ICConline - 2018

- 1154 reads

January 2018

- 735 reads

Demonstrations in Iran: strengths and limits of the movement

- 1257 reads

On 28 December, the first sparks of a movement which brought to mind the “Arab Spring” of a few years ago began to shake the territory of Iran. The movement seems for the moment to have run out of steam as we write, although we are seeing other expressions of anger against the deterioration of living standards, such as in Morocco, Sudan and above all Tunisia.

A spontaneous explosion of anger

Iran is a country with powerful imperialist ambitions, where military expenses devoted to intervention throughout the Middle East have risen sharply. Although Iran is still suffering from the sanctions imposed by the USA, it has spent huge amounts of money in the war in Yemen, in supporting Hezbollah and the Assad regime, and its own armed gangs operating at the international level. And it has built up its stock of arms against Saudi Arabia. All this has meant austerity for the population. In a context marked by disappointed hopes in the wake of the deal over nuclear weapons agreed with the Obama administration, the economic crisis, aggravated by the international sanctions and the corruption of the regime, has plunged the majority of the population into poverty and uncertainty. For months now there have been demonstrations of discontent by pensioners, the unemployed (28% of young people are out of work), teachers, workers whose wages aren’t being paid. Finally, the 50% rise in oil and basic foods, like the doubling of the price of eggs - there has been talk of a “revolution of the eggs” – lit the fuse. The movement erupted in Mashhad, the second biggest city, in the north east, and quickly spread to the capital Tehran and all the main urban centres: north to Rasht and south towards Chabahar. In all the crowds openly rejecting the policies of the state, the working class was present, even if somewhat diluted in the rest of the demonstrators: factory workers, teachers, many unemployed especially young people: they were all there. Also many students. It is also significant that a large number of the demonstrators were women.

At the same time, despite the courage and fighting spirit of the protesters, the working class was not able to provide a real orientation to this struggle, was not able to affirm itself as an autonomous political force. And this was the case even if a minority among the students, notably in Tehran, came out against the reactionary nationalist slogan “neither Gaza or Lebanon, I will only die for Iran” with an expression of real proletarian internationalism: “From Gaza to Iran, down with the exploiters”. These elements also called for workers’ councils and rejected any idea of being dragged into the battle between the “reformist” and “hard-line” bourgeois cliques[1]. Such attitudes really scared the authorities and the students were particularly targeted in the arrests. And in general, despite the weight of democratic illusions and other political weaknesses, the bourgeoisie was extremely worried about this “leaderless” explosion of anger. The Supreme Leader Khameini was silent for some time and president Rouhani was more cautious than firm. The government even announced that the rise in fuel prices would be cancelled. It’s true that symbols of the political and religious authorities were targeted and in some cases burned down: banks, public buildings, religious centres and above all the HQ of the Revolutionary Guards, the regime’s militias. Violent clashes with the police led not only to arrests but to a number of deaths. Bit by bit the tone of the authorities, and their reaction, grew firmer. Rouhani and Khameini announced that violence and illegal actions by “troublemakers” would be severely punished. They accused the demonstrators of being “enemies of Iran”, of being in league with foreign powers, in particular the USA and Saudi Arabia.

And indeed, on the social networks like Twitter, many of the hashtags calling for demonstrations originated in Saudi; similarly, the Mujahadin organisation based in Paris, opposed to the Iranian regime and close to the Saudis, declared its support for the demonstrations. And of course, Trump with his provocative statements and the other rival powers want a weakened Iran. But this was a movement that has its origins inside Iran. Taking advantage of the movement’s lack of perspective, the regime could prepare the ground for repression. It mounted counter-demonstrations supporting the regime and its ayatollah, shouting slogans like “Death to America” and “Death to Israel” and denouncing “sedition”. The head of state could play on these divisions and announce that the alternative was “us or chaos”. By evoking the tragedy which followed the original protests in Syria and elsewhere, the leadership was clearly threatening the demonstrators, insinuating that their movement could only result in a similar chaos and bloodshed.

The difficulties of the proletariat in Iran

This spontaneous social movement is the most important since the social crisis of 2009, the year of the “Green movement”. At this time, there was a real danger of the proletariat being caught in the crossfire between competing bourgeois cliques. As we wrote at the time:

“Opposing the bloody, corrupt elements around Ahmadinajad, we see people who resemble them like two drops of water. They are also in favour of an Islamic Republic and for building the Iranian atomic bomb. All these people are basically the same because they all stand for their own personal and nationalist interests”

Today, much more than in 2009, the movement is a real expression of the exploited and the disinherited themselves, but it is without a clear proletarian orientation, apart from a few minorities. The struggles of the proletariat in Iran have without doubt been part of the struggles of the world proletariat since the 1960s, especially in the oil industry, transport, education and so on, but even when the struggles reached their high point in 1978-79, when they precipitated the fall of the Shah, the political weaknesses of the proletariat made it possible for a horde of religious fanatics led by the Ayatollah Khomeini, supported by the Stalinists and other left nationalists, to install themselves in power. Brutal repression came in the wake of the “Islamic Revolution”. Many militant workers were executed for taking part in strikes under the regime of the mullahs. The proletariat was also subjected to the terrible war between Iran and Iraq between 1980 and 1988, which left millions dead.

Since then, there have again been some important struggles, such as during the year 2007 when 100,000 teachers came out in solidarity with the factory workers, but the underlying difficulties remain today. Despite a very strong fighting spirit, and the fact that the current movement was based on economic demands which are part of any proletarian struggle, the movement has waned because of a lack of a real class identity and perspective. At the same time, the workers are still very much faced with the permanent rivalry of different bourgeois factions, and there is a real danger of the class being dragged behind one or the other[2]. On top of this, Iran is surrounded by countries at war which makes it very difficult for the workers of Iran to win the solidarity of the proletariat in these countries and strengthens nationalism within their own ranks.

But in a more profound sense, the weaknesses of the proletariat in Iran are above all those of the world proletariat, since even in the most experienced sectors of the class we are seeing a serious loss of class identity, and above all a loss of perspective that would give a real meaning and direction to the class struggle.

Nevertheless, the bravery and militancy of the demonstrators in Iran should be an encouragement to workers of the world. Fighting against austerity, raising demands in defence of our economic interests, this remains essential if the class struggle is to again raise its head. But the real solidarity with our class brothers and sisters in Iran consists in reviving and consciously taking charge of our own struggle, not only against austerity but against the capitalist system as a whole.

WH (5 january)

[2] See our online article ‘Iran: the struggle between bourgeois cliques is a danger for the working class’

Rubric:

Iran: the struggle between bourgeois cliques is a danger for the working class

- 1109 reads

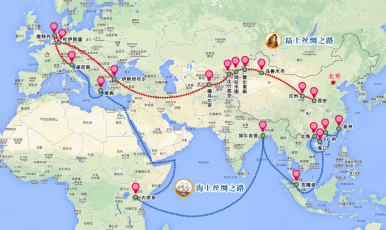

As we show in our article ‘Demonstrations in Iran, strengths and limits of the movement’, although there are promising signs of working class resilience, the danger is very real, not only of bloody repression, but also of the manipulation of the popular anger by the different fractions of the ruling class. The old conflict between “reformers” and “hard-liners” within the “Islamic Republic” has entered a new stage. The reformers around president Rouhani are convinced that a major policy change is necessary in order to consolidate the considerable gains made by Iran in recent times. These advances have taken place essentially at two levels. At the level of foreign policy, the Shia militias and other forces supported by Tehran have made important advances in Iraq, Syria and the Lebanon (the so-called revolutionary sickle from Iran to the Mediterranean) and in Yemen. At the diplomatic level, the regime was able to make an “atomic deal” with the major powers, leading to the lifting of certain economic sanctions (in exchange for a formal renunciation of acquiring an Iranian atomic bomb). Today these advances are menaced from a number of sides. One of them is the alliance against Iran which the USA under Trump is trying to construct around Israel and Saudi Arabia. Another is the economic situation. Unlike at the military or diplomatic level, Iranian capitalism has made no economic progress in recent years. The contrary is the case. The economy is groaning under the cost of the operations of Iranian imperialism abroad, and weakened by the international sanctions. The United States has failed to lift economic sanctions against Iran as it had promised as part of the nuclear agreement. Instead, it has been obstructing the engagement of European companies in Iran. Now, under Trump, the US sanctions will even be reinforced. Another central problem is that the competitiveness of the Iranian national capital is being strangled by the highly anachronistic theocratic-clerical bureaucracy, which has no idea how to run a modern capitalist economy, and by the kleptomaniac system of the “Revolutionary Guards”. From the point of view of president Rouhani, breaking or at least curbing the dominance of these structures would be in the best interest of Iranian capitalism. It would also give Iran a more liberal image, better suited to countering the sanctions, the diplomacy and the rhetoric of its enemies abroad.

