World Revolution 2019

- 438 reads

Brexit Crisis: Ruling class divisions won’t help the working class

- 322 reads

The British ruling class is in a mess over Brexit. Two and a half months before the March 29 deadline, parliament finally had its ‘meaningful’ vote on the Withdrawal Agreement, which lost by a record 230 votes. It’s not just parliament that is divided on the question, so are both the Tory and Labour parties. Parliament is vying for more government powers (eg Speaker Bercow allowing an amendment to insist the PM comes back to parliament with plans 3 days after losing the vote, when it is not allowed in the normal rules); Jacob Rees-Mogg has proposed parliament should be suspended. 2 months before Brexit is due businesses are complaining about the uncertainty of what will happen and particularly if the country crashes out of the EU with no deal.

How could such a thing occur in a previously stable bourgeoisie with a reputation for control of its political apparatus? For The Economist “The crisis in which Britain finds itself in large part reflects the problems and contradictions within the idea of Brexit itself” (19.1.19). But this hardly explains why it has exposed itself to these problems and contradictions, why the Cameron government, which despite the divisions in the Tory party was firmly in favour of remaining in the EU, should hold an in/out referendum and both main parties promised to honour the result. Something has changed since the Major government was plagued by the Eurosceptic “bastards” making things difficult but never able to fundamentally change the policy of remaining in the EU. Since then we have seen the growth of right wing populism on an international scale with its strongly nationalist, anti-immigration and “anti-elitist” ideology. These are all clearly bourgeois themes that have been used by governments of left as well as right (such as the Blair government’s condemnation of “bogus” asylum seekers and May’s infamous “hostile environment” for immigrants) but the populist forces are irrational and disruptive as we see with the current Italian populist government, the Trump presidency and Brexit. In France populism has heavily influenced the Yellow Vest protests. Populism has taken the form of Brexit and UKIP in Britain, and found a substantial echo in the Tory and Labour parties, because of the divisions that had already opened up during the UK’s decline from a global imperialism to a second rate imperialist power over the last hundred years (see ‘Report on the British situation’ pages 4 and 5). If the ruling class is heading for the Scylla of Brexit it is above all because of its efforts to avoid the Charybdis of populism.

Ruling class forced onto rocks of Brexit by populist tide

Everyone can criticise May’s Withdrawal Agreement. Brexiters don’t like it aligning UK regulations to the EU to avoid a hard Irish border – some of them would be happy with no deal; Corbyn wants it to do the impossible, keep in a customs union with the EU while also avoiding the free movement of labour; some Remainers want to have a new “people’s vote” in the hope of overturning Brexit. Yvette Cooper is calling for a delay so government and parliament can agree a deal. Some of the hard Brexiters such as Rees-Mogg have been making noises about possibly supporting a new deal. But unless it crashes out with no deal the final settlement is not up to Britain, but the 27 EU countries.

Uncertainty reigns throughout the bourgeoisie. Businesses want certainty so they can prepare. NHS departments are discussing how they will manage the supply of medication. The CBI is warning a no deal Brexit would lead to an 8% loss in GDP, and its director general, C Fairbairn, said “At my meetings at Davos there is a recognition that the causes of vulnerability of the global economy now include Brexit” (Guardian 24.1.19). She went on to note that it is leading to a questioning of the UK’s global brand, and emphasised the need to rule out no deal to protect investment and jobs. Businesses, including the NHS, need the post-Brexit immigration model to continue to allow the immigration of workers from the EU earning less than £30,000.

The importance of keeping the Irish border open, insisted on by the EU, which is causing so much consternation to Brexiters who don’t want to be aligned to EU rules, is one of the pillars of the Good Friday Agreement. Since power sharing has broken down for months as the DUP and Sinn Fein cannot agree, the border is what remains in operation. As if on cue to remind everyone what is at stake, the New IRA set off a car bomb outside a court in Derry on 19 January.

The problem of Brexit is widening divisions in both the Tory and Labour parties. If the strong Brexiter wing among conservatives is obvious, we should not forget that in 2016 there was a vote of no confidence in Jeremy Corbyn by the parliamentary LP because he was such a reluctant Remainer, and was widely blamed for the referendum result. The divisions in the LP were widely thought to threaten its unity in 2016 and the 2017 election only reconciled the PLP to put up with Corbyn temporarily. The difficulties in the LP should not surprise us when we look at what is happening across Europe with the Socialist Parties in France and Spain being largely eclipsed by France Insoumise and Podemos respectively. Nor when we see the poor showing of the German SP after years in a grand coalition with Angela Merkel.

One of the reasons Theresa May has consistently given for ruling out a second referendum, despite the impasse of the Brexit deal, the weakening of the UK’s economy and standing in the world, and the likelihood of a change of opinion, is essentially the fear that it would stir up a loss of confidence in democracy and thus open the door to a populist-influenced social unrest.

Divisions used against the working class

While the government is more immediately afraid of populism, it is the “executive organ” of a capitalist class that can never forget the threat posed by the working class. We saw this when the PLP was temporarily reconciled to Jeremy Corbyn after the better than expected election result, showing he could mobilise a number of young proletarians who were previously disaffected with politics. It is shown by Theresa May, after losing the vote on the Brexit agreement, being at pains to try to meet all important political figures to discuss the next steps, including TUC general secretary Frances O’Grady and leaders of Unite, GMB and Unison. Not that the unions speak for the working class – they don’t. They play the role of understanding the mood of the workers, just how far they can be pushed in the imposition of austerity and lay-offs before they react, and of keeping any struggles within safe legal boundaries. The fact that they have been consulted, and that May was so keen to emphasise the need to keep workers’ rights, is evidence that the bourgeoisie has not forgotten about its gravedigger, in spite of its more immediate concern with populism.

It would be a great mistake, however, to think that the disarray in the ruling class in the face of populism is helpful to the working class. Right now there is a historically low level of strikes and the proletariat is finding it very difficult even to recognise itself as a class. It risks falling for and being divided along the lines of the various ideologies put forward by the ruling class. None of these ideologies, for Brexit or Remain, for referendums or parliament, have anything to offer the working class. Whichever way Brexit goes, the world economic crisis will continue to deepen, and in response all factions of the bourgeoisie will be obliged to press ahead with austerity and new attacks – and they will no doubt be blamed on the referendum result even if very similar attacks are being imposed on workers elsewhere, either inside or outside the EU.

For the workers to resist attacks they must unite and struggle together. Capital can only divide us: Brexiteer against Remainer; ‘white working class’ in the North against more ‘cosmopolitan’ workers in London; old against young who have to live with the consequences of the vote; ‘native’ against immigrant. Let us not forget that both Labour and Tory parties are in favour of limiting immigration to those needed by capital, and both are quite capable of blaming lack of health services and schools on the newcomers after running them down for decades. Above all we must not be caught up in campaigns for or against populism.

