International Review no.66 - 3rd quarter 1991

- 3663 reads

How the revolutionary wave of 1917-23 was weakened by support for "national liberation" movements

- 5198 reads

The Kurdish tragedy is the latest demonstration of the bloody barbarity brought about by so-called 'national liberation' struggles.

The United States, Great Britain, Turkey, Iran, all the different imperialist protagonists who brought about the outrage of the Gulf War, encouraged the Kurds in one way or the other to rise up in armed insurrection for their 'national liberation'. Now we can see how they left Saddam Hussein to crush them and cast them into exile.

They are all accomplices to this genocidal slaughter and they have all used 'national liberation' as a fig leaf for their imperialist ambitions. In this pack of dogs we have to include the Kurdish leaders who have made an agreement with the Butcher of Baghdad to reduce 'national independence' to the 'first step' of 'autonomy', a 'first step' that also took place in 1970, 1975, and 1981...!

Capitalism has entered its final phase: decomposition. A phase in which wars like that in the Gulf and ethnic-nationalist massacres like those in Yugoslavia and the USSR, or the killings between the Arabs and Kurds in Iraq, will increasingly proliferate. Both take place under the same banner of 'national liberation' which, in many cases, is the cynical disguise for the imperialist ambitions of different states, especially the great powers; in the other cases it is just an irrational drunkenness which carries away the brutalised and desperate masses. In both it is an expression of the mortal bankruptcy of the capitalist order, of the threat it represents to the survival of humanity.

Against all of this, only the proletariat can offer a perspective of reorganising society around social relations based on the real unification of humanity, on production dedicated to the full satisfaction of human needs; in sum, a world community of free and equal human beings who work with and for each other.

In order to orient its struggles around this perspective the proletariat must clearly reject the whole ideology of 'national liberation', which serves only to tie it to the old society [1] [1]. In the first part of this article we are going to analyse how, in the revolutionary experience of 1917-23, this mystification represented a crucial factor in the failure of the revolution and provided the capitalist states with a means of salvation that resulted in a tragic procession of war and barbarity, the price mankind has paid for the survival of the capitalist regime over the last 70 years.

The Second Congress of the Communist International (March 1920) adopted the 'Theses on the national and colonial question' whose basic idea was: "All events in world politics are necessarily concentrated on one central point, the struggle of the world bourgeoisie against the Russian Soviet Republic, which is rallying around itself both the soviet movements among the advanced workers in all countries, and all the national liberation movements in the colonies and amongst the oppressed peoples, convinced by bitter experience that there is no salvation for them except in union with the revolutionary proletariat and in the victory of Soviet power over world imperialism" (Documents of the Communist International, ed J Degras, page 138).

This hope was quickly refuted by events from the beginning of the Russian Revolution. The policy of support for 'national liberation' struggles practiced by the CI and the proletarian bastion in Russia created a barrier against the international extension of the proletarian revolution and fundamentally weakened the consciousness and unity of the international proletariat, contributing to the failure of its revolutionary efforts.

A noose around the neck of the Russian Revolution

The October revolution was the first step in the revolutionary movement of the proletariat on a world scale: "That the Bolsheviks have based their policy entirely upon the world proletarian revolution is the clearest proof of their political farsightedness and firmness of principle and of the bold scope of their politics" (Rosa Luxemburg, 'The Russian Revolution' in Rosa Luxemburg Speaks, Pathfinder Press, page 368)

In accordance with this thinking, where the essential issue was the international extension of the revolution, support for national liberation movements in the countries oppressed by the great metropolitan imperialists was seen as a tactic for winning additional support for the world revolution.

From October 1917, the Bolsheviks pushed for the independence of the countries which the Czarist empire had kept subjugated: the Baltic countries, Finland, Poland, the Ukraine, Armenia etc... They believed that such an attitude would guarantee the revolutionary proletariat indispensable support for its efforts to retain power while waiting for the maturation and explosion of the proletarian revolution in the great European countries, especially Germany. These hope were never to be fulfilled:

· Finland: the Soviet government recognised its independence on the 18th of December 1917. The working class movement in this country was very strong: it was on the revolutionary ascent, it had strong links with the Russian workers and had actively participated in the 1905 and 1917 revolutions. It was not a question of a country dominated by feudalism, but a very developed capitalist territory. And the Finnish bourgeoisie used the Soviet power's gift in order to crush the workers' insurrection that broke out in January 1918. This struggle lasted nearly 3 months but, despite the resolute support the Soviets gave to the Finnish workers, the new state was able to destroy the revolutionary movement, thanks to German troops whom they called on to help them;

· The Ukraine: the local nationalist movement did not represent a real bourgeois movement, but rather obliquely expressed the vague resentments of the peasants against the Russian landlords and above all the Poles. The proletariat in this region came from all over Russia and was very developed. In these conditions the band of nationalist adventurers that set up the 'Ukraine Rada' (Vinnickenko, Petlyura etc.) rapidly sought the patronage of German and Austrian imperialism. At the same time it dedicated all its forces to attacking the workers' soviets, which had been formed in Kharkov and other cities. The French general Tabouis who, because of the collapse of the central powers, replaced the German influence, employed Ukrainian reactionary bands in the war of the White Guards against the Soviets.

"Ukrainian nationalism... was a mere whim, a folly of a few dozen petty bourgeois intellectuals without the slightest roots in the economic, political or psychological relationships of the country; it was without any historical tradition, since the Ukraine never formed a nation or government, was without any national culture... To what was at first a mere farce they lent such importance that the farce became a matter of the most deadly seriousness - not as a serious national movement for which, afterwards as before, there are no roots at all, but as a shingle and rallying flag of counter-revolution. At Brest, out of this addled egg crept the German bayonets" (Rosa Luxemburg, idem, pages 382-2);

· The Baltic states (Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania): the workers' soviets took power in this zone at the same moment as the October revolution. 'National liberation' was carried out by British marines: "With the termination of hostilities against Germany, British naval units appeared in the Baltic. The Estonian Soviet Republic collapsed in January 1919. The Latvian Soviet Republic held out in Riga for five months and then succumbed to the threat of British naval guns" (E.H.Carr, The Bolshevik Revolution, vol. 1, page 317)

· In Asiatic Russia, Armenia, Georgia and Azerbaijan: "A Bashkir government under one Validov, which had proclaimed an autonomous Bashkir state after the October revolution, went over to the Orenburg Cossacks who were in open warfare against the Soviet Government; and this was typical of the prevailing attitude of the nationalists" (idem, page 324). For its part the 'national-revolutionary' government of Kokanda (in central Asia), with a programme that included the imposition of Islamic law, the defence of private property, and the forced seclusion of women, unleashed a fierce war against the workers' Soviet of Tashkent (the principal industrial city of Russian Turkestan).

· In Caucasia a Transcaucasian republic was formed, and its tutelage was fought over between Turkey, Germany and Great Britain. This caused it to break up into 3 'independent' republics (Georgia, Armenia and Azerbaijan), which fiercely confronted each other, urged on in turn by each of the contesting powers. The three republics supported with all their forces the British troops in their battle against the Baku workers' Soviet, which from 1917-20 suffered bombardment and massacres by the British;

· Turkey: from the beginning the Soviet government supported the 'revolutionary nationalist' Kemal Attaturk. Radek, a member of the CI, exhorted the recently formed Turkish Communist Party thus: "Your first task, as soon as you have formed as an independent party, will be to support the movement for the national freedom of Turkey" (Acts of the first four Congresses of the CI). The result was a catastrophe: Kemal crushed without leniency the strikes and demonstrations of the young Turkish proletariat and, if for a time he allied with the Soviet government, it was only done to put pressure on the British troops who were occupying Constantinople, and on the Greeks who had occupied large parts of Western Turkey. However, once the Greeks had been defeated and having offered British imperialism his fidelity if they left Constantinople, Kemal broke off the alliance with the Soviets and offered the British the head of the Turkish Communist Party, which was viciously persecuted.