But on account of the dominant position of the hardliners within the armed forces, the reformers have few legal means at their disposal to put through their policy. This is why president Rouhani began to call on the population at large to formulate its own critique of the present economic policy, and of the corruption of the Guards and their business interests. The reformers were trying to use popular discontent as a lever against the hardliners. Such a hazardous policy reveals the backwardness and lack of suppleness of the ruling class in Iran, which is unable to settle the conflicts in its own ranks internally. It was all the more hazardous when one considers that Rouhani was perfectly aware of the popular disappointment once the promised economic boom which was supposed to follow the lifting of sanctions failed to materialise. Moreover, Rouhani was apparently not the only one taking chances. The president himself has accused his hardline opponents of having organised the first demonstration in Mashhad, which is the bastion of Ibrahim Raisi, the candidate of the hardliners in the presidential elections last May. The main slogan of this demonstration is indeed reported to have been “death to Rouhani”. But as soon as the protests extended, other slogans were heard such as “death to Khamenei” (the religious hard-line head of state), “down with the dictatorship”, or “What is free in Iran? Thievery and injustice!” The appearance of such slogans directed against the regime as a whole indicates that neither of the two main bourgeois fractions is able to manipulate the popular anger at will against the other.

This however in no way lessens the danger of the working people being manipulated by the ruling class. It is important, in this respect, to remember what happened in Egypt, where popular protest (“Tahrir Square”) involving mass meetings and demonstrations, but also workers’ strikes, swept away the Mubarak regime. This was at the beginning of the “Arab Spring”. But this was only possible because the military let it happen (president Mubarak intended to curb the influence of the generals on politics and above all in the economy). In Iran (as in Egypt at the time) foreign powers were also involved. The claim of the clerical leaders in Tehran today that the protests in Iran have been instigated by foreign powers (USA, Israel, Saudi Arabia) has enraged wide sectors of the population, since these claims arrogantly deny both their very real suffering and their ability to take the initiative themselves. This does not mean, however, that these and other rival powers are not trying to destabilise the Iranian regime. In an interview given in April of last year, the Saudi crown prince Bin Salman declared that the conflict between his country and its Persian neighbour would be fought out “in Iran, not in Saudi Arabia”. One of his think-tanks in Riyadh has been advising him to stir up discontent within the Sunni religious minority in Iran, as well as among ethnic minorities (one third of the population of Iran are not Persian). In Egypt, after the fall of Mubarak, a civil war between the two main fractions of the bourgeoisie – the armed forces and the Muslim Brotherhood – was only averted through the ferocious repression of the latter by the former. In Syria, the social protests triggered off an imperialist war which is still raging. Whether in Egypt, Syria or Iran, the working class is not only relatively weak, it is also internationally isolated on account of the present reflux of class struggle, class consciousness and class identity at a world scale. Without the support of the world proletariat, difficulties and dangers for our class sisters and brothers in Iran are all the greater.

Steinklopfer. 9.1.2018.

Geographical:

- Iran [3]

Rubric:

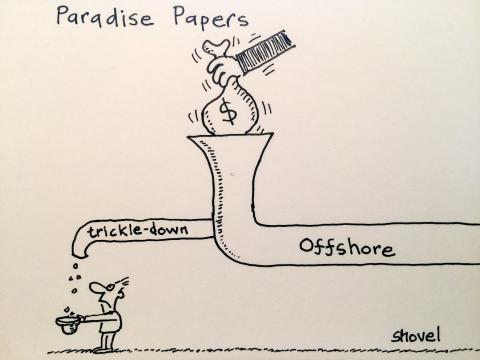

Paradise Papers: an ideological campaign in the service of the capitalist state

- 942 reads

Just over a year ago, the bourgeois class launched an ideological campaign around the Panama Papers. Loud publicity was given to a blacklist of fiscal havens. It was billed as the discovery of a series of murky networks and geographical areas, outside any legal controls, where enormous amounts of capital are being stashed. As it happens this is a song we have been hearing a lot since the phase of acute economic crisis opened up in 2008-9.

But now it’s all starting again! A new ideological campaign has been launched and all the bourgeois media are involved. This time they are talking about the Paradise Papers. All kinds of personalities are involved: politicians, businessmen, sports and entertainment stars. Queen Elizabeth the Second herself has not escaped the scandal. The bourgeois media and a good number of states are apparently being infected by a new virus which is obliging them to seek for truth, morality and fairness.

An ideological campaign against the proletariat

The state and the media cry about injustice: certain rich people don’t want to pay the taxes they owe to the national collective, to the state! Even some of the biggest global companies are evading their taxes! This is theft pure and simple! And in contrast to this, most of us, even when our wages hardly allow us to survive, are paying our taxes in full…

The left of capital has a particular role to play in all this. In France, it’s Mélenchon’s party, La France Insoumise, which shouts the loudest and proclaims that it is scandalised. Their slogan is simple: “make the rich pay, not the poor!”. All the leftist parties are on the same wavelength: The NPA (New Anti-Capitalist Party) and Lutte Ouvrière also join in the refrain. If the state was doing its job, none of this would be going on. There would be more money for hospitals, schools and all the other public services. In fact these arguments are not very different from what the government itself is saying. It’s the same story in all the developed countries.

A basic law we’ve learned from the history of capitalism is that you should never take the declarations of the ruling class and its media at face value. So what is being hidden behind this deafening chorus, this demand that the cheats and thieves be caught and punished? That the rich should pay what they owe and that that no one should escape from “equality before the Tax”? What’s the reality behind all this, and what do these fiscal “paradises”, these tax havens, really represent?

