be noted that, if the new PM is putting all his bets on a quick Brexit at all costs, this is not because he thinks this course of action is necessarily in the best interest of British capitalism. In fact it is well known that Johnson was not particularly convinced of the benefits of Brexit at the time of the referendum, that he reacted with surprise and some dismay to the result. His main motive for supporting the Leave camp seems to have been his ambition to build up his own power base in the Conservative Party in order to challenge the party leader and PM of the time, David Cameron. Caught on the wrong foot by the victory of the Leave camp at the referendum, he soon realised that the putting into practise of this verdict would prove to be a thankless task. He thus momentarily withdrew (or rather: postponed) his bid for party leadership, preferring to leave the dirty work to someone like Theresa May. The main concern of Johnson, therefore, seems in reality not to have been Brexit, but his own political career. The fact that today, three years on, he has successfully bidden for party and state leadership, tells us something about the changes in the balance of forces within the ruling class which have taken place since 2016. At the time the Referendum was called, the two opposing camps were clearly drawn up, each behind their respective leader: Cameron and Farage. Farage was an upstart, operating outside the established party-political apparatus. Cameron, as opposed to this, was not only Prime Minister, he had the support of a majority of the Powers That Be both within his own Tory party and in Labour (the main opposition party) as well as that of the even more firm Remainers from the Liberal Democrats and the Scottish Nationalists. Initially, the outcome seemed almost a foregone conclusion. But the more the campaign of Farage’s UKIP gathered momentum, the more Tories (including Johnson) began to join in with the Brexiteers. For the most part, this was probably not because they had been convinced by UKIP’s arguments. Not that they did not share the latter’s resentment against Europe for having made the country turn its back on its former Empire. But their main motivation seems to have been a tactical one: that of taking the wind out of the sails of Farage in order to sidetrack him.

But the Tories miscalculated.

The Remainers lost.

And this, in turn, altered the balance of forces within British bourgeois politics. It will suffice to recall that ‘Brexit means Brexit’ Theresa May, who became the successor to Cameron, had originally been a Remainer, as had been many of those who today present themselves as hard-line Brexiteers within the Conservative Party. Indeed the remaining clear cut, Cameron-style Remainers in the Tory Party (‘grandees’ like Heseltine, or current MPs such as Dominic Grieve) are currently having a hard time. As of now, the Brexiteers have more or less taken over the Party, and above all they have taken over the government. One of the architects of the Brexit campaign, Dominic Cummings, has become chief advisor to the government.

The situation transformed by the referendum result

Before the Referendum, the choice was between leaving or remaining in the European Union. As long as this was the case, a majority within the ruling class clearly favoured the latter option. But after the Referendum this choice was no longer on the table. Theoretically, of course, it could still be attempted to hold a second referendum with the aim of winning a majority for Remain. But such a manoeuvre would be difficult. It is by no means certain that the outcome would be any different from the first time round. And such an attempt would even be dangerous. It would risk deepening the already existing divisions around the Brexit issue, including those within the ruling class itself. This is why this option is at present not much favoured among its representatives. So today, the momentum is heading towards a no-deal Brexit, although, as shown in the European parliament elections, there is a polarisation between no-deal and no Brexit. Theresa May spent most of her premiership trying to persuade the ‘political class’ that her Brexit with a deal should be accepted as the lesser evil. Without success. From the point of view of the ruling class, May’s deal is certainly a much less attractive option than remaining in the EU had been. The lesser evil? For many of the country’s ‘policy makers’ and ‘opinion makers’ it is not really an option at all. They see it as amounting to the UK still by and large having to follow EU policy on many issues, but no longer having a say in formulating them.

This dilemma has caused a growing disorientation within sizeable parts of the state apparatus. One of the products of this mess has been the development of a whole swathe of what we might call waverers. Their state of mind is brought to light by the rhetorical and voting behaviour of a number of members of parliament: MPs who either advocate one thing today and the opposite tomorrow, or who have no idea how to position themselves, and who apparently would prefer not to do so for as long as possible. Impossible to know in advance which side they might take in the end.

Another result has been the crystallisation, within the Conservative Party, of a growing axis of real hardline Brexiteers. ‘Real’ in the sense that they advocate a no-deal Brexit, not out of career opportunism or tactical considerations, but because they really agree with Nigel Farage. This hard core regroups around figures like Jacob Rees-Mogg, who argues that a no-deal Brexit is the best thing which could possibly happen. This group undoubtedly played a leading role in the downfall of May (after repeatedly sabotaging her different attempts to get her deal accepted) and her replacement by Johnson. Although possibly still a minority within the party, it has the advantage over the other Tories right now of knowing exactly what it wants. And indeed, its internal party opponents are at present pushed very much onto the defensive, their radius of action restricted by the fear that their time-honoured Conservative Party is in existential danger. Their fear is that the hard-liners, if they do not get their way, might rebel and, by one means or another, join up with Farage. Possible scenarios: a split in the party, or its ‘hi-jacking’ along the lines of what Trump has done with the Republican Party in the United States.

