International Review no.37 - 2nd quarter 1984

- 3416 reads

What point has the crisis reached?: The myth of the economic recovery

- 1895 reads

The bourgeoisie is making a lot of noise about a so-called economic ‘recovery’ which is supposed to represent the victory of Reagan’s austerity policies. The OECD begins its report, in Economic Perspectives, December 1983, with an almost triumphant declaration: “The recovery of economic activity now involves almost all the countries of the OECD.” And it highlights a series of positive points: increasing GNP and industrial production, falling inflation, reduction in budget deficits, increasing profits. Two pages later, the OECD writes: “If this appreciation were to prove false, it would be necessary to revise this forecast as to the vigor and duration of the recovery.” ... This kind of remark shows how much confidence the bourgeoisie itself has in the recovery it announces so loudly!

Undeniably, certain economic indicators which were negative in 1982 turned positive in 1983, which means simply that 1983 was less appalling than 1982 -- at least for the bourgeoisie. From this to a real economic recovery there is not a step but a gulf to be leapt. Before analyzing its causes and perspectives, let us briefly examine the reality of this ‘recovery’.

The growth in GNP and industrial production

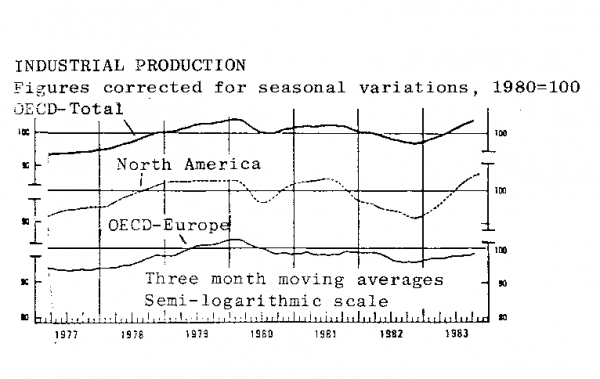

This growth is to all intents and purposes limited to the US and its extent is wretched enough, In the US, the GNP has risen by 3.5%, whereas in Europe it has hardly risen by 1%. Industrial production rose by 6% in the US, which does not even compensate for the fall of 1982 (-8.1%): the balance over two years is still a fall of -2.6%! As for the European countries, the growth in their industrial production is magnificent, varying as it does from ... -4.3% in Italy to 1% in Britain!

Degree of use of the productive forces

Under-utilization of the productive forces is one of the clearest signs of over-production. Despite a 10% increase over 1982, the rate of utilization of productive capacity has not risen above 80% in the US. As for unemployment, contrary to the miracles that were forecast, it has only fallen at an annual rate of 0.2% in the US and continues its rapid advance in all the European countries.

Investment

Company investments have continued to decline, despite the ‘recovery’. Since these investments are the basis for any long-term recovery, this is a sign that the bourgeoisie itself does not believe in the recovery.

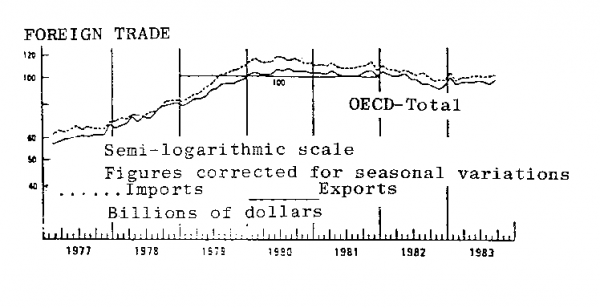

World trade

This remained stagnant in 1983, after a 2% drop in 1982.

Taken as a whole, these figures (drawn from the bourgeoisie’s official statistical body -- the OECD) prove incontestably that, while capitalism may well be pausing briefly in its deepening crisis, there can be no question of a real economic recovery. The only positive development that the bourgeoisie can boast of is a real drop in inflation, and we shall see later just what this drop in inflation really means. The existence of a momentary lull in a general course towards collapse merely expresses the uneven profile that has always characterized the development of the capitalist economy. The important thing is to see whether this development is rising or falling: today, it is pointed firmly downwards, with no perspective of reversing direction.

After the profound recession of 1975, the western bourgeoisie resorted to a massive dose of its classic drug: credit, printing paper money without any economic counterpart. The United States played a primary role here: the multiplication of dollars and its balance of payments deficit did indeed act as a locomotive on the whole world economy. This policy’s failure, in the form of unbridled worldwide inflation, pushed the bourgeoisie to reverse the tendency and develop its monetarist conceptions. History does not repeat itself, and the bourgeoisie today no longer has the means to reproduce the same scenario, since the specter of a collapse in the international monetary system remains ever-present, even without inflation, if only because of colossal state indebtedness, which simply gets worse as the dollar rises. And so, despite the famous ‘recovery’, the US experienced a record number of bank failures in 1983.

The ‘trick’ invented by the American bourgeoisie to stimulate the economy without stimulating inflation consists essentially in transferring capital from one hand to the other. On the one hand, the US, thanks to exceptional interest rates, attracts capital from all over the world, and repatriates the mass of dollars scattered abroad. On the other, the worldwide reduction in wages and rapidly growing productivity allows the bourgeoisie to increase significantly the capital accruing to it in the form of surplus value. This double movement of impoverishment of the proletariat and of other countries relative to the US, gives the latter the necessary resources to finance its budgetary, commercial and current operations deficits. These have grown considerably during the previous year, showing that Reagan’s monetarist language is merely, in the final analysis, a bluff. The federal budget deficit has tripled in two years, from $70 billion in 1981 to $179 billion in 1983; the balance of payments deficit has doubled in one year, from $36 billion in 1982 to $63 billion in 1983; the current operations deficit has quadrupled in one year, from $11 billion to $42 billion.

These astronomical figures, which are nonetheless accompanied by falling inflation and a rising dollar -- apparently in contradiction to all economic logic -- are a good expression of the enormous flow of capital into the US taking place today. At the same time, it reveals the full limits of the present ‘recovery’. In contrast to the end of the ‘70s, the US is no longer up to acting as ‘locomotive’ for the world economy. Although it is once again importing vast quantities of goods, the uplifting effect of pursuing this policy is partially wiped out by the transfer of capital in the same direction, and the increasing cost of raw materials priced in dollars (eg, oil). The improvement of the economic situation in the US, which has nothing spectacular about it as we have seen, is accompanied by a stagnation of the European economies, which is not destined to change qualitatively.

In the longer term, the present mechanism of the US ‘recovery’ heralds a catastrophic future for the world economy. The present over-valuing of the dollar, as a result of the high American interest rates, allows the US to import cheaply, but it undermines the competitiveness of the exporting sector, which further increases the balance of payments deficit. Under the pressure of the law of value, the dollar is bound to devalue, and the whole beautiful machinery at work today will burst like a balloon. At this point, the American budget and balance of payments deficits, which have been left to swell in the most spectacular manner, will no longer be compensated and the inflation presently hidden by high interest rates and the movement of capital will come into the open.

Capitalism will then find itself in a situation ten times worse, and will be hurled ever deeper into the abyss.

ML

Recent and ongoing:

- Economic Crisis [1]

Communists and the National Question, Part 2 (1900-1920): The debate during the years of imperialist war

- 5421 reads

In the first article in this series in International Review 34, we examined the attitude of communists to the national question on the eve of capitalism’s decadent epoch, and in particular the debate between Lenin and Rosa Luxemburg on whether the working class should support ‘the right of nations to self determination’. We concluded that even when some national liberation struggles could still be considered progressive vis a vis the interests of the working class, such a slogan had to be rejected.