Tax havens: a world-wide reality linked to state capitalism

A tax haven is a country, a part of a country, or an organism where, usually quite legally, money can be stashed with impunity. Little or no tax is paid and no questions are asked about where the invested capital comes from. There are thousands of such tax havens around the world. And they are not only to be found in more or less exotic places like the Virgin Islands or Bermuda. Nor are they limited to the small states we hear about so much in the media, such as Luxemburg, Malta or Ireland. In fact the leading tax haven in the world is the City of London. London’s financial district is the centre of a spider’s web connected to any number of offshore tax havens. In other words, the capital amassing in the parallel circuits of the tax havens comes here to be invested. The biggest banks in the world, such as the HSBC and their shadowy agencies (the “back banks”), the most powerful investment funds and the world’s leading companies use these networks to circulate a large part of their capital. Money from drugs, prostitution, arms sales, floods all these networks. Reality is very far from the picture painted by the media, who focus on this or that celebrity hiding their dough in Swiss banks. This is a whole system, managed by the states themselves. One of the essential features of decadent capitalism is the concentration of capital in the hands of the nation state, which has become the entity around which the national capital organises its struggle, both against the proletariat and against other national capitals. States are not the dupes of multinational companies who escape the rules laid down for the operation of the world market. On the contrary, they are the main protagonists on these markets and in the final instance they are in control of the banks and the companies. Despite appearances, above even the most powerful banks and multinationals, the public authority of the state takes precedence. Multinational firms like Exxon, General Motors or Apple are always closely tied to the state, whether through public investments, the nomination of directors and so on. “Contrary to an opinion often expressed, by acting as the impetus for truly innovative projects, the public organisms (public investment banks and others) don’t push out the banks or private firms. They do what the latter don’t do or can’t do. Far from being victims of exclusion, the private enterprises could not develop if the state didn’t prepare the ground for them by making investments, notably in key research, which they could not do either financially or ‘strategically’”[1]. For a state, the big multinationals which are linked to it often represent a strategic sector of the national economy. This doesn’t mean that the private interests of these enterprises or banks always coincide exactly with those of the state. The quest for “tax optimisation” or the hunt for tax fraud are very current illustrations of this. But in the world’s financial markets and stock exchanges, the authority of the state remains a preponderant one. For example, the Euronext fusion of the stock exchanges of Paris, Bruxelles and Amsterdam openly depends on public financial authorities such as the Autorité des Marches Financiers in France or the Autorité Européene des Valeurs Mobilières. These state organs survey, control and can even sanction private enterprises. Here again, the interests of private operators can often come up against those of the state, but they can’t completely escape its control.

Despite the efforts at regulation, states have permitted an exponential development of what’s called the “little by little” market[2], which paradoxically makes activities and operators more opaque. This parallel market is mainly reserved for the very big investors (precisely the ones most closely linked to the state), those whose exchanges are measured in billions. More than 50% of these transactions, a good part of them highly dubious, take place at financial centres like the City or Wall Street. And the actors are not exactly unknowns: JP Morgan Chase, Goldman Sachs, Barclays Capital, etc. We should also add that central banks like the European Central Bank or the FED are key players as well.

While the finger is most often pointed at the more exotic tax havens, the World Bank stresses that “the financial systems of developing countries have less depth and a more limited access than those of the developed countries”. In short, the essential job of tax evasion or “optimisation” by the grand conglomerates, acting behind a myriad of screening companies, gets done in the “domicile”. All states encourage the formation of “offshore” resources under their aegis. The tax havens are largely dependent on the big countries, who use them to attract foreign investment as well as to avoid too great a flight towards tax havens controlled by other states, or which remain more or less out of their own control. Thus, France’s favoured tax haven is the Principality of Monaco. Britain has the Channel Islands, the USA has the Bahamas or the state of Delaware, Austria and Germany have Liechtenstein. The list goes on. But more than this, states have their own investment funds destined for these parallel circuits. On 11 November 2017, the Belgian Finances Minister Johan Owerdeveldt declared that he would endeavour to make sure in the future that the state would not support investments in tax havens via the Belgian investment society which is 64% owned by the state. All this is sheer hypocrisy, theatrical speeches that have been going on for years while nothing really changes. And for good reason. Since the 1980s, the proliferation of tax havens has become a very widespread phenomenon. They would not have been able to play such a key role in the world economy if, under the guidance of the major states, there had not been so much deregulation of finance. Since then finance capital has assumed gigantic proportions across the entire planet. It is this form of capital which has become so necessary for the state itself to maintain capitalist accumulation. The search for ever-growing investment and profit has brought about an evolution in state capitalist policy on a global scale. It is this process which lies at the roots of the possibility and necessity to develop this network of tax havens to drain off a large part of liquidity. Thus Business Bourse on 18 November 2017 wrote: “the evil given the name of tax havens function like the brothels of capitalism. You do dirty business which can’t be publicly recognised but is indispensable to the functioning of the system. Like houses of ill repute in traditional society”. The Paradise Papers, like the Panama Papers, were uncovered and made public by investigative journalists who belong to 96 of the most important newspapers in the world. The leading papers in the western world are all included. In Britain, it’s The Guardian. In France, it’s Le Monde. The bourgeois press seems to be on the trail of the tax evaders. But here again the orchestra is being conducted by the capitalist state. All this investigative journalism is tied to the interests of the national economy and the states which present themselves as the guarantors of social justice and as the victims of “financial gangsters” and “greedy bankers”.

Tax havens: cogs of the capitalist economy in crisis

Tax havens have taken on a powerful weight in the reality of world commerce. Two thirds of Hedge Funds, speculative investment funds, are domiciled in tax havens and play a key role in investments in production and the financial sector. More than 40% of profits from the big global companies and banks end up in tax havens. Already in 2008, just after the appearance of the open crisis, 35% of financial flows were passing through these offshore locations. But even more significant is the fact that 55% of international trade depended directly on these flows of capital. And this tendency has increased exponentially since then.

A better control over the tax havens: a necessity for all capitalist states

A question is posed: why are the capitalist states now orchestrating this huge media campaign? It is well known that capitalist nations and their states are weighed down by global debt. True, not all of them to the same degree. Germany, for example, is a relative exception. But the USA, Japan, the other countries of Europe, all are experiencing dizzying levels of debt. And China has become a leading model in this trend. The capitalist economy has an imperious need for tax havens today, but capitalist states are desperate for funds. The finances of the central banks are not sufficient to bear the weight of state debts, so that governments have a real need for tax revenue at a time when a large part of such revenue is escaping them thanks to the tax havens. In July 2012 the “independent” foundation Réseau pour la Justice Fiscal published a study on tax havens and estimated that tax evasion accounts for 25,500 billion euros, more than the combined GNP of the US and Japan. This comes at a time when every big state has to increase its military expenses to face up to the spread of imperialist war around the world, and to deal with an explosion of unemployment and poverty. While each state is trying by all possible means to reduce the benefits conceded to the sectors of the proletariat who have been ejected from work, this also involves maintaining an increasingly expensive police control over these sectors and the population as whole. So behind the international ideological campaign around the Paradise Papers we can find a ferocious fiscal competition. As much as possible, states must prevent their rivals from attracting capital to the tax havens within their sphere of influence and thus allowing companies to avoid paying taxes in the countries where their profits are being made. In other words, in every country state capitalism is stepping up the trade war. Behind these famous “discoveries” by the so-called “independent” inquiries by all the big newspapers we can discern the demands of capitalism in crisis. Along with the need to get their hands on liquidities and deal with tax fraud, the capitalist states are above all trying to get a better control over the companies acting in their sphere of influence, and this means regulating the obscure world of finances at some level. The big international organisms have been trying to do this for some time, especially in the mid-90s:

“Following the Group of Seven summit in Halifax in 1995, a series of initiatives aimed at a better functioning of financial markets was launched, to a large extent under the auspices of the International Monetary Fund and the Bank of International Settlements. These had the object of improving transparency and the way that financial and economic data is divulged, of strengthening surveillance of national and international financial systems and putting in place mechanisms of support for periods of crisis and providing training in the supervision of the finance sector”[3]

Despite the measures taken, the reality of the economic crisis, the short-term vision and irresponsible policies of certain private or even public operators, and the overall trend towards every man for himself - all this has increased the danger of a fragmentation of trade and of the world economy. The endless scandals like the Panama Papers and the Paradise Papers, blown up by the media, serve to underline the need for greater control by the state, the need to rein in those who flout discipline and work in the shadows to the detriment of the economic needs of the major states. As we can see from the whole history of the complex and fragile efforts to keep finance under control, tax havens will still be useful and are not going to disappear. But the state has to remain the chief gangster, retain the monopoly of a whole mass of capital which could escape its control if it doesn’t act firmly. This is all the more true at a time when corruption, “affairs” and what the bourgeoisie prudishly calls “conflicts of interests” are becoming more and more commonplace, undermining the higher interests of the state. The height of hypocrisy is that it is the heads of government themselves who are often the leading tax cheats and specialists in “tax optimisation”. Among the revelations in the Paradise Papers, let’s not forget all the politicians who are often the most zealous defenders of austerity and of anti-working class measures[4].