Populism and the manipulation of social discontent

One thing at least emerges clearly, which is that the established so-called elite has underestimated the factor of political populism in general, and the role of Farage in particular. We can readily agree that the term ‘populism’ is not very precise and in need of further elaboration. This notwithstanding, the term ‘populism’ itself already contains an important kernel of truth, as the present example of Britain clearly illustrates. One of the main reasons for the success of Farage has been that he knows how to mobilise popular discontent, stoke up diffuse resentments, and manipulate widespread prejudices, in order to counter the propaganda of the leading factions of his own capitalist class. Britain was far from being the only European country where the ruling class, whenever it could, blamed the effects of its attacks against its ‘own’ working population on ‘Brussels’. But in Britain, this ploy was used consistently over such a long time, with an intensity, and to a degree of hysteria, almost unparalleled anywhere else. Moreover, this policy reached a new crescendo at the beginning of the new century, when a number of Eastern European countries joined the European Union. Part of the deal accompanying their integration was that the already existing member states were allowed to restrict the influx of labour from the East during a transitional phase of up to eight years. The concern behind this was to ensure that the downward pressure on wages in Western Europe which the competition from the east on the labour market was going to exert could be phased in, in order to avoid a too-sudden exacerbation of social tensions. Only three countries renounced the use of this transitional mechanism: Sweden, Ireland and… the United Kingdom. In the case of the latter, the main motive was not hard to detect. Whole sectors of British industry were losing out to a German competition which was benefiting, among other things, from radically lowered wages thanks to the (in)famous ‘Agenda 2010’ austerity policy put in place there under the Social Democratic/Green government of Gerhard Schröder. In face of this, an enormous influx of cheap Eastern European labour was exactly what British capitalism needed in order to counteract this German offensive. And at the level of labour market policy, the measure was a complete success. Many workers in Britain lost their jobs, replaced by imported ‘EU citizens’ in a more or less desperate economic situation, and as such obliged to work more for less. Not only were the latter correspondingly ‘highly motivated’ (as the capitalist euphemism likes to put it), many of them were also highly qualified. This policy did not only help to lower real wages. It had a series of additional drastic consequences at the social level, best described under the term: capitalist anarchy. Almost no preparations had been made for such an influx of hundreds of thousands of new inhabitants. The already acute situation at the level of housing, health care and public services like transport and health, was brought to the brink of collapse. And this not only in the Greater London area, but also in regions which until then had been much less a destination of European Union labour migration. An example of the mood reigning at the time was the announcement by the National Health Service in the London area that it was contemplating ceasing to train nurses, since more than enough already trained ones from abroad were now pouring in.

But that is not all. More or less with a single voice, the UK government and the allegedly so democratic and pluralistic media presented this influx as something being imposed on the country by the EU, which London could do nothing about: a good example of ‘fake news’! So when Cameron made his capital blunder of calling his referendum about the continuation or not of Britain´s EU membership, Farage knew exactly what he was doing when he made ‘taking back control of our frontiers’ a lynchpin of his Brexit strategy. In so doing he was able to kill two birds with one stone: directing popular frustration against his own bourgeois rivals, and at the same time turning worker against worker and thus undermining working class solidarity. The only difference, at this level, to his populist counterparts in Europe such as Salvini in Italy or the AfD in Germany is that he mobilised against European Union migrants more than against refugees.

A transatlantic cooperation against the European union

But there is also a second means which enabled Farage to take his political opponents by surprise. This was the support he obtained from powerful bourgeois factions outside the UK. Much has been said about the role of Russia in the Brexit campaign. It is evident that Moscow had an interest in the UKIP side winning the Referendum, and probably did everything in its power in favour of it. However, it is nothing new that the British ruling class likes to blame everything and anything on Russia, and in fact has a vested interest in exaggerating its role. No, the foreign aid we are referring to here is that coming from the other side of the Atlantic. It’s not for nothing that the US media have started to refer to the Brexit Referendum as having been a kind of dress rehearsal for Trump’s victory at the 2016 American presidential elections. Both were, to an important degree, taken in hand by the same structures such as the (now defunct) electoral algorithms of the Cambridge Analytica firm owned by the American mathematician and hedge fund billionaire Robert Mercer, or the media empire of the Australian Trump supporter Rupert Murdoch.

