International Review no.55 - 4th quarter 1988

- 3497 reads

Grupo Proletario Internacionalista: Crisis and workers’ struggles in Mexico

- 2069 reads

We are publishing here an article from the Grupo Proletario Internacianalista of Mexico. We have already presented this group in previous issues of the International Review (nos. 50, 52, and 53). This article on the situation in Mexico expresses the position of the GPI, and was published in Revolucion Mundial no.4 just before last July's presidential elections in Mexico.

In publishing this text, we intend to express our agreement with its political content, but above all to publicize the extent of the economic disaster that has overtaken Mexican capitalism, along with three quarters of the planet. Our aim is to denounce the appalling conditions that millions of human beings live in today. The text from the comrades of the GPI demonstrates that capitalist barbarism is not a fatality, and that the working class, -- even if its strength locally cannot be as great as in the industrial concentrations of North America and Europe -- is struggling against poverty, and coming forward as the only social force able to offer a perspective other than barbarism to all the unemployed and poverty-stricken masses in these countries. As in the rest of Latin America, the Mexican proletariat is fighting back, and is being lead to develop the same weapons as its class brothers on other continents, against the same obstacles: first and foremost, the left parties, the trade unions, and state repression.

The reality of workers' combativity in Mexico is confirmed by the results of the latest presidential elections, where for the first time in 60 years the candidate of the PRI (the party in power) only won 50% of the votes, in utter confusion, and clearly thanks to electoral fraud. His opponent, Cuauhtemoc Cardenas who also comes from the ... PRI, was supported by a coalition of left-wing parties -- the CP and the Trotskyists among them. The bourgeoisie has tried, and appears to have succeeded, to create a left-wing political force around Cardenas on the basis of such themes "democracy against corruption and electoral fraud", nationalism against repaying the Mexican debt, against the "dictatorship of the IMF" or of American imperialism, in order to derail an increasing anger and desperation onto the safe ground of democracy. And this new adaptation of the bourgeoisie's political forces in Mexico is accompanied by the development of "independent unionism" (ie of the sole trade union, the CTM), which is the Mexican version of rank-and-file unionism.

In short the Mexican bourgeoisie, following the enlightened advice of the USA, is setting up the political and trade union forces of the left in opposition, in order to mislead the workers' struggles which must inevitably come, towards the democratic mystification already being employed in most Latin American countries, like Chile, today.

In the abyss of a chronic crisis

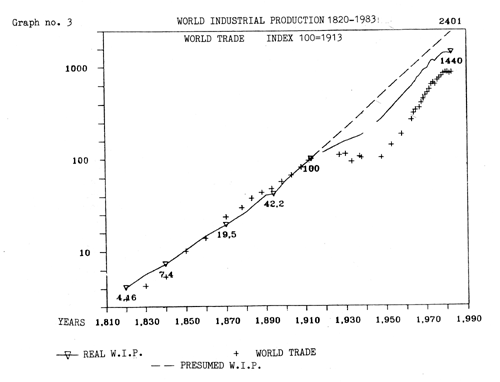

In recent years, the crisis in Mexico has constantly deepened. This situation can only be wholly understood if we take account of the fact that Mexico is an integral part of the world capitalist system, and that it is therefore immersed in the world capitalist crisis which has been inexorably spreading and deepening since the end of the 1960's, in the form of ever deeper and more violent "recessions" (paralysis of industrial and commercial growth) and shorter and less convincing "recoveries".

So whereas the last "recession" in 1980-82 hit the entire world economy, the "recovery" which followed from 1983-86 only affected the great powers, while most countries continued to stagnate. Today, the whole world is on the way to a new "recession", whose effects will certainly be still more disastrous than those of its predecessor.

In Mexico, industry has collapsed since 1982. For five years, the GDP's growth rate has remained negative ... Every branch of industry is stagnant or in decline ... which worsens the situation of the workers. In 1987, "industrial growth remained at a complete standstill"[1].

We will highlight here only three external and visible signs of the deepening crisis in 1987:

1) the weak growth in GDP (1.4%) is far from compensating the previous year's collapse. This demonstrates clearly that production continues to stagnate, due to lack of incentive to invest given worldwide over-production and the collapse of the prices of Mexico's raw material exports (oil, mineral ores, farm produce).

2) an annual inflation rate of about 159%.

Since the internal market is exhausted, the government is trying to reanimate it by increasing its expenditure. To do so, it is printing money to pay its employees ... which allows the latter to go on buying, getting credit, etc ...

However, the uncontrolled production of paper money has the same effect as the production of any other commodity at lower cost: its value falls. And the more paper money is in circulation, the more its value is depreciated in relation to other commodities; in other words, commodities cost more.

Although it is true that all commodities cost more, their prices are not all increasing in the same proportion; the price of labor-power (ie wages) in particular is trailing far behind that of other comodities: a mechanism well known to workers, and which is used by the capitalist class to appropriate improved profits via falling wages,

For capital however, the trouble is that each rise in prices provokes a renewed acceleration in the issue of paper money ... and so on, provoking an "inflationary spiral", where the quantity of money grows at the same accelerating rhythm as its value falls, to the point where prices are rising so fast -- from day to day, or even from hour to hour (What is known as "superinflation") -- that money becomes totally worthless, since it no can longer be used to measure the value of goods, for trade, for savings, or for anything else.

In this way, the mechanism used initially to reanimate the circulation of commodities is transformed into its opposite: yet another obstacle to this circulation, which deepens stagnation still further.

Inflation is a clear example of the way in which the measures of political economy applied by national states today are able to contain the crisis momentarily, but not to put an end to it. During the last few months, the Mexican economy has been heading straight for "hyper-inflation"[2].

3) the fantastic rise in Mexican stock-exchange values over a period of a few months, and their subsequent collapse in October 1987, at the same time as stock exchanges all over the world.

The collapse of the Mexican stock-exchange and its simultaneity with that of others throughout the world is not mere coincidence: its fundamental causes were the same; it has highlighted the complete interpenetration of the world economy. The growth of the world's main stock exchanges (London, Tokyo, New York) during the last two years has been out of all proportion to industrial growth. Capital has been abandoning productive investment, in favor of speculative financial operations, a sign that the "recovery" begun in 1983 was drawing to a close. Since the world's main financial centers were on the way to becoming saturated, capital began to flow into the less important ones. And so, during 1987, a lot of capital "returned" to Mexico, not to be invested in industry, but essentially to be placed on the stock exchange, in the emission of shares, appropriating the money of other investors, who bought up shares, attracted by the promise of juicy profits (promises which went as high as 1000%). Thus, purely through the interplay of supply and demand, encouraged by the press and the government, the Mexico stock exchange grew by 600% in a few months ... only to collapse with the rest of the world's stock exchanges when it became apparent that neither world nor national production had grown sufficiently, and that the promised profits were unreal; the Mexico stock exchange lost 80% of its value. The only ones to make a profit were those who had access to and manipulated inside information, and so were able to sell their actions quickly and keep their cash, while the rest were ruined.[3]

And so, in today's conditions of over-production and saturated markets, industrial production is blocked, while capital turns to seeking profit in speculation.

Faced with this situation, the Mexican government decided in December 1987 to adopt a new economic program, baptized the "Pact of Economic Solidarity". The state recognized the failure of previous plans for dealing with the crisis (which goes to show that previous optimistic official declarations were lies), and that the crisis is continuing and getting worse, making it necessary to retreat in as good an order as possible, by "distributing" (insofar as the state is able to do so) losses among the different sectors of capital, but essentially by increasing still further the exploitation of the working class.

To launch this program, the state mounted an enormous ideological campaign, broadcast by every possible means, to convince workers that they should accept it, that the "pact" would be a basis for solving the "nation's problems", that there should be "solidarity" among the different sectors of society, in other words that they should accept still more sacrifices to save the capitalists' profits.