The danger of being caught up in populism is evident in its open nationalism and obvious will to divide workers between ‘native’ and immigrant – for example UKIP’s poster showing immigrants in Europe to frighten people into voting Leave. Internationally we can see the same themes from AfD in Germany, Trump with his wall and “bad hombres” in the USA, the refusal of immigrants in Italy. We see the same themes in the Yellow Vest protests that started in France, a “popular revolt” that actually undermines the ability of workers to struggle: “This ‘popular revolt’ of all the ‘poor’ of ‘working France’ who can’t ‘make ends meet’ is not as such a proletarian movement, despite its sociological composition. The great majority of the ‘gilet jaunes’ are workers, paid, exploited and precarious with some not even affected by the SMIC (minimum wage), without counting the retired who don’t have the right to the minimum pension. Living in isolated urban or rural areas, without public transport to get to work or children to school, these poor workers need a car and they are thus the first to be hit by the increase in petrol taxes and new technical requirements for their vehicles…

The explosion of the perfectly legitimate anger of the ‘gilet jaunes’ against the misery of their living conditions has been drowned in an inter-classist conglomeration of so-called free individual-citizens. The rejection of ‘elites’ and politics in general makes them particularly vulnerable to the most reactionary ideologies, notably extreme-right xenophobia. The history of the twentieth century has largely demonstrated that it is the ‘intermediate’ social layers (between proletariat and bourgeoisie), notably the petty-bourgeoisie who make the bed for the fascist and Nazi regimes (with the support of bands of hateful and vengeful lumpens, blinded by prejudice and superstitions which hark back to the dawn of time).” (https://en.internationalism.org/content/16621/police-violence-riots-urba... [1]).

The divisiveness of populism does not mean we should fall for anti-populism, with its illusions in liberal democracy, or the Labour Party, which has also attacked the working class every time it has been in government (yes, even the Atlee government which brought in the NHS) and restricted immigration when capital did not need such an expanding workforce. We must not be drawn in to supporting one ideological cover for the capitalist state over another. Above all we must reject the idea of blaming a section of the working class for populism. We have to remember that whether unemployed in a rundown industrial area, on zero hours for one of the new internet businesses, struggling with student debt, or worried about living on a declining pension, we are all part of the same class, and the capitalist state and all its political forces are our enemy. Alex 26.1.19

Rubric:

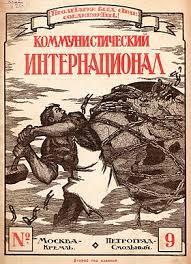

Lenin, Luxemburg, Liebknecht

- 335 reads

100 years after the assassination of Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Liebknecht by the Social Democratic government of Noske and Scheidemann, we are reproducing an article which appeared in no. 10 of L’Étincelle, organ of the Gauche Communiste de France, in the year 1946.

L’Étincelle first appeared in the midst of the imperialist butchery of the Second World War. It was an illegal paper, sold from hand to hand in the utmost clandestinity. At the risk of their lives, the militants of the GCF fought against a war which in the name of ‘ant-fascism’ and the ‘defence of the Socialist Fatherland’ was driving the workers to massacre each other in the interests of imperialist capital. They braved the ever-present danger of state repression, whether from the Vichy government or the Gestapo. But the greatest danger they faced came from a party which dared – and still dares – to call itself ‘Communist’, a party which broke all records in propagating the most shameless chauvinism. In the name of Lenin, of the workers’ revolution, this ‘Communist’ Party openly called for pogroms, for the physical liquidation of individuals who stood against the dupery of anti-fascism. It will always be remembered for its infamous slogan at the time of the ‘Liberation’: “a chacun son Boche” – each to his own Hun.

The Social Democrats who, in 1914, became the recruiting sergeants of the imperialist war, and, in 1919, the bloodhounds of the counter-revolution, were ably succeeded and even surpassed by the Stalinist CPs of the 30s and 40s. By invoking the revolutionary leaders who, in 1914-19, remained loyal to the internationalist principles of the working class, L’Étincelle was itself raising high the flag of proletarian internationalism against those who, in its own day, continued to trample it into the mud. And since in its every battle the proletariat is still forced to confront the descendants of these traitors, Social Democrat or Stalinist, the message in this article has lost none of its urgency for today.

ICC

Revolutionaries are commemorating the anniversary of the death of these three militants and leaders of the international proletariat at a particularly agonising moment, when the working class in all countries has been plunged into the blackest misery: when humanity has only just come out of six years of the most atrocious butchery; when all the capitalist states are feverishly preparing for a third world war; when the weak class reactions of the proletariat have been inexorably and preventively crushed by the monstrous military forces of capital, or have been derailed, deformed and diverted thanks to the so-called ‘workers’ parties’, which are in the service of capitalism. To evoke these three figures, their lives, their work, their struggle, is to evoke the history and experience of the international struggle of the proletariat in the first quarter of the 20th century. Never have human lives been less private, less personal, more entirely dedicated to the cause of the revolutionary emancipation of the oppressed class, than the lives of these three of the most noble figures in the workers’ movement.

The proletariat doesn’t need idols:

the work of the great revolutionaries is an encouragement to fight

More than any other class in history, the proletariat is rich in fine revolutionary figures, in devoted militants, in tireless fighters, in martyrs, in thinkers and in men of action. This is due to the fact that unlike other revolutionary classes in history, who only fought against the reactionary classes in order to set up their own domination, to subject society to their egoistic interest as a privileged class, the proletariat has no privileges to win. Its emancipation is the emancipation of all the oppressed and from all oppressors; its mission is the liberation of the whole of humanity from all social inequalities and injustices, from any exploitation of man by man, from all forms of economic, political and social servitude.

It’s through the revolutionary destruction of capitalist society and its state, through the construction of a classless, socialist society, that the proletariat will carry out its historic mission and open a new era of human history, the era of real freedom and the flowering of all mankind’s potential. In the period of capitalism’s decline, only the proletariat and its emancipatory struggle provides the historic soil for all that is progressive in the aspirations, ideals, and all other areas of human activity. It’s in this liberating struggle of the proletariat that history has placed the living source of all the highest moral qualities: abnegation, lack of self-interest, absolute devotion to a collective cause, courage. But without any fear of falling into idolatry, we can affirm that to this day, apart perhaps from the founders of scientific socialism, the proletariat has found no better representatives, no greater guides, no nobler figures to symbolise its ideals and its struggle, than those of Lenin, Luxemburg and Liebknecht.

The proletariat has no gods or idols. Idolatry belongs to a backward, primitive state of mankind. It’s also an instrument for the conservation of reactionary classes and for the brutalisation of the masses. Nothing is more pernicious for the revolutionary struggle of the proletariat than the attempt to graft fetishism and idolatry onto it.

In order to triumph, the proletariat needs an ever-expanding, ever -sharpening awareness of reality and of its goals. It can’t draw the strength to go forward and accomplish its revolutionary mission from any form of mysticism, no matter how noble, but only from a critical consciousness drawn from scientific study and from the living experience of past struggles. For revolutionaries, the commemoration of the deaths of Lenin, Luxemburg and Liebknecht can never be a religious act. While it’s true that such leaders symbolise the ideals of the class, it would be more precise to say that they personify class consciousness at a given moment in history, that they are the most perfect crystallisation of the experience undergone through the struggle of the class,

In order to take its struggle forward, the proletariat has a continual need to study its own past, in order to assimilate its experience, to build on historical acquisitions, and thus to go beyond inevitable errors, to correct the mistakes it’s made, to strengthen its political positions by becoming aware of insufficiencies and gaps in its programme, and, finally, to resolve problems which have up to now remained unsettled.

For revolutionary Marxists, who abhor idolatry and religious dogmatism, to commemorate the “Three L’s” is to dig out of their work, their lives, their experience, the elements needed for the continuity of the struggle and the enrichment of the programme of the socialist revolution. This task is at the base of the existence and activity of the fractions of the International Communist Left.

Against the falsification of Stalinism:

Lenin’s real teachings

There is no more revolting example of the deformation, no more shameful case of the falsification, of the life of a revolutionary, than what the bourgeoisie has made of the work of Lenin. After hounding him, pursuing him with implacable hatred throughout his life, the world bourgeoisie has fabricated a false Lenin in order to dupe the proletariat.

