International Review No 163 - Winter 2019

- 282 reads

"Popular revolts" are no answer to world capitalism's dive into crisis and misery

- 470 reads

Throughout the world attacks against the working class have widened and deepened[1]. And it's always on the backs of the working class that the dominant class tries to minimise the effects of the historic decline of its own mode of production. In the "rich" countries, planned job losses in the near future are piling up, particularly in Germany and Britain. Some so-called "emergent" countries such as Brazil, Argentina, Turkey, are already in recession with all that this implies for the aggravation of the living conditions of the proletariat. As to the countries that are neither "rich" nor "emergent", their situation is even worse. The non-exploiting elements in these places are plunged into an endless misery.

These latter countries particularly have recently been the theatre of popular movements against the endless sacrifices demanded by capitalism and implemented by governments which are often gangrened by corruption, discredited and hated by the population. Such movements have taken place in Chile, Ecuador, Haiti, Iraq, Iran, Algeria and Lebanon. These frequently massive mobilisations are, in some countries, accompanied by the unleashing of violence and bloody repression. The widescale movement in Hong Kong, which has developed not in reaction to misery and corruption, but to the hardening of the state’s repressive arsenal - particularly regarding extraditions to mainland China - has recently witnessed a new level of repression: the police have started firing live ammunition at the demonstrators.

If the working class is present in these "popular revolts", it's never as an antagonistic class to capital but one drowned within the population. Far from favouring a future riposte from the working class and, with it, the only viable perspective of a struggle against the capitalist system, these popular, inter-classist revolts serve to reinforce the idea of "no future", which can only obscure such a perspective. They strengthen the difficulties experienced by the working class in mounting its own response to the more and more intolerable conditions that are the result of the bankruptcy of capitalism. Nevertheless, the contradictions of this system cannot be eliminated and will become ever deeper, pushing the world working class to confront all the difficulties that it is presently undergoing.

Exasperation faced with the plunge into yet more misery

After years of repeated attacks, it's often an innocuous price rise that "sparks off the explosion".

In Chile, it was the fare increase on the Metro which was the final straw: "The problem is not the 30 centimes" (increase), "it is the 30 years" (of attacks), according to a slogan from a demonstrator. Monthly wages are below 400 euros in this country; precarious working is very widespread; costs of basic necessities are disproportionally high and the health and education sectors are failing, while to retire is to be condemned to poverty.

In Ecuador, the movement was provoked by a sudden increase in fares. This follows a list of price increases in basic goods and services, the freezing of wages, massive redundancies, an obligation to give a day's work "free" to the state, the reduction of days off and other measures leading to precarious working and a deterioration of living conditions.

In Haiti, fuel shortages hit the population as a supplementary catastrophe, leading to a general state of paralysis in what has long been one of the poorest countries in the region.

If the economic crisis in general is the main cause of the attacks against living conditions, they overlap in some countries such as Lebanon, Iraq and Iran, with the traumatising and dramatic consequences of imperialist tensions and the endless wars ravaging the Middle East.

In Lebanon, it was the imposition of a tax on WhatsApp calls which provoked the revolt in a country with the highest debt per person in the world. Each year the government imposes new taxes, a third of the population are unemployed and the infrastructure of the country is second-rate. In Iraq, where the movement broke out spontaneously following calls on social media, the protesters demanded jobs and functioning public services while expressing their rage against a ruling class that they accuse of being corrupt. In Iran, the hike in fuel prices comes on top of a situation of profound economic crisis, aggravated by US sanctions on the country.

The impotence of these movements; the repression and manoeuvres of the bourgeoisie

In Chile, attempts of struggle have been diverted onto the barren grounds of a nihilist violence which is characteristic of capitalist decomposition. Favoured by the state, we've also seen eruptions of lumpen elements in minority and irrational acts of violence. This climate of violence has been well-used by the state in order to justify its repression and intimidate the proletariat. The official figures are 19 dead but like official figures everywhere, they greatly underestimate the slaughter. As in the worst times of Pinochet, torture has made its reappearance. But the Chilean bourgeoisie realised that brutal repression wasn't enough to calm the growing discontent. So the Pinera government held its hands up, adopted a "humble" posture and said that it "understood" the "message of the people", that it would "provisionally" withdraw the increases and open the door to a "social consultation". That's to say that the attacks will be imposed by "negotiation" from a table of "dialogue" around which will sit the opposition parties, the unions, the bosses - all "representing the nation" together[2].

In Ecuador, transport associations have paralysed traffic and the indigenous movement, together with other diverse groups, have joined the demonstrations. The protests of self-employed drivers and small business people take place as expressions of the "citizens" and are dominated by nationalism. It's in this context that the initial mobilisation of workers against the attacks - in the south of Quito, Tulcan and in the Bolivar province - constitute a compass for action and reflection faced with the surge in the mobilisation of the petty bourgeoisie.

The Republic of Haiti is in a situation close to paralysis. Schools are closed, the main roads between the capital and the regions are cut off by roadblocks, and numerous businesses have closed. The movement is often accompanied by violence while criminal gangs (among the 76 armed gangs reported in the territory at least 3 are in the pay of the government, the rest are under the control of an old deputy and some opposition senators), engage in abuses, blocking roads and hi-jacking rare cars. On Sunday October 27, a vigilante opened fire on protesters, killing one; he was lynched and burnt alive. Official figures put the number of deaths at twenty over two months.

Algeria. A human tide has again taken to the streets of Algiers on the anniversary of the beginning of the war against French colonisation. The movement is similar to that recorded at the heights of the "Hirak", a protest movement which has been taking place in Algeria since February 22. It is massively opposed to the general election proposed by the government and organised for December 12 in order to elect a successor to Bouteflika, with the aim of "regenerating" the system.

Iraq. In several provinces of the south, protesters have attacked the institutions and buildings of the political parties and armed groups. Public workers, trade unionists, students and schoolchildren, have demonstrated and begun sit-ins. While, according to the latest official figures, the repression has caused the deaths of 239 people, the majority hit by live ammunition, mobilisations have continued in Baghdad and the south of the country. Since the beginnings of the outburst, protesters have maintained that they will refuse any political recuperation of their movement because they want to totally renew the political class. They also say that it's necessary to do away with the complicated system of awarding posts by faith or ethnicity, a process eaten away by clientism - and one steeped in corruption - that excludes the majority of the population and young people in particular. Just recently, there have been massive jubilant demonstrations and strike pickets have paralysed universities, schools and administration. Elsewhere, nocturnal violence has been directed at the headquarters of the political parties and the militias.

Lebanon. General popular anger has transcended communities, faiths and all the regions of the country. The withdrawal of the new tax on Whatsapp calls has not prevented the revolt from spreading to the whole of the country. The resignation of Prime Minister Saad Hariri was only a small part of the population's demands. They are demanding the departure of the whole of the political class who they judge as corrupt and incompetent while demanding a radical change of the system.

Iran. As soon as the price increases in fuel were announced, violent confrontations between protesters and the forces of order took place, leading to deaths on both sides but particularly numerous on the side of the former.

The trilogy of inter-classism, democratic demands, and blind violence

In all these inter-classist, popular revolts quoted above and according to the information that we have to hand, the proletariat has only shown itself as a class in a minority way here and there, including in a situation like Chile where the prime cause of the mobilisations was clearly the necessity for defence against the economic attacks.