There is a long tradition of close collaboration between leading factions of the British and American bourgeoisie, including on economic questions. Famous (or infamous) is the leading role in the establishment of the ‘neo-liberal’ world economic order played by the combined efforts of Margaret Thatcher (GB) and Ronald Reagan (US). More recently, in face precisely of the Brexit Referendum, Barack Obama tried to come to the rescue of David Cameron by throwing in his own political weight and rhetorical skills in his favour. But on this occasion (perhaps the first time ever on such a scale), the ‘official’ support of the Obama administration for the British government was counteracted by a second, ‘unofficial’ transatlantic collaboration: that of the future ‘Trumpists’ for the Brexiteers. The latter collaboration was motivated by a shared conviction that, in the present historic phase, ‘multilateralism’, whether in the form of the European Union or, for example, of the Chinese One Road One Belt Initiative are increasingly likely to be used as battering rams against the interests of the remaining world power, the United States, but also against those of the former world leader, the United Kingdom. Above all, they suspect structures such as the European Union of being prone to manipulation by potential challengers such as China and Germany. The two latter powers in particular are seen in London and Washington as profiting from the single EU market to spread their influence throughout continental Europe. According to this point of view, held by Trump and others, in a more fragmented world deprived of much of its previous ‘multi-lateral’ structure, the strongest power, the USA, would fare best, being in a better position to impose itself on the others. But according to the Brexiteers, the UK could also benefit from a more unilateral/bilateral (dis)order thanks to its historic experience, its longstanding world-wide connections and its status as a world financial power. In this context, the long-term goal of the hard-line Brexiteers cannot restrict itself to taking the UK out of the European Union. As has been pointed out again and again (already by Cameron during the Referendum campaign), in a world in which Britain coexists with, but is outside of the EU, London risks finding itself considerably at a disadvantage compared with the EU. This is why the hard-line Brexiteers cannot be satisfied with withdrawing the UK from the EU. Their final goal is to contribute to the demolition of the EU, at least in its present form. Brexit, in their eyes, is a first step in that direction.

It goes almost without saying that this policy is a gamble of the most hazardous kind. No wonder it was not at all what the traditional political establishment wanted. It is the objective world historical situation – the crumbling of the existing capitalist order – which lends this unlikely project a degree of plausibility.

The response of the European Union

It certainly did not go unnoticed in London how, in recent years, Germany has taken important steps towards affirming its leadership ambitions within the European Union. It has in particular used economic means to that end. It has largely succeeded in converting Eastern Europe into a kind of extended assembly line of Western European, but above all of German industry. And it has profited from its key role as guarantor for the Euro (the currency shared by a majority of EU member states) to at least partly impose its economic policies on Southern Europe. These measures helped, at least for a while, to counter the centrifugal tendencies within the European Union. However, the past few years have witnessed a series of developments threatening this cohesion. As we have discussed in this article, both Brexit and the policy of Trump in the United States at least partly represent an attack against the EU. But also within the European Union itself, in continental Europe, the already fragile cohesion has been more and more strained by developments such as the rise of populism (which in general tends to be more or less hostile towards ‘Brussels’) or the growing discontent of other member states with German economic policy (including the two heavyweights France and – in particular – Italy).

The interaction of these different tendencies and counter-tendencies is complicated and always good for surprises. Indeed, the 27 Remainer EU states have surprised themselves by how well they have succeeded so far in closing ranks in the Brexit negotiations, resisting, up until now, all the attempts of London to divide them against each other. Indeed, the very global turbulences of which Brexit is a part, and in particular the explosion of trade wars centred around, but not restricted, to the big two USA and China, have reminded the Remainers of the benefits of being part of a commercial bloc which is a real heavy weight on the world economic scene. This goes all the more so for the smaller EU member countries who, in addition, are devoid of the economic and political advantages which the British bourgeoisie can at least place its hopes on. There is also the fact that a number of populist governments have been made to consider how difficult leaving the EU can be because of the example of Britain – hence the EU’s uncompromising stance on the question. Another factor of the present resilience of the EU has been the concern of many of its member states about the successes of Russia in recent years. Germany, which does not dispose of the military might which would be needed to impose itself on the European continent, and is thus obliged to employ elements of collaboration and the search for common denominators in its attempt to develop its leadership, has responded to this by developing a foreign policy increasingly hostile towards Russia (with whom it could also have common interests). In the process, it is trying to get the celebrated Franco-German ‘motor’ going again, and to improve its strained relations with Poland.

It is evident that the evolution of the political crisis in London will be influenced by events not only in Europe but also in the United States. The radical Brexiteers (the likes of Farage, Cummings, Rees-Mogg) have little choice but to pin their hopes on the re-election of Trump 2020. But what if he isn´t re-elected? And even if he is, can the Brexiteers be sure that the man in the Oval Office might end up thinking that the break-up, not only of the EU, but also the UK might be in US interests?

Capitalism has always been, in a sense, a casino game, a gambling den, and London is one of its centres. Today, in the phase of capitalist decomposition, this is more than ever the case. A reckless game at the expense of the well-being and the future of humanity. When does this roulette game become a form of ‘Russian Roulette’? We will not even attempt to predict the outcome of the Brexit Game. Except that it will certainly not be to the benefit of the working class either in Britain or anywhere else in the world.

Steinklopfer. 06/08/2019.

Rubric:

Massive street protests in Hong Kong: Democratic illusions are a dangerous trap for the proletariat

- 798 reads

In the past month hundreds of thousands, even millions of the inhabitants of Hong Kong have engulfed the streets and squares in protest against an amendment to the Extradition Law [1], proposed by the Chief Executive of Hong Kong, Carrie Lam. The amendment would make it possible to extradite Hong Kong citizens to the mainland of China. The biggest rally against this amendment took place on 16 June, when nearly two million people gathered in a street protest.

The first protests in June were made possible by “The Civil Human Rights Front” (a coalition of more than fifty bourgeois organisations). This organisation was instrumental in making the June 9 and the June 12 rallies happen by getting the licenses to march and assemble. But the massive scale of the mobilizations was made possible via social media: people have organised their own initiatives, mainly through Facebook, Telegram groups, and the online forum lihkg.

