April 2019

- 78 reads

Anti-Semitism dispute in the Democratic Party: The contradictions of bourgeois identity politics

- 434 reads

This article, written by a close sympathizer in the US, looks at the adoption of “identity politics” by the left wing of the bourgeoisie – an international phenomenon, but one which, for historical reasons, has reached a particularly advanced level in America. The endless divisions created by this kind of politics are certainly a means for exacerbating divisions within the working class, but they can also bring numerous problems for the bourgeoisie, whose control of the political apparatus is growing less and less secure.

When asked what the greatest achievement of her time as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom was, Margaret Thatcher once quipped it was how she forced the Labour Party to change. By this she meant that even though Labour defeated the Tories in the 1997 election, the party that took over government was no longer the old “social democratic” institution it was when she took office a decade and a half earlier. It had been transformed during her time in office into New Labour, a party thoroughly committed to the neo-liberal consensus.

When the light finally goes out on Donald Trump’s Presidency, one wonders if a similar thing might be said about him. Will the most meaningful effect of his time in office be a change in the political face of the Democratic Party? Has Trumpism had something of the opposite effect of Thatcher’s domestication of Labour, “radicalizing” the Democratic Party to such an extent that the old slightly left of center party of Bill Clinton and Barack Obama has now become a “socialist” party moving ever so dramatically to the left? Will the Republicans, after a decade of Tea Party rage and the rise of Trumpist populism within its ranks, start to look like the rational adults in the room to the suburban core of the American electorate once again?

Obviously, reality is quite a bit more complicated than this emerging media narrative would suggest. As quantum mechanics teaches us, causality can often be difficult to parse out. If the Democrats’ apparent lurch to the “left” is one of the unitentended effects of Trumpism, it is nevertheless the case that Trump himself is an effect of even deeper historical, social and political forces that precede his candidacy.

Moreover, the narrative of the Democratic Party moving steadily “leftwards,” towards “socialism,” conceals a number of contradictions permeating the political and social field today that makes the Democratic Party’s electoral coalition extremely volatile and increasingly prone to internal strife. If the opposition, or “resistance,” to Trump, keeps the party united on the immediate need to end his Presidency in 2020 (or sooner), this only hides deeper fractures that are likely to erupt as soon as the next Democrat assumed the Presidency.

In the 2018 midterm elections, Democrats rode popular revulsion at President Trump to a stunning take over of the House of Representatives. The Democrats were able to capitalize on a wave of female candidates running for office in something like a “Me Too” repudiation of Trumpist disdain for women. Nancy Pelosi, who is now painted by the media as a kind of second “Iron Lady,” is once again Speaker of the House. The Democrats had no hesitations about selling their candidates in the terms of “identity politics.” The freshman class of representatives elected on the Democratic ticket was the “most diverse ever,” they have frequently reminded us, representing a stark rejection of all the bad “isms” that Trump represents.

Among the freshman class of representatives are: Rashida Tlaib (Palestinian-American from Michigan), Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (a New Yorker of Puerto Rican descent, who unseated the fourth ranking member of the Democratic House delegation in a primary), Ayanna Pressley (African-American from Massachusetts, another primary victor over an establishment Democrat) and Ilhan Omar (Somali-American from Minnesota, who often proudly wears an hijab to work in Congress). Some of this group, who call themselves the “Squad,” describe their politics as “socialist,” others as mere “progressive,” but all readily engage in the celebration of their “identities” as core features of their politics and the meaning and purpose behind their lives and work in Congress.

If the stunning primary victories by leftists like Ocacio-Cortez and Pressley, and the subsequent media attention they have received, undoubtedly worry establishment Democrats, they nevertheless welcome the opportunity to promote these young “women of color” as evidence of their party’s moral opposition to the Trump administration. They have repeatedly reminded us that their mid-term election victory made history by bringing the first two female Muslims to the halls of Congress. In February, Pelosi herself appeared in a photo op with members of the Squad for the cover of Rolling Stone magazine. What better contrast to the Trump administration could the Democrats’ make than to champion their new and highly diverse crop of freshman legislators that include members from communities Trump is said to hate: Hispanics and Muslims.

Nevertheless, less than two months into the new Congress, Democrats’ attempts to marketize the diversity of their new members and politicize their identities has hit a bit of a snag. Congresswomen Tlaib and Omar have both been accused of making anti-Semitic comments in their criticisms of Israel. First Tlaib suggested that supporters of Israel were more loyal to that country than America.[1] Then, a 2012 tweet from Omar surfaced in which she wrote that “Israel has hypnotized the world;” on top of this, she authored tweets suggesting that the US’s staunch support for Israel was mostly down to the lobbying efforts of the American Israel Public Affairs Committee (AIPAC), suggesting that it was “All about the Benjamins, baby!” [2]

Omars’s tweets led to an immediate outpouring of condemnation from Jewish groups and Jewish members of Congress, both Democrat and Republican, who accused her of dealing in age-old anti-Semitic tropes. Senior Democratic leaders quickly rejected her statements and urged her to apologize. Omar bowed to the leadership, tweeting out an apology that acknowledged “Anti-Semitism is real.” However, just a week later, she was caught on camera at a fundraising event, denouncing “The political influence in this country that says its OK to push for allegiance to a foreign power.” [3]

Condemnation from senior Democrats was again swift, with Eliot Engel the chair of the House Foreign Relations Committee (on which Omar sits) denouncing her latest comments as “vile anti-Semitic slurs.”[4] Momentum built over the weekend of March 2nd for a formal House resolution rebuking anti-Semitism, but curiously early in the next week a delay in bringing a motion to the house floor suggested the Democratic caucus was far from united on what to do about Omar’s latest comments. Moreover, this time Omar did not back down. She issued no apology. Realizing that much of leftist social media had her back, she appeared ready this time to fight the Democratic leadership over the issue of support for Israel, backed up by an emerging consensus from leftists that she was being unfairly targeted for correctly denouncing Israeli policy and Israeli influence in Washington.

What started as a brief delay by Democratic leadership to “get the language right” on the resolution, turned into a veritable political debacle for the party leadership by mid-week. Legacy media began to worry that Pelosi was losing control of her caucus, while more credentialed commentators fretted a coming “Corbynization” of the Democratic Party. A near rebellion ensued, led by “progressives,” angry from their perception that justified criticism of Israel and its lobby in Washington were being considered “anti-Semitic,” and the Congressional Black Caucus (CBC), dismayed over what looked like an attempt to gang up on one of their own. Both groups balked at leadership’s attempt to bring a resolution calling out Omar and specifically denouncing anti-Semitism to the House floor.

Voices within the party begin to emerge defending Omar, including House Majority whip Jim Clyburn, who suggested Omar’s comments must be understood in light of her experience and pain as an immigrant refugee. Presidential candidates Kamala Harris worried about Omar’s safety after posters connecting her to the 9/11 terrorist attacks appeared in the West Virginia State House and even Bernie Sanders opined that Omar was being unfairly targeted for criticizing Israel. Media star and socialist celebrity Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez jumped to Omar’s defense, suggesting that any denunciation of anti-Semitism that did not also denounce the anti-Latino bias of Immigrations and Customs Enforcement (ICE) should not go forward.

Apparently, there was now a political dynamic afoot in the Democratic Party that makes an outright rejection of perceived anti-Semitic tropes controversial, without watering it down into a near meaningless condemnation of all things bad. There was simply now no consensus to condemn the specific act of questionable comments from one of their own Congresswomen, without denouncing all forms of bigotry.

