November 2018

- 88 reads

Internationalist Voice and protests in the Middle East

- 350 reads

In August Internationalist Voice posted a position on the ICC's web forum[1] on the wave of protests in the Middle East affecting the countries of Jordan, Iran and Iraq. It defends fundamental class positions and the proletarian perspective of revolution and, within this, the necessity for the self-organisation of the class against the various traps of the bourgeoisie. The text raises a number of pertinent questions: what is the content of the demonstrations? What is the role and attitude of revolutionaries to these protests? Is there a revolution going on here? What is the role of the bourgeoisie? But on a secondary level there are a number of important ambiguities in the text, particularly on the class nature of these events.

For our part, we do view these protests as expressions of the working class, as part of the class struggle at a certain point of its unfolding. This is not a revolution, but a class that won't fight for its basic conditions of life is not going to make a revolution, and street protests have historically always been part of the class struggle.

The text is fairly dismissive of the protests and strikes in Jordan and underestimates the strengths of both. Like Iran and Iraq, the demands of the protesters in Jordan were clearly demands of a working class struggle: jobs, healthcare, rent, services, against corruption (the latter easily recuperated but in this context part of the indignation of the class). In all three countries, the struggles immediately came up against the trade unions who were ill-equipped to deal with them, including the "new" unions in Jordan set up by the bourgeoisie following the intense wave of struggle a decade ago. Workers actively sought out protesters and were explicit about the unions trying to divide them and keep them away from the protests. For It the protesters here weren't "fully radical", but what does that mean? The protests did seek to join up with workers on strike; and the workers, who refused to be isolated in the factories and places of work by the unions, which can easily become a prison even in the most advanced struggles, joined them on the streets. Indeed we can say that any workers’ struggle that doesn’t seek to come out onto the streets cannot advance towards a wider class unity.

So the demands of the class were there and the proletarian method of struggle was there, and while it wasn't a "fully radical" revolution it showed some important indicators of the class struggle, not least the hostility towards the unions, the rejection of the clerics in all three countries as well as the rejection of "national sacrifice". Moreover, the strength of the movement to some extent pushed back the bourgeoisie and obliged it to pause its attacks.

It's clear that there are enormous problems and potential dangers confronting the working class in these countries, coming from the specific forces in play and the wider dynamics of the major imperialisms. The ICC laid out these potential dangers in a position right at the beginning of this phase of struggle in January, though these related to Iran particularly[2]. But, even given the imperialist cauldron of the Middle East, or partly because of it, the combativity of the class is an important starting point and an example to workers everywhere. It is somewhat contradictory about this: it says that there is no future context for these protests but describes how youth "has provided the necessary social force for street protests" and placed the movement squarely in the crisis of capitalism and its attacks. It says that, along with the class composition of those who participated in them, "the demands and objectives of the protests determine the nature of that movement". That's true, but more generally the nature of the movement can also determine its demands and objectives. It seems to want to "fix" situations whereas the nature of these movements is fluid. And It draws a conclusion that's nowhere verified by the facts: "The fact is that... nationalist slogans overshadow the protests". Without underestimating the dangers of nationalism, especially in countries which have been dominated by bigger imperialist powers for a long time, we can say that nationalist slogans in all three countries were by no means the distinguishing feature of the strikes and protests. And even where nationalist slogans are raised, the only way they can be fought is through resolute action on a class basis, which can only bring the workers into conflict with the national interest.

It's on Iraq that the position of It most clearly goes off the rails. The workers are atomised, it says, but the proletariat in Iraq is in "a better position" and from this "contrary to the anarchist view, the power of labour is not on the street but in the workplace where it disturbs the process of capitalist accumulation" and consequently "... if the Iraqi working class stops oil exports, the regime will collapse and the workers will assert their power as a social class".

It’s true that the power of the working class can indeed be to prevent the factories or oil refineries from functioning, but their real power does not lie in the paralysis of the production and the circulation of goods, but in their unification across all sectors of the economy, not by isolating workers from each other through “besieging” places of production, but by spreading a movement and overcoming any attachment to a specific work place.

Indeed, we've seen from specific struggles of oil workers in France relatively recently that concentrating on one sector, even the oil sector, is the kiss of death for class struggle. The lessons of the isolating function of corporatism, which litter the history of class struggle, apply just as much to Iraq as France and everywhere else - isolation and division are the exact opposites of the needs of the struggle.

The oil industry in Iraq has erected many obstacles to the development of class struggle; various countries of the west and Iran and Russia have their installations guarded by their own militias and special Iraqi units have responded ruthlessly against protest around the oil plants. Indeed, mafia-like, the Iraqi militias have put their own soldiers on the books of the oil companies in exchange for "protection", and the Americans and British in the Green Zone fortress unleashed their "anti-terrorist" forces against the protesters in order to protect their own interests.

To make matters worse, Iraq could be descending into a post-Isis[3] phase of fracture, more and more dominated by centrifugal tendencies which are being expressed by the local gangs and manipulated by the major imperialist powers. There is a danger of Iraq turning into another Libya or something like it. Neither nationalism nor democracy are the main cards being played here – rather we are seeing the remorseless spread of capitalist decomposition. The flourishing of various militias in constant rivalry with each other is a clear expression of this, and this could sideline and overwhelm any class movements. In the meantime the response of the Iraqi state has been lethal gunfire, mass arrests and torture.

For It workers in these protests do not have "a clear horizon or class outlook to their aims". But these attempts of street protests and strikes to complement each other are parts of attempts to push forward the collective struggle and It makes a false division between protest and strike, the street and the workplace. The "unclear goals" of the struggle are certainly weaknesses in the sense that they do not yet pose the question of overturning capitalism, but at the same time the recent protests and strikes in the Middle East should give us encouragement: the willingness to come out and fight is an absolute necessity for the class struggle, not a weakness.

The workers in the Middle East, beset by imperialist war and ethnic conflict, have a particular difficulty in developing a political perspective which looks towards a communist society, and they will not be able to achieve this in isolation from the central battalions of the working class in the heartlands of capital. But this lack of perspective is a problem which affects the working class everywhere today. Workers in all countries are confronted with growing social decomposition precisely because the important waves of class struggle between 1968 and 1989 remained on an essentially defensive terrain. And yet it remains the case, both in the peripheries and the centres, that the extension and unification of defensive struggles is an indispensable basis for any future evolution from the defensive level to the level of the revolutionary offensive.

Baboon, November 2018

[2] The text is here in French: https://fr.internationalism.org/revolution-internationale/201801/9649/ma... [2]

[3] Isis is not entirely defunct and remains a potent force for imperialist chaos in the region.

Rubric:

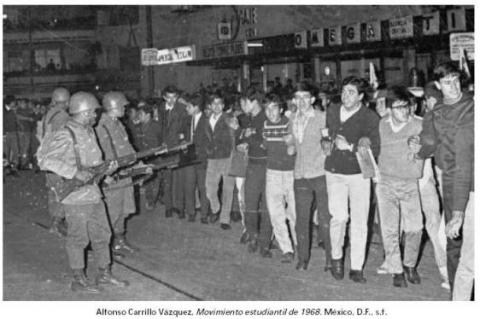

Mexico, October 1968: The massacre at Three Cultures Square, Tlatelolco, shows the real face of capitalism

- 379 reads

It's been estimated that between 300 and 500 people were massacred by the army on October 2 1968 on Tlatelolco Square. While the exact number, and still less the official list of the victims, is unknown to this day, the bourgeoisie has been able to exploit its own crimes. Some years after the massacre, the Mexican bourgeoisie began to consider this date as the starting point for the advance of democracy, as if the blood spilt had washed away all traces of this crime and consigned authoritarianism and repression to a distant past.