The working class has nothing to gain from increasing regulations on tax havens

Capitalism in crisis breeds both tax havens and attempts to regulate them. Just as it breeds more and more unemployment, insecure jobs, and poverty. This degradation of working class living standards has nothing to do with whether tax havens are regulated or not. It’s in capitalism’s interest to make a profit from the exploitation of the working class. A worker who doesn’t add to the growth of capital is a useless commodity that is maintained at the lowest price in order to preserve social peace. It’s an unprofitable mouth to feed and the mass of workers without work is rising inexorably. Given the level of state debt today, a bit of extra tax revenue isn’t going to solve the growing budgetary difficulties. Only a reduction in what the bourgeoisie calls “social spending” is on the agenda. Behind a supposed moralisation of capitalism, the so-called struggle against tax paradises and fraud, the real future of this system is the accelerating decline of every aspect of proletarian living conditions.

Stephen, 28.12.17

[1] L’État conserve un role majeur dans l’innovation’, Le Monde, 27.1.14

[2] On a “little by little” market, transactions are concluded directly between buyer and seller, without any commission to the stock exchange through which the transaction takes place

[3] ‘The globalisation of financial markets and monetary policy’, a speech by Gordon Thiessen, a former governor of the Bank of Canada

[4] A few names revealed in the Panama and Paradise papers:

- The American Secretary of Trade, close to Donald Trump

- The former Tory treasurer Michael Ashcroft

- The Icelandic Prime Minister Gunlausson

- In Brazil, the ministers of the Economy and Agrculture, Henrique Meirelles and Blairo Maggi

- The Argentine president Mauricio Macri

- A close associate of Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau

- Ian Cameron, the father of David Cameron

- A number of Russian oligarchs close to the Kremlin

- The business lawyer Arnaud Claude, associated with the former president of the Republic in the Sarkozy cabinet

Rubric:

February 2018

- 656 reads

On Marx and Epicurus

- 4088 reads

Under the heading ‘Readers’ Contributions’ we aim to encourage our readers and sympathisers to write texts and articles which can go into greater depth than is possible in our discussion forum, and so stimulate a longer term reflection. These articles, while being broadly based on proletarian politics, need not fully represent the positions of the ICC, or may deal with issues on which the ICC does not have a collective view.

Some notes on elements of Marx's 1841 doctoral thesis on The Difference Between the Democritean and Epicurean Philosophy of Nature and the profundity of the Epicurean "swerve"

Given the fragments, literally, of the works of Epicurus available to Marx at the time, the materialist analysis that he manages to develop from them is pretty amazing. After Marx's demise much more evidence of Epicurus' philosophy has been found: on charcoal remains of papyri in Philodemus' library in Herculeum, on the wall of Diogenes of Oenoanda and writings kept in the Vatican for whom Epicurus was strictly taboo. The mere mention of Epicurus (or Lucretius) led to torture or imprisonment by the Inquisition in Naples and all of their followers were consigned to the Sixth Circle of Hell. Marx was also assisted in this work on Epicurus by the poem On the Nature of Things and works of the aforementioned Roman poet Lucretius.

Titus Lucretius Carus was a great influence on the sixteenth century Italian materialist Giambattista Vico, and an even bigger influence on the workers' movement. He developed the idea of descent with modification, and understood that energy could neither be created nor destroyed. His poem was the basis for Lewis Henry Morgan's great work, Ancient Society... and thus Engel's work The Origin of the Family Private Property and the State. He laid out the tenets and philosophy of Epicurus in his poem. The renowned Epicurean scholar, Cyril Bailey who translated his work into English, said in 1928: "Looking back on his (Marx's) work now it is almost astonishing to see how far he got considering the materials then available and he was probably the first person to see the true distinction between the Democritean and Epicurean systems". And to a large part he did this by focusing on the meaning of the Epicurean swerve.

Epicurus' study of the atom allowed him to delve into "the nature of human sensation and existence". Benjamin Farrington, noted scholar of Greek philosophy, wrote: "Oddly enough it was Karl Marx in his doctoral thesis... who first took the measure of the problem and provided the solution... making Epicurus the deeper of the two (in comparison to Democritus) inasmuch as he laboured to find room in his system both for animate and inanimate being, both for nature and society, both for the phenomena of the external world and the demands of moral consciousness" (From Marx's Ecology, materialism and nature by John Bellamy Foster).

Epicurus' work removes the gods (almost entirely) and the fear and terror that they inspire in mortal man, opening the way for chance, possibilities and freedom: "That which is abstractly possible, which can be conceived constitutes no obstacle to the thinking subject, no limit, no stumbling-block". Continuing from this, only Marx could say from the fragments that he knew of: (that) "Epicurus therefore proceeds with boundless nonchalance in the explanation of separate physical phenomena" and this from the possibilities that brought them about. In contrast to Democritus, who also contributed to a materialist analysis, Epicurus posed the question of a tiny "swerve" in the atom against the straight, deterministic lines of the former. Cicero ridiculed this idea calling it "disgraceful" and said it was "entirely impossible" that the universe came about by "complexities, combinations and adhesions of the atoms one with another". Hegel suggested that he had nothing useful to say; similar criticisms were levelled against Epicurus by the 17th century French philosopher Pierre Bayle, but the strange reality of the quantum nature of the atom is now beyond doubt. Lucretius understood this: "... if the atoms never swerve so as to originate some new movement that will snap the bonds of fate" nothing would change, but this process does take place "in time unfixt, imperceptible to the senses and in the smallest possible space". The further relevance to quantum mechanics is evident. For Marx the swerve represents "the soul of the atom, the concept of abstract individuality".

Epicurus suggests qualities to the atom, size, shape and weight whose declination (swerve) opposes any determinism: (the atoms) "are therefore opposed to one another as immediate realities". Marx agrees with Lucretius, saying that "the declination breaks the fati doedra (bonds of fate)", and applied to consciousness "the declination is that something in its breast that can fight back and resist". The declination lifts the atom out of the domain of determinism. If atoms didn't swerve they could neither repel nor attract, and it's from this repulsion and attraction that, according to Epicurus with Marx: "the world of appearance emerges", appearance that is transformed by consciousness from essence. Repulsion and attraction go beyond Democritus' determinism, just as the swerve of the atom goes beyond the relative existence of atoms falling in fixed lines. Democritus assumes an infinite number of shapes of the atom up to infinite size. But according to Lucretius, "it is rather by a definite and finite number of shapes that the atoms are differentiated from one another", which is also another way of expressing the modern theory of the conservation of energy.

As for weight, in the view of Epicurus it exists only as a different weight and the atoms themselves are substantial "centres of gravity" with weight existing in respect of repulsion and attraction. In this way Epicurus anticipates the fact that all bodies, whatever their weight and mass, have the same velocity when they fall through space. Time is discussed by these Greeks in some ways similar to that of modern-day physicist Carlo Rovelli, and both Democritus and Epicurus agree that time is excluded from the atom. For the latter, infinite time exists within infinite space comprising infinite worlds, giving rise to free-will against superstition and fear of the gods. Following Epicurus, Lucretius writes: "... time by itself does not exist... It must not be claimed that anyone can sense time by itself apart from the movement of things or their restful immobility... accidents of matter, or of the place in which things happen". Marx calls this "the 'accidens' of accidens". Time is in opposition to space, time is change as change, and further for Marx, it is the "fire of essence" which can only be seen through reason: "... this reflection of appearance in itself which constitutes the concept of time, has its separate existence in the conscious sensuous. Human sensuousness is therefore embodied time, the existing reflection of the sensuous world itself".

