February 2018

- 654 reads

On Marx and Epicurus

- 4070 reads

Under the heading ‘Readers’ Contributions’ we aim to encourage our readers and sympathisers to write texts and articles which can go into greater depth than is possible in our discussion forum, and so stimulate a longer term reflection. These articles, while being broadly based on proletarian politics, need not fully represent the positions of the ICC, or may deal with issues on which the ICC does not have a collective view.

Some notes on elements of Marx's 1841 doctoral thesis on The Difference Between the Democritean and Epicurean Philosophy of Nature and the profundity of the Epicurean "swerve"

Given the fragments, literally, of the works of Epicurus available to Marx at the time, the materialist analysis that he manages to develop from them is pretty amazing. After Marx's demise much more evidence of Epicurus' philosophy has been found: on charcoal remains of papyri in Philodemus' library in Herculeum, on the wall of Diogenes of Oenoanda and writings kept in the Vatican for whom Epicurus was strictly taboo. The mere mention of Epicurus (or Lucretius) led to torture or imprisonment by the Inquisition in Naples and all of their followers were consigned to the Sixth Circle of Hell. Marx was also assisted in this work on Epicurus by the poem On the Nature of Things and works of the aforementioned Roman poet Lucretius.

Titus Lucretius Carus was a great influence on the sixteenth century Italian materialist Giambattista Vico, and an even bigger influence on the workers' movement. He developed the idea of descent with modification, and understood that energy could neither be created nor destroyed. His poem was the basis for Lewis Henry Morgan's great work, Ancient Society... and thus Engel's work The Origin of the Family Private Property and the State. He laid out the tenets and philosophy of Epicurus in his poem. The renowned Epicurean scholar, Cyril Bailey who translated his work into English, said in 1928: "Looking back on his (Marx's) work now it is almost astonishing to see how far he got considering the materials then available and he was probably the first person to see the true distinction between the Democritean and Epicurean systems". And to a large part he did this by focusing on the meaning of the Epicurean swerve.

Epicurus' study of the atom allowed him to delve into "the nature of human sensation and existence". Benjamin Farrington, noted scholar of Greek philosophy, wrote: "Oddly enough it was Karl Marx in his doctoral thesis... who first took the measure of the problem and provided the solution... making Epicurus the deeper of the two (in comparison to Democritus) inasmuch as he laboured to find room in his system both for animate and inanimate being, both for nature and society, both for the phenomena of the external world and the demands of moral consciousness" (From Marx's Ecology, materialism and nature by John Bellamy Foster).

Epicurus' work removes the gods (almost entirely) and the fear and terror that they inspire in mortal man, opening the way for chance, possibilities and freedom: "That which is abstractly possible, which can be conceived constitutes no obstacle to the thinking subject, no limit, no stumbling-block". Continuing from this, only Marx could say from the fragments that he knew of: (that) "Epicurus therefore proceeds with boundless nonchalance in the explanation of separate physical phenomena" and this from the possibilities that brought them about. In contrast to Democritus, who also contributed to a materialist analysis, Epicurus posed the question of a tiny "swerve" in the atom against the straight, deterministic lines of the former. Cicero ridiculed this idea calling it "disgraceful" and said it was "entirely impossible" that the universe came about by "complexities, combinations and adhesions of the atoms one with another". Hegel suggested that he had nothing useful to say; similar criticisms were levelled against Epicurus by the 17th century French philosopher Pierre Bayle, but the strange reality of the quantum nature of the atom is now beyond doubt. Lucretius understood this: "... if the atoms never swerve so as to originate some new movement that will snap the bonds of fate" nothing would change, but this process does take place "in time unfixt, imperceptible to the senses and in the smallest possible space". The further relevance to quantum mechanics is evident. For Marx the swerve represents "the soul of the atom, the concept of abstract individuality".

Epicurus suggests qualities to the atom, size, shape and weight whose declination (swerve) opposes any determinism: (the atoms) "are therefore opposed to one another as immediate realities". Marx agrees with Lucretius, saying that "the declination breaks the fati doedra (bonds of fate)", and applied to consciousness "the declination is that something in its breast that can fight back and resist". The declination lifts the atom out of the domain of determinism. If atoms didn't swerve they could neither repel nor attract, and it's from this repulsion and attraction that, according to Epicurus with Marx: "the world of appearance emerges", appearance that is transformed by consciousness from essence. Repulsion and attraction go beyond Democritus' determinism, just as the swerve of the atom goes beyond the relative existence of atoms falling in fixed lines. Democritus assumes an infinite number of shapes of the atom up to infinite size. But according to Lucretius, "it is rather by a definite and finite number of shapes that the atoms are differentiated from one another", which is also another way of expressing the modern theory of the conservation of energy.

As for weight, in the view of Epicurus it exists only as a different weight and the atoms themselves are substantial "centres of gravity" with weight existing in respect of repulsion and attraction. In this way Epicurus anticipates the fact that all bodies, whatever their weight and mass, have the same velocity when they fall through space. Time is discussed by these Greeks in some ways similar to that of modern-day physicist Carlo Rovelli, and both Democritus and Epicurus agree that time is excluded from the atom. For the latter, infinite time exists within infinite space comprising infinite worlds, giving rise to free-will against superstition and fear of the gods. Following Epicurus, Lucretius writes: "... time by itself does not exist... It must not be claimed that anyone can sense time by itself apart from the movement of things or their restful immobility... accidents of matter, or of the place in which things happen". Marx calls this "the 'accidens' of accidens". Time is in opposition to space, time is change as change, and further for Marx, it is the "fire of essence" which can only be seen through reason: "... this reflection of appearance in itself which constitutes the concept of time, has its separate existence in the conscious sensuous. Human sensuousness is therefore embodied time, the existing reflection of the sensuous world itself".

There's a chapter called "The Meteors", by which Epicurus means all celestial bodies; and this is doubly important for the Greeks because their "philosophers worshipped their own minds in the celestial bodies" (like a "cult" according to Marx) and this was another factor in the elevation of the gods that Epicurus flatly rejected. Once the myth is removed from the heavens everything is possible, every explanation is sufficient. For example, there's not one explanation to a lightning strike but a number of interacting properties and reactions, and the task for Epicurus is to "trace their cause and banish the source of disturbance and dread". He takes comfort in the fact that everything is impermanent and unstable, not eternal and immortal. Marx says that Epicurus "in wrath and passionate violence" rejects those that propose one method of explanation of the Unique, Eternal and Divine in the heavenly bodies. The irregularity of orbits, the number of multiple possibilities involved in heavenly phenomena, the multitude of explanations is for Epicurus the road to calm, understanding and freedom. For Marx the contingency and freedom espoused by Epicurus, which before him was mechanical determinism, brought out the "active side".

Marx's materialism has strong roots in the swerve of Epicurus, showing that it could be an element in human emancipation from the material conditions of a world characterised by the development of human relations to its basic needs, from which consciousness develops. Chance and contingency play a part in this along with human ethical considerations. Marx wasn't uncritical of Epicurus since he was only interpreting the world, but his interpretation gave the world a direction and in the thesis Marx builds on some of his contradictions. He criticised his ideas of too many possibilities and his individualism but, again, these were part and parcel of the outcome. Engels, up to his death, was, enthusiastically with Marx all the way on the materialism of Epicurus. Engel's himself rejected much of bourgeois materialism in favour of the Greek "enlightenment", particularly Epicurus and Lucretius. He continued Marx's work on Epicurus and praised what he called the latter's "immanent dialectics". Epicurus recognised the estrangement of human beings from the human world in the shape of religion, now reinforced by the alienation of the labour-capital relationship, and had profound concerns about the well-being of the earth and the relationship of nature to man, points which Engels picked up and expanded on along with Marx.

