International Review 162 - Spring-Summer 2019

- 239 reads

Presenting the Review 162

- 66 reads

Like the last two issues of the Review, this one continues the celebration of centenaries of the historic events of the world-wide revolutionary wave of 1917-23.

Thus, after the revolution in Russia in 1917 (International Review nº 160), the revolutionary attempts in Germany in 1918-19 (International Review nº 161), this issue celebrates the foundation of the Communist International. All these experiences are essential parts of the political heritage of the world proletariat, which the bourgeoisie does everything it can to disfigure (as in the case of the revolutions in Russia or Germany) or simply to consign them to oblivion, as is the case with the foundation of the Communist International. The proletariat has to re-appropriate these experiences so that the next attempt at world revolution will be victorious.

This relates in particular to the following questions, some of which are dealt with in this Review:

- The world-wide revolutionary wave of 1917-23 was the response of the international working class to the First World War, to four years of butchery and military confrontations between capitalist states with the aim of re-dividing the world.

- The foundation of the Communist International (CI) in 1919 was the culminating point of this first revolutionary wave.

- The foundation of the CI made concrete, first and foremost, the necessity for revolutionaries who remained loyal to the principle of internationalism, which had been betrayed by the right wing of the Social Democratic parties (the majority in most of these parties), to work for the construction of a new International. At the forefront of this effort, this perspective, were the left currents in the Social Democratic parties, grouped around Rosa Luxemburg in Germany, Pannekoek and Gorter in Holland, and of course the Bolshevik fraction of the Russian party around Lenin. It was on the initiative of the Communist Party of Russia (Bolshevik) and the Communist Party of Germany (the KPD, formerly the Spartacus League) that the First Congress of the International was called in Moscow on 2 March 1919.

- The foundation of the new party, the world party of the revolution, was already late in that the majority of revolutionary uprisings by the proletariat in Europe had been violently suppressed. The mission of the CI was to provide a clear political orientation to the working class: the overthrow of the bourgeoisie, the destruction of its state and the construction of a new world without war or exploitation.

- The platform of the CI reflected the profound change in historical period opened by the First World War: “A new epoch is born! The epoch of the dissolution of capitalism, of its inner disintegration. The epoch of the communist revolution of the proletariat" (Platform of the CI). The only alternative for society was now world proletarian revolution or the destruction of humanity; socialism or barbarism.

All these aspects of the foundation of the CI are developed in two articles in the present Review, the first in particular: “1919: the International of Revolutionary Action”. The second article, “Centenary of the foundation of the Communist International: what lessons can we draw for future combats?”, develops an idea already raised in the first article: because of the urgency of the situation, the main parties that founded the International, notably the Bolshevik party and the KPD, were not able to clarify their divergences and confusions in advance.

Moreover, the method employed in the foundation of the new party would not arm it for the future. A large part of the revolutionary vanguard put quantity, in terms of the number adhering to the new parties, above a prior clarification of programmatic and organisational principles. Such an approach turned its back on the very conceptions elaborated and developed by the Bolsheviks during their existence as a fraction within the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party.

This lack of clarification was an important factor, in the context of the reflux of the revolutionary wave, in the development of opportunism in the International. This was to be at the root of a process of degeneration which led to the eventual bankruptcy of the CI, just as had been the case with the IInd International. This new International was also to succumb through the abandonment of internationalism by the right wing of the Communist Parties. Following that, in the 1930s, in the name of defending the “Socialist Fatherland”, the Communist Parties in all countries trampled on the flag of the International by calling on workers to slaughter each other once again, on the battlefields of the Second World War.

Against this process of degeneration, the CI, like the IInd International, gave rise to left wing minorities which remained loyal to internationalism and to the slogan “The workers have no country, workers of the world unite!”. One of these fractions, the Italian Fraction of the Communist left, and then the French Fraction which subsequently became the Gauche Communiste de France (GCF) carried out a whole balance sheet of the revolutionary wave. We are publishing two chapters from nº 7 (January-February 1946) of the review Internationalisme, dealing with the question of the role of the fractions which come out of a degenerating party (“The Left Fraction”) and their contribution to the formation of the future party, in particular the method that has to be applied to this task (“Method for forming the party”).

These revolutionary minorities, more and more reduced in size, had to work in the context of a deepening counter-revolution, illustrated in particular by the absence of revolutionary uprisings at the end of the Second World War – in contrast to what happened at the end of the previous war. Thus this new world conflict was a moment of truth for the weak forces which remained on a class terrain after the CPs had betrayed the case of the proletarian International. The Trotskyist current in turn betrayed, although its passage into the enemy camp engendered proletarian reactions from within it.

Internationalisme nº 43 (June-July 1949) contained an article “Welcome to Socialisme ou Barbarie” (republished in International Review nº 161 as part of the article “Castoriadis, Munis and the problem of breaking with Trotskyism”). The article by Internationalisme took a clear position on the nature of the Trotskyist movement, which had abandoned proletarian positions by participating in the Second World War. The article is a good example of the method used by the GCF in its relations with those who had escaped the shipwreck of Trotskyism in the wake of the war. In the second part of “Castoriadis, Munis and the problem of breaking with Trotskyism”, published in this issue of the Review, it is shown how difficult it was, for those who had grown up in the corrupted milieu of Trotskyism, to make a profound break with its basic ideas and attitudes. This reality is illustrated by the trajectory of two militants, Castoriadis and Munis, who, without doubt, at the end of the 40s and beginning of the 50s, were militants of the working class. Munis remained as such for his whole life, but this wasn’t the case with Castoriadis who deserted the workers’ movement.

With regard to Munis, our article demonstrates his difficulty in breaking with Trotskyism: “Underlying this refusal to analyse the economic dimension of capitalism’s decadence there lies an unresolved voluntarism, the theoretical foundations of which can be traced back to the letter announcing his break from the Trotskyist organisation in France, the Parti Communiste Internationaliste, where he steadfastly maintains Trotsky’s notion, presented in the opening lines of the Transitional Programme, that the crisis of humanity is the crisis of revolutionary leadership.”

On Castoriadis, it is underlined that “In reality, this ‘radicalism’ that makes highbrow journalists drool so much was a fig leaf covering the fact that Castoriadis' message was extremely useful to the ideological campaigns of the bourgeoisie. Thus, his declaration that marxism had been pulverised (The rise of Insignificance, 1996) gave its ‘radical’ backing to the whole campaign about the death of communism which developed after the collapse of the Stalinist regimes of the eastern bloc in 1989”. He was, in a sense, one of the founding fathers of what we have called the “modernist” current

Also in this issue of the Review we continue the denunciation, begun in nº 160, of the union of all the national sectors and parties of the world bourgeoisie against the Russian revolution, to block the revolutionary wave and prevent its spread to the main industrial countries of Western Europe. Faced with the revolutionary attempts in Germany, the SPD played a key role in butchering these uprisings, and the campaigns of slander it used to justify this bloody repression, organised from the very summit of the state, were truly disgusting. Later on, Stalinism also took up its post as the butcher of the revolution, through the imposition of state terror and the liquidation of the Bolshevik Old Guard. From the moment that the USSR became a bourgeois imperialist state, the great democracies became its accomplice in the physical and ideological liquidation of October 1917. This ideological and political alliance was to last for many years and was to be re-launched, stronger than ever, when the collapse of the Eastern bloc and of Stalinism, a particular form of state capitalism, was falsely presented as the failure of communism.