With the declaration of war in 1914, a whole new range of questions was posed for the workers’ movement, and in this article we want to look at the first attempts of communists to discuss them, and their implications for the question of support for all nationalist struggles.

One of the specific functions of revolutionaries is always to do their best to analyse the reality which confronts their class. The debate amongst the fractions of the ‘Zimmerwald Left’ during the first imperialist world war on the question of national liberation struggles was a vital part of this concern to delineate the conditions confronting the class struggle; new, unprecedented conditions of global capitalist warfare, unfettered imperialism and massive state control.

Sixty years later the debate is not the same and revolutionaries have no need to repeat its inadequacies or errors. The experience of the class itself has provided answers, as well as new problems. But if today’s political minorities do not adopt for themselves the same spirit of ruthless critique and practical investigation, clinging instead to slogans more appropriate to the ascendant period of capitalism, then they fail in their basic duties and reject the whole methodology of Lenin, Luxemburg and left fractions. It is this methodology which has led the ICC, to reject the position of Lenin on the national question and develop the contribution made by Rosa Luxemburg.

THE NATIONAL QUESTION IN THE ZIMMERWALD LEFT

Those revolutionaries who remained faithful to the spirit of the Communist Manifesto and its rallying call – “The workers have no fatherland. Workers of the world unite!” – regrouped in the Zimmerwald movement of those opposed to the war, but were soon forced to organise themselves as a left-wing within this movement in order to defend a clear class position against the reformist and pacifist tendencies of the majority. The Zimmerwald Left was founded in 1915 on the basis of a recognition:

- of the imperialist nature of the war, against the lie of ‘defence of the fatherland’;

- of the need for a struggle for political Power and the proletarian revolution as the only answer to imperialism;

- that the beginning of this struggle was an active struggle against the war.

While not rejecting the old minimum programme of social democracy and the struggle for reforms within capitalism, this struggle now had to be waged “in order to sharpen in general any social and political crisis of capitalism as well as the crisis caused by the war and to turn this struggle into an onslaught against the fundamental stronghold of capitalism... Under the slogan of socialism this struggle will make the labouring masses impervious to the slogan of the enslavement of one people by another...” (Draft Resolution of the Zimmerwald Left, 1915).

Despite a continuing attachment to the minimum programme, which was appropriate to the ascendant period of capitalism, the positions of the Zimmerwald Left reflected the break in historical period, and in the workers’ movement itself. It could no longer be a straightforward question of the proletariat supporting bourgeois nationalist movements in order to advance the struggle for democracy within the context of a still expanding capitalist mode of production. The proletariat’s attitude to national liberation was now inseparable from the need to struggle against imperialist war and, more generally against imperialist capitalism itself, with the direct aim of creating the conditions for the revolutionary seizure of power by the working class.

Within the Zimmerwald Left, the Bolshevik Party had already clearly expressed the general, historical attitude of revolutionaries to national liberation struggles:

“At the bottom of real nationalist wars ‘such as took place especially in the period between 1789 and 1871 lay a slow and long process of nationalist mass movements of struggle against absolutism and feudalism, of overthrow of national oppression and of the creation of states upon a national foundation as prerequisites for capitalist development.

"The national ideology created by this epoch left deep traces upon the masses of petty bourgeoisie and upon a section of the proletariat. The bourgeois sophists and the betrayers of socialism, who trail behind these sophists, are making use of this at present, in an entirely different, and imperialist epoch, to divide the workers and to divert them from their class problems and the revolutionary struggle against the bourgeoisie.

"The words of the Communist manifesto that “workers have no fatherland” are now truer than ever. Only the international struggle of the proletariat against the bourgeoisie can open to the oppressed masses the road to a better further”. (Resolution on the character of war, adopted at the Berne conference of the Bolshevik Party, 1915).

It is within this framework that the debate between the different fractions of the Zimmerwald Left on the national question took place. This debate, principally between the Western European communists on the one hand and Lenin on the other, initially focussed on whether it was still possible for the proletariat to give its support to ‘the right of nations to self-determination’, much along the lines of the pre-war polemics between Lenin and Rosa Luxemburg, but inevitably widened out to address two more fundamental questions raised by the entry of capitalism into its imperialist, decadent phase:

- Was it still possible for the proletariat to struggle within capitalism for a ‘minimum programme’ of democratic demands (which included the ‘right to self-determination’)?

- Were progressive national wars still possible which allowed the proletariat to give its support to the bourgeoisie?

Whereas Lenin answered emphatically yes to both questions, others like the German, Dutch and Polish Lefts, along with the Kommunist group around Bukharin and Piatakov inside the Bolshevik Party, tentatively began to answer no, rejecting the slogan of self-determination and attempting to elaborate the tasks of the proletariat faced with new conditions of capitalist decadence. It was these fractions, who tended to cohere around the theory of imperialism defended by Rosa Luxemburg, who were most successful in coming to grips with the national question in decadence, against the rearguard actions of Lenin who was loath to give up elements of the obsolete minimum programme which might still play a vital role in the proletarian revolution in Russia and the backward countries of Eastern Europe and Asia.

1. IS IT STILL POSSIBLE TO STRUGGLE FOR ‘DEMOCRACY’?

When Bukharin opposed the right of nations to self-determination as a proletarian tactic at the Berne Conference of the Bolshevik Party in 1915, Lenin was the first to point out that one could not reject one point in the proletariat’s struggle for democracy without calling into question this struggle itself: if self-determination was impossible to achieve in the imperialist epoch, why not all other democratic demands? Lenin posed the problem as how to link the advent of imperialism with the struggle for reforms and democracy, and from this standpoint he denounced Bukharin’s position as “imperialist economism”; that is, a rejection of the need for a political struggle, and therefore a capitulation to imperialism [1] [2].

But Bukharin was not rejecting the need for a political struggle at all, only the equation of this with the struggle for the minimum programme. Bukharin and the Kommunist group posed the problem as the need for the proletariat to make a decisive break with the methods of the past, and to adopt new tactics and slogans corresponding to the need to destroy capitalism through proletarian revolution. Whereas communists were formerly in favour of the struggle for democracy, now they opposed it. As Bukharin more fully expressed it in a later amplification of this position:

“...it is perfectly clear, a priori, that the specific slogans and aims of the movement are wholly dependent on the character of the epoch in which the fighting proletariat has to operate. The past era was one of gathering strength and preparing for revolution. The present era is one of the revolution itself, and this fundamental distinction also gives rise to profound differences in the concrete slogans and aims of the movement. The proletariat needed democracy in the past because it was as yet unable to think about dictatorship in real terms...Democracy was valuable in so far as it helped the proletariat to climb a step higher in its consciousness, but the proletariat was forced to present its class demands in a ‘democratic’ form...But there is no need to make a virtue out of a necessity...the time has come for a direct assault on the capitalist fortress and the suppression of the exploiters...” (The Theory of The Dictatorship of the Proletariat, 1919)

Since the period of progressive bourgeois democracy was now over, and imperialism was inherent to capitalism’s continued existence; it was utopian and reactionary to advance anti-imperialist demands which left capitalist relations intact. The only answer to imperialism was the proletarian revolution:

“Social democracy must not advance ‘minimum’ demands in the realm of present-day foreign policy... any advancement of ‘partial’ tasks, of the ‘liberation of nations’ within the realm of capitalist civilisation, means the diverting of proletarian forces from the actual solution to the problem, and their fusion with the forces of the corresponding national bourgeois groups... The slogan of ‘self-determination of nations’ is first of all utopian (it cannot be realised within the limits of capitalism) and harmful as a slogan which disseminates illusions. In this respect it does not differ at all from the slogans of the courts of arbitration, of disarmament, etc, which presupposes the possibility of so-called ‘peaceful capitalism’ ”. (Theses on the Right of Self-Determination, 1915).