The speeches and commemorations around the fiftieth anniversary of the massacre have been used to re-launch the democratic campaign and, making the link with past elections, they pretend to show that the Mexican state has changed its face because democracy has taken power and even allowed for alternate governments. The bourgeoisie has also resumed its hypocritical wailing, letting its crocodile tears flow in order to try to distance itself from the crimes of 1968 and profit from the memory and from the still-present indignation among the exploited.

The demonstrations led by the students between July and October 1968 were, without any doubt, the expression of a strong social discontent which, even if their claims were limited by a desire for "democratic freedoms"[1] and even if the political scene was occupied by a heterogeneous social mass, had a certain continuity with the combative spirit re-awakened by the strikes of the rail workers in 1958 and the doctors in 1965. This movement didn't succeed in moving onto proletarian ground, or in raising demands belonging to the working class, but it did succeed in deploying and arousing strong forces of solidarity. That's why, 50 years after the events and the massacre, it is necessary to reflect on this by trying to go beyond the lack of conscience displayed by the Mexican state in its "celebration"[2] of the Tlatelolco massacre and the campaign of mystification created by the bourgeoisie through its "intellectuals" and its left political apparatus.

What triggered the demonstration?

In 1968 the Mexican state said that the student mobilisations could be explained as an "imitation" of May 68 in Paris, and that it had been incited by "foreign infiltration". A month before the government of Diaz Ordaz carried out the massacre against the students, the official trade union, CTM, repeated this idea: "Foreigners and bad Mexicans acting as active agents for communism, used the relatively unimportant scuffles of two small groups of students in order to launch a serious attack against the regime and the institutions of the country, adopting tactics similar to those adopted by extremists of these tendencies in other events and very recently in the outbursts in Paris..." (Manifesto to the Nation, September 2, 1968). Although there really was a global tendency towards social agitation influenced by the Paris demonstrations, it's false to suggest that these demonstrations were developed as no more than a sort of "fashion".

It was the return of the economic crisis onto the world scene which led to the workers' response of May 68[3] and it's the same trigger which opened the perspective for workers' responses in Italy (1969), Poland (1970-71), Argentina (1969) and even in Mexico which, without being a source of workers' mobilisation, aroused wide-scale social discontent.

It was also true that in the framework of the Cold War the dominant and competitive imperialist factions (the US and the USSR) used espionage and conspiracies, but up to now there's been no evidence that the USSR was implicated and still less the Cuban state, which had finalised an agreement with Mexico not to give its support to any opposition group[4]. It was similar for the "Communist Party", the Stalinist PCM which, although it was a pawn of the USSR, hadn't the strength or sufficient presence to lead the demonstrations.

On the other hand, the United States was keeping an eye on its "back-yard" and took an active part in the repression[5] during these years as during the whole of the Cold War.

In order to explain the origins of these demonstrations and the strength that they showed, it's necessary to go beyond the accusations of the government, but also to go deeper than the simplistic arguments about a "generational conflict" or an absence of "democratic liberties".

The students, as a social mass made up of diverse social classes but in which petty-bourgeois ideology dominates, were certainly held back by their illusions in democracy[6]. But another element pushed these students, who were often of proletarian origins, towards politicisation: the growing uncertainty that they felt in the future that awaited them. The promise of "social promotion" that the industrialisation of the 1940's to the 60's offered to the university students more and more clearly appeared as a come-on, given that, although capitalist profits increased, the life of workers got no better and threatened on the contrary to get worse under the pressure of the re-emergence of the world economic crisis which had already begun to make itself felt. But even more than this uncertainty, the repression of the state against the protests of workers claiming higher wages exacerbated the anger. Time and again bullets and prison were the responses of the state against the workers: the miners of Coahuila (1950-51), the rail-workers’ strikes (1948-58), teachers (1958) and doctors (1965). It was evident that even while increasing the rhythm of production, capitalism was not able to offer lasting reforms to a new generation.

In these conditions, the demonstrations were fed by the courage and indignation of the workers who, in the preceding years had also been hit by state repression.

Democratic hopes sterilise the strength of solidarity

From the 1940's to the 70's, the Mexican bourgeoisie unleashed an intense propaganda in order to make it known that industrialisation, the motor of economic growth and the stability of prices, would ameliorate the quality of life of the active population. In this process of industrialisation, the state played a fundamental role in taking responsibility for direct investments and supporting private capital through the sale, often underpriced, of energy resources, but above all through a policy of wage controls combined with subsidies for goods consumed by the workers. With these measures it presented itself as the "welfare state" while reducing the cost of labour for business, thus favouring the growth of capitalist profits. In the process of industrialisation there was a growing need for qualified workers, hence the state’s expansion of enrolment in the universities and the higher education schools. This increased the number of students of proletarian origin, thus making these institutions poles of social tension.

In this sense, the student movement in Mexico 1968, organised within the National Strike Committee (CNH), represented an important force, but structured around oppositional visions which never went beyond the stage of democratic demands it wasn't able to free itself from its links with nationalist ideology. However there was a certain class instinct which had germinated in the heat of the demonstrations and which pushed the young students to aim to meet up with the workers through the continued presence of the "information brigades"[7] in the industrial areas and workers' quarters. They thus succeeded in awakening a force of solidarity among the workers, but this potential social force was contained and cancelled out through the CNH’s lack of political perspectives.

Only the working class has an alternative to capitalism

From the first demonstrations of the student movement at the end of July 68, the granaderos riot police and regular police units acted with great ferocity. Mexican Chief of Police, General Luis Cueto, justified the repression in a press conference, saying that it was: "a subversive movement" which was tending "to create an atmosphere of hostility to our government and country on the eve of the XIX Olympic Games" (El Universal, July 28, 1968).

A period of continued street fighting thus opened up during the course of which the riot police were outnumbered. The army was then called into action and unleashed its repression. From the first days of the protests the army attacked with such savagery that on the night of July 30, it fired a bazooka at a school.

As the police and the army intensified the ferocity of their interventions, solidarity among the workers grew but it didn't take an organised form that could stamp its presence on the social scene.

The sympathy of the workers was demonstrated by their individual presence or in small groups joining the street protests. It was the same workers who, in the previous years, had already suffered repression for giving their support or direct participation to the social movements. Attempts were also made to openly express their solidarity with the students: on August 27, doctors at the General Hospital organised a strike in solidarity. The next day, municipal workers of the capital, forced to participate in an official action aiming to discredit the protesters, spontaneously rejected the government's move, by chanting "we are sheep" making it clear that they were obliged to be there and thus undermining the wished-for participation in this demonstration; they were then vigorously attacked by the riot police.

The student movement succeeded in arousing sympathy and solidarity and although numerous groups had shouted in the streets and painted on the walls "We don't want the Olympic Games, we want revolution", the truth is that these movements went forward without any real perspective. This is not because of a "strategic error", but because of the absence of the working class as a class on the social scene. It's not enough to be present individually or expressing solidarity in an isolated way, that is only formally occupying the social ground while leaving one's own political perspectives to one side. In 1968, although great numbers of the students were of proletarian origin and although the workers themselves showed their sympathy towards them, the proletariat did not find itself as an organised and conscious force able to confront capitalism.

The Tlatelolco massacre is a product of capitalism

By September, the response of the state became more and more aggressive. The army occupied the buildings of the UNAM on the 18th, reporting back on the political activity of the IPN[8] and the quarters around them, and the reason for this was that four days later the buildings of the polytechnic school were attacked. There were violent conflicts during this period in which solidarity again developed with a remarkable presence integrating school students and with the strengthened support of the population of the area...The massacre was being prepared.