It has used his corpse to render his teaching and his work inoffensive. The dead Lenin is used to kill the living Lenin.

Stalinism, the best agent of world capitalism, has used the name of this leader of the October revolution in order to carry out the capitalist counter-revolution in Russia. It has cited the name of Lenin while massacring all his companions in struggle. In order to drag the workers of Russia and the rest of the world into the imperialist struggle, it has concocted a Lenin who is a ‘Russian national hero’, a partisan of ‘national defence’.

The activity of Lenin, who was at all times a bitter enemy of Russian and world capitalism, and of all the renegades who have gone over to the service of capitalism, can’t be gone over in the space of a single article. His work found its highest expression in the following three points, which are situated at the beginning, the maturity and the end of his political life.

First of all, there was the notion of the party he put forward in 1902 in What Is To Be Done. Without a revolutionary political party, he insisted, the proletariat could neither make the revolution, nor become conscious of the necessity of the revolution. The party is the laboratory in which the ideological fermentation of the class takes place.

“Without revolutionary theory, no revolutionary movement.” Building and strengthening the party of the revolution was the cornerstone of his whole work. October 1917 was the historic confirmation of the correctness of his principle. It was thanks to the existence of a revolutionary party, Lenin’s Bolshevik party, that the Russian proletariat was able to emerge victorious in October.

After that, it was the defence of class positions against the imperialist war in 1914. Not only must the proletariat reject any national defence under a capitalist regime, but it also had to work, through its class struggles, for the defeat of its own bourgeoisie; this was the principle of revolutionary defeatism, which meant working for the fraternisation of the soldiers on both sides of the imperialist frontiers, for the transformation of the imperialist war into a civil war, for the socialist revolution.

Lenin denounced all the false socialists who had betrayed the proletariat and put themselves at the service of the bourgeoisie. He also violently denounced all those who, while paying lip-service to opposition to the war, hesitated to break with the traitors and renegades. He proclaimed the necessity for the formation of a new International and for new parties, in which the traitors and opportunists would have no place.

Finally, he demonstrated that the imperialist epoch was the last period of capitalism, the period of imperialist wars, and that only the proletariat could put an end to the war, through the revolution. This thesis of Lenin’s was confirmed by the outbreak of the revolution in Russia and then in Germany, which put an end to the First World War. It was again confirmed in a tragic manner when the defeat of the revolution and the physical and ideological crushing of the proletariat posed the conditions for the new world imperialist war of 1939-45. Lastly, Lenin demonstrated in 1917, in practice, that the transformation of society cannot come about through a peaceful process of reforms, but demands the violent destruction of the capitalist state from top to bottom and the installation of the dictatorship of the proletariat against the capitalist class.

The victory of the October revolution, the construction of the Communist International, the party of the world revolution, the fundamental theses of the International, were the crowning point of Lenin’s work, the culminating point, the most advanced position attained by the proletariat in the whole preceding period.

The death of Lenin coincided with the reflux of the revolution and a series of defeats for the proletariat. In this period of reflux, the absence of Lenin, the inspired leader, weighed heavily on the revolutionary movement. Lenin’s rich work was not exempt from errors and gaps. It is up to the revolutionaries of today to correct and go beyond the historical errors of the proletariat. But Lenin, through his work and his action, made a gigantic and decisive step on the road to revolution, and in this sense will remain an immortal guide for the proletariat.

Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Liebknecht:

Magnificent figures of the world revolution

The work of Rosa Luxemburg is still profoundly ignored today, not only in the broad masses, but even among experienced militants.

Rosa’s contribution to marxist theory made her the most brilliant and profound continuator of Karl Marx.

Her analysis the evolution of the capitalist economy provides the only scientific explanation of the final, permanent crisis of capitalism. It is impossible to seriously approach the study of our epoch of imperialism, of the ineluctability of the economic crisis and of imperialist wars, without basing oneself on Rosa’s penetrating analysis. By giving a scientific solution to the problem of the enlarged reproduction and accumulation of capital, a problem that Marx left unsettled, Rosa pulled socialism out of an impasse and reaffirmed it as an objective necessity.

But Rosa Luxemburg was not only a great theoretician and an erudite economist, she was above all a revolutionary fighter.

The uncontested leader of the left in German social democracy, she denounced the opportunist slide of the Second International at an early stage. At the head of the left, with her companion in arms, Karl Liebknecht, she broke during the course of the 1914-18 war with the traitorous social democrats who had passed over to the service of the bourgeoisie and of Kaiser Wilhelm.

The years of prison for her activity against the war didn’t dampen her ardour. On her release from prison she organised the Spartakusbund and threw herself into the struggle for the socialist revolution in Germany. On a number of points, history has confirmed the correctness of Rosa’s position as against Lenin’s, and in particular on the national and colonial question where Rosa denounced the error of ‘the right of nations to self-determination’, which was essentially bourgeois and historically reactionary, serving only to divert the workers of the small oppressed countries from their real class terrain, and thus strengthening international capitalism.

The events in the Baltic states, the Turkish national revolution, like a whole series of ‘national revolutions’ and China in 1927, were to give a tragic confirmation of Rosa’s warnings.

The new parties which the proletariat has to build today will only represent a step forward if they take up and deepen Rosa’s fundamental thesis on the national question. Certain other critiques, and certain of Rosa’s warnings about the Russian revolution, concerning freedom and violence in the revolutionary process, must also serve as material, together with the later experience in Russia, for the establishment of a new programme for the class parties.

Rosa’s extremely rich work must be subjected to a particularly attentive study by today’s revolutionaries. It is necessary to break with the scandalous and inadmissible ignorance that exists about it. As an example we can cite the surprising fact that the platform of the new Internationalist Communist Party of Italy refers to Lenin’s book on imperialism, without even mentioning Rosa’s fundamental work on this question.

******

Karl Liebknecht was the other leader of the German revolution of 1919. He was the most remarkable figure of a revolutionary tribune.

A deputy in the Reichstag, he broke the discipline of the parliamentary group of the social democratic party, and from the high tribune of parliament, pronounced his indictment of imperialist war.

“The main enemy is at home,” Liebknecht insisted again and again, and he called the workers and soldiers to fraternisation and revolt. His own ardour galvanised revolutionary energies, and the 1918 revolution found him and Rosa Luxemburg at the head of the proletarian masses, at the most advanced point of the battle.

By assassinating Karl and Rosa, by mummifying Lenin, the bourgeoisie merely postpones its annihilation

In order to save capitalism from the threat of revolution, German social democracy unleashed the most bloody repression against the proletariat. But the massacre of tens of thousands of workers wasn’t enough. As long as Rosa and Liebknecht were alive, it couldn’t feel safe. So it hunted them down and had them assassinated by its police after taking them prisoner. Hitler invented nothing; Noske, the Socialist minister and bloodhound of the bourgeoisie, gave him his first lesson and opened the door to him, just as Stalin taught him how to turn millions of workers and peasants into political prisoners and how to slaughter revolutionaries en masse.

******

The murder of Rosa and Karl beheaded the German and world revolution for years. The absence of these leaders was a terrible handicap for the international workers’ movement and the Communist International.

Capitalism can murder the leaders of the revolution, it can momentarily celebrate it victory over the proletariat by throwing it into new imperialist wars. It cannot, however, overcome the contradictions of its system, which hurl it into the maws of generalised destruction.

Lenin, Karl and Rosa are dead, but their teaching lives on. They remain a symbol of the fight to the death against capitalism and war, through the only way out for humanity, the proletarian revolution.