But Bukharin went further in his rejection of the minimum programme in the imperialist epoch, by showing the need for tactics and slogans which expressed the need for the proletariat to destroy the capitalism state. Whereas in ascendant capitalism the state had ensured the general conditions for exploitation by individual capitalist, the imperialist epoch gave rise to a militaristic state machine which directly exploited the proletariat, with a change from individual ownership of capital to collective ownership through unified capitalist structures (in trust, syndicates, etc.) and the fusion of these structures with the state. This tendency towards state capitalism spread from the economy to all areas of social life:

“All these organisations have a tendency to fuse with one another and to become transformed into one organisation of the rulers. This is the newest step of development, and one which has become especially apparent during the war... So there comes into being a single, all-embracing organisation, the modern imperialist pirate state, an omnipotent organisation of bourgeois dominance.... and if only the most advanced states have attained this stage, then each day, and especially each day of war, tends to make this fact general”. (The Imperialist Pirate State, 1915)

The only force which could confront these united forces of the entire bourgeoisie was the mass action of the proletariat. The need of the revolutionary movement in these new conditions was first of all to manifest its fundamental opposition to the state, which implied a rejection of support for any capitalist country. [2] [3]

It was against this broad attack on the minimum programme, and the rejection of self-determination by most of the Western European lefts, that Lenin wrote his Theses on Socialist Revolution and the Right of Nations to Self-Determination in 1916. From the beginning he was forced onto the defensive by the need to avoid objectively supporting reactionary bourgeois democracy and the democratic state. So he had to agree with Bukharin that:

- "The domination of finance capital and of capital in general is not to be abolished by any reforms in the sphere of political democracy; and self-determination belongs wholly and exclusively to that sphere". (Thesis 2);

- "...all the fundamental demands of political democracy are only partially 'practicable' under imperialism, and then in a distorted form and by way of exception (for example, the secession of Norway from Sweden in 1905)". (Ibid) [3] [4];

- the formation of new nations (Poland, India, etc) in the future, he implied, would be the result of "some slight change" in the political and strategic relations between the major imperialist powers.

Lenin's position was also based on a recognition that the nature of the new period demanded a break with the old reformist methods of struggle:

"...these demands must be formulated and put through in a revolutionary and not a reformist manner, going beyond the bounds of bourgeois legality, breaking them down... and drawing the masses into decisive action, extending and intensifying the struggle for every fundamental democratic demand up to a direct proletarian onslaught on the bourgeoisie, i.e. up to the socialist revolution that expropriates the bourgeoisie". (Ibid).

Capitalism and imperialism could only be overthrown through economic revolution. Nevertheless:

"It would be a radical mistake to think that the struggle for democracy was capable of diverting the proletariat from the socialist revolution or of hiding, overshadowing it, etc. On the contrary, in the same way as there can be no victorious socialism that does not practice full democracy, so the proletariat cannot prepare for its victory over the bourgeoisie without an all-round, consistent and revolutionary struggle for democracy". (Ibid).

This is Lenin's whole argument in a nutshell, but in view of the arguments ranged against it at the time, two key questions remained unanswered:

- in the imperialist epoch, in which bourgeois democracy was reactionary, what was the content of this struggle for democracy?

- how could the proletariat avoid, in practice merely propping up the militarist and imperialist state apparatus?

Lenin was undoubtedly aware of these problems, but could not resolve them. Imperialism, he agreed, turned democracy into an illusion - 'aspirations' among the masses; that is, there existed an antagonism between imperialism's denial of democracy and the masses 'striving' for democracy. What this boiled down to in Lenin's position was the continuing need for a struggle by the working class, not to destroy the capitalist state - not yet, at least - but to work within it and to use its institutions to win further democratic reforms: "The marxist solution to the problem of democracy is for the proletariat to utilise all democratic institutions in its class struggle against the bourgeoisie in order to prepare for its overthrow and assure its own victory". (Lenin, Reply to P. Kievsky (Y. Piatakov), 1916).

Before the February revolution, Lenin was united with Kautsky in believing that the marxist attitude towards the state was that the proletariat should capture state power and use it to create socialism. Be criticised Bukharin's position as un-marxist and semi-anarchist, re-affirming that socialists were in favour of using the existing state institutions.

But in the process of formulating his own answer to Bukharin in 1916 he changed his position, returning to Marx's original writings on the need to smash the bourgeois state apparatus, and stressing that the real significance of the appearance of workers' soviets in 1905 was as the specific form of the dictatorship of the proletariat, the alternative to bourgeois state power; his repudiation of Bukharin became instead the pamphlet better known as State and Revolution, which clearly calls for the demolition of the bourgeois state.

However, despite this vital clarification of his attitude to the state, and despite his attitude to the state, and despite his determined practical struggle for the achievement of the call for "All power to the soviets" in October 1917, Lenin never relinquished his theoretical vision of a democratic revolution'. So for example while in his April Theses he concluded that, to the extent that state power had now passed to the bourgeoisie, "the bourgeois-democratic revolution in Russia is completed", he still included in his programme the need for the proletariat to carry out bourgeois-democratic tasks, including self-determination, in the struggle for soviet power. In Bukharin's phrase, his position on the national question remained "pre-state", remaining largely influenced by the conditions confronted by the proletariat in the under-developed capitalist countries, and based on obsolete conceptions more appropriate to the period of ascendant capitalism than imperialist decadence.

2. ARE NATIONAL WARS STILL PROGRESSIVE?

Since the period of national wars embraced a definite historical period - broadly between 1789 and 1871 - the question posed was firstly whether this period was definitively ended with the outbreak of war in 1914, and secondly, given the undoubtedly imperialist and reactionary nature of this war, whether this signified a general and irreversible characteristic of wars in the new period. Again, whereas the European lefts began tentatively to answer yes to both questions, Lenin was reluctant to concede either, despite a large degree of actual agreement.

This whole issue was obviously a vital one for the Zimmerwald Left who in the midst of the imperialist war denounced the bourgeoisie's lies of defending the fatherland and dying for one's country; if some wars could still be pronounced progressive and revolutionary, then the internationalists should instead call on the working class to defend its fatherland in that particular case. As Bukharin pointed out, in the war this had become a class line:

"The most important question of tactics of our time is the question of the so-called defence of the country. For that is exactly where the line of separation is drawn between the entire bourgeois and the entire proletarian world. This word itself contains a deception for it concerns not really the country as such, i.e. its population, but the state organisation..." (The Imperialist Pirate State).

Therefore:

"The task o social democracy at the present time is a propaganda of indifference with respect to the 'fatherland', to the 'nation', etc, which presupposes the posing of the question not at all in a "pro-state" manner... (protests against a state 'disintegration') but on the contrary, posing it in a sharply expressed revolutionary manner with regard to state power and to the entire capitalist system". (Thesis 7, Theses on the Right of Self-Determination, 1915)

Bukharin demonstrated that if the slogan of self-determination was concretely applied (i.e. through granting independence and the right to secede) in the conditions of imperialist war, it became nothing other than a variant of the slogan 'defence of the fatherland', since it would be necessary to materially defend the borders of the newly independent state in the imperialist arena; otherwise what meaning could the demand have in reality? In this way, the internationalist forces of the proletariat would be splintered and their class struggle taken onto a nationalist terrain:

"Hence it follows that in no case and under no circumstances will we support the government of a Great Power which suppresses the uprising and revolt of the oppressed nation; neither will we mobilise the proletarian forces under the slogan 'the right of nations to self-determination'. Our task in this case is to mobilise the forces of the proletariat of both nations (in common with others) under the slogan of a civil, class war for socialism and for a propaganda against a mobilisation of forces under the slogan 'the right of nations...'." (Thesis 8, Ibid).