· The case of Poland should also be mentioned. The national emancipation of Poland was almost a dogma in the Second International. When Rosa Luxemburg, at the end of the 19th century, demonstrated that this slogan was now erroneous and dangerous since capitalist development had tightly bound the Polish bourgeoisie to the Russian Czarist imperial caste, she provoked a stormy polemic inside the International. But the truth was that the workers of Warsaw, Lodz and elsewhere were at the vanguard of the 1905 revolution and had produced revolutionaries as outstanding as Rosa. Lenin had recognised that "The experience of the 1905 revolution demonstrated that even in these two nations (he is referring to Poland and Finland) the leading classes, the landlords and the bourgeoisie, renounced the revolutionary struggle for liberty and had looked for a rapprochement with the leading classes in Russia and with the Czarist monarchy out of fear of the revolutionary proletariat of Finland and Poland" (minutes of the Prague party conference, 1912).

Unfortunately the Bolsheviks held onto the dogma of 'the right of nations to self-determination', and from October 1917 on they promoted the independence of Poland. On 29 August 1918 the Council of Peoples Commissars declared "All treaties and acts concluded by the government of the former Russian Empire with the government of Prussia or of the Austro-Hungarian Empire concerning Poland, in view of their incompatibility with the principle of the self-determination of nations and with the revolutionary sense of right of the Russian people, which recognises the indefeasible right of the Polish people to independence and unity, are hereby irrevocably rescinded" (quoted in E.H. Carr, The Bolshevik Revolution, vol 1, p 293).

While it was correct that the proletarian bastion should denounce and annul the secret treaties of the bourgeois government, it was a serious error to do so in the name of 'principles' which were not on a proletarian terrain, but a bourgeois one, viz the 'right of nations'. This was rapidly demonstrated in practice. Poland fell under the iron dictatorship of Pilsudski, the veteran social patriot, who smashed the workers' strikes, allied Poland with France and Britain, and actively supported the counter-revolution of the White Armies by invading the Ukraine in 1920.

When in response to this aggression the troops of the Red Army entered Polish territory and advanced on Warsaw in the hope that the workers would rise up against the bourgeoisie, a new catastrophe befell the cause of the world revolution: the workers of Warsaw, the same workers who had made the 1905 revolution, fell in behind the 'Polish Nation' and participated in the defence of the city against the soviet troops. This was the tragic consequence of years of propaganda about the 'national liberation' of Poland by the Second International and then by the proletarian bastion in Russia. [2] [2]

The outcome of this policy was catastrophic: the local proletariats were defeated, the new nations were not 'grateful' for the Bolsheviks' present and quickly passed into the orbit of British imperialism, collaborating in their blockade of the Soviet power and sustaining with all the means at their disposal the White counter-revolution which provoked a bloody civil war.

"The Bolsheviks were to be taught to their own great hurt and that of the revolution, that under the rule of capitalism there is no self-determination of peoples, that in a class society each class of the nation strives to 'determine itself' in a different fashion, and that, for the bourgeois classes, the stand-point of national freedom is fully subordinated to that of class rule. The Finnish bourgeoisie, like the Ukrainian bourgeoisie, were unanimous in preferring the violent rule of Germany to national freedom, if the latter should be bound up with Bolshevism." (Rosa Luxemburg, 'The Russian Revolution', Rosa Luxemburg Speaks, page 380)

National liberation will not cure national oppression

The Bolsheviks thought that "in order to affirm the workers' international unity it was first necessary to uproot all vestiges of the past inequality and discrimination between nations". Hadn't these vestiges subjected the workers of these countries to the reactionary nationalism of the Czarist empire? Didn't this create an obstacle to their unity with the Russian workers, who could be seen as accomplices to Great Russian chauvinism? Wouldn't the young proletariat of the colonial and semi-colonial countries have a hostile attitude towards the proletariat of the great metropoles as long as their countries had not become independent nations?

It is certain that capitalism did not create and organise the world market in a conscious way. It developed in a violent, anarchic manner, through antagonisms between nations. Everywhere it sowed all kinds of discrimination and oppression, particularly national, ethnic, and linguistic ones. These weighed heavily on the workers of different countries, complicating the process towards the unification and self-awareness of the class.

However, it was erroneous and dangerous to seek to solve this by encouraging the formation of new nations which - given the saturation of the world market - could have no economic viability, and would only reproduce these wounds on a much vaster scale. The experience of the peripheral peoples of the Czarist empire was conclusive. The Polish nationalists used their 'independence' to persecute the Jewish, Lithuanian and German minorities; in Caucasia, the Georgians persecuted the Armenians and the Azeris, the Armenians the Turkamens and the Azeris, while later on the latter did the same to the Armenians...; the Ukrainian Rada declared its hatred of the Russians, Poles and Jews... and these events were an omen of the terrible nightmare which has unfolded throughout capitalism's decadence: simply remember the Hindus' bloody orgy against the Muslims in 1947, that of the Croats against the Serbs during the Nazi occupation and the revenge of the latter against the former once Yugoslavia was 'liberated' by Tito. And now today we have the bloody witches' Sabbath of nationalist pogroms in Eastern Europe and Asiatic Russia. We have to be clear: 'national liberation' will not stop national oppression, but instead will reproduce it even more irrationally. It is like using petrol to put a fire out.

It is only in the proletariat, in its revolutionary being and in its struggle, that we can find the bases for combating and overcoming all the varieties of national, ethnic and linguistic discrimination engendered by capitalism: "big industry created a class, which in all nations has the same interest and with which nationality is already dead; a class which is really rid of all the old world and at the same time stands pitted against it." (Marx and Engels, The German Ideology)

National liberation pushes the non-exploiting strata into the arms of capital

The Bolsheviks, who always based their policies on the idea of reinforcing the world revolution, thought that they could win over the non-exploiting strata of these nations - peasants, certain middle classes etc - through supporting 'national liberation' and other classical demands of the programme of the bourgeois revolutions (agrarian reform, political freedoms, etc).

These strata occupy an unstable position in bourgeois society; they're heterogeneous, without any future as such. Although oppressed by capitalism they lack any clear or defined interests of their own, and this ties them to the conservation of capitalism. The proletariat cannot win them over by offering them a platform based on 'national liberation' and other demands situated on the bourgeois terrain. Such proposals push them into the arms of the bourgeoisie who can manipulate them with demagogic promises and so turn them against the proletariat.

Clearly the demands of the bourgeois programme, which are most sensitive to the peasants and petty-bourgeoisie (agrarian reform, linguistic freedom within the national terrain, etc), have never been completed by the bourgeoisie. But in the period of capitalism's decadence the new nations are incapable of completing these demands, which clearly constitute a reactionary utopia, impossible under a capitalism that cannot expand, but is increasingly rent by violent convulsions.

Does this mean that the proletariat must take up demands which historical evolution have thrown into the dustbin, in order to demonstrate that it is more 'consistent' than the bourgeoisie?

No way! This approach, which weighed so heavily on the Bolsheviks and other revolutionary fractions, was a poisonous residue secreted by the gradualist and reformist thinking which led social democracy to its ruin. It is a speculative and idealist vision of capitalism, which holds that it has to complete its programme 100%, and in all countries before humanity is ready for communism. This is a reactionary utopia which does not correspond to the reality of a system based on exploitation, a system whose aim is not to carry out a supposed social project but to extract surplus-value. If in the ascendant phase of capitalism the bourgeoisie usually forgot its 'programme' after it had achieved power, making frequent pacts with the remnants of the old feudal classes, once the world market was formed and capitalism entered into its historical decline, this 'programme' was converted into a vulgar mystification.