Often, even exclusively, the "revolts" take their aim at the privileged, those in power who are judged responsible for all the ills overwhelming the populations. But in this way, they leave out the system of which the privileged are just the servants. To focus the struggle on the fight to replace corrupt politicians is obviously an impasse because, whatever the teams in power, whatever their levels of corruption, all of them can only defend the interests of the bourgeoisie and implement policies in the service of a capitalism in crisis. It is a much more dangerous impasse in that it's somewhat legitimised by democratic demands "for a clean system", whereas democracy is the privileged form of the power of the bourgeoisie for maintaining its class domination over society and the proletariat. It's significant in this regard that in Chile, after the ferocious repression and faced with an explosive situation that the bourgeoisie had underestimated, it then passed onto a new phase of its manoeuvres through a political attack by setting up classic democratic organisms of mystification and isolation, ending up in the plan for a "new constitution" which is presented as a victory for the protest movement.

Democratic demands dilute the proletariat into the whole of the population, blurring the consciousness of its historic combat, submitting it to the logic of capitalist domination and reducing it to political impotence.

Inter-classism and democracy are two methods which marry up and complement each other in a terribly efficient way against the autonomous struggle of the working class. This is much more the case over the last few decades, since with the collapse of the eastern bloc and the lying campaigns on the death of communism[3], the historic project of the proletariat has temporarily ceased to underlie its struggle. When the latter manages to impose itself, it will be against the current of the general phenomenon of the decomposition of society where each for themselves, the absence of perspectives, etc., acquire an accrued weight.

The rage and violence which often accompanies these popular revolts are far from expressing any sort of radicalism. That's very clear when it's carried out by lumpen elements, whether acting spontaneously or given the nod and wink by the bourgeoisie, and engaging in vandalism, pillages, arson, irrational and minority violence. But, more fundamentally, such violence is intrinsically contained in popular movements where the institutions of the state are not directly called into question. Having no perspective for the radical transformation of society, abolishing war, poverty, growing insecurity and the other calamities of a dying capitalism, movements that end up in this impasse can’t avoid spreading all the defects of a decomposing capitalist society.

The degenerating protest movement in Hong Kong constitutes a perfect example of this in the sense that, more and more deprived of any perspective - in fact it can't have any, confined as it is to the "democratic" terrain without calling capitalism into question - it has turned itself into a giant vendetta of the protesters faced with police violence, and then the cops reply, sometimes spontaneously, to the violence they face. This is so clear that some elements of the bourgeois press have commented on it: "nothing that Beijing has done has worked, not the withdrawal of the extradition law, or police repression, or the ban on wearing face-masks in public. Henceforth, the youth of Hong Kong are no longer moved by hope but by the desire to do battle in the absence of any other possible outcome"[4].

Some people imagine, or want us to think, that any violence in this society which is exercised against the forces of state repression should be supported because it's similar to the necessary class violence of the proletariat against capitalist oppression and exploitation[5]. This shows a real contempt for the working class and it's a gross lie. In fact the blind violence of these inter-classist movements has nothing to do with the class violence of the proletariat which is a liberating force for the suppression of exploitation of man by man. By contrast, the violence of capitalism is oppressive, and has the primary aim of defending class society. The violence the inter-classist movement carries with it, in the image of the petty-bourgeoisie, has no future of its own. This is a class that can only go nowhere by itself and must end up rallying behind either the bourgeoisie or the proletariat.

In fact the trilogy of "inter-classism, democratic demands, blind violence" is the trademark of the popular revolts which are hatching out all over the planet in reaction to the accelerated degradation of all the living conditions which affect the working class, other non-exploitative layers and the pauperised petty-bourgeoisie. The movements of the "gilets jaunes" that started in France a year ago squarely falls into this category of popular revolts[6]. Such movements only contribute to obscuring the real nature of class struggle in the eyes of the proletariat, reinforcing its present difficulties in seeing itself as a class of society, distinct from other classes and with its specific combat against exploitation and its historic mission of overthrowing capitalism.

It's the reason why the responsibilities of revolutionaries and the most conscious minorities within the working class is to work for the re-appropriation of its own methods, at the heart of which figures the mass struggle; general assemblies as places of discussion and decisions while defending themselves against sabotage by the unions and open to all sectors of the working class; extension to other sectors imposed against the manoeuvres of division and control practised by the unions and the left of capital [7]. Even if today these perspectives seem far away, and that is the case in most parts of the world, particularly where the working class is in the minority with a limited historical experience, these methods nevertheless constitute the only way forward, the only means of allowing the proletariat to recover its class identity and not get lost along the way.

Silvio. (17.11.2019)

[1] Read our article "New recession: capitalism demands more sacrifices from the working class", https://en.internationalism.org/content/16738/new-recession-capital-dema... [2]

[2] For more information and analysis on Chile, see our article: https://en.internationalism.org/content/16762/dictatorshipdemocracy-alte... [3]

[3] We will come back soon in our press on the considerable impact of these lying campaigns on the class struggle and show what the state of the world really is today, in contrast to all the announcements about a new era of "peace and prosperity" at the beginning of the 1990s.

[4] "The Hong-Kong protesters aren't driven by hope". The Atlantic.

[5] From this point of view, it is illuminating to compare the recent revolts in Chile with the struggles of workers of the Argentinean Cordobazo in 1969 and we recommend this article: https://en.internationalism.org/content/16757/argentinean-cordobazo-may-... [4]

[6] See our account of this movement: https://en.internationalism.org/content/16748/yellow-vests-france-inter-... [5]

[7] Regarding this read: https://en.internationalism.org/content/16703/resolution-balance-forces-... [6]

Rubric:

Turkish invasion of northern Syria - the cynical barbarity of the ruling class

- 458 reads

Syrian Kurds throw potatoes at departing US troops

Trump’s telephone call to Erdogan on October 6 gave the “green light” for a major Turkish invasion of Northern Syria and a brutal clean-up operation against the Kurdish forces who have up till now controlled the area with US backing. It provoked a storm of outrage both among the USA’s NATO “allies” in Europe and large parts of the military and political establishment in Washington, most notably from Trump’s own former defence secretary “Mad Dog” Mattis. The principal criticism of Trump’s abandonment of the Kurds has been that it will undermine all credibility in the US as an ally you can rely on: in short, that it’s a disaster on the diplomatic level. But there is also the concern that the retreat of the Kurds will result in a revival of the Islamic Forces whose containment has been almost solely the work of the Kurdish forces supported by US air power. The Kurds have been holding thousands of IS prisoners, and more than a hundred of them have already broken out of gaol[1].

Trump’s action has set off alarm bells among significant parts of the US bourgeoisie, multiplying worries that his unpredictable and self-serving style of presidency is becoming a real danger for the US, and even that he is losing what little mental stability he possesses under the pressure of the office and above all of the current impeachment campaign against him. Certainly his behaviour is becoming increasingly bizarre, showing himself not only as an ignoramus (the Kurds didn’t support us on the Normandy landings…) but as a common mobster (his letter to Erdogan warning him not to be a fool or a tough guy, which the Turkish leader promptly threw in the bin, his threats to destroy Turkey’s economy…). He governs by tweet, takes impulsive decisions, disregards advice from his staff and then has to back-track the next minute – as witness the letter and the hasty dispatch of Pence and Pompeo to Ankara to cobble together a cease-fire in Northern Syria

But let’s not dwell too much on the personality of Trump. In the first place, he is merely an expression of the advancing decomposition of his class, a process which is everywhere giving rise to “strong men” who incite the lowest passions and rejoice in their disregard for truth and the traditional rules of the political game, from Duterte to Oban and from Modi to Boris Johnson. And even if Trump jumped the gun in his dealings with Erdogan, the policy of troop withdrawal from the Middle East was not the invention of Trump, but goes back to the Obama administration which recognised the total failure of US Middle East policy since the early 90s and the necessity to create a “pivot” in the Far East in order to counter the growing threat of Chinese imperialism.