On October 2nd, at the end of a demonstration on Tlatelolco Square, military and paramilitary squadrons attacked the students, showing in its naked form what the domination of capitalism meant.

The savagery of this response by the state is often presented as "a moment of madness" by the then Secretary of the Interior, Luis Echeverria, feeding the paranoia of the President Diaz Ordaz, but the brutality of this repression was neither accidental, nor the result of one pathological individual, it was part of the essence of capitalism. One of the main supports of the state is its repressive apparatus. To reflect on this properly we shouldn't forget that as long as capitalism exists, massacres like this one of 50 years ago will continue.

State violence is not a problem of the past, it is part of the very essence of capitalism, as Rosa Luxemburg had already analysed: "Violated, dishonoured, wading in blood, dripping filth – there stands bourgeois society. This is it [in reality]. Not all spic and span and moral, with pretence to culture, philosophy, ethics, order, peace, and the rule of law – but the ravening beast, the witches’ Sabbath of anarchy, a plague to culture and humanity. Thus it reveals itself in its true, its naked form" (The Crisis of Social Democracy, 1916).

Although the bourgeoisie does have a need to ideologically justify its existence as a dominant class and present its system as a perfect expression of democracy, the truth is that it bases this existence on exploitation, which involves the permanent use of violence and terror and which it uses on a daily basis in order to maintain its power and its domination; bloody repression is also a part of its way of life.

Tatlin for Revolucion Mundial, Mexican section of the ICC, September 2018

[1] The six inoffensive and somewhat naive points claimed by the National Strike Committee (CHN) were:

- Freedom for political prisoners;

- Resignations of Generals Luis Cueto Ramirez and Raul Mendiola;

- Disbanding of the grenaderos, the special police units used against the struggle;

- Abrogation of Articles 145 and 145 (2) of the Penal Code (dealing with subversion and social agitation);

- Compensation for the families of the dead and wounded caused by the repression;

- Going after and arresting those within the police and the special forces of the army responsible for the repression.

[2] In this pretentious manner, the bosses of the university have proudly announced that they've planned a series of commemorative events beginning October 2, during the course of which they will spend 37 million pesos (about 2 million dollars).

[3] See our article "Fifty years since May 68" and "May 68 and the revolutionary perspective" parts one and two on our internet site.

[4] Jose Luis Alonso, a Mexican guerillero exiled to Cuba in the 1970's, declared in an interview: "Three days after our arrival (in Cuba) Manuel Pineiro, Cuban Information Minister, read a statement to us: "(...) The first condition for admission to the territory (is that) there will be no guerrilla formation in the framework of the priority given to the respect for the good relations between Mexico and Cuba..." El Universal, May 22, 2002. In the same vein is the witness of Alfredo Campa who said: "We welcome those who come but we give priority to our cordial relations with the Mexican government..." (Proceso, May 4, 1996).

[5] The ex-CIA agent, Philip Agee, in his book Inside the Company: CIA Diary named the direct collaborators with the CIA as the Mexican presidents Lopez Mateos, Diaz Ordaz and Luis Echeverria, but also members of the political police like Gutierrez Barrios and Nazar Haro.

[6] That was the motive for the speech at the time by Barros Sierra, Rector of the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM), in which he called for the defence of the Constitution, autonomy and freedom of expression while appealing to nationalist sentiments by lowering the flag to half-mast and singing the national anthem. This was generally used as a reference by the student movement of July 1968 in Mexico.

[7] Already in 1956, on the backs of the rail and teachers' strikes, the "Information Brigades" took a variety of forms but were clear elements of the self-organisation of the students which included reaching out to workers by going directly to factory gates, schools and markets. They organised and sometimes appropriated transport for the distribution of leaflets and facilitated open spaces in the streets for spontaneous discussion and mass meetings. See: Rebel Mexico: Student Unrest, Authoritarian Political Culture During the Long Sixties by Jaime M. Pensano.

[8] The Autonomous National University of Mexico, (UNAM) and the National Polytechnic Institute (IPN) are the principal higher education centres of the public sector.

Rubric:

November 11, 1918, wasn't "War, never again" - it was an armistice to save capitalism and prepare for new wars

- 188 reads

November 11, 2018: exactly one hundred years after the Great War was ended. The "celebrations" planned and organised by the ruling class have been many and spread widely by the media. At a ceremony in Paris, Trump, Putin and Erdogan, amongst others, paraded themselves in the limelight; kings, queens, generals, bishops and politicians from right to left were all wheeled out to do their bit; ceremonies took place in cities, towns, villages and hamlets supported by various businesses, charities and supermarkets; youth events were organised, including "peace concerts" aiming to indoctrinate the young; marches, events and "silences" were organised way in advance across Europe, particularly Britain, France and Belgium with further commemoration events in Australia, New Zealand, India and Northern Ireland.

This was a deliberate, massive, organised and oppressive campaign, the primary function of which is to take one of the biggest atrocities of capitalism and turn this crime against the main victims of its imperialist wars, the working class, while trying to instil false conclusions from it. Not only does the working class have to suffer the atrocities of capitalist war, it is then forced, shamed, into "celebrating" its anniversaries with such hypocrisies about "sacrifices for freedom, justice and peace" and "the war to end all wars", and "never again". But there is no justice, peace and freedom for the working class: the war to end all wars was just the beginning of a worsening spiral downwards and rather than "never again", imperialist war has not stopped for a hundred years to the point that its ever-developing production of the means of destruction now threatens the very existence of humanity. The whole armistice celebrations have nothing to do with respecting the war dead but on the contrary insults them with lies and crocodile tears about "worthy sacrifice". With fake news we have fake history where words are turned into their opposite: massacres become sacrifice, ruin becomes civilisation and war becomes peace. In short, the whole armistice "remembrance" anniversary is nothing but a generalised attack on the consciousness of the working class, aimed at hiding the necessity for its revolutionary struggle for a peace and freedom that capitalism will fight tooth and nail against.

1. The armistice: a pause in order to prepare for new wars

In November 1918, Europe was plunged into enormous chaos; millions of people had been driven out of their houses and regions and were looking for somewhere to continue and rebuild their lives. Thus millions of Belgium's were refugees in Holland and more than 100,000 returned after the armistice: 300,000 Belgian refugees lived in France and returned in 1918. Further, there were hundreds of thousands of wounded, mutilated and invalided soldiers roaming across Europe looking for their town or village. Because of the chaos of the world war, the massive migrations that accompanied it and the exhaustion of the population, Spanish Flu made terrible ravages and in the final account caused more deaths than the world war itself. The thinkers of the bourgeoisie are in agreement on the fact that the conditions imposed by the Allies through the Treaty of Versailles posed the germs of a new war twenty years later. The "Peace Treaty" aroused the development of sentiments of revenge and retaliation which spread through wide layers of the German population during the 1920’s. The commentator for the Social-Democratic (SDAP) daily paper in Holland 1919 gives a taste of it: "This peace for all is viewed with bitter disillusion; a deception felt as a catastrophe (...) The Peace Treaty sets the status for a Europe in decline, of its retreat to an inferior level of civilisation. Most people on the continent are enchained and condemned to forced labour (...) humiliation and bitterness. Rancour here, sufficiency there, the thirst for power, fear: these are the new ‘civilised traits’ generated by the peace treaty" (Het Volk, 21.06.1919).

The bourgeoisies of various countries was fully aware that this peace was condemned to failure. It wasn't only the policy towards Germany that aggravated the anger but also, "the creation of new states like Poland, Austria, Hungary and Yugoslavia led to incessant conflict over the new frontiers of these countries. That particularly concerned Hungary which lost two-thirds of the territory it had before the war (...) In a word, the peace was a failure" (Jay Winter, interview with Le Monde, 12.11.2014).