The proletariat will only open a crack in its revolutionary alternative if it attempts the realisation of 'the unfinished bourgeois programme', and the bourgeoisie will grab onto this as a means of salvation. The best way of winning over the non-exploiting strata to the proletarian cause, or at least neutralising them in the decisive confrontations with the bourgeois state, is for the working class to consistently and fully affirm its own programme. It is the perspective of the abolition of class privileges, the hope of a new organisation of society which will safeguard the survival of humanity; it is the clear and resolute affirmation of the proletariat as an autonomous class, as a social force that openly presents itself as a candidate to take power; it is the massive self-organisation of the class in workers' councils, that will permit the creation of a platform capable of winning over these vacillating and unstable classes.

"Because it cannot assign itself the task of establishing new privileges, the proletariat can only base its struggles on political positions which result from its particular class programme - the proletariat represents, within the diverse classes of capitalist society, the only one able to build the society of the future. It is only on this basis that it can pull the middle social strata into the struggle. These classes will only unite with the proletariat in particular historical circumstances, when the contradictions of capitalist society blossom fully and the proletariat begins to mount its revolutionary assault. Only then will they understand the necessity of combining with the proletariat" (Bilan no 5, 'Principles: weapons of the revolution').

'National liberation': a factor in the disintegration of proletarian consciousness

The proletarian revolution is not a predestined product of objective conditions in which any expedient tactic can serve to carry it out. Although it is a historical necessity and its objective conditions have been furnished by the formation of the world market and the proletariat, the communist revolution is essentially a conscious act.

On the other hand, the proletariat, unlike past revolutionary classes, does not posses any economic power in the old society: it is at the same time an exploited and a revolutionary class. What makes it decisive and unique in history are its weapons for the destruction of the old society: its unity and consciousness, weapons that in turn constitute the foundations for the new society.

Consciousness is vital for the advance of its struggle, in which "on each occasion, the problem that the proletariat has to confront is not one of obtaining the best advantage or the greatest number of allies, but of being coherent with the system of principles which define its class... classes must exist in an organic and political configuration without which, despite being determined by the evolution of the productive forces, it runs the risk of remaining bound for a long time by the old class which, in its turn - in order to resist - will shackle the course of economic evolution" (Bilan no 5, idem).

From this perspective the support for 'national liberation struggles' during the revolutionary period of 1917-23 had disastrous consequences for the world proletariat, for its vanguard - the Communist International - and for the first bastion to carry out its revolutionary task: Russia.

The historical period of decisive confrontations between Capital and Labour was opened up by the First World War. In this period there is no alternative between the international proletarian revolution and the submission of the proletariat to the national interests of each bourgeoisie. Support for 'national liberation', although conceived as a 'tactical' element, led to the disintegration, corruption and decomposition of proletarian consciousness.

We have already seen that the 'liberation' of the peripheral peoples of the Czarist empire did not bring any advantage to the Russian revolution, but rather contributed to the growth of a cordon sanitaire around it: a group of nations with proletariats who were combative and had an old tradition were firmly closed off from the penetration of revolutionary positions, and an insurmountable abyss was opened up between the Russian and German workers.

How is it possible that the workers of Poland, the Ukraine, Finland, Baku, Riga, who had been at the forefront of the 1905 and 1917 revolutions, who engendered communist militants of the clarity and integrity of Rosa Luxemburg, Piatakov, Jogisches etc., were so rapidly defeated and crushed in 1918-20 by their own bourgeoisies and became, in many cases vehemently, opposed to the Bolsheviks' slogans?

There can be no doubt of the decisive influence of the nationalist poison: "The mere fact that the question of national aspirations and tendencies towards separation were injected at all in the midst of the revolutionary struggle, and were even pushed into the foreground and made into the shibboleth of socialist and revolutionary policy as a result of the Brest peace, has served to bring the greatest confusion into socialist ranks and has actually destroyed the position of the proletariat in the border countries" (Rosa Luxemburg, 'The Russian Revolution', idem, page 381).

Just as it pushed the workers of these countries towards the illusory lure of 'independence' and the 'development of the country free from the Russian yoke', 'national liberation' increasingly created a rift between them and the Russian proletariat, with whom they had shared many struggles and at times had taken the first step in decisive combats.

The International, the world communist party, is a pivotal factor in the class consciousness of the proletariat. Its clarity and coherence are vital to the strength, unity and consciousness of the proletariat. Support for 'national liberation' played a decisive role in the opportunist degeneration of the Communist International.

The Communist International was constituted on a central principle: capitalism has entered its decadent epoch, and the task of the proletariat cannot be to reform or improve it but to destroy it: "A new epoch is born: The epoch of capitalism's decay, its internal disintegration; the epoch of the proletarian, communist revolution" (Platform of the Communist International, 1919). However, support for 'national liberation' movements opened a very dangerous crack in this clarity, an opening towards the penetration of opportunism. It introduced into a programme aimed at the destruction of the old order a task that belonged entirely to that same old order. The tactic of combining the revolutionary struggles in the metropoles with the 'national liberation' struggles in the colonies led to the conclusion that the hour for the destruction of capitalism had not arrived yet: it implied that the world was divided into two areas (one 'ripe' for the proletarian revolution and another where capitalism still had to develop) and that capitalist expansion was still on the cards (for marxists 'national liberation' could have no other meaning than this).

This germ of confusion was an open door to the opportunism that increasingly developed with the reflux of the revolutionary struggles of the proletariat in Europe.

The party is not a passive product of the class movement, but an active factor in its development. Its clarity and determination are crucial to the outcome of the proletarian revolution; equally, its confusions, ambiguities and incoherence powerfully contribute to the confusion and defeat of the class. The evolution of the CI in its posture on the national question bears witness to this.

The 1st Congress, which took place when the revolutionary wave was at its height, posed as a task the abolition of national frontiers: "The end result of the capitalist mode of production is chaos, which only the largest productive class, the working class, can overcome. This class must establish a real order, the communist order. It must break the domination of capital, make wars impossible, destroy all national borders, transform the whole world into a community that produces for itself, and makes brotherhood and liberation of peoples a reality" (Platform of the CI).

In the same way, it was a given that the small states could not break the yoke of imperialism and could not but submit to its game: "The goal of Entente policy in the vassal states and in the recently created republics (Czechoslovakia, Yugoslavia, and also Poland, Finland and so on) is to organise national counter-revolutionary movements based on the ruling classes and social nationalists. This movement is meant to target the defeated states, maintain a balance of power among the newly created states, subordinating them to the Entente, retard revolutionary movements within the new 'national' republics, and, lastly, furnish the White guards needed for the struggle against the international revolution and the Russian revolution in particular" ('Theses on the International Situation and the Policy of the Entente', First Congress of the CI). And, in short, it demonstrated that the national state had been condemned by history: having given a vigorous impulse to capitalist development, the nation state had become too narrow for the development of the productive forces.

Thus we can see how the First Congress of the CI laid the bases for overcoming the initial errors on the national question; but these points of clarity were not developed. Instead, because of the defeats of the proletariat and the inability of the CI majority to take them further forward, they were liquidated little by little by the dark shadow of opportunism. The Fourth Congress (1922), with its theses on the Eastern Question, marked an important step in this regression since "proletariat and peasants were required to subordinate their social programme to the immediate needs of a common national struggle against foreign imperialism. It was assumed that a nationally minded bourgeoisie, or even a nationally minded feudal aristocracy, would be ready to conduct a struggle for national liberation from the yoke of foreign imperialism in alliance with the revolutionary proletarians and peasants, who were only waiting for the moment of victory to turn against them and overthrow them" (E.H. Carr, The Bolshevik Revolution, vol. 3, pages 477-8).