The last time the US gave a green light in the Middle East was in 1990 when the US ambassador April Glaspie let it be known that the US would not interfere if Saddam Hussein marched into Kuwait. It was a well-organised trap, laid with the idea of conducing a massive US operation in the area and compelling its western partners to join a grand crusade. This was a moment when, following the collapse of the Russian bloc in 1989, the western bloc was already beginning to unravel and the US, as the only remaining super-power, needed to assert its authority by a spectacular demonstration of force. Guided by an almost messianic “Neo-Con” ideology, the first Gulf war was followed by further US military adventures, in Afghanistan in 2001 and Iraq in 2003. But the waning support to these operations from its former allies, and above all the utter chaos they stirred up in the Middle East, trapping US forces in unwinnable conflicts against local insurgencies, has demonstrated the steep decline of the USA’s ability to police the world. In this sense, there is a logic behind Trump’s impulsive actions, supported by considerable sectors of the American bourgeoisie, who have recognised that the US cannot rule the Middle East through putting boots on the ground or even through its own air power. It will rely more and more on its most dependable allies in the region – Israel and Saudi Arabia – to defend its interests through military action, directed in particular against the rising power of Iran (and, in the longer term, against the potential presence of China as a serious contender in the region).

The “betrayal” of the Kurds

The ceasefire negotiated by Pence and Pompeo – which Trump claims will save “millions of lives” – does not seriously alter the policy of abandoning the Kurds, since its aim is merely to give Kurdish forces the opportunity to retreat while the Turkish army asserts its control of northern Syria. And it should be said that this kind of “betrayal” is nothing new. In 1991, in the war against Saddam Hussein, the US under Bush Senior encouraged the Kurds of northern Iraq to rise up against Saddam’s regime – and then left Saddam in power, willing and able to crush the Kurdish uprising with the utmost savagery. Iran has also tried to use the Kurds of Iraq against Saddam. But all the powers of the region, and the global powers who stand behind them, have consistently opposed the formation of a unified state of Kurdistan, which would mean the break-up of the existing national arrangements in the Middle East.

The armed Kurdish forces, meanwhile, have never hesitated to sell themselves to the highest bidder. This is happening before our eyes: the Kurdish militia immediately turned to Russia and the Assad regime itself to protect them from the Turkish invasion.

Furthermore, this has been the fate of all “national liberation” struggles since at least the First World War: they have only been able to prosper under the wing of one or another imperialist power. The same grim necessity applies throughout the Middle East in particular: the Palestinian national movement sought the backing of Germany and Italy in the 1930s and 40s, of Russia during the Cold War, of various regional powers in the world disorder unleashed by the collapse of the bloc system. Meanwhile, the dependency of Zionism on imperialist support (mainly, but not only, from the US) needs no demonstration, but is no exception to the general rule. National liberation movements may adopt many ideological banners – Stalinism, Islamism, even, as in the case of the Kurdish forces in Rojava, a kind of anarchism – but they can only trap the exploited and the oppressed in the endless wars of capitalism in its epoch of imperialist decay[2] [8].

A perspective of imperialist chaos and human misery

The most obvious beneficiary from the US retreat from the Middle East has been Russia. During the 1970s and 80s, the USSR had been forced to renounce most of its positions in the Middle East, particularly its influence in Egypt and above all its attempts to control Afghanistan. Its last outpost, and a vital point of access to the Mediterranean, was Syria and the Assad regime, which was threatened with collapse by the war which swept the country after 2011 and the advances made by the “democratic” rebels and above all by Islamic State. Russia’s massive intervention in Syria has saved the Assad regime and restored its control to most of the country, but it is doubtful whether this would have been possible if the US, desperate to avoid getting stuck in another quagmire after Afghanistan and Iraq, had not effectively ceded the country to the Russians. This has sown major divisions in the US bourgeoisie, with some of its more established factions in the military apparatus still deeply suspicious of anything the Russians might do, while Trump and those behind him have seen Putin as a man to do business with and above all a possible bulwark against the seemingly inexorable rise of China.

Part of Russia’s ascent to such a commanding position in Syria has involved developing a new relationship with Turkey, which has gradually been distancing itself from the US, not least over the latter’s support for the Kurds in its operation against IS in the north of Syria. But the Kurdish issue is already creating difficulties for the Russian-Turkish rapprochement: since a part of the Kurdish forces are now turning to Assad and the Russians for protection, and as the Syrian and Russian military move in to occupy the areas previously controlled by the Kurdish fighters, there is a looming risk of confrontation between Turkey on the one hand and Syria and its Russian backers on the other. For the moment this danger seems to have been averted by the deal made between Erdogan and Putin in Sochi on 22 October. The agreement gives Turkey control over a buffer zone in northern Syria at the expense of the Kurds, while confirming Russia’s role as the main power-broker in the region. Whether this arrangement will overcome the long-standing antagonisms between Turkey and Assad’s Syria remains to be seen. The war of each against all, a central feature of imperialist conflict since the demise of the bloc system, is nowhere more clearly illustrated than in Syria.

For the moment Erdogan’s Turkey can also congratulate itself on its rapid military progress in northern Syria and the cleaning out of the Kurdish “terrorist nests”. The incursion has also come as a godsend to Erdogan at the domestic level: following some severe set-backs for his AKP party in elections over the last year, the wave of nationalist hysteria stirred up by the military adventure has split the opposition, which is made up of Turkish “democrats” and the Kurdish HDP

Erdogan can, for the moment, go back to selling the dream of a new Ottoman empire, Turkey restored to its former glory as a global player before it became the “sick man of Europe” at the beginning of the 20th century. But marching into what is already a profoundly chaotic situation could easily be a dangerous trap for the Turks in the longer run. And above all, this new escalation of the Syrian conflict will add considerably to its already gigantic human cost. Well over 100,000 civilians have already been displaced, greatly increasing Syria’s internal refugee nightmare, while a secondary aim of the invasion is to dump around 3 million Syrian refugees, currently living in dire conditions in Turkish camps, in northern Syria, largely at the expense of the local Kurdish population.

The baseless cynicism of the ruling class is revealed not only in the mass murder its aircraft, artillery and terrorist bombs rain on the civil population of Syria, Iraq, Afghanistan, or Gaza, but also by the way it uses those forced to flee from the killing zones. The EU, that paragon of democratic virtue, has long relied on Erdogan to act as a prison guard to the Syrian refugees under his “protection”, preventing them from adding to the waves heading towards Europe. Now Erdogan sees a solution to this burden in the ethnic cleansing of northern Syria, and threatens – if the EU criticises his actions – to channel a new refugee tide towards Europe.

Human beings are only of use to capital if they can be exploited or used as cannot fodder. And the open barbarism of the war in Syria is only a foretaste of what capitalism has in store for the whole of humanity if it is allowed to continue. But the principal victims of this system, all those whom it exploits and oppresses, are not passive objects, and in the past year or so we have glimpsed the possibility of mass reactions against poverty and ruling class corruption in social revolts in Jordan Iran, Iraq and most recently Lebanon. These movements tend to be very confused, infected by nationalist illusions, and cry out for a clear lead from the working class acting on its own class terrain. But this is a task not only for the workers in the Middle East, but for the workers of the world, and above all for the workers of the old centres of capital where the autonomous political tradition of the proletariat was born and has the deepest roots.

