September 2015

- 1212 reads

Max Raphael and a Marxist perspective on art (Part 1)

- 3809 reads

By starting a new heading of ‘Readers’ Contributions’ on our website, and occasionally in our paper, we hope to encourage our readers and sympathisers to write texts and articles which can go into greater depth than is possible in our discussion forum, and so stimulate a longer term reflection. These articles, while being broadly based on proletarian politics, need not fully represent the positions of the ICC, or may deal with issues on which the ICC does not have a collective view. The question of art is clearly such an issue, and we welcome Boxer’s effort to deepen our understanding of the marxist approach to humanity’s creative productions.

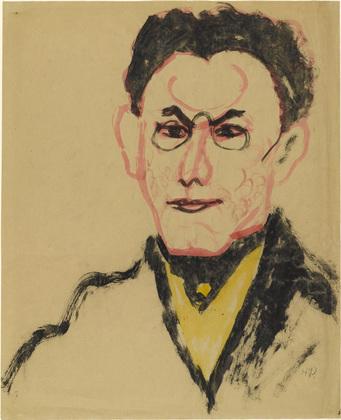

The main purpose of this article is to bring the work of Max Raphael into the field of contemporary marxist attention and discussion where it belongs. The bourgeoisie calls many of its intellectuals “marxist”, which not only serves to give them a sheen of credibility but usually helps to debase genuine marxist contributions. Many learned individuals have important things to say around the various ideological spheres that have grown up around society and this is to be expected. But unlike the bourgeois “marxists” who pronounce on the ideologies of the ruling class, the views of Max Raphael are very clear on the necessity of the revolutionary overthrow of a corrupt and destructive capitalism by independent working class action, and this fact alone leads us to express an interest in trying to understand his works. Raphael wrote dozens of books and many more papers on art, mostly in French and German with a few in English. He said that if one wanted to understand his views on art then all of them should be read. We can’t do that or even approach it, but we can draw out some elements in order to give us a deeper perspective on art within a framework of the workers’ movement.

Art is a difficult question for marxists and this is reflected in the lack of positions from the political sphere in general, often in the face of much more pressing necessities. It is difficult and complex but it is an important part of society and elements of it have been covered by marxism, including Trotsky, by the ICC drawing out some salient points in its “Communism” series and in the excellent text by MH on this website, “Notes towards a history of art in ascendant and decadent capitalism”[1] which also refers to these previous contributions. In fact a short quote from Trotsky’s “Art and Politics in our epoch”[2], mentioned in MH’s text, indicates how Raphael approaches the question of art. The framework of the quote from Trotsky, quite correctly, is the drive towards destruction by decaying capitalism of everything that’s been built up within it, including art; an art, according to Trotsky, which will be destroyed “as Grecian art rotted beneath the ruins of a culture based on slavery”. Now while the content of the quote is apt in the framework of decay, it’s obviously not the actual case that Grecian art rotted beneath the ruins of Greek society. On the contrary, it persisted with strength, became incorporated into artistic developments and was revived again and again and still fascinates us today. Trotsky himself points to the complexity of the issue in his 1923 Communist Policy Towards Art: “...art must make its own way by its own means”. This begins to point to the nub of the problem: what is the relationship of this ideological sphere which is art to the economic substructure of society[3]? This is the question that Max Raphael addresses over all his works; it is his mission to try to address it in all its glory. In his text MH clearly shows the relationship between an ascendant capitalism that used art to decorate and promote the consolidation of its dictatorship, and its decay which turned what art there was mostly into trash.

Marx, in a profound quote below, puts the whole question of the relation