A final quote from Marx in the thesis on Epicurus: "When human life lay grovelling in all men's sight, crushed to the earth under the deadweight of religion whose grim features loured menacingly upon mortals from the four quarters of the sky, a man of Greece was first to raise mortal eyes in defiance, first to stand erect and brave the challenge. Fables of the gods did not crush him, nor the lightning flash and growling menace of the sky.... Therefore religion in its turn lies crushed beneath his feet, and we by his triumph are lifted level with the skies.

The difference between Democritean and Epicurean philosophy of nature which we established at the end of the general section has been elaborated and confirmed in all domains of nature. In Epicurus therefore, atomistics with all its contradictions has been carried through and completed as the natural science of self-consciousness. This self-consciousness under the form of abstract individuality is an absolute principle.

Epicurus has thus carried atomistics to its final conclusion, which is its dissolution and conscious opposition to the universal. For

Democritus, on the other hand, the atom is only the general objective expression of the empirical investigation of nature as a whole.

Hence the atom remains for him a pure and abstract category, a hypothesis, the result of experience, not its active [energisches] principle. This hypothesis remains therefore without realisation, just as it plays no further part in determining the real investigation."

We are conscious now that far from being crushed, religion, particularly its fundamentalist versions in both east and west, has been fed and invigorated by decomposing capitalism. The task is to overcome this along with all the divisions that emanate from the breakdown of ruling class ideology and to this effect we have to salute the groundbreaking work of Marx on Epicurus.

Marx's appendix on Plutarch

At the end of Marx's dissertation is an appendix called: Critique of Plutarch's Polemic against the Theology of Epicurus, of which, like much of the latter's work, only fragments survive. Nevertheless, even here, Marx makes some significant points and looks at some new areas in these fragments that we can return to in the context of the whole. It's also worth remembering that this work of Marx developing on Epicurus showed his gradual independence from Hegel and demonstrated to him in the process the importance of religion and the unfolding necessity to try to develop a profound understanding of what religion meant for humanity and its emancipation, while contending that "No good for man lies outside himself".

For Plutarch, God was on the side of good against the wicked - the powerful nature of this aspect of religious ideology shouldn't be underestimated even to this day. Against Epicurus, Plutarch argued that if there was no God there was no joy or happiness. According to him, belief in God, as well as bringing relief from pain, fear and worry "indulges in a playful and merry inebriation, even in amatory matters!” Marx responds on the proof of God that gods are like imagined money - in the end there will be a price to pay. And anyway, proof of 'your' God is a disavowal of others and vice-versa. Plutarch divides society into the good, decent, intelligent and the bad and uncivilised whereas, according to Marx, Epicurus deals with the "essential relationship of the human soul in general". For Marx, Plutarch's objection to Epicurus' ungodly atomism poses the question of the eternal, unchangeable characteristics of man against those of change, free-will and self-consciousness. Plutarch's view of religion is based on the reform of the wicked by, first of all an animal-like fear and secondly, sentimentality: "There is no qualitative difference between this and the previous category. What in the first place appeared in the shape of an animal fear appears here in the shape of human fear, the form of sentiment. The content is the same" (Marx). After talking about sentiment Marx goes on to briefly talk about the "... naked, empirical ego, the love of self, the oldest love...".

Marx certainly has plenty of criticisms of Epicurus on the questions of mechanistics and "accidents" but wholly supports his view that events of human history are neither mere accidents nor merely arise out of necessity. Epicurus recognises and never denies necessity or subsistence but always insists that the bounds of both must be broken and this by the means of human reason and human consciousness.

In the dissertation Marx argues that Epicurus goes beyond the sceptical world of the Democratean atom and its "subjective semblance" by positing its "objective appearance". "Implicit in Epicurus' philosophy was the notion that knowledge both of the world of the atom (imperceptible to the senses) and of sensuous reality arose from the inner necessity of human reason embodied in abstract individuality and freedom (self-determination)." Marx's Ecology materialism and nature, John Bellamy Foster.

In his appendix on Plutarch Marx also takes aim at the German idealist philosopher Friedrich Schelling, whose positions degenerated into a defence of religion and from this a cock-eyed vision of nature. Schelling's appointment as Rector at the University of Berlin indicated the closing off of universities to the Young Hegelians and a definite turn by Marx into further profound applications of his work.

Marx took what was best about the enlightenment of Ancient Greece and defended and refined the analyses of Epicurus against the determinism of Democritus; and then he defended the materialism of the modern Enlightenment against the reactionary views of Schelling. Marx went beyond Epicurus while underlining his importance for a materialist analysis. He reined in some of his "exaggerations" and sharpened up his innate dialectics.

Baboon. 15.2.18

Rubric:

On recent attacks on the ICC on libcom

- 2804 reads

The publication of our article ‘Reflections on the split in the Anarchist Federation’[1] has been widely read (close to 1000 reads at the time of writing), but has also ignited a storm of virulent attacks on the ICC, led by two longstanding members of the libcom collective, Steven and Mike Harman[2].

The ostensible reason for these attacks was a short paragraph in the article describing the events at the Anarchist Bookfair which had precipitated the split in the AF, a clash between a group of radical feminists (labelled “Trans Exclusionary Radical Feminists” by their opponents) and supporters of “transgender rights” over the question of transphobia – hatred or discrimination against transgender people. This had not been the main focus of the article – the paragraph had figured as an introduction to a more general critical analysis of the statement of the group which had left the AF. But it was the central focus of the attacks on our article. We - or “the authors of the article” – were accused either of gross ignorance of the issues (and were given sundry links to sites where the basic terminology would be made clear to us) or of outright transphobia. The main evidence provided was that at the beginning of the article we had placed the word transphobia in inverted commas, as though it was not a real thing; but more importantly, that we had referred to transgender women (ie those who have “transitioned” from a male gender identity to a female one) as transgender males. According to our critics, we were thus providing support for the radical feminists, who had distributed leaflets at the Bookfair criticising proposed government legislation which will make gender identity a matter of subjective choice, because in the view of these particular feminists it will expose women-only spaces to the presence of people who they don’t consider to be women at all.

It’s true that this misuse of the current terminology was an error on our part, and we have made certain changes in the paragraph to make it clear that we are simply describing the position of the “TERFs” and in no way supporting them. But it was clear from the approach of posts attacking us that however much we altered the formulation used, we would still be judged guilty of promoting transphobia, because we have an entirely different approach to the whole issue. This is how Mike Harman deals with it. He cites the attempt by our poster on the thread, Alf, to focus on the real questions raised by the article: “is it true that significant parts of the anarchist movement are being pulled into the politics of 'identity', whether based on gender, sexuality, race or nationality?” and replies:

“You're asking the wrong question, because you don't understand the basis of the conflict. Another question to ask would be, ‘Why did two Green party members feel sufficiently emboldened that they could distribute transphobic leaflets at the anarchist bookfair, and put up posters in the toilets?’”

Harman’s post thus provides a justification for refusing to engage with the growing impact of identity politics on the anarchist milieu. Not only that, but Steven in particular repeatedly demanded that our entire article should be taken down – a clear attempt to silence us[3].

But in insisting that the one and only issue is the action of the “TERFs”, Harman also implies that unless you side with the anti-TERF resistance, you are providing ammunition for their transphobic agenda. In other words, what the posts by the libcom collective members really show is not our insidious prejudice against trans people, but the libcom collective’s own deepening involvement in identity politics or “id pol”. Small wonder that Steven (who is a remaining member of the AF) dismisses our view of the split as being an attempt – albeit partial and inadequate – to reject the growing weight of id pol, as “bollocks”.