Already on 31 March, an initial protest had taken place. A second demonstration was held on 28 April, attracting more than 100,000 protesters. Thereafter the movement gathered momentum, peaking during three different rallies on 9 and 12 and 21 June 2019, when millions of people entered into the street. On Monday 1 July, as Hong Kong marked the 22nd anniversary of its 1997 handover, the annual pro-democracy march still claimed a record turnout of half a million. [2]

The Hong Kong protests were not only aimed at the extradition law but, behind this, also at the growing attempts of the Chinese Stalinist regime to gain a more rigorous control over this former British colony. In order to understand these attempts of the Chinese state we must return to certain aspects of the past and the present of China. For China is passing through a more dangerous phase, given the developing economic crisis in China and elsewhere and the sharpening of the imperialist tensions.

The aggravation of China’s internal contradictions

Just as any other state in decadence of capitalism the Chinese state is weighed down by growing contradictions. China is a typical example of state capitalism that "takes on its most complete form where capitalism is subjected to the most brutal contradictions, and where the classical bourgeoisie is at its weakest." (International Review no. 34) Such a rigid political system is incompatible with any legal democratic opposition.

The regime in China cannot tolerate such oppositional forces without profoundly endangering itself. The Hong Kong movements of the last month have confronted the Beijing government one more time with the spectre of democracy.

In 1997 Hong Kong became an administrative region of China. Under the “one country, two systems” framework, the Chinese government guaranteed Hong Kong the right to retain its own social, legal and political systems for 50 years, until 2047.

But the existence of a semi-independent territory, in which anyone who is opposed to Beijing can find sanctuary, is like a tumor on the body of the Chinese state. Here the policy of “one country, two systems” shows its limits, being in fundamental contradiction with one-party rule. The “dual” system is prey to steady erosion, but the Chinese state cannot risk a second Tiananmen.

Centrifugal tendencies in China

In the period of decomposition, as the result of a stalemate in the class struggle between the bourgeoisie and the proletariat, the tendency towards each for himself increases dramatically and centrifugal forces tear apart nation states. The most obvious example was of course the collapse of the Eastern Bloc and the fragmentation of the former Soviet Union. But China is not spared from this centrifugal dynamic either. The resistance against the control of Beijing and the call for autonomy in the periphery continues and even seems to have become stronger in the recent years: Tibet, Xinjiang, Hong Kong, Macao, etc.

After the fall of the Quing Empire at the beginning of the 20th century, China fell apart into smaller political and territorial units. For a few decades, the country was fragmented and ruled over by competing warlords. When the Chinese Communist Party took power in 1949, it more or less re-established national unity. And if there is one thing the Stalinist Party cannot tolerate, then it is the call for autonomy by peripheral regions.

Before Xi Jinping took office in 2012 all 56 ethnic groups located in China had an equal status and could practice their own cultures and customs. But since then the “us against them” dichotomy, defined by antagonism and pointing at scapegoats, has gained strength in China. Even Taiwan has been not been spared. In January 2019 the Chinese President openly threatened Taiwan with annexation if this country did not yield and unite with the People’s Republic.

The deterioration of Chinese economy

China has also great problems on the economic level. Its actual growth is officially at 6.4 percent. But with a growing population and internal mobility of tens of millions who move from the countryside to the cities every year looking for a job, this figure is more a sign of a stagnant, even worsening economy.

Trump's trade war is also having a serious effect on the Chinese economy. In February 2019, China's exports showed the strongest decline in three years. Exports fell by 20.7 percent compared to the previous year, despite the government's huge stimulus measures. In 2018, a dramatic year for stock exchanges, the biggest losers could be found in China. The Shanghai Stock Exchange fell by 24.9 percent and the Dow Jones China by 24.7 percent.

In 2013 China launched a geo-strategic project of its own which, it hopes, will counter the worst effect of the crisis: the “New Silk Road”. But now China is even starting to have problems with its allies that joined this project in recent years. Several of these countries (Malaysia, Pakistan, Myanmar, Sri Lanka, etc.) are indebted at levels that are no longer sustainable.

The increased repression in all regions of the country.

Given the fact that the China state, by its very nature, is unable to tolerate democratic opposition it has to resort to repression in the face of any discontent. And with the growth of the centrifugal forces and the threat of social unrest, this repression over society has only increased. What we are witnessing is China at this moment is a kind of organised terror with the main aim to create a climate of fear. [3]

Beijing has increasingly deployed mass surveillance systems to tighten control over society. It collects, on a massive scale, biometrics including DNA and voice samples for automated surveillance purposes; developed a nationwide reward and punishment system known as the “social credit system”; and developed and applied “big data” policing programs aimed at preventing dissident voices.

The Chinese government has applied sweeping repression in different regions, in particular Xinjiang, home of the Muslim Uighur population. Since 2016, Chinese authorities have stepped up mass detention centers and prisons in this region. Outside these detention facilities the residents of Xinjiang are subjected to extraordinary restrictions on personal life: if they want to travel from one town or another, they have to apply for permission and to go through several checkpoints.