The German Left, basing itself on the theory of Rosa Luxemburg, who in the Junius Pamphlet had stated that "Today the nation is but a cloak that covers imperialist desires, a battle cry for imperialistic rivalries, the last ideological measure with which the masses can be persuaded to play the role of cannon fodder in imperialist wars", also came out clearly against the idea of progressive national wars in the imperialist epoch:

"In the era of the unleashing of this imperialism, national wars are no longer possible. National interests serve only as the pretext for putting the labouring masses of the people under the domination of their mortal enemy, imperialism." (Theses 5, Theses of the Internationale group on the Tasks of International Social Democracy, 1916)

In his vigorous riposte, Lenin drew back from making such a general conclusion about the nature of the new period:

- the undoubted imperialist character of the world war did not imply that national wars could not still be possible. On the contrary they were both inevitable and progressive;

- while defence of the fatherland was reactionary with regard to a war between rival imperialist powers, in a 'genuine' national war socialists were not at all opposed to called for national defence.

Lenin could not accept that the entry of capitalism into its imperialist phase dictated the reactionary nature of every war, emphasising the need for a concrete assessment of each separate war, and he refused to accept that the obvious imperialist nature of the advanced countries of Europe and America signified a change in the entire capitalist system from which even the backward countries of Asia and Africa could not escape. In the advanced capitalist countries the era of national wars was long over, but in Eastern Europe and the semi-colonial and colonial countries bourgeois revolutions were still underway; here, national liberation struggles against the major imperialist powers were not yet a dead letter, and therefore defence of the fatherland was still progressive in these cases. Furthermore, even in Europe national wars could not be considered impossible (though he implied they were unlikely), on part of small annexed or oppressed nations against the major powers. He posed the hypothetical example of Belgium annexed by Germany in the course of the war to illustrate the need for socialists to support even the 'right' of the 'oppressed' Belgian bourgeoisie to self-determination.

Lenin's reluctance to concede the German Left's more coherent argument on the impossibility of national wars stemmed mainly from his very practical concern not to reject any possible movement or event which could help to precipitate a crisis in the capitalist system which could be exploited by the proletariat.

"The dialectics of history are such that small nations, powerless as an independent factor in the struggle against imperialism play a part as one of the ferments, one of the bacilli, which help the real anti-imperialist force, the socialist proletariat, to make its appearance on the scene... We would be very poor revolutionaries if, in the proletariat's great struggle for socialism, we did not know how to utilise every popular movement against every single disaster imperialism brings in order to intensify and extend the crisis". (The Discussion on Self-Determination Summed Up, 1916)

He was not interested in the fate of nationalist movements in themselves, but only in their ability to weaken the grip of the major imperialist powers in the middle of the world war, and he therefore placed the Irish rebellion of 1916 on the same level as colonial rebellions in Africa and mutinies among colonial troops in India, Singapore, etc. as signs of the deepening crisis of imperialism.

Let us take the concrete example of the Irish nationalist rebellion of 1916 to illustrate some of the dangers in this approach. For Lenin, the rebellion was evidence in support of his position that encouragement for the nationalist aspirations of oppressed nations could only be an active and positive factor in the struggle against imperialism, against others like Radek and Trotsky who argued that it was a hopeless putsch without serious backing which showed, on the contrary, that the era of national liberation struggles was dead. Lenin didn't argue that there was a mass proletarian movement behind the rebellion, which manifested itself as "street fighting by a section of the urban petty bourgeoisie and a section of the workers": the real issue was the class nature of such nationalist revolts vis a vis the proletariat, or to put it another way: did such movements help to strengthen "the real anti-imperialist force, the socialist proletariat" (Lenin) - or the imperialist bourgeoisie?

Lenin dangerously ascribed to such nationalist actions an anti-capitalist potential: despite their reactionary fantasies, he said, "objectively they will attack capital", (Ibid), and the proletariat had only to unite and direct them to advance the process of social revolution. But without going into the whole history of the 'Irish Question', we can briefly say that it provides facts which repudiate this idea.

The Easter Rebellion of 1916 put the seal of nationalism on the class struggle of the Irish proletariat, already weakened by the partial defeat of its pre-war struggles, but actively mobilising workers behind the armed struggle of southern Irish Catholic nationalism. Despite the lack of sympathy among the mass of workers for this desperate military putsch, the subsequent mass terror campaigns of the British state only served to complete their disorientation and drive them into the arms of the reactionary nationalists, resulting in massacre and the systematic sabotage of any last sign of autonomous class struggle against capital by both British 'Black and Tans' and republican IRA. This defeat of a relatively weakened and isolated sector of the world proletariat by the combined forces of the Irish and British bourgeoisies could only represent the strengthening of world imperialism, whose primary interest is always the defeat of its mortal class enemy. The Irish rebellion only proved that all factions of the bourgeoisie, even in the so-called oppressed nations, side with imperialism when faced with the threat of the destruction of the exploiting system they all rely on for their privileges.

With the benefit of hindsight, revolutionaries today can only conclude that history has proved Lenin wrong, and the lefts, despite their confusions, were essentially right. The lesson of the Irish rebellion is that support for nationalism leads directly to the sub-ordination of the class struggle to the wars of imperialism in the decadent epoch of capitalism.

LENIN AGAINST THE 'LENINISTS'

Lenin's exhortation to support all nationalist revolts has inevitably been exploited by the bourgeoisie as an excuse to drown workers and peasants in countless bloodbaths under the banners of nationalism and 'anti-imperialism'. However, a river of blood still separates the worst of Lenin's errors from the 'best' position defended by those Stalinist, Trotskyist and Maoist butchers of the proletariat who proclaim themselves his true heirs. It is also necessary to rescue the original critical content of Lenin's writings from those like the Bordigists of the ICP (Communist Program) and others who, while remaining within the revolutionary camp, prefer also to remain attached to all the errors of the past even when they lead dangerously close to defending the most reactionary capitalist factions in the name of 'national liberation' (see IR 32 for a fuller treatment of the ICP's errors and recent decomposition).

Lenin was always aware of the dangers of revolutionaries supporting nationalism and constantly emphasised the need for the proletariat to maintain its unity and independence from all forces of the bourgeoisie; - even though this only tended to make his position even more unworkable and contradictory in practice. So even where he called on revolutionaries to support every revolt against imperialism, he added "provided it is not the revolt of a reactionary class". What the lefts like Rosa Luxemburg were arguing more coherently was that the nationalist element in all revolts against the bloody repression of the major imperialist powers was always injected by the most reactionary class - the bourgeoisie - to stifle the threat of real class revolt; revolutionaries had to draw a clear dividing line between nationalism and the class struggle, since only the latter in the imperialist epoch represented the progressive way forward for humanity.

All along the line, Lenin qualified his position in order to avoid the ever present danger of subordinating the class struggle to the national struggle, whether through capitulating to the democratic state machine or to the bourgeoisie in 'oppressed' nations. The marxist attitude to the national question had always recognised the primacy of the class struggle:

"Unlike the petty bourgeois democrats, Marx regarded all democratic demands without exception, not as absolutes, but as the historical expression of the struggle of the masses of the people led by the bourgeoisie against feudalism. There is not a single one of these demands that could not serve and did not serve in certain circumstances as an instrument in the hands of the bourgeoisie to deceive the workers. In this respect to select one of these demands, namely, the self-determination of nations, and to contrast it with the rest is radically wrong theoretically. In practice, the proletariat can preserve its own independence only if it sub-ordinates its struggle for all democratic demands not even excluding the demand for a republic, to its revolutionary struggle for the overthrow of the bourgeoisie". (Thesis 5, 1916).