Amos, 23.10.19

[1] It is of course possible that Trump is quite relaxed about Islamic state forces regaining a certain presence in Syria, now that the Russians and the Turks are the ones who will be forced to deal with them. Similarly he seemed quite happy for the Europeans to be saddled with the problem of former IS fighters returning to their European countries of origin. But such ideas will not go unopposed within the US ruling class.

[2] [9] For further analysis of the history of Kurdish nationalism, see https://en.internationalism.org/icconline/201712/14574/kurdish-nationalism-another-pawn-imperialist-conflicts [10]

Rubric:

100 years after the foundation of the Communist International: What lessons can we draw for future combats? (part II)

- 305 reads

In the first part of this article, we recalled the circumstances in which the Third International (Communist International) was founded. The existence of the world party depended above all on the extension of the revolution on a global scale, and its capacity to assume its responsibilities in the class depended on the way in which the regroupment of revolutionaries from which it arose was carried out. But, as we showed, the method adopted in the foundation of the Communist International (CI), favouring the largest number rather than the clarification of positions and political principles, had not armed the new world party. Worse, it made it vulnerable to rampant opportunism within the revolutionary movement. This second part aims to highlight the content of the fight waged by the left fractions against the political line of the CI to retain old tactics made obsolete by the opening of capitalism’s decadent phase.

This new phase in the life of capitalism demanded a redefinition of certain programmatic and organisational positions to enable the world party to orient the proletariat on its own class terrain.

1918-1919: revolutionary praxis challenges old tactics

As we pointed out in the first part of this article, the First Congress of the Communist International had highlighted that the destruction of bourgeois society was fully on the agenda of history. Indeed, the period 1918-1919 saw a real mobilisation of the whole world proletariat,[1] firstly in Europe:

- March 1919: proclamation of the Republic of Councils in Hungary

- April-May 1919: episode of the Republic of Councils in Bavaria

- June 1919: attempts at insurrection in Switzerland and Austria.

The revolutionary wave then spread to the American continent:

- January 1919: “bloody week” in Buenos Aires, Argentina, where workers are savagely repressed.

- February 1919: strike in the shipyards in Seattle, USA, which eventually extends to the entire city in a few days. The workers manage to take control of supplies and defence against troops sent by the government.

- May 1919: general strike in Winnipeg, Canada.

But also Africa and Asia:

- In South Africa, in March 1919, the tramway strike spreads throughout Johannesburg, with assemblies and rallies in solidarity with the Russian Revolution.

- In Japan, in 1918, the famous “rice meetings” take place against the shipment of rice to Japanese troops sent against the revolution in Russia.

Under these conditions, revolutionaries of the time had real reasons to say that “The victory of the proletarian revolution on a world scale is assured. The founding of an international Soviet republic is underway”.[2]

So far, the extension of the revolutionary wave in Europe and elsewhere confirmed the theses of the First Congress:

“1) The present epoch is the epoch of the disintegration and collapse of the entire capitalist world system, which will drag the whole of European civilization down with it if capitalism, with its insoluble contradictions, is not destroyed.

2) The task of the proletariat now is to seize state power immediately. The seizure of state power means the destruction of the state apparatus of the bourgeoisie and the organization of a new apparatus of proletarian power.”[3]

The new period that was opening up, of wars and revolutions, confronted the world proletariat and its world party with new problems. The entry of capitalism into its decadent phase directly posed the necessity of the revolution and modified somewhat the form which the class struggle was to take.

The formation of left currents within the CI

The revolutionary wave had consecrated the finally found form of the dictatorship of the proletariat: the soviets. But it had also shown that the forms and methods of struggle inherited from the 19th century, such as trade unions or parliamentarism, were now over.

“In the new period it was the practice of the workers themselves that called into question the old parliamentary and unionist tactics. The Russian proletariat dissolved parliament after it had taken power and in Germany a significant mass of workers pronounced in favour of boycotting the elections in December 1918. In Russia as in Germany, the council form appeared as the only form for the revolutionary struggle, replacing the union structure. But the class struggle in Germany had also revealed an antagonism between the proletariat and the unions.”[4]

The rejection of parliamentarism

The left currents in the International organised themselves on a clear political basis: the entry of capitalism into its decadence phase imposed a single path; that of the proletarian revolution and the destruction of the bourgeois state with a view to abolishing social classes and constructing a communist society. From now on, the struggle for reform and revolutionary propaganda in bourgeois parliaments no longer made sense. In many countries, for the left currents the rejection of elections became the position of a true communist organisation:

- In March 1918, the Polish Communist Party boycotts the elections.

- On 22 December 1918 the organ of the Abstentionist Communist Fraction of the Italian Socialist Party (PSI), Il Soviet, is published in Naples under the leadership of Amedeo Bordiga. The Fraction sets out its goal as being to “eliminate the reformists from the party in order to ensure for it a more revolutionary attitude”. It also insists that “all contact must be broken with the democratic system”; a true communist party is possible only “if we renounce electoral and parliamentary action.”[5]

- In September 1919, the Workers’ Socialist Federation speaks out against “revolutionary parliamentarism”.

- The same is true in Belgium for De Internationale in Flanders and the Communist Group of Brussels. Antiparliamentarianism is also defended by a minority of the Bulgarian Communist Party, by part of the group of Hungarian Communists exiled in Vienna, by the Federation of Social Democratic Youth in Sweden and by a minority of the Partido Socialista Internacional of Argentina (the future Communist Party of Argentina).

- The Dutch remain divided on the parliamentary question. A majority of the Tribunists are in favour of the elections; the minority like Gorter is indecisive, while Panekoek defends an antiparliamentary position.

- The KAPD was also opposed to participation in elections.

For all these groups, the rejection of parliamentarism was now a matter of principle. This was actually putting into practice the analyses and conclusions adopted at the First Congress. But the majority of the CI did not see it that way, starting with the Bolsheviks; even if there was no ambiguity about the reactionary nature of trade unions and bourgeois democracy, the fight within them should not be abandoned. The circular of the Executive Committee of the CI of 1 September 1919 endorsed this backward step, returning to the old social democratic conception of making parliament a place of revolutionary conquest: “[militants] go into parliament in order to appropriate this machinery and to help the masses behind the Parliamentary walls to blow it up.”[6]

The trade union question crystallises the debates

The first episodes of the revolutionary wave quoted above had clearly shown that the unions were obsolete organs of struggle; worse, they were now against the working class.[7] But more than anywhere else, it was in Germany that this problem was posed in the most crucial way and where revolutionaries managed to establish the clearest understanding of the need to break with trade unions and trade unionism. For Rosa Luxemburg, the unions were no longer “workers’ organisations, but the strongest protectors of the state and of bourgeois society. Therefore, it goes without saying that the struggle for socialisation cannot be carried out without involving the struggle for the liquidation of trade unions”.[8]

The leadership of the CI was not so far-sighted. Although it denounced the unions dominated by social democracy, it still retained the illusion of being able to reorient them on a proletarian path:

“What is now to happen to the trade unions? Along what path will they travel? The old union leaders will again try to push the unions onto the bourgeois road [...] Will the unions continue along this old reformist road? [...] We are deeply convinced that the answer will be no. A fresh wind is blowing through the musty trade union offices. [...] It is our belief that a new trade union movement is being formed.”[9]

It was for this reason that in its earliest days the CI accepted into its ranks national and regional unions of trades or industries. In particular, there were revolutionary syndicalist elements such as the IWW. If the latter rejected both parliamentarism and activity in the old unions, it remained hostile to political activity and therefore to the need for a political party of the proletariat. This could only reinforce the confusion within the CI on the organizational question since it included groups that were already “anti-organisation”.