With later events, the proclamation of 'socialism in one country', the definitive defeat of the proletarian bastion in Russia and its integration into the imperialist world chain, 'national liberation' was simply turned into a cover for the vile interests of the Russian state. It has not been the only one to use this banner: other states have also adopted it in many different forms, but always towards the same end: the war to the death for the re-division of the saturated world market. These innumerable imperialist wars under the guise of 'national liberation' will be the object of the second part of this article.

Systematising the work of clarification which took place after the degeneration of the Communist International by the fractions of the communist left, the Gauche Communiste de France adopted in January 1945 a resolution on the nationalist movements which concluded thus: "Given that the nationalist movements, due to their capitalist nature do not represent any kind of organic or ideological continuity with the class movements of the proletariat, the latter, if it is to maintain its class positions, must break with and abandon all ties with the nationalist movements".

Adalen 20.5.1991

[1] [3] See our pamphlet Nation or Class and articles in the International Review numbers 4, 19, 34, 37, 42 and 62.

[2] [4] On the other hand the proletarian revolution can never be extended by military methods alone, as was made clear by the Executive Committee of the Soviets: "Our enemies and yours are deceiving you when they tell you that the Soviet government wants to implant communism on Polish territory with the bayonets of the soldiers of the Red Army. A communist revolution is only possible when the immense majority of workers are convinced of the idea of creating it with their own force" ('Calling the Polish People', 28.1.20). Despite an important internal opposition - Trotsky, Kirov, etc - the Bolshevik party, increasingly devoured by opportunism and falling into a false understanding of internationalism, encouraged the adventure of the summer of 1920, which radically forgot this principle.

Deepen:

Heritage of the Communist Left:

International Review no.66 - Editorial

- 2101 reads

Chaos

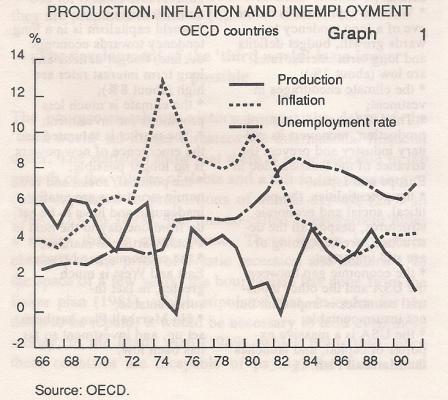

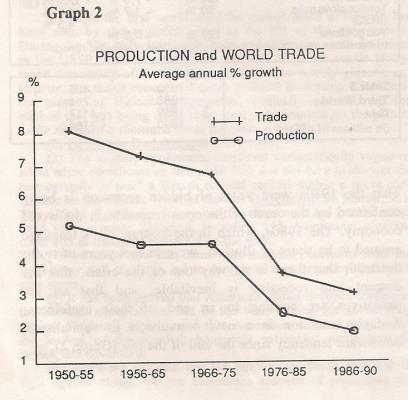

One word is on everybody's lips concerning the present world situation: chaos. A chaos seen as a crying reality or as an imminent threat. The Gulf war has not opened the door to a 'New World Order'. It has merely allowed American capital to reassert its authority, in particular over its allies/rivals in Europe and Japan, and to confirm its role as the world's cop. But society is still caught up in an accelerating whirlpool of disorder, stirred up by the devastating winds of the open recession now hitting the big economic powers.

Four months after the end of the war blood is still flowing in the Kurdish and Shiite regions of Iraq, the fires of war have not gone out. In the Middle East, behind the talk of peace conferences, military antagonisms are exacerbating and Israel has resumed bombing southern Lebanon. In the Soviet republics, armed conflicts are not being attenuated but are on the increase, concrete evidence that the old empire has fallen apart. In South Africa the black population, supposedly freed from apartheid, lives under the shadow of murderous confrontations between the ANC and Inkatha. In the slums of Lima cholera is spreading, interspersed by the bombs hurled by the Stalinist Shining Path. In South Korea, young people are burning themselves to death in protest against government repression. In India the assassination of the last of the Gandhis reveals the dislocation of the 'world's biggest democracy', which is being torn apart by caste, religious, and national conflicts. In Ethiopia, one of the areas of the globe hardest hit by famine, the collapse of the Mengistu government, which was abandoned by its Soviet protectors, has left the country in the hand of three rival armed nationalist gangs who aim to divide up the country. Yugoslavia is on the verge of breaking up under the pressure of daily confrontations between the different nationalities which compose it. In Algeria young unemployed people dragooned by the fundamentalists of the FIS are being sent to fight the tanks of the FLN government. In the ghettos of Washington, Bruxelles or Paris there has been a series of riots and sterile confrontations with the police. At the heart of Europe, in what used to be East Germany, capital is ready to throw nearly half the workforce onto the dole...

The ruling class cannot understand why society, 'its' society, is plunging irreversibly into a growing disorder in which war vies with poverty, dislocation with despair. Its ideology, the ruling ideology, has no explanation. It only exists to sing the glories of the existing order. In order to maintain its grip, it can only resort to lies and deliberately organized confusion. A confusion which expresses both the stupid historic blindness of the decadent bourgeoisie and the lying cynicism that it is capable of when it comes to protecting and justifying its decrepit 'order'.

War, as we have been reminded in the most horrible way by the events in the Gulf, remains the most tragic expression of this reality, in which organized lying goes hand in hand with the most barbaric chaos.

The Balance sheet of the Gulf war

With the most abject cynicism, the ruling classes of the Coalition countries, the American government at their head, have set about the task of making a travesty of the Gulf massacre. When the eastern regimes collapsed, they made a huge song and dance about the triumph of 'western democratic freedoms' over Stalinist obscurantism; but when it came to the Gulf war they organized the most colossal operation of lies and disinformation in history[1]. An operation marked both by the scale of the means used (the American government had at its disposal, among other things, a television network disseminating its poisonous propaganda 24 hours out of 24 all over the planet) and by the enormity of the lies themselves: Michael Deaver, former 'communications' advisor to Reagan and now a secretary general linked to the White House clearly defined the object to be attained: the war had to be presented as "a combination of Lawrence of Arabia and Star Wars"[2].

This was done. The TV screens were inundated with images of the most sophisticated weapons and everything was done to give the impression that it was all a big Wargame. Not one picture of the victims of the deluge of fire which fell upon the Iraqi soldiers and civilians was allowed to disturb this ignoble spectacle of a 'clean war'.

The balance sheet of the war in Iraq is atrocious nonetheless. We will never know the exact number of victims on the Iraqi side[3]. But all the estimates count in hundreds of thousands. Probably nearly 200,000 killed among the soldiers: young peasants and workers, enrolled by force, a gun in their back, lined up en masse in front of the enemy, with the Republican Guard behind them, ready to shoot any deserters[4]. Nearly two thirds of the soldiers killed died during the aerial bombardments, buried alive in their bunkers; most of those who died during the land war were coldly massacred while trying to retreat. In the civilian population, the bombs must have taken a similar toll among the children, women, old people and others who escaped the forced enlistment.

The country has virtually been razed to the ground by the war. All the infrastructures were hit. "For the period to come, Iraq has been thrown back to a pre-industrial age" declared a UN commission of enquiry sent to Iraq in March. The state of the hospitals and the lack of medication will condemn to death thousands of wounded and the victims of epidemics resulting from the lack of food and water. This is the first result of the operation carried out by the 'heroic armies' of the western powers.

To this atrocious balance sheet you have to add the victims of the massacres of the Kurds and the Shiites.

Because at the very time that the American government was organizing the grotesque spectacle of a patriotic orgy in New York, in which the 'victors' of the Gulf butchery paraded between the skyscrapers of Broadway, in Iraq, the Kurdish and Shiite populations were still being subjected to bloody repression by the Saddam government.