The November 11 1918 armistice was based on a peace that put an end to any form of peace. The First World War marked the entry of capitalism into its decadence and the era opening up led to a semi-permanent state of war. Some examples of the two decades following the signing of the armistice demonstrate this:

- After the end of the war, Greece was awarded a zone of occupation within Turkey. During the summer of 1920, the Greeks wanted to enlarge this zone but they came up against strong resistance by the Turks. This was the beginning of the Greek-Turkish war which lasted up to 1922. The war led to atrocities on both sides as, for example, the massacre of hundreds of thousands of Greeks and Armenians by the Turks. In 1920, the northern Moroccan tribes of the Riff unified and unleashed a war against Spanish domination and during summer, 1921, around 19,000 Spanish soldiers perished. This war against Spain, later supported by France, lasted into 1926 and during it both Spanish and French used asphyxiating gases which caused thousands of deaths.

- In 1929, the Chinese occupied the Manchurian railway which led to a conflict with the Soviet Union. When Russian troops crossed the Chinese frontier on November 15, ferocious fighting broke out, causing the deaths of more than 2000 soldiers with ten thousand wounded. The "Moukden incident" (Manchuria), where the railway line was bombed, probably staged by the Japanese, was used as an excuse for the latter to invade and occupy parts of north-eastern China. In 1937, the war spread through an attack on the whole Chinese subcontinent, the greater part of which was occupied by Japan. During this war hundreds of thousands of Chinese, mostly civilians, were killed with Japanese troops responsible for numerous massacres.

- October 3 1935: Italy unleashed a war against Ethiopia. After seven months of intense fighting it succeeded in conquering the country. In their attacks against the civilian population the Italians used mustard gas on a grand scale. More than 25,000 military personnel were killed in the fighting and the conflict cost the lives of a quarter-of-a-million civilians. In 1936, a number of generals began a war against the Spanish Republic, with the support of Italy, Germany and Portugal. On its side the Republic was supported by the Soviet Union and Mexico. This war, which lasted three years and which ended with a victory for the generals, resulted in more than half-a-million dead. March 12 1938 the Germans returned to Austria and by March 15 they occupied part of Czechoslovakia, while Hungary occupied the other part. These military conquests constituted the first actions which led to the outbreak of the Second World War.

2. The armistice: an attack against the proletarian revolution in reaction to the war

The armistice allowed the bourgeoisie to declare war on the proletariat: (a) by dividing the workers into countries of victors and vanquished and: (b) by turning the armies against the revolution. In Russia the counter-revolution developed with force (cf. "The world bourgeoisie against the October Revolution", International Review no. 160). In Germany as well the bourgeoisie were ready to unleash its counter-revolutionary terror. Eaten up with a fierce hatred of the working class, it prepared to wipe it out with force and exterminate the hotbeds of revolutionary communism.

Divide the working class

The bourgeoisie were conscious of the danger: "all Europe is petrified by the spirit of revolution. There's not only a profound feeling of discontent, but also anger and revolt among the workers (...). All of the existing order, in its political, social and economic aspects, is being called into question by the popular masses from one end of Europe to the other" (Lloyd George, British Prime Minister, in a secret memorandum addressed to the Prime Minister of France, Georges Clemenceau, March 1919). Through the signing of the armistice, the working class in Europe was divided into two parts: on one side the workers who found themselves in the camp of the defeated nations and on the other side those that lived in the victorious capitalist states, who were then submerged by a wave of national chauvinism (above all in France, Britain, Belgium and the USA). In this way the bourgeoisie succeeded in limiting the revolutionary movement of the first group of states (plus Italy).

The situation of Belgium some days after November 11 perfectly illustrates the consequences of this division: German soldiers who were barracked in Brussels and strengthened by detachments of sailors of the Kriegsmarine coming from Ostend, revolted and elected a revolutionary soldier's council. They demonstrated in the streets of Brussels with German, Belgium and red flags and called for the solidarity of the Belgium workers and their organisations. Faced with some fraternisation with members of the Young Socialists, the union organisations rapidly called on workers not to join in, and, under the influence of chauvinist propaganda, the workers in Brussels remained passive and compliantly waited for the triumphal entry of the victorious Belgian army some days later.

The armies aimed against the revolution

"The different national bourgeoisie's tried first of all to grab territories off each other on the battlefields of the imperialist war at a cost of 20 million dead, along with an incalculable number of wounded. But, confronted with a class which fought on its own class ground, they straightaway closed ranks. It confirms, once again, that the dominant class, divided by its own nature, can unite faced with a revolutionary situation in order to confront the working class" ("1918-1919: Seventy years ago - the German revolution", International Review no. 56).

When the soviets took power in October 1917, the reaction of the imperialist forces was immediate. A bourgeoisie, united at the international level, confronted the young soviet republic with armies coming from 21 countries. The counter-revolutionary attack began in 1917 and lasted up to 1922, during which the White Armies unleashed a terrible civil war. The armies of the capitalist states of Europe, the United States and Japan caused an unknown number of casualties in their attacks against the working class in Russia. Among the victims of the civil war there were about one million soldiers of the Red Army killed, and several million people died because of the indirect consequences of the war, such as famine and epidemics. The number of deaths caused by the terror of the White Armies is estimated to be between 300,000 and one million people[1] .

The unfolding of the revolution in Central Europe, Germany, Austria, Hungary, etc., meant that the German army wasn't completely disarmed: "The idea was shared that the German army had to be sufficiently strong in order to maintain domestic order and for preventing a seizure of power by the Bolsheviks" (Lloyd George at war, George H. Hassar). Thus the German High Command, which was demanding 30,000 armed soldiers, was allowed to keep 5,000 machine-gunners.

In Germany the insurrection broke out at the end of 1918. November 10 1918, General Groener, the successor of Ludendorf in charge of the headquarters of the German army, proposed a pact over the telephone to the head of government, the Social Democrat Friedrich Ebert. The general proposed loyal collaboration to quickly put an end to "Bolshevism" and to ensure the restitution of "law and order". "It was a pact against the revolution. 'Ebert accepted my proposition of an alliance' wrote Groener. 'From this moment, we discussed every evening through the means of a secret connection between the Chancellery and the High Command the necessary measures to take. The alliance functioned well'"[2].

Because of the influence of the revolution the bourgeoisie could no longer trust large parts of the land army and sailors. In the perspective of the class war, the Social Democrat Gustav Noske, who re-joined the Ebert government in December 1918, got the job of setting-up the Freikorps. These units brought together loyal professional soldiers, conservatives and ultra-nationalists who wanted to defend their country against Bolshevism and who had found themselves on the margins of society at the end of the war. Thus by January 1919, the German state could once again deploy loyal military units of some hundreds of thousands of soldiers, among which were 38 Freikorps units. In the fight against the revolution, the SPD shamelessly used these most reactionary armed forces against the revolution. By affirming that "someone must play the bloodhound" and denouncing the workers and soldiers in revolt as "the hyenas of the revolution", Noske sent his Freikorps against them: the war against the working class had begun. From mid-January the military attack against the insurgents and revolutionary organisations (parties, groups, press, etc.) began. Entire workers' areas of the large towns were attacked one after the other and terrible massacres were perpetrated everywhere (read the articles on the German revolution on this site).

The war against the working class wasn't only undertaken in Germany but also in other countries. One of these was Hungary where the workers' revolt had also brought to power a revolutionary leadership. Here also the revolt was bloodily wiped out after some months by a military invasion of capitalist forces. On August 1 1919, Romania invaded Hungary and overthrew the revolutionary government. Supported by France, Britain and the White Army, Romanian troops entered Budapest and set up a trade unionist government which liquidated the workers' councils. When the unions had finished their dirty work, they transferred power to one Admiral Horty (later a Nazi collaborator) who instituted a regime of terror against the workers, resulting in 8,000 executions and 100,000 deportations, with Jews particularly targeted.

3. Peace cannot exist within capitalism

Capitalism is violence and peace within capitalism is a complete illusion. The history of the twentieth century demonstrates that an "armistice" is only reached in order to start new wars. While the guns were never silent between World Wars One and Two, the tendency to permanent war became even more evident after the Second World War. Thus the Cold War period wasn't, as is often suggested, one of a "simple" armed peace, but one of dozens of intense armed confrontations (Korea, Vietnam, Africa, the Middle East, etc...) taking place over the whole of the planet and resulting in millions of deaths.

Wishful thinking about peace doesn't prevent war even when supported by massive demonstrations. July 25 1914, the SPD called for a mass demonstration against war. The call was heeded by large numbers: on July 29 and 30, 750,000 people participated in protests throughout Germany. That didn't prevent the bourgeoisie from continuing its course towards war[3]. Quite the contrary, this same social democratic SPD decided some days later to betray the working class and support the bourgeoisie in its war fervour.

A mass mobilisation can be a moment in the resistance against war but it must take place within the framework of a generalised workers' revolt and aimed against the bourgeois state, as in 1917 in Russia. And even in Germany 1918, the revolt's only aim in the first instance was the end of the war. And the war was effectively stopped because a real threat of the workers taking power existed. In fact, only a revolutionary overthrow and the seizure of power by a revolutionary class can eventually put an end to all forms of war.

"Either the bourgeois government makes peace, as it makes war, and then imperialism will continue, as after each war, to dominate and war will be followed by a new rearmament, destruction, reaction and barbarism. Or, you must gather your forces for a revolutionary insurrection, fight in order to take political power which will allow you to impose peace both inside and outside the country" ("Spartacus Letters" no. 4, April 1917, Rosa Luxemburg).

Dennis, 10.11.2018

[1] https://www.quora.com/How-many-people-died-during-the-Russian-Civil-War [5].

[2] Sebastian Haffner, The revolution betrayed:https://openaccess.leidenuniv.nl/bitstream/handle/1887/51018/170627_A%20... [6].

[3] A more recent example was in February 2003 where estimates of the numbers protesting in London against the impending Gulf War run into a million-and-a-half. There were hundreds of thousands more in protest elsewhere in the country and millions more world-wide. Unperturbed, the ruling class continued with its preparations for and execution of the war.

Rubric:

Our comrade Elisabeth has left us

- 432 reads

Our comrade Elisabeth has left us at the age of 77. She died from breathing difficulties which provoked a cardiac arrest, on the night of Saturday/Sunday 18 November.

Elisabeth was born during the Second World War, on 19 May 1941, in Bane, a village in the Jura close to Besançon. Her father owned a saw-mill and a mother was a housewife. Elisabeth grew up in a family of nine children in a rural environment. It was a relatively comfortable Catholic family. Her aunt, a school teacher, provided her primary education before she was sent to a Catholic secondary school run by nuns, in Besançon then in Lyon[1]. She then entered the University of Lyon and developed a passionate interest in oceanography. In 1968, aged 27, she moved to Marseille, renting an old house with a small garden and a terrace on the roof, a few steps from the sea. She was employed by the Centre d’Océanologie of the CNRS[2] in Marseille, after spending a year in Canada. She obtained her PhD in 1983, which enabled her to take on a teaching role and to supervise her students’ research.

Elisabeth was part of that generation of young elements seeking for a revolutionary perspective in the wake of the May 68 movement. She began to be politicised when she was still a student, joining the Parti Socialiste Unifié in Lyon[3].

It was in Marseille that she discovered that the working class was the only force in capitalist society capable of transforming the world. At a demonstration she met Robert, a young element who had been politicised before 1968 in the anarchist movement. She took part in the meetings of the group Informations et Correspondances Ouvrières (ICO) along with Robert, who since 1968 had been publishing Les Cahiers du Communisme de Conseils. In this way Elisabeth discovered the workers’ movement, marxism, and the revolutionary perspective of the proletariat. Having received a Catholic education, she broke with religion and became an atheist, while maintaining very close relations with her family.

In 1972 the group Cahiers du Communisme de Conseils fused with the group that was publishing the review Révolution Internationale. The new group kept the name RI. In 1973 Elisabeth became a sympathiser of RI. In 1974, she joined the group, which would become the section of the ICC in France.

Elisabeth was present at the international conference that founded the ICC in 1975 and the first congress of our organisation in 1976. So with her death a founding member of the ICC, a militant of the first generation, has suddenly left us.

Elisabeth took on important responsibilities in the organisation, always with the utmost dedication. She regularly wrote reports on the international class struggle. She travelled a lot within the ICC and learned Italian in order to be able to participate in the organisation’s work in Italy. She also knew English very well and made many translations, without ever seeing this task as something routine and boring. On the contrary, in translating texts for our internal discussion bulletins Elisabeth was often one of the first French-speaking comrades to be acquainted with the positions and contributions of her English-speaking comrades. And above all, Elisabeth helped establish the ICC’s nucleus in Marseille. For 45 years, alongside another comrade, she maintained the ICC’s political presence in the city.

What animated her militant commitment was her revolt against the barbarity of capitalism, her will to fight against this decadent system, her passion for communism and her conviction in the fundamental role of the revolutionary organisation in the emancipation of the proletariat. Her militant activity was at the centre of her life. Elisabeth had a deep attachment not only to the organisation but also to her comrades in the struggle.

Despite her social status as a CNRS researcher, Elisabeth was extremely modest. She accepted political criticism without ever reacting with wounded pride, always trying to understand and to put forward the general interests of the organisation above her own personal interests. Despite her university degrees, her title as doctor, and her considerable general culture, she was not an “academic”, an “intellectual”, marked by what Lenin, in his book One Step Forward, Two Steps Back, an “aristocratic anarchist”, which is so characteristic of the petty bourgeoisie.

Elisabeth never felt her militant engagement in the ICC as a “prison” or a fetter on the blossoming of her personal life. She did make a career in the university milieu, published scientific books and articles in her sphere of competence, because she had a great deal of knowledge and loved her work. But like Marx and other militants, she chose to devote her life to the cause of the proletariat. We could add that, like all the comrades of the ICC, she had the same conception of happiness as he did: to fight![4]

Thus, at the end of her life, far from being burnt out or crushed by militancy, she showed an astonishing dynamism. Despite her breathing difficulties and her fragile health (in particular since she had fractured her collarbone soon after her last birthday), she participated enthusiastically in a recent ICC weekend of study and discussion. At this meeting she intervened in the debate in a very clear and pertinent way. Before leaving her comrades to go back to Marseille, Elisabeth went with some of them, notably comrades from other countries, to visit the Père Lachaise cemetery and showed the comrades the Mur des Fédérés[5]. This was 15 days before her death.

All the militants of the ICC were thus shocked to receive the tragic news of her sudden death. No comrade imagined that she would be leaving us so soon, without any warning, because she wasn’t so old. Despite her 77 years, she had kept the freshness of youth, and had personal friends from the younger generation.

Elisabeth adored children. One of the great regrets of her life as a woman was that she never had any of her own. This, among other reasons, was why she became friends with the children of comrades who she always welcomed into her home with much affection.

Elisabeth was an extremely warm and welcoming person. She had a deep sense of hospitality. Her old house, in which she had been renting for 45 years, was a place of passage for comrades not only of the section in France but from other territorial sections. They were always welcome, along with their families. She opened her door to all militants of the ICC, without exception. Elisabeth hated private property. When she was away from her house, she always left the key for her comrades (sometimes excusing herself for not having had time to tidy up!).