The most lucid group on the trade union question remained without doubt the left-wing majority of the KPD which was to be excluded from the party by the leadership of Levi and Brandler. It was not only against unions in the hands of the social democrats but hostile to any form of trade unionism such as anti-political revolutionary syndicalism and anarcho-syndicalism. This majority was to found the KAPD in April 1920, whose programme clearly stated that:

“Aside from bourgeois parliamentarism, the unions form the principal rampart against the further development of the proletarian revolution in Germany. Their attitude during the world war is well-known […] They have maintained their counter-revolutionary attitude up to today, throughout the whole period of the German revolution.”

Faced with the centrist position of Lenin and the leadership of the CI, the KAPD retorted that:

“The revolutionising of the unions is not a question of individuals: the counter-revolutionary character of these organisations is located in their structure and in their specific way of operating. From this it flows logically that only the destruction of the unions can clear the road for social revolution in Germany.”[10]

Admittedly, these two important questions could not be decided overnight. But the resistance to the rejection of parliamentarism and trade unionism demonstrated the difficulties of the CI in drawing all the implications of the decadence of capitalism for the communist program. The exclusion of the majority of the KPD and the rapprochement of the latter with the Independents (USPD) who controlled the opposition in the official unions was a further sign of the rise of programmatic and organisational opportunism within the world party.

The Second Congress backtracks

At the start of 1920 the CI began to advocate the formation of mass parties: either by the fusion of communist groups with centrist currents, as for example in Germany between the KPD and the USPD; or by the entry of communist groups into parties of the Second International, as for example in Britain where the CI advocated the entry of the Communist Party into the Labour Party. This new orientation completely turned its back on the work of the First Congress that had declared the bankruptcy of social democracy. This opportunist decision was justified by the conviction that the victory of the revolution would result inexorably from the greatest number of organised workers. This position was fought by the Amsterdam Bureau composed by the left of the CI.[11]

The Second Congress, which ran from 19 July to 7 August 1920, foreshadowed a fierce battle between the majority of the CI led by the Bolsheviks, and the left currents, on tactical issues but also on organisational principles. The congress was held during a full “revolutionary war”,[12] in which the Red Army marched on Poland in the belief that it could join with the revolution in Germany. While remaining aware of the danger of opportunism and acknowledging that the party was still threatened by “the danger of dilution by unstable and irresolute elements which have not yet completely discarded the ideology of the Second International”,[13] this Second Congress began to make concessions regarding the analyses of the first congress by accepting the partial integration of certain social democratic parties still strongly marked by the conceptions of the Second International.[14]

To guard against such a danger, the 21 conditions of admission to the CI had been written against the right and centrist elements, but also against the left. During the discussion of the 21 conditions, Bordiga distinguished himself by his determination to defend the communist programme and warned the entire party against any concession in the terms of membership:

“The foundation of the Communist International in Russia led us back to Marxism. The revolutionary movement that was saved from the ruins of the Second International made itself known with its programme, and the work that now began led to the formation of a new state organism on the basis of the official constitution. I believe that we find ourselves in a situation that is not created by accident but much rather determined by the course of history. I believe that we are threatened by the danger of right-wing and centrist elements penetrating into our midst.[15] […] We would therefore be in great danger if we made the mistake of accepting these people in our ranks. […] The right-wing elements accept our Theses, but in an unsatisfactory manner and with certain reservations. We communists must demand that this acceptance is complete and without restrictions for the future. […] I think that, after the Congress, the Executive Committee must be given time to find out whether all the obligations that have been laid upon the parties by the Communist International have been fulfilled. After this time, after the so-called organisation period, the door must he closed […] Opportunism must be fought everywhere. But we will find this task very difficult if, at the very moment that we are taking steps to purge the Communist International, the door is opened to let those who are standing outside come in. I have spoken on behalf of the Italian delegation. We undertake to fight the opportunists in Italy. We do not, however, wish them to go away from us merely to be accepted into the Communist International in some other way. We say to you, after we have worked with you we want to go back to our country and form a united front against all the enemies of the communist revolution.”[16]

Admittedly, the 21 conditions served as a scarecrow against opportunistic elements likely to knock on the door of the party. But even if Lenin could say that the left current was “a thousand times less dangerous and less serious than the error represented by right-wing doctrinarism”, the many regressive steps on the question of tactics strongly weakened the International, especially in the period to come, which was characterised by retreat and isolation contrary to what the CI leadership thought. Inexorably, these safeguards did not allow the IC to resist the pressure of opportunism. In 1921 the Third Congress finally succumbed to the mirage of numbers by adopting Lenin’s “Theses on Tactics”, which advocated work in parliament and the unions as well as the formation of mass parties. With this 180° turn, the party was throwing out of the window the 1918 programme of the KPD, one of the two founding bases of the CI.

The CI - sickness of leftism[17] or opportunism?

It was in opposition to the KPD's opportunist policy that the KAPD was born in April 1920. Although its program was inspired more by the theses of the left in Holland than those of the CI, it requested to be attached immediately to the Third International.

When Jan Appel and Franz Jung[18] arrived in Moscow, Lenin handed them the manuscript of what would become Left-wing Communism, An Infantile Disorder, written for the Second Congress to expose what he saw as the inconsistencies of the left currents.

The Dutch delegation had the opportunity to take note of Lenin's pamphlet during the Second Congress. Herman Gorter was commissioned to write a reply to Lenin, which appeared in July 1920 (Open Letter to Comrade Lenin). Gorter relied heavily on the text published by Pannekoek a few months earlier entitled World Revolution and Communist Tactics. It is not necessary to go back over the details of this polemic here.[19] However, it must be pointed out that the different issues raised echo perfectly the fundamental question: how did the entry into the era of wars and revolutions impose new principles in the revolutionary movement?? Were “compromises” still possible?

For Lenin, left-wing “doctrinairism” was a “childish sickness; “young communists”, still “inexperienced”, had given way to impatience and indulged in “intellectual childishness” instead of defending “the serious tactics of a revolutionary class” according to the “particularity of each country”, taking into account the general movement of the working class.

For Lenin, to reject work in the unions and parliaments, to oppose alliances between the communist parties and the social democratic parties, was a pure nonsense. The adherence of the masses to communism did not depend only on revolutionary propaganda; he considered that these masses had to go through “their own political experience”. For this, it was essential to enrol the greatest numbers in revolutionary organisations, whatever their level of political clarity. The objective conditions were ripe, the path of the revolution was all mapped out...

However, as Gorter pointed out in his reply, the victory of the world revolution depended above all on the subjective conditions, in other words on the ability of the world working class to extend and deepen its class consciousness. The weakness of this general class consciousness was illustrated by the virtual absence of a real vanguard of the proletariat in Western Europe, as Gorter pointed out. Therefore, the error of the Bolsheviks in the CI was “to try to make up for this delay through tactical recipes which expressed an opportunist approach where clarity and an organic process of development were sacrificed in favour of artificial numerical growth at any cost.”[20]

This tactic, based on the quest for instant success, was animated by the observation that the revolution was not developing fast enough, that the class was taking too long to extend its struggle and that, faced with this slowness, it was necessary to make “concessions” by accepting work in trade unions and parliaments.

While the CI saw the revolution as a somehow inevitable phenomenon, the left currents considered that “the revolution in Western Europe [would be] a long drawn out process” (Pannekoek), which would be strewn with setbacks and defeats, to use the words of Rosa Luxemburg. History has confirmed the positions developed by the left currents within the CI. Leftism was therefore not a “childish sickness” of the communist movement but, on the contrary, the treatment against the infection of opportunism that spread in the ranks of the world party.