What kind of victory was this? Didn't these soldiers go to the Gulf to stop the 'Hitler of the Middle East' from doing this sort of thing?

The reality, clearly confirmed by the declarations of the Kurdish nationalist leaders, is that it was the American government which coldly and cynically provoked the massacre of the Kurdish and Shiite populations[5]. And if Bush's team has kept the 'Butcher of Baghdad' in power it's because, among other things, he was the best man for doing this job, given his well-known talents in this domain. The massive destruction resulting from this repression, this time shown in detail by the media, was used to try to make us forget the destruction wrought by the Coalition. The allied armies, having sat doing nothing while this new butchery was going on, were now able to appear on all the TV screens of the world in the role of humanitarian saviors of the Kurdish refugees (see in this issue, 'The massacres and crimes of the 'great democracies'').

The barbarity of militarism and chaos, travestied by a huge machinery of ideological manipulation. This is what the Gulf war was, and this is the future that it announces.

For the exploited classes of the region, in uniform or not, the balance-sheet of the war is one of carnage in which they participated only as cannon fodder, as guinea-pigs for testing the efficiency of the latest and most sophisticated weapons. For the world proletariat, it is a defeat. Another crime by capital which it was unable to prevent. But it is also a lesson, a reminder of what lies in store if it does not manage to get itself together and put an end to this society.

The real victory of American capitalism

Things are very different for the criminals who provoked this war. For the American government, the mission of the soldiers sent to the Gulf was never to protect the local populations against the exactions of Saddam Hussein. Contrary to what they believed themselves, contrary to the propaganda of their governments, the one and only mission of the Coalition soldiers was to make a violent demonstration of force and determination on behalf of American capitalism. A bloody display of power, made indispensable by the international chaos which was unleashed by the collapse of the USSR and which threatened to undermine the position of the world's leading state[6].

It was the Washington government which wanted and provoked this war. It was its ambassador April Glaspie who, during her discussions with Saddam Hussein at the time when the latter was on the verge of invading Kuwait, declared that the USA was indifferent to the Iraq-Kuwait quarrel, which it considered to be "internal to the Arab world"[7]. Saddam was led to believe that the White House was giving the green light to his hold up.

For American capital, the stakes in this operation were much more important than control over Iraq-Kuwait or oil. The stakes were the whole world, the USA's place in a world tumbling into instability. The Soviet military threat, which had enabled the USA to keep the other powers in its bloc in line for 45 years, was no more. And the dust raised by the fall of the Berlin Wall had hardly fallen to Earth when the German and French politicians were already talking about the formation of a European military force, "more independent of the USA"; in Japan, the call for a revision of the constitution imposed by the American government at the end of the second world war, forbidding the Japanese from having a real army, was again rising to the surface...the main economic rivals and creditors of the USA were claiming a new place in the new situation, a new military and political place more in keeping with their economic power.

For the USA, the Gulf war had to be a brutal reaffirmation of its authority over the world, and above all over Europe and Japan. And from this point of view it was a real victory for the American Godfather, at least in the immediate. The events of the months which followed the war clearly illustrated this.

********************

"The USA, drawing profit from its recent military victory, is in the process of transforming its advantage into a political victory on every continent."[8]

This is how Boucheron, the president of the defense commission of the French National Assembly, recently summarized the international situation. He knows what he is talking about. In Europe, after the Franco-German fanfares that questioned the role of NATO, all the powers have slunk back into line under the pressure of the Americans. The American military has even pushed through the formation of a 'rapid intervention force' within NATO, the bulk of whose forces will be located in Germany, but under the command of America's most faithful ally, Great Britain. For the latter, as for certain eastern countries newly acquired to western influence (Poland, Czechoslovakia), the major fear is of a reunified German capitalism, and they see the American presence as an effective antidote to this menace. The Japanese government has also lowered the tone of all its recriminations, and, like Germany, it has made its 'war contribution' to its great American rival.

As for the countries in the Japanese sphere of influence, they generally look favourably at American pressure in the region because they are afraid of the chaos that would result from Japan's rise to political and military strength. Bob Hawke, the Australian prime minister, openly came out in favour of maintaining American military presence in this part of the world in order to dissuade the regional powers "from acquiring new military capacities which could destabilize the region and unleash a new arms race within it."

The fear of chaos isn't limited to the American government alone. In affirming its role as the world's military and political policeman, the USA is intervening as a 'last resort' against the centrifugal tendencies developing all over the planet, and it is imposing its 'order' with unprecedented arrogance. In Iraq, it dealt with the Kurdish problem in the most cynical manner, ridding itself of the danger of an even greater destabilization of the region, which would have resulted from the political autonomy of a population which lives in five key countries in the region (Iraq, Syria, Turkey, USSR and Iran); in the USSR it refused any real support to the independence movement in the Baltic republics in order to avoid a further destabilization of the former 'Evil Empire'; it also exerts a direct hold over the Moscow government itself, using the pressure of economic aid (see the article 'The USSR in pieces' in this issue); in Ethiopia, which was faced with the threat of breaking up after the victory of the 'rebels', the same authoritarian policeman took it upon itself to organize the London conference which made it possible to form an Ethiopian government around the Tigreans of the EPRDF, and which pressed the Eritrean separatists and the Oromos to cooperate with the new power; in Yugoslavia it's again the US government which has threatened to suspend economic aid if the Serbian bourgeois clique doesn't change its attitude to Croat demands, a situation which is threatening to lead to the breakup of the country; in Pakistan Washington has stopped supplying conventional weapons and a part of its economic aid as long as the Islamabad government fails to provide proof that it is not building nuclear weapons; the American bourgeoisie has even forbidden China from selling Pakistan certain materials that could be used to this end.

This is the 'victory' feted by American capital: the immediate consolidation of its position as the world's number one gangster. It is a victory over its direct competitors, proof of its determination to limit certain aspects of the decomposition which threatens its empire. But the worldwide tendency towards chaos and barbarism will not be held back for all that.

The inevitable slide into chaos

The power of American capital may exert itself all over the planet and momentarily moderate this or that aspect of global chaos. But it cannot reverse the course of the gigantic torrent of blood and filth invading the planet. The new world disorder is not a fortuitous coincidence between different phenomena which are unrelated to each other, and which could therefore be solved one after the other. Behind the present chaos there is a logic, the logic of the advanced decadence of a form of social organization. As marxism and marxism alone analyzed and predicted (the same marxism which the ruling class believes, or would like to have us believe, has been buried with the remains of Stalinism), it's at the very heart of the capitalist relations of production that we can find the key to the impasse which condemns society to this apocalyptic situation.

The economic crisis of capitalism has more and more wiped out the economic capacities of the 'third world' countries. In May 1991, in the aftermath of the huge and destructive waste of the Gulf war, and when the big agricultural powers of the west were deciding to sterilize millions of acres of cultivatable land in order to cope with 'overproduction;', the secretary general of that den of gangsters, the UN, launched an appeal on behalf of Africa, where 30 million people are threatened by famine.

It's this same economic impasse which has led to the collapse of the worm-eaten edifice of state capitalism in the eastern bloc.

It's the economic crisis which, in the industrialized western nations, has led to the industrial desertification of entire areas, generalized job insecurity and unemployment. It's this crisis which is now going through a new acceleration, hitting the centre of the system with full force (see the article on the economic crisis in this issue).

The economic machine is exploiting a diminishing number of workers. A growing portion of society has been ejected from capitalist production, and is being atomized, marginalized, condemned to live by all kinds of little jobs or expedients. This is the generalization of poverty[9]. It's the decomposition of capitalism's social tissue.