The immediate drama concluded with the House voting on a broad condemnation of multifarious forms of “hate,” not specifically mentioning Omar. Over 20 Republicans voted against the measure, with most denouncing it as a cowardly farce. Days later, in typical Trumpian overstatement, the President pronounced the Democrats were now an “anti-Jewish” party.[5]

Whatever the President’s hyperbole, this episode certainly reveals growing tensions within the Democratic Party’s political and electoral collation. The Democrats, whatever their continued united opposition to Trump, appear more and more fractured. With each episode of intra-party fighting, they begin to resemble a loose coalition of competing interest groups suspicious of one another, held together only by the flimsy sticky tape of anti-Trumpism. Barely two months after retaking the House, with a Presidential election against an extremely unpopular President on the horizon, the Democrats are having trouble containing the inevitable political fissures resulting from an increasing reliance on “identity politics” as their legitimating ideology.

Anti-Semitism, “Intersectionality” and the Neo-Liberal Left:

In the span of just several weeks, Omar’s tweets and recorded comments, from 2012 to the present, ran the gamut from accusing Israel of pulling off mass hypnosis, to suggesting that the American government was bought off by Israeli-Jewish money and accusing those who support Israel of having “dual allegiances.”[6] Earlier Congresswoman Tlaib had also made suggestions of conflicted loyalities.

We won’t get into the metaphysical debate that has been playing out in the media over the last several weeks about whether the Congresswomen’s comments were really anti-Semitism dressed up as criticisms of Israeli policy or were really fair criticisms of Israeli policy unfairly attacked as anti-Semitism. It’s pretty clear on this score that in a world defined more and more by ideological polarization and motivated reasoning people are going to see what they want to see in these statements. Suffice it say, while themes of “hypnosis,” political bribery and dual loyalty run right up to the line of some of the worst anti-Semitic tropes that have given rise to pogroms and even the Holocaust itself, Omar’s comments have been generally phrased in a way to leave her true personal intentions debatable. [7]

Nevertheless, it is also clear that the recent row in the Democratic Party over anti-Semitism is only the latest episode in a growing trend towards such provocative anti-Israel activism in the name of “anti-imperialism” emanating from elements associated with the left-wing of the left-of-center parties in major Western states.[8] The long campaign over anti-Semitism in the British Labour Party is the best-known example, which the ICC has previously analyzed here.[9] However, what is most important in the recent controversy surrounding the Democratic Party is the extent to which the underlying ideology of “identity politics,” which has formed the core of the party’s message for some time, has now seemingly come back to bite it in dramatic fashion.

With the ascendancy to power of Bill Clinton, backed by the Democratic Leadership Conference (DLC), in the early 1990s, the Democratic party’s underlying ideological justification began to shift away from being the “party of the working class,” in close alliance with the unions, towards becoming the party of educated professionals in alliance with minority and immigrant communities. Although the Democrats have retained the formal alliance of most unions, the party has been hemorrhaging electoral support from blue-collar whites since at least the so-called “Reagan Revolution” of the early 1980s.

The Presidencies of Clinton and later Obama cemented this process, so that by the time Hillary Clinton was nominated for the Presidency in 2016, the Democrats had largely become the party of professionals that eschewed economic messaging towards the working class in favor of promoting racial, ethnic, gender and other forms of identity “diversity” and “equity” and championing the rights of immigrants. The Democrats’ underlying ideology became less about advancing economic programs for improvement of all and more about leveling the playing field in the neo-liberal meritocratic quest for self-improvement. Universal programs were generally frowned upon, while racially targeted measures to supposedly “set the playing right” became the party’s focus.

Barack Obama’s abandonment in office of universal “Medicare-for-All,” in favor of a convoluted private health care delivery system enforced through an individual mandate—a plan originally designed by policy wonks at the free-market Heritage Foundation and championed by Republican Governors—demonstrated the priorities and commitments of the Democratic establishment.

Democrats became the party of the “risk society,” albeit one that was supposedly balanced towards equality of opportunity for all the diverse identity groups that now make-up American society. This turn was theorized in 2002 by the political scientists Ruy Teixeira and Jonathan Judis, whose book The Emerging Democratic Majority,[10] laid out a strategy for building an unassailable electoral majority to rival FDR’s New Deal Coalition. This involved appealing to the young, professionals and the traditionally marginalized elements of American society, who it was argued would only grow in number, primarily as a result of increased immigration.

Not surprisingly, by adopting such a “demographic strategy,” Democrats only hastened the flight of blue-collar whites to the Republicans. While enough of these voters remained loyal to the party to help elect Obama in 2008 and 2012 in the midst of economic crisis, the apparent betrayal of their interests by the Democratic establishment in the post-crisis years led to an increased openness to the kind of populism trafficked by Trump. When Hillary Clinton referred to Trump supporters as “deplorables,” in the 2016 campaign, it only confirmed for many working class whites that the Democratic Party would not advance their interests.

Meanwhile, as the Republican Party was transformed by Trump in a populist direction, taking up the economic and cultural grievances of the Rust Belt working class, the Democratic Party was accelerating into a headlong flight into “identity politics,” backed up by academic theories of so-called “intersectionality.” In the intersectional worldview, the multifarious identity grievances are supposed to overlap with one another to produce a kind of coalition of the oppressed against white male privilege and to advance the recognition of sub-altern identities.

In this worldview, standing up to speak about oppression is a function of certain innate qualities of individuals that give them moral authority to express the interests of the group identities they claim. The more sub-altern identities one can assert, the more authority one has to speak, and the more personal virtue as a multiply oppressed person one is regarded to hold. Oppression of one’s identity becomes a road to a kind power—a power to speak and define the terms of politics that only the oppressed can have as a function of their “lived experience.”[11] The world is thus divided into oppressors and oppressed in concrete life situations that grant deference to the rights and power of the oppressed to “speak their truth” to power, whether on the stage of national politics or on the micro-level of daily interactions in the lifeworld or in cyberspace.

Intersectionality has long had its academic critics who often derisively describe it as a kind of “oppression Olympics,” and point out the practical difficulties of mitigating just who is an oppressor and who is oppressed in the real world. Moreover, what happens when different kinds of oppression, rather than overlapping, actually come into conflict with one another? Which claims take priority?

Nevertheless, whatever the practical difficulties, the theory and approach were tailor made for the Democratic Party seeking a new legitimating ideology in a world being rapidly remade by neo-liberal capitalism and mass migration. As long as the possible contradictions of intersectionality did not emerge into full view behind the unifying rallying cry of anti-Trumpism then the Democrats could convince themselves they could control the obvious centrifugal tendencies underlying the illusion of a “grand collation of the oppressed.”

However, now, within months of taking power in one house of Congress, the contradictions of this approach are already on full display. Many Democrats who supported Omar initially rejected the idea that her comments were really anti-Semitic, asserting instead that they were reasonable criticisms of Israel and its role in US politics. Of course, this kind of interrogation of claims against a standard of objective reasonableness would seem to violate one of the cardinal rules of intersectionality: it is the oppressed and offended group alone that gets to decide what is offensive speech. Nobody else has the “lived experience” necessary to make this judgment. The fact that there were Jews who defended Omar would not really matter. If some quorum of Jews believed her comments were anti-Semitic, their judgment must be accepted as right. There is no Archimedean point outside of the oppressor-oppressed relationship from which a kind of objective reason can be exercised to pronounce on the legitimacy of the outrage. We must listen to the oppressed and offended group and defer to their judgment. Omar herself seemed to recognize her conundrum at first, walking back her original comments about the role of AIPAC and apologizing for her comments about hypnosis.