Conclusion

What lessons can we draw from the creation of the Communist International? If the First Congress had shown the capacity of the revolutionary movement to break with the Second International, the following congresses marked a real setback. Indeed, while the founding congress recognised the passage of social democracy in the camp of the bourgeoisie, the Third Congress rehabilitated it by advocating the tactic of allying with it in a “united front”. This change of course confirmed that the CI was unable to respond to the new questions posed by the period of decadence. The years following its founding were marked by the retreat and defeat of the international revolutionary wave and thus by the growing isolation of the proletariat in Russia. This isolation is the decisive reason for the degeneration of the revolution. Under these conditions, badly armed, the CI was unable to resist the development of opportunism. It too had to empty itself of its revolutionary content and become an organ of the counter-revolution solely defending the interests of the Soviet state.

It was in the very heart of the CI that left fractions appeared to fight against its degeneration. Excluded one after the other during the 1920s, they continued the political struggle to ensure the continuity between the degenerating CI and the party of tomorrow, by learning the lessons from the failure of the revolutionary wave. The positions defended and elaborated by these groups responded to the problems raised in the CI by the period of decadence. In addition to programmatic issues, the lefts agreed that the party must “remain as hard as steel, as clear as glass” (Gorter). This implied a rigorous selection of militants instead of grouping huge masses at the expense of diluting principles. This is exactly what the Bolsheviks had abandoned in 1919 when the Communist International was created. These compromises on the method of building the organisation would also be an active factor in the degeneration of the CI. As Internationalisme pointed out in 1946: “Today we can affirm that just as the absence of communist parties during the first wave of revolution between 1918 and 1920 was one of the causes of its defeat, so the method for the formation of the parties in 1920-21 was one of the main causes for the degeneration of the CPs and the CI”.[21] By favouring quantity at the expense of quality, the Bolsheviks threw into question the struggle they had fought in 1903 at the Second Congress of the RSDLP. For the lefts who were fighting for programmatic and organisational clarity as a prerequisite for CI membership, small numbers were not an eternal virtue but an indispensable step: “If ... we have the duty to confine ourselves for a time with small numbers, it is not because we feel for this situation a particular predilection, but because we have to go through it to become strong” (Gorter).

Alas, the CI had been born in the storms of revolutionary combat. In these conditions, it was impossible to clarify overnight all the questions it had to confront. Tomorrow's party must not fall into the same trap. It must be founded before the revolutionary wave breaks, relying on good programmatic bases but equally on principles of functioning reflected on and clarified beforehand. This was not the case for the CI at the time.

Narek

July 8, 2019.

[1] See our article “Lessons of the revolutionary wave 1917-1923”, International Review n° 80, 1995.

[2] Lenin, closing remarks at the First Congress of the Communist International, in J. Riddell (ed.), Founding the Communist International, Anchor, 1987, p. 257.

[3] “Invitation to the First Congress of the Communist International”, in J. Degras (ed.), The Communist International 1919-1943, Documents, Cass, 1971, p.2.

[4] The Dutch and German Communist Left, ICC, p.136.

[5] The Italian Communist Left, ICC, p.18.

[6] The Dutch and German Communist Left, p.137.

[7] See “Lessons of the revolutionary wave 1917-1923”, International Review n° 80.

[8] Quoted by A. Prudhommeaux, Spartacus Et La Commune De Berlin 1918-1919 [12], Ed. Spartacus, p.55 (in French).

[9] “Letter from the ECCI to the trade unions of all countries”, in Degras, op. cit. p.88.

[10] “1920: the programme of the KAPD”, International Review no 97, 1999 [13].

[11] In autumn 1919 the CI set up a temporary secretariat based in Germany, composed of the right wing of the KPD, and a temporary bureau in Holland that brought together left-wing communists hostile to the KPD's rightward turn.

[12] This “revolutionary war” constituted a catastrophic political decision which the Polish bourgeoisie used to mobilise a part of the Polish working class against the Soviet Republic.

[13] Preamble to the “Conditions of Admission to the CI”. In Degras, Op. Cit., p.168.

[14] This is what Point 14 of the “Basic Tasks of the Communist International” stated: “The degree to which the proletariat in the countries most important from the standpoint of world economy and world politics is prepared for the realisation of its dictatorship is indicated with the greatest objectivity and precision by the breakaway of the most influential parties in the Second International – the French Socialist Party, the Independent Social-Democratic Party of Germany, the Independent Labour Party in England , the American Socialist Party of America – from the yellow International, and by their decision to adhere conditionally to the Communist International. […] The chief thing now is to know how to make this change complete and to consolidate what has been attained in lasting organisational form, so that progress can be made along the whole line without any hesitation.” (in Degras, Op. Cit., p. 124).

[15] Respectively the social patriots and the social democrats: “these supporters of the Second International who think it is possible to achieve the liberation of the proletariat without armed class struggle, without the necessity of introducing the dictatorship of the proletariat after the victory, at the time of the insurrection” (see note 16).)

[16] Speech of Bordiga on the conditions of admission to the CI, Second Congress of the Communist International, Volume One, 1977, pp.221-224.

[17] This term corresponds here to the left communist current which appeared in the CI in opposition to the centrism and opportunism that grew within the party. It has nothing to do with the term for the organisations that belong to the left of capital.

[18] These are the two delegates mandated by the KAPD at the 2nd CI Congress to outline the party's programme.

[19] For more details see The Dutch and German Communist Left, “Chapter 4: The Dutch Left in the Third International".

[20] Ibid.p.150.

[21] Internationalisme, "On the First Congress of the Internationalist Communist Party of Italy", in International Review no 162, 2019.

Rubric:

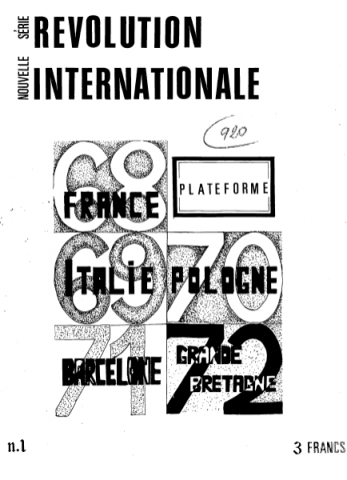

Fifty years ago, May 68: The difficult evolution of the proletarian political milieu (part 1)

- 592 reads

Introduction

The 100th anniversary of the foundation of the Communist International reminds us that the October revolution in Russia had placed the world proletarian revolution on the immediate agenda. The German revolution in particular was already underway and was crucial both to the survival of soviet power in Russia and to the extension of the revolution to the main centres of capitalism. At this moment, all the different groups and tendencies which had remained loyal to revolutionary marxism were convinced that the formation and action of the class party were indispensable to the victory of the revolution. But with hindsight we can say that the late formation of the CI –almost two years after the seizure of power in Russia, and several months after the outbreak of the revolution in Germany- as well as its ambiguities and errors on vital programmatic and organisational questions, was also an element in the defeat of the international revolutionary upsurge.

We need to bear this in mind when we look back at another anniversary: May 68 in France and the ensuing wave of class movements. In the two previous articles in this series, we have looked at the historic significance of these movements, expressions of the reawakening of the class struggle after decades of counter-revolution - the counter-revolution ushered in by the dashing of the revolutionary hopes of 1917-23. We have tried to understand both the origins of the events of May 68 and the course of the class struggle over the next five decades, focusing in particular on the difficulties facing the class in re-appropriating the perspective of the communist revolution.