It’s by following in their footsteps, by continuing their work, by drawing inspiration from their example and teachings, that the international proletariat will bring about the triumph of the cause for which they fell: the cause of the proletariat and of socialism.

L’Étincelle. (January/February 1946)

Rubric:

Report on the National Situation: January 2019

- 360 reads

This report on the national situation in the UK was adopted by a recent general meeting. Its aim is to examine the historical background to the present political mess afflicting the British bourgeoisie.

Brexit and the historic decline of British imperialism

The true depth of the historical earthquake that has been shaking British capitalism can only be fully understood by placing it in its international context. The Resolution on the International Situation adopted by the 22nd ICC Congress[1], updated the Theses on Decomposition and drew out the following points:

- Decadent capitalism has entered into a specific phase - the ultimate phase - of its history, the one in which decomposition becomes a factor, if not the factor, decisive for the evolution of society.

- This process of decomposition of society is irreversible.

- Populism is, along with the refugee crisis and the development of terrorism, one of the most striking expressions of the decomposition phase.

- The rise of populism is not the result of a deliberate political will on the part of the dominant sectors of the bourgeoisie. It is an emanation of civil society that escapes the control of the bourgeoisie.

- The determining cause of this rise of populism is the inability of the proletariat to put forward its own response, its own alternative to the crisis of capitalism. In this situation of social impasse, the tendency to look to the past, to look for scapegoats responsible for the disaster, is becoming increasingly strong.

- The rise of populism has a common element that is present in most advanced countries: the profound loss of confidence in the 'elites' because of their inability to restore the health of the economy, to stem a steady rise in unemployment or poverty. This revolt against the current political leaders is a (reactionary) revolt that can in no way lead to an alternative perspective to capitalism.

- In the absence of a longer-term perspective of growth for the national economy, the living conditions of the natives can only be more or less stabilised by discriminating against everybody else.

In the period since the adoption of this resolution, the ICC has sought to deepen this analysis by placing this advance of decomposition within a broader historical framework. Central to this analysis has been the understanding that with the rise of populism we are seeing the terminal stages of the post-Second World War economic, imperialist and political structures. This is exemplified by the election of Trump and the political, economic and imperialist strategy of the fraction of US capital that he represents. This is a policy based on:

- the undermining of its main economic rivals (especially China) through trade wars;

- the support for the destabilisation of the EU through the encouragement of populist movements, Brexit etc, going so far as to call into question the World Trade Organisation (a pillar of post-war efforts to contain economic contradictions);

- the calling into question of NATO.

This attempt to overcome the USA’s economic and imperialist weaknesses by retreating behind the walls of the nation state, and doing all it can to undermine its rivals, is a direct challenge to the state capitalist policy of globalisation.

The main rivals of the US oppose this challenge. China, which has gained most from this policy, is presenting itself as the champion of globalisation. The EU has also benefited from, and is integrated into globalisation.

In this context of increasing struggles between the major powers over economic policy, the deepening of the economic crisis, along with imperialist tensions, will take on an even more chaotic character, threatening to throw world capital into lethal economic convulsions (due to the collapse of international cooperation) and explosions of imperialist tensions that could lead to the destabilisation of more regions of the planet.

British capitalism has been thrown into this whirlpool of international instability, chaos and accelerating tensions. A second-rate power, in danger of being cut loose from its most important economic market, has been left to fend for itself in a world increasingly marked by an economic policy of 'every man for himself' and protectionism. At the imperialist level, its ability to manoeuvre against its rivals in Europe has been severely undermined, while its ‘special relationship’ with the US has gone, with Trump openly trying to undermine the British government.

The end of Empire

Brexit is a major step in the historic decline of British imperialism from superpower to a struggling second-rate power. To understand the depth of this fall it is worth briefly analysing this decline[2].

The period of decadence has seen the decline of British imperialism, the ascent of the US, and the challenges of German imperialism, as laid out clearly by Bilan and the articles on the ‘The History of British Imperialism’. From the beginning of the twentieth century to the mid-1950s British imperialism strove to slow down its decline, particularly by greater exploitation of the Empire (exports to the empire in the 1930s were double those of the beginning of the century, as British capitalism bled the empire dry to offload the impact of the depression). However, US imperialism made very clear to British imperialism that the price of saving its bacon in the Second World War was the opening up and destruction of the empire, that is, the end of British imperialism's ability to use the empire as an economic and imperialist support. This marked the end of British imperialism as a world power, and an undermining of its economy.

This process of declining imperial and economic power did not happen overnight. Between 1945 and 1956 British imperialism tried to maintain its world power status by presenting Britain and its Empire/Commonwealth as a third global force. Labour and Tory administrations were consistent in their efforts to maintain a global role for British imperialism. This vision was the basis of the strategy towards Europe: that is, any developed relations with Europe had the aim of maintaining the UK's global position. Churchill pushed the idea of a United States of Europe, but in the context of his idea of the three circles of power: the US, Britain and Europe. This was basically the idea that Attlee, Bevin and the rest of the Labour government defended. It was the agreed position of the state. The main differences were over whether to maintain the idea of Empire and the Commonwealth, and the various ideologies which went with these ideas. Churchill maintained the idea of the leading role of the Anglo-Saxon race, whilst Bevin dressed up his defence of the continuation of the Commonwealth with ‘socialist' phrases. The idea of Britain’s role in a 'United State of Europe' was based on the assumption that the Commonwealth would also be involved in any such structures. Not surprisingly, the other European powers were not keen on subordinating their efforts to rebuild their economies to the interests of Britain and its empire.

This effort to maintain the Empire was constantly faced with the US’s insistence that the British open up the Commonwealth, i.e. subordinate it to US interests. The US also pushed for the British to be involved in Europe, as a counter-weight to France, and a possible emerging Germany, as well as to the Russian threat. The US also played off the other European powers against Britain. It supported the greater integration of the main economies. For the US, the idea of a ‘special relationship’ was a sop for the British to hide their humiliation. As one US diplomat pointed out, the US also had a ‘special relationship’ with Germany which was even more important given its geographical position and its re-emerging industrial might.

The British bourgeoisie may still peddle the myth of the ‘special relationship’ but they know full well that it is nothing but a fig leaf to hide their decline and the increasing power and domination of the US.

This was firmly underlined by the decision of Attlee's Labour Government to have an independent UK nuclear arsenal, and all the efforts the US made to stop this happening, or, once it had, to make sure that this arsenal would be subordinated to the US.

The dismantling of the Empire and its replacement with the Commonwealth increased the influence of the US on such important parts of the Commonwealth as Australia, New Zealand and Canada. These countries could see that Britain had to have closer relations with Europe and that this would have an impact on their dependence on the British market especially in agriculture. This pushed them towards the US. As did the need to defend their own imperialist interests: the Second World War had shown that British imperialism, on its own, was unable to defend its interests militarily.

After the Suez humiliation

This disentangling of the Commonwealth was strikingly confirmed during the Suez Crisis when Australia, New Zealand and Canada refused to offer military support to the British/French/Israeli adventure and sided with the US in its call for the ceasefire. This robbed the British bourgeoisie of any illusions it might still have had about using the Commonwealth to back up its efforts to remain a world power.

Thus, not only did Suez graphically illustrate to the British ruling class that the US would not support it uncritically but also, maybe more importantly, the main Commonwealth countries now understood that their best interests lay in supporting the US. In two world wars British imperialism had been dependent upon the support of the Empire/Commonwealth: now it was clear it was on its own. British imperialism by 1956 had been robbed of its Empire and seen the most important countries of the Commonwealth abandon it in time of crisis. Its illusions of being able to maintain its global role were brutally crushed.