Even Hong Kong does not lag behind in this respect and applies similar measures in curtailing civil and political freedom. The state repression of the past four years had led to 50 trials, in which several hundred political dissidents and activists have been targeted for arrests and selected prosecution with various allegations, while over one hundred of them have been sent to jail.

Beijing’s tightening control on Hong Kong

Since 1997 China's ruling Party has gradually been exerting more influence over Hong Kong. In the past twenty years it has regularly changed the rules in a sense that responds to the need of the Chinese ruling class to strengthen its grip on Hong Kong politics. Every decision it takes and every step it makes is aimed at gaining a better control over this city.

The first large-scale protest against the growing influence of the Stalinist Party took place in 2003. The implementation of Basic Law Article 23 made it possible to convict people for treason, separatist activities, subversion of state power, and theft of state secrets. The second large-scale protest was in 2014, the so-called “Umbrella Revolution”, against the unilateral decision by the Chinese regime to screen candidates for the leadership of Hong Kong. [4]

In 2017 Chinese imperialism upped the ante further. On the eve of the 20th anniversary of the handover, the Chinese Foreign Ministry declared that the Sino-British Agreement, which guarantees independence of Hong Kong on political, juridical and economic matters until 2047, has become “a historical document, [which] no longer has any practical significance”.

The introduction of the new legislation (the amendment to the existing extradition bill), in February of this year, provoked a great concerns and anxiety among the citizens of Hong Kong about the increased risk to be sent to mainland China, where courts are under a rigorous control of the Stalinist state apparatus.

To understand why the protest took on such huge proportions we must keep in mind that nearly half of the population of Hong Kong consists of the second or the third generation who fled China. The moment the Maoist Party came into power, in 1949, millions of Chinese took flight. As many as 100,000 people fled to Hong Kong each month. By the mid-1950s, Hong Kong had increased its population from 500,000 to a staggering 2.2 million.

Therefore the proposal by the Hong Kong government, which puts inhabitants of Hong Kong at risk of deportation to China to stand trial in a despotic court system, really touched the nerve of millions of Hong Kong citizens. They know that, under the rule of the Stalinist Party, people certainly cannot expect due process, and will generally face false convictions. Like the Soviet Union in the 1930’s, China is well-known for its show trials against political opponents. [5]

Censorship and black-out of information

The traditional media are rigorously censored by the Chinese state. Above all since President Xi Jinping took power in 2012, China has launched an unprecedented crackdown on online freedom, submerging the internet in propaganda and punishing journalists who post messages that are detrimental to the system.

As the mass protests in Hong Kong might resonate across the border and trigger a chain reaction into the mainland of China, the Beijing regime ordered the Chinese censors to wipe out posts and photos from social media sites. Media outlets have been largely silenced, and as a result not many people in China know what has been happening in Hong Kong.

The mystification of democratic rights

No matter how massive they were and no matter how many workers participated in them, the street protests were not a manifestation of working class struggle. In Hong Kong the proletariat was not engaged in a struggle as an autonomous class. On the contrary: the workers of Hong Kong were completely overwhelmed by and drowned in a mass of citizens.

Many protesters were working class youngsters. But during the massive protests a large part of them fought for bourgeois demands and democratic rights. Even if we might salute the courage and the determination of the participants, the mass protests in Hong Kong are a great danger for the proletariat. Completely situated on the bourgeois terrain they cannot but reinforce the illusions in democracy. And the fact that the movement has gained a momentary victory – the amendment being suspended – only increased the illusions among the protesters in Hong Kong and its supporters around the world.

Leftist political organisations only reinforce these tendencies and illusions by encouraging the fight for democratic rights and freedom of speech. In the case of the protests in Hong Kong

- the socialists of “Alternative Socialiste” in Canada propagate for instance "the struggle for democratic rights and against the current authoritarian system, [of course] linked to the need to break down the power of the capitalists".

- the “International Committee of the Fourth International” (WSWS) emphasizes that “Reaching out to mainland Chinese is an important step in the struggle for democratic rights”.

Even if leftists connect the struggle for democratic rights with the struggle of the proletariat for “breaking down the power of the capitalists” (whatever that means), for the proletariat the struggle for democracy remains a trap, only binding it still more to its capitalist exploiters. The real antagonism within capitalist society is not between the dictatorship and democracy, but between the exploiting ruling class and the exploited working class. The latter has nothing to gain by the participation in the movement for bourgeois democratic rights, no matter how massive it is.

The storming and ransacking of the parliament

We reject any slogan put forward by the capitalist left calling for self-determination, for a democratic worker-led government, etc.

The same goes for the intrusion into the Legco (Legislative Council) on Monday night 1 July. After having forced entry, hundreds of protesters swarmed into the parliament building, tearing down portraits of legislative leaders and spray-painting pro-democracy slogans on the walls of the main chamber.

We do not support such pseudo-radical actions. On the contrary: not a single object smashed in a parliament is sufficient to smash the illusions in the parliamentary system. By ransacking, by looting places, by burning buildings of the state we do not break down illusions in parliamentarism. Actions motivated by democratic ideology only serve the interests of the bourgeois state.