Following on from this, Lenin had to codify his position on self-determination concretely to express this need to defend the international unity of the working class and to reconcile this paramount concern of revolutionaries with his theoretical division of the proletariat into two camps - in the 'oppressed' and the 'oppressor' nations. This, for him, was "the most difficult and most important task". So while the proletariat of the 'oppressor' nation must demand freedom of separation for the colonies and small nations oppressed by its 'own' imperialism.

"...the socialists of the oppressed nations must, in particular, defend and implement the full and unconditional unity, including organisational unity, of the workers of the oppressed nation and those of the oppressor nation. Without this it is impossible to defend the independent policy of the proletariat and their class solidarity with the proletariat of other countries in the face of all manner of intrigues, treachery and trickery on the part of the bourgeoisie". (Thesis 4, our emphasis).

How many times do we hear this quoted by today's 'Leninist' enthusiasts for national liberation struggles? Lenin was quite explicit: in the absence of the class unity of the proletariat, including its concrete organisational expression, the working class was unable to defend its autonomy from the enemy class. The class struggle will be subordinated to the national struggle, which in reality is only the struggle of imperialism for a slice of the world market, and the workers will become the cannon fodder for their own bourgeoisie in this struggle. In effect, the watchwords of the Communist Manifesto, "Workers have no fatherland, workers of the world unite!" would be turned on their head: "Workers of all so-called oppressed countries defend your fatherland!"

It is this reciprocal element in Lenin's position on support for self-determination that today's leftists ignore or conceal, but it is central to a defence of proletariat internationalism since it still, in however distorted and practical a way, holds a vision of the global interests of the working class.

Elsewhere in his writings, Lenin firmly rejected an abstract or uncritical approach to the support of nationalist movements: “no democratic demand can fail to give rise to abuses, unless the specific is subordinated to the general; we are not obliged to support either ‘any’ struggle for independence or ‘any’ republican or anti-clerical movement”. (The Discussion Summed Up). The general interests of the class struggle could be contradicted by support for this or that nationalist movement : “It is possible that the republican movement in one country may be merely an instrument of the clerical or financial-monarchist intrigues of other countries; if so, we must not support this particular, concrete movement..." (Ibid).

And from the example of Marx’s refusal to support Czech nationalism in the nineteenth century, Lenin drew the conclusion that if the proletarian revolution should break out in a few larger European countries, revolutionaries should be in favour of a ‘revolutionary war’ against those other capitalist nations which acted as the bulwarks of reaction: i.e. in favour of crushing them and all their outposts no matter what national liberation struggles might arise within their borders.

Whereas for Lenin there was a possibility of nationalist movements acting as weapons of the imperialist powers against the class struggle, for Luxemburg and Bukharin this was a generalised and inevitable phenomenon of the imperialist phase of capitalism. Without having the advantage of their coherent theoretical starting point, Lenin was still forced by the weight of argument to at least lean towards their positions – significantly, he was now forced to admit that the slogan of Polish independence was utopian and reactionary in contemporary conditions, going so far as to say that “...even a revolution in Poland alone would change nothing and would only divert the attention of the masses in Poland from the main thing – the connection between their struggle and that of the Russian and German proletariat”. (The Discussion Summed Up). But he still refused to draw any general conclusion from this ‘specific’ example.

SOME CONCLUSIONS ON THE DEBATE IN THE ZIMMERWALD LEFT

Besides their basic method, one thing all the participants in the debate in the Zimmerwald Left were agreed on, one thing which is so often ignored or paid lip service to in discussions about the possibility of supporting national movements : only the working class struggle offers any future for the oppressed masses of humanity. Nowhere, even in Lenin’s most confused statements on this subject, is there a suggestion that decadent capitalism could be destroyed in any other way except through violent proletarian revolution. The concern which animated Lenin, Bukharin, Luxemburg and the others was whether, and to what extent, national struggles could contribute to bringing about the final crisis of capitalism and thus act in favour of the revolutionary struggle by helping to weaken the whole rotting edifice of imperialism.

Despite the overwhelming agreement on the basic framework of the debate, a sizeable part of the workers’ movement still felt that a complete break with past theory and practice on this question was not yet justified; to Lenin it seemed that workers had nothing to lose by supporting nationalist movements because they were all moving in the same direction towards the destruction of capitalism. Today we have more than enough evidence, in the countless, massacres of workers by nationalist factions, to make our own vital contribution to this debate by concluding that the class struggle and nationalism in all its forms are at no point whatsoever convergent: the latter is always a weapon in the enemy’s hands against the former.

Those revolutionaries who bravely, in a hesitant manner, suggested that the time had indeed come to make a clean break with the past, were in the vanguard of the proletariat’s attempt to understand the world it lived and fought in. Their contribution and in particular the theory of Rosa Luxemburg on the whole question of imperialism and the mortal crisis of capitalism is still an essential cornerstone of the work of revolutionaries in the decadent epoch.

As for Lenin’s position on the national question, it has, as we all know, been pillaged by the bourgeoisie in order to justify all manner of reactionary wars of ‘national liberation’. Nor is it an accident that the left of capital, in search of marxist credentials for its participation in imperialist wars, chose to regurgitate Lenin’s writings, which contain enough dangerous weaknesses to allow a back door to remain open to what has now become one of the cornerstones of the bourgeoisie’s ideology.

True, Lenin cannot be held responsible for the way in which the bourgeoisie, in the wake of the defeat of the proletarian revolution he fought so hard for, has distorted his words. Against the anarchists and libertarians, for whom Lenin was always a bourgeois politician using marxism only to justify his own struggle for power, we can point to the way in which the bourgeois counter-revolution has been forced to pervert the whole framework of the debate in which Lenin participated, and to conceal or suppress certain vital principles he defended in order to rob his contribution of its revolutionary marxist content.

But having said this, unlike the Bordigists, we have no need to remain blind to the errors of the past. From many of the above points, we can see that dangerous weaknesses and ambiguities were present in Lenin’s writings at the beginning which have to be decisively rejected in order to defend clear class positions today.

In a forthcoming article we will examine the tragic practical consequences of the Bolsheviks’ incomprehensions about the national question after October 1917, through the policies of the soviet state.

S. Ray

Part 1: The debate on the national question at the dawn of decadence [5]

Part 3: The debate during the revolutionary wave and the lessons for today [6]

[1] [7] Some of Lenin’s other arguments against the lefts’ position were, it has to be said, pretty feeble. Thus, Bukharin and Piatakov had been “depressed” by the war(!), while the origin of the Dutch and Polish Lefts’ opposition to self-determination was to be found in the histories of their respective small nations; which didn’t quite explain why it was the dominant position taken up by the western European fractions of the Zimmerwald Left at this time, including the German Left.

[2] [8] Bukharin’s position on the smashing of bourgeois state power and his emphasis on the mass action of the workers was in part assimilated from the work of Pannekoek and the German Left, with whom the exiled Kommunist group collaborated during the war. In his pre-war polemic with Kautsky, Pannekoek had emphasised that “the proletarian battle is not just a battle against the bourgeoisie for state power; it is also battle against state power”. (Mass Action and Revolution, 1911). The proletariat’s response to the bloody repression of the bourgeois state was the mass strike.