This situation removed the basis of the consistent national strategy which the state had followed since 1945. Now the British bourgeoisie was faced with difficult choices about how to defend the national interest in a world where it was now a secondary power, and whose economic and imperialist interests pushed it increasingly towards closer ties with Europe. Previously the British bourgeoisie had approached Europe as part of its global strategy; now it approached it as a visibly weakened power. This was at a time when the rest of Western Europe was undergoing the post-war ‘boom’, in part based on a greater economic and political cooperation. There were important parts of the bourgeoisie that had close ties to the Commonwealth and could see that closer relations with Europe meant loosening ties with the Commonwealth. The Labour Party had always been very hesitant and opposed to closer relations with Europe because they felt it made their management of the national capital more difficult. There was also a strong weight of suspicion of a re-emerging German imperialism across the state and its parties. Even these elements understood that greater integration with the booming European economies was vital to slowing down and perhaps reversing the dramatic weakening of the British economy, although they never wanted to be part of a federal Europe. The need to go to Europe cap in hand underlined to the whole bourgeoisie just how far British imperialism had plummeted in 60 years and was one of the greatest humiliations for British imperialism: it graphically displayed to the whole world the depths to which this once great power had fallen.

The British bourgeoisie, in the late 50s and early 60s, was thus faced with a multitude of rivals seeking to push it further down the imperialist pecking order. There were also strong resentments about the loss of Empire, towards the US for bringing this about, towards the Germans as an historical rival, and towards French imperialism as one of the leading states of the Common Market (the EEC). To defend the national interest in this morass of historical and contemporary dynamics posed a huge challenge to British imperialism

The US drove home the weakened position of the British by putting enormous pressure on Britain to maintain its military commitments around the world (at a huge cost to a weakened economy) and to join the Common Market. Even if the British bourgeoisie had wanted to maintain its independence the US would not have allowed it. All of which reinforced tensions. The US wanted Britain in Europe because it would serve to counter the ambitions of Germany and France, but also in order to try and bolster the declining British economy as a potential market for its goods.

There were still parts of the bourgeoisie that strongly opposed the Common Market for various reasons: parts of the Labour Party due to their vision of a strongly centralised and ‘independent’ state, supported by the Commonwealth, as defended by Benn, Foot and other Labour lefts. In the Tory party there were those who had a similar vision of Britain and who could not accept the profoundly weakened position of British imperialism. Both of these factions cooperated closely in order to oppose the Common Market.

Once the entry into the Common Market was confirmed by the Referendum of 1975, the Labour government clearly stated British imperialism’s intentions to do all it could to defend its interests within Europe and to oppose all moves that might undermine its position. The Wilson/Callaghan government, for example, began the negotiations for a rebate. Thatcher continued this attitude and was able to do it with more intransigence due to the needs of the economy, with her image as the Iron Lady and her rhetoric of the Right in power. There was no real change of policy, it was simply down to a more ‘hard-line’ stance. However, when it served the national interest, Thatcher was willing to sign up to greater economic integration. Thatcher’s stance was not seen as being anti-European. In fact, the radicalisation of the Labour Party, under Foot, in the early 1980s, was to a large degree based on its opposition to the Common Market and thus Thatcher. Here we can see the British bourgeoisie using the long-term euro-scepticism of Foot, Benn etc to their own ends.

The fall of Thatcher in 1990 is integrally linked to the collapse of the Eastern Bloc. Thatcher had always been hostile to Germany. Her unlikely friendship with Mitterrand was linked to their mutual distrust of German imperialism. This hostility became increasingly open and counter-productive when she organised a symposium on Germany, at Chequers, just after the collapse. This brought together academics and others who clearly all had very hostile views towards Germany. When this meeting and its findings were exposed, this placed British imperialism in a very difficult situation faced with the inevitable re-unification of Germany and all that meant to the balance of power in Europe. Thatcher was given the boot by her own party.

Britain all at sea in the “new world order”

The deepening of decomposition marked by the collapse of the bloc system has been the historical context for the unfolding of the increasing difficulties of the British bourgeoisie in defending its imperialist interests internationally and in the EU. The instability of international relations, the widening imperialist chaos, the growing difficulties in managing the political game, mounting corruption of political life, all served to make the question of the relationship with the EU much more complicated. Thatcher could get away with ‘hand-bagging’ her way around Europe, in the national interest, when the blocs existed: all the bourgeoisies had a common enemy. Once the Russian threat went the common interest became more complex. Each national capital had to find its own way in this “new world order”.

This unstable situation put into question the ability of the EU to stay together, but at the same time led to the strengthening of the tendency towards integration in order to counter these centrifugal forces. This situation placed British imperialism in a very difficult situation. No longer able to punch above its weight in Europe, it was faced with moves to greater integration in order to try and stabilise the EU. The national interest was best served by careful and subtle diplomacy in order to allow British imperialism to defend its interests. We see the policy of the Major government, appearing to be more pro-EU than Thatcher, but aimed at continuing the policy of limiting the ability of Germany and France to use the EU for their own ends.

New Labour maintained the same policy. The Labour Party’s ability to look less anti-European than the openly faction-ridden Tory party enabled British imperialism to manoeuvre more easily in Europe. For example, the British state pushed for the extension of the EU into Eastern Europe and the Balkans in order to draw in countries that were historically antagonistic towards German imperialism and with whom British imperialism could try to contain and limit German capitalism’s domination of the EU.

This aspect of British imperialist policy took a serious blow with the debacles of Afghanistan and Iraq. British imperialism's efforts to get the main EU countries to support the war produced hostility, whilst its retreat from Afghanistan and Iraq with its tail between its legs left British Imperialism even more weakened as an imperialist power.

“British imperialism will find it very difficult to find a way out of the impasse and all but impossible to regain the power it has lost. At a practical level, the scale of the cuts in the defence budget means that it will be less able to intervene. The contradiction between its ambitions and this reality is revealed in the almost comic decision to build aircraft carriers without any aircraft. At the strategic and political level, it has to continue to acknowledge the reality of American power in the world and German domination in Europe. While the growing imperialist power of China and to a lesser extent other emerging countries like India offer new fields for action it is unlikely that the former will become a serious challenger to the US in the near future while the latter remains focussed on its regional ambitions. Moreover, the imperialist situation will continue to be characterised by great complexity since there is no real dynamic towards the formation of new blocs that would impose some order on the situation. The inescapable reality for Britain is that like most lesser powers it is dependent on grasping opportunities from the evolution of the situation that is shaped by greater or better positioned powers. Increasing the size of the special forces may enhance its ability to undertake covert operations but these can rarely gain more than tactical victories. In terms of developing networks beyond the major powers Britain has relatively little to offer such powers while the baggage it still carries from the days of empire and the legacy of its arrogance towards lesser powers and peoples that it retained even after the sun set on the empire is a hurdle to forging alliances of any duration or stability.” (Resolution on the National Situation, 19th Congress of WR, 2010)

This continued weakening of British Imperialism took place in the context of the 2008 economic crisis. Within the British bourgeoisie this added fuel to the long-standing historical divisions over Europe. The EU did not look such a pillar of economic stability. This helped to feed the rise of a faction of the bourgeoisie calling for an exit from the EU in the interest of the national economy: “a significant development over the last few years has been the growth of the view that sees withdrawal from Europe as being in Britain’s interests. A few years back this faction seemed largely restricted to the likes of UKIP but the attempt to force through a referendum on Europe last year revealed that it exists within part of the Tory party... While this points to the spread of incoherence within the bourgeoisie, since leaving Europe is likely to weaken Britain’s economy, as well as leaving it more isolated on the imperialist stage, it is unclear how wide-spread these views are in the Tory party. We suggested at the time of the last election that the right is dominant in the party and in a recent update that the majority in the party is Eurosceptic; both points may be correct, but this does not imply they all want to leave Europe or that they agreed with last year's call for a referendum” (ibid).