But then the intersectional absurdities of the situation hit a new level after Omar’s recorded comments denouncing “dual loyalties” emerged. Faced with a second round of criticism in the span of a week and the threat of an official House resolution denouncing her comments, Omar decided not to apologize this time, but instead play the victim herself. She and Congresswoman Tlaib were being unfairly signaled out for criticism because they were Muslim. Attacking perceived anti-Semitism was thus itself Islamophobic, when it is Muslims making the allegedly anti-Semitic statements.

In a particularly damning illustration of the conundrum into which intersectionality had apparently driven the Democratic Party, Congressman Clyburn defended Omar by comparing her “lived experience” of oppression as a Somali immigrant and former resident of a refugee camp in Kenya to the “lived experience” of Holocaust survivors. Perhaps without knowing what he was doing, Congressman Clyburn—an old school African-American Democrat unlikely to be particularly well versed in the academic intricacies of intersectional theory—confirmed what many had suspected all along: the controversy wasn’t just about Israel and its policies, it was also about the comparative moral weight of Muslim vs. Jewish trauma and pain.

For Clyburn, Omar’s pain was more powerful because it was more recent. Jews were now far removed from the historical reality of the Holocaust. Their group trauma and pain could not compare to Omar’s as a Muslim refugee.[12] Islamophobia thus beats out anti-Semitism in the oppression Olympics and assumes a higher place in the hierarchy of pain and suffering. Of course, just what Omar’s pain as a refugee had to do with her statements was never made clear, other than it may have influenced her poor choice of words somehow. In defending Omar, Clyburn also infantilized her as someone whose personal experience as a sub-altern meant she should not have to take full moral responsibility for having harmed some other oppressed group, whose oppression wasn’t quite so bad anyway. Of course, this only begged another troubling question: can the oppressed also be oppressors in their own right?

Congressman Clyburn’s remarks were revealing in that they demonstrate that in order for Omar’s questionable comments to be mitigated, they either have to be explained away as the effect of some kind of trauma or they have to be placed above the absurd competition of different oppressed groups. One way to do this, which has now been adopted by many of the bourgeois left, is to proffer that Jews are no longer a really oppressed group anyway. In this view, Jews are accepted as “white” in most Diasporic locations and have now, centuries of anti-Semitism aside, become oppressors themselves, as evidenced by their communities’ support for and loyalty to the state of Israel—a state that engages in the ruthless oppression of the Palestinians and its internal Arab minority, violates human rights constantly and has become for all intents and purposed an “apartheid state” in own right that must be overthrown.

This is where the connection between the policies of Israel are tied back to the various Diasporic Jewish communities, through their ability to influence foreign policy in their nations of residence in favor of the Israeli apartheid state, through campaign contributions and other motivated uses of “Jewish money.” Jewish communities’ ability to serve as a kind of “fifth column” of Israeli influence in their nations of residence, something the South African apartheid state couldn’t really rely on, is what makes their loyalties open to question.

Delegitimizing Israel is thus the intended purpose of the so-called Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions Movement (BDS), which seeks to use the model of the struggle against apartheid in South Africa to delegitimize Israel in international public opinion, deprive it of critical support from the West and force it to abandon its supposed policy of “Jewish Supremacy.” The fact that Israel was itself ostensibly founded as a sanctuary for the oppressed Jewish people following the Holocaust is no longer relevant. In line with Congressman Clyburn’s relative minimization of Jewish pain, BDS supporters suggest the Holocaust can no longer be seen as a legitimate reason to support Israel; the moral authority granted from having been the victims of genocide has long been rendered moot by the Israeli state’s subsequent actions against the oppressed Muslim and Arab populations of the region.

Unsurprisingly, the BDS movement has proven hotly controversial. Popular on many college campuses, it still does not count many supporters in the halls of power. Senior Democrats like Senate Minority Leader Chuck Schumer and Senator Ben Cardin loudly oppose it, even sponsoring legislation to penalize companies who advocate it by forbidding them from getting government contracts. Many of BDS’s opponents see it as a thinly veiled attempt to erase the Jewish state from the map - considered to be the anti-Semitic act par excellence. While Democratic Presidential Candidates, especially Bernie Sanders (himself Jewish), have recently increased their willingness to criticize Israel, none has yet endorsed BDS. Although with the election of Omar and Tlaib, there are at least two proponents now in Congress.[13]

Clearly, many people today are increasingly and rightly concerned about the condition of the Palestinian people and the overall nature of Israeli policy. As communists that believe in objective standards of reasonableness, we confirm that it is not in itself anti-Semitic to criticize Israel. But it is also the case that the increasing polarization of society around these issues may be pushing otherwise well meaning critics to seek less than savory allies and to make excuses for those who cross the line into questionable tropes out of a pressure to support one’s perceived anti-imperialist team. There is little reason to expect these trends to mitigate. With President Trump attempting to exploit the turmoil in the Democratic Party over this controversy and to make support for Israel a partisan issue, it is likely that the rancor will only increase, tempting others to cross the line from real criticism into questionable tropes.

It is unlikely that this episode will result in major electoral effects right away: Jews are mostly reliable Democratic voters in the US and it is unlikely many will switch to support Republicans due to outrage over what remains a phenomenon largely isolated to the “progressive” wing of the Democratic party. Nevertheless, it is the case that this episode reveals the tensions and cleavages emerging in the Democratic Party and the real instability and fissures that result from attempting to construct a governing ideology out of identity politics and intersectionality.

While for now, Bernie Sanders has been obliged by his own political vulnerabilities in the Democratic primary around race and identity issues to support Omar, it is also clear that intersectionality is not his kind of politics and that he is seeking to rebuild the party’s message along a more class-based populist position that champions universal uplift, refashioning the party along social democratic lines and restoring the classic left-right divide in bourgeois politics in the hopes of building a more durable electoral coalition.

Nevertheless, given the depth of the cleavages in the party today, it is not clear if this vision is the right message to make it through a Democratic primary. Sanders has already been attacked for being “insensitive on race.” As a result of these attacks, he risks overcorrecting — delving into racial disparity discourse, championing his new campaign’s diversity and inclusion, etc. — diluting the universal message that would appeal to the blue collar whites he needs to win in the general election.

However, Sanders problems come not only from the cynical deployment of identity politics against him by the Democratic establishment. Many of Bernie’s most die hard “millennial socialist” supporters are also the most committed to identity politics and intersectionality. Bernie thus must placate this section of his base in the primary, hoping to pivot to more universalist and economic populist themes in the general election. Whether or not this will prove a successful strategy is unclear, but we can say is that it is unlikely that any Democratic candidate who might win the Presidency in 2020 will have the kind of New Deal electoral coalition at their back, that FDR once did. The tensions and the fractures within the neo-liberal body politic run too deep.

What this episode of supposed anti-Semitism in the Democratic Party really shows us is that there are no pure figures, no saintly candidates and no especially virtuous group identities in bourgeois politics. As capitalist society more and more devolves into competing identitarian claims as a result of its inability to offer a truly universal human perspective, it more and more attempts to trap us in a pointless and fruitless exercise of ranking the importance and virtuousness of various group claims among the multiple injuries inflicted upon the entirety of humanity by capital on a daily basis.