For our part, we want to emphasise that not only do we not take sides in this clash between different brands of identity politics: we are opposed to all of them. As our sympathiser Baboon put it in a post on our forum: “I don't think that the fight between radical feminists and trans activists has any possible advantage for the proletariat or in any way assists the pressing needs of the class … I'd seen these two groups confronting each other on the TV weeks before the bookfair on Channel 4 news where (at a Gay Pride march I think) their confrontation was turning very ugly and very nasty[4]. At the bookfair apparently the police were called by one faction and both factions were involved in mobbing and scapegoating, a situation that showed nothing positive from a working class perspective and was entirely in line with certain populist developments arising from capitalism's decomposition”[5]

At the same time, both groups are founded on deep illusions in capitalist legislation. Some feminists seem to think that women are defended by current legislation, but will be undermined by the change. Meanwhile, some trans activists seem to think that the change to the Gender Recognition Act will be a great step forward for trans people. Both milieus have profound reformist illusions. And their goals are mutually exclusive, therefore deeply divisive.

WR, February 2018

[3] Echoed, more crudely, by the poster El Psy Congroo who simply told our comrade to “shut the fuck up”

[4] The incident in question actually took place at Speakers’ Corner in September 2017: https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2017/oct/26/woman-punched-in-brawl-b... [4]

Rubric:

Reflections on the split in the Anarchist Federation

- 3527 reads

The Anarchist Federation, one of the main anarchist organisations in Britain, has just been through a major split. Members in Leicester and London, including a number of founder members, have left the organisation following the tumult over the issue of “transphobia”[1] at October’s Anarchist Bookfair.

If we were right in our assessment of the AF as an internationalist anarchist group[2], this is a significant event which attests to growing difficulties across the entire spectrum of groups who are seeking to develop an authentic revolutionary opposition to capitalism – not only among anarchists but also within the communist left. We think that it is essential to understand the roots of these difficulties if we are to face up to the challenge they pose, and it is in this spirit that we aim to critically analyse the statement issued by those who have decided to leave the AF.[3]

The attempt to break with “identity politics”

The statement of the seceders begins thus:

“It has been over a month since the London Anarchist Bookfair and as a movement we are still reeling, with deep divisions between people who had respect for each other and once worked well together. We are still shocked, horrified and saddened by events as are most people, no matter what perspective or interpretation they have on what happened and the role of the Bookfair collective.

We were, until recently, members of the AF who did not sign the initial statement that was issued by Edinburgh AF and signed by two other AF groups, nor did we support the statement issued by other campaigns and organisations. We did not want to respond immediately as there are so many issues involved and emotions are strong. We hoped that after some time we could give a political assessment of the situation rather than just a knee-jerk reaction based on our emotional response to events and statements from other groups”[4].

The former members have reconstituted themselves into London Anarchist Communists and Leicester Anarchist Communists[5].

It’s not possible here to deal in any detail with the events at the Bookfair, which caused such ructions across the anarchist milieu and even reached the national press[6]. In essence it involved a clash between a group of feminists who intervened at the Bookfair with a leaflet arguing that new government legislation on “transgender rights” is an infringement on women’s rights to organize separately, since it would allow people who they – the leafleters – don’t consider to be women at all into spaces reserved by or for women. The leaflet provoked a lot of anger from “trans rights” supporters, who saw it as an attempt to whip up fear of transgender people by a tendency they call “Trans Exclusionary Radical Feminists” or TERFS, and one of the women supporting the leafleters, a well-known activist who was involved in the MacLibel case and has been targeted in a particularly vicious way by the undercover police, was subject to mobbing and accused of being a fascist. The Bookfair Collective, which attempted to intervene in the situation to calm it down, subsequently issued a statement saying that this would be its last Bookfair – it has experienced similar clashes in a number of other Bookfairs and its patience has run out[7].

These events are not unconnected to other scandals centred on the question of morality and behavior which have rocked the anarchist movement in the last few years, the most notable of which are “Aufhebengate” and the “Schmidt affair”[8], both of which raise the problem of the role played in the anarchist milieu by individuals with a dubious relationship with the police (in the first case) and with out-and-out racists in the second. We have also seen a substantial part of this milieu plunging into support for “national liberation” in the shape of the “Rojava revolution”, armed enclaves in Syria controlled by the Kurdish nationalists of the PKK and based on a semi-anarchist ideology of “democratic confederalism”[9], and an extremely widespread support for anti-fascism which was highlighted by the incidents around Charlottesville in the USA[10].

These developments are not taking place in a vacuum. The tendency, within anarchism, to abandon class politics and look for solutions in various forms of identity politics – whether based on gender, race, or nation – while not new, are certainly being exacerbated by the characteristics of the current historic period, in which capitalism is sinking towards barbarism while the working class, weakened by all the divisions engendered by this decomposing society, has found it extremely difficult to resist as a class and above all to rediscover its own perspective for the future of humanity. In a situation where the working class is tending to lose its sense of itself as a distinct social force, it is not surprising that the problem of class identity is being obscured by a fixation on other, more specific identities – a fixation which, while linked to genuine oppressions, tend to obscure the central problem of exploitation and the capitalist social relation.

The statement issued by the seceding groups is highly critical of the mobbing witnessed at the Bookfair. And while it affirms the importance of fighting against all particular forms of oppression, including transphobia, it also contains a questioning of the identity-based politics which it feels has become increasingly dominant within the AF, and a strong desire to return to “class struggle anarchism”. The question of internationalism is also directly posed by this split, because, although the AF published a fairly clear statement on the “Rojava revolution” some time ago[11], some of the comrades who left the organisation also consider that pro-PKK positions have also been increasingly influential within the organization[12].

These aspects of the statement are expressions of a proletarian reaction to the engulfing of the AF in the mire of identity politics and a drift towards support for radical forms of nationalism. They confirm what we wrote in our two-part article on internationalist anarchism in the UK, where we argued that for all its concessions to leftist campaigns, the AF was in the tradition of internationalist anarchism – of those currents in the anarchist movement which have stood against any participation in imperialist war[13]. The revival of the term “anarchist communism” (the AF had originally been called the Anarchist Communist Federation) is symbolic of this will to recover the healthiest parts of its tradition, which they feel can no longer be done within the AF.

And yet: the very fact that these criticisms of identity politics are carried out in the historic framework of anarchism means that they don’t – and cannot – go far enough.

Anarchist obstacles to theoretical advance

What is the evidence for this claim?

· The statement begins by admitting how difficult it has proved to overcome all the divisions within the working class and to build a revolutionary movement committed to the overthrow of capitalism. But it gives little sign of trying to situate these difficulties in the overall context of the present period – a period, as we have noted, marked by a loss of class identity and a low level of class struggle. It’s true that prior to the split the Leicester group of the AF had held a meeting in Leicester and one at the Anarchist Bookfair, as well as writing an article that started a thread on libcom, under the heading ‘Is the working class movement dead?’[14], which posed serious questions about the problems facing the working class and revolutionaries. There is a recognition in the article that the class struggle has been weakening over a long period but the approach to the problem in the presentation to the meetings is essentially an empirical one which is unable to place it in the global, historic context of capitalism’s terminal phase of decline.