This was shown by the fact that the events were immediately used to put the entire protest movement in a bad light. Chinese state media broadcasted no footage of the massive “peaceful” protest, but it did of the “serious illegal actions”, by “Hong Kong separatists” in which “blind arrogance and rage” dominated.

The smashing of illusions in parliament and democracy can only come through the autonomous action of the working class, in defence of its own class demands. The only way to fight against the false system of parliamentary representation is to hold proletarian mass assemblies, animated by serious discussion about the methods and aims of the struggle.

The hypocrisy of the Western democracies

The western states have expressed their support for the people of Hong Kong in their defence of democratic rights and freedom of expression.

On Monday 10 June US State Department spokeswoman, Morgan Ortagus, declared that “the United States shares the concern of many in Hong Kong that (…) the proposed amendments could undermine Hong Kong’s (…) human rights, fundamental freedoms and democratic values”. On Monday 1 July the British Foreign Secretary Jeremy Hunt said that “it is imperative that Hong Kong’s high degree of autonomy, and the rights and freedoms of the Hong Kong people are fully respected.”

But neither the United States nor the United Kingdom are any less hypocritical than China, and are far from being innocent regarding human rights violation as the following three examples clearly show.

(1) In China the western companies rely on the repression by the Chinese state to submit the Chinese workers to a system of extreme exploitation.

Hundreds of millions of Chinese workers must travel thousands of miles to seek job opportunities, often sleeping at the workplace in basic accommodation and only visiting their family once a year and that for a wage that is less than one-tenth of the average monthly wage in America. “In colluding with the government, employers squeeze the maximum labour within the shortest time possible from the workers.” (The Post Multi-Fibre Arrangement era and the rise of China, Au Loong-Yu)

Another factor is the policy of disciplining and repressing of the workers by means of the so-called “household registration system”. This system “acts as a kind of social apartheid, which systemically discriminates against migrant workers, barring them from enjoying public provisions in the cities. Outside the factories and dormitories, they simply cannot survive in the cities. It is an effective way to force them to accept starvation wages, appalling working conditions, and forced overtime.” (Idem)

(2) On their own national territory the western states detain refugees in the most horrible circumstances themselves.

Britain’s network of immigration removal centres are a real humiliation for the 25,000 migrants who pass through each year: there is no rehabilitation, no criminal sentence, inadequate healthcare, very often no time limit on the loss of liberty and overcrowded cells. Many of those incarcerated say that the conditions are far worse than actual prison, as they are physically and verbally abused by staff members, and this includes sexual and racist violence.

In the United States the Homeland Security inspector has found “dangerous overcrowding” and unsanitary conditions at a detention centre in Texas, where hundreds more migrants were being housed than the center was designed to hold. The inspector said that the cells “smelled of what might have been unwashed bodies/body odour, urine, untreated diarrhea, and/or soiled clothing/diapers”, (“Crammed into cells and forced to drink from the toilet – this is how the US treats migrants”, The Guardian, 3 July 2019)

(3) Just like the Chinese government the western ‘democracies’ also use super-intelligent technology to spy on civilians.

In the United States the CIA, via sophisticated hacking tools and software, uses everyday devices - from the phone in your pocket to the television set in your bedroom - to gather information on civilians. “Internal CIA documents (…) indicated the spy agency had gained access to Android and Apple smartphones, Samsung Smart TVs and Internet-enabled cars using a variety of tools.” (“CIA Uses Smart Devices to Spy on Citizens, WikiLeaks Reveals”, Marissa Lang, San Francisco Chronicle, March 8, 2017)

“At least 100 aircraft are being used by US law enforcement to spy on citizens. These aircraft are equipped with advanced, very high-resolution imaging and video technology — specifically Sting Ray, the secretive bulk cellular phone-tracking technology, and likely infrared or other night-vision hardware. The FBI has placed its eyes across the skies of the nation to mass surveil the public and spy on protesters.” (“Mass Surveillance and ‘Smart Totalitarianism’”; Chris Spannos, ROAR Magazine, February 18, 2017)

The trap of the Western support for democratic rights

The Western democracies are completely indifferent regarding human rights and the well-being of the people around the world. The same goes for the people of Hong Kong, which once was the most successful colony of Britain in the world. But when China became the main focus and more lucrative for the United Kingdom, Hong Kong was disposed of, in full knowledge that it would come under the yoke of a Stalinist regime.

Trump's administration and other western governments are content to work and conduct lucrative trade with a multitude of odious dictatorships around the world, including China. At the same time they are ready to utilise the defence of democratic rights and autonomy by the Hong Kong people as useful propaganda in their trade war against the same Chinese regime.

The protesters in Hong Kong, by waving American and British flags, show that the struggle against the Stalinist dictatorship on the bourgeois terrain of the democratic freedom, only leads them to embrace democratic dictatorship. The mobilisation of Hong Kong citizens is being used, by the United States and Great Britain in particular, for their sordid imperialist interests in the geopolitical confrontation against China.