Attempts to render capitalist society more palatable by making it more “inclusive” or “diverse,” or by granting recognition to supposedly oppressed group identities, are illusory and self-defeating. In a world that is being sliced by bourgeois ideology into ever thinner slices of humanity defined by more and more particular and stylized identities, no level of inclusion is ever inclusive enough; every act of inclusion is by nature also an act of exclusion.[14] No amount of diversity will ever be definitive. For every group that achieves inclusions in the name of diversity, another will emerge to yell, “But what about our claims?!”[15]

Only a working class that is uncompromisingly putting forward the defense of its living and working conditions can overcome the divisions forced onto us by bourgeois politics and offer a way out of this morass. A genuinely proletarian movement will necessarily include the struggle against all forms of oppression and prejudice, because the proletariat, as Marx put it, is “an estate which is the dissolution of all estates, a sphere which has a universal character by its universal suffering and claims no particular right because no particular wrong, but wrong generally, is perpetuated against it”[16]. In sum, the working class will overcome the manifold divisions within its ranks because it will need to understand them both as obstacles to its immediate struggle, which must tend towards increasing unification, and as barriers to the conquest of real freedom, defined as the ability to achieve our individual potential in a world that has finally become humanized.

--Henk

03/14/2019

[2] For the details of the tweetstorm see here: https://www.politico.com/story/2019/02/10/ilhan-omar-israel-aipac-money-... [3]

[3] For the video of these comments see here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HnRC6gFrUao [4]

[6] In framing support of Israel as a matter of “dual loyalties,” Omar and Tlaib reveal their own will to power to act as judges of what constitutes real loyalty to the US state, not to mention effectively calling into question the patriotism of all those with dual or multiple citizenships, an increasingly prevalent phenomenon in a globalized world characterized by mobility and migration, which the bourgeois left generally celebrates. Previously, denunciation of the loyalties of dual citizens had been the province of the “right-wing,” such as Fox News host Tucker Carlson.

[7] The hypnosis trope appears to reflect a certain idiom Omar learned somewhere. While this is not enough to pass definitive judgment on her intentions, it certainly raises questions about her influences. In any event, most Democrats’ and leftists have little problem finding something racist even in Trump’s more subtle comments, but when it came to addressing one of their own’s questionable use of tropes, many preferred to circle the wagons.

[8] Conversely it may be the case that in Eastern Europe, anti-Semitism is currently more a feature of the populist right, but its clear that neither side of the traditional division of bourgeois politics has a monopoly on it. See for example the Pittsburgh Synagogue shooting, in which the perpetrator appears to have been motivated by right-wing conspiracy theory around George Soros’s activism in pushing global migration.

[9] See for example: https://en.internationalism.org/icconline/201605/13931/labour-left-and-jewish-problem [7]; https://en.internationalism.org/icconline/201805/15151/difficulties-bourgeoisie-s-political-apparatus [8]

[10] Ruy Teixeira and Jonathan Judis, The Emerging Democratic Majority (New York: Scribner) 2002. More recently, Judis had moved away from the conclusions of the book suggesting that Hispanic immigrants will likely come to see themselves as “white” and therefore will no longer be fiercely loyal Democrats. See: Redoing the Electoral Math, in the 09/14/2017 The New Republic, https://newrepublic.com/article/144547/redoing-electoral-math-argued-demographics-favored-democrats-wrong [9]. Conservative commentator Reiham Salam complements Judis’ new conclusions, suggesting that second generation Hispanic immigrants will develop their own populist tendencies, faced with competition from even cheaper imported labor from Africa and South Asia, See: https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2018/09/the-next-populist-r... [10]

[11] For a recent critique of “victimhood chic,” in which one’s status as a victim has itself become a form of privilege today, see John McWhorter’s analysis of the politics surrounding the Jussie Smollett hate crime hoax here: https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2019/02/jussie-smollett-story-... [11]

[13] In another illustration of the tensions within the Democratic collation, Omar was elected from a district (Minnesota-5) that while it has a sizable Somali-American refugee community is nevertheless majority white and has its own Jewish community. During her campaign for office Omar supposedly told local Jewish community groups that she did not support BDS, only to change her mind once winning the election. It is likely that in the interests of anti-Trump intersectional coalition-building, many Jews in the district voted for her. However, there are now rumblings of a possible primary challenge against Omar in 2020. But, for this to have any chance of succeeding, Democrats would have to find the right candidate to run against her—one with intersectional credentials of their own, lest accusations of Islamophobia sink the challengers’ campaign. One name that has been mentioned is Andrea Jenkins, a transgender African-American woman who currently sits on the Minneapolis city council. See: https://thehill.com/homenews/campaign/433970-democrats-upset-over-omar-s... [13]

[14] For example, the increasing availability of Spanish language services in the public sphere in the United States does nothing for those who speak Portuguese—except that for reasons of geographic and linguistic proximity they might also speak some Spanish and therefore they can struggle to get services in a language that is not quite their own and which has, in the terms of identity politics, itself become “hegemonic” in relationship to their Lusophonic identity. Interestingly, the issue of language hegemony and inclusivity is not something entirely foreign to the workers’ movement, as prior debates over Esperanto demonstrate.

[15] In fact, it may be the case that these kinds of “What about us?” claims lie at the heart of the so-called “white identity politics” that appeal to Trump voters. In a culture that increasingly gives recognition and assigns public virtue to the claims of groups with all sorts of hyphenated identities, the populist rallying cry of “What about regular/real/true American citizens?” expresses something meaningful to those with no other politically marketable identity to deploy and no particular group grievance to claim.

[16] “Introduction to the Critique of Hegel’s Philosophy of Right”, 1843

Rubric:

No solution to the ecological catastrophe without the emancipation of labour from capitalist exploitation

- 539 reads

The overwhelming consensus of serious scientific opinion is that we are already entering a global ecological catastrophe of unprecedented proportions. This is not the place to itemise all the various aspects of the disaster facing humanity, from the pollution of the sea, air and rivers to the impending extinction of innumerable of plant and animal species, culminating in the threats posed by the accelerating process of global warming. Suffice it to say that the combination of all these tendencies, if unchecked, could make the planet itself uninhabitable, and at the very least unfit to sustain a decent human existence.

It is our contention, however, that it is not enough to examine this problem through the lens of ecology, or the natural sciences, alone. To understand the underlying causes of ecological devastation, and the possibility of reversing it, we have to understand their connection to the existing social relations, to the economic system that governs the earth: capitalism. And for us that means using the only really scientific approach to understanding the structure and dynamics of human society – the method of marxism. One excellent point of departure here is Engels’ 1876 essay ‘The part played by labour in the transition from ape to man’, an unfinished movement that has been included within a broader unfinished symphony, The Dialectics of Nature[1].

Engels’ essay is an application of the understanding that only by looking at the human past from the standpoint of a class of labour – and of associated labour in particular – does it become possible to understand the emergence of the human species. Contrary to the mechanistic view that it is the result of the development of the human brain seen in isolation – its growth in size and complexity as the simple result of random mutations – Engels argues that in the final analysis man makes himself; that it is the dialectical interaction between hand and brain in the collective production of tools and the transformation of our natural surroundings which determines the “mechanical” capacities of the brain, the dexterity of the human hand, and the evolution of a specifically human consciousness. This consciousness is one in which planned, purposeful activity and cultural transmission outweighs the more instinctual actions of previous animal species.

“It goes without saying that it would not occur to us to dispute the ability of animals to act in a planned, premeditated fashion. On the contrary, a planned mode of action exists in embryo wherever protoplasm, living albumen, exists and reacts, that is, carries out definite, even if extremely simple, movements as a result of definite external stimuli. Such reaction takes place even where there is yet no cell at all, far less a nerve cell. There is something of the planned action in the way insect-eating plants capture their prey, although they do it quite unconsciously. In animals the capacity for conscious, planned action is proportional to the development of the nervous system, and among mammals it attains a fairly high level… But all the planned action of all animals has never succeeded in impressing the stamp of their will upon the earth. That was left for man[2].