There's a chapter called "The Meteors", by which Epicurus means all celestial bodies; and this is doubly important for the Greeks because their "philosophers worshipped their own minds in the celestial bodies" (like a "cult" according to Marx) and this was another factor in the elevation of the gods that Epicurus flatly rejected. Once the myth is removed from the heavens everything is possible, every explanation is sufficient. For example, there's not one explanation to a lightning strike but a number of interacting properties and reactions, and the task for Epicurus is to "trace their cause and banish the source of disturbance and dread". He takes comfort in the fact that everything is impermanent and unstable, not eternal and immortal. Marx says that Epicurus "in wrath and passionate violence" rejects those that propose one method of explanation of the Unique, Eternal and Divine in the heavenly bodies. The irregularity of orbits, the number of multiple possibilities involved in heavenly phenomena, the multitude of explanations is for Epicurus the road to calm, understanding and freedom. For Marx the contingency and freedom espoused by Epicurus, which before him was mechanical determinism, brought out the "active side".

Marx's materialism has strong roots in the swerve of Epicurus, showing that it could be an element in human emancipation from the material conditions of a world characterised by the development of human relations to its basic needs, from which consciousness develops. Chance and contingency play a part in this along with human ethical considerations. Marx wasn't uncritical of Epicurus since he was only interpreting the world, but his interpretation gave the world a direction and in the thesis Marx builds on some of his contradictions. He criticised his ideas of too many possibilities and his individualism but, again, these were part and parcel of the outcome. Engels, up to his death, was, enthusiastically with Marx all the way on the materialism of Epicurus. Engel's himself rejected much of bourgeois materialism in favour of the Greek "enlightenment", particularly Epicurus and Lucretius. He continued Marx's work on Epicurus and praised what he called the latter's "immanent dialectics". Epicurus recognised the estrangement of human beings from the human world in the shape of religion, now reinforced by the alienation of the labour-capital relationship, and had profound concerns about the well-being of the earth and the relationship of nature to man, points which Engels picked up and expanded on along with Marx.

A final quote from Marx in the thesis on Epicurus: "When human life lay grovelling in all men's sight, crushed to the earth under the deadweight of religion whose grim features loured menacingly upon mortals from the four quarters of the sky, a man of Greece was first to raise mortal eyes in defiance, first to stand erect and brave the challenge. Fables of the gods did not crush him, nor the lightning flash and growling menace of the sky.... Therefore religion in its turn lies crushed beneath his feet, and we by his triumph are lifted level with the skies.

The difference between Democritean and Epicurean philosophy of nature which we established at the end of the general section has been elaborated and confirmed in all domains of nature. In Epicurus therefore, atomistics with all its contradictions has been carried through and completed as the natural science of self-consciousness. This self-consciousness under the form of abstract individuality is an absolute principle.

Epicurus has thus carried atomistics to its final conclusion, which is its dissolution and conscious opposition to the universal. For

Democritus, on the other hand, the atom is only the general objective expression of the empirical investigation of nature as a whole.

Hence the atom remains for him a pure and abstract category, a hypothesis, the result of experience, not its active [energisches] principle. This hypothesis remains therefore without realisation, just as it plays no further part in determining the real investigation."

We are conscious now that far from being crushed, religion, particularly its fundamentalist versions in both east and west, has been fed and invigorated by decomposing capitalism. The task is to overcome this along with all the divisions that emanate from the breakdown of ruling class ideology and to this effect we have to salute the groundbreaking work of Marx on Epicurus.

Marx's appendix on Plutarch

At the end of Marx's dissertation is an appendix called: Critique of Plutarch's Polemic against the Theology of Epicurus, of which, like much of the latter's work, only fragments survive. Nevertheless, even here, Marx makes some significant points and looks at some new areas in these fragments that we can return to in the context of the whole. It's also worth remembering that this work of Marx developing on Epicurus showed his gradual independence from Hegel and demonstrated to him in the process the importance of religion and the unfolding necessity to try to develop a profound understanding of what religion meant for humanity and its emancipation, while contending that "No good for man lies outside himself".

For Plutarch, God was on the side of good against the wicked - the powerful nature of this aspect of religious ideology shouldn't be underestimated even to this day. Against Epicurus, Plutarch argued that if there was no God there was no joy or happiness. According to him, belief in God, as well as bringing relief from pain, fear and worry "indulges in a playful and merry inebriation, even in amatory matters!” Marx responds on the proof of God that gods are like imagined money - in the end there will be a price to pay. And anyway, proof of 'your' God is a disavowal of others and vice-versa. Plutarch divides society into the good, decent, intelligent and the bad and uncivilised whereas, according to Marx, Epicurus deals with the "essential relationship of the human soul in general". For Marx, Plutarch's objection to Epicurus' ungodly atomism poses the question of the eternal, unchangeable characteristics of man against those of change, free-will and self-consciousness. Plutarch's view of religion is based on the reform of the wicked by, first of all an animal-like fear and secondly, sentimentality: "There is no qualitative difference between this and the previous category. What in the first place appeared in the shape of an animal fear appears here in the shape of human fear, the form of sentiment. The content is the same" (Marx). After talking about sentiment Marx goes on to briefly talk about the "... naked, empirical ego, the love of self, the oldest love...".

Marx certainly has plenty of criticisms of Epicurus on the questions of mechanistics and "accidents" but wholly supports his view that events of human history are neither mere accidents nor merely arise out of necessity. Epicurus recognises and never denies necessity or subsistence but always insists that the bounds of both must be broken and this by the means of human reason and human consciousness.

In the dissertation Marx argues that Epicurus goes beyond the sceptical world of the Democratean atom and its "subjective semblance" by positing its "objective appearance". "Implicit in Epicurus' philosophy was the notion that knowledge both of the world of the atom (imperceptible to the senses) and of sensuous reality arose from the inner necessity of human reason embodied in abstract individuality and freedom (self-determination)." Marx's Ecology materialism and nature, John Bellamy Foster.

In his appendix on Plutarch Marx also takes aim at the German idealist philosopher Friedrich Schelling, whose positions degenerated into a defence of religion and from this a cock-eyed vision of nature. Schelling's appointment as Rector at the University of Berlin indicated the closing off of universities to the Young Hegelians and a definite turn by Marx into further profound applications of his work.

Marx took what was best about the enlightenment of Ancient Greece and defended and refined the analyses of Epicurus against the determinism of Democritus; and then he defended the materialism of the modern Enlightenment against the reactionary views of Schelling. Marx went beyond Epicurus while underlining his importance for a materialist analysis. He reined in some of his "exaggerations" and sharpened up his innate dialectics.

Baboon. 15.2.18

Rubric:

On recent attacks on the ICC on libcom

- 2814 reads

The publication of our article ‘Reflections on the split in the Anarchist Federation’[1] has been widely read (close to 1000 reads at the time of writing), but has also ignited a storm of virulent attacks on the ICC, led by two longstanding members of the libcom collective, Steven and Mike Harman[2].

The ostensible reason for these attacks was a short paragraph in the article describing the events at the Anarchist Bookfair which had precipitated the split in the AF, a clash between a group of radical feminists (labelled “Trans Exclusionary Radical Feminists” by their opponents) and supporters of “transgender rights” over the question of transphobia – hatred or discrimination against transgender people. This had not been the main focus of the article – the paragraph had figured as an introduction to a more general critical analysis of the statement of the group which had left the AF. But it was the central focus of the attacks on our article. We - or “the authors of the article” – were accused either of gross ignorance of the issues (and were given sundry links to sites where the basic terminology would be made clear to us) or of outright transphobia. The main evidence provided was that at the beginning of the article we had placed the word transphobia in inverted commas, as though it was not a real thing; but more importantly, that we had referred to transgender women (ie those who have “transitioned” from a male gender identity to a female one) as transgender males. According to our critics, we were thus providing support for the radical feminists, who had distributed leaflets at the Bookfair criticising proposed government legislation which will make gender identity a matter of subjective choice, because in the view of these particular feminists it will expose women-only spaces to the presence of people who they don’t consider to be women at all.