The emergence of populism in the UK

It is against this background of historical decline and divisions about how to deal with this decline that the growth of populism and its destabilising impact has to be understood. The already existing divisions have become dominant factors in the state’s efforts to control its political apparatus due to the instability caused by the rise of populism.

The disaster of Brexit underlines the historical paradox facing British state capitalism: its ability to control its own political apparatus and the social situation is being undermined by capitalism’s own rotting entrails - by decomposition and its political manifestation par excellence, populism.

This paradox is further deepened by the fact that the policies of the bourgeois state have themselves nourished the growth of this political chimera that feeds on all the anti-social characteristics of capitalism.

The proletariat in Britain had been the centre of a well-coordinated strategy by the state to smash its main militant bastions and to break its confidence in itself, from the end of the 70s and throughout the 80s. The collapse of the US bloc and the international reflux in the class struggle had a particularly powerful impact in Britain on the back of the defeats of the miners, car workers, steel workers and others. This has led to a historically low level of workers' strikes throughout the last three decades. This has, in turn, generated an increasing sense of hopelessness and an idea of the pointlessness of trying to struggle.

The abandoning of whole regions of the country, especially in the north and in Wales has bred lumpenisation with the destruction of the local economies. This has led to cities, towns and estates being left to rot, with high levels of crime, poverty and despair, leaving them prey to the most poisonous ideologies

In this social situation of decomposition, the state under New Labour developed, along with the media, a sophisticated ideological campaign of demonisation and scapegoating of those on benefits, the disabled, immigrants. A ‘reign of terror’ was imposed around the social security system with increasingly more difficult criteria for receiving benefits. At the same time, ministers condemned those on benefits. In the media, the mocking and condemnation of the poor became popular entertainment. Systematic campaigns to generate Islamophobia were carried out in the context of the fear of terrorism. The whole social atmosphere has increasingly become a morass of scapegoating, hatred, ridicule and contempt.

Migration had also become a more prominent question. The Labour Party, through its support for the extension of the EU into Eastern Europe and the single market, used the influx of migrants looking for work to stir up divisions in the class, and as sources of cheap labour. The state was fully aware that the already chronic supply of housing, schools and health care was going to be impacted by its policy, but the ideological divisions of the class were a very powerful weapon to divert any reactions to the attacks into blaming migrants. To give legitimacy to these divisions Gordon Brown made promises of "British Jobs for British Workers" (an old slogan of the neo-Nazi National Front in the 1970s, and Moseley's fascists in the 1930s). The LibDem/Tory Coalition government continued these campaigns.

The power of the democratic mystification was also tarnished by the campaign that followed the collapse of the imperialist blocs. This emphasised that that now the ideas of Left and Right are old fashioned, it's the centre, the Third Way that's the way forward. This campaign reinforced the idea of the defeat of the working class and its disappearance as a social force, so that the political parties become the mouthpieces of an indistinguishable and distant political class with nothing to do with the everyday lives of the population, especially the working class. This bred a real cynicism.

This cynicism was greatly reinforced with a series of parliamentary scandals which exposed MPs lining their own pockets whilst the population was being told to accept austerity.

The sense of the parliamentary system being a remote and alien world with no real connection with people had been given further impetus by the way in which New Labour had ignored the mass protests against the Iraq war. These pacifist demonstrations were well-organised attacks on any real questioning of the war, but they also led to a deep sense that nothing could be done. This compounded the feeling within the proletariat that strikes were no longer able to gain anything and there was nothing that could change the situation.

When UKIP emerged, it had a simple answer to all these problems: leave the EU. Its leader Farage appeared to be all that most politicians were not: blunt, politically incorrect, and condemning of the elite. Support for UKIP was fed by disillusionment in the established parties, in a context where the working class was not able to make its weight felt in society. Effective opposition to the main parties became identified with UKIP and its bizarre politics and behaviour,

UKIP and populism also played on a reactionary desire in the population faced with the increasing complexity of the world situation for a return to the 'good of days' - to find safety and comfort in the apparent stability of the past.

UKIP also tapped into a deep scepticism about Europe linked to this reactionary nostalgia, which saw membership of the EU as a constant reminder of the decline of British imperialism and its place in the world. The idea of ‘making Britain great again’ has a real weight as it did in the US Presidential campaign of 2016.

The referendum as a response to the populist tide

The rise of UKIP, which emboldened the Eurosceptic wing of the Tory Party, posed a real problem to the ruling class. How to limit the rise of the political “nutters” (as Prime Minister Cameron called them), because they were destabilising the British bourgeoisie's manoeuvrings around Europe? They posed the danger of the Tory party becoming infected with populism and increasingly destabilising the party. This was the reason the Cameron government took the decision to hold the referendum - in order to try and face down the rising tide of populism.

Within the bourgeoisie there was great unease about this tactic. For example, the then Chancellor George Osborne opposed the idea because he was convinced that the Remainers would lose. However, the Referendum went ahead. This led to the greatest political disaster for the British bourgeoisie since the Second World War, casting it adrift in an increasingly complex and dangerous world situation.

Why did Remain lose?

1. The central fraction of the British bourgeoisie completely underestimated:

- the depth of disillusionment and anger within the working class;

- the ability of the Leave campaign to channel this discontent into voting Leave, making the Leave vote as much about delivering a rebuke to the 'elite' as it was about leaving the EU. Leave's ability to mobilise 3 million voters who had either not voted before, or who had stopped voting, swung the referendum;

- The Remain campaign paradoxically fed this vote by its constant threats that there would be more hardship for those who were already suffering the impact of austerity.

2, “Events dear boy, events” (as Prime Minister Harold MacMillan might have said). A cocktail of international events served to generate or reinforce fears about remaining in the EU:

- the crisis in Greece,

- the euro crisis,

- the wave of migration,

- the rise of China and the emerging economies.

With the Eurozone apparently drowning in a crisis, and Greece looking like it might leave the EU or would suffer a terrible price in economic pain for remaining, it did not make the EU look an inviting proposition.

The terrible wave of fleeing humanity from the Middle East and Africa was cynically used to play on existing fears about migration and terrorism.

Faced with an EU apparently racked by crises, the idea of trading freely in the rest of the world market, especially the emerging markets of China, India etc, offered a rational alternative to parts of the bourgeoisie who were not tied to Europe.

These combinations of errors and events led to the Remainers losing the 2016 Referendum.

The British bourgeoisie greatly weakened

The result of the referendum has many debilitating consequences for the British bourgeoisie:

- Its ability to manage its political apparatus has been deeply damaged and there is now open warfare between different factions of the British bourgeoisie as it tries to deal with the immediate, medium- and long-term impact of Brexit.

- Its international reputation was already in tatters. A once powerful superpower was now reduced to looking like it had shot itself in the foot. It had already weakened its international standing and ability to manoeuvre by the fatal decision to support the US in the Second Gulf War.

- This international standing was placed in even more danger by the election of Trump. The Trump administration, and those in the US bourgeoisie that back it, may have an interest in weakening the EU, but Trump soon showed that he was not going to treat the UK any differently to any other country.