In short, the animal merely uses its environment, and brings about changes in it simply by its presence; man by his changes makes it serve his ends, masters it. This is the final, essential distinction between man and other animals, and once again it is labour that brings about this distinction”.

There is no question that humanity acquired these capacities through collective activity, through association. In particular Engels argues that the evolution of language – a prerequisite for the development of thought and of cultural transmission from one generation to the next – can only be understood in the context of a developing social connection:

“It has already been noted that our simian ancestors were gregarious; it is obviously impossible to seek the derivation of man, the most social of all animals, from non-gregarious immediate ancestors. Mastery over nature began with the development of the hand, with labour, and widened man’s horizon at every new advance. He was continually discovering new, hitherto unknown properties in natural objects. On the other hand, the development of labour necessarily helped to bring the members of society closer together by increasing cases of mutual support and joint activity, and by making clear the advantage of this joint activity to each individual. In short, men in the making arrived at the point where they had something to say to each other. Necessity created the organ; the undeveloped larynx of the ape was slowly but surely transformed by modulation to produce constantly more developed modulation, and the organs of the mouth gradually learned to pronounce one articulate sound after another”.

The human capacity to transform nature has brought it enormous evolutionary and historical advantages, undeniably making humanity the dominant species on the planet. From the utilisation of fire to the domestication of animals and the sowing of crops; from the construction of the first cities to the development of vast networks of production and communication that could unify the entire planet: these were the necessary stages towards the emergence of a global human community founded on the realisation of the creative potential of all its members, in other words, of the communist future which Marx and Engels predicted and fought for.

A warning against arrogant assumptions

And yet The Part Played by Labour is anything but an arrogant hymn to human superiority. In the footsteps of Darwin, it begins by recognizing that everything that is uniquely human also has its roots in the abilities of our animal ancestors. And above all, no sooner has Engels noted the fundamental distinction between man and animal than he issues a warning which has a very clear resonance in the face of today’s ecological crisis:

“Let us not, however, flatter ourselves overmuch on account of our human victories over nature. For each such victory nature takes its revenge on us. Each victory, it is true, in the first place brings about the results we expected, but in the second and third places it has quite different, unforeseen effects which only too often cancel the first. The people who, in Mesopotamia, Greece, Asia Minor and elsewhere, destroyed the forests to obtain cultivable land, never dreamed that by removing along with the forests the collecting centres and reservoirs of moisture they were laying the basis for the present forlorn state of those countries. When the Italians of the Alps used up the pine forests on the southern slopes, so carefully cherished on the northern slopes, they had no inkling that by doing so they were cutting at the roots of the dairy industry in their region; they had still less inkling that they were thereby depriving their mountain springs of water for the greater part of the year, and making it possible for them to pour still more furious torrents on the plains during the rainy seasons. Those who spread the potato in Europe were not aware that with these farinaceous tubers they were at the same time spreading scrofula. Thus at every step we are reminded that we by no means rule over nature like a conqueror over a foreign people, like someone standing outside nature – but that we, with flesh, blood and brain, belong to nature, and exist in its midst, and that all our mastery of it consists in the fact that we have the advantage over all other creatures of being able to learn its laws and apply them correctly”.

In this passage, Engels provides us with a concrete example of the marxist theory of alienation, which is predicated on the recognition that, in given social conditions, the product of man’s own labour can become a hostile power, an alien force that eludes his control and acts against him. Without entering into a discussion into the more remote origins of this human self-estrangement, we can say with certainty that the qualitative development of this process is linked to the emergence of class exploitation, in which, by definition, those who labour are compelled to produce not for themselves but for a class that holds the power and wealth of society in its hands. And it is no accident that the development of exploitation and of alienated labour is connected to mankind’s progressive alienation from nature. The examples of “unforeseen consequences” of production that Engels provides us with in the passage just cited are taken mainly from pre-capitalist forms of class society, and it is precisely with these earlier forms of civilisation that we find the first clear example of man-made environmental disasters.

“The first cases of extensive ecological destruction coincide with the early city states; there is considerable evidence that the very process of deforestation which allowed civilisations such as the Sumerian, the Babylonian, the Sinhalese and others to develop a large-scale agricultural base also, in the longer term, played a considerable role in their decline and disappearance”[3].

But these were, relatively speaking, local catastrophes. In contrast to previous modes of production, capitalism is compelled by its deepest inner drive to dominate the entire planet. As it says in the Communist Manifesto,

“The need of a constantly expanding market for its products chases the bourgeoisie over the entire surface of the globe. It must nestle everywhere, settle everywhere, establish connexions everywhere…

The bourgeoisie, by the rapid improvement of all instruments of production, by the immensely facilitated means of communication, draws all, even the most barbarian, nations into civilisation. The cheap prices of commodities are the heavy artillery with which it batters down all Chinese walls, with which it forces the barbarians’ intensely obstinate hatred of foreigners to capitulate. It compels all nations, on pain of extinction, to adopt the bourgeois mode of production; it compels them to introduce what it calls civilisation into their midst, i.e., to become bourgeois themselves. In one word, it creates a world after its own image”.

This necessity to “globalise” itself, however, has also meant the globalisation of ecological catastrophe. For Marx, the capitalist social relation marked the high point of in the whole process of alienation, because now the exploitation of human labour is no longer geared towards a personal relation between master and servant, as it was in previous class societies, but towards the expansion and growth of a fundamentally impersonal power – “Das Kapital”, or the profit system. The universal advent of production for the market and for profit means that the tendency for the results of production to escape the control of the producer has reached its ultimate point; moreover, the capitalist exploiter himself, though benefiting from the proceeds of exploitation, is also driven by the remorseless competition for profits, and is, in the final analysis, merely the personification of capital. We are thus confronted with a mode of production which is like a juggernaut that is running out of control and threatening to crush exploiter and exploited alike.

Because capitalism is driven by the remorseless demands of accumulation (what it calls “economic growth”), it can never arrive at a rational, global control of the productive process, geared to the long-term interests of humanity. This is above all true in a period of economic crisis, where the pressure to penetrate the last untouched regions of the planet and ransack their resources becomes increasingly irresistible to all the feverishly competing capitalist and national units.

The extreme point in the alienation of the worker in the process of production is thus mirrored in the most extreme alienation of humanity from nature. In the same way that the workers’ labour power is commodified, our most intimate needs and feelings seen as potential markets, so capitalism sees nature as a vast warehouse that can be robbed and ransacked at will in order to fuel the juggernaut of accumulation. We are now seeing the ultimate consequences of the illusion of ruling over nature “like a conqueror over a foreign people”: it can only lead to “nature taking its revenge...” on a scale far greater than in any previous civilisation, since this “revenge” could culminate in the extinction of humanity itself.

“Taking back control”

Let’s return to the last passage from Engels, where he writes that “all our mastery of (nature) consists in the fact that we have the advantage over all other creatures of being able to learn its laws and apply them correctly”. He goes on thus: “And, in fact, with every day that passes we are acquiring a better understanding of these laws and getting to perceive both the more immediate and the more remote consequences of our interference with the traditional course of nature. In particular, after the mighty advances made by the natural sciences in the present century, we are more than ever in a position to realise, and hence to control, also the more remote natural consequences of at least our day-to-day production activities”.

The paradox of capital is that while the development of science under its reign has allowed us to understand the laws of nature to an unprecedented degree, we seem increasingly powerless to “apply them correctly”.