It’s true that this misuse of the current terminology was an error on our part, and we have made certain changes in the paragraph to make it clear that we are simply describing the position of the “TERFs” and in no way supporting them. But it was clear from the approach of posts attacking us that however much we altered the formulation used, we would still be judged guilty of promoting transphobia, because we have an entirely different approach to the whole issue. This is how Mike Harman deals with it. He cites the attempt by our poster on the thread, Alf, to focus on the real questions raised by the article: “is it true that significant parts of the anarchist movement are being pulled into the politics of 'identity', whether based on gender, sexuality, race or nationality?” and replies:

“You're asking the wrong question, because you don't understand the basis of the conflict. Another question to ask would be, ‘Why did two Green party members feel sufficiently emboldened that they could distribute transphobic leaflets at the anarchist bookfair, and put up posters in the toilets?’”

Harman’s post thus provides a justification for refusing to engage with the growing impact of identity politics on the anarchist milieu. Not only that, but Steven in particular repeatedly demanded that our entire article should be taken down – a clear attempt to silence us[3].

But in insisting that the one and only issue is the action of the “TERFs”, Harman also implies that unless you side with the anti-TERF resistance, you are providing ammunition for their transphobic agenda. In other words, what the posts by the libcom collective members really show is not our insidious prejudice against trans people, but the libcom collective’s own deepening involvement in identity politics or “id pol”. Small wonder that Steven (who is a remaining member of the AF) dismisses our view of the split as being an attempt – albeit partial and inadequate – to reject the growing weight of id pol, as “bollocks”.

For our part, we want to emphasise that not only do we not take sides in this clash between different brands of identity politics: we are opposed to all of them. As our sympathiser Baboon put it in a post on our forum: “I don't think that the fight between radical feminists and trans activists has any possible advantage for the proletariat or in any way assists the pressing needs of the class … I'd seen these two groups confronting each other on the TV weeks before the bookfair on Channel 4 news where (at a Gay Pride march I think) their confrontation was turning very ugly and very nasty[4]. At the bookfair apparently the police were called by one faction and both factions were involved in mobbing and scapegoating, a situation that showed nothing positive from a working class perspective and was entirely in line with certain populist developments arising from capitalism's decomposition”[5]

At the same time, both groups are founded on deep illusions in capitalist legislation. Some feminists seem to think that women are defended by current legislation, but will be undermined by the change. Meanwhile, some trans activists seem to think that the change to the Gender Recognition Act will be a great step forward for trans people. Both milieus have profound reformist illusions. And their goals are mutually exclusive, therefore deeply divisive.

WR, February 2018

[3] Echoed, more crudely, by the poster El Psy Congroo who simply told our comrade to “shut the fuck up”

[4] The incident in question actually took place at Speakers’ Corner in September 2017: https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2017/oct/26/woman-punched-in-brawl-b... [8]

Rubric:

Reflections on the split in the Anarchist Federation

- 3534 reads

The Anarchist Federation, one of the main anarchist organisations in Britain, has just been through a major split. Members in Leicester and London, including a number of founder members, have left the organisation following the tumult over the issue of “transphobia”[1] at October’s Anarchist Bookfair.

If we were right in our assessment of the AF as an internationalist anarchist group[2], this is a significant event which attests to growing difficulties across the entire spectrum of groups who are seeking to develop an authentic revolutionary opposition to capitalism – not only among anarchists but also within the communist left. We think that it is essential to understand the roots of these difficulties if we are to face up to the challenge they pose, and it is in this spirit that we aim to critically analyse the statement issued by those who have decided to leave the AF.[3]

The attempt to break with “identity politics”

The statement of the seceders begins thus:

“It has been over a month since the London Anarchist Bookfair and as a movement we are still reeling, with deep divisions between people who had respect for each other and once worked well together. We are still shocked, horrified and saddened by events as are most people, no matter what perspective or interpretation they have on what happened and the role of the Bookfair collective.

We were, until recently, members of the AF who did not sign the initial statement that was issued by Edinburgh AF and signed by two other AF groups, nor did we support the statement issued by other campaigns and organisations. We did not want to respond immediately as there are so many issues involved and emotions are strong. We hoped that after some time we could give a political assessment of the situation rather than just a knee-jerk reaction based on our emotional response to events and statements from other groups”[4].

The former members have reconstituted themselves into London Anarchist Communists and Leicester Anarchist Communists[5].

It’s not possible here to deal in any detail with the events at the Bookfair, which caused such ructions across the anarchist milieu and even reached the national press[6]. In essence it involved a clash between a group of feminists who intervened at the Bookfair with a leaflet arguing that new government legislation on “transgender rights” is an infringement on women’s rights to organize separately, since it would allow people who they – the leafleters – don’t consider to be women at all into spaces reserved by or for women. The leaflet provoked a lot of anger from “trans rights” supporters, who saw it as an attempt to whip up fear of transgender people by a tendency they call “Trans Exclusionary Radical Feminists” or TERFS, and one of the women supporting the leafleters, a well-known activist who was involved in the MacLibel case and has been targeted in a particularly vicious way by the undercover police, was subject to mobbing and accused of being a fascist. The Bookfair Collective, which attempted to intervene in the situation to calm it down, subsequently issued a statement saying that this would be its last Bookfair – it has experienced similar clashes in a number of other Bookfairs and its patience has run out[7].

These events are not unconnected to other scandals centred on the question of morality and behavior which have rocked the anarchist movement in the last few years, the most notable of which are “Aufhebengate” and the “Schmidt affair”[8], both of which raise the problem of the role played in the anarchist milieu by individuals with a dubious relationship with the police (in the first case) and with out-and-out racists in the second. We have also seen a substantial part of this milieu plunging into support for “national liberation” in the shape of the “Rojava revolution”, armed enclaves in Syria controlled by the Kurdish nationalists of the PKK and based on a semi-anarchist ideology of “democratic confederalism”[9], and an extremely widespread support for anti-fascism which was highlighted by the incidents around Charlottesville in the USA[10].

These developments are not taking place in a vacuum. The tendency, within anarchism, to abandon class politics and look for solutions in various forms of identity politics – whether based on gender, race, or nation – while not new, are certainly being exacerbated by the characteristics of the current historic period, in which capitalism is sinking towards barbarism while the working class, weakened by all the divisions engendered by this decomposing society, has found it extremely difficult to resist as a class and above all to rediscover its own perspective for the future of humanity. In a situation where the working class is tending to lose its sense of itself as a distinct social force, it is not surprising that the problem of class identity is being obscured by a fixation on other, more specific identities – a fixation which, while linked to genuine oppressions, tend to obscure the central problem of exploitation and the capitalist social relation.

The statement issued by the seceding groups is highly critical of the mobbing witnessed at the Bookfair. And while it affirms the importance of fighting against all particular forms of oppression, including transphobia, it also contains a questioning of the identity-based politics which it feels has become increasingly dominant within the AF, and a strong desire to return to “class struggle anarchism”. The question of internationalism is also directly posed by this split, because, although the AF published a fairly clear statement on the “Rojava revolution” some time ago[11], some of the comrades who left the organisation also consider that pro-PKK positions have also been increasingly influential within the organization[12].

These aspects of the statement are expressions of a proletarian reaction to the engulfing of the AF in the mire of identity politics and a drift towards support for radical forms of nationalism. They confirm what we wrote in our two-part article on internationalist anarchism in the UK, where we argued that for all its concessions to leftist campaigns, the AF was in the tradition of internationalist anarchism – of those currents in the anarchist movement which have stood against any participation in imperialist war[13]. The revival of the term “anarchist communism” (the AF had originally been called the Anarchist Communist Federation) is symbolic of this will to recover the healthiest parts of its tradition, which they feel can no longer be done within the AF.