Elisabeth had her faults of course. But they were the faults of her qualities. She had her own character. Sometimes she would have rows with certain comrades (including those who were closest to her). But she knew how to get over it, always looking for reconciliation because she never lost sight of what united the militants of the ICC: a platform of common principles, the combat which they are all waging against capitalism and the pressure of the dominant ideology. Elisabeth had a deep political esteem for the militants of the ICC, including those whose style or character didn’t suit her. In our internal debates, she listed attentively to all the interventions, all the arguments, often taking her own notes in order to deepen her reflection and, as she put it, “out of a need to clarify”.

Elisabeth was also very sentimental and had a tendency to see the organisation of revolutionaries as a large family or a group of friends. She used to have a certain illusion that the group Révolution Internationale (which she had joined in a period very much stamped by the student movement of May 68) could become a sort of island of communism. What allowed her to overcome this confusion were our days of study and discussion on the circle spirit in the workers’ movement, as well as our internal debates on the difficulties of our section in France, with the aim of moving from “a circle of friends to a political group”[6].

Thanks to her ability to reflect, Elisabeth was able to understand that the organisation of revolutionaries, while being the “beginning of the response” to capitalist social relations, cannot already be the response (to use a term of our comrade MC), a little island of communism within this society. It was her unbreakable commitment to the cause of the working class, her disinterested devotion to the ICC, which allowed Elisabeth to hold on patiently through all the crises the ICC has undergone since its foundation. Despite her “sentimental” approach to the organisation and the pain she felt when certain of her friends deserted it, Elisabeth was never drawn outside the ICC out of a misplaced loyalty to them. Every time she was confronted with a “conflict of loyalties” Elisabeth always decided in favour of the ICC and its struggle for communism (unlike other militants who left the organisation out of loyalty to their friends and with hostility towards the ICC). She never lost her convictions. To the end she remained faithful and loyal to the ICC.

Up until her last breath, Elisabeth was a real fighter for the proletarian cause. A militant who gave the best of herself to the collective and associated work of the main group of the communist left.

Elisabeth loved reading. She loved the sea, flowers, art: baroque music, literature, painting. But above all she loved the human species. Her love for humanity was the backbone of her passion for communism and her militant commitment within the ICC.

The passing of our comrade leaves us with a big hole. For the ICC, every militant is an irreplaceable link in the chain. Elisabeth can’t be replaced, so the only way to fill the hole, to pay homage to her memory, is to continue our combat, her combat.

Elisabeth gave her body to science. She has left us without wreaths or flowers.

To her brother Pierre and all her family;

To her friends Sara and Fayçal who immediately told us of her death;

To her friends in Marseille, Chantal, Dasha, Josette, Margaux, Marie-Jo, Rémi, Sarah…who helped us arranging her house with the greatest respect for her political activities and her final wishes:

We send all our sympathy and solidarity.

Farewell Elisabeth! You departed on a night in November, on your own, which is also a blow to us. But you were not really alone, for all of us you remain alive in our hearts, in our thoughts, in our consciousness.

In January the ICC will organise a meeting of political homage to our comrade. Our readers, sympathisers, fellow travellers, as well as militants of the groups of the communist left who knew Elisabeth, can write to the ICC if they want to take part in this homage which will take place in Marseille.

Révolution Internationale, ICC section in France, 24.11.18

[1] What's more Elisabeth had some very bad memories from her time as a pupil of the "good sisters"

[2] Centre Nationale de Recherche Scientifique

[3] The PSU was formed in 1960 and dissolved in 1989. It was composed of members of the Socialist Party opposed to the latter’s colonialist policies, left wing Christians as well as elements coming from Trotskyism and Maoism. One of its main leaders was Michel Rocard who eventually rejoined the Socialist Party, where he was at the head of its right wing. In the May 68 movement, the PSU took up positions that were much more “radical” than the Communist Party and was in favour of “self-management”

[4] See Karl Marx’s ‘Confession’, https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1865/04/01.htm [7]

[5] The wall where 147 fighters from the Paris Commune were shot and thrown into a trench

[6] This formulation is from a very important contribution to our internal debate written by our comrade MC in 1980. The following extract from it was published as a footnote to our text ‘The question of organisational functioning in the ICC’, International Review 109, https://en.internationalism.org/ir/109_functioning: [8] "In the second half of the 60s, small circles of friends, were constituted by elements for the most part very young with no political experience, living in the student milieu. On the individual level their existence seemed purely accidental. On the objective level - the only one where a real explanation can be found - these circles corresponded to the end of the post-war reconstruction, and the first signs that capitalism was returning to the open phase of its permanent crisis, giving rise to a resurgence of class struggle. Despite what the individuals composing these circles might have thought, imagining that their group was based on friendship, the attempt to realise their daily life together, these circles only survived to the extent that they were politicised, became political groups, and accomplished and assumed their destiny. The circles who didn't become conscious of this were swallowed up and decomposed in the leftist or modernist swamp or disappeared into nature. Such is our own history. And it is not without difficulties that we have survived this process of transformation from a circle of friends into a political group, where unity based on affection, personal sympathy, the same life style, gave way to a political cohesion and a solidarity on a conviction that one is engaged in the same historical combat: the proletarian revolution (...)

Rubric:

The hidden legacy of the left of capital (part one): A false vision of the working class

- 1141 reads

One of the banes affecting revolutionary organisations of the Communist Left is the fact that many of their militants previously went through parties or groups of the left and extreme-left of capital (Socialist and Communist parties, Trotskyism, Maoism, official anarchism, the so-called "New Left" of Syriza or Podemos). That's inevitable given the simple reason that no militant is born with a complete and immediate clarity. However this stage bequeaths a handicap that's difficult to overcome: it's possible to break with the political positions of these organisations (trade unionism, national defence and nationalism, participation in elections, etc.) but it's much more difficult to rid oneself of attitudes, of ways of thinking, ways of debating, behaviours, conceptions which these organisations introduce you to with some force and which constitutes their way of life.

This heritage, which we are calling the hidden legacy of the left of capital, helps to stir up tensions in revolutionary organisations between comrades, provoking mistrust, rivalries, destructive behaviours, blockage of debate, aberrant theoretical positions, etc., which, combined with the pressure of bourgeois and petty bourgeois ideology, can cause these organisation serious damage. The objective of the series we're beginning here is to identify and combat this oppressive weight.

The left of capital: capitalist politics in the name of "socialism".

Since its first congress (1975), the ICC has addressed the problem of organisations that make false claims of "socialism" while practicing capitalist politics. The ICC's Platform, adopted by this congress, put forward in point 13: "All those parties or organisations which today defend, even ‘conditionally’ or ‘critically’, certain states or fractions of the bourgeoisie whether in the name of ‘socialism’, ‘democracy’, ‘anti-fascism’, ‘national independence’, the ‘united front’ or the ‘lesser evil’, which base their politics on the bourgeois electoral game, within the anti-working class activity of trade unionism or in the mystifications of self-management, are agents of capital. In particular, this is true of the Socialist and Communist parties."

Our Platform also concentrates on the problem of groups who put themselves "on the left" of these larger parties, often making "fiery criticisms" of them and adopting more "radical" poses: "All the so-called ‘revolutionary’ currents – such as Maoism which is simply a variant of parties which had definitively gone over to the bourgeoisie, or Trotskyism which, after constituting a proletarian reaction against the betrayal of the Communist Parties was caught up in a similar process of degeneration, or traditional anarchism, which today places itself in the framework of an identical approach by defending a certain number of positions of the SPs and CPs, such as ‘anti-fascist alliances’ – belong to the same camp: the camp of capital. Their lesser influence or their more radical language changes nothing as to the bourgeois basis of their programme, but makes them useful touts or supplements of these parties."

In order to understand the role of the left and extreme left of capital, it's essential to remember that, with the decline of capitalism, the state shows that "the tendency towards state capitalism expresses itself in the increasingly powerful, omnipresent, and systematic control over the whole of social life exerted by the state apparatus, and in particular the executive. On a much greater scale than in the decadence of Rome or feudalism, the state under decadent capitalism has become a monstrous, cold, impersonal machine which has devoured the very substance of civil society"[1]. This nature applies as much to openly dictatorial single party regimes (Stalinism, Nazism, military dictatorships) as to the democratic regimes.

In this framework the political parties are not the representatives of different classes or layers of society but totalitarian instruments of the state whose task is to submit the whole of the population (mainly the working class) to the imperatives of the national capital. They equally become the head of networks of cronyism, pressure groups and spheres of influence which combine political and economic action and become the breeding ground of an inescapable corruption.

In the democratic systems, the political apparatus of the capitalist state is divided into two wings: the right wing linked to the classic factions of the bourgeoisie and responsible for controlling the most backward layers of the population[2], and the left wing (the left with the unions and a series of extreme left organisations) essentially given over to the control and division of the working class and the destruction of its consciousness.

Why did the old workers' parties become the parties of the left of capital?

Organisations of the proletariat are not exempt from degeneration. The pressure of bourgeoisie ideology corrodes from the inside and can lead to an opportunism which, if not fought in time, leads to its betrayal and integration into the capitalist state[3].Opportunism takes this decisive step at the time of crucial historic events in the life of capitalist society: up to now the two key moments have been world imperialist war and proletarian revolution. In the Platform, we try to explain the process which leads to this fatal stage: "This was the case with the Socialist parties when in a period of subjection to the gangrene of opportunism and reformism, most of the main parties were led, at the outbreak of World War I (which marked the death of the 2nd International) to adopt, under the leadership of the social-chauvinist right which from then on was in the camp of the bourgeoisie, the policy of ‘national defence’, and then to oppose openly the post-war revolutionary wave, to the point of playing the role of the proletariat’s executioners, as in Germany 1919. The final integration of each of these parties into their respective bourgeois states took place at different moments in the period which followed the outbreak of World War I, but this process was definitively closed at the beginning of the 1920s, when the last proletarian currents were eliminated from or left their ranks and joined the Communist International.

In the same way, the Communist Parties in their turn passed into the capitalist camp after a similar process of opportunist degeneration. This process, which had already begun during the early 1920s, continued after the death of the Communist International (marked by the adoption in 1928 of the theory of ‘Socialism in one country’), to conclude, despite bitter struggles by the left fractions and after the latter’s exclusion, in these parties’ complete integration into the capitalist state at the beginning of the 1930s with their participation in their respective bourgeoisie’s armament drives and their entry into the ‘popular fronts’. Their active participation in the ‘Resistance’ in World War II, and in the ‘national reconstruction’ that followed it, has confirmed them as faithful agents of national capital and the purest incarnation of the counter-revolution".[4] In the space of 25 years (between 1914 and 1939) the working class first lost the Socialist parties, then, in the 1920's, the Communist parties and finally, from 1939, the groups of the Left Opposition around Trotsky which supported the still more brutal barbarity of the Second World War: "In 1938, the Left Opposition became the Fourth International. It was an opportunist adventure because it wasn't possible to constitute a world party in a situation that was going towards imperialist war and thus a profound defeat of the proletariat. The outcome was disastrous: in 1939-40, the groups of the so-called IV International took a position in favour of world war under the most diverse pretexts: the majority supporting the ‘socialist fatherland’ of Russia, but there was even a minority supporting the France of Petain (itself a satellite of the Nazis).

Against this degeneration of Trotskyist organisations, the last remaining internationalist nuclei reacted: particularly Trotsky's wife and a revolutionary of Spanish origin, Munis. Since then the Trotskyist organisations have become ‘radical’ agents of capital which try to stir up the proletariat with all sorts of ‘revolutionary causes’ which generally correspond to the ‘anti-imperialist’ factions of the bourgeoisie (like the celebrated sergeant Chavez of today). Similarly, they sweep up workers disgusted with the electoral circus by mobilising them to vote in a ‘critical’ fashion for the ‘Socialists’ in order to ’block the way for the right’. Finally they always have great hope of taking over the unions through the means of ‘fighting candidates’".[5]

The working class is capable of generating left fractions within proletarian parties when they begin to be affected by the sickness of opportunism. Thus within the parties of the 2nd International, this role was played by the Bolsheviks, the current of Rosa Luxemburg, Dutch Tribunism, the militants of the Italian abstentionist fraction, etc. The history of the combats undertaken by these fractions is sufficiently well known because their texts and contributions are concretised in the formation of the 3rd International.

And from 1919, the proletarian reaction, faced with difficulties, errors and the subsequent degeneration of the Third International, was expressed by the communist left (Italian, Dutch, German, Russian, etc.) which led (with great difficulties and unfortunately in a very dispersed way) a heroic and determined struggle. Trotsky's Left Opposition appeared later and in a much more incoherent manner. In the 1930's, the gap between the communist left (principally its most coherent group Bilan, representing the Italian Communist Left) and Trotsky's Opposition became more evident. While Bilan saw localised imperialist wars as expressions of a course towards a globalised imperialist war, the Opposition became entangled in ramblings about national liberation and the progressive nature of anti-fascism. While Bilan saw the ideological enrolment for imperialist war and the interests of capital behind the mobilisation of Spanish workers for war between Franco and the Republic, Trotsky saw the 1936 strikes in France and the anti-fascist fight in Spain as the beginning of the revolution... However, what's worse is that even if Bilan wasn't yet clear on the exact nature of the USSR, it was clear to it that it couldn't support it, above all because the USSR was an active agent in preparing for the war. Trotsky on the other hand, with his speculations about the USSR as a "degenerated workers' state", flung the doors wide open for supporting the USSR, which was a means of supporting the second world butchery of 1939-1945.

The role of the extreme left of capital against the resurgence of workers' struggle in 1968

Since 1968, the proletarian struggle took off again across the entire world. May 68 in France, the "Hot Autumn" in Italy, the cordobazo" in Argentina, the Polish October, etc., were among its most significant expressions. This struggle brought up a new generation of revolutionaries. Numerous working class minorities appeared everywhere and all that constituted a fundamental strength for the proletariat.

However, it is important to note the role of groups of the extreme left in the weakening and destruction of these minorities: the Trotskyists whom we have already mentioned, official anarchism[6], and Maoism. Regarding the latter it's important to stress that it's never been a proletarian current. The Maoist groups were born from imperialist conflicts and wars of influence like those between Peking and Moscow which led to the rupture between the two states and the alignment of Peking to American imperialism in 1972.

It's been estimated that towards 1970 there were more than a hundred thousand militants around the world who, although with enormous confusion, pronounced themselves in favour of revolution, against the traditional parties of the left (Socialist and Communist parties), against imperialist war, and looked to advance the proletarian struggle that was breaking out. A striking majority of this important contingent were recuperated by this constellation of groups of the extreme left. The present series of articles will try to demonstrate in some detail all the mechanisms through which they undertake this recuperation. We will talk not only about the capitalist programme printed on their radical and “working class” standards but also their methods of organisation and debate, their mode of functioning and their approach to morality.