For Engels, of course, the capacity to control the consequences of our production depended on the overthrow of capitalism and the appropriation of science by the revolutionary working class. But Engels, confident that the victory of the socialist revolution was not far off, could not have foreseen the tragedy of the centuries that followed his: the defeat of the first attempt at world proletarian revolution, and the prolongation of the capitalist system that has reached such a level of decay that it is undermining the very bases for a future communist society. In the nightmare world that decadent capitalism is shaping before our eyes, scientific knowledge of the laws of nature, which could and should be used for the benefit of humanity, is more and more being enlisted to aggravate the mounting calamity, by bending it to the intensification of the exploitation of man and nature, or the creation of terrifying weapons of destruction which themselves pose a major ecological threat. Indeed, a measure of capitalism’s decadence is precisely this growing gap between the potential created by the development of the productive forces – of which science is a vital part – and the way this potential is blocked and distorted by the existing social relations.

On its own even the most disinterested scientific knowledge is powerless to turn back the tide of environmental despoliation. Hence the endless warnings of concerned scientific bodies about the melting of the glaciers, the poisoning of the oceans or the extinction of species are endlessly ignored or counteracted by the real policies of capitalist governments whose first rule is always “expand or die”, whether or not these governments are ruled by crude climate change deniers like Trump or by earnest liberals and self-proclaimed socialists.

The solution to the ecological crisis – which, increasingly cannot be separated from capitalism’s irreversible economic crisis and its drive towards imperialist war – can only come about if mankind “takes back control” through the suppression of capital accumulation, with all its outward expressions, not least money, the state, and all national frontiers. Labour must emancipate itself from capitalist exploitation: the entire process of production must be organised on the basis of the needs of the producers and their long-term interaction with the rest of nature.

This is a precondition for the survival of our species. But it is also much more than that. In the last-cited passage, Engels continues: “the more this progresses the more will men not only feel but also know their oneness with nature, and the more impossible will become the senseless and unnatural idea of a contrast between mind and matter, man and nature, soul and body, such as arose after the decline of classical antiquity in Europe and obtained its highest elaboration in Christianity”.

Here Engels returns to some of the most audacious hypotheses of the young Marx about the nature of communism. Fully realised communism means the emancipation of labour not only in the sense of getting rid of class exploitation: it also demands the transformation of labour from a penance into a pleasure, the unleashing of human creativity. And this in turn is the precondition for the subjective transformation of the human species, which will “feel and know” its oneness with nature.

Such notions take us into a far-distant future. But it will only be our future if the class which embodies it, the world proletariat, is able to fight for its specific interests, to rediscover its sense of itself as a class, and to formulate a perspective for its struggles. This will mean that its immediate, defensive struggles will more and more have to incorporate the struggle against capitalist oppression and barbarism in all their forms; at the same time, it is only by fighting on its own class terrain that the proletariat can draw behind it all those layers of society who want to call a halt to capitalism’s cannibalisation of nature. The recognition that capitalism is a threat to all life on the planet will be central to this broadening of the class struggle towards a political and social revolution.

Amos

[2] Anthropologists, geologists and other scientists have coined the term “Anthropocene” to designate a new geological era in which man has definitely stamped his will upon the atmosphere, climate and biology of the Earth. They put forward different moments to mark this transition from the Holocene to the Anthropocene, some seeing the invention of agriculture as crucial, while others opting for the beginning of the industrial revolution, i.e. the beginning of the capitalist epoch, but also including a phase of considerable acceleration after 1945.

[3] “Capitalism is poisoning the Earth”, https://en.internationalism.org/ir/63_pollution [16]

Rubric:

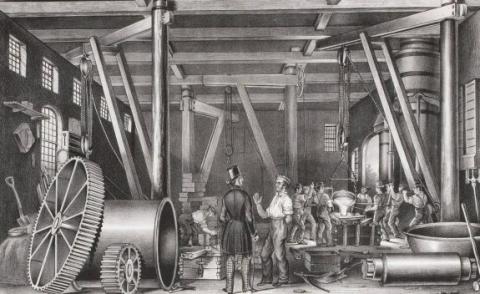

Notes on the early class struggle in America: Part 3 - The birth of the US workers’ movement and the difficult struggle for class unity

- 316 reads

“...Social relations are no longer the same as when the Republic was founded. The introduction and development of large-scale industry have produced a new revolution, dissolved the old classes, and above all, created our class, the class of propertyless workers. New relations require new institutions.” (Preamble to the demands of the American Workers’ League, 1853) [1]

Introduction

In the first part of this occasional series we looked at the birth of the proletariat in North America and its earliest struggles, showing how black chattel slavery was introduced to keep black and white workers divided along racial lines.[2]

The second part exposed myths surrounding the birth of democracy in America, showing that by successfully harnessing the struggles of white workers to the creation of a separate state, the Revolution of 1776 strengthened capitalist domination in North America and entrenched black slavery while deploying racist ideologies to ensure the working class remained divided.[3]

In the third and final part of the series we will look at the first attempts by the US working class to organise itself into trade unions and political parties and the first mass struggles of the early workers’ movement against American capital. These deserve to be better known today if only because they highlight the vanguard role played by the American working class as a fraction of the world proletariat at this time.

But we also need to understand the extremely difficult conditions imposed on the American working class by the development of capitalism in the USA, where a highly intelligent and flexible ruling class actively prevented the building of solidarity by reinforcing divisions between white and black, ‘free’ workers and slaves, immigrant and ‘native-born’ workers – divisions that still weigh heavily on the struggle for class unity today.

The struggle to organise against American capital

For all the noble phrases of the Declaration of Independence and Bill of Rights, workers in the new republic had no right to organise or defend themselves. The new ruling class did not hesitate to use the democratic state to enforce colonial-era laws which treated strikes and trade unions as criminal conspiracies; corporal punishment, the whipping post and branding by the state were all perfectly legal, not only for black slaves but also for ‘free’ men, women and children. Strikes by women workers were called ‘mutinies’…

But workers had no choice but to defend themselves against such a rapacious capitalist class. The earliest struggles of American workers tended to unify around the demand for a shorter working day which was seen by the most politically advanced workers as vital to enable the development of class consciousness. In 1827 unions in Philadelphia formed the city-wide Mechanics’ Union of Trade Associations in order to build solidarity between trades and fight for political reforms. This led to the formation of the Working Men’s Party (1828), the first independent working class party in the world. For the party’s leaders –.men like William Heighton[4] – the trade union struggle to raise wages and shorten hours was not enough, because “All our legislators and rulers are nominated by the accumulating classes and controlled by their opinions - how then can we expect that laws will be framed which will favour our interest?”[5] It was therefore necessary to call on workers to elect their own representatives to enact the ten-hour day. The formation of working men’s parties in New York and Boston followed and by 1834 the movement had spread to 61 towns and cities.

This early political movement was led by skilled craft workers who found their role and status undermined by speed-ups, lower wages, longer hours and the use of unskilled labour. Having fought as the radical wing of the bourgeois national liberation struggle (see part two) these workers tended to identify with the republican ideology of the American Revolution (Paine, Jefferson et al); by demanding a shorter working day they considered they were seeking the ‘equal rights’ they were entitled to as American citizens. This undoubtedly showed illusions in the democratic state and its founding myth of a republic of ‘free men’, but by de-skilling previously independent craft workers and creating a growing class of wage labourers, capital itself revealed the contradiction between the supposedly “self-evident” truth that “all men are created equal” and the reality of industrial wage slavery – a contradiction the early workers’ movement did not hesitate to ruthlessly expose.

More significantly, the ‘workies’ drew on the ideas of the Ricardian and utopian socialists to develop a political strategy based on the argument that as the producers of all wealth in society workers should receive the full product of their labour. While it was utopian to believe that wage labour could, in effect, be voted out of existence through electing working class representatives, by demonstrating that the working class was the source of all wealth in society, these early American militants boldly ‘threw down the gauntlet to the theory of the capitalists’ (Marx) and challenged the political power of the American bourgeoisie.