In this article we want to look specifically at the evolution of the proletarian political milieu since 1968, and to understand why, despite considerable advances at the theoretical and programmatic level since the first revolutionary wave, and despite the fact that the most advanced proletarian groups have understood that it is necessary to take the essential steps towards the formation of a new world party in advance of decisive confrontations with the capitalist system, this horizon still seems to be very far away and sometimes seems to have disappeared from sight altogether.

1968-80: The development of a new revolutionary milieu meets the problems of sectarianism and opportunism

The global revival of the class struggle at the end of the 1960s brought with it a global revival of the proletarian political movement, a blossoming of new groups seeking to re-learn what had been obliterated by the Stalinist counter-revolution, as well as a certain reanimation of the rare organisations which had survived this dark period.

We can get an idea of the components of this milieu if we look at the very diverse list of groups contacted by the comrades of Internationalism in the US with the aim of setting up an International Correspondence Network[1]:

- USA: Internationalism and Philadelphia Solidarity

- Britain: Workers Voice, Solidarity

- France: Révolution Internationale, Groupe de Liaison Pour l’Action des Travailleurs, Le Mouvement Communiste

- Spain: Fomento Obrero Revolucionario

- Italy Partito Comunista Internazionalista (Battaglia Comunista)

- Germany Gruppe Soziale Revolution; Arbeiterpolitik; Revolutionärer Kampf

- Denmark: Proletarisk Socialistisk Arbejdsgruppe, Koministisk Program

- Sweden: Komunismen

- Netherlands: Spartacus; Daad en Gedachte

- Belgium: Lutte de Classe, groupe “Bilan”

- Venzuela; Internacionalismo

In their introduction Internationalism added that a number of other groups had contacted them asking to take part: World Revolution, which had meanwhile split from the Solidarity group in the UK; Pour le Pouvoir Internationale des Conseils Ouvrières and Les Amis de 4 Millions de Jeunes Travailleurs (France); Internationell Arbetarkamp, (Sweden), and Rivoluzione Comunista and Iniziativa Comunista (Italy).

Not all of these currents were a direct product of the open struggles of the late 60s and early 70s: many of them had preceded them, as in the case of Battaglia Comunista in Italy and the Internacialismo group in Venezuela. Some other groups which had developed in advance of the struggles reached their pinnacle in 68 or thereabouts and afterwards declined rapidly – the most obvious example being the Situationists. Nevertheless the emergence of this new milieu of elements searching for communist positions was the expression of a deep process of “underground” growth, of a mounting disaffection with capitalist society which affected both the proletariat (and this also took the form of open struggles like the strike movements in Spain and France prior to 68) and wide layers of a petty bourgeoisie which was itself already in the process of being proletarianised. Indeed the rebellion of the latter strata in particular had already taken on an open form prior to 68 – notably the revolt in the universities and the closely linked protests against war and racism which reached the most spectacular levels in the USA and Germany, and of course in France where the student revolt played an evident role in the outbreak of the explicitly working class movement in May 68. The massive re-emergence of the working class after 68, however, gave a clear answer to those, like Marcuse, who had begun theorising about the integration of the working class into capitalist society and its replacement as a revolutionary vanguard by other layers such as the students. It reaffirmed that the keys to the future of humanity lay in the hands of the exploited class just as it had in 1919, and convinced many young rebels and seekers, whatever their sociological background, that their own political future lay in the workers’ struggle and in the organised political movement of the working class.

The profound connection between the resurgence of the class struggle and this newly politicised layer was a confirmation of the materialist analysis developed in the 30s by the Italian Fraction of the Communist Left. The class party does not exist outside the life of the class. It is certainly a vital, active factor in the development of class consciousness, but it is also a product of that development, and it cannot exist in periods when the class has experienced a world-historic defeat as it had in the 20s and 30s. The comrades of the Italian left had experienced this truth in their own flesh and blood since they had lived through a period which had seen the degeneration of the Communist parties and their recuperation by the bourgeoisie, and the shrinking of genuine communist forces to small, beleaguered groups such as their own. They drew the conclusion that the party could only re-appear when the class as a whole had recovered from its defeat on an international scale and was once again posing the question of revolution: the principal task of the fraction was thus to defend the principles of communism, draw the lessons of past defeats, and to act as a bridge to the new party that would be formed when the course of the class struggle had profoundly altered. And when a number of comrades of the Italian left forgot this essential lesson and rushed back to Italy to form a new party in 1943 when, despite certain important expressions of proletarian revolt against the war, above all in Italy, the counter-revolution still reigned supreme, the comrades of the French communist left took up the torch abandoned by an Italian Fraction which precipitously dissolved itself into the Italian party.

But since, at the end of 60s and the early 70s, the class was finally throwing off the shackles of the counter-revolution, since new proletarian groups were appearing around the world, and since there was a dynamic towards debate, confrontation, and regroupment among these new currents, the perspective of the formation of the party – not in the immediate, to be sure – was once again being posed on a serious basis.

The dynamic towards the unification of proletarian forces took various forms, from the initial travels of Mark Chirik and others from the Internacialismo group in Venezuela to revive discussion with the groups of the Italian left, the conferences organised by the French group Information et Correspondence Ouvrières, or the international correspondence network initiated by Internationalism. The latter was concretised by the Liverpool and London meetings of different groups in the UK (Workers Voice, World Revolution, Revolutionary Perspectives, which had also split from Solidarity and was the precursor of today’s Communist Workers Organisation), along with RI and the GLAT from France.

This process of confrontation and debate was not always smooth by any means: the existence of two groups of the communist left in Britain today – a situation which many searching for class politics find extremely confusing - can be traced to the immature and failed process of regroupment following the conferences in the UK. Some of the divisions that took place at the time had little justification in that they were provoked by secondary differences – for example, the group that formed Pour une Intervention Communiste in France split from RI over exactly when to produce a leaflet about the military coup in Chile. Neverthleless, a real process of decantation and regroupment was taking place. The comrades of RI in France intervened energetically in the ICO conferences to insist on the necessity for a political organisation based on a clear platform in contrast to the workerist, councilist and “anti-Leninist” notions that were extremely influential at the time, and this activity accelerated their unification with groups in Marseille and Clermont Ferrand. The RI group was also extremely active at the international level and its growing convergence with WR, Internationalism, Internacialismo and new groups in Italy and Spain led to the formation of the ICC in 1975, showing the possibility of organising on a centralised international scale. The ICC saw itself, like the GCF in 40s, as one expression of a wider movement and didn’t see its formation as the end-point of the more general process of regroupment. The name “Current” expresses this approach: we were not a fraction of an old organisation, though carrying on much of the work of the old fractions, and were part of a broader stream heading towards the party of the future.

The prospects for the ICC seemed very optimistic: there was a successful unification of three groups in Belgium which drew lessons from the recent failure in the UK, and some ICC sections (especially France and UK) grew considerably in numbers. WR for example quadrupled in numbers from its original nucleus and RI at one point had sufficient members to set up separate local sections in the north and south of Paris. Of course we are still talking about very small numbers but nevertheless this was a significant expression of a real development in class consciousness. Meanwhile the Bordigist International Communist Party established sections in a number of new countries and quickly became the largest organisation of the communist left.

And of particular importance in this process was the development of the international conferences of the communist left, initially called by Battaglia and supported enthusiastically by the ICC even though we were critical of the original basis for the appeal for the conferences (to discuss the phenomenon of “Eurocommunism”, what Battaglia called the “social democratisation” of the Communist parties).

For three years or so, the conferences offered a pole of reference, an organised framework for debate which drew towards it a number of groups from diverse backgrounds[2]. The texts and proceedings of the meetings were published in a series of pamphlets; the criteria for participation in the conferences were more clearly defined than in the original invitation and the subjects under debate became more focused on crucial questions such as the capitalist crisis, the role of revolutionaries, the question of national struggles, and so on. The debates also allowed groups who shared common perspectives to move closer together (as in the case of the CWO and Battaglia and the ICC and För Kommunismen in Sweden).

Despite these positive developments, however, the renascent revolutionary movement was burdened with many weaknesses inherited from the long period of counter-revolution.

For one thing, large numbers of those who could have been won to revolutionary politics were absorbed by the apparatus of leftism, which had also grown considerably in the wake of the class movements after 68. The Maoist and particularly the Trotskyist organizations were already formed and offered an apparently radical alternative to the ‘official’ Stalinist parties whose strike-breaking role in the Events of 68 and afterwards had been plain. Daniel Cohn-Bendit, “Danny the Red”, the feted student leader of 68, had written a book attacking the Communist Party’s function and proposing a “left wing alternative” which referred approvingly to the communist left of the 1920s and to councilist groups like ICO in the present[3]. But like so many others Cohn-Bendit lost patience with remaining in the small world of genuine revolutionaries and went off in search of more immediate solutions that also conveniently offered the possibility of a career, and today is a member of the German Greens who has served his party at the heart of the bourgeois state. His trajectory – from potentially revolutionary ideas to the dead-end of leftism – was followed by many thousands.

But some of biggest problems faced by the emerging milieu were “internal”, even if they ultimately reflected the pressure of bourgeois ideology on the proletarian political vanguard.

The groups which had maintained an organised existence during the period of counter-revolution – largely the groups of the Italian left – had become more or less sclerotic. The Bordigists of the various International Communist Parties[4] in particular had protected themselves against the perpetual rain of new theories that “transcended marxism” by turning marxism itself into an dogma, incapable of responding to new developments, as shown in their reaction to the class movements after 68 - essentially the one which Marx already derided in his letter to Ruge in 1843: here is the truth (the party), down on your knees! Inseparable from the Bordigist notion of the “invariance” of marxism was an extreme sectarianism[5] which rejected any notion of debate with other proletarian groups, an attitude concretised in the flat refusal of any of the Bordigist groups to engage with the international conferences of the communist left. But while the appeal by Battaglia was a small step away from the attitude of seeing your own small group as the sole guardian of revolutionary politics, it was by no means free of sectarianism itself: its invitation initially excluded the Bordigist groups and it was not sent to the ICC as a whole but to its section in France, betraying an unspoken idea that the revolutionary movement is made up of separate “franchises” in different countries (with Battaglia holding the Italian franchise of course).

Moreover sectarianism was not limited to the heirs of the Italian left. The discussions around regroupment in the UK were torpedoed by it. In particular, Workers Voice, frightened of losing its identity as a locally based group in Liverpool, broke off relations with the international tendency around RI and WR around the question of the state in the period of transition, which could only be an open question for revolutionaries who agreed on the essential class parameters of the debate. The same search for an excuse to break off discussions was subsequently adopted by RP and the CWO (product of a short-lived fusion of RP and WV) who declared the ICC to be counter-revolutionary because it did not accept that the Bolshevik party and the CI had lost all proletarian life from 1921 and not a moment later. The ICC was better armed against sectarianism because it traced its origins in the Italian Fraction and the GCF, who had always seen themselves as part of a wider proletarian political movement and not as the sole repository of truth. But the calling of the conferences had also exposed elements of sectarianism in its own ranks; some comrades initially responded to the appeal by declaring that the Bordigists and even Battaglia were not proletarian groups because of their ambiguities on the national question. Significantly, the subsequent debate about proletarian groups which led to a great deal of clarification in the ICC[6] was launched by a text by Marc Chirik who had been “trained” in the Italian and French left to understand that proletarian class consciousness is by no means homogeneous, even among the more politically advanced minorities, and that you could not determine the class nature of an organisation in isolation from its history and its response to major historical events, in particular world war and revolution.

With the new groups, these sect-like attitudes were less the product of a long process of sclerosis than of immaturity and the break in continuity with the traditions and organisations of the past. These groups were faced with the need to define themselves against the prevailing atmosphere of leftism, so that a kind of rigidity of thought often appeared to be a means of defence against the danger of being sucked under by the much larger organisations of the bourgeois left. And yet, at the same time, the rejection of Stalinism and Trotskyism often took the form of a flight into anarchist and councilist attitudes – manifested not only the tendency to reject the whole Bolshevik experience but also in a widespread suspicion of any talk about forming a proletarian party. More concretely, such approaches favoured federalist conceptions of organising, the equation of centralized forms of organization with bureaucracy and even Stalinism. The fact that many adherents of the new groups had come out of a student movement much more marked by the petty bourgeoisie than the student milieu of today reinforced these democratist and individualist ideas, most clearly expressed in the neo-Situationist slogan “militantism: the highest stage of alienation”[7]. The result of all this is that the revolutionary movement has spent decades struggling to understand the organisation question, and this lack of understanding has been at the heart of many conflicts and splits in the movement. Of course, the organisation question has of necessity been a constant battleground within the workers’ movement (witness the split between Marxists and Bakuninists in the First International, or between the Bolsheviks and the Mensheviks in Russia). But the problem in the re-emerging revolutionary movement at the end of the 60s was exacerbated by the long break in continuity with the organisations of the past, so that many of the lessons bequeathed by previous organisational struggles had to be re-learned almost from scratch.

It was essentially the inability of the milieu as a whole to overcome sectarianism that led to the blockage and eventual sabotage of the conferences[8]. From the beginning, the ICC had insisted that the conferences should not remain dumb but should, where possible, issue a minimum of joint statements, to make clear to the rest of the movement what points of agreement and disagreement had been reached, but also – faced with major international events like the class movement in Poland or the Russian invasion of Afghanistan – to make a common public statements around questions which were already essential criteria for the conferences, such as opposition to imperialist war. These proposals, supported by some, were rejected by Battaglia and the CWO on the grounds that it was “opportunist” to make joint statements when other differences remained. Similarly, when Munis and the FOR walked out of the second conference because they refused to discuss the question of the capitalist crisis, and in response to the ICC’s proposal to issue a joint criticism of the FOR’s sectarianism, BC simply rejected the idea that sectarianism was a problem: the FOR had left because it had different positions, so what’s the problem?

Clearly, underneath these divisions there were quite profound disagreements about what a proletarian culture of debate should be like, and matters reached a head when BC and the CWO suddenly introduced a new criterion for participation in the conferences – a formulation about the role of the party which contained ambiguities about its relationship to political power which they knew would not be acceptable to the ICC and which effectively excluded it. This exclusion was itself a concentrated expression of sectarianism, but it also showed that the other side of the coin of sectarianism is opportunism: on the one hand, because the new “hard” definition of the party did not prevent BC and the CWO holding a farcical 4th conference attended only by themselves and the Iranian leftists of the Unity of Communist Militants[9]; and on the other hand because, with the rapprochement between BC and the CWO, BC probably calculated that it had gained all it could from the conferences, a classic case of sacrificing the future of the movement for immediate gain. And the consequences of the break-up of the conferences have indeed been heavy – the loss of any organised framework for debate, for mutual solidarity, and an eventual common practice between the organisations of the communist left, which has never been restored despite occasional efforts towards joint work in subsequent years

The 1980s: crises in the milieu

The collapse of the conferences was soon revealed to be one aspect of a wider crisis in the proletarian milieu, expressed most clearly by the implosion of the Bordigist ICP and the “Chenier affair” in the ICC, which led to a number of members leaving the organisation, particularly in the UK.