Dennis

------------------------------

Notes

[1] Currently, Hong Kong is only obliged to extradite persons suspected of a crime on a case-by-case basis to 20 countries, under two main laws – the Fugitive Offenders Ordinance (FOO) and the Mutual Legal Assistance in Criminal Matters Ordinance – which expressly exclude “any other parts of the People’s Republic of China”. In February 2019 the Hong Kong government proposed to pass an amendment to the law for transfers of persons suspected of a crime not only for Taiwan and Macau, but also for mainland China.

[2] In the weeks thereafter the mobilisation decreased: Sunday 7 July, protesters came into the street in a mobilization of 250,000 and again on 14 July in demonstration of 100,000 people. But they have become more violent, notably after the intervention of triad gangsters against the demonstrators and increased police use of tear gas and systematic beatings.

[3] In China, anyone seen as a threat to the CCP can be “disappeared”. Some are held in secret prisons, while some are placed in detention centers under false names. Family, lawyers, and even China's state prosecutors are denied access.

[4] See the article “Hong Kong's ‘Umbrella Revolution’: soaked by democratic ideology”; ICCOnline, October 2014

[5] Many critics of Beijing rule, after being arrested, appear on CCTV, confessing to vague almost non-crimes, criticising themselves, or discrediting others. All this is symbolised by the 11-year prison sentence served on the Nobel Peace Prize winner Liu Xiaobo for advocating democracy. He was arrested in 2009 and sentenced to 11 years in prison.

Rubric:

Only the international class struggle can end capitalism’s drive towards destruction

| Attachment | Size |

|---|---|

| 209.16 KB |

- 702 reads

One of the more popular banners on climate change protests reads: “System Change, not Climate Change”.

There is no question that the present system is dragging humanity towards an environmental catastrophe. The material evidence piles up every day: increasingly dangerous heatwaves, unprecedented wildfires in the Amazon, melting glaciers, floods, extinction of whole species – with the extinction of the human species as the ultimate result. And even if global warming were not happening, the soil, the air, the rivers and seas would continue to be poisoned and depleted of life.

No wonder that so many people, and above so many young people who face a menacing future, are deeply concerned about this situation and want to do something about it.

The wave of protests organised by Youth for Climate, Extinction Rebellion, the Green parties and the parties of the left are presented as a way forward. But those who are currently following their lead should ask themselves: why are these protests being so widely supported by those who manage and defend the present system? Why is Greta invited to speak to parliaments, governments, the United Nations?

Of course the likes of Trump, Bolsonaro or Farage constantly vilify Greta and the “eco-warriors”. They claim that climate change is a hoax and that measures to curb pollution are a threat to economic growth, above all in sectors like automobiles and fossil fuels. They are the unabashed defenders of capitalist profit. But what about Merkel, Macron, Corbyn, Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez and others who have heaped praise on the climate protests: are they any less part of the present system?

Many of those taking part in the present protests would agree that the roots of ecological destruction lie in the system and that this is the capitalist system. But the organisations behind the protests, and the politicians who trumpet their hypocritical support for them, defend policies that hide the real nature of capitalism

Consider one of the main programmes the more radical among these politicians put forward: the so-called “New Green Deal”. It offers us a package of measures to be taken by the existing states, demanding massive capital investment to develop “non-polluting” industries that are supposed to be able to turn a decent profit. In other words: it’s framed entirely within the confines of the capitalist system. Like the New Deal of the 1930s, its aim is to save capitalism in its hour of need, not replace it.

What is the capitalist system?

Capitalism doesn’t disappear if it’s managed by state bureaucrats instead of private bosses, or if it paints itself green.

Capital is a world-wide relation between classes, based on the exploitation of wage labour and production for sale in order to realise profit. The constant search for outlets for its commodities calls forth ruthless competition between nation states for domination of the world market. And this competition demands that every national capital must expand or die. A capitalism that no longer seeks to penetrate the last corner of the planet and grow without limit cannot exist. By the same token, capitalism is utterly incapable of cooperating on a global scale to respond to the ecological crisis, as the abject failure of all the various climate summits and protocols has already proved.

The hunt for profit, which has nothing to do with human need, is at the root of the despoliation of nature and this has been true since capitalism began. But capitalism has a history, and for the last hundred years it has ceased to be a factor for progress and has been plunged into a profound historic crisis. It is a civilisation in decay, as its economic base, forced to grow without limit, generates crises of overproduction that tend to become permanent. And as the world wars and “Cold War” of the 20th century have demonstrated, this process of decline can only accelerate capital’s drive towards destruction. Even before the global massacre of nature became obvious, capitalism was already threatening to obliterate humanity through its incessant imperialist confrontations and wars, which are continuing today across a whole swathe of the planet from North Africa and the Middle East to Pakistan and India. Such conflicts can only be sharpened by the ecological crisis as nation states compete for dwindling resources, while the race to produce more and more nightmarish weapons – and above all, to use them - can only further pollute the planet. This unholy combination of capitalist devastation is already making parts of the planet uninhabitable and forcing millions to become refugees.

The necessity and possibility of communism

This system cannot overcome the economic crisis, the ecological crisis, or the drive towards war.