· Although it affirms the central role of the class struggle, the statement does not pose the fundamental theoretical issue: the nature of the working class as a historic, revolutionary class, or as Marx famously put it in 1843: “a class with radical chains, a class of civil society which is not a class of civil society, an estate which is the dissolution of all estates, a sphere which has a universal character by its universal suffering and claims no particular right because no particular wrong, but wrong generally, is perpetuated against it; which can invoke no historical, but only human, title; which does not stand in any one-sided antithesis to the consequences but in all-round antithesis to the premises of German statehood; a sphere, finally, which cannot emancipate itself without emancipating itself from all other spheres of society and thereby emancipating all other spheres of society, which, in a word, is the complete loss of man and hence can win itself only through the complete re-winning of man. This dissolution of society as a particular estate is the proletariat”. (Critique of Hegel’s Philosophy of Right)

It is this conception which enables us to understand why the struggle of the proletariat contains, in potential, the solution to all the particular oppressions spawned by capitalist society. But this conception of the proletariat is, of course, the one developed by Marx and the marxist movement, which affirms that the class struggle is not restricted to the economic sphere but has numerous dimensions: social, political, moral, intellectual. It was this understanding which enabled Lenin, that bugbear of the anarchists, to develop a critique of the Economist vision which limits the class movement to something that takes place in the factories and essentially on a day to day basis. And in many ways this is precisely the conception of the main currents in anarchism – most notable the anarcho-syndicalists, but also of those who produced the statement, for whom a class struggle orientation seems to boil down to “getting involved” in the workplace and the local community, which is presented almost as a panacea: “our answer to the first issue” – the reluctance of working people to get involved in revolutionary politics – “is that we need to make sure as anarchists we are directly involved in struggle, in the workplace and the community”. The issue for us here is not whether revolutionaries should engage with struggles in the workplace or the neighbourhood, but the content of that engagement – its methods and objectives, which are nowhere posed in the seceding statement. Otherwise comrades risk burning themselves out in non-stop activism whose real content is essentially a trade unionist one. This is evident in the case of the anarcho-syndicalists whose “organising” role is linked to a project of building a “revolutionary union”. But even those who appear to be more critical of trade unionism can be led back to union-building through a simple focus on day-to-day workplace organising. It was pointed out on the libcom thread about the AF split that some of those who left the AF had previously joined the IWW, which is not entirely consistent with the AF’s position on anarcho-syndicalism, while some of the campaigns of the more “autonomist” Angry Workers of the World group in West London seem to be heading towards calls to build new IWW or “independent union” branches[15].

· This restricted view of the class struggle does not offer any real alternative to the ideas of “idpol”, for whom being working class is another particular oppression, another separate identity with its own rights to defend. The statement’s critique of identity politics and the kind of mobbing witnessed at the Bookfair makes some valid points – in particular by recognising that fighting against oppressive and divisive ideologies is one that takes place inside the working class, and that those proletarians who are weighed down by various kinds of prejudices need to be won over in the course of the class struggle, not treated as enemies. And yet the ABC of identity politics is not questioned: “We support oppressed groups to organise autonomously”, without any discussion about whether such forms of organising – by gender, sexual orientation, race – tend to become inter-classist by definition and create obstacles to a wider class unity. The statement mentions that it disagrees with the statements put out by Edinburgh and two other AF groups, but it doesn’t mention the fact that one of these groups was the “Trans Action Faction” within the AF[16], and no criticism is made of the organisational model adopted by the AF, which presents itself as a myriad not only of local groups but of groups organised around sexual and other identities. Again on the organisational question, while it’s recognised in the statement that a lot of people entered the AF without really agreeing with its Aims and Principles, the new group goes no further than reprinting the original document and doesn’t appear to have an answer to the pertinent question posed by Darren P on the libcom thread: “Just out of interest how was it that people whose politics are closer to liberal idpol than anarchist-communism came to be the majority in the AF anyhow? Isn’t there any kind of screening process for new members? In other words, is there not a need to examine the ‘entry requirements’ of a genuine revolutionary organisation?”[17]

Does any of this mean that all the problems posed by the different forms of oppression and division reinforced by capitalist society have been solved by the marxist movement? Not at all: even when we are talking about authentic marxism and not its Stalinist or leftist caricature, its various currents have not been immune from workerist ideologies, reductionist visions of class, and even overtly “patriarchal attitudes”. But we are convinced that it’s only the marxist, historical method that will enable us to understand the origins of different forms of oppression and the way to oppose and overcome them, which can only mean starting from a lucid class standpoint that states openly that identity politics are a dead-end[18].

For us, the underlying problem is that, historically speaking, anarchism itself stems from deep confusions about class: the Proudhonist tendency classically expressed a reaction by the artisan to being dissolved into the proletariat; the Bakuninist current tried to respond to the development of the proletariat with a more collectivist approach but without jettisoning the attachment to the centrality of “liberty” versus “authority; the anarcho-syndicalists, while being a healthy response to the parliamentary cretinism overcoming social democracy at the beginning of the 20th century, fell into the workerist view of the class struggle we mentioned above, evading or even rejecting the political dimension of the class movement. This means that simply returning to these historic roots will not provide the basis for a real clarification and a genuine advance.

There is also an inherent tendency within anarchism towards what many anarchists themselves describe as “the Big Tent” – a kind of family conception in which almost everyone who pins the “anarcho-“ or “libertarian” label on their jacket is welcome through the door. This is typified by the Anarchist Bookfair which has always had the vaguest and most inconsistent criteria for participation, but in a narrower sense the same criticism can be made of the AF, which reveals itself to be a marsh inhabited by different and often antagonistic species.

Anarchists have often taken offense at our use of terms the marsh or the swamp to describe the milieu they inhabit, but we see it as a necessary characterisation of a real political terrain in this society – the middle-ground between the two major classes, the proletariat and the bourgeoisie, made up not only of direct expressions of the intermediate layers (urban petty bourgeoisie, peasantry etc) but also, on the one hand, of degenerating proletarian currents heading towards the ground of bourgeois, leftist politics, and on the other hand, of groups and individuals that are seeking seriously to reach the proletarian shore. A place of transition, but not a place to get bogged down.

In our series on the communist left and internationalist anarchism, we insisted on the need for fraternal discussion between our tendency and those anarchists who indeed express a proletarian vision even if, to our mind, they have not yet left the old swamp behind entirely. Regarding the split in the AF, for all our criticisms, we remain open to further debate, not only with those who left but also with those who chose to stay in the AF. For us, political criticism is not in contradiction with fraternal discussion, and should not be confused with sectarianism[19].

Amos 23.2.18

1. This is the current “normal” term for discrimination, hatred or prejudice against people who opt for a different gender identity than the one given when they are born. However, even among those activists involved in the issue, it is not immune from criticism: "we’ve been intentionally moving away from using words like ‘transphobic’, ‘homophobic,’ and ‘biphobic’ because (1) they inaccurately describe systems of oppression as irrational fears, and (2) for some people, phobias are a very distressing part of their lived experience and co-opting this language is disrespectful to their experiences and perpetuates ableism." https://lgbtqia.ucdavis.edu/educated/glossary.html [6]

2. https://en.internationalism.org/series/1292 [7]

https://en.internationalism.org/wr/344/brit-anarchy [8]

https://en.internationalism.org/wr/345/brit-anarchy [9]

3. Certain changes have been in this article since it was first published on 5.2.18. The reasons for these changes are explained in our accompanying article 'On recent attacks on the ICC on Libcom' https://en.internationalism.org/icconline/201802/14928/recent-attacks-icc-libcom [10]

4. https://communistanarchism.blogspot.co.uk/2018/01/class-struggle-anarchist-statement-on_1.html [11]

5. [email protected] [12]; https://leicesteraf.blogspot.co.uk/ [13]

6. https://www.theguardian.com/society/2017/nov/26/transgender-anarchist-book-fair-transphobia-row [14]

7. Statements by the Bookfair Collective can be found at anarchistbookfair.org.uk [15].

8. See our statement on “Aufhenebgate”: https://en.internationalism.org/icconline/201305/7746/aufhebengate [16] on the “Schmidt affair”: https://libcom.org/discussion/ak-press-allegations-against-michael-schmidt [17]

9. https://en.internationalism.org/icconline/201412/11625/anarchism-and-imperialist-war-nationalism-or-internationalism [18]

10. en.internationalism.org/icconline/201709/14390/anti-fascism-still-formula-confusion [19].