And yet: the very fact that these criticisms of identity politics are carried out in the historic framework of anarchism means that they don’t – and cannot – go far enough.

Anarchist obstacles to theoretical advance

What is the evidence for this claim?

· The statement begins by admitting how difficult it has proved to overcome all the divisions within the working class and to build a revolutionary movement committed to the overthrow of capitalism. But it gives little sign of trying to situate these difficulties in the overall context of the present period – a period, as we have noted, marked by a loss of class identity and a low level of class struggle. It’s true that prior to the split the Leicester group of the AF had held a meeting in Leicester and one at the Anarchist Bookfair, as well as writing an article that started a thread on libcom, under the heading ‘Is the working class movement dead?’[14], which posed serious questions about the problems facing the working class and revolutionaries. There is a recognition in the article that the class struggle has been weakening over a long period but the approach to the problem in the presentation to the meetings is essentially an empirical one which is unable to place it in the global, historic context of capitalism’s terminal phase of decline.

· Although it affirms the central role of the class struggle, the statement does not pose the fundamental theoretical issue: the nature of the working class as a historic, revolutionary class, or as Marx famously put it in 1843: “a class with radical chains, a class of civil society which is not a class of civil society, an estate which is the dissolution of all estates, a sphere which has a universal character by its universal suffering and claims no particular right because no particular wrong, but wrong generally, is perpetuated against it; which can invoke no historical, but only human, title; which does not stand in any one-sided antithesis to the consequences but in all-round antithesis to the premises of German statehood; a sphere, finally, which cannot emancipate itself without emancipating itself from all other spheres of society and thereby emancipating all other spheres of society, which, in a word, is the complete loss of man and hence can win itself only through the complete re-winning of man. This dissolution of society as a particular estate is the proletariat”. (Critique of Hegel’s Philosophy of Right)

It is this conception which enables us to understand why the struggle of the proletariat contains, in potential, the solution to all the particular oppressions spawned by capitalist society. But this conception of the proletariat is, of course, the one developed by Marx and the marxist movement, which affirms that the class struggle is not restricted to the economic sphere but has numerous dimensions: social, political, moral, intellectual. It was this understanding which enabled Lenin, that bugbear of the anarchists, to develop a critique of the Economist vision which limits the class movement to something that takes place in the factories and essentially on a day to day basis. And in many ways this is precisely the conception of the main currents in anarchism – most notable the anarcho-syndicalists, but also of those who produced the statement, for whom a class struggle orientation seems to boil down to “getting involved” in the workplace and the local community, which is presented almost as a panacea: “our answer to the first issue” – the reluctance of working people to get involved in revolutionary politics – “is that we need to make sure as anarchists we are directly involved in struggle, in the workplace and the community”. The issue for us here is not whether revolutionaries should engage with struggles in the workplace or the neighbourhood, but the content of that engagement – its methods and objectives, which are nowhere posed in the seceding statement. Otherwise comrades risk burning themselves out in non-stop activism whose real content is essentially a trade unionist one. This is evident in the case of the anarcho-syndicalists whose “organising” role is linked to a project of building a “revolutionary union”. But even those who appear to be more critical of trade unionism can be led back to union-building through a simple focus on day-to-day workplace organising. It was pointed out on the libcom thread about the AF split that some of those who left the AF had previously joined the IWW, which is not entirely consistent with the AF’s position on anarcho-syndicalism, while some of the campaigns of the more “autonomist” Angry Workers of the World group in West London seem to be heading towards calls to build new IWW or “independent union” branches[15].

· This restricted view of the class struggle does not offer any real alternative to the ideas of “idpol”, for whom being working class is another particular oppression, another separate identity with its own rights to defend. The statement’s critique of identity politics and the kind of mobbing witnessed at the Bookfair makes some valid points – in particular by recognising that fighting against oppressive and divisive ideologies is one that takes place inside the working class, and that those proletarians who are weighed down by various kinds of prejudices need to be won over in the course of the class struggle, not treated as enemies. And yet the ABC of identity politics is not questioned: “We support oppressed groups to organise autonomously”, without any discussion about whether such forms of organising – by gender, sexual orientation, race – tend to become inter-classist by definition and create obstacles to a wider class unity. The statement mentions that it disagrees with the statements put out by Edinburgh and two other AF groups, but it doesn’t mention the fact that one of these groups was the “Trans Action Faction” within the AF[16], and no criticism is made of the organisational model adopted by the AF, which presents itself as a myriad not only of local groups but of groups organised around sexual and other identities. Again on the organisational question, while it’s recognised in the statement that a lot of people entered the AF without really agreeing with its Aims and Principles, the new group goes no further than reprinting the original document and doesn’t appear to have an answer to the pertinent question posed by Darren P on the libcom thread: “Just out of interest how was it that people whose politics are closer to liberal idpol than anarchist-communism came to be the majority in the AF anyhow? Isn’t there any kind of screening process for new members? In other words, is there not a need to examine the ‘entry requirements’ of a genuine revolutionary organisation?”[17]

Does any of this mean that all the problems posed by the different forms of oppression and division reinforced by capitalist society have been solved by the marxist movement? Not at all: even when we are talking about authentic marxism and not its Stalinist or leftist caricature, its various currents have not been immune from workerist ideologies, reductionist visions of class, and even overtly “patriarchal attitudes”. But we are convinced that it’s only the marxist, historical method that will enable us to understand the origins of different forms of oppression and the way to oppose and overcome them, which can only mean starting from a lucid class standpoint that states openly that identity politics are a dead-end[18].

For us, the underlying problem is that, historically speaking, anarchism itself stems from deep confusions about class: the Proudhonist tendency classically expressed a reaction by the artisan to being dissolved into the proletariat; the Bakuninist current tried to respond to the development of the proletariat with a more collectivist approach but without jettisoning the attachment to the centrality of “liberty” versus “authority; the anarcho-syndicalists, while being a healthy response to the parliamentary cretinism overcoming social democracy at the beginning of the 20th century, fell into the workerist view of the class struggle we mentioned above, evading or even rejecting the political dimension of the class movement. This means that simply returning to these historic roots will not provide the basis for a real clarification and a genuine advance.

There is also an inherent tendency within anarchism towards what many anarchists themselves describe as “the Big Tent” – a kind of family conception in which almost everyone who pins the “anarcho-“ or “libertarian” label on their jacket is welcome through the door. This is typified by the Anarchist Bookfair which has always had the vaguest and most inconsistent criteria for participation, but in a narrower sense the same criticism can be made of the AF, which reveals itself to be a marsh inhabited by different and often antagonistic species.

Anarchists have often taken offense at our use of terms the marsh or the swamp to describe the milieu they inhabit, but we see it as a necessary characterisation of a real political terrain in this society – the middle-ground between the two major classes, the proletariat and the bourgeoisie, made up not only of direct expressions of the intermediate layers (urban petty bourgeoisie, peasantry etc) but also, on the one hand, of degenerating proletarian currents heading towards the ground of bourgeois, leftist politics, and on the other hand, of groups and individuals that are seeking seriously to reach the proletarian shore. A place of transition, but not a place to get bogged down.

In our series on the communist left and internationalist anarchism, we insisted on the need for fraternal discussion between our tendency and those anarchists who indeed express a proletarian vision even if, to our mind, they have not yet left the old swamp behind entirely. Regarding the split in the AF, for all our criticisms, we remain open to further debate, not only with those who left but also with those who chose to stay in the AF. For us, political criticism is not in contradiction with fraternal discussion, and should not be confused with sectarianism[19].