What's certain is that their actions have been very important in the destruction of the potential for the working class to build up a wide-scale avant-garde for its struggle. Potential militants have been turned towards activism and immediatism, channelled into sterile combats within the unions, municipalities, electoral campaigns, etc.

The results have been clear:

- The majority have quit the struggle, profoundly frustrated and prone to scepticism towards working class struggle and the possibility of communism; a significant part of this sector fell into drugs, alcohol and the most absolute despair;

- A minority has remained as the core troops of the unions and parties of the left, propagating a sceptical and demoralising vision of the working class;

- Another, more cynical minority, has made careers in the unions and parties of the left and some of these "winners" have become members of parties of the right[7].

Communist militants are a vital asset and it's a central task of the groups of the present communist left, who are the inheritors of Bilan, Internationalisme, etc., to draw all the lessons from this the enormous bloodletting of militant forces that the proletariat has suffered since its historic awakening in 1968.

A false vision of the working class

In order to carry out their dirty work of confinement, division and confusion, the unions, the left and extreme left parties propagate a false vision of the working class. They impregnate communist militants and deform their thoughts, their behaviour and their approach. It is thus vital to indentify and combat this.

1. A sum of individual citizens

For the left and extreme left, the workers do not make up an antagonistic social class within capitalism but are instead a sum of individuals. They are the "lower" part of the "citizenship". As such, all the individual workers can only hope for is a "stable situation", a "fair reward" for their work, "respect for their rights", etc.

This allows the left to hide something that is fundamental: the working class is a class that is indispensable to capitalist society because without its associated labour capitalism couldn't function. But, at the same time, it is a class excluded from society, foreign to all its rules and vital norms; it is thus a class which can only realise itself as such when it abolishes capitalist society from head to toe. Instead of this reality, the left pushes the idea of an "integrated class" which, through reforms and participation in capitalist organisations, can satisfy its interests.

With this overall view the working class is dissolved into an amorphous and inter-classist mass of "citizens" aka "the people". In such a disorder, the worker is assimilated to the petty-bourgeoisie which cons it, to the police which represses it, to the judge who condemns it, to the politicians who lie to it and even to the "progressive bourgeoisie". The idea of social classes and class antagonisms disappears, giving way to notions about the citizens of the nation, to the false "national community".

Once the idea of class is erased from the mind of the working class, the fundamental notion of a historic class also disappears. The proletariat is a historic class which, beyond the situation of different generations or geographical place, has a revolutionary future within its hands, the establishment of a new society which goes beyond and resolves the contradictions which lead capitalism towards the destruction of humanity.

In sweeping away the vital and scientific ideas of social classes, class antagonisms and historic class, the left and extreme left of capital reduce revolution to a pious wish that should be left in the hands of political "experts" and parties. They introduce the idea of the delegation of power, a concept that is perfectly valid for the bourgeoisie but absolutely destructive for the proletariat. In fact the bourgeoisie, an exploiting class which holds economic power, can entrust the management of its business to a specialised political personnel which makes up a bureaucratic layer that has its own interests within the complex needs of the national capital.

But it's not the same for the proletariat which is both an exploited and revolutionary class which has no economic power but whose sole strength is consciousness, unity and solidarity and its confidence in itself. These are all factors that are rapidly destroyed if it relies on a specialised layer of intellectuals and politicians.

Armed with the idea of delegation, the parties of the left and extreme left defend participation in elections as a way of "blocking the road to the right", that's to say that in the ranks of the workers they undermine the autonomous action of a class to turn it into a mass of voting citizens: an individualist mass, each one locked into their "own interests". In this vision, the unity and self-organisation of the proletariat no longer exists.

Lastly, the parties of the left and extreme left also call for the proletariat to place itself in the hands of the state in order to "reach another society". They thus use the trick of presenting the capitalist hangman, the state, as "the friend of the workers" or "its ally".

2. A vulgar materialism that sees only a mass of losers

The left and the unions propagate a vulgar materialist conception of the working class. According to them, workers are individuals who only think of their families, their comforts, a better car or home. Drowned in consumerism, they have no "ideal" of struggle, preferring to stay at home watching football or in the bar with their pals. In order to complete the loop, they affirm that because workers are up to their necks in debt to pay for their consumerism, they are incapable of undertaking the least struggle[8].

With these lessons in moral hypocrisy they transform the workers' struggle, which is a material necessity, into a matter of ideal will, whereas communism - the ultimate aim of the working class - is a material necessity in response to the insoluble contradictions of capitalism[9]. They separate and oppose the immediate struggle from the revolutionary struggle whereas in reality there's a unity between the two since the struggle of the working class is, as Engels said, at once economic, political and a battle of ideas.

To deprive our class of this unity leads to the idealist vision of an "egotist" and "materialist" struggle for economic needs and a "glorious" and "moral" struggle for the "revolution". Such ideas profoundly demoralise the workers who feel shame and guilt at being concerned for their own needs and that of their nearest and dearest, and are made to feel like servile individuals who only think of themselves. With these false approaches, which follow the cynical and hypocritical line of the Catholic Church, the left and extreme left of capital sap the confidence of the workers in themselves as a class and try to present them as the "lowest" part of society.

This attitude converges with the dominant ideology which presents the working class as losers. The famous "common sense" says that workers are individuals who remain workers because they are not good enough for anything else or they haven't worked hard enough to progress up the social scale. The workers are lazy, have no aspirations, don't want to succeed...

It really is the world turned upside-down! The social class which through its associated labour produces the majority of social riches of society is supposed to be made up of its worst elements. Since the proletariat makes up the majority of society, it seems that it is fundamentally composed of cowards, losers, uncultured individuals without any motivation. The bourgeoisie not only exploits the proletariat, it mocks it as well. The minority which lives off the efforts of millions of human beings has the audacity to consider the workers as lazy, useless, unsuccessful and without hope.

Social reality is radically different: in the associated world-wide labour of the proletariat, it develops cultural, scientific and, at the same time, profoundly human links: solidarity, confidence and a critical spirit. They are the force which silently moves society, the source of the development of the productive forces.

The appearance of the working class is that of an insignificant, passive and anonymous mass. This appearance is the result of the contradiction suffered by the working class as an exploited and revolutionary class. On the one hand it's the class of global associated labour and, as such, it is what makes the wheels of capitalist production function and has in its hands the forces and capacities to radically change society. But on the other hand, competition, the market place, the normal life of a society where division and each against all prevails, crush it into a sum of individuals, each one impotent with feelings of failure and guilt, separated from the others, atomised and forced to fight alone for oneself.

The left and extreme left of capital, in complete continuity with the rest of the bourgeoisie, only want us to see an amorphous mass of atomised individuals. In this way they serve capital and the state in their task of demoralising and excluding the class from any social perspective.

We return here what we said at the beginning: the conception of the working class as a sum of individuals. However, the proletariat is a class and acts as such each time it succeeds in freeing itself from the chains which oppress and atomise it with a consistent and autonomous struggle. Thus we not only see a class in action but we also see each one of its components transform itself into active beings, fighting, taking the initiative and developing creativity. We've see it in the great moments of class struggle, as the revolution in Russia of 1905 and 1917. As Rosa Luxemburg underlined so well in The Mass Strike, the Political Party and the Trade Unions: “But in the storm of the revolutionary period even the proletarian is transformed from a provident pater familas demanding support, into a ‘revolutionary romanticist’, for whom even the highest good, life itself, to say nothing of material well-being, possesses but little in comparison with the ideals of the struggle."[10]

As a class, the individual strength of each worker is set free, gets rid of it shackles and develops its human potential. As a sum of individuals, the capacities of each are annihilated, diluted, wasted for humanity. The function of the left and extreme left of capital is to keep the workers in their chains, that's to say, as a mere sum of individuals.