We should also mention that there has also been a split in the main international organization of the anarcho-syndicalists, the International Workers’ Association, which appears to centre round its most numerous section, the CNT in Spain. See for example https://libcom.org/article/cnt-and-iwa-part-2-crisis-iwa-seen-cnt [20].

11. https://libcom.org/article/anarchist-federation-statement-rojava-december-2014 [21]

12. See https://libcom.org/forums/anarchist-federation/whats-going-afed-27122017 [22], especially p 2 and 3

13. See note 2 for references

14. https://libcom.org/article/working-class-movement-dead [23]

15. Post 184, Steven [24]. On the AWW’s drift towards syndicalism: “Workplace groups: Currently we work in a major warehouse of a supermarket chain and factories of a major ready-meal producer and try to establish workers groups. Together with the IWW we try to organise independent union structures in ten local companies”. https://libcom.org/article/migration-and-national-social-democracy-britain [25]

16. afed.org.uk/afed-trans-action-faction-statement-in-response-to-events-at-london-anarchist-bookfair-2017 [26]

17. Post 19, Darren P [27].

18. This is why we are also publishing the article ’The dead-end of racial identity politics’ by the US group Workers’ Offensive in this issue (www.workersoffensive.org/single-post/2017/10/13/The-Dead-End-of-Racial-I... [28])

19. In this regard we note that the new group carries on a practice established for some years now by the Anarchist Bookfair (not to mention numerous other radical websites), in that it publishes a link to the Communist Workers’ Organisation, a left communist organisation whose positions are close to ours, but not to the ICC – just the Bookfair allowed the CWO to hold a stall and meetings while requests from the ICC to do the same were rejected year after year. This attitude is incoherent and a real expression of sectarianism. If anyone in the anarchist world considers that the ICC deserves to be treated like a pariah, let them argue the case, and we will respond with our own arguments.

Rubric:

Suffragism or communism?

- 1620 reads

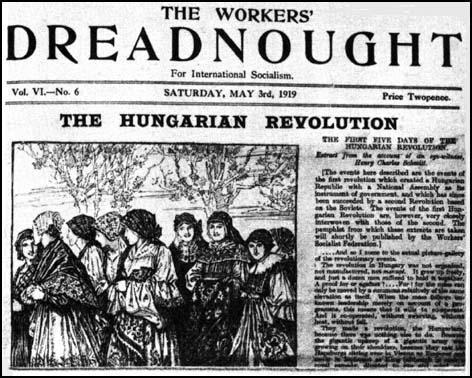

Faced with the torrent of “celebration” about how women (or some women) were given the vote in 1918, we are pleased to publish this short response by a comrade who has moved close to the views of left communism – and thus to the ideas of Sylvia Pankurst in 1918, who exposed the granting of the vote as a deception aimed at stemming the tide of revolution that had been provoked by the horrors of the First World War[1]. ICC

The Workers’ Socialist Federation began life as the East London Federation of the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU), the primary organisation for women’s suffrage led by Emmeline and Christabel Pankhurst. In contrast to the WSPU, the East London Federation was disproportionately composed of working-class (as opposed to middle-class) women, and open to men. Sylvia Pankhurst was therefore concerned with social reforms and industrial action for the improvement of the dire conditions of the working-class, whilst the WSPU privileged [propertied] women’s suffrage above any other cause and aimed to appeal to middle-class women. The working-class and reformist nature of the East London Federation led to its expulsion from the WSPU in 1914.

During the First World War, most of the international, women's suffrage movement – e.g. the WSPU in Britain, or National American Woman Suffrage Association in the US – rallied to the support of their countries’ war efforts, engaging in patriotic/nationalist, pro-war sloganeering. The war exacerbated the poverty and hardships of the working-class in East London, and Sylvia Pankhurst tried in vain to alleviate the suffering of workers through charity, lobbying for reforms and co-operatives.

The Russian revolution led to a radical alteration in Sylvia Pankhurst’s politics. When Pankhurst changed the name of her organisation from the “East London Federation of Suffragettes”, to the “Women’s Suffrage Federation”, to “Workers' Suffrage Federation”, and finally the "Workers' Socialist Federation", and the name of her paper from Women’s Dreadnought to Workers' Dreadnought, it illustrated this shift in her politics, away from ‘women’ (an interclassist category), towards working-class women, finally to the working class in general, and her ultimate rejection of the politics of reformist suffragism in favour of communism.

By 1918/9, Pankhurst recognised that it was pointless, and in fact reactionary, to campaign for suffrage amidst a world, proletarian revolutionary wave. At a time when the very existence of parliaments and nation-states was put into question by the revolutionary working-class, whether or not the working-class, or women, or middle-class women, should have the right to vote in elections to capitalist parliaments had simply lost all relevance. Parliaments were no longer a site of meaningful, political contestation for the proletariat, the future was to be found in the form of territorial soviets (workers' councils).

“The Communist Party, believing that instruments of capitalist organization and domination cannot be used for revolutionary ends, refrains from participation in Parliament and in the Bourgeois Local Government system. It will ceaselessly impress upon the workers that their salvation lies not in the organ of the bourgeois “democracy,” but through the Workers’ Soviets.

The Communist Party refuses all compromise with Right and Centrist Socialism. The British Labour Party is dominated by Opportunist Reformists, Social Patriots, and Trade Union Bureaucrats, who have already allied themselves with capitalism against the workers’ revolution at home and abroad. The construction and constitution of the British Labour Party is such that the working masses cannot express themselves through it. It is affiliated and will remain affiliated to the Second International, so long as that so-called International shall exist.” (The Communist Party: Provisional Resolutions towards a Programme, 1920)

This great public campaign around celebrating suffragism, and the attempt to portray Sylvia Pankhurst as a suffragette, rather than the anti-parliamentary communist she became, is part of a ruling-class ideological offensive: to recuperate what can be recuperated, to cover-up what can't be recuperated, to rewrite history, leaving-out all the revolutionary bits. In general, undermining the historical memory of the workers' movement in the centenary years of the worldwide, revolutionary wave of 1917-23.

Why is the ruling-class so loud in its celebration of the Representation of the People Act 1918, as some great moment in British history? Why does the ruling class portray suffragettes as national heroes? What would the left communist Sylvia Pankhurst have thought about this national celebration of suffragism?

“It is interesting to observe that the legal barriers to women’s participation in Parliament and its elections were not removed until the movement to abolish Parliament altogether had received the strong encouragement of witnessing the overthrow of Parliamentary Government in Russia and the setting up of Soviets.

Those events in Russia evoked a response throughout the world not only amongst the minority who welcomed the idea of Soviet Communism, but also amongst the upholders of reaction. The latter were by no means oblivious to the growth of Sovietism when they decided to popularise the old Parliamentary machine by giving to some women both votes and the right to be elected.” (Workers’ Dreadnought, 15th December 1923)

Is it not the case that all those celebrating suffrage are falling for democratism?

“Even were it possible to democratise the machinery of Parliament, its inherently anti-Communist character would still remain. The King might be replaced by a President, or all trace of the office abolished. The House of Lords might disappear, or be transformed into a Senate. The Prime Minister might be chosen by a majority vote of Parliament, or elected by referendum of the people. The Cabinet might be chosen by referendum, or become an Executive Committee elected by Parliament. The doings of Parliament might be checked by referendum.