It is therefore a deception to demand that the governments of the world “get their act together” and do something to save the planet - a demand put forward by all the groups organising the current marches and protests. The only hope for humanity lies in the destruction of the present system and the creation of a new form of society. We call this communism - a world-wide human community without nation states, without the exploitation of labour, without markets and money, where all production is planned on a global scale and with the sole motive of satisfying human need. It goes without saying that this society has nothing in common with the state-run form of capitalism we see in countries like China, North Korea or Cuba, or previously the Soviet Union.

Authentic communism is the only basis for establishing a new relationship between humanity and the rest of nature. And it’s not a utopia. It’s possible because capitalism has laid down its material foundations: the development of science and technology, which can be freed from their distortions under this system, and the global interdependence of all productive activity, which can be freed from capitalist competition and national antagonisms.

But above all it’s possible because capitalism is based on the formation of a class with nothing to lose but its chains, a class which has an interest both in resisting exploitation and overthrowing it: the international working class, the proletariat of all countries. This is a class which includes not only those who are exploited at work but also those studying to find a place in the labour market and those whom capital throws out of work and on to the scrap-heap.

Citizens’ protests or workers’ struggle?

And it is here in particular that the ideology behind the climate marches serves to prevent us from grasping the means to fight against this system. It tells us, for example, that the world is in a mess because the “older generation” got used to consuming too much. But talking about generations “in general” obscures the fact that, yesterday and today, the problem lies with the division of society into two main classes, one, the capitalist class or bourgeoisie, which has all the power, and one far larger class which is exploited and deprived of all power of decision, even in the most “democratic” of countries. It’s the impersonal mechanisms of capital that have got us into the current mess, not the personal behaviour of individuals or the greed of a previous generation.

The same goes for all the talk about the “people” or the “citizens” as the force that can save the world. These are meaningless categories which cover up antagonistic class interests. The way out of a system which cannot exist without the exploitation of one class by another can only take place through the revival of the class struggle, which starts with workers defending their most basic interests against the attacks on living and working conditions inflicted by all governments and all bosses in response to the economic crisis – attacks which are also more and more being justified in the name of protecting the environment. This is the only basis for the working class developing a sense of its own existence against all the lies which tell us that it’s already an extinct species. And it’s the only basis for the class struggle fusing the economic and political dimensions - drawing the link between economic crisis, war, and ecological disaster, and recognising that only a world-wide revolution can overcome them.

In the lead-up to the First World War, hundreds of thousands marched in pacifist demonstrations. They were encouraged by the “democratic” ruling classes because they spread the illusion that you could have a peaceful capitalism. Today the illusion is being spread far and wide that you can have a green capitalism. And again: pacifism, with its appeal to all good men and true, hid the fact that only the class struggle can really oppose war – as it proved in 1917-18, when the outbreak of the Russian and German revolutions obliged the rulers of the world to bring the war to a rapid close. Pacifism has never stopped wars, and the current ecological campaigns, by peddling false solutions to the climate disaster, must be understood as an obstacle to its real solution.

International Communist Current

27 August 2019

A PDF version, which can be downloaded and distributed is now attached

Rubric:

The hidden legacy of the left of capital (III): a functioning which negates communist principles

- 472 reads

This series has denounced the least visible part (the hidden face) of the organisations of the left and extreme-left of capital (Socialists, Stalinists, Trotskyists, Maoists, official anarchism, the 'new' left of Syriza, France Insoumise, and Podemos). In the first article of the series we saw how these organisations negate a working class that they pretend to defend, in the second we unravelled their method and way of thinking. In this third article we want to analyse their functioning, the internal regimes of these parties and how their functioning is the very negation of all communist principles and constitutes an obstacle to any movement towards these principles.

The forces of Stalinism, Trotskyism, etc., have carried out a total falsification of proletarian positions in terms of their organisation and behaviour. For them, centralisation means submission to an all-powerful bureaucracy, and discipline is blind submission to a control commission. The majority position is the result of a power struggle. And debate, in the spirit of manipulation, is a weapon to overcome the position of rival gangs. And so we could continue ad nauseam.

It's possible that a proletarian militant inside a genuinely communist organisation could have a tendency to see its organisational positions and behaviour through the lenses of the grim times that they spent in one or other leftist organisation.

The discipline of the barracks of leftist organisations

When we talk to this hypothetical militant of the need for discipline, they remember the nightmare that they lived through when they were a member of an organisation of the bourgeois left.

In those organisations, 'discipline' means defending absurd things because 'the party demands it'. One day they have to say that a rival part was 'bourgeois' and the following week, according to political changes in the alliances of the leadership, this part is now the most proletarian in the world.

If the policy of the central committee is wrong it is solely the fault of the militants who have 'made an error' and 'have not correctly applied what the central committee had decided'. As Trotsky said: "Each resolution of the Executive Committee of the Communist International recording new defeats declared on one hand that everything had been planned and that, on the other hand, it's the fault of those who interpreted it because they hadn't understood the line given to them from above"[1].

Following these traumatic experiences, the militant who has been through these parties feels a visceral rejection of discipline, not understanding that proletarian discipline is something radically different and opposed to the discipline of the bourgeoisie.