[3] [9] It should be pointed out that the secession of Norway from Sweden in 1905 was the only concrete example Lenin could ever point to in support of his ‘self-determination’ policy, which is why it keeps popping up in all his writings on the subject. Without delving too deeply, we can say that it contained enough specificity to make it a fragile enough basis for a general position: it occurred on the eve of capitalism’s decadence, in a region outside the major European capitalist heartlands, in a country with a relatively small proletariat. In addition, the Norwegian bourgeoisie had always enjoyed a large degree of political autonomy and, ultimately its formal independence was achieved because the Swedish bourgeoisie were quite prepared to accept it, which is why they allowed a referendum on it in the first place...

Deepen:

Heritage of the Communist Left:

Debate: On the critique of the theory of the "weakest link"

- 3981 reads

Following the defeat and the repression suffered by the working class in Poland in December 81, a discussion began in the ICC with the aim of drawing the maximum number of lessons from this experience. The main questions were:

-- why and how had the world bourgeoisie managed to isolate the workers in Poland from their class brothers in other countries?

-- why, in Poland itself, had the workers - who in August 80 had shown such combativity, such a capacity for self-organization, who had shown such intelligence in using the weapon of the mass strike against the bourgeoisie - then fallen so easily into the traps laid by Solidarnosc, which delivered them bound and gagged to the forces of repression?

-- for the world proletariat, what was the true extent of the defeat suffered in Poland? Was it a partial defeat with a relatively limited impact, or a decisive defeat which meant that the bourgeoisie now had a free hand to impose its own response to the inexorable of the economic crisis: generalized imperialist war?

The ICC's International Review no 29 put forward answers to these questions in the article ‘After the repression in Poland: perspectives for the world-wide class struggle.' However, the ICC's thinking didn't restrict itself to the elements contained in this text. It led it to make a more precise critique of the thesis, sketched out by Lenin and developed by his epigones, that the communist revolution would begin, not in the main bastions of the bourgeois world, but in the less developed countries: the ‘capitalist chain' would have to be broken at its ‘weakest link'. This approach led to the publication in IR 31 of a text whose title was a good summary of the thesis defended in it: "The proletariat of western Europe at the centre of the generalization of the class struggle: critique of the theory of the ‘weakest link'".

It also led in January ‘83 to the adoption by the central organ of the ICC of a ‘Resolution on the critique of the theory of the weak link,' and, in July 83 to the adoption by the 5th Congress of the ICC of a ‘Resolution on the International Situation' which affirms that:

"The other major lesson of these battles (in Poland 1980-81) and their defeat is that this world-wide generalization of struggles can only begin from the countries that constitute the economic heart of capitalism. That is, the advanced countries of the west and, among these, those in which the working class has the oldest and most complete experience: Western Europe...If the decisive act of the revolution will be played out when the working class has dealt with the two military giants of east and west, its first act will necessarily be played out in the historic heart of capitalism and of the proletariat: western Europe." (IR 35)

The whole ICC agreed on the necessity to criticize the thesis of the ‘weakest link', which the degenerating Communist International turned into a dogma and which served to justify the worst bourgeois aberrations, notably that of ‘socialism in one country'.

However, a minority of comrades rejected the idea that "the proletariat of western Europe would be at the centre of the world wide generalization of the class struggle," that "the epicenter of the coming revolutionary earthquake would be in this region of the world."

"To the extent that the debates going on in the organization generally concern the whole proletariat they should be expressed publicly" (‘Report on the Structure and Functioning of the Revolutionary Organization', IR 33). We are therefore publishing here a discussion text written by a comrade of the minority and which to some degree synthesizes the disagreements which arose during the course of the debates on this particular question.

Since this text refers to the resolution of January ‘83, we felt that it would be useful to precede it with this resolution even though it was not written for external publication but in order to take a position on the internal debate. This is why the language may be somewhat difficult to follow for the reader who is not familiar with our analyses, and we recommend a prior reading of the texts from IR 29 and 31 already mentioned.

Finally, apart from the resolution and the discussion text, we publish the ICC's response to the arguments contained in the latter.

-------------------------------------------------

Resolution of the ICC

1. The ICC reaffirms the unity of the conditions for the proletarian revolution on a world scale. The unification of the capitalist world in the period of decadence implies that it is the entire world - whatever the degree of development of the countries that compose it - which is ripe for the communist revolution, the conditions for which have existed since 1914 on a world scale. It rejects the Bordigist theory of bourgeois revolutions in certain geographical areas of the Third World, which are presented as a necessary stage towards the proletarian revolution. The latter is not only necessary but possible for each sector of the world proletariat, for whom it is the only perspective faced with the general crisis of the system.

2. Just as the unity of the conditions for the revolution is not the sum of particular national conditions, so the world proletariat is not the sum of its parts. The marxist conception of the revolution is not a vulgar materialist one. The revolution is a dynamic process, not a static one; its forward movement implies going beyond particular geo-historic conditions. This is why the ICC rejects both the ‘theory of the weakest link of capitalism' and the theory of the ‘west European revolution'.

The first, elaborated by the Communist International in its phase of decline, implicitly affirmed that the proletariat of the backward countries could play a more revolutionary role than that of the developed countries (because of the absence of a ‘workers' aristocracy', the non-existence of the poison of ‘democracy', the weakness of the national bourgeoisie). The second, developed in Gorter's Reply to Lenin, put forward the idea that only the proletariat of Western Europe and North America were capable of realizing the world revolution, which was in fact restricted to Western Europe, which had the most favorable objective conditions (strong concentrations of workers, traditions of struggle).

The symmetrical error of these two conceptions had its origins both in the conditions of the time (the 1917 revolution was born out of a war in the periphery of industrial Europe, in a capitalist world still divided into a constellation of imperialisms and of private capitals) and in a confusion between the field of extension and the dynamic of the revolution. In seeking to determine the most favorable objective conditions for the outbreak of the revolution, the revolutionaries of the time had a tendency to confuse the point of departure with the point of arrival of the whole dynamic process of the extension of the revolution.

Although both theories were not bourgeois conceptions and expressed the life of the revolutionary movement of the time as it searched for a coherent view, they have led to the worst kinds of aberrations: the theory of the weak link has ended up in third worldism; the theory of the west European revolution in neo-Menshevism.

3. The mass strike of August ‘80, limited to Poland, does not challenge the classic schema of the international generalization of the class struggle as the qualitative leap needed for the opening-up of a revolutionary period.

Poland posed very sharply the question of the objective conditions most favorable to the development of the international dynamic of the mass strike:

-- in contrast to 1917-18, the bourgeoisie is much better prepared and more united internationally to stifle any threat of generalization beyond the borders of one country;

-- a revolutionary process cannot begin in one country in the absence of a dynamic towards breaking out of the national framework; within national confines, the mass strike can only be smothered.

4. Determining the point of departure for this dynamic, and thus the best conditions for the beginning of the revolutionary earthquake does not mean denying the unity of the world proletariat. It is the very process by which this potential unity becomes a real one.

However, unity does not mean the identity of parts which remain subjected to different material conditions. There is no natural equality between the various organs, the heart and the brain of a living body; they carry out vital, complementary functions.

5. The ICC rejects the naively egalitarian conception which holds that any country can be the point of departure for the revolutionary dynamic. This conception is based on the anarchist belief that, given the example of the revolutionary general strike, all countries could simultaneously initiate a revolutionary process.

In reality, the uneven development of capitalism, by creating an ever-widening gulf between the big industrial countries concentrating the majority of the modern industrial proletariat, and the Third World countries, has the consequence that the most favorable conditions for the birth of the revolutionary framework are strictly determined by the historic and social framework.

6. The point of departure for the world revolution is necessarily to be found in Western Europe, where the force of numbers is supplemented by a revolutionary tradition that goes from 1848 to the first revolutionary wave, where the working class has most directly confronted the counter-revolution and which constitutes the final battlefield for a generalized imperialist war.

Because Western Europe is:

-- the first economic power and the biggest concentration of workers, where the existence of a number of nations next to each other poses the immediate question of going beyond national boundaries;

-- at the heart of the contradictions of capitalism in crisis, contradictions that are pushing it towards world war;

-- the Gordian knot of the most powerful bourgeois mystifications (democracy, parliament, trade unions) , mystifications that the proletariat will have to settle scores with in order to make a liberating leap for the whole world working class.

It is at the very heart of the course towards revolution. The fact that the period of counterrevolution came to an end with May ‘68, the maturation of proletarian consciousness in Europe in the 1970s, the existence of a developed proletarian political milieu: all these factors confirm this point.

7. Neither the countries of the Third World, nor of the eastern bloc, nor North America, nor Japan can be the point of departure for the process that leads to revolution:

-- the countries of the Third World because of the numerical weakness of the proletariat and the weight of nationalist illusions;

-- Japan and especially the US because they have not so directly been through the counter-revolution and world war, and because of the absence of a deep revolutionary tradition;

-- the eastern bloc countries because of their relative economic backwardness and the specific form that the world crisis takes there (scarcity) obstructing the development of a direct and global consciousness of the cause of the crisis (ie overproduction), and because of the Stalinist counter-revolution which has, in the minds of workers, transformed the idea of socialism into its opposite and has allowed democratic, trade unionist and nationalist illusions to have a new impact.

8. However, while the point of departure for the world revolution is necessarily to be found in western Europe, the triumph of the world revolution in the last instance depends on its rapid and victorious extension to the USA and the USSR, the heads of the two imperialist blocs, where the last great act of the revolution will be played out.

During the first revolutionary wave, the countries which had the most advanced and concentrated proletariat were at the same time the most powerful and decisive military countries, ie the countries of Western Europe. Although the most advanced and concentrated battalions of the proletariat are in Western Europe, the centers of world capital's military power have shifted to the USA and the USSR, which has consequences for the development of a revolutionary proletarian movement.

Today, a new anti-working class Holy Alliance between Russian and American capital, going over and above their imperialist rivalries, would lead to a direct military intervention against revolutionary Europe, ie to a world-wide civil war; and the outcome of this would depend on the capacity of the proletariat in the two bloc leaders, especially the USA, to paralyze and overthrow the bourgeois state.

9. The ICC warns against a certain number of dangerous confusions:

-- the idea that ‘anything is possible at any moment, in any place', as soon as sharp class confrontations arise at the peripheries of capitalism; this idea is based on an identification between combativity and the maturation of class consciousness;

-- the unconscious assimilation between the international mass strike and the revolution; whereas international generalization is a qualitative step which announces the revolution; it is the beginning of a revolutionary period but cannot be mixed up with the revolution itself. The latter will necessarily take the form of a situation of dual power which will pose the alternative: dictatorship of the workers' councils or bloody counter-revolution, opening the course towards war;

-- the conception of a linear development of the internationalization of the mass strike, whereas the latter will necessarily follow a winding course, with advances and retreats, as in the example of Poland.

It is up to revolutionaries to keep a cool head and not to give in to immediatist exaltation, which leads to adventurism, or to become depressed and demoralized with each retreat.

Although history has been accelerating since August 1980 and is providing revolutionaries with an exalted perspective, they must understand that their work remains a long-term one.

-------------------------------------------

Critique of some positions of the ICC on the theory of the "weak link"

The last two years have put the capacities of revolutionary minorities to the test. The sudden deepening of the crisis in the entire world, the brutality of the austerity measures the bourgeoisie has taken, the clarity of the massive war preparations, all this seemed to demand a thundering answer from the world proletariat. And yet the working class has suffered an important defeat in Poland while elsewhere on the globe the struggle has stagnated. Revolutionary organizations have remained tiny and without much of an echo. This situation has exposed the many weaknesses which existed in the revolutionary milieu. The confusion is considerable and understandable. Revolutionaries can no longer limit themselves to the reaffirmation of lessons from the past. They have to assess and explain the defeat in Poland and the present difficulties. They have to clarify the perspectives for the workers' struggle, explain how we can get from here to there. In this context, the ICC has formulated its ‘critique of the theory of the weak link'. (‘The Proletariat of Western Europe at the Centre of the Generalization of the Class Struggle', IR 31, ‘Resolution on the Critique of the Theory of the Weak Link', in this issue). Those texts justly reject Lenin's position about a breakdown of the capitalist system starting in the weakest countries and spreading from there to the rest of the system. This theory has been an instrument for those who look for capitalism's gravedigger outside the proletariat. The problem with the ‘Leninists' who defend this position today is not that they have illusions about the strength of the workers in the weak countries, they just have illusions about those weak countries themselves. For them, the proletariat is no more than cannon-fodder for the ‘anti-imperialist movement'.

But the ICC texts go beyond the rejection of this disastrous theory. They explain the defeat in Poland precisely as a result of the fact that Poland is a weaker country and state that "only in Western Europe ... can there be a full development of the political consciousness which is indispensible for (the proletariat's) struggle for revolution". (IR 31, p.7). There it will not be feasible for the bourgeoisie to isolate a mass strike because it will be "no longer possible to set up an economic cordon sanitaire and a political cordon sanitaire will have no more effect." (idem, p 6-7)

This vision certainly gives a way to digest the defeat in Poland and to see more clearly a way ahead. But at the same time:

-- It obscures some of the lessons of Poland and other struggles that occurred and will occur outside Western Europe. It sees their relevance necessarily as limited, since they take place outside the area where the main capitalist mystifications - in the ICC's view - can be overcome;

-- It creates the false impression that the ability of the bourgeoisie to isolate a mass strike depends on the place where it occurs, so that a mass strike in Western Europe would not encounter the same problems as in Poland or would overcome them more easily;

-- It gives the false hope that revolutionary consciousness can come to fruition in Western Europe alone and then break down the capitalist mystifications in other industrialized areas through the power of example ("When the proletariat of these countries detaches itself from the most sophisticated traps laid by the bourgeoisie...the chimes will ring for the world-wide generalization of proletarian struggle, for the revolutionary confrontation" idem, p.8).

Class forces and class consciousness

The proletarian struggle begins out of necessity, not out of consciousness. Mystifications can only be overcome because of and in the struggle. It is the potential of the struggle to grow which enables the working class to break through capitalist mystifications, rather than the other way around. Struggles develop despite the weight of many illusions which all have in common the belief that an improvement in living conditions, a victory, can only be gained within this framework of capitalism. This framework has many names and is colored by local specificities, but it is always the framework of the nation-state.

This illusion still handicaps the workers' struggle in all countries. But it has a very different effect in countries where the proletariat is only a tiny minority dwarfed by other classes as opposed to those countries where the proletariat has the potential power to paralyze the entire economy and smash the bourgeois-state, provided that it only had to confront its ‘own' bourgeoisie.

In the first case, this illusion tends to lure the workers away from their class terrain and into a front with a faction of the bourgeoisie (the Church, the left, the guerillas, ‘progressive' military, etc) because their own potential power within the nation-framework is so small. That's why the workers in those countries need the demonstration of power of the class in the industrialized countries to find the path of autonomous struggle, to follow it in a way that goes beyond mere desperation.

It is only in the second case that this illusion of change within the nation, foundation of all capitalist mystifications, cannot prevent the development of working class struggle on its own terrain. Here, the workers are strong enough to count on themselves, even if they still see themselves only as a social category exerting pressure within the nation and not yet as the world class that has humanity's fate in its hands. Thus it is the key development of the workers' struggle in these countries which is the key to the growing awareness of the entire working class of its own power. And it is this growing awareness of the entire working class which makes it possible for the proletariat to break through the network of capitalist mystifications. Therefore, the major concentrations of the proletariat in the industrial heartlands of both blocs play the decisive role in the development of revolutionary class consciousness. Only there can the struggle grow despite the weight of bourgeois ideology and become the lever by which proletarian consciousness is freed from the weight of the ideology of the dominant class.

But the existence of struggle is in itself not enough. As Marx said, just as a man doesn't throw away the tool that keeps him alive before it has become totally useless and he has found something else to replace it with, in the same way, the proletariat will not destroy the existing social system before the necessity and the possibility of this historical task becomes embedded in its consciousness. And this process is not possible within the limits of Western Europe alone.

Becoming conscious of the necessity of generalization

In order to understand the necessity of revolution, the working class must be able to perceive the destruction of the objective basis of capitalist mystifications. All these mystifications are based on the belief that a prosperous economy within the framework of the nation is possible. In order to destroy this hope for all workers, its falseness must be clearly demonstrated for the whole world, not in the weakest economies, but in the strongest capitalist nations. As long as in these stronger economies a strong illusion in substantial recovery is kept alive, the belief that the capitalist nation can be a framework for survival will be kept alive among the workers in all countries, weak or strong. That implies that the revolution is not for next year. Talking about a revolutionary assault in the short-term, as some people did during the mass strike in Poland, can only lead to demoralization. But it means also that for the first time in history, this essential condition for worldwide revolution will really be fulfilled. All previous revolutionary attempts of the proletariat have broken their backs on this problem. The mobilization of the workers for the First World War and later the defeat of the first revolutionary wave, were to a large extent made possible by the limits of the capitalist crisis, by the promise of recovery in the stronger countries. The mobilization of workers for the Second World War, their defeat in countries like Spain, was made possible not only by the weight of the defeat of the first revolutionary wave but also by the ability of capitalism to offer new hope for recovery through the launching of state-capitalism on an unprecedented scale (in Germany, for example, industrial production rose 90% between 1933-38, while unemployment declined from 3.7 million to 200,000).

Today capitalism is for the first time approaching the point where it will no longer have any objective economic means to keep alive any hope for recovery, to create a temporary improvement in the situation of ‘its' workers, even in a limited part of the globe. State capitalism has already been developed, not to its theoretical maximum, but to its maximum efficiency. The extension of state capitalism on an international scale, and the redistribution of surplus value it allows through government aid the IMF, world bank, etc, still could be developed some more, but not by much because the foundations of the system - competition - puts an iron limit on this development. This extension has already been fully used during the post-war period to create the markets required by the high development of productive forces in the strongest countries, forging an unprecedented interdependency of all units of the capitalist machine.

As a result, none of them still has the means to shield itself from the crisis. Even attempting to do so would only aggravate its situation. For the first time, a steep decline without a creditable hope for recovery becomes unavoidable for all countries. That doesn't mean that the situation of each country becomes the same, that workers everywhere will be thrown into famine. It means some will be thrown into famine and others into barbaric exploitation, militarization, terror, competition between them and finally into war and global destruction, unless they can prevent it. The specific situations of all workers will not become the same; a myriad of differences will continue to exist. What will be the same everywhere is the all out attack of the bourgeoisie, the interests of the workers, the perspectives they have.

Becoming conscious of the possibility

But to become the conscious goal of their struggle, the workers must not only see the revolution as necessary, but also as possible - within the limits of their forces. The level of political consciousness is necessarily limited by the forces they have at their disposal. A struggle beginning on a platform of limited, economic demands can only expand its goal; can only become political, to the degree that the class forces at the workers' disposal grow accordingly - through extension and self-organization. But what is possible depends also upon the opposition the workers have to overcome. And here again we see important differences between the situation in 1917 and today. In 1917, the bourgeoisie was divided and disorganized by the war, disorientated by its lack of experience. Under these circumstances, there were indeed ‘weak links' in its defense which the proletariat could exploit. According to the logic of the ICC resolution, the workers in Russia should have dreamed about bourgeois democracy, since they had not directly confronted the more sophisticated mystifications of the bourgeoisie in the West. But despite the pleadings of the Mensheviks, they didn't waste their time with that. The degree of self-organization achieved; the extension of the struggle throughout Russia; the workers' unrest in neighboring countries; and the weakness of the bourgeoisie they had to confront: these made possible a goal far beyond that, it made possible the goal of a revolutionary victory in Russia with a reasonable hope that other countries would rapidly follow.

Today, however, any fraction of the proletariat in struggle is facing a united world bourgeoisie. There are no more weak links in capitalism's defense. What was possible then isn't any longer and since class consciousness is bound to what is objectively possible, revolutionary consciousness will require more time to mature, to allow class forces to grow much larger than was required in 1917. If class forces are not developed on an international scale beyond a limited area like western Europe, and if capitalist mystifications succeed in keeping the struggles isolated from each other and prevent the proletariat from becoming conscious of its common interests and perspectives, then no mass strike, regardless of where it happened, could lead to "the full development of the political consciousness indispensable for revolution", because it would be impossible for the workers to see the forces required for the task of defeating a united world bourgeoisie. Under such circumstances a mass strike would be bound to stagnate, which means to go rapidly downhill. Because the possibility of a further proletarian goal could not be perceived and thus be absorbed by the proletariat's consciousness, the degree of self-organization could not be maintained and would have to wither away, and a false perspective based on bourgeois mystifications would inevitably take hold. The ICC didn't realize this when it wrote, more than three months after the dismantling of the autonomous class organization in Poland, "The movement, far from dying down, has become stronger" (IR 24, p 4) and when later, in the framework of its ‘weak link critique', it attributed the success of capitalist mystifications in Poland to the "specificities" of the eastern bloc and Poland in particular.

The weight of specificities

As the ICC wrote, "the idea that there are national or bloc ‘specificities' ... will be pulverized more and more by the leveling down of the economic conditions in all countries and of the living conditions of all workers." (IR 29, p 4) That does not mean that revolutionaries have to deny that there are all kinds of differences between workers of different countries, sectors and regions, which capital uses to divide them. But the power to divide does not stem from the ‘specificities' themselves but from capitalism's global ability to maintain illusions in its system. Without the progressive demystification of these illusions by the crisis and the class struggle, workers will remain isolated in their ‘specific' situations in the strong countries as well as the weaker ones. The powerful position of the church in Poland might be specific for that country, but there is nothing specific about the mystifications this institution uses against the workers' struggle - nationalism, pacifism, legalism, etc. In other words, those mystifications are not powerful because the church is powerful but it is the other way around: the church fulfils that left in opposition role because the lack of depth of the crisis (not in Poland but on an international scale) and the immaturity of the development of the workers' struggle (again on the international level) permits capital to use these mystifications with success. This means that revolutionaries have to stress again and again the worldwide unity of the proletariat's struggle and unmask the mystifications behind the specificities. That means struggling against the fear that extension of the struggle and generalization are not possible because of the specific differences, and its corollary - the illusion that a victory, a full development of revolutionary consciousness is possible within one country or one part of a continent alone.

Now let's take a closer look at the main specificities which the ICC sees as responsible for the western European workers' lack of company on the road to revolutionary consciousness.

The ‘scarcity' in the eastern bloc

"The specific form that the world crisis takes there (scarcity), obstructing the development of a direct and global consciousness of the causes of the crisis (overproduction) ..." (‘Resolution of the critique of the theory of the weak link')