Nevertheless, Parliament would still be a non-Communist institution. Under Communism we shall have no such machinery of legislation and coercion. The business of the Soviets will be to organise the production and supply of the common services; they can have no other lasting function. ” (Pankhurst, 1922)

Craftwork, 12.2.18

[1] This article was first published on libcom.org, https://libcom.org/forums/history/suffragism-or-communism-11022018#new [30]. See also the article https://en.internationalism.org/icconline/201512/13704/sylvia-pankhurst-... [31]

Rubric:

The weaknesses of the PCI on the question of populism (part I)

- 1166 reads

In number 523 of its paper, Le Proletaire, dated February/March/ April 2017, the International Communist Party (PCI) published an article: Populism, populism you say?, in which it confronts this phenomenon and its current growth and, on the basis of this analysis, also undertakes a criticism of the analysis of the ICC on this question. The first part of our response to this polemic will be centred on the elements of analyses used by the PCI itself in order to evaluate its capacity to explain the phenomenon of populism.

We must say first of all though, through its positions, the PCI places itself in the defence of a proletarian point of view. Through this it demonstrates that it is still situated in the camp of the proletariat and that it globally defends the positions of the communist left.

What is populism, according to the PCI?

The comrades of the PCI correctly note:

- that other parts of the bourgeoisie use populism ideologically so as to drive proletarians onto the electoral terrain around the mystification of the "defence of democracy". We are thus in agreement with the PCI on the fact that the false opposition between populism and anti-populism is an ideological trap which serves the interests of the bourgeoisie.

- that the greatest danger for the working class is not the extreme-right but the left of the political apparatus of the bourgeoisie: "(Populism) cannot however replace the infinitely more powerful counter-revolutionary role that classic reformism plays (qualified by the PCI as the parties of the left), solidly implanted as it is in the working class and thus able to paralyse it" and these comrades are equally clear on anti-fascism, which completely distinguishes them from the positions of the extreme left of capital. They were unambiguous in denouncing the call to vote for Chirac in 2002 and at the last elections they once again denounced the electoral and democratic mystifications[i] .

Also Le Proletaire rightly emphasises that demagogy is not at all peculiar to populism, and the same goes for electoral promises. We undoubtedly share the same proletarian ground.

But what is the analysis of populism advanced by the PCI? Above all, it assures us that it is of a petty-bourgeois nature. In order to support this it provides a quote from Marx taken from the 18th Brumaire of Louis Napoleon Bonaparte: "Only one must not get the narrow-minded notion that the petty bourgeoisie, on principle, wishes to enforce an egoistic class interest. Rather, it believes that the special conditions of its emancipation are the general conditions within whose frame alone modern society can be saved and the class struggle avoided".

This general characterisation of the petty-bourgeoisie remains perfectly valid but what relationship, what link does that have with the billionaire Trump; with the advocates of Brexit? We have no idea... it explains nothing about the present situation. The only historic element that it gives is the reference to populism of Russia in the XIXth century. Again, we don't see any relationship between Russian populism of the XIXth century (relationships between the intellectual petty-bourgeoisie and the peasantry, the methods of this petty-bourgeoisie of the time oriented towards individual action and terrorism) with the present day, except instead of referring to Trump, the Tea Party or the currents of the extreme right today (the Front Nationale and other extreme right wing populists in Europe) the PCI talks to us about populism "in general". In this way, through its indistinct rejection it mixes up in the same "petty-bourgeois" rubbish bin the populism of the extreme right (Trump, Le Pen and the partisans of Brexit) or again the zealous propagandists of bourgeois democratic mystifications (‘Democracy Now’ in Spain or the altermondialists) with authentic reactions of the working class, certainly still influenced by illusions in democracy, such the Occupy and Indignados movements...

What can one draw out of such a confusion that sees populism equivalent only to the petty-bourgeoisie, while schematically glossing over an analysis of reality and seeking to track down everything that it thinks points to the ideology of the petty-bourgeoisie? Nothing! Other than it shows a total absence of an analysis of the phenomenon of populism and its historic evolution in order to understand how it corresponds to the present situation.

By substituting an assortment of ready-made schemas for an analysis of populism, Le Proletaire ends up with aberrations and stupid affirmations completely disconnected from reality: such is the case when it raises the question of a "workers' aristocracy" in order to explain the influence of populist themes in the ranks of the workers. This "theorisation", made by Engels and followed by Lenin, was already an error in their times because it aimed to explain the propagation of bourgeoisie ideology (not specifically that of the petty-bourgeoisie) in the workers' ranks. Moreover, the most experienced workers who have the best living and working conditions with the highest wages are not those most open to the present populist ideology. The reality is contrary: it is those who are most hit with the full force of the crisis and unemployment in the most grim and ravaged regions (the ex-mining basin in the north of France or the old steel-working bastions of Lorraine, where the FN made an electoral breakthrough), who are the most permeable to the themes of populism. Reality contradicts the absurd thesis of the PCI on the weight of a "workers' aristocracy" in the question of populism today[ii].

A schematic vision of a bourgeoisie without contradictions

Le Proletaire thus sees populism as a sort of rational and mechanical defensive reaction of the layers of the petty-bourgeoisie, of its particular economic interests globally compatible with, or assimilated to, the interests of the national capital. This leads them to avoid the real problem. The text even labours to show that populism doesn't pose the least problem for the bourgeoisie by using photographic empirical findings as "evidence": thus it refers to the fact that just after Trump's election Wall Street registered a stock-exchange record (along the same lines it uses a similar sledge-hammer argument of the highs of the London stock exchange after the Brexit vote in order to affirm that "the leadership of the British bourgeoisie do not at all think that this rupture is a serious problem for them"). The PCI take up the outdated and erroneous vision of the XIXth century of a bourgeoisie which plays the stock-market, whereas the stock-market is the domain par excellence of a day-to-day, short-term vision, guided by the immediate profits of the capitalists. Moreover it's for that reason that the bourgeoisie never calls into question this type of institution but make it depend on the general interests of its state, its administration, its "schedules". In reality, if the election of Trump was immediately followed by a hike in the Wall Street stock market it was simply because it was already announced that taxes would be lowered on businesses and this could only lead to a favourable welcome by the shareholders.

Another reason developed by the article doesn't get much traction either: the idea that Trump definitely serves the common interests of the bourgeoisie, since there have never been so many billionaires in the same government. There's no doubt about the capitalist nature of the government and the fact that it's full of the richest elements. That doesn't mean that it’s guaranteed to serve the best general interests of the capitalist system. We can suppose that the PCI also think that Brexit will definitively serve the interests of British capital. But we don't really see how Brexit strengthens British capital and the PCI doesn't say anything to support this notion.

It's important to reveal what the PCI doesn't say and the questions that it doesn't pose. What is the strategy followed by the American bourgeoisie with the election of Trump? What is the interest of the British bourgeoisie in carrying out Brexit? Do these results strengthen them in the defence of their economic and imperialist interests in the arena of global competition? The PCI says nothing about that and provides not the least serious argumentation in this respect. The PCI is certainly correct to affirm that nationalism is, given the competition between states, a privileged means to try to draw the ranks of the bourgeoisie together behind the defence of the national capital, but that gives no explanation nor any other framework for understanding the phenomenon of populism and still less, its present development. That makes it unfit to report on the numerous problems of present society and analyse their evolution.