The "solidarity pact" is in the form of an anti-inflationist program, similar in some ways to those adopted in countries like Argentina, Brazil, or Israel. Starting with a general, sudden and unexpected price rise, combined with a wage freeze and a drastic diminution in state spending (5.8%), it aims, little by little, to rein in inflation. This means nothing other than a new and terrible shrinkage in domestic trade, even if it is "regulated" by the state, and more company closures, starting with those owned by the state (closures which will in turn hit private industry).

In fact, during the last five years a whole string of semi-nationalized industries have been sold off at knock-down prices. This process, which the government calls "disincorporation" has hit some 600 companies, and in the case of some big ones like Fundidora Monterrey has brought in its wake the liquidation of a series of subsidiaries and suppliers. The "pact" has simply accelerated this process: during the "pact"'s first three months alone, the government authorized the liquidation of 40 companies (the most important being Aeromexico, employing 10,000 workers) and the sale of 40 others (including the Canaena, Mexico's largest copper mine).

This is what the deepening crisis means: the acceleration of the process of destruction/devalorisation of capital, through the material destruction of means of production or their devalorisation, and through falling wages and massive redundancies (along with increasing rates of exploitation for those workers still in a job). Capital is trying, on this basis, to compensate the fall in profits, by expropriating more surplus-value in relation to invested capital, which means putting cheaper, more competitive products on the international market.

With the "solidarity pact" the working class' living conditions can only get worse. Physical exhaustion at work, unemployment and poverty are increasing. Capitalist exploitation is becoming daily more intolerable.

The situation of the working class in Mexico

In Mexico, as in the rest of the world, the proletariat's situation is getting worse. The bourgeoisie's own figures are only a pale reflection of this reality.

The collapse of the productive base is matched by massive unemployment. It is calculated[4] that 4 million workers have been laid off in Mexico over the last 5 years, which, when combined with youngsters looking for work but unable to find it, brings us to 6 million unemployed. The DINA group, which once employed 27,000 workers, is a dramatic example: in 1982 it only employed 10,000, and in 1987 only 5,000; the "pact" will cut the number still further, especially since the decision to sell off seven subsidiaries (accompanied of course by appropriate "restructuring" measures, which will mean more lay-offs for the workers).

The immediate result of the "solidarity pact" was the loss of 30,000 jobs (13,000 in the state sector, and 17,000 in the semi-nationalized industries)[5], and the redundancies are continuing.

To growing unemployment, is added the fall in the working class' real wage. We can get some idea of this fall if we look at the evolution of the "distribution of income", wages as a percentage of the GDP. In 1977, wages represented 40% of GDP; in 1986, they were 36%, and in 1987 hardly 26%. Everyone recognizes the collapse of the minimum wage (officially, its purchasing power only fell by 6% in 1987). It should be added that there are an incalculable number of workers who earn still less than the minimum, for example the municipal employees of Tampico [a port of some 230,000 inhabitants on the Atlantic coast, ed.] who went on strike to demand ... the minimum wage. The higher wage brackets are also falling: in 1976, for example, a university teacher earned 4 times, and a university worker 1.5 times the minimum wage; today, they earn 2.8 and 1.2 times the minimum respectively[6]. Other examples: wages in the maquiladoras[7] in the Northern frontier, regions have fallen to the point where they are the lowest assembly-line wages in the world; old-age pensions are only half the minimum wage. Researchers are forced to recognize the effects of the reduction in wages on workers' living conditions. Thus, for example, "between 1981 and 1985, low-income families (40% of the population) have suffered a serious decline in their standards of nutrition, to the point where they are below the level recommended by the FAO"[8]. It is also recognized that 100,000 young children die every year in Mexico for reasons directly due to poverty (malnutrition, parasitic diseases).

The "pact" means a new, brutal and two-fold reduction in wages: on the one hand, cuts in government spending will mean cuts in the social wage -- education, health and other services; on the other, the basic mechanism for controlling inflation relies, as we have just said, on slowing down the rise in wages in relation to the rise in prices, or in other words on the falling purchasing power of wages.

To massive unemployment and falling wages should be added the conditions of work imposed by capital: contracts are being broken everywhere with the replacement of permanent jobs by temporary ones (with the loss of all kinds of advantages such as holidays, etc), increases in work rates, all measures that the "pact" simply accelerates. One recent example is that of Nissan, where the bosses wanted to do away with the workers' "leeway" of ten minutes at the beginning and end of each shift, which came down to producing an extra 12 cars per day.

Finally, as a direct result of economies in capital invested (which also implies economies in security measures), and of the increase in work rates, there is an increase in the number of "accidents" at work which is even recognized officially. A recent case is "accident" of 25th January in the Cuatro y Medio de Cohauila mine where 49 workers lost their lives; no matter how the authorities try to hide the causes of the collapse that buried the miners, the facts are there: the collapse was due to the explosion of an electrical transformer which in its turn caused the explosion of a highly concentrated pocket of firedamp; this highlighted both the lack of proper maintenance of mine machinery, and of a team to detect and extract the gas. The other miners were afterwards forced to go back to work in the same conditions.

There it is. The whole Mexican situation reveals the same features of world capitalism. A chronic crisis, which for the proletariat means still more exploitation, still more poverty, and even its physical destruction. A growing social barbarism; a barbarism with no end to it. No "restructuration", no "program" will get capitalism out of such a situation. For the world capitalist class (including its Mexican fraction), the only solution to the crisis would be a new world war as a means of destruction of the means of destruction a thousand times greater than before; this is the only basis which might, hypothetically, open the way to the development of new productive forces and a new division of the world market amongst the victors[9]. But the present capitalist crisis, with the aggravation of living and working conditions it involves, is making things move in the minds of millions of proletarians. It is awakening their will to struggle against capitalist exploitation, a will which has been crushed under 50 years of triumphant counter-revolution, but which is reappearing on an international level with the massive strikes since the end of the sixties. The Mexican proletariat is also a part of this proletarian awakening.

The class struggle in Mexico

There is only one worldwide working class. Its condition as the exploited class and producer of all material wealth unites it with the sane historic interests and objectives: the abolition of wage labor. The chronic crisis sweeping across the whole planet makes it still more obvious that the conditions of capitalist exploitation are the same in every country throughout the world, whether they be "developed", "under-developed" or "socialist", and clearly demonstrates the united, international nature of the working class. In this sense, the struggle of the proletariat "in Mexico" is only a small part of the united worldwide proletarian struggle, even if for the moment this unity is only determined "objectively" because of the increasing exploitation which everywhere pushes workers to resist, and still demands a "subjective" unity, ie conscious and organized by the working class at an international level, in order to carry out its revolutionary objectives.

In the previous issue of Revolucion Mundial, we demonstrated that the Mexican working class is fighting back against capital's economic attacks, and that despite its weakness, its limitations, and the obstacles that capitalism puts in its way, this fight back is part of the wave of struggles that has swept the world since 1983. Its lynchpin was the strike of 36,000 electrical workers in early 1987, which although it remained under union control managed to involved hundreds of thousands of workers from other industrial branches in one demonstration, just as other fractions of the working class were struggling in other parts of the world.

During the first three months of 1988, Mexico has witnessed a new working class upsurge, which even though they are on a smaller scale than those in other countries nonetheless express the same general tendencies, the same difficulties, and the same confrontation with the attacks of the state.

Strikes have broken out throughout the country almost simultaneously, because it is the "wage round" period of the year, both in the "state" and the "private" sector: in the car factories at Ford in Chihuahua, at General Motors in Mexico City, at Volkswagen in Puebla and shortly afterwards at Nissan in Morelos; in other industries, such as the Quimica y Derivados and the Celanese in Jalisco; at Central de Malta and the public transport system in Puebla; Productos Pesceros at Oaxaca; Aceitera B y G in San Luis Potosi; amongst the dockers of the port of Veracruz; amongst the pressed steel workers at CASA in Mexico City. A strike also broke out in the country's 25 insurance companies and 10 universities. In the regions of Tamaulipas and Sinaloa, the employees of the Ministry of Agriculture stopped work; the workers on the Mexico City underground called a protest demonstration. And the employees of the Social Security held stoppages in Mexico City and several other provincial towns. All these strikes and stoppages revolved around the central demands for wage increases and an end to the massive redundancies planned by capital. But all these strikes remained isolated, under the iron control of the unions, both "official" (Labor Congress) and "independent" (Bureau of Coordination) -- with one exception: the movement in the Social Security (IMSS), of which we will speak later.

The unions' control over the movement was expressed, for example, in the agreements that they put forward masquerading as "workers' solidarity", but whose only aim was to put down the struggles: for example, the agreement by the five car industry unions to make each worker still at work give 1,000 pesos a week to "support" those on strike; they thus eradicated the possibility of creating any real solidarity (which can be nothing other than the strike's extension to other factories irrespective of their industrial branch), pretending that passivity and isolation was in fact "support". A similar example is that given by the SUNTU (a sort of federation of unions of university workers), whose work was essentially to keep each strikebound university within a framework of separate negotiations.

The unions are always the first barrier in the way of the workers developing their struggle. The union is capital's main tool keeping the workers' struggles within the framework of isolated protests, preventing them from taking the road towards their coordination, and unification, thrusting aside their divisions by industrial branch or geographical region (which is possible today thanks to the simultaneity of the struggles themselves).

This is what gives the Social Security workers' struggle its importance; their efforts to rid themselves of the union yoke were an example to other workers, on the point of entering into struggle at the same time.

Already in 1986, different categories in the IMSS had mobilized in different parts of the country; now these categories all mobilized together: nurses, doctors, ancillary workers, etc.

The immediate reason for this new struggle was the combined unions and employers sabotage of the contract review, demanding that the workers be satisfied with the "wage rise" allotted by the "pact of solidarity". In reply, the workers began spontaneous stoppages in every hospital in the capital, as well as in certain provincial towns, outside and against the official union; the shop stewards were explicitly identified with the government. The height of the movement was the militant demonstration by 50,000 workers on 29th January, which attracted the solidarity of workers from other parts of the Health Service, as well as of the "colons" (slum-dwellers). The workers also tried to give themselves a representative organism, but this did not come to anything in the end.

The movement was bitterly attacked by the state. The media merely repeated that the authorities and the unions would accept no demand made outside "the legal and trade-union framework". Many workers were threatened with disciplinary measures at the workplace; more than a hundred were suspended. The police also came to repress those who barricaded the roads during the strike. But it was capitalism's left that took charge of the most important part of the attack on the workers.

Each time that the workers tried to get out of trade union control, it was the left of capital that went to work to put forward a policy -- every bit as bourgeois and dangerous for the workers -- of "democratizing" the union, or of creating an "independent" one. Each time, the left attacked on two fronts: on the one hand trying to form a "front" to "put pressure on the union to make it do its job" ... as if it had not already done its job when it openly repressed the workers. On the other hand, by undermining the movement "from the inside", by leading the workers' efforts to organize themselves off towards the creation of a "coordination" which, far from putting forward the needs of the movement, gave itself the aim of "winning positions within the trade union in order to democratize it". At the same time, the capitalist left tried to reinforce the sector's strong corporatist tendencies, in order to keep it isolated from the other workers on strike. And this was how the struggle was exhausted without winning one of its demands.

Nonetheless, the struggle in the IMSS has once again demonstrated not only that the union, as an organ of capital, can very well openly suppress the workers' struggle, but more importantly that it is possible to mobilize without relying on the union. This is therefore a step forward, an example for the whole working class to follow, even if sectional and regional differences, and the isolation of the struggle, still remain to be broken.

In short: the strikes that we have just been through in Mexico, reflect the same tendencies that can be made out in workers' struggles in other countries:

-- firstly, a growing tendency towards simultaneity: series of strikes, breaking out everywhere, in different branches at the same time;

-- attempts to break the control of the union, and in the most exemplaly cases, attempts by the workers to organize the struggle themselves;

-- to a lesser extent, some demonstrations of solidarity between different branches.

These strikes are facing a concerted attack by the state, with the trade unions in its front line. The unions have not managed to prevent the strikes from breaking out, but on the other hand, they have succeeded in keeping them isolated, and within the framework of the demands a "particular" to each sector. Should the workers be determined to get rid of it, union control is certainly capable of changing its mask; it may replace an "official" union with one more "radical", more "independent", or present as "self-organization" something that is merely an empty shell without the slightest proletarian content, and which plays the same role as the union: the isolation and exhaustion of the struggle.

At the same time, the attack is concretized by a constant strengthening of the repressive apparatus, a massive use of police power against workers when they mobilize, and direct repression of certain struggles.

And to all this should be added the campaigns designed to maintain the bourgeoisie's political domination of the workers thanks to the game of "democracy"; today in Mexico, this question is being used to the full in the face of the coming presidential elections. In this way, the opposition parties have tried to channel the discontent at the "pact of solidarity" into the elections, in particular by calling marches supposedly against the "pact", but which in fact end up asking support for some candidate or another. Lastly, the bourgeois state wants to appear before the workers as something untouchable and unmoveable.

The latest expression of the recent wave of strikes in Mexico was the Aeromexico strike. More than 10,000 workers (essentially ground staff) rose against the company's proposal to decommision 13 aircraft, which would have brought a series of lay-offs in its wake.

Confident that the union had the workers well in hand, the government did not, contrary to what had been feared and to what is usual in "para-state" companies, "requisition" the company,(which would have meant the arrival of the police and the scabs). Instead it let the strike break out, only to declare, after a few days and on the pretext that "the strikes had caused too many losses" that the company was bankrupt, leaving thousands of workers without a job.

It is obvious that on this occasion the state wanted to "give a lesson" not only to this branch but to the whole working class. The message, abundantly spread by the capitalist media, could not be any clearer: "Strikes are useless ... workers will have to resign themselves to the inevitable".

But for the working class, the lessons left by these strikes are very different, and so are the perspectives that we should draw out from them.

Perspectives for the workers' struggle

For the moment, the strikes are over. But there is no need to be a magician to see that the workers will be pushed to resist as the cri sis deepens, and it will not be long before the struggle begins again. In fact, throughout the world the tendency is towards a multiplicity of strikes, even if they are still on the defensive, still strikes of resistance to capital's economic attacks.

However, as the strikes spread to draw in other fractions of the working class throughout the world, and to reveal attempts at active solidarity, to break with the unions and to organize the struggle autonomously, capital's counter-attacks will also be increasingly bitter. Confronting an enemy less and less s ready to accord any of their demands, each new struggle will become harder, will demand of the workers greater determination and energy. Each national fraction of world capital will try to crush the struggle by any means at its disposal so as not to risk losing an inch of ground in the competition for markets.

For a long time already, isolated strikes of resistance have been unable to wrest the slightest satisfaction of their demands from capital. Today, only a truly massive and militant struggle, involving hundreds and thousands of workers can hope to halt momentarily capital's economic attacks, and even this is becoming more and more difficult. This means that as long as the chronic crisis continues, the development of defensive struggles cannot bring about any real and lasting improvement for the workers. Consequently, the struggle can only advance through greater extension, the deepening of its aims, the passage from isolated struggles for particular demands to a general and organized struggle for class objectives. The present efforts at solidarity and self-organization demonstrate this tendency.

But the defensive struggles will not take this direction automatically as a result of the crisis; it will demand a further effort by the working class to regain, assimilate and pass on the experience of its struggles, both recent and historic: the experience that demonstrates the need to rise from the struggles whose aim is simply to get rid the effects of capitalist exploitation, to the struggle that aims to put an end to this exploitation definitively. To do so, the class will have to overthrow the bourgeoisie, seize political power, and install the dictatorship of the proletariat. This demands therefore that the proletariat raise itself to a consciousness of its historic revolutionary objectives. This is a collective effort of the entire working class, within which the revolutionary organization (and later the World Party), as the most active and conscious part of the class, has a determining role to play. In the end, the result of the combat for class consciousness will be decisive in the class confrontations to come.

Ldo. May 1988

[1]See Revolucion Mundial nos. 1 and 3. The GDP (Gross Domestic Product) is a figure of bourgeois economy, which to an extent expresses economic growth from one year to the next. However, it should be born in mind that, given the "scientists'" theoretical assumptions (division of the economy into industrial, agricultural and financial "sectors"; added value, etc) and their manipulation of the results, this kind of figure presents reality in a manner deformed according to the interests of capital.

[2]The tendency to "hyper-inflation" was obvious for anyone capable of adding two and two:

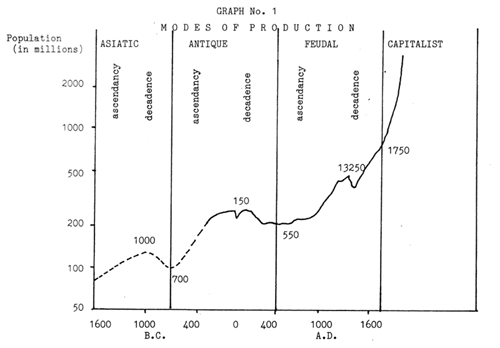

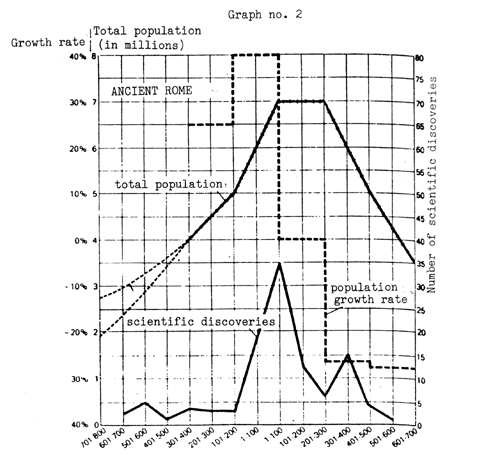

(GRAPH)

Inflation (annual percentage) / year

[3]In the next phase of the game, the winners also recover at rock-bottom prices the actions issued, as well as keeping their cost. This is why the stock exchange seemed afterwards to recover to some extent.

[4]According to data from the SIPRO (Servicios Informativos y Procesados AC), which coincides with that from other sources.

[5]Official report on the "pact" from the Secretariat of the Presidency, March 1988.

[6]Uno mas Uno, 27/01/88.

[7]The "maquiladoras" are generally electronic and automobile component industries set up by foreign capital, whose output is destined for the US market (which is why they are usually installed on the northern frontier). The table below shows the wages paid in these "maquiladoras" in relation to those in other countries:

|

Average basic hourly wage |

1986

|

|

South Korea |

$3.65 |

|

Taiwan |

$2.95 |

|

Singapore |

$2.30 |

|

Hongkong |

$2.05 |

|

Jamaica |

$1.25 |

|

Costa Rica |

$1.05 |

|

Dominican Republic |

$0.95 |

|

Mexico |

$0.85 |

|

Source: El Financiero, 10/08/87 |

[8]Le Monde Diplomatique, Spanish version, Dec 1987

[9]The Mexican bourgeoisie took part in World War II, for example, not so much with troops (whose .presence· was purely symbolic), but by supplying raw materials. Afterwards, it benefited from the period of post-war reconstruction, which made possible the country's rapid industrialization.

Geographical:

- Mexico [1]

Heritage of the Communist Left:

Recent and ongoing:

1918-1919: seventy years ago On the Revolution in Germany

- 2457 reads

Introduction

70 years ago the proletariat in Germany threw itself into the most important experience of its history. It undertook the task of carrying forward the flame of the revolution, which the Russian proletariat had lit in 1917, and of spreading it to Western Europe.

Everywhere in Germany workers' and soldiers' were founded in the first days of November. The example of the workers in Russia, which was also taken up by the workers in Austria and in Hungary, and to a certain extent in Italy as well, was to serve as a magnificent stimulus.

Revolutionaries had put all their hopes on Germany, because, more than any other section of the proletariat, the working class there, due to its key position in Europe, could come to the help of the isolated workers in Russia, by smashing the capitalist class in Germany and thus opening up the road towards world revolution.

The fate of the international working class, even of the whole of humanity, lay in the hands of the working class in Germany. Its capacity to push through a victorious revolution, to conquer power and to maintain it was to be decisive for the further course of the struggles in Russia, in the centre of Europe and on a world scale.

But as gigantic as the responsibility and the task of the working class in Germany were, just as tremendous were the obstacles that it had to push aside, because the proletariat was facing a capitalist class which was well-experienced and well-equipped in facing the working class. As, a ruling class of an industrialized country it was capable of mounting a much fiercer resistance than the bourgeoisie in Russia, which had been chased away by the proletariat relatively rapidly without any bloodshed.

All the revolutionaries were aware of this. Thus Lenin wrote on 23.7.1918: "For us it was easier to start the revolution, but it is extremely difficult for us to continue and accomplish it. And the revolution has tremendous difficulties in coming about in such a highly industrialized country as Germany, in a country with such a well-organize bourgeoisie" (Lenin, Speech at a Moscow Conference of delegates of the factory committees, 23.7.1918).

And seeing what was at stake, revolutionaries in Russia in particular were ready to come to the help of the workers in Germany. Well before the actual outbreak of the workers' rising, Lenin wrote on Oct.1.1918: "For the German working masses we are preparing ... a fraternal alliance, bread and military aid. We will all put our life at risk, in order to help the German workers push forward the revolution which has started in Germany" (Lenin, 1.10.1918, letter to Sverdlov, in: Lenin, On Germany and the German Workers' Movement, Berlin, 1957, p. 448).

But the German bourgeoisie also got the support of the ruling class of the other countries, in particular of the ‘winners' of the First World War, who were scared by the specter of the spread of the proletarian world revolution. Whereas before the various national bourgeoisies had been trying to rip off each others' territories on the battlefields of the imperialist war at the expense of more than 20 million dead and an uncountable number of injured, they were now ready to close their ranks vis-a-vis a working class fighting on its class terrain. Once again it turned out to be true that the ruling class, divided by its very nature, can unify in a revolutionary situation in order to stand up against the working class. The ruling class in Germany had also started quickly learning the lessons of the revolution in Russia, in order to fight against the working class on the basis of this experience.

The onslaught of the working class in Germany against the capitalist regime was blocked by the bourgeoisie. More than 20,000 workers were massacred and more injured between 1918 and the begenning of the 1920s. The bourgeoisie in Germany managed to decapitate the leadership of the proletariat. Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Liebknecht were killed by the SPD-organized Freikorps in the January rising of 1919. Even though the KPD, which had been founded in the heat of the struggles in Dec .1918/Jan.1919 was one of the first to declare itself against the unions and parliament, it stepped into these struggles with insufficiently elaborated programmatic positions, was organizationally ill-prepared, and split up a short time after its foundation. Politically weakened, the proletariat was not able to overcome these weaknesses in the course of its struggles.

The attempts to extend the revolutionary wave beyond the Russian borders were blunted through the defeat of the working class in Germany. This was to have catastrophic consequences for the international working class, since, as a result of the defeat of the struggles in Germany, the bourgeoisie was able to begin a worldwide offensive against the working class. This placed the workers in Russia in an even more isolated situation in face of the attacks of the White Armies. The smashing of the revolutionary struggles in Germany, and through this the isolation of the workers in Russia, thus accelerated the defeat of the revolution in Russia, where the backbone of an isolated proletariat could also be broken.

The struggles in Germany and Russia: the same force dynamized them, the same perspective united them

The struggles in Germany were stimulated by the same driving force as the struggles of the working class in Russia.

After the mobilization of the working class in Germany on the battlefield for the imperialist war aims of the German bourgeoisie, which had been facilitated through the betrayal of the parliamentary fraction of the SPD in August 1914, and after the unions had maintained a relative calm in the factories and in the working class as a whole in the first years of the war, the working class, from 1916 on, slowly began raise its head. The wave of wildcat strikes which from winter 1917 on began to shake the armaments industry, the growing resistance against war and its miseries. These workers' struggles, which were clearly under the influence of the Russian revolution, showed that in Germany too the working class, despite a significant weakening through the war, was not yet defeated. On the contrary, it was in the process of standing up against the policy of ‘burgfrieden', class peace on the home front. This strike wave thus smashed the social peace which the unions and capital had agreed on at the beginning of the war. This agreement not only irreversibly brought the unions over into the camp of the bourgeoisie, but also constituted an irreplaceable pillar of the domination of capital.

The movement of Nov. 1918 put forward the same demands as had been raised a year before by the workers in Russia: bread and peace. The movement against the war began not at the front, but in the factories.

Its central unifying point was therefore the struggle against hunger, against the continuation of the war. It was necessary to bring down the ruling class in order to satisfy these demands.

That's why the Spartakists and Rosa Luxemburg summed up the goal and the first measures which would have to be taken in the following terms:

"The goal of the revolution (the abolition of the rule of capital, the achievement of the socialist order of society), clearly indicates its path, the task dictates the method. All power in the hands of the working masses, in the hands of the workers' and soldiers' councils, securing the work of the revolution in face of its cowering enemies: this is the orientation for all the measures of the revolutionary government:

-- the further development and the re-election of the local workers' and soldiers' councils in order that the first chaotic and impulsive gesture of their emergence can be replaced through the conscious process of self-understanding about the goals, tasks and the path of the revolution,

-- the permanent coming together of these representatives of the masses and the handing over of real political power from the tiny committee of the Vollzugsrat (executive council) to the broad foundation of the workers' and soldiers' councils,

-- formation of a proletarian red guard,

-- the immediate call for a world workers'congress in Germany in order to sharply and clearly stress the socialist and international character of the revolution. The international, the world r evolution of the proletariat is the sole anchor-point of the future of the German revolution" (‘The Beginning', 18.11.1918, R. Luxemburg, Selected Works, vol. 4, East-German Edition, p. 398).

Everywhere the workers were in the centre of the struggles. The workers came together in workers' and soldiers' councils in almost every big city. The trade unions, which during the war showed themselves to be the best bulwark of capital, lost influence during this initial phase. As Lenin had pointed out, the workers' and soldiers' councils proved themselves to be the finally discovered form for the organization of the workers' revolution. The workers came together in demonstrations in order to close their ranks as one class, in order to show their true force in society. Countless demos took place in Nov-Dec. in most big German cities. They were the point of unification of the working class beyond all factory and district limits. That's why the communists emphasized them so much in their agitation: "In times of revolutionary crisis, the masses belong as a matter of course out on the streets. They are the sole haven, the sole security of the revolution ... Their very presence, their contact with each other is a menace and a warning against all open and hidden enemies of the revolution" (‘Unaccomplished duties', R. Luxemburg, Jan. 8, 1919, Vol. 4, p , 524).

Just like in Russia the workers held meetings in the factories where resolutions were passed, delegations appointed, and measures taken against the state institutions.

The forms of struggle, which in the decadence of capitalism were to become the typical weapons of the proletariat, were applied: wildcat strikes, the formation of workers' and soldiers' councils as unitary organs of the class, mass demonstrations bringing together all workers, regardless of their profession, whether or not they were employed, the self-initiative of the workers themselves. As the workers' councils themselves and the revolutionaries at their head had proclaimed in Russia, the perspective of this movement consisted at once in the immediate extension of the revolution and the construction of a communist society.

" ... the moment of the final reckoning with capitalist class domination has come. But this great task cannot be fulfilled by the German proletariat alone. It can only struggle and win if it calls for the solidarity of the proletarians of the entire world" (‘To the Proletarians of All Countries', Nov.25, 1918, Spartakusbund).

The workers had massacred each other as cannon fodder in favor of each national capital in the imperialist war. The working class in Europe was divided through this nationalist poison. Particularly in the ‘victorious' countries like France, the bourgeoisie was able to use this ‘victory' to keep chauvinism and nationalism alive in the working class. The Spartakists, taking into consideration this weakness of the international proletariat, and convinced as they were of the necessity of the extension of the revolution, thus proclaimed:

"Remember. Your victorious capitalists are prepared to bloodily suppress our revolution which they fear as much as their own, You yourselves have not become any freer through ‘victory', you have become only all the more enslaved. Should your ruling classes succeed in strangling the proletarian revolution in Germany and in Russia, they will turn against you with doubled ferocity ...

Elect workers' and soldiers' councils everywhere in order to seize political power and to establish peace together with us ..." (ibid.).

The working class in Russia succeeded in toppling the bourgeois government after months of the polarization of power between the soviets and the Provisional Government, in order to seize power itself through the soviets. The Provisional Government could be brought down without much bloodshed. The workers' and soldiers' councils were able to rapidly exercise a real control over the country. It was only some time after the successful taking of power through the workers' and soldiers' councils that the bourgeoisie could begin an effective counter-offensive which threw the country into a civil war. This in turn drained the blood of the workers and peasants and eventually resulted in depriving them of any real power.

Although the movement in Germany was carried by the working class, which put forward the same perspectives as the struggles of the workers in Russia, the workers in Germany did not succeed in bringing down the capitalist class. The bourgeoisie torpedoed the power of the workers' and soldiers' councils from the very beginning. It never allowed for the formation of a new centre of the rule of the workers. It provoked premature military confrontations at a moment when the working class was not yet ripe for the insurrection. It immediately sought armed confrontation and inflicted devastating blows against the workers on a military terrain after having politically prepared this terrain. The most important aspect of this was the political disarming and then the political destruction of the Berlin workers' and soldiers' councils, which survived in name only (and whose very name was employed by capital against the revolution).

The social democrats' grip on the councils, the transformation of the latter into organs controlled by the bourgeois state, had the effect of destroying the councils from within. From being proletarian organs for the class organization of the proletariat and the destruction of the bourgeois state, they became a cover for the social democratic state before being definitively suppressed by the setting up of the National Assembly. Strengthened by its control over the councils, social democracy could organize the provocation of 1919 in Berlin to decapitate the proletarian movement and the Spartakist party.

The ascent of the movement in Nov./Dec. was broken in the first months of 1919. With the help of the Freikorps, a counter-revolutionary military force set up in the wake of the dissolution of the regular army at the end of the war with the aid of the SPD government, the bourgeoisie succeeded in massacring the workers in Berlin in January, in Bremen in February, in March in Central Germany and on the Ruhr, in April/May in Munich; one after the other, town by town, region by region, in one packet after another, crushing the backbone of the movement.

Although this did not put an end to the combativity of the working class, which kept, returning to the path of struggle up until 1923 (from the rising against the Kapp-Putsch in 1920 up until the rising in Central Germany and in Hamburg in 1923), in fact the movement was in retreat from the first months of 1919 on.

The origins of the defeat at the heart of the revolutionary wave

Just as with the failure of the previous most important workers' insurrections, 1848, 1871, 1905, the defeat of the 1917-23 revolutionary wave was not simply the result of the mistakes or even the absence of a revolutionary vanguard. In the same way, the defeat of the working class in Germany cannot simply be explained through the weak influence of the Communist Party. The relatively weak influence of the KPD reflected in its turn a deeply rooted weakness of the working class itself: the difficulty in understanding the fundamental change in the communist perspective brought about by the beginning of a new historic period, that of the decadence and decomposition of the capitalist mode of production.

It's true that the delay in the formation of revolutionary fractions in Germany before the war was to hold back the communist minority's capacity to deal with the revolutionary situation at the end of the war. The Communist Party was formed too late and too hastily under the pressure of the November revolution, without a long tradition of struggles and of combat against the bourgeoisie and the bourgeois fractions in social democracy, whose counter-revolutionary policies were clearly revealed in 1914.

However, what also has to be understood is that the war was not the best condition for the victorious outcome of the revolution.

Indeed, although both the Paris Commune and the mass strike of 1905 in Russia broke out at moments when war was taking place, the marxist movement had generally expected that the revolution would be triggered off, not in reaction to war, but as the final consequence of the proletariat's resistance to the economic crisis.

The rapid fall of capitalism into the bloodbath of First World War made it incomparably more difficult for the working class to develop a full consciousness about the real gravity and significance of this war. Since the workers had witnessed above all the bestial slaughter of the war, they were conscious mainly of the consequences of this war, without yet being aware of the other consequences of capitalist decadence.

This fact already led Luxemburg to draw the following conclusion:

"Departing from the basis of historical development, one cannot expect that a Germany which has presented the terrible picture of August 4 (1914) and the four years which followed could suddenly on Nov. 9 1918 experience a magnificent class conscious revolution, fully aware of its goals. What we have lived through on Nov. 9 1918 was three quarters more a collapse of the existing imperialism than the victory of a new principle. The moment had quite simply come at which this imperialism, like a giant with feet of clay, rotten from within, just had to collapse. What followed that was a more or less chaotic, unplanned, not highly conscious movement, in which the sole link and the remaining saving principle was summarized only in the slogan: formation of workers' and soldiers' councils" (Founding Congress of the KPD, 1918/1919, Collected Works, Volume 4, page. 497).

Although capitalism at that time had entered its decadent phase, this did not automatically and mechanically lead the working class to understand all the implications of the change of the period. The working class still suffered from the weight of reformism and was not able to draw all the lessons of this new epoch as quickly as the events themselves evolved.

This is why the illusion of a return to the prosperity of the 19th century was reinforced the moment the bourgeoisie conceded the demand for peace.

(To be continued)

Dino, Summer 1988

History of the workers' movement:

Decantation of the PPM and the Oscillations of the IBRP

- 3718 reads

IR 55, 4th Quarter, 1988

If we were to limit ourselves to a superficial examination of the state of the international political milieu, we could easily get depressed. Existing groups have split (A Contre Courant from the GCI, the Groppo Leninista Internazionalista from the OCI), are degenerating (Daad an Gedachte has capitulated to democratic frontism through support for the anti-apartheid front in South Africa, the EFICC has more and more put into discussion the programmatic bases of the ICC from which it emerged), or are losing their way (Communisme ou Civilisation has discredited itself by proposing in a completely unserious way to put out ‘communist journals’ with anyone who cares to listen to it; Comunismo, the former Alptraum Collective, has overnight decided that it no longer agrees with the concept of decadence, upon which all its positions were based). Or, more simply, they have just disappeared (self-dissolution of Wildcat, gradual disappearance through self-dissolution into the void of the numerous fragments which survived the explosion of Programme Communiste).

It is in fact on the basis of the impressions received from such an examination that there has developed in the milieu an atmosphere of depression and pessimism, leading some of the veterans of 68 of proclaim that the time has come for “self-critical balance sheets”. [1] And these balance sheets nearly all go in the same direction: despite the crisis, despite some important struggles by the working class, the influence and numerical importance of the revolutionaries have not grown, while at the same time the threat of war is still there... Thus everything is lost, or virtually lost.

In the first part of this article, we aim to show how this attitude of ‘retreat’:

-- does not in reality correspond to the state of the proletarian milieu

-- serves only to provide an ideological cover for the incapacity of a good part of the milieu to assume its responsibilities vis-a-vis the necessities of the class struggle.

In the context of this confusion, the responsibility that weighs on the shoulders of the two poles of regroupment, the ICC and the IBRP, is all the greater, since they are called upon to build a rampart against this insidious wave of distrust and desertion. In the second part of the article we will show how, because of its congenital incapacity to confront and resolve its internal contradictions, the IBRP is finding it more and more difficult to carry out this task and to provide an orientation for the debates within the milieu as a whole.

DEFEATISM AGAINST REVOLUTIONARY MILITANTISM

Although you can find signs of an attitude of distrust in the possibility of revolutionaries playing a role in the class struggle among nearly all the groups, their clearest expressions can obviously be seen in these groups who make distrust about the intervention of revolutionaries their sole reason for existence. The most exemplary case is without doubt that of the External Fraction of the ICC (EFICC), whose militants deserted the ICC in an irresponsible manner, under the pretext that it had so degenerated that it was no longer possible to struggle within it to prevent it throwing its original platform onto the scrap-heap. The falsity of this assertion is obvious today: three years later, the ICC has more and more strengthened its defence of its platform, whereas it’s the EFICC which is more and more discovering its ‘limits’. In reality, the divergence was on the analysis of the dynamic of the class struggle and the tendency for these comrades to arbitrarily give pride of place to internal debate above militant intervention in the class struggle. The EFICC denied this with virtuous indignation for three years, but now, given the pessimistic ambience reigning in the milieu, it has plucked up its courage and put its cards on the table. In issue no. 9 of International Perspective, we discover that “at the basis of the degeneration” of the ICC, there is the stagnation and degeneration of the whole milieu, and that, far from strengthening itself, it is today far weaker and more divided by sectarianism that it ever was in the 70s”. Consequently, we must have the courage to recognise that “in this period, theoretical elaboration (of which clarity in intervention is an integral part) is a much higher priority than organisation building... Therefore political clarification is our main task today.”

So finally we have a theorisation of what for three years was the EFICC’s practice of non-intervention in the class struggle. Naturally, such a regression, such an abandonment of militant commitment can only be greeted with enthusiasm by that part of the milieu which has always based its existence on a rejection of this militant responsibility in the confrontations of the workers’ struggle. Communisme ou Civilisation has already rejoiced in the steps the EFICC has taken in this direction: “next to the theoretical desert of the ICC, the EFICC’s prose can be compared to an oasis” (Communisme ou Civilisation. 22, May 87).

But it’s another sect which makes the struggle against the ICC its sole reason for existing, the Communist Bulletin Group (CBG), which has shown the greatest enthusiasm. This group (which put itself outside the proletarian political camp with its support for the gangsterist actions of the adventurer Chenier against the ICC in 1981) has rushed to declare itself “entirely in agreement” with the conclusions of the EFICC, or rather, and here it’s quite right, has underlined that the EFICC is now reaching the same exalted level of struggle against any militant, centralised communist activity that the CBG triumphantly attained at the beginning of the ‘80s. It is thus seizing a favourable moment for its defeatist propaganda that has finally ‘found an echo’. No. 13 of its bulletin immediately put at the disposal of those who have doubts and hesitations a ‘coherent’; theorisation of defeatism which is based on the following points:

1) “As the EFICC points out our fundamental assumption that the deepening economic crisis would find its counterpart in deepening class struggle and a corresponding growth in the size and influence of revolutionary fractions has been confounded by reality”.

2) The milieu developed positively from 68 to 75: “at that point the revolutionary movement had reached a plateau”. After that, “there has been no growth in numbers and influence... In many ways the milieu is weaker now than it was a decade ago.”

3) “Divisions which were emergent in the 1970s have now hardened into dogmatic barriers of such strength that it is difficult to see how they can be overcome. Certainly it does not seem at all to be correct to believe that greater militancy in the working class will draw revolutionaries together”.

The conclusions are predictable: we have to stop the effort to build a centralised organisation whose task is to intervene in the class struggle; we have to dedicate ourselves to a work of study and of ‘open’ debate, in which will participate, at a level of formal equality, militant organisations, individuals, and circles who have nothing better to do. This ‘fraternal’ academic debate will of course pose the bases for the future party of the proletariat.

Such theorisations can’t fail to find an echo here and there. The former Alptraum Communist Collective in Mexico, now Comunismo, would certainly be in agreement, since it has now resolved its long hesitations about intervening in the class struggle by denying the necessity for intervention and the reality of the class struggle today (both inventions of the ICC...) and by deciding that its sole task is the publication of a theoretical journal (with Communisme ou Civilisation, funnily enough), while awaiting the all-powerful party of tomorrow.

The comical side of this tendency towards strategic retreat is that it conglomerates into a single front both the partisans of the one and only, iron-hard, monolithic party (Communisme ou Civilisation, Comunismo), and the admirers of an ‘open’, democratic party, in which everyone is free to say and do whatever they please (EFICC, CBG). The only two things that unite this disparate front are:

-- the hope of living long enough to witness this ‘collapse’ of the ICC which they’ve been waiting for so long but which never comes;

-- the absolute conviction that in the present conditions of the class struggle, the intervention of revolutionaries plays no real role.

The two things are obviously interconnected: the ICC is today the main pole of regroupment in the international proletarian milieu, and the most determined defender of the role of revolutionaries in the class struggle. This means that any attempt to put this role into question is obliged to settle accounts with the ICC. But this also means that the ICC is ready to settle accounts with any effort in this direction, by going through the arguments one by one. This is what we have done and what we intend to continue doing.

THE DIFFICULT ADVANCES OF THE PROLETARIAN POLITICAL MILIEU

You can find a more detailed response to the attempts to falsify the last 20 years of the history of the workers’ movement in the series of articles ‘The evolution of the proletarian political milieu after 68’ (IR 53 and 54), and we refer readers to these articles. In the present article, we will therefore limit ourselves to replying to the various basic affirmations contained in the CBG’s theorisations about the milieu and shared by a good part of the milieu itself.

Let’s begin with the central observation, according to which the revolutionary movement grew numerically and politically from 68 to 75, then stagnated numerically and regressed politically. In order to present things in this way, it is necessary to falsify shamelessly the real dynamic of events. It is absolutely true that the years 68-75 saw a whole process of decantation and of politicisation around the French group Revolution Internationale, which led to an international regroupment in the ICC, and to one limited in Britain in the CWO. But it’s also true that the years 72-75 saw the outbreak of the ‘modernist’ mode, with the ensuing abandonment of marxism by an enormous number of militants who, in those years, had only just broken with the extra-parliamentary groups to discover the positions of the communist left. If the CBG thinks it can stir us by talking of the ‘good old days’ where it seemed that everything was moving towards the positions of the communist left, then it’s come to the wrong address. The fact that thousands of individuals, who the day before had sworn by Trotsky’s Transitional Programme or Mao’s Bloc of Four Classes, should suddenly start quoting Pannekoek and Bordiga, was not a strength but a weakness, and above all a very serious danger for the revolutionary movement.

If we were able to regroup a small part of these comrades in a homogeneous political organisation, it is because we understood and said all that at the time and not just today:

“The international reappearance of a communist current is laborious, uncertain, tentative, and it is late in relation to the resurgence of the class struggle. What’s more, it is often due to the conjuncture of elements coming together more by chance than by an historical determination. But at the same time, the long purgatory that the existing groups have gone through and the crises provoked within them by the increasingly opportunist, recruiting-sergeant, boot-licking course followed by the radical currents coming from the counter-revolution (Trotskyism mainly) will result and has already resulted in our ideas suddenly coming into fashion. Numerical weakness will no longer be the heavy burden our current bears; the main danger will be that of being ‘too many’, of being diluted into a mass of elements who have not yet fully understood our positions and their implications.” (Bulletin d’Etude et de Discussion de Revolution Internationale, no. 4, Jan 74).

We were able to constitute what is today the main pole of regroupment precisely because we did not lose our heads over the fact that the positions of the communist left suddenly came into fashion, but rigorously differentiated ourselves from all those who rejected political demarcations around clear positions. It was not by chance that, already in 1975, the constitution of the ICC was greeted by a unanimous choir of accusations about ‘monolithism’, ‘sectarianism’, ‘closing off from other groups’, ‘paranoiac isolation’, ‘thinking that we were the only depositories of truth’, etc from a whole crowd of circles and individuals who, one year later, fortunately dissolved themselves into the void.

The years between 1975 and 1980, far from showing that there was a new stagnation of the revolutionary milieu, were characterised by the fact that they saw an evolution in the majority of the groups in the milieu, whereas many of them had indeed stagnated during the phase of confrontation and regroupment in the years 1968-75. The whole milieu subdivided into three main tendencies:

a) isolation in passivity and academicism (the vestiges of the historical councilist current);

b) isolation in activism devoid of principles (Programme Comuniste, which throughout the 70s had been the main communist organisation);

c) the break with isolation through confrontation and political debate (the international conferences of the groups of the communist left, animated by Battaglia Comunista and the ICC).

The first balance sheet that we can draw is that the conferences were the first dynamic element capable of polarising the WHOLE milieu; in fact, even the groups who did not participate (Spartacusbond, Programme Comuniste, etc.) felt obliged to justify publicly their refusal. The second balance sheet is that, beyond the immediate results, which certainly did exist (rapprochement between Battaglia and the CWO, fusion of the NCI and Il Leninista, birth of a section of the ICC in Sweden), the conferences remain an acquisition for the future:

“The bulletins published in three languages after each conference and containing the various written contributions and the accounts of all the discussions have remained an indispensable reference for all the elements or groups which have since come to revolutionary positions.” (‘Evolution of the revolutionary milieu since 68’, IR 54.

The ideologues of the retreat are careful not to talk about any of this: the fact that the positions of the communist left are now present in India and are being defended in Latin America is probably for them nothing but an ‘exotic curiosity’. But let’s move on to another point, to the idea that the influence of the communist minority has not grown in parallel with the crisis and the class struggle. Naturally, if by influence one understands the number of workers directly organised in revolutionary organisations, then it’s clear that it hasn’t grown much. But in the decadent phase of capitalism, the influence of the revolutionary minority is manifested in a very different way; it is manifested in the capacity to play a role of political leadership within the significant struggles of the class. It’s on the basis of the strengthening of this capacity to push the struggles forward, to politically influence the most active, most militant workers that the conditions will develop for the integration of a growing number of worker militants into the revolutionary organisations.

If we consider things from this point of view, the marxist point of view, it’s a simple fact that in the last few years the organisations which, like the ICC, have maintained a constant pressure at the level of intervention in the class struggle, have been for the FIRST TIME capable of influencing minority sectors of the class in the course of wide-scale struggles, as was the case with the French railway workers or the Italian teachers. This never happened and COULD NOT have happened in the 70s, because the conditions for it did not yet exist [2]. Today, THIS IS BEGINNING TO BE POSSIBLE, thanks to the maturation of the crisis, of the class struggle AND of those communist organisations who have managed to come through the process of selection which has taken place over these last few years.

Finally, let’s deal with the third dolorous proposition: the notion that today the milieu is more divided and sectarian than in the 70s and that the class struggle itself cannot push the revolutionaries to discuss among themselves.

We have already seen that this pessimistic vision does not take into account the fact that the majority of the revolutionary milieu in the years 68-75 stayed rigorously outside any dynamic towards contact and discussion, whereas today, the two main poles of regroupment which exist at an international level – the ICC and the IBRP – both defend, even though in different terms, the necessity for a debate.

It’s no accident that the new groups that are now appearing, in particular on the peripheries of capitalism, tend immediately to refer themselves to the debates between these two poles. Today, however displeasing it may be to those who believe that debate between revolutionaries is a type of supermarket which, in order to be rich and satisfying, has to offer a choice between thousands of diverse products, this selection process is not an ‘impoverishment’ but a step forward. This polarisation allows the new elements to situate themselves clearly with regard to the FUNDAMENTAL political divergences that exist between the main currents of the revolutionary movement, instead of getting lost in the thousand secondary refinements of this or that sect. It’s obvious that this is bad news for the sects, and explains why they are screaming about the ‘strengthening of divisions’; what makes them cry so loud is simply the acceleration of history, i.e. of the crisis and the class struggle, which is continually pushing towards the decantation of the revolutionary camp. It is this acceleration that has compelled the comrades of Wildcat to recognise that they had reached a dead-end and to dissolve a group that was nothing but a source of confusion. It is this acceleration that has made possible the relatively rapid process through which a milieu of Mexican militants has managed to break with the counter-revolution, giving rise to a new communist group, the Grupo Proletario Internacionalista. It was the obligation to take account of this acceleration, which has given rise to this MILITANT communist group, that finally pushed the already existing group in Mexico, the Alptraum Collective, to resolve its six years of hesitations about militant commitment, by opting for the suicide of academic regression. Even a negative choice of this type is in any case preferable to ambiguity: from now on, the Mexican elements in search of a class coherence will be faced with a clear choice: either a commitment to revolutionary militancy with the GPI, or the hobby of discussions with no implications in Comunismo, ex-Alptraum (if in any case the latter survives at all).

The question of militant intervention in the class struggle is therefore becoming a factor of clarification and selection. But what is most important is that, contrary to the sombre prophecies of the birds of ill omen, intervention is also beginning to be a factor of INTERACTION among revolutionaries.

The progressive emergence of a definitely class conscious minority, which showed itself openly in the school workers’ struggle in Italy, has also and above all been the result of an ORGANISED and JOINT work on the part of the internationalist militants who participated in the struggle (militants of the ICC, of Battaglia, and of the Bordigist group Il Partito Comunista).

This is only a small example, but it is nevertheless the FIRST EXAMPLE of a collaboration in the struggle which the deepening of the class movement will no doubt make much more frequent.

The consequences for the whole milieu are obvious: the debates – often rather abstract – of the past will tend to deepen thanks to the confrontation of positions with the reality of the class struggle. Very good for the debate, very bad for the parasitic groups who have little or nothing to do with the class struggle.

THE IBRP AND THE CLASS STRUGGLE: A FEW CONTRADICTIONS TOO MANY

In this second part of the article, we will examine the difficulties encountered by the IBRP (the biggest pole of international regroupment after the ICC) in mounting an adequate resistance to the wave of defeatism that is flowing through the revolutionary milieu.

The first difficulty comes from the fact that the IBRP is itself the victim of a pessimistic vision of the present movement of the class struggle, and so finds itself poorly placed to resist the defeatist propaganda. In the previous issue of the International Review we looked more specifically at the question of the underestimation of the present class struggle by the milieu and by the IBRP in particular, while in nos. 50 and 51 we dealt with the IBRP’s incomprehension’s about the historic course and the union question. In this article, we will return specifically to a problem that we have underlined more than once: the growing contradictions in the positions taken up by the IBRP on all the questions of the hour.

For reasons of space, we will limit ourselves to one example that seems to us to be particularly significant. We want to talk about the central question, i.e. the level of the class struggle and whether or not there is a possibility for revolutionaries to play a role within it. In the now famous letter of June 87 from the IBRP to the Alptraum Collective, amply criticised by us in the previous issue of the IR, the struggle of the school workers in Italy, which for months was organised through the COBAS, was put at the same level as that of professionals such as pilots and magistrates, and thus left to its own devises more or less until the summer. In autumn 87 the CWO held its annual general meeting, which made a theory about the profound coma of the British proletariat and the Thatcher nightmare; and in its perspectives, given that there was a “period of social calm”, affirmed that “we have more need for, and more time for, a shift towards theoretical work: (Workers’ Voice no. 39. Feb-March 88).

In February 88 the annual assembly of Battaglia Comunista affirmed that:

“With the affair of the COBAS a new and interesting phase of the class struggle has begun in Italy, one which offers our organisation the possibility of arousing an interest from within the movement which is certainly greater than in the past.... The comrades of the CWO who intervened at the meeting referred to the recent developments in the class struggle in Britain: there were now strikes where there had been none before, and even solidarity strikes between workers of different sectors. These struggles also confirm the beginning of a period marked by the accentuation of class conflicts.” (from the report published in Bataglia Comunista no. 3, March 88).

As we can see, both the particular analysis of the situation in Italy and Britain, and the consequences drawn from it on a general level (“the beginning of a period marked by the accentuation of class conflicts”) are in total contradiction (fortunately) with the preceding analyses. What is striking is that no. 39 of Workers’ Voice, which came out AFTER the wave of struggles in Britain, still contained, WITHOUT A WORD OF CRITICISM, the perspectives of the annual meeting of the CWO which were founded on the "demoralisation and passivity" of the British and world proletariat. What then, in Feb-March 88, was the position of the comrades of the CWO? The optimistic one published in Battaglia, or the pessimistic one published in Workers’ Voice?

The situation seems to get clearer in WV 40 of April-May 88, where, in the introduction to the article on May 68 (“the first generalised awakening of the class struggle after the years of post-war reconstruction”), it is nearly stated that “the last months have seen stirrings in the UK, Germany and elsewhere that foretell a renewal of the social conflict”. But any hope of having finally understood the position of these comrades is short-lived. A few weeks later, the CWO sends a letter to the Communist Bulletin Group on the same questions:

“...broadly speaking we have rejected what we feel is our last baggage from the ICC, i.e. the idea that May 68 opened up a new period, the end of the counter-revolution and the beginning of a new revolutionary period... what we are now definite about is that this is NOT a ‘pre-revolutionary period’, but a continuation of the capitalist domination that has reigned, to be only fitfully contested, since the end of the posit-WW1 revolutionary wave. There are, as I’m sure you will agree, many consequences of this... The vanguard is doing badly because this is not a period of ‘pre-revolution’ but a period of (increasing) capitalist domination” (letter published in no. 13 of the Communist Bulletin).

This letter not only totally negates what was written in WV 40, which was being distributed at the same time, but also represents an UNCONDTIONAL CAPITULATION to the defeatist pressure coming from the parasitic elements in or around the milieu, and from the CBG in particular... Let us note that the CWO took the trouble to say that it had no objection to the publication of this letter. It was thus with great concern that we opened WV 41 which was to contain an article on the 20 years since 68 as promised in the letter to the CBG. But here was another volte-face; the article on 68 was not there, but there was on the other hand an article on the revolutionary milieu, which says:

“However, the May events in France in 1968 were the first of many workers’ strikes which signalled the end of the post-war capitalist boom... This gave birth to the present proletarian political camp... in recent years there has been a growth of communist groups in the capitalist periphery.”

This is exactly the opposite of what was written in the letter being published at the same moment in the Bulletin.

The least one can say is that on this question there are at least three different positions in the IBRP:

-- CWO no. 1: yesterday, end of the counter-revolution in 68, today, revival of struggles;

-- CWO no. 2: yesterday, no change in 68, today, growing domination of capital;

-- BC no. 3: yesterday no change in 68, today “something is beginning to move, even if it’s not yet sufficient” (Prometeo no. 11, Dec 87).

We thus have three positions or perhaps four, since at the public meeting held by the ICC in Milan in June 88, a comrade of BC intervened to point out that “there are less of us today than there were in 68”.