- Trump's rise, above all his calling into question all of the post-war political, diplomatic and economic structures, pulled the rug from under the feet of those who said Brexit would allow a better relationship with the US and the rest of the world market. British capital is about to turn away from its main market at the same time as competition on the world market is entering a new period of intensity. This for an economy that is already very weak competitively!

- Socially the atmosphere has become even more soaked in populist hate, rage, irrationality, racism, violence. This is not just on the Leave side: the bitterness of those who voted Remain is equally as marked by hatred for the 'white working class', the uneducated, the North.

- The life of the bourgeoisie has been thrown into deep crisis, as it struggles to cope with the aftermath of the vote. The whole parliamentary agenda has been totally taken up with Brexit. The apparatus of the state has had to take on the task of negotiating Brexit and organising for it, but in a situation of great weakness. However, the civil service, the backbone of British state capitalism, has tried to do this, despite the obstacles created by the politicians.

- The very integrity of the UK is now in doubt. The situation with the Northern Ireland border is one where no one is satisfied. Everyone says there should be no border with the rest of the UK and a frictionless border with the Irish Republic. But Northern Ireland can't be both in and out of the customs union at the same time. Also, the inclusion of Northern Ireland in the Withdrawal Agreement has revived nationalist tensions in Scotland where already the Scottish National Party has been warning that it will call for a new referendum if they are not happy with the final deal.

- The complete disaster of the 2017 general election, which was meant to strengthen the hand of the Tory party by increasing its majority, has led to the worst possible situation, a minority government supported by unreliable Unionists, even further narrowing the bourgeoisie's margin of manoeuvre.

The bourgeoisie’s response to this disaster

The current dilemmas of the British political apparatus have fully confirmed what we said in an internal text we wrote two years ago, regarding the paradox of populism: that it is both a product of disillusionment with the “democratic process” while also serving to strengthen the totalitarian grip of democratic ideology:

“The populist parties are bourgeois fractions, part of the totalitarian state capitalist apparatus. What they propagate is bourgeois and petty bourgeois ideology and behaviour: nationalism, racism, xenophobia, authoritarianism, cultural conservatism. As such, they represent a strengthening of the domination of the ruling class and its state over society. They widen the scope of the party apparatus of democracy and add fire-power to its ideological bombardment. They revitalise the electoral mystification and the attractiveness of voting, both through the voters they mobilise themselves and through those who mobilise to vote against them. Although they are partly the product of the growing disillusionment with the traditional parties, they can also help to reinforce the image of the latter, who in contrast to the populists can present themselves as being more humanitarian and democratic”.

Since the calling of the Referendum there has been a systematic campaign to revive the whole democratic mirage that was becoming tarnished. Despite the disaster of Brexit, the bourgeoisie has been able to focus the attention of society on its parliamentary circus, and with renewed vigour because they are desperate to demonstrate that that 'voting does matter'. By voting for Brexit, millions of those who had not voted for years, or ever, had a direct impact on the life of the ruling class. After the Referendum it has been a question of 'will parliament respect the vote?' For those who voted to Remain there's the question of whether they should accept the result or call for a new referendum. All social questions are focused on Parliament. In October 2018 there was one of the largest demonstrations ever in London, with 750,000 people marching for a second referendum, without any support from the main political parties, or big unions, or most leftist groups. All social and political life, as portrayed in the media, has been reduced to 'You are either for or against Brexit'.

The success in the revival of Parliament and democracy within the wider population has had a powerful impact on the proletariat. It was pulled into the referendum. Those regions, cities and towns most impacted by the economic crisis through the destruction of industry and the spread of lumpenisation voted in great numbers for Leave, although in these areas there were difference between the younger workers and the older ones. In other parts of the country workers came out to vote in favour of staying. The proletariat was divided up into for or against, young or old, uneducated or educated etc.

Since the Referendum these divisions have constantly been reinforced with persistent messages about defending the “will of the people”, or the talk about whether Leave areas have now changed to Remain. However, the revival of the parliamentary circus could again be weakened given the inability of any of the political parties to put forward a coherent plan This would lead to the further growth of cynicism and anger about the mess of Brexit.

But, above all, the working class is left standing at the edge of social events helplessly looking on as the ruling class battles it out over leaving the EU.

This democratic crusade has also been used to smother discontent with the last decade of austerity and its effect on the proletariat. This report will not go into the detail of these attacks, but it is necessary to underline the way that the growing discontent faced with these attacks has been diverted into the Brexit carnival. The government has acknowledged that there is a growing discontent but say that while they want to stop austerity this cannot be done until Brexit is finished. Any idea of a response from the class is lost in this constant cacophony about Brexit.

The strategy of the bourgeoisie faced with populism

The contribution ‘On the question of populism’, published in 2016[3], lays out three strategies that the bourgeoisie has used so far to confront the populist upsurge.

“Firstly, that it is a mistake for the 'democrats' to try and fight populism by adopting its language and proposals…

Secondly, it is insisted, the electorate should be able to recognise again the difference between right and left, correcting the present impression of a cartel of the established parties.

The third aspect is that, like the British Tories around Boris Johnson, the CSU, the 'sister' party of Merkel’s CDU, thinks that parts of the traditional party apparatus should themselves apply elements of populist policy.”

Faced with the referendum and Brexit, the British bourgeoisie has used options 2 and 3.

Adopting the polices of the populists

The bourgeoisie’s political machinery has tried to steal the fire of the populists and the Brexit hardliners, through:

- The leading factions of the Tory and Labour parties accepting the result of the referendum.

- May appearing to adopt a hard line on Brexit (“Brexit means Brexit”), talk of “red lines” about leaving the customs union, etc.

- Both parties said they will end freedom of movement for EU citizens, and introduce ‘fairer’ migration controls.

The first result of this strategy of stealing the populists’ fire was the collapse of UKIP. This small victory should not be underestimated.

Creating blue water between Labour and Tories

Corbyn’s assumption of the leadership of the Labour Party may not have been planned by the bourgeoisie but it has certainly helped them to implement the second strategy. There is now clear water between the Tories and Labour. The Labour Party, whose image as a party representing the downtrodden, seriously damaged by the leadership of Blair and Brown, was now presented as a radical party interested in defending the working class once again. This image has mobilised thousands of young and other people to join the party, and importantly won back to Labour voters who had been tempted by UKIP.

The Labour Party has been shaken by challenges to Corbyn from the Blairite wing, including the 172-40 vote of no confidence by Labour MPs in June 2016, which Corbyn was able to ignore. He and his team have beaten off such challenges with a clever use of the democratic mechanism of the party: 60% of the party's members and supporters voted for Corbyn.

The vote of no confidence was provoked by Corbyn’s immediate reaction to the Referendum result, saying Labour will respect the result and work for Brexit, but on terms that will keep it as close as possible to Europe. The Blairite wing blamed Corbyn for the loss of the Referendum due to his lacklustre campaigning, but it is clear that, for whatever motives Corbyn himself may have, the Labour Party is still wedded to the bourgeoisie's attempts to deal with the impact of Brexit.

The various campaigns against Corbyn, plus the behind-the-scenes arm-twisting by the state, have served to make him and his team more acceptable as a possible government. They are now in a position to defend the bourgeoisie’s policies, even including a second referendum if this is thought necessary, and to replace May if required.

All this might make it seem that social democracy in Britain is going against the general trend of the decline of socialist parties in France, Germany, Italy, Spain, Greece etc. What must be added to the picture are the divisions within the British Labour Party. It is divided over Brexit, there is a division between the membership and the majority of MPs, and there is a division over whether to confront anti-Semitism in its ranks. Any of these divisions, if deepened, could seriously weaken the Labour Party. And, if it came to power, it would have to continue with the imposition of austerity, which would further exacerbate its internal divisions.

Trying to control the Brexit process

As the ICC has said since the Referendum, the bourgeoisie has accepted the outcome of the Referendum in order to steal the fire of the populists and also because it does not seem to have another option. To resist Brexit would pour petrol onto the flames of populism. Thus, the state has been working to try and control the Brexit process in order to gain the best deal it can, in a very difficult and unfavourable situation.

Both main factions of the two main parties accepted Brexit and the need to get the best deal.

Through May the state has sought to corral the hardliners through:

- May’s apparent support for the possibility of a no deal Brexit: “no deal is better than a bad deal”. This has left the hardliners wrongfooted because they did not know if she was really supporting this position or not;

- the inclusion in the Cabinet of all the main popular Brexiters: Johnson, Davis, Gove, and giving them positions of responsibility in the Brexit process;

- May constantly holding out the threat of a Corbyn government if the hardliners caused too much instability.

At the same time, the state, which controlled the negotiations, did all it could to get the best possible deal.

The final outcome of the negotiations over the Withdrawal Agreement has shown that this strategy has at least allowed the state to negotiate some kind of deal with the EU. It also clearly demonstrated that May had been blatantly deceiving the hardliners with her claim that “No deal is better than a bad deal”

The fury ignited by the Withdrawal Agreement was not a surprise to the state and to May. Even before the Agreement was published, the government had informed the media of its details in a 4-week campaign to sell the deal. They used this against the hardliners to:

- expose Brexiters as having no coherent plan for Brexit;

- put those Brexiters still in the cabinet into a bind: either bring down the government or accept the deal. The decision of Michael Gove and others to remain in the Cabinet was a real blow against the hardliners;

- the European Research Group, a group of hard-line Tory MPs has been outmanoeuvred. They fell into the trap of talking about leadership challenges but were unable to mobilise enough MPs to call for the removal of May;

- the idea of a no deal Brexit, crashing out, has been made to look like the policy of arrogant and irresponsible hardliners.

This policy of facing down the hardliners appears to have had some success. However, given the depth of irresponsibility shown by parts of the bourgeoisie who have been nourished by the spread of the poison of populism and decomposition, this whole approach could lead to a new explosion.

The perspectives

The historic depth of the crisis engulfing the ruling class and its impact on society, especially the proletariat, cannot be underestimated. The state may be able to get its Withdrawal Agreement through, but this is only the first step. It still has to negotiate a future political and economic relationship with the US, along with seeking to navigate the increasingly stormy water of the world situation. A task that is going to underline just how destructive Brexit has been to the British ruling class, politically, economically and at the imperialist level.

Losing the relative stability it had when in the EU is going to create more and more difficulties for a ruling class that is already deeply divided over the policy for British capital in this new period. The complexity and instability of the world situation can only generate even more tensions within the ruling class itself. The instability caused by the divisions over Europe are a foretaste of those that will come as the bourgeoisie is faced with having to take increasingly difficult vital decisions about the national interest.

The outlook for the proletariat is very sobering. The impact of the ideological battering over the past few years and for the foreseeable future has been extremely harmful. The divisions produced by the referendum and Brexit will be used by the ruling class to do all it can to undermine the inevitable discontent within the proletariat faced with continuing austerity. The proletariat in Britain was already disorientated and demoralised before the Brexit fiasco due to the crushing defeats of the 1980s. Brexit and the initial periods following it are going to increase this disarray in the class.

However, the economic crisis will continue to deepen, and will be exacerbated by the economic turmoil caused by Brexit. These attacks will generate discontent and reflection, even among a weakened fraction of the class. But it will be the international struggle of the proletariat that will be vital to the ability of the proletariat in Britain to overcome the further setbacks it has suffered with Brexit.

The coming period is going to be one of deep and persistent problems for both the bourgeoisie and proletariat in Britain.

World Revolution

January 2019

[1] International Review 159, https://en.internationalism.org/international-review/201711/14435/22nd-i... [2]

[2] The following articles are essential reading for understanding the historical context: - WR 212 and 213 ‘Evolution of British imperialism’, reprinted from Bilan

- IRs17 and 19 ‘Britain since World War 2’

- WR 216 and 217 ‘History of British imperialism’

[3] International Review 157, https://en.internationalism.org/international-review/201608/14086/questi... [3]

Rubric:

You can’t have a green capitalism

| Attachment | Size |

|---|---|

| 8.38 KB |

- 560 reads

Every day the evidence for the environmental catastrophe grows more alarming: melting glaciers, fires and floods linked to global warming, massive extinction of species, unbreathable air in cities, plastic waste building up in the oceans: it’s almost impossible to keep up with the coverage in the media and the press. And virtually every article you read, every speech by celebrated scientists and authors, ends up by calling on the governments of the world to be more committed to protecting the planet, and the individual “citizen” to use their votes more responsibly. In short: it’s up to the bourgeois state to save us! The youth marches for the climate and the protests by Extinction Rebellion don’t escape this rule. The indignation of the young people involved in them is very real, but so is the total inability of these campaigns to get to the roots of the problem.

It’s capitalism that is destroying the planet

170 years ago, in his book The Condition of the Working Class in England, Friedrich Engels was already pointing out that capitalism was undermining the health of the exploited class through the poisoning of the air, water and food, and by herding the workers into disease-ridden slums.

While, on the one hand, it was developing the productive forces, this new industrial system was generalising pollution: “In these industrial centres, the fumes from burning carbon had become a major source of pollution… Numerous travelers and novelists described the scale of the pollution pouring out of industrial chimneys. In 1854 Charles Dickens, for example, in his famous novel Hard Times, evoked the filthy skies of Coketown, a fictional town that mirrored Manchester, where all you could see were the ‘interminable serpents of smoke’ hanging over the city”.[1]

The responsibility for this pollution that was not born yesterday lies with a social system which exists only to accumulate value without any concern for nature or humanity: capitalism.

The great London smog of 1952[2] is a more recent example of atmospheric pollution resulting from industry and domestic heating, but today the world’s biggest cities, with Beijing and New Delhi at the top of the list, are faced with new varieties of the same phenomenon becoming more or less permanent. One of the most polluting sectors today is maritime transport whose low costs are a vital component of the entire world economy. But the accelerating destruction of forests for logging, palm oil or meat production is equally determined by the demand for profit. In every branch of its activity, capitalism pollutes and destroys without regard for the consequences.

The pollution of the atmosphere is today reaching apocalyptic levels. Whatever the ‘climate skeptics’ may say (with the generous backing of the oil and chemical industries), numerous scientific measurements of the retreat of glaciers and of the temperature of the oceans go in the same direction and leave no serious doubt about the issue: because of the increasing rates of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere, the average temperature of the Earth is rising inexorably, resulting in a series of unpredictable climatic phenomena which are already having a dramatic impact on populations in certain regions of the world. According to a study by the World Bank, the aggravating effects of climate change could push more than 140 million people to migrate within their own countries by 2050.

In other words: capitalist industry is threatening civilisation with a gradual but ineluctable slide into chaos. This sinister reality is giving rise to a widespread and very understandable disquiet. The question “what kind of world are we leaving to our children” is being posed everywhere and it’s quite logical that children and young people are the first to be concerned about growing up in a rapidly degrading environment.