The article of the PCI is obliged to pay lip-service to the idea that populism bothers or concerns a part of the bourgeoisie but it doesn't explain why when it says: "Without doubt some of its striking declarations have raised the eyebrows of certain capitalist sectors: the threat of hitting imports with raised tariffs would be a severe blow for a number of industries which have delocalised a part of their production or for the large distributions centres. But one can bet that the capitalists at the head of powerful groups of interest would make that clear to their colleague Trump". Similarly the PCI is obliged to recognise that the programmes of the populists "at certain points come into contradiction with the interests of the biggest, most internationalist capitalist groups". But they see that as an epiphenomenon that has no consequences and they depart from the presumptuous explanation that the bourgeoisie will as always use these contradictions for its own profit and overcome them. It is clear that the election and the policies of Trump a year on go in a totally opposite direction to those foreseen by the PCI, according to which the bourgeoisie would listen to reason and put a stop to the pretentions of Trump. At the present time a great part of the American bourgeoisie is plunged into disarray and several sectors, including his own camp, are trying to find the means to remove him or look for some other means to dislocate the presidential functions. For a year we've seen a growing discredit, a denunciation of Trump’s lack of seriousness, of the incoherent and chaotic policies being undertaken by the leading world power at the international level. For example, Trump's recognition of Jerusalem as the capital of Israel constitutes, among other things, a flagrant illustration of an international policy which has only thrown oil on the fire and stirred up a new focus for uncontrolled violence in the Middle East. At the same time we see an accumulation of obstacles facing the policies favoured by the administration (including the repeal of "Obamacare", the great Trump warhorse), the incessant waltz of resignations of the highest officials, to name just some examples of this disorder at the highest levels. In Britain, for a year now Brexit has posed serious problems to the health of the national capital, particularly by weakening and considerably undermining its power through the flight of international capital that it has provoked; and this despite the financial sector always being a strong point of the British economy. Faced with a succession of setbacks and contradictory initiatives to reach an agreement with the EU, Theresa May is more and more weakened and openly accused by her peers of incompetence, lack of preparation and confusion[iii].

That doesn't at all mean that Trump becoming president, nor the victory of Brexit, are fatal blows to capitalism, no more than it will prevent the United States or Great Britain remaining dominant imperialist powers. Neither does it prevent the bourgeoisie from trying to channel the problems linked to populist decisions and even utilising and exploiting the manifestations of the weight of populism to accelerate the decline in class consciousness, especially themes like nationalism or the defence of democracy. But the PCI, by focusing on the undoubted ideological use of populism by the bourgeoisie, totally misses the problems posed by the general dynamic of capitalism today, by the accumulation and exacerbation its contradictions, including within the bourgeoisie itself. It completely misses the stalemate between the classes and the growing tendency towards barbarism, of which populism in its present form is one of its most significant manifestations. Similarly, it completely underestimates the threats, the dangers and the traps (nationalism, channelling of the false choice between populism and anti-populism) and the growing disorientation and disarray in the class identity of the proletariat.

The consequences, following the election of Trump and the referendum on Brexit, of putting populist programmes and policies into practice are totally denied and ignored, as if the bourgeoisie of these two powers, although among the most powerful and experienced in the world, were immunised from danger and the policies undertaken and the economic orientations taken since these events run no risk of disastrous consequences for the national and world capital. The recent example of the situation in Germany following the legislative elections and the first time entry to parliament of the far-right AfD (Alternative for Germany), with 87 seats and 13.5% of the vote, once again confirms the historic tendency for the development of populism. This phenomenon in Germany is particularly strong in the old industrial centres, in particular the ex-GDR (East Germany) which doesn't at all correspond to the reductionist and false vision of the PCI.

"Nothing new under the sun": a fixed vision of history

Instead of analysing and explaining the growth, development and the dynamic of the populist phenomenon, the PCI stubbornly say in respect of the present phenomenon of populism there is "nothing new under the sun". Thus they have no framework of analysis. For it, the question of the growth of populism is almost an invention by the media, a simple instrument of propaganda. As it says at the beginning of the article, populism is nothing other than "a political orientation which denies the division of society into classes" aiming solely "to make the proletariat lose its class orientations". Which is an extremely reductionist view and comes down to saying that the growth in power of populism only corresponds to a manoeuvre, set-up and orchestrated by all parts of the bourgeoisie against the working class.

Rather than explain a phenomenon that it doesn't understand, the PCI denies reality and really gives the impression that there are no genuine contradictions within the bourgeoisie, as if it was a simple sum, an aggregate of different interests: bosses, shareholders, states, parties and candidates... It has the vision of a conscious, all-powerful bourgeoisie that has no internal contradictions and which puts forward such and such a card according to its needs, aimed exclusively against the working class, thus allowing it to divert the latter's discontent. It's paradoxical because at the same time as the PCI advances this need of mystification, it recognises that the threat to the bourgeoisie from the working class is actually at a very low level. The problem is that the PCI tries to shoehorn not only populism, but also the development of different national situations, into a pre-established mould, into finished schemas, fixed and "invariant" (to use its own term) without integrating them into the least framework of analysis nor grasping the reality of a movement. There is an incapacity of the PCI to provide a lucid analysis of reality.

Why do we attach so much importance to the necessity of better understanding the phenomenon of populism? Because in this debate where divergences could be taken for simple, Byzantine quarrels, a discussion in the coffee shop or a debate between "intellectual circles", it is essentially a question for revolutionary organisations to methodically draw out the clearest vision of the stakes, the dynamic and evolution of capitalism in order to better arm the proletariat in its class combat.

To be continued...

CB, December 28 2017

[i] We refer the reader to their article: Bilan of the presidential elections: restructuring of the bourgeois political theatre in order to better defend capitalism, Le Proletaire, no. 524, May/June 2017.

[ii] See our article on The workers' aristocracy: a sociological theory to divide the working class, in the International Review no. 25 (1981).

[iii] Trump and his son-in-law, Jared Kushner appears to have encouraged de-facto Saudi ruler, Prince Mohammed bin Salman, in his destabilising adventures in the Middle East, particularly his hostilities against Qatar which go directly against US military interests. Similarly in Britain, Brexit-supporting foreign minister Priti Patel on "holiday" in Israel not only broke with British foreign policy but attempted to reverse it without the Foreign Office knowing. Prime Minister May's hesitation in sacking her showed just how weak she was.

Political currents and reference:

Rubric:

Trotsky’s History of the Russian Revolution (volumes 1, 2 & 3): an appraisal

- 1211 reads

ICC introduction

A number of comrades have been reflecting seriously on the importance of the October Revolution in Russia. The text that follows has been sent to us by a close sympathiser of the ICC in Belgium. The comrade had prepared this contribution for a previous meeting in September 2017 in Belgium on the topic of the October Revolution – we have already published a contribution by another sympathiser written at the same time (see Contribution to the discussion of the centenary of the Russian Revolution of 1917, November 2017).

We are publishing these contributions in the hope that as many comrades as possible will read them and that they will stimulate further reflection and discussion. We encourage all our readers to consider making further contributions themselves, either in the form of texts or participating on our forum at our website.

The text aims to draw the lessons from the revolution in Russia for today and the comrade takes a closer look to how Trotsky’s three-volume History of the Russian Revolution can help us in applying the lessons of this experience in the twenty first century. The contribution discusses what it means for communists to make up a balance sheet of a movement, a theory, an author, etc. – and how this can help us to reconsider our tasks today. Drawing a balance sheet, like any theoretical work, has as its goal to create the conditions for overcoming our weaknesses and give us the strength we need to struggle.

As the author concludes: “Reviewing a work of this magnitude is part of drawing a larger balance sheet. But it cannot be seen as an isolated event, a chapter that we have now closed. Only discussion amongst the revolutionary minorities and inside the proletariat can ultimately help us understand our predicament today. We do not live at the turn of the 20th century and much has changed during the last century. Some experiences have been vital, but all in all, the proletariat has lost more than it has gained. We can only hope that future struggles will provide new experiences that will allow us to overcome capitalism”.