Within the possessing class, the economic crisis is also synonymous with sharpening competition. Whether between nations or within each nation, competition is intensifying on the economic and military levels. Blind violence, military language more and more replace economic language. The war of each against all, a feature of capitalism since its beginning, is reaching a paroxysm in this final phase of the system. It's every man for himself in a world without a future.

Capitalist relations of production have become a historic aberration whose survival can only give rise to barbarism, as was the case with slave or feudal relations in their periods of decline. But unlike the past where new social relations (feudal ones after slavery, capitalist ones after feudalism) could begin to develop within the old order, the installation of a new society based on communist relations can only come about on the political ruins of the previous system.

Capitalist logic leads to the economic collapse of the system, but not to its supersession. This can only be the conscious and deliberate act of the world proletariat. If the working class does not manage to take its fight against capital to a revolutionary conclusion, if it does not concretely open up the perspective of a new society, we will not have communism but the barbarous putrefaction of the old capitalist society and the threat of the disappearance of the human species, either through world war, or through decomposition and generalized chaos. The resistance by the proletariat of the central countries against being ideologically dragooned by capitalism has prevented the crisis from leading to world war between two blocs, but it has not been able to slow down the resulting putrefaction of capitalist society. What we are living through today, what is at the source of all the chaos today, is the phenomenon of capitalism simply rotting on its feet, deprived of any perspective.

This is why the action of American capital, however powerful the means it has at its disposal, cannot really reverse this march towards the abyss.

On the level of inter-imperialist conflicts, the Middle East remains an unstable powder-keg in which despite Washington's strongman diplomacy, the explosion of new armed conflicts is inevitable. Already Israel has resumed bombing areas of southern Lebanon and keeps on replying to the pressures on it to 'trade territories for peace' with accusations against Syria for 'devouring Lebanon'[10]. The Gulf war has not brought a definitive peace; it merely demonstrated the means that American capital will use to maintain its supremacy.

As for the economic competition between nations, there are no grounds for thinking that it's going to grow any milder. The aggravation of the economic crisis can only exacerbate it. Here again the action of American capital has functioned as a show of strength to compensate for its weakness vis-a-vis its competitors[11]. "I don't believe that US leadership should be limited to the areas of security and politics. I think that it also has to extend to the economic domain"[12]. This declaration by J Baker does not herald a conciliatory attitude by American capital, but, once again, the method it will use to face up to the economic war.

Whether on the political/military level or the economic level, the perspective is not one of peace and order but war and chaos between countries.

But the tendency towards disintegration also expresses itself within each nation. Whether we're talking about the dislocation of the USSR, of Yugoslavia, of India, of Ethiopia or the majority of African countries, the ravages of poverty and the war to the death between each clique of the capitalist class can only intensify. And a few crumbs of 'humanitarian' aid by the USA or some other power won't reverse the underlying tendencies that are tearing these countries apart.

The class struggle

There can be no struggle against chaos and the dislocation of society unless there is an attack on the source of all this: capitalist social relations. And only the struggle of the proletariat can be an irreconcilable fight against capital. Only the antagonism between labor and capital has the historic and international dimension that is indispensable if there is to be a response to a problem on this scale.

The future of humanity depends on the outcome of the struggle between the workers and the bourgeoisie in all countries. But this in turn depends on the capacity of the workers to recognize the real struggle they have to wage. If the proletariat does not manage to escape from the chaotic whirlpool which causes it to split up along religious, racial, ethnic or other lines, if it does not manage to unite itself by imposing the class terrain as the only terrain worth fighting on, the door will be wide open to the acceleration of chaos and decomposition.

In the underdeveloped countries, where the class is in a minority and has less traditions of struggle, the workers have much more difficulty in escaping the grip of these archaic divisions that are so alien to the class struggle. In the eastern countries, despite all the combativity that has been evident in recent months (in particular with the miners of the USSR and a number of sectors in Bylo-Russia), the working class is weighed down by all the current nationalist, democratic, and of course 'anti-communist' mystifications.

It's in the central countries of western capitalism that the antagonism between capital and labor exists in its most direct and complete from. The working class there represents the majority of the population and its historical experience is the richest, both as regards the mystifications of the bourgeoisie and its own mass struggles. Here are located the decisive battalions of the world proletarian army. The opening up of a new horizon for the workers of the entire world depends on the capacity of the workers in these countries to spring the traps laid by capitalist decomposition (competition faced with the threat of unemployment, conflicts between workers of different national origins, the marginalization of the unemployed), on their ability to clearly affirm their irreconcilable opposition to capital.

****************

The Gulf war gave rise to a deep disquiet in the world population and in particular in the proletariat of the industrialized countries. The end of the conflict engendered a feeling of relief, reinforced by the gigantic ideological campaigns about the new era of peace, the 'new world order'. But this feeling can only be relative and short-lived as the dark clouds of chaos gather all over the planet and upset the 'optimistic' speeches of the ruling class. Nothing could be more dangerous for the revolutionary class than forgetting what the Gulf war was and what it heralds. In the face of the aggravation of the economic crisis and all the attacks on workers' living conditions that go with it, in the defensive struggles that these attacks will provoke, it is crucial that the working class is able to benefit from all the reflection that this disquiet about the war has given rise to. The class will only be able to raise its consciousness, understand the real dimensions of its struggle and carry out its historic task if it looks reality in the face, if it refuses to be 'consoled' by the seductive speeches of the ruling class, and if it rediscovers its revolutionary program and its principal weapon of political combat - marxism.

RV

16/6/91

[1] Since the First World War, the manipulation of opinion has been seen by the capitalist class as the job of the government. During the 30s, with fascism in Italy and Germany, with Stalinism in the USSR, but also and above all with the more subtle Hollywood democracy of the USA, this has become a truly gigantic enterprise, the major concern of every political leadership. Goebbels, the master of Hitlerite propaganda, cynically summed up the method that was being adopted by every government on the planet: "a lie repeated a thousand times becomes a truth".

[2] Le Monde Diplomatique, May 1991.

[3] The military spokesmen remained systematically vague or silent when questioned on this point "We are not here to discuss the pornography of war" a British colonel replied during a press conference on the balance-sheet of the war (Liberation, 26 March, 91). The official figures for losses on the allied side are on the other hand very precise: 236 men, including 115 Americans, plus another 105 in transport accidents on the way.

[4] We know now that there were massive desertions from the Iraqi army and that this led to ferocious repression by Saddam's elite corps.

[5] It has been proved that American planes dropped leaflets in the Kurdish zones at the end of the war, calling for an uprising against Saddam's regime, and that American officers encouraged the leaders of the Kurdish bourgeois nationalist movements to launch this adventure.

[6] When we say that the US Empire undertook this war to fight against chaos, we are sometimes accused of presenting the war as a 'disinterested' action by the American leaders. But we don't think that the USA was acting altruistically just because the most sordid and selfish interests of the USA are opposed to a disorder that would threaten its dominant position in the world. Those who benefit from an existing order always oppose those who call it into question. For a more developed analysis of the causes of the war, see nos 63, 64 and 65 of this review.

[7] cited by Claude Julien in Le monde Diplomatique, October 1991

[8] cited by J Fitchett in Herald Tribune, 12/6/91

[9] Marx's analysis predicting the "absolute pauperization" of society, which during the 1960s was so decried by the so-called theoretical gravediggers of marxism, is today being confirmed in a striking and tragic manner.

[10] American capital has no illusions on this score. Thus, at the same time as it was piling the pressure on Israel to take up a more conciliatory stance vis-a-vis its Arab neighbors, the USA decided to supply the Israeli state with major new stocks of weapons: 46 F-16 fighters, 25 F-15s, in all 700 million dollars worth of weaponry, transmitted directly from the USA's 'arms surplus'. The new weapons stocks will be able to be used by the armies of both states. What's more the USA is financing 80% of Israel's anti-missile missile program.

[11] Without losing a sense of proportion, the USA has been in a comparable position to that of the USSR, with an economy weaker than that of its main vassals. This is to a large extent due to the weight of military expenses which the head of a bloc inevitably has to bear (see 'What point has the crisis reached' in IR 65)

[12] Herald Tribune, 21/2/91.

Geographical:

- United States [7]

General and theoretical questions:

- Imperialism [8]

Recent and ongoing:

- Gulf War [9]

International Situation: The USSR in pieces

- 2381 reads

Who said: "I am aware that we are on the verge of the dislocation of both economy and state"? Gorbachev himself! With every day that passes, the USSR plunges deeper into chaos. The ship of the state is rudderless, and when Gorbachev received the French President Mitterrand in early May, he gave a catastrophic overview of Perestroika, declaring that the soviets are "floundering in the dark", that "the instrumentation no longer works", and that "the crew is disunited". The new prime minister, Pavlov, a worthy representative of the Party nomenklatura, backs this up, saying that the USSR is threatened with "a colossal decomposition"[1]

Russian capitalism's road to disaster

The time, not so long ago, when the USSR's imperialist power made the world tremble, is definitively over. The USSR no longer has the means to keep up its rank as a world imperialist super-power. On the economic level, it never has had. The USSR, despite its under-development, had been able to challenge its American rival (whose GNP in 1990 was three times greater than its own) by concentrating the whole economy in the hands of the state and sacrificing it completely to the needs of its military power.

For decades, the USSR has devoted between 20% and 40% of national income to arms production and the maintenance of the "Red Army". This priority was imposed at the cost of increasing dilapidation in the rest of the economy. The high-tech sectors fell further and further behind. This then rebounded on the arms industry, with the growing technical superiority technical superiority of Western weapons, which still further handicapped Russian military power. Where technology was lacking, or machines unavailable, the brain and brawn of the proletariat was brutally exploited. Under the iron fist of the Stalinist party, the USSR was transformed into gigantic labor camp.

In the end, the USSR was unable to fight the war which it had prepared for so long. Not only were its weapons completely outclassed, the regime's utter rejection by the population made mobilization necessary for war completely impossible.

Faced with the economic collapse, the nomenklatura was forced into an agonizing reappraisal. Economic modernization became an urgent necessity: for this, reforms were required. Gorbachev was to be the standard-bearer of the new economic policy of Perestroika. However, calling into question the economic dogmas which served as a base for Stalinist state capitalism inevitably also meant calling into question the political dogmas at the heart of Stalinism itself, and in particular the dogma of the dictatorial power of the single party.

Far from putting the economy back to rights, Perestroika hastened the collapse of the politico-economic system established by Stalin. Today, the Russian bourgeoisie must confront not only the aberrations of its economy, but the USSR's accelerating plunge into the infernal spiral of economic, political and social chaos.

The question which posed today is that the very existence of the USSR.

The claim of Stalinism, the most brutal form of state capitalism, to represent communism has been the biggest lie of the century. Every fraction of the bourgeoisie, East and West, from extreme left to extreme right, has cooperated to keep it going. The language of Stalinism has prostituted Marxist vocabulary to the service of the USSR's imperialist ambitions, to providing it with an ideological umbrella and an alibi for the regime's exactions. The decomposition of the USSR today has laid bare the truth that revolutionaries have declared constantly for decades: the capitalist nature of the USSR, and the bourgeois nature of the CPSU.

The economic collapse accelerates

For the 1st quarter of 1991, relative to the same quarter of 1990, the state Office of Statistics announced an 8% fall in GNP, a 13% decline in agricultural production, a 40% plunge in exports, and an increase of 27 billion roubles in the federal budget deficit. Western estimates are more pessimistic still, and estimate the fall in GNP at 15%.

The military-industrial complex, the only branch to function with a minimum of efficiency until now, has become to all intents and purposes useless. The USSR has had to trim its imperialist ambitions. It no longer needs more weapons: it hardly knows what to do with the thousands of tanks and the tons of armaments it is being forced to evacuate from its bases in Eastern Europe. Industry's technological heart is almost at a standstill, while it waits for a hypothetical reconversion to the production of capital consumer goods, which would anyway take years. In the meantime, the USSR no longer knows what to do with the now useless technological pride of its industry.

The USSR's traditional customers in the ex-Eastern bloc are turning towards other suppliers, and Russian industry cannot hope to find other outlets for its products, which are technologically completely outdated, of poor quality, and unreliable. Nor is there any prospect of improvement with trade wars raging all throughout the world market.

The structure of the USSR's trade is characteristic of an under-developed country: it is above all an exporter of raw materials, especially oil, and at the same time an importer of food. In 1998, oil and mineral products accounted for 75% of hard currency earnings, while agricultural trade was in deficit to the tune of $12 billion.

Nonetheless, the oil industry has had to reduce production: because it has not been modernized for years, its equipment is constantly breaking down and hampered by a chronic shortage of spare parts. As a result, oil exports fell by 36 % in volume in the 1st quarter of 1991, relative to the same quarter last year.

Agriculture is in a terrible state. The specter of famine has returned to haunt the country, after being pushed back last year by an abundant grain harvest. Cereal production is expected to fall this year by 10%. A shortage of equipment, silos, transport, and machinery, means that 30% of the harvest is simply lost. The USSR will have to make up the deficit on the world market simply to face up to the immediate needs of an already severely rationed population. It will only be able to do so by going still further into debt.

Traditionally, the USSR has always been highly solvent, with a low level of debt. Today, the country is folding under the weight of a debt estimated at $60 billion. Every month sees new delays or defaults on payment, which has recently led Japan to refuse it any new credits. Gorbachev has been reduced to crying for help, begging for aid and new international loans.

But this picture of economic collapse would not be complete if we did not include the destructive effect on the economy of the dynamic of chaos into which the USSR is plunging.

In several republics, production has been virtually brought to a standstill by nationalist conflicts. The situation in the Caucasus is a revealing example. The road and rail blockade that Azerbaijan has imposed on Armenia - many of which have thus been forced to shut down - it has also created a huge bottleneck which encumbers goods transport throughout the southern USSR, forcing the closure of factories right outside the Caucasus region.

The discontent of workers, faced with a constant degradation of their already wretched living conditions, is constantly growing. Stoppages proliferate, massive strikes explode. In recent months, the miners blocked coal production for weeks.

Confronted with this catastrophic situation, the bourgeoisie is paralyzed and impotent. An important fraction within the party is deeply hostile to reform, and is deliberately sabotaging them, further accelerating the breakdown of the economy. The bureaucratic hierarchy's natural passivity is reinforced by the dithering and impotence of the hierarchs in the Kremlin. With decisions being handed down by different fractions at the center, local chiefs prefer to wait to see which way the wind turns rather than take any decisions themselves.

In the meantime, the economy is becoming more and more dilapidated; as it waits for decisions which never come, utter disorganization reigns. Against a backdrop of increasing poverty, the black market has imposed its law of generalized corruption on the whole economy.

The paralysis of the ruling class

The form taken by the counter-revolution in Russia determined its ruling class' mode of organization. The state which emerged from the Russian Revolution, and the Bolshevik Party which had become identified with it, had been devoured from within by the Stalinist counter-revolution. The old possessing classes had been expropriated by the proletarian revolution; a new capitalist class was reconstituted within the Stalinist-Party-State, controlling all the means of production and the whole of social life. The political forms of the one-party state corresponded to the juridical form of state ownership of the means of production.

The members of the Party nomenklatura enjoy privileges which guarantee them living conditions which are simply incomparable with those of the proletariat, which subjected to a grinding poverty. The state ensures a luxurious way of life to those who control its functioning: specially reserved housing, access to shops abundantly stocked with all kinds of consumer goods, especially Western, "company" cars; over and above the salary it brings, a post in the bureaucracy is a source of hidden income from all kinds of traffic and dealing. More than any theoretical analysis, the reality of these facts is ample proof that a privileged class does exist in the USSR, a capitalist bourgeoisie which exploits the working class through the state. The form of exploitation differs from that in Western countries, but the end result is the same.

During the last decades, behind the monolithic façade of the so-called Communist party, quasi-feudal clans, Mafiosi, and dynasties have emerged. Wars between cliques have left their corpses behind, in the course of successive purges. Waste and incompetence reign at every level of the party, its leaders more preoccupied by their rivalries for power, source of wealth and influence, and be every kind of corrupt dealing, than by the management of the productive apparatus.

Brezhnev's death at the end of 1982 was the signal for the outbreak of a "war of succession" in the party, strengthening the centrifugal tendencies within it. When, after the brief interlude of Andropov and Chernenko, Gorbachev's accession to the leadership of the Politburo in 1985 confirmed the victory of the reformist tendency, the collapse of the economy was already clear for all to see, and the decomposition of the ruling party and the development of chaos in general already well under way.

Perestroika proposed to promote economic reform without calling into question either the single party or its control of the state; it only accelerated the collapse of the Stalinist regime. To preserve the unity of the party, Gorbachev had to perform a delicate balancing act between conservative and reformist tendencies; this condemned him to taking no more than half-measures, and so to impotence. Ever since this accession to power, Gorbachev's whole art has been to present a belated recognition that the situation was slipping more and more out of state's control, as a determined policy of bold reform. From one day to the next, Gorbachev has been obliged to accept what he had refused the day before. The aim of Perestroika was to save the USSR and its bloc through a policy of reform; Gorbachev, after trying vainly to maintain in power reformist factions under Moscow's control, has had to abandon any control by the USSR over the countries which has used to form its "glacis" in Eastern Europe. After rejecting repressive methods, he has had to send the army to repress nationalist agitation in the Caucasus and Baku, and against the Lithuanian parliament. After allying with the reformers, he has had to seek support from the conservatives, and vice-versa.

The attempts to gain democratic credibility have been a resounding flop. The elections only highlighted the irredeemable unpopularity of the Party apparatchiks. Nationalist and radical reformers monopolize the votes. In the absence of any food to fill the abyss between the population of the USSR and the Stalinist state. The years of horror, when millions of proletarians and peasants fell under the repression of a corrupt and ferocious state will never be forgotten. Under such conditions, despite all his media skill Gorbachev is incapable of controlling any democratic process. The latest referendum on the Union is a fine example. After years of preparation, it only entrenched the perspectives of disunity: the Armenians, Georgians, and Balts are hostile to the union, and refused to take part; the vote embodied the continued decline of Gorbachev's popularity, and the growing influence of his reformist rival Yeltsin.

The party is imploding, blurring at the edges. A myriad of new organizations have appeared. The Stalinist nostalgics, in favor of strong-arm methods to restore order, go arm-in-arm with the ultra-nationalist, anti-semites Pamyat. The radical reformers leave the party to found democratic associations. In the peripheral republics, splits have created new "communist" parties on a nationalist basis, confirming the breakup of the CPSU. Opportunism is raging. For many one-time apparatchiks, the only means of survival are populist and nationalist demagogy. Under the flags of various nationalities that are stirring the USSR, new alliances of convenience are being formed between the old local fiefdoms of the CPSU, the milieu of wheeler-dealers that has emerged from the flourishing black market, the reformists ranging from the worst kind of opportunist to naïve sould full of democratic illusions, and the historically archaic nationalists.

Ever-wider regions of the USSR are escaping from central control. The independentists are in power in the Baltic states, in Moldavia, in Armenia. Everywhere, the prerogatives of the central power are being reined in, the ruling nationalism encourages disobedience to orders from the Kremlin, while the local state bureaucracy, confronted with the paralysis of the center, hesitates between immobility and support for the newly emerging local powers. Power centers are proliferating everywhere.

Party and state have fractured from top to bottom. The recent agreement between Yeltsin and Gorbachev on the devolution of central power over management of mines to the republics, and the creation of a KGB under the control of the Russian government is an indication of the impotence of the central power.

The long miner's strike has demonstrated the Kremlin's inability to impose its will and get production going again. Since it no longer has any control over whole branches of the economy, it has no other solution than to leave management in the hands of the various local authorities. The USSR's economy is in the process of disintegrating into different poles. The central government is even beginning to lose control over international trade: several republics have already begun to trade directly with each other and with the West, accelerating the centrifugal dynamic of the soviet economy.

Like the party, the police apparatus which is so closely linked to it is splitting up more and more, putting itself at the service of the new nationalist centers of power. New police forces and nationalist militia are taking place of the old police forces to closely tied Moscow.

Frontiers have been set up within the USSR, defended by armed nationalist militias. Lithuania has set up frontier posts, and its frontier guards have clashed several times with Moscow police, resulting in several deaths. The conflict between Armenian and Azerbaijani militias has not diminished in the least since the intervention of the "Red" Army. Pogroms, war and repression in Baku have caused hundreds of deaths. The "Red" Army has not bogged down, without being able to impose a solution on the conflict. In Georgia, recent clashes between Georgians and Ossetians grow that a new area of tension has opened. Ethnic conflicts are proliferating at the farthest confines of Russia.

Within this context of disintegration, the only structure which has all resisted the overall decomposition, and the loss of control by the central power, and which still makes it possible to maintain some pretense of cohesion within the USSR, is the army. However, the same dynamic which dominates the USSR as a whole, is at work here also. Hundreds of thousands of soldiers repatriated from Eastern Europe find themselves and their families unhoused, living in conditions of real poverty which are all the more resented in that they have just returned from countries with a higher standard of living. This is aggravating the general malaise that has infected the army since the retreat from Afghanistan. There are out and out battles in the barracks between soldiers of different nationalities. Draft-dodging, desertion, and insubordination are becoming commonplace.

The soviet bourgeoisie no longer has the means to conduct a generalized repression. Although its army can still undertake to keep the peace in some regions, its room for maneuver is nonetheless very limited. The repressive apparatus' hesitations over the situation in Lithuania or the Caucasus express perfectly the disarray and impotence of the Kremlin government. Only a few principles, nostalgic for the Stalinist past, still think that large scale repression is still possible without tipping the USSR still faster into civil war.

The proletariat caught in the whirlwind

Neither the widespread discontent, nor the regime's complete lack of credibility, much less the class struggle, lay behind the collapse of the Stalinist state. The discontent is not new, nor is the state's lack of credibility. As for the class struggle, we only have to remark that there was no significant struggle in the USSR before the miner's strike in 1989.

In the name of the defense of communism and proletarian internationalism, generations of proletarians have been subjected to the bestiality of Stalinism, the product of the defeat of the Russian revolution. In rejecting the regime the workers of the USSR have also rejected all the proletariat's revolutionary tradition, its class experience, leading the descendants of the proletarians of the Revolution into total political confusion, identifying the worst capitalist dictatorship with socialism. In reaction to Stalinism, soviet workers' hopes for change have turned towards the mythical past of national folklore, or towards the wonderful mirage of Western capitalist "democracy".

The proletariat is suffering even more strongly from the devastating consequences of this dynamic of disintegration and decomposition because it did not overthrow the Stalinist regime itself. The democratic illusion has no historical roots in Russia, and remains the domain of petty bourgeois intellectuals. The proletariat is more receptive to populist and nationalist demagogy. The weight of nationalism on the proletariat is due both to the backwardness of Russian capitalism which was unable to integrate the populations colonized by Tsarism, given its economic weakness, and to the gut reaction against the central government, which is the symbol of years of terror and dictatorship.