Amos 23.2.18

1. This is the current “normal” term for discrimination, hatred or prejudice against people who opt for a different gender identity than the one given when they are born. However, even among those activists involved in the issue, it is not immune from criticism: "we’ve been intentionally moving away from using words like ‘transphobic’, ‘homophobic,’ and ‘biphobic’ because (1) they inaccurately describe systems of oppression as irrational fears, and (2) for some people, phobias are a very distressing part of their lived experience and co-opting this language is disrespectful to their experiences and perpetuates ableism." https://lgbtqia.ucdavis.edu/educated/glossary.html [10]

2. https://en.internationalism.org/series/1292 [11]

https://en.internationalism.org/wr/344/brit-anarchy [12]

https://en.internationalism.org/wr/345/brit-anarchy [13]

3. Certain changes have been in this article since it was first published on 5.2.18. The reasons for these changes are explained in our accompanying article 'On recent attacks on the ICC on Libcom' https://en.internationalism.org/icconline/201802/14928/recent-attacks-icc-libcom [14]

4. https://communistanarchism.blogspot.co.uk/2018/01/class-struggle-anarchist-statement-on_1.html [15]

5. [email protected] [16]; https://leicesteraf.blogspot.co.uk/ [17]

6. https://www.theguardian.com/society/2017/nov/26/transgender-anarchist-book-fair-transphobia-row [18]

7. Statements by the Bookfair Collective can be found at anarchistbookfair.org.uk [19].

8. See our statement on “Aufhenebgate”: https://en.internationalism.org/icconline/201305/7746/aufhebengate [20] on the “Schmidt affair”: https://libcom.org/discussion/ak-press-allegations-against-michael-schmidt [21]

9. https://en.internationalism.org/icconline/201412/11625/anarchism-and-imperialist-war-nationalism-or-internationalism [22]

10. en.internationalism.org/icconline/201709/14390/anti-fascism-still-formula-confusion [23].

We should also mention that there has also been a split in the main international organization of the anarcho-syndicalists, the International Workers’ Association, which appears to centre round its most numerous section, the CNT in Spain. See for example https://libcom.org/article/cnt-and-iwa-part-2-crisis-iwa-seen-cnt [24].

11. https://libcom.org/article/anarchist-federation-statement-rojava-december-2014 [25]

12. See https://libcom.org/forums/anarchist-federation/whats-going-afed-27122017 [26], especially p 2 and 3

13. See note 2 for references

14. https://libcom.org/article/working-class-movement-dead [27]

15. Post 184, Steven [28]. On the AWW’s drift towards syndicalism: “Workplace groups: Currently we work in a major warehouse of a supermarket chain and factories of a major ready-meal producer and try to establish workers groups. Together with the IWW we try to organise independent union structures in ten local companies”. https://libcom.org/article/migration-and-national-social-democracy-britain [29]

16. afed.org.uk/afed-trans-action-faction-statement-in-response-to-events-at-london-anarchist-bookfair-2017 [30]

17. Post 19, Darren P [31].

18. This is why we are also publishing the article ’The dead-end of racial identity politics’ by the US group Workers’ Offensive in this issue (www.workersoffensive.org/single-post/2017/10/13/The-Dead-End-of-Racial-I... [32])

19. In this regard we note that the new group carries on a practice established for some years now by the Anarchist Bookfair (not to mention numerous other radical websites), in that it publishes a link to the Communist Workers’ Organisation, a left communist organisation whose positions are close to ours, but not to the ICC – just the Bookfair allowed the CWO to hold a stall and meetings while requests from the ICC to do the same were rejected year after year. This attitude is incoherent and a real expression of sectarianism. If anyone in the anarchist world considers that the ICC deserves to be treated like a pariah, let them argue the case, and we will respond with our own arguments.

Rubric:

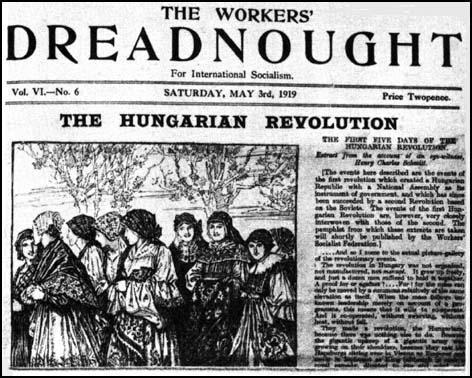

Suffragism or communism?

- 1620 reads

Faced with the torrent of “celebration” about how women (or some women) were given the vote in 1918, we are pleased to publish this short response by a comrade who has moved close to the views of left communism – and thus to the ideas of Sylvia Pankurst in 1918, who exposed the granting of the vote as a deception aimed at stemming the tide of revolution that had been provoked by the horrors of the First World War[1]. ICC

The Workers’ Socialist Federation began life as the East London Federation of the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU), the primary organisation for women’s suffrage led by Emmeline and Christabel Pankhurst. In contrast to the WSPU, the East London Federation was disproportionately composed of working-class (as opposed to middle-class) women, and open to men. Sylvia Pankhurst was therefore concerned with social reforms and industrial action for the improvement of the dire conditions of the working-class, whilst the WSPU privileged [propertied] women’s suffrage above any other cause and aimed to appeal to middle-class women. The working-class and reformist nature of the East London Federation led to its expulsion from the WSPU in 1914.

During the First World War, most of the international, women's suffrage movement – e.g. the WSPU in Britain, or National American Woman Suffrage Association in the US – rallied to the support of their countries’ war efforts, engaging in patriotic/nationalist, pro-war sloganeering. The war exacerbated the poverty and hardships of the working-class in East London, and Sylvia Pankhurst tried in vain to alleviate the suffering of workers through charity, lobbying for reforms and co-operatives.

The Russian revolution led to a radical alteration in Sylvia Pankhurst’s politics. When Pankhurst changed the name of her organisation from the “East London Federation of Suffragettes”, to the “Women’s Suffrage Federation”, to “Workers' Suffrage Federation”, and finally the "Workers' Socialist Federation", and the name of her paper from Women’s Dreadnought to Workers' Dreadnought, it illustrated this shift in her politics, away from ‘women’ (an interclassist category), towards working-class women, finally to the working class in general, and her ultimate rejection of the politics of reformist suffragism in favour of communism.

By 1918/9, Pankhurst recognised that it was pointless, and in fact reactionary, to campaign for suffrage amidst a world, proletarian revolutionary wave. At a time when the very existence of parliaments and nation-states was put into question by the revolutionary working-class, whether or not the working-class, or women, or middle-class women, should have the right to vote in elections to capitalist parliaments had simply lost all relevance. Parliaments were no longer a site of meaningful, political contestation for the proletariat, the future was to be found in the form of territorial soviets (workers' councils).

“The Communist Party, believing that instruments of capitalist organization and domination cannot be used for revolutionary ends, refrains from participation in Parliament and in the Bourgeois Local Government system. It will ceaselessly impress upon the workers that their salvation lies not in the organ of the bourgeois “democracy,” but through the Workers’ Soviets.

The Communist Party refuses all compromise with Right and Centrist Socialism. The British Labour Party is dominated by Opportunist Reformists, Social Patriots, and Trade Union Bureaucrats, who have already allied themselves with capitalism against the workers’ revolution at home and abroad. The construction and constitution of the British Labour Party is such that the working masses cannot express themselves through it. It is affiliated and will remain affiliated to the Second International, so long as that so-called International shall exist.” (The Communist Party: Provisional Resolutions towards a Programme, 1920)

This great public campaign around celebrating suffragism, and the attempt to portray Sylvia Pankhurst as a suffragette, rather than the anti-parliamentary communist she became, is part of a ruling-class ideological offensive: to recuperate what can be recuperated, to cover-up what can't be recuperated, to rewrite history, leaving-out all the revolutionary bits. In general, undermining the historical memory of the workers' movement in the centenary years of the worldwide, revolutionary wave of 1917-23.

Why is the ruling-class so loud in its celebration of the Representation of the People Act 1918, as some great moment in British history? Why does the ruling class portray suffragettes as national heroes? What would the left communist Sylvia Pankhurst have thought about this national celebration of suffragism?