The great mass of the American proletariat remained unorganised. Unskilled workers, women, children and freed slaves possessed few or no legal rights or representation and their attempts to defend themselves from ferocious exploitation were treated as dangerous acts of rebellion. Nevertheless, the struggles of these workers, often led by women and children, were among the most militant in this period, frequently leading the way and winning the solidarity of organised workers. On the canals and turnpikes, where an army of unskilled, often recent immigrant workers toiled in murderous conditions, there were hundreds of strikes and violent uprisings as well as acts of sabotage and resistance, reaching a peak in 1834-38. State militias were regularly called out to crush rebellions and shoot down workers; dozens were killed and hundreds arrested, a pattern repeated later in the construction of the railroads,[6] while in the new prison-like mills of New England, where workers – mostly women and children – toiled long hours for miserable wages in appalling conditions, resistance to the repressive regime was led by militant women workers. There was frequent solidarity between factory and skilled craft workers; in the first recorded strike by factory workers in 1828, for example, children supported by parents and local artisans in Paterson, New Jersey, struck over a proposed change in their dinner hour and won.[7] There were also early attempts to organise factory workers, with the formation in 1832 of the New England Association of Farmers, Mechanics and Other Workmen, which despite being unsuccessful played an important role in advancing the struggle of the early US workers’ movement for the shorter working day.[8]

The first great wave of workers’ struggles in the USA

From the beginning of the 1830s we can see a rising wave of workers’ struggles in the USA focused on the demand for a ten-hour day, reaching a high point in 1835 with the first general strike in working class history. The strike wave spread from Baltimore to Boston, with militant workers sending delegations to other cities and distributing a manifesto calling for solidarity, which had an ‘electric’ effect on the movement, extending it to Philadelphia where workers quickly shut down the city and held mass meetings to demand the ten-hour day and higher wages for both men and women. Faced with this demonstration of class solidarity employers were forced to concede most of the workers’ demands and when the news of the victory spread it provoked a renewed wave of strikes by factory and skilled workers across the eastern United States.

This wave of struggles showed a real strengthening of class solidarity, uniting skilled and unskilled, men and women, recent immigrants and native-born proletarians around the demand for a shorter working day, which was also reflected in the development of permanent organisations: membership of trade unions reached a peak of around 300,000 in 1836, a proportion of workers not matched until the New Deal 100 years later.[9] There were also initiatives to form national organisations; the National Trades’ Union formed in 1835 existed for three years. But the most significant development was undoubtedly the formation in more than a dozen cities of general unions to co-ordinate the struggles of skilled, unskilled and factory workers; there were probably the most advanced union organisations created by the working class up to this point in its history.

This growth of class solidarity also had an international dimension. The strike wave in the US can only be understood in the context of the whole wave of class struggles in Europe at this time and the 1830 July Revolution in France was a definite influence on American workers, who sent messages of solidarity to their Paris comrades: “Fellow laborers! We owe you our grateful thanks. And not we only, but the industrious classes – the people of every nation. In defending your rights, you have vindicated ours.”[10]

The development of capitalism and the strategy of capital to manage the class struggle

In this way, in the first three decades of the 19th century, the American working class, led by the skilled craft workers of the northern cities, formed one of the most advanced fractions of the world proletariat, creating its first political parties and city-wide general unions. This early US workers’ movement was militant, internationalist and, in the context of this phase of capitalist development, highly class conscious. One of its key strengths was its recognition of the importance of political action to secure permanent reforms alongside the trade union fight for immediate demands. But, led by the skilled craft workers, it was destined to be eclipsed by the development of capitalism itself and the rise of the industrial proletariat.

With the economic depression of 1837-44 this pioneering fraction was plunged into the depths of defeat. The organisations so painfully built up by the American workers were effectively wiped out and the capitalist class went onto the offensive. When workers’ struggles finally began to revive after 1844, it was in changed conditions due to the development of capitalism itself; in particular the rapid growth of capitalist methods of production based on manufacturing, which hastened the destruction of artisan and skilled craft roles and the emergence of a permanent class of wage labourers in the factories and port cities of the eastern seaboard. These changes were reflected in the strategy of capital to manage the class struggle.

The American working class fought for and won important gains in this period, including higher wages and a shorter working day – although these were paid for through increases in productivity – and the legal right to (peacefully) organise. Still, strikes remained illegal and unions were still considered an alien import into the US. The 1850s saw several waves of struggles by industrial workers culminating in the largest strike in the USA so far; the New England shoemakers’ strike of 1860 (“The Revolution in the North”). From 1844 onwards we see the organisation of the factory workers, with women playing a leading role.[11] This period also saw the growth of permanent organisations including renewed efforts to create city-wide and national unions – although these tended to be short-lived owing to the cycle of boom and ‘Panic’ (ie. financial crisis) which necessitated their rebuilding almost from scratch.

The capitalist class put up bitter resistance to a reduction in the working day and despite some extremely militant struggles – like that of women textile workers supported by men and boys in western Pennsylvania in 1845 – all attempts by the workers’ movement to organise a general strike to win this demand failed, forcing it to resort to exerting pressure on the institutions of the bourgeois state for legislative reform.

With the ‘take off’ of the American economy – by 1860 the USA was the fourth most powerful capitalist industrial nation in the world – the bourgeoisie was able to create a more flexible political apparatus and to grant limited reforms, at the same time diverting potentially threatening class struggles into safer political channels. The independent workers’ parties of the early 1830s rapidly declined and broke up, due partly to the deliberate attempts of the bourgeoisie to destroy them, but also to the success of the left-wing of the Democratic Party (‘Jacksonian Democracy’) in winning a base of support among white male workers and small farmers with policies specifically aimed at mobilising working class electoral support, combining the slogan of ‘equal rights’ for rich and poor and the use of anti-elitist, anti-monopolist rhetoric. As a result, political action by the working class tended to focus on pressuring the Democratic Party to adopt its demands by threatening to withdraw its support and run its own candidates for election. The response of the Democratic bourgeoisie to the Equal Rights Party or ‘Locofocos’, originally a protest against corruption in the New York party and conspiracy charges against striking workers, was to adopt many of its demands, combining reform of the banking and legal systems with an end to conspiracy laws..[12]

There were some significant attempts to create a working class party at this time, in particular by the German-speaking workers (who in some important industrial centres like St Louis were the dominant force in the workers’ movement). The American Workers’ League, formed in 1853 by 800 delegates at a mass meeting in Philadelphia, called on workers “without distinction of occupation, language, color, or sex” to organise into “a closely knit and independent political party”.[13] This met resistance from the narrow craft unions and proved short-lived, but, led by supporters of the ‘Marx party’ in the US, the League attempted to build links between German- and English-speaking workers and link struggles for economic and political demands, in this way laying down important principles for the construction of a future class party in the US.[14]

Reinforcing ethnic, religious and racial divisions in the working class

The biggest challenge to the building of class unity in this period – aside, of course, from the continued existence and growth of black slavery – was mass immigration. In one of the greatest migrations of labour in human history, between 1840 and 1860 4.6 million migrants arrived in the USA, mainly from Britain, Ireland and Germany.

For the working class, this brought a huge influx of fellow proletarians and allies: British workers brought their invaluable experience as pioneers of union organisations and of economic struggles; Irish workers brought their own traditions of violent resistance to landlords, while German workers, some former fighters from the 1848 revolutions, also formed a strong contingent in the trade unions and went on to found the first scientific socialist organisations in the USA.[15]

For the American ruling class, mass immigration brought not only a vital supply of labour but a weapon in its counter-offensive against the working class, to lower labour costs and put pressure on wages and conditions in order to prevent the growth of class solidarity. The fear and hostility of ‘native-born’ workers towards immigrants was carefully exploited by bourgeois propaganda and promoted by religious institutions like the Catholic Church and the two-party system, which mobilised native-born workers behind the Republican Party and Irish workers, for example, into the Democratic Party. Some sections of the working class joined in the pogromist campaigns whipped up against German, Irish and black workers, especially during the period of defeat in 1837-44 when mob attacks, lynchings and destruction of churches were common in the large eastern cities. In 1844, for example, there were violent battles between Protestant Irish native-born workers and Catholic Irish immigrants in Philadelphia which were only ended by militia firing cannons into the crowd.

Skilled craft workers facing the destruction of their role tended to combine a militant defence of working class interests with calls for restrictions on immigration.[16] But the sheer numbers of immigrants continuing to arrive made such a stance increasingly unrealistic, while the periodic economic crises of US capitalism tended to break down divisions, at least temporarily, in the face of mass unemployment; in the 1857 crisis, for example, there were mass meetings of German, Irish and American workers in New York to demand work and in Philadelphia a Central Workingmen’s Committee was formed uniting skilled and unskilled, American- and foreign-born workers to fight for unemployment relief.[17] Some unions actively worked to organise immigrant workers in their trades and combat anti-immigrant campaigns, warning that hostility towards immigrant workers was being deliberately used by employers to distract workers’ attention from class issues.

Above all solidarity was built through struggle. Common experience of industrialisation and repression tended to break down initial hostility and suspicion between groups of workers; impartially meted-out police brutality during an 1850 strike in New York helped to build solidarity between German and native-born American members of the Tailors’ Union, with German workers protesting against the imprisonment of their fellow workers.[18] The 1860 New England shoemakers’ strike – the most extensive struggle in the US before the Civil War – was also significant for uniting Irish immigrant and American-born workers, with militant women again taking a leading role.

It was precisely these tendencies for the struggles of the growing industrial proletariat to overcome ethnic, religious and sexual divisions that forced the bourgeoisie to deploy a strategy based on the racist concept of white supremacy. The reactionary idea that ‘whiteness’ entitled European workers to political rights and jobs was used to justify the systematic exclusion of ‘free’ black workers in the northern states from employment and basic democratic rights, turning them into scapegoats for the poverty of the poorest white workers and easy targets for pogroms. Despite initial support among Irish workers for the abolition of slavery, for example, this was presented with some success – primarily by the Democratic Party and the Catholic Church – as bringing the threat of a ‘flood’ of black labour. This led to so many examples of racial violence that black workers called the bricks hurled at them “Irish confetti”.[19]

The roots of these racial divisions were not simply economic. In fact Irish Catholic workers found themselves in competition for unskilled jobs not with black but other white European workers and their more recent immigrant compatriots. Irish and black workers often lived, worked and struggled side-by-side and were even joint targets of racist attacks (eg. in Boston 1829). But with the growth of Irish immigration, especially after the 1845-49 Great Famine, and the increasing importance of the Irish vote for the two main bourgeois parties, ruling class propaganda cynically manipulated the feelings of powerlessness and anger engendered by the experience of being torn from the land and surviving the horrors of hunger only to be thrown into the brutal world of wage labour, or lack of it, accompanied by the desperate poverty that was the introduction to capitalism in the USA for the poorest immigrants.

Conclusions

The US proletariat in this period faced immense difficulties imposed on it not just by the development of capitalism but the conscious strategy of a highly intelligent and flexible ruling class which understood the need for policies specifically designed to mobilise working class support while at the same time using violence and repression against militant struggles to divert workers’ energies into legal channels of reform. With no need to struggle against pro-feudal forces, the American bourgeoisie was free to use the two-party system to operate an effective division of labour against the working class, developing the Democratic Party as a specific means of diverting growing class struggles while at the same time reinforcing ethnic, religious, sexual and racial divisions in the working class.

Such a strategy was of course far from unique in ascendant capitalism; the most obvious example, dealt with extensively by Marx, was the antagonism between English and Irish workers, deliberately fostered by the capitalist class to force down wages and maintain its political power.[20] Divisions within the proletariat are inevitable in an exploiting system based on the wage labour relationship and competition between human beings; capitalism is above all a social relation between classes in which the ruling class, in order to maintain capitalist private property, must continually and consciously act to prevent the unification of the proletariat.

What was specific to the USA was the existence of black chattel slavery in such a large and potentially powerful capitalist economy. As a result, the industrial revolution in the US was shaped by the political rule of a slave-owning class whose plantation economy was essential to the survival of the capitalist regime installed by the American Revolution and by the racist ideologies developed to justify it, based on pseudo-scientific concepts of biological inferiority and white ‘Anglo-Saxon’ supremacy.[21]

What we see from the 1830s onwards is the development of such ideologies by the American capitalist class in response to the rapid and massive growth of a racially and ethnically heterogeneous industrial proletariat as part of a deliberate strategy to prevent the tendency towards class unity. The concept of white supremacy was – and remains today – deeply embedded in the apparatus of capitalist domination in the USA, as part of the means to control the development of class struggles.

For its own part, despite all these obstacles, and in circumstances definitely not of its own choosing, the American working class was ceaselessly confronted with the necessity to struggle to defend itself and for its forces to come together, to fight for its unity, which required a struggle against all the forces that sought to divide it. For the US proletariat black slavery was thus not only a moral outrage but a practical obstacle to its unification and for this reason, despite the real gains made, in this historic period it was impossible to separate the difficult struggle for class unity from the struggle against black slavery.

We will return to this question in a future article.

MH

NB: This article was revised on April 16 to include the author's latest version.

[3] ‘The birth of American democracy: “Tyranny is tyranny”’, https://en.internationalism.org/icconline/201402/9461/birth-american-dem... [19]

[4] William Heighton was an immigrant English shoemaker, influenced by the ideas of the Ricardian and ‘primitive’ socialists. He played a key role in organising the Mechanics’ Union of Trade Associations, founded and edited the Mechanic’s Free Press (probably the first workers’ paper in the US), and became leader of the Philadelphia Working Man's Party.

[8] A key role in the Association was played by Seth Luther, a carpenter, whose widely-read Address to the Workingmen of New England (1832) was a powerful denunciation of conditions in the cotton mills. A talented speaker and organiser, Luther was very active in the early trade union movement and the struggle for the ten-hour day, including moves to form a national union.

[13] See American Workers’ League Wikipedia entry and Karl Obermann, Op. Cit., p.35.

[16] For example, the Address to the Working Men of New England by Seth Luther (1833) ended by insisting on the right of Congress to protect them from the “importation of foreign mechanics and laborers, to cut down wages of our own citizens”.

[19] David Roediger, The Wages of Whiteness: Race and the making of the American working class, 1991, p.136.

[20] See for example Marx to S. Meyer and A. Vogt, 9 April 1870, https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1870/letters/70_04_09.htm [21]

[21] The highly ideological nature of such concepts is underlined by Benjamin Franklin’s exclusion from the so-called ‘white race’ not only of “swarthy” Spaniards, Italians, French, Russians and Swedes but all Germans except for Saxons… (Observations concerning the increase of mankind, etc., 1751)

Rubric:

The fire at Notre-Dame de Paris: capitalism is incapable of preserving the heritage of humanity!

- 357 reads