This Review doesn’t contain an article on the burning questions of the current world situation. However our readers can find such articles on our website and the next issue of the Review will accord the necessary importance to these questions

14.5.19

1919: The International of Revolutionary Action

- 425 reads

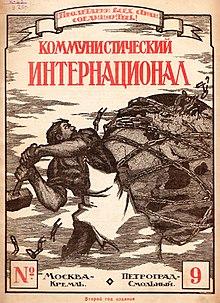

100 years ago, in March 1919, the first congress of the Communist International (CI) was held: the founding congress of the Third International.

If revolutionary organisations did not have the will to celebrate this event, the foundation of the International would be relegated to the oblivion of history. Indeed, the bourgeoisie is interested in keeping silent about this event, while it continues to shower us with celebrations of all kinds such as the centenary of the end of the First World War. The ruling class does not want the working class to remember its first great international revolutionary experience of 1917-1923. The bourgeoisie would like to be able to finally bury the spectre of the revolutionary wave which gave birth to the CI. This revolutionary wave was the international proletariat's response to the First World War, four years of slaughter and military clashes between the capitalist states to carve up the world.

The revolutionary wave began with the victory of the Russian revolution in October 1917. It manifested itself in the mutinies of soldiers in the trenches and the proletarian uprising in Germany in 1918.

The wave spread throughout Europe, it even reached the countries of the Asian continent (especially China in 1927). The countries of the Americas, such as Canada and the United States to Latin America, were also shaken by this global revolutionary upheaval.

We must not forget that it was fear of the international expansion of the Russian revolution that forced the bourgeoisie of the great European powers to sign the armistice to end the First World War.

In this context, the founding of the Communist International in 1919 represented the culmination of this first revolutionary wave.

The Communist International was founded to give a clear political orientation to the working masses. Its objective was to show the proletariat the way to overthrow the bourgeois state and build a new world without war and exploitation. We can recall here what the Statutes of the CI affirmed (adopted at its Second Congress in July 1920):

"The Communist International was formed after the conclusion of the imperialist war of 1914-18, in which the imperialist bourgeoisie of the different countries sacrificed 20 million men.

'Remember the imperialist war!' These are the first words addressed by the Communist International to every working man and woman; wherever they live and whatever language they speak. Remember that because of the existence of capitalist society a handful of imperialists were able to force the workers of the different countries for four long years to cut each other's throats. Remember that the war of the bourgeoisie conjured up in Europe and throughout the world the most frightful famine and the most appalling misery. Remember, that without the overthrow of capitalism the repetition of such robber wars is not only possible, but inevitable."

The foundation of the CI expressed first and foremost the need for revolutionaries to come together to defend the principle of proletarian internationalism. A basic principle of the workers' movement that the revolutionaries had to preserve and defend against wind and tide!

To understand the importance of the foundation of the CI, we must first recall that the Third International was in historical continuity with the First International (the IWMA) and the Second International (the International of social democratic parties). This is why the Manifesto of the CI stated:

“In rejecting the timidity, the lies, and the corruption of the obsolete official socialist parties, we communists, united in the Third International, consider that we are carrying on in direct succession the heroic endeavours and martyrdom of a long line of revolutionary generations from Babeuf to Karl Liebknecht and Rosa Luxemburg. If the First International predicted the future course of development and indicated the roads it would take, if the Second International rallied and organised millions of proletarians, then the Third International is the International of open mass struggle, the International of revolutionary realisation, the International of action.”

It is therefore clear that the CI did not come from nowhere. Its principles and revolutionary programme were the emanation of the whole history of the workers' movement, especially since the Communist League and the publication of the Manifesto written by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels in 1848. It was in the Communist Manifesto they put forward the famous slogan of the workers’ movement: "The proletarians have no country. Proletarians of all countries, unite!"

To understand the historical significance of the founding of the CI, we must remember that the Second International died in 1914. Why? Because the main parties of this Second International, the Socialist parties, had betrayed proletarian internationalism. The leaders of these treacherous parties voted for war credits in parliament. In each country, they called the proletarians to join the "Union Sacrée" with their own exploiters. They called on them to kill each other in the world butchery in the name of defending the homeland, when the Communist Manifesto affirmed that "the proletarians have no country"!

Faced with the shameful collapse of the Second International, only a few social democratic parties were able to weather the storm, including the Italian, Serbian, Bulgarian and Russian parties. In other countries, only a small minority of militants, often isolated, remained faithful to proletarian internationalism. They denounced the bloody orgy of war and tried to regroup. In Europe, it was this minority of internationalist revolutionaries who would represent the left, especially around Rosa Luxemburg in Germany, Pannekoek and Gorter in Holland and of course the Bolshevik fraction of the Russian party around Lenin.

From the death of the Second International in 1914 to the founding of the CI in 1919

Two years before the war, in 1912 the Basle congress of the Second International was held. With the threat of a world war in the heart of Europe looming, this congress adopted a resolution on the issue of war and proletarian revolution. This affirmed:

“Let the governments remember that with the present condition of Europe and the mood of the working class, they cannot unleash a war without danger to themselves. Let them remember that the Franco-German War was followed by the revolutionary outbreak of the Commune, that the Russo-Japanese War set into motion the revolutionary energies of the peoples of the Russian Empire (…) The proletarians consider it a crime to fire at each other for the profits of the capitalists, the ambitions of dynasties, or the greater glory of secret diplomatic treaties.”

It was also in the Second International that the most consistent marxist theorists, particularly Rosa Luxemburg and Lenin, were able to analyse the change in the historic period in the life of capitalism. Luxemburg and Lenin had in fact clearly demonstrated that the capitalist mode of production had reached its peak in the early twentieth century.. They understood that the imperialist war in Europe could now have only one goal: the division of the world between the main rival powers in the race for colonies. Lenin and Rosa Luxemburg understood that the outbreak of the First World War marked the entry of capitalism into its period of decadence and historical decline. But already, well before the outbreak of war, the left wing of the Second International had to fight hard against the right, against the reformists, centrists and opportunists. These future renegades theorised that capitalism still had good days ahead of it and that, ultimately, the proletariat did not need to make the revolution or overthrow the power of the bourgeoisie.

The fight of the left for the construction of a new International

In September 1915, at the initiative of the Bolsheviks, the Zimmerwald International Socialist Conference was held in Switzerland. It was followed by a second conference in April 1916 in Kienthal, Switzerland. Despite the very difficult conditions of war and repression, delegates from eleven countries participated (Germany, Italy, Russia, France, etc.). But the majority of the delegates were pacifists and refused to break with the social chauvinists who had passed into the bourgeoisie's camp by voting for war credits in 1914.

So there was also at the Zimmerwald Conference a left wing united behind the delegates of the Bolshevik fraction, Lenin and Zinoviev. This "Zimmerwald left" defended the need to break with the social democratic party traitors. This left highlighted the need to build a new International. Against the pacifists, it argued, in Lenin's words, that "the struggle for peace without revolutionary action is a hollow and untrue phrase". The left of Zimmerwald had taken up Lenin's slogan: "Turn the imperialist war into a civil war!" A watchword that was already contained in the resolutions of the Second International passed at the Stuttgart Congress in 1907 and especially the Basle Congress in 1912.

The Zimmerwald left would therefore constitute the "first nucleus of the Third International in formation" (as Lenin's companion, Zinoviev, would say in March 1918). The new parties that were created, breaking with social democracy, then began to take the name of "communist party". It was the revolutionary wave opened up by the Russian revolution of October 1917 that gave a vigorous impetus to the revolutionary militants for the founding of the CI. The revolutionaries had indeed understood that it was absolutely vital to found a world party of the proletariat for the victory of the revolution on a world scale.

It was at the initiative of the Communist Party (Bolshevik) of Russia and the Communist Party of Germany (KPD, formerly the Spartacus League) that the first congress of the International was convened in Moscow on 2 March 1919.

The political programme of the Communist International

The platform of the CI was based on the programme of the two main communist parties, the Bolshevik Party and the Communist Party of Germany (founded on 29 December 1918).

This CI platform began by stating clearly that “A new epoch is born! The epoch of the dissolution of capitalism, of its inner disintegration. The epoch of the communist revolution of the proletariat". By taking up the speech on the founding programme of the German Communist Party by Rosa Luxemburg, the International made it clear that " the dilemma faced by humanity today is as follows: fall into barbarism, or salvation through socialism.” In other words, we had entered the "era of wars and revolutions". The only alternative for society was now: world proletarian revolution or destruction of humanity; socialism or barbarism. This position was strongly affirmed in the first point of the Letter of Invitation to the founding congress of the Communist International (written in January 1919 by Trotsky).

For the International, the entry of capitalism into its period of decadence meant that the revolutionary struggle of the proletariat took on a new form. This was the period in which the mass strike was developing, the period when the workers' councils were the form of the dictatorship of the proletariat, as announced by the appearance of the soviets in Russia in 1905 and 1917.

But one of the fundamental contributions of the International was the understanding that the proletariat must destroy the bourgeois state in order to build a new society. It is from this question that the First Congress of the International adopted its Theses on bourgeois democracy and proletarian dictatorship (drafted by Lenin). These theses began by denouncing the false opposition between democracy and dictatorship "because, in no civilized capitalist country, is there "democracy in general", but only a bourgeois democracy". The International thus affirmed that to defend "pure" democracy in capitalism was, in fact, to defend bourgeois democracy, the form par excellence of the dictatorship of capital. Against the dictatorship of capital, the International affirmed that only the dictatorship of the proletariat on a world scale could overthrow capitalism, abolish social classes, and offer a future to humanity.

The world party of the proletariat therefore had to give a clear orientation to the proletarian masses to enable them to achieve their ultimate goal. It had to defend everywhere the slogan of the Bolsheviks in 1917: "All power to the soviets". This was the "dictatorship" of the proletariat: the power of the soviets or workers' councils.

From the difficulties of the Third International to its bankruptcy

In March 1919, the International was unfortunately founded too late, at a time when most of the revolutionary uprisings of the proletariat in Europe had been violently repressed. In fact the CI was founded two months after the bloody repression of the German proletariat in Berlin. The Communist Party of Germany had just lost its principal leaders, Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Liebknecht, savagely murdered by the social democratic government during the bloody week in Berlin in January 1919. So at the moment when it was constituted the International had suffered its first defeat. With the crushing of the revolution in Germany, this defeat was also and above all a terrible defeat for the international proletariat.

It must be recognised that revolutionaries at the time were facing a terribly urgent situation when they founded the International. The Russian revolution was completely isolated, suffocated and encircled by the bourgeoisie of all countries (not to mention the counter-revolutionary exactions of the White Armies inside Russia). The revolutionaries were caught by the throat and it was necessary to act quickly to build the world party. It is because of this urgency that the main founding parties of the International, including the Bolshevik Party and the KPD, had not been able to clarify their differences and confusions. This lack of clarification was an important factor in the development of opportunism in the International with the reflux of the revolutionary wave.

Subsequently, because of the gangrene of opportunism, this new International died in its turn. It also succumbed to the betrayal of the principle of internationalism by the right wing of the Communist parties. In particular, the main party of the International, the Bolshevik Party, after the death of Lenin had begun to defend the theory of "building socialism in one country". Stalin, taking the head of the Bolshevik Party, was the mastermind of the repression of the proletariat which had made the revolution in Russia, imposing a ferocious dictatorship against Lenin's old comrades who fought against the degeneration of the International and denounced what they saw as the return of capitalism to Russia.

Subsequently, in the 1930s, it was in the name of defending the "Soviet Fatherland" that the Communist parties in all countries trampled the flag of the International in calling on proletarians, again, to kill each other on the battlefields of the Second World War. Just like the Second International in 1914, the CI had become bankrupt. Just like the International in 1914, the CI was also a victim of the gangrene of opportunism and a process of degeneration. But like the Second International, the CI also secreted a left minority, militants who remained loyal to internationalism and the slogan “The proletarians have no country. Proletarians of all countries unite!” These left-wing minorities (in Germany, France, Italy, Holland ...) waged a political fight within the degenerating International to try to save it. But Stalin eventually excluded these militants from the International. He hunted them, persecuted them and liquidated them physically (we recall the Moscow trials, the assassination of Trotsky by GPU agents and also the Stalinist Gulags).

The revolutionaries excluded from the Third International also sought to regroup, despite all the difficulties of war and repression. Despite their scattering in different countries, these tiny minorities of internationalist militants were able to make a balance sheet (bilan) of the revolutionary wave of 1917-1923 in order to identify the main lessons for the future.

The revolutionaries who fought Stalinism did not seek to found a new International, before, during or after the Second World War. They understood that it was "midnight in the century": the proletariat had been physically crushed, massively mobilised behind the national flags of anti-fascism and the victim of the deepest counter-revolution in history. The historic situation was no longer favourable to the emergence of a new revolutionary wave against the World War.

Nevertheless, throughout this long period of counter-revolution, the revolutionary minorities continued to carry out an activity, often in hiding, to prepare for the future by maintaining confidence in the capacity of the proletariat to raise its head and one day overthrow capitalism. .

We want to recall that the ICC reclaims the contribution of the Communist International. Our organisation also considers itself in political continuity with the left fractions excluded from the International in the 1920s and 30s, especially the Italian Fraction of the Communist Left. This centenary is therefore both an opportunity to salute the invaluable contribution of the CI in the history of the workers' movement, but also to learn from this experience in order to arm the proletariat for its future revolutionary struggles.

Once again, we must fully understand the importance of the founding of the Communist International as the first attempt to constitute the world party of the proletariat. Above all, we must emphasise the importance of the historical continuity, of the common thread which connects the revolutionaries of today and those of the past, of all those militants who, because of their fidelity to the principles of the proletariat, were persecuted and savagely murdered by the bourgeoisie, and especially by their old comrades who became traitors: Noske, Ebert, Scheidemann, Stalin. We must also pay tribute to all those exemplary militants (Rosa Luxemburg, Karl Liebknecht, Leo Jogiches , Trotsky and many others) who paid with their lives for their loyalty to internationalism.

To be able to build the future world party of the proletariat, without which the overthrow of capitalism will be impossible, revolutionary minorities must regroup, today as in the past. They must clarify their differences through the confrontation of positions, collective reflection and the widest possible discussion. They must be able to learn from the past in order to understand the present historical situation and to allow new generations to open the doors of the future.

Faced with the decomposition of capitalist society, the barbarism of war, the exploitation and growing misery of proletarians, today the alternative remains the one that the Communist International clearly identified 100 years ago: socialism or barbarism, world proletarian revolution or destruction of humanity in an increasingly bloody chaos.

ICC

Rubric:

Centenary of the foundation of the Communist International - What lessons can we draw for future combats?

- 309 reads

A century ago a wind of hope blew for humanity: in Russia first of all the working class had just taken power. In Germany, Hungary and then in Italy it fought courageously to follow the Russian example with a single agenda: the abolition of the capitalist mode of production whose contradictions had plunged civilisation into four years of war. Four years of unprecedented barbarity that confirmed the entry of capitalism into its phase of decadence.

In these conditions, acknowledging the bankruptcy of the Second International and basing itself on all the work of the reconstruction of international unity started at Zimmerwald in September 1915, then Kienthal in 1916, the Third, Communist International (CI) was founded on March 4 1919 in Moscow. In his April Thesis of 1917, Lenin had already called for the foundation of a new world party. For Lenin a decisive step was taken during the terrible days of January 1919 in Germany, during the course of which the German Communist Party (KPD) was founded. In a "Letter to the workers of Europe and America" dated January 26, Lenin wrote: "When the Spartacus League became the German Communist Party, then the founding of the 3rd International became a fact. Formally this foundation hadn't yet been decided upon, but in reality the 3rd International exists from now". Leaving aside the excessive enthusiasm of such a judgment, as we will see later, revolutionaries at the time understood that it was now indispensable to forge the party for the victory of the revolution at the world level. After several weeks of preparation, 51 delegates met up from March 2 to March 6 1919, in order to lay out the organisational and programmatic markers which would allow the world proletariat to continue to advance the struggle against all the forces of the bourgeoisie.

The ICC lays claim to the contributions of the Communist International. This centenary is thus an occasion to salute and underline the inestimable work of the CI in the history of the revolutionary movement, but equally to draw the lessons of this experience and draw out its weaknesses in order to arm the proletariat of today for its future battles.

Defending the struggle of the working class in the heat of revolution

As Trotsky's "Letter of invitation to the congress" confirmed: "The undersigned parties and organisations consider that the convening of the first congress of the new revolutionary International is urgently necessary (...) The very rapid rise of the world revolution, which constantly poses new problems, the danger of strangulation of this revolution under the hypocritical banner of the ‘League of Nations’, the attempts of the social-traitor parties to join together and further help their governments and their bourgeoisies in order to betray the working class after granting each other a mutual ‘amnesty’, and finally, the extremely rich revolutionary experience already acquired and the world-wide character of the whole revolutionary movement – all these circumstances compel us to place on the agenda of the discussion the question of the convening of an international congress of proletarian-revolutionary parties".

In the image of the first appeal launched by the Bolsheviks, the foundation of the CI expressed the will for the regroupment of revolutionary forces throughout the world. But it equally expressed the defence of proletarian internationalism which had been trampled underfoot by the great majority of the social democratic parties who made up the 2nd International. After four years of atrocious war which had divided and decimated millions of proletarians on the field of battle, the emergence of a new world party was witness to the will to deepen the work begun by the organisations who remained faithful to internationalism. In this the CI was the expression of the political strength of the proletariat, which again manifested itself after the profound defeat caused by the war, and also of the responsibility of revolutionaries to continue to defend the interests of the working class and the world revolution.

During the course of the congress it was said many times that the CI was the party of revolutionary action. As it affirms in its Manifesto, the CI saw the light of day at the moment that capitalism had clearly demonstrated its obsolescence. From here on humanity entered "the era of wars and revolutions". In other words, the abolition of capitalism became an extreme necessity for the future of civilisation. It was with this new understanding of the historic evolution of capitalism that the CI tirelessly defended the workers' councils and the dictatorship of the proletariat: "The new apparatus of power must represent the dictatorship of the working class (...) it must, that is to say, be the instrument for the systematic overthrow of the exploiting class and its expropriation (...) The power of the workers' councils or the workers' organisations is its concrete form" (Letter of invitation to the congress). These orientations were defended throughout the congress. Moreover, the "Theses on Bourgeois Democracy", written by Lenin and adopted by the congress, focussed on denouncing the mystification of democracy, on warning the proletariat about the danger that it posed in its struggle against bourgeois society. From the outset the CI placed itself resolutely in the proletarian camp by defending the principles and methods of working class struggle, while energetically denouncing the call from the centrist current for an impossible unity between the social-aitors and the communists: "the unity of communist workers with the assassins of the leading communists Liebknecht and Luxemburg", according the terms of the "Resolution of the first congress of the CI on the position towards the socialist currents and the Berne Conference". This resolution was evidence of the intransigent defence of proletarian principles and was voted on unanimously by the congress. It was adopted in reaction to the recent meeting held by the majority of the social democratic parties of the 2nd International [1] which had taken up a certain number of orientations openly aimed against the revolutionary wave. The resolution ended with these words: "The congress invites the workers of every country to begin the most energetic struggle against the yellow international and to warn the widest numbers of the proletariat about this International of lies and betrayal".

The foundation of the CI turned out to be a vital stage for advancing the historical struggle of the proletariat. It took up the best contributions of the 2nd International while discarding those positions and analyses which no longer corresponded to the historic period which had just opened up[2]. Whereas the former world party had betrayed proletarian internationalism in the name of the Sacred Union on the eve of the First World War, the foundation of the new party strengthened the unity of the working class, arming it for the bitter struggle that it had to undertake across the planet for the abolition of the capitalist mode of production. Thus, despite the unfavourable circumstances and the errors committed - as we will see - we salute and support such an enterprise. Revolutionaries of that time took up their responsibilities; it had to be done and they did it!

A foundation in unfavourable circumstances

Revolutionaries faced with a massive surge from the world proletariat

The year 1919 was the culminating point of the revolutionary wave. After the victory of the revolution in Russia in October 1917, the abdication of Wilhelm II and the precipitous signing of the armistice faced with mutinies and revolts of masses of workers in Germany, workers' insurrections broke out in numerous places, most notably with the setting up of republics of councils in Bavaria and Hungary. There were also mutinies in the fleets and among French troops, as well as in British military units, refusing to intervene against soviet Russia. In 1919 a wave of strikes hit Britain (Sheffield, the Clyde, South Wales and Kent). But in March 1919, at the moment the CI appeared in Moscow, the great majority of uprisings had been suppressed or were on course to be.

There is no doubt that revolutionaries of that time found themselves in a situation of urgency and they were obliged to act in the fire of revolutionary battle. As the French Fraction of the Communist Left (FFCL) underlined in 1948: "revolutionaries tried to fill the gap between the maturity of the objective situation and the immaturity of the subjective factor (the absence of the party) by a gathering in numbers of politically heterogeneous groups and currents and called this coming together the new Party".[3]

It's not a question here of discussing the validity or not of the foundation of the new party, of the International. It was an absolute necessity. On the other hand we want to point to a certain number of errors in the way in which it was realised.

An overestimation of the situation in which the party was founded

Even though the majority of reports submitted by the different delegates on the situation of the class struggle in each country took into account the reaction of the bourgeoisie faced with the advance of the revolution (a resolution the White Terror was voted on at the end of the congress), it's striking to see to what point this aspect was largely underestimated during these five days of work. Already, some days after the news of the foundation of the KPD, which followed the founding of the communist parties of Austria (November 1918) and Poland (December 1918), Lenin considered that the die was already cast: "When the German Spartacus League, led by its illustrious leaders known the world over, these loyal partisans of the class struggle such as Liebknecht, Rosa Luxemburg, Clara Zetkin, Franz Mehring, definitively broke all links with socialists such as Scheidemann (...) when the Spartacus League became the German Communist Party, then the foundation of the 3rd International, the Communist International, truly proletarian, truly international, truly revolutionary, became a fact. This foundation wasn't formally sanctified, but, in reality, the 3rd International now exists" [4]. To add a significant anecdote here: this text was finished and drafted on January 21 1919, the date on which Lenin was told about the assassination of Karl Liebknecht. And yet an unwavering certainty ran through the congress and Lenin announced it with: "The bourgeoisie can unleash its terror, it may assassinate millions of workers, but victory is ours, the victory of the world communist revolution is assured". Consequently all the reporters of the situation overflowed with the same optimism; like comrade Albert, a young member of the KPD who on March 2 expressed himself to the congress in these words: "I'm not expressing an exaggerated optimism by affirming that the German and Russian communist parties continue the struggle, firmly hoping that the German proletariat will also lead the revolution to the final victory and the dictatorship of the proletariat will equally be established in Germany, despite all the national assemblies, despite all the Scheidemanns and despite the national bourgeoisie (...) It is this which motivated me to accept your invitation with joy, convinced that after a short delay we will struggle side by side with the proletariat of other countries, particularly France and Britain, for the world revolution in order to realise the objectives of the revolution in Germany". A few days later, between March 6 and 9, a terrible repression struck Berlin, killing 3000 workers including 28 sailors imprisoned and then executed by firing squad in the tradition of Versailles! On March 10, Leo Jogisches was assassinated and Heinrich Dorrenbach[5] met the same fate on May 19.

However, the last words of Lenin of the closing speech of the congress showed that it hadn't moved one iota on the relationship of force between the two classes. Without hesitation it affirmed: "The victory of the proletarian revolution is assured throughout the entire world. The foundation of the International Republic of Councils is underway."

But as Amedeo Bordiga noted a year later: "After the slogan ‘Soviet regimes’ was launched onto the world by the Russian and international proletariat we first of all saw the revolutionary wave resurface after the end of the war and the proletariat of the entire world move into action. In every country we saw the old socialist parties filtered out and the communist parties were born, engaging in the revolutionary struggle against the bourgeoisie. Unfortunately the period which followed has been a period of check because the German, Bavarian and Hungarian revolutions have all been wiped out by the bourgeoisie."

In fact, important weaknesses of consciousness in the working class constituted a major hindrance to a revolutionary development:

* the difficulties of these movements to overcome the struggle against war alone and go towards the higher level of proletarian revolution. This revolutionary wave was above all built up around the struggle against the war;

* the development of the mass strike through the unification of political and economic demands remained very fragile and thus did little to push it onto a higher level of consciousness;

* the revolutionary peak was on the point of being reached. The movement no longer had the same dynamic after the defeat of the struggles in Germany and Central Europe. Even if the wave continued it had lost the force it had from 1919-1920;

* the Soviet Republic in Russia remained cruelly isolated. It was the sole revolutionary bastion with all that this implied in favour of a regression in consciousness both within Russia and the rest of the world.

A foundation in an urgent situation which opened the door to opportunism

The revolutionary milieu came out of the war in a weakened state

"The workers' movement on the eve of the first imperialist world war was in a state of extreme division. The imperialist war had broken the formal unity of the political organisations that claimed to be part of the proletariat. The crisis of the workers’ movement, which already existed beforehand, reached its culminating point because of the fact of the world war and the positions to take up in response to it. All the marxist, anarchist and trade union parties and organizations were violently shaken by it. Splits multiplied. New groups arose. A political delimitation was produced. The revolutionary minority of the 2nd International represented by the Bolsheviks, the German left around Luxemburg and the Dutch Tribunists, who already were not very homogeneous, did not simply face a single opportunist bloc. Between them and the opportunists there was a whole rainbow of political groups and tendencies, more or less confused, more or less centrist, more or less revolutionary, representing the general shift of the masses who were breaking with the war, with the Sacred Union, with the treason of the old parties of social democracy. We see here a process of the liquidation of the old parties whose downfall gave rise to a multitude of groups. These groups expressed less the process of the constitution of the new party than the dislocation m the liquidation, the death of the old party. These groups certainly contained elements for the constitution of the new party but in no way formed the basis for it. These currents essentially expressed the negation of the past and not the positive affirmation of the future. The basis for the new class party can only reside in the former left, in its critical and constructive work, in the theoretical positions and programmatic principles which the left had been elaborating for the 20 years of ITS FRACTIONAL EXISTENCE AND STRUGGLE inside the old party." [6]

Thus the revolutionary milieu was broken apart, composed of groups lacking clarity and displaying a good deal of immaturity. Only the left fractions of the 2nd International, the Bolsheviks, the Tribunists, the Spartacists (in part only because they were also heterogeneous or even divided) were up to it and were based on solid ground for the foundation of the new party.

Moreover a good number of militants lacked political experience. Among the 43 delegates to the founding congress whose ages were known, five were in their twenties, 24 their thirties and only one was older than fifty[7]. Out of the 42 delegates whose political trajectory could be traced, 17 had joined social democratic parties before the Russian revolution of 1905, whereas 8 only became active socialists after 1914[8].

Despite their passion and enthusiasm, the indispensable experience in such circumstances was very much lacking amongst them.

Disagreements among the proletariat's avant-garde

As the FFCL already underlined in 1946, "It is undeniable that one of the historic causes of the victory of the revolution in Russia and its defeat in Germany, Hungary and Italy resides in the existence of the revolutionary Party at a decisive moment in the former and its absence or its incompletion in the latter." The foundation of the 3rd International was deferred for a long time by the various divisions inside the proletarian camp during the episode of revolution. In 1918-19, and quite conscious that the absence of the party was an irredeemable weakness for the victory of the world revolution, the avant-garde of the proletariat was unanimous on the imperious necessity to set up a new party. However, there was no agreement on when to do it and above all on the approach to adopt. While the great majority of communist organisations and groups were favorable to the briefest delay, the KPD and particularly Rosa Luxemburg and Leo Jogiches opted for an adjournment, considering that the situation was premature, that the communist consciousness of the masses remained weak and that the revolutionary milieu also lacked clarity[9]. The KPD delegate to the congress, comrade Albert, was thus mandated to defend this position and not to vote for the immediate foundation of the Communist International.

"When it was said to us that the proletariat needed a political centre in its struggle, we could say that this centre already existed and that all the elements which were found at the base of the system of councils had already broken with elements of the working class which went towards the democratic bourgeoisie: we noted that everywhere a rupture was being prepared and it is about to be realised. But a Third International must not only be a political centre, an institution in which the theoreticians discuss with one another with warm words, it must be the basis of an organisational power. If we want to make the Third International an efficient instrument of struggle, if we want to make it a means for combat, then the necessary conditions have to exist. Thus, in our opinion, the question mustn't be approached and discussed from an intellectual point of view; we have to ask if the basics of the organisation concretely exist. I've always had the feeling that the comrades who are pushing so strongly for its foundation have been greatly influenced by the evolution of the 2nd International and that they wanted, after the Berne Conference, to impose it on the current enterprise. That seems less important to us and when it's said that clarification is necessary, otherwise indecisive elements will rally to the Yellow International, I say that the founding of the 3rd International will not bring back the elements who are re-joining today's 2nd, and that if they go there despite everything, then that's their place."[10]

As we see, the German delegate warned of the danger of founding a party by compromising on principles and on programmatic and organisational clarification. Although the Bolsheviks took the concerns of the KPD very seriously, it was in no doubt that they were caught up in a race against time. From Lenin to Zinoviev, through to Trotsky and Rakovsky, all insisted on the importance of making all the parties, groups, organisations or individuals who claimed to be more or less close to communism and the soviets join the new International. As noted in a biography of Rosa Luxemburg: "Lenin saw in the International the means to help various communist parties to set themselves up and strengthen themselves"[11] through the decantation produced by the struggle against centrism and opportunism. For the KPD, it was first of all a question of forming "solid" communist parties which had the masses behind them before endorsing the creation of the new party.

A method of foundation which did not arm the new party

The composition of the congress is both the illustration of the precipitation and the difficulties that it imposed on revolutionary organisations at the time. Out of 51 delegates taking part in the work, taking account of lateness, early departures and brief absences, around forty were Bolshevik militants from the Russian party but also the Latvian, Lithuanian, Byelorussian, Armenian and eastern Russian parties. Outside of the Bolshevik Party, only the communist parties of Germany, Poland, Austria and Hungary had a real existence.

The other forces invited to the congress were a multitude of organisations, groups or elements that were not openly "communist" but products of a process of decantation within social democracy and the trade unions. The letter of invitation to the congress appealed to all the forces, near or far, which supported the Russian revolution and seemed to have the will to work for the victory of the world revolution:

"10. It is necessary to ally ourselves with these elements of the revolutionary movement which, although they did not belong to the socialist parties before, today placed themselves on the whole on the terrain of the dictatorship of the proletariat under the form of the power of the councils. In the first place we refer here to the syndicalist elements of the workers' movement.

* 11. Finally, it’s necessary to win over all the proletarian groups and organisations that, without openly rallying to the revolutionary current, show a tendency in this direction."[12]

This approach led to several anomalies which exposed a lack of representation of a part of the congress. For example, the American Boris Reinstein didn't have a mandate from his Socialist Labour Party. S. J. Rutgers from Holland represented a league for socialist propaganda. Christian Rakovsky [13] was supposed to represent the Balkan Federation, the Bulgarian “Narrows” and the Romanian CP. But he'd had no contact with these three organisations since 1915-16[14]. Consequently, despite appearances, this founding congress was at root perfectly representative of the lack of consciousness within the world working class.

All these elements show that a large part of the revolutionary avant-garde's objective was quantity to the detriment of a prior clarification on organisational principles. This approach turned on its head the conception which the Bolsheviks had developed over the last fifteen years. And this is what the FFCL had already noted in 1946: "As much as the "strict" method of selection on the most precise principled bases, without taking into account immediate numerical success, allowed the Bolsheviks to build a Party which, at a decisive moment, was able to integrate and assimilate into itself all the energies and revolutionary militants of other currents and finally lead the proletariat to victory, so the "loose" method, immediately concerned above all with bringing together the largest numbers at the expense of programmatic precision and principles, had to lead to the constitution of the mass party, a real colossus with feet of clay which fell to its defeat under the domination of opportunism. The formation of the class party turns out to be infinitely more difficult in the advanced capitalist countries - where the bourgeoisie possesses numerous means to corrupt the consciousness of the proletariat – than was the case in Russia."

Blinded by the certitude of the imminent victory of the proletariat, the revolutionary avant-garde enormously underestimated the objective difficulties which stood in front of them. This euphoria led them to compromise the "strict" method for the construction of the organisation that the Bolsheviks in Russia and in part the Spartacists in Germany had defended before everything. They considered that the priority of work had to be given to a great revolutionary coming-together, countering on the way the Yellow International which a few weeks before had re-formed in Berne. This "loose" method relegated the clarification of organisational principles to the status of an annex. Little importance was given to the confusions that could be brought in by groups integrated into the new party; the struggle would take place within it. For now, the priority was given to the regroupment of the greatest numbers.

This "loose" method turned out to be heavy with consequences since it weakened the CI in the organisational struggles to come. In fact the programmatic clarity of the first congress was circumvented by the opportunist push in the context of the weakening and the degeneration of the revolutionary wave. Within the CI fractions of the left emerged which criticised the insufficiencies of the rupture with the 2nd International. As we will see in a following piece, the positions defended and elaborated by these groups responded to the problems raised in the CI by the new period of the decadence of capitalism.

(to be continued)

Narek, March 4, 2019.

[1] The Berne Conference of 1919 was "an attempt to resuscitate the corpse of the Second International", to which the "Centre" had sent representatives.

[2] For a greater development see our article https://en.internationalism.org/content/3066/1919-foundation-communist-i... [4] International Review, no. 57, spring 1989.

[3] Internationalisme. "A propos du Premiere Congres du Parti Communiste Internationaliste d'Italie", no. 7, Jan-Feb 1946.

[4] Lenin, Works, t.XXVIII, p. 451.

[5] Dorrenbach was the commander of the People’s Naval Division in Berlin, 1918. After the January defeat, he took refuge in Brunswick and then Eisenach. He was arrested and executed in May 1919.

[6] Internationalisme, "A propos du Premier Congres du Parti Communiste d'Italie", no. 7, Jan-Feb, 1946.

[7] Founding of the Communist International: The Communist International in Lenin's Time. Proceedings and Documents of the First Congress: March 1919, Edited by John Riddell, New York, 1987. Introduction, page 19.

[8] Ibidem.

[9] It's this mandate that the KPD gave (in the first weeks of January) to their delegate to the founding congress. This is no way meant that Rosa Luxemburg for example was opposed to the foundation of an International - far from it.

[10] Intervention of the German delegate March 4, 1919, in Premier Congres de l'Internationale Communiste, integral texts published under the direction of Pierre Broué, Etudes et Documentation Internationales, 1974.

[11] Gilbert Badia, Rosa Luxemburg, Journalist, Polemicist, Revolutionary, Editions Sociales, 1975.

[12] "Letter of invitation to the Congress", Op. Cit. First Congress of the International.

[13] One of the most influential and determined delegates in favour of the immediate foundation of the CI.

[14] Pierre Broué, History of the Communist International (1919-1943), Fayard, 1997, p. 79 (in French).

Rubric:

Internationalisme nº 7, 1945: The left fraction - Method for forming the party

- 367 reads

Introduction

To stimulate discussion around the formation of the future world party of the revolution, we are publishing two chapters of an article from Internationalisme no. 7 from January 1946, entitled “On the First Congress of the Internationalist Communist Party of Italy”. The review Internationalisme was the theoretical organ of the French Fraction of the Communist Left (FFCL), the group that was politically the most clear in the period immediately after the Second World War. In 1945 the Fraction transformed itself into the Gauche Communiste de France in order to avoid confusion following a split by militants in France who took the same name for their group as the French Fraction

This article (which we will be publishing in full on our website), basing itself on the lessons of the degeneration of the Third International, develops on the criteria which have to apply to the constitution of a future world party. The two chapters published in this Review – the first, “The Left Fraction” and the sixth, “Method for forming the party” – look at the political questions posed since the foundation of the Third International and provide a coherent argument for understanding them. They build a bridge between the post World War One period and the period of the Second World War, on the basis of the balance sheet drawn up by the Italian Fraction in the 1930s, whereas the other chapters are more devoted to a polemic with specific currents of the 1940s, such as the RKD (Revolutionäre Kommunisten Deutschlands, a group of former Trotskyists from Austria) and Vercesi. These chapters are also very interesting but would not fit into a printed Review.

Summarised briefly, the criteria for the formation of the party are, on the one hand, a course open to the revival and offensive struggle of the proletariat, and, on the other hand, the existence of a solid programmatic basis for the new party.

At that moment, after the first congress of the Internationalist Communist Party, held at the end of December 1945 in Turin, the GCF considered that the first condition – a new favourable course – had been satisfied. Thus, on this basis, they saluted the transformation of the Italian Fraction “by giving birth to a new party of the proletariat” . It was only later, in 1946, that the GCF recognised that the period of counter-revolution was not over and that the objective conditions for the formation of the party were absent. Consequently it stopped publication of its agitational paper L’Etincelle, considering that the perspective for a historical resurgence of class struggle was not on the agenda. The last issue of L’Etincelle came out in November 1946.

At the same time, the GCF severely criticised the method used for the constitution of the Italian party, via “an addition of currents and tendencies” on a heterogeneous basis (“Method for forming the party”), in the same way as it criticised, in the same chapter, the method for forming the CI, an “amalgamation around a programme that had deliberately been left incomplete”. And such a programme could only be an opportunist one[1], which turned its back on the method which had been applied to the construction of the Bolshevik Party.

The merit of this article in Internationalisme is that it insists on the rigour needed around the adoption of a programme, which did not exist in the party that had just been formed in Italy. This article – written about a quarter of a century after the foundation of the Comintern, and a few weeks after the congress of the Internationalist Communist Party – was certainly the most consistent critique of the way the foundation of the Communist International went against the methods of the Bolshevik Party. Internationalisme was also the only publication of the milieu of the communist left at that time to highlight the opportunist approach of the Internationalist CP.

In this sense, the GCF is an illustration of the continuity with the method of Marx and Engels in the foundation of the German Social Democratic Party at Gotha in 1875 (cf The Critique of the Gotha Programme), when they rejected the confused and opportunist basis on which the SAPD was founded. Continuity also with the attitude of Rosa Luxemburg faced with the opportunism of the revisionist Bernstein the German Social Democracy 25 years later, but also with that of Lenin on organisational principles against the Mensheviks. Continuity, finally, with the attitude of Bilan faced with the opportunism of the Trotskyist current in the 1930s. It was thanks to this intransigence in the defence of programmatic positions and organisational principles that elements coming out of the current around Trotsky (such as the RKD) were able to move towards the defence of internationalism during and after the Second World War. Holding high the banner of internationalism against the “partisans”, intransigently defending internationalism against opportunism was thus a condition for the internationalist forces to find a political compass.

In this presentation we should make more precise a formulation concerning the Spartakusbund during the First World War:

“The experience of the Spartakusbund is highly edifying on this point. The latter’s fusion with the Independents did not, as they hoped, lead to the creation of a strong class party but resulted in the Spartakusbund being swamped by the Independents and to the weakening of the German proletariat. Before her murder, Rosa Luxemburg and other Spartakusbund leaders recognized the error of fusing with the Independents and tried to correct it. But this error was not only maintained by the CI in Germany, but it became the practical method for forming Communist Parties in all countries, imposed by the CI”.

It’s not quite right to talk about the fusion of the Spartakusbund with the USPD. The USPD was formed by the SAG (Sozialistische Arbeitsgemeinschaft – Socialist Working Group); the Internationale group (the Spartakusbund) was integrated into it. But this was not strictly speaking a fusion, which would imply the dissolution of the organisation that has fused with another. In fact the Spartakusbund maintained their organisational independence and their capacity for action while giving themselves the objective of drawing this formation towards their positions as a left wing inside it. Very different was the approach of the CI through the fusion of different groups within a single party, abandoning the necessary process of selection through an addition, with “principles sacrificed t numerical mass”.

We should also rectify a factual error in this article where it says “In Britain, the CI demanded that the communist groups join the Independent Labour Party to form a mass revolutionary opposition inside this reformist party”.

In fact, the CI called for integration of communists into the Labour Party itself! This error of detail in no way alters the basic argument of Internationalisme.

14.5.19

[1] See our article “Battaglia Comunista -On the origins of the Internationalist Communist Party”, IR 34

On the First Congress of Internationalist Communist Party of Italy

1. The left fraction

At the end of 1945, the first congress of the young, recently constituted Internationalist Communist Party of Italy took place.

This new Party of the proletariat didn't spring out of nothing. It was the fruit of a process which began with the degeneration of the old Communist Party and the Communist International. This opportunist degeneration brought about a historic response from the class within the old party: the Left Fraction.

As all the communist parties set up following World War I, the Communist Party of Italy, at the moment of its formation, contained both revolutionary and opportunist currents.

The revolutionary victory of the Russian proletariat and of the Bolshevik Party of Lenin in October 1917, through the decisive influence that it exercised on the international workers' movement, accelerated and precipitated the organisational political contrasts and delimitations between revolutionaries and the opportunists who cohabitated in the old Socialist parties of the IInd International. The 1914 war had broken this impossible unity between the old parties.

The October revolution sped up the constitution of new parties of the proletariat but, at the same time, the positive influence of the October revolution contained some negative elements.

By rushing the formation of new parties, it prevented a construction on the basis of clear, sharp principles and a revolutionary programme. This could only be elaborated following an open and intransigent political struggle which eliminated the opportunist currents and the residues of bourgeois ideology.

With the lack of a revolutionary programme, the Communist Parties were set up too hastily on the basis of a sentimental attachment to the October revolution, opening up too many fissures for the penetration of opportunism in the new proletarian parties.

Also, from their foundation, the CI and the communist parties of various countries were caught up in the struggle between revolutionaries and opportunists. The ideological struggle - which has to come before and be a precondition for the party, which is protected from the opportunist gangrene only through the enunciation of principles and the construction of the programme - only took place after the constitution of the parties. As a result, not only did the communist parties introduce the germ of opportunism from the beginning, but it also made the struggle more difficult for the revolutionary currents against the opportunism that survived and was hidden within the new party. Each defeat of the proletariat modified the balance of forces against the proletariat, inevitably producing the strengthening of opportunism within the party, which in its turn became a supplementary factor in further proletarian defeats.

If the development of the struggle between the currents in the party became so sharp so quickly it's because of the historical period. The proletarian revolution exited from the spheres of theoretical speculation. From the distant ideal that it was yesterday, it became a problem of immediate practical activity.

Opportunism was no longer manifested in bookish theoretical elaborations acting as a slow poison on the brains of the proletarians. At the time of intense class struggle it had immediate repercussions and was paid for with the lives of millions of proletarians and bloody defeats of the revolution. As opportunism strengthened itself in the CI and its parties it was the main card of and an auxiliary to capitalism against the revolution because it meant the strengthening of the enemy class within the most decisive organ of the proletariat: its party. Revolutionaries could only oppose opportunism by setting up their Fraction and proclaiming a fight to the death against it. The constitution of the Fraction meant that the party had become the theatre of confrontation between opposed and antagonistic class expressions.

It was the war-cry of revolutionaries to save the class party, against capitalism and its opportunist and centrist agents who were trying to take hold of the party and turn it into an instrument against the proletariat.

The struggle between the Fraction of the Communist Left and the centrist and right-wing fractions for the party isn't a struggle for "leadership" of the apparatus but is essentially programmatic; it is an aspect of the general struggle between revolution and counter-revolution, between capitalism and the proletariat.

This struggle follows the objective course of situations and the modifications of the rapport de force between the classes and is conditioned by the latter.

The outcome can only be the victory of the programme of the Fraction of the left and the elimination of opportunism, or the open betrayal of a party which has fallen into the hands of capitalism. But whatever the outcome of this alternative, the appearance of the Fraction means that the historical and political continuity has definitively passed from the party to the fraction and that it's the latter alone that henceforth expresses and represents the class.

Just as the old party can only be salvaged by the triumph of the fraction, the same goes for the alternative outcome of the betrayal of the old party, completing its ineluctable course under the leadership of centrism. Here the new party can only be formed on the programmatic basis provided by the fraction.

The historic continuity of the class through the process Party-Fraction-Party, is one of the fundamental ideas of the International Communist Left. This theory was a theoretical postulate for a long time. The formation of the PCI in Italy and its first congress provide the historic confirmation of this postulate.

The Italian Left Fraction, after a struggle of twenty years against centrism, achieved its historic function by transforming itself and giving birth to a new party of the proletariat.

Method for forming the party

While it is correct to say that the constitution of the party is determined by objective conditions and cannot be the emanation of individual will, the method employed in constituting the party is more directly subordinated to the “subjectivism” of the groups and militants who take part in it. It is they who feel the necessity for constituting the party and translate this into action. The subjective element thus becomes a decisive element in this process and in what follows; it marks the whole orientation for the ulterior development of the party. Without falling into a helpless fatalism, it would be extremely dangerous to ignore the grave consequences that result from the way in which human beings carry out the tasks whose objective necessity they have become aware of.

Experience teaches us the decisive importance of the method for the constitution of the party. Only the ignorant or the hare-brained, those for whom history only begins with their own activity, can have the luxury of ignoring the whole rich and painful experience of the 3rd International. And it’s no less serious to see very young militants, who have only just arrived in the workers’ movement and the communist left, not only being content in their ignorance but even making it the basis of their pretentious arrogance.

The workers’ movement on the eve of the first imperialist world war was in a state of extreme division. The imperialist war had broken the formal unity of the political organisations that claimed to be part of the proletariat. The crisis of the workers’ movement, which already existed beforehand, reached its culminating point because of the world war and the positions that were needed to take up in response to it. All the marxist, anarchist and trade union parties and organizations were violently shaken by it. Splits multiplied. New groups arose. A political delimitation was produced. The revolutionary minority of the 2nd International represented by the Bolsheviks, the German left around Luxemburg, and the Dutch Tribunists, who already were not very homogeneous, did not simply face a single opportunist bloc. Between them and the opportunists there was a whole rainbow of political groups and tendencies, more or less confused, more or less centrist, more or less revolutionary, representing the general shift of the masses who were breaking with the war, with the Sacred Union, with the treason of the old parties of social democracy. We see here a process of the liquidation of the old parties whose downfall gave rise to a multitude of groups. These groups expressed less the process of the constitution of the new party than the dislocation, the liquidation, the death of the old party. These groups certainly contained elements for the constitution of the new party but in no way formed the basis for it. These currents essentially expressed the negation of the past and not the positive affirmation of the future. The basis for the new class party could only reside in the former left, in its critical and constructive work, in the theoretical positions and programmatic principles which the left had been elaborating for the 20 years of its existence and struggle as a fraction inside the old party.

The October 1917 revolution in Russia provoked great enthusiasm in the masses and accelerated the process of the liquidation of the old parties who had betrayed the working class. At the same time, it posed very sharply the problem of the constitution of the new party and the new International. The old left, the Bolsheviks and the Spartacists, were submerged by the rapid development of the objective situation, by the revolutionary push of the masses. Their precipitation in building the new party corresponded to and was the product of the precipitation of revolutionary events around the world. It is undeniable that one of the historical causes of the victory of the revolution in Russia and of its defeat in Germany, Hungary and Italy lies in the existence of the revolutionary party at the decisive moment in the first country and its absence or incomplete character in the others. Thus the revolutionaries tried to overcome the gap between the maturation of the objective situation and the immaturity of the subjective factor (the absence of the party) through a broad gathering of politically heterogeneous groups and currents and proclaiming this gathering as the new party.

Just as the “narrow” method of selection on the most precise principled bases, without taking into account immediate numerical success, enabled the Bolsheviks to build a party which, at the decisive moment, was able to integrate and assimilate all the revolutionary energies and militants from other currents and ultimately lead the proletariat to victory, so the “broad” method, with its concern above all to rally the greatest possible numbers straight away at the expense of precise principles and programme, led to the formation of mass parties, real giants with feet of clay which were to fall under the sway of opportunism after the first defeat they went through. The formation of the class party proved to be infinitely more difficult in the advanced capitalist countries, where the bourgeoisie possesses a thousand means for corrupting the consciousness of the proletariat, than it was in Russia.

Because of this, the CI thought it could get round the difficulties by resorting to other methods than those which had triumphed in Russia. The construction of the party is not a question of skill or savoir-faire but essentially a problem of programmatic solidity.

Faced with the enormous power of ideological corruption wielded by capitalism and its agents, the proletariat can only put forward its class programme with the greatest rigour and intransigence. However slow this path towards building the party might seem, revolutionaries can follow no other, as the experience of past failures has shown.

The experience of the Spartakusbund is highly edifying on this point. The latter’s fusion with the Independents did not, as they hoped, lead to the creation of a strong class party but resulted in the Spartakusbund being swamped by the Independents and to the weakening of the German proletariat. Before her murder, Rosa Luxemburg and other Spartakusbund leaders recognized the error of fusing with the Independents and tried to correct it. But this error was not only maintained by the CI in Germany, but it became the practical method for forming Communist Parties in all countries, imposed by the CI.

In France, the CI “created” the Communist Party by imposing the amalgamation and unification of groups of revolutionary syndicalists, the internationalists of the Socialist Party and the rotten, corrupt centrist tendency of the parliamentarians, led by Frossard and Cachin.

In Italy, the CI obliged Bordiga’s abstentionist fraction to found a single organisation with the centrist and opportunist tendencies of Ordino Nuovo and Serrati.

In Britain, the CI demanded that the communist groups join the Independent Labour Party to form a mass revolutionary opposition inside this reformist party,.

In sum, the method used by the CI in the “construction” of Communist Parties was everywhere opposed to the method which proved effective in the building of the Bolshevik Party. It was no longer the ideological struggle around the programme, the progressive elimination of opportunist tendencies which, through the victory of the most consistently revolutionary fraction, served as the basis for the construction of the party. Instead the basis was an addition of different tendencies, their amalgamation around a programme that had deliberately been left incomplete. Selection was replaced by addition, principles sacrificed for numerical mass.