We are in complete agreement with the text as a whole, but in the paragraph on the Kornilov coup and the United Front, towards the end of the article, there is a passage that gives the idea that Kerensky was merely an opportunist at the time, when in reality he was the head of the bourgeois government that was continuing the war effort and aimed to liquidate the revolutionary movement. So the reference in this paragraph to “compromise with opportunists” as a tactic in certain circumstances seems rather ambiguous. There is an article on the ICC website that we think clarifies this issue, pointing out that the Bolsheviks called for support to the workers’ militias and other class organs, not for support to the Kerensky government: ‘The Kornilov coup, August 1917: military blocs or autonomous class struggle?’( https://en.internationalism.org/wr/306/1917-Kornilov [34]).

In the centenary of the Russian Revolution the reaction of the bourgeoisie and its political and intellectual representatives has generally been twofold. On the one hand, especially from the left wing of bourgeois democracy, we are told that the Russian Revolution was one of the most singular, liberating events in history, and yet, at the same time, that “October” never died but lives on in the parties that claim historical ties to the Bolsheviks. In other words, to honour the Russian Revolution means to pay homage to the subsequent Soviet Union and the various extreme left groups of Trotskyist, Stalinist, Maoist and other varieties. In practice, all these different flavours of leftism invariably end up to be some variant of fervent red flag waving social democracy, different state capitalisms distinguished only by a preference either for the “democratic” form or for coming “from the barrel of a gun” [35]. To be clear on the matter, we believe that the “positions” of these bourgeois parties, which have nothing to do with the historical positions of the Bolsheviks, have only legitimized brutal state capitalist regimes in the name of communism.

On the other hand, it has been held by conservative and liberal thinkers that the Russian Revolution had to end in political repression and economic stagnation. In other words, the uprising of the proletariat in Russia must be held as monstrous from its very inception, because it had to lead to Stalin’s dictatorship and his brutal betrayal of the revolution. It is interesting how few authors of this vulgar-teleological type are willing to use this kind of reasoning to say something about capitalism and the First World War. Other, more “sophisticated” histories of the Russian Revolution use more developed conceptual frameworks. For instance, the “Russian character” is used to demonstrate that it had to be expected that a dictatorial regime had to eventually rise in Russia - see, for example, the recent biography of Stalin published by Prof. Dr. Kotkin [36]. An actual sociological explanation for the rise of Stalin and the state capitalist regime that bears his name, such as the isolation of the backward Soviet Union after the failure of the expansion of the communist revolutions to expand to Germany (1918), Hungary (1919) and other countries, is generally brushed aside. According to these gentlemen and gentleladies, such ideas must be dismissed as speculation and ideological babble. In the end, most of these authors tend to assume that the cause of the decline of the Soviet Union after a short revolutionary, progressive period was the return of the never-changing political struggle for “power”. In other words, according to these learned idiots, the historical significance of the Russian Revolution is that it replaced Czar Nicholas II with General Secretary Stalin.

In this review, I wish to first draw up a short balance sheet of twentieth century “communism” and the “official” story about the Russian Revolution. Then, I will ask the question how the three volumes by Trotsky can aid us in bringing back the proletarian movement in the twenty first century. Then, I take up some issues with Trotsky’s approach to the events and the Russian Revolution in general. Finally, I discuss what it means for communists to make up a balance sheet of a movement, a theory, an author, et cetera – and how this can help us to reconsider our tasks today.

I would argue that to even begin to contextualise the Russian Revolution means to draw an honest and clear balance sheet of the twentieth century. We must break with much of the intellectual garbage that has been strewn on the road to understanding what “communism” means.

After the decomposition of the Russian Revolution under the influence of the failed world revolution, the proletarian movement went into a steep decline, both theoretical and organizational. The state emerging from the proletarian revolution deformed to a state capitalist regime because it had to trade on a world market to survive. In the end, all those who resisted the new capitalist bureaucratic elite were silenced and finally murdered. The so-called ‘Communist’ movements and parties in Europa, Asia, Africa and South America, which took centre stage in twentieth century geopolitics, were nothing more than alternative bourgeois elites supported by the capitalist regimes in Moscow, Beijing or Havana. If these parties or movements were ultimately victorious in their struggle against other fractions of the bourgeoisie, they founded their own state capitalist regimes with material and ideological support from the Eastern bloc, enjoying similar despotic benefits as the political and economic elites in the Soviet Union.

Today, there is no communist party and the few groups of revolutionaries are small and have no real influence within the proletariat. Communist politics has been in a steady stagnation for almost eighty years. Despite the powerlessness of communist politics, the proletariat has had some important moments of resurgence since the end of the Second World War. So, despite all odds, the working class has not yet been defeated. But neither has the bourgeoisie yielded. The rule of capital continues to ravage our lives and holds the futures of our children to a kind of permanent ransom. The continuing civil wars in Syria and Iraq, climate change, racism, hatred of minorities: all these small and large horrors of our time, new and persisting, cannot be understood without the drive to keep the working class divided, to accumulate at all costs, to divide and conquer markets.

It remains to be seen if movements will arise that will be able to break with bourgeois ideology, whether such movements will be able to dispel the illusions of leftism. And more importantly, it remains to be seen whether the revolutionary minorities will be able to find the momentum to rebuild a revolutionary and proletarian party on a world scale when the moment arrives.

Trotsky’s History

How can an almost 100-year-old historical work aid us in rediscovering the foundations for a struggle of the class in our times? In other words, how do the three volumes by the famous Russian revolutionary Trotsky help us in recovering the “lessons of October [37]”, in other words, the lessons of the Russian Revolution?

The importance of Trotsky’s work lies with the centrality of the Russian Revolution to the imagination of the non-communist majority when communism is mentioned, discussed or in any other way touched upon. The Russian Revolution is consciously or unconsciously held to be the only example of a proletarian revolution, although any serious survey of the last century tells a rather different story. Similar proletarian revolutions and revolts inspired by the Russian Revolution took place in developed countries like Germany (1918), Hungary (1919), and many other countries worldwide. In the case of the German Revolution, the proletariat was able to maintain its struggle for power for almost a year. The Russian Revolution was nevertheless the only revolution in which the proletariat could hold state power despite the bourgeois forces opposing it in the February-November 1917 period of dual power[1] and in the subsequent Civil War-period (1917-1922). Thus, it is also the only revolution that the bourgeoisie and its army of intellectuals have to deal with, while the other revolutions are ignored, belittled or blatantly erased. And as we have already noted, because the Russian Revolution was so completely derailed owing to its isolation from the proletariat of the industrialized core of the world, the Russian Revolution also invites us to talk about communism in the negative, dismissive manner that is constantly rewarded by the bourgeois intellectual circles and academia.

It is precisely here that Trotsky’s work allows for a critical reassessment of the Russian Revolution. In addition to the available historical sources of the Russian Revolution and his own experiences, Trotsky not only uses numerous eyewitness accounts of his allies, but also of his foes. In doing this, he brings forward the entirety of the truth without becoming apolitical or irrelevant. The three volumes deal chronologically with the various events and figures of the Russian Revolution leading up to the proletarian bid for power in February 1917 and the final dismantling of the bourgeois state in October of 1917. Both singular volumes and an abridged version of the three volumes are available for free on marxists.org in different digital formats (pdf, epub, …). The collected three volumes can also be bought at a relatively cheap price (45 dollars) in a new abridged, hardcover edition from the North America-based publisher Haymarket Books, that has been somewhat promoted in light of the centenary of the Russian Revolution.[2]

It is without a doubt a lengthy work that requires one’s full attention if one is to grasp the totality of the subject studied. Trotsky simply does not summarize, he enumerates, contextualizes, in other words, explains. There can be no doubt that the different events and dramatis personae can be confusing at times and sometimes the author seems to assume that his audience will simply understand after a first or second mention. Trotsky himself is aware of the wide, multi-faceted scope of his work and addresses the issue by criticizing some of the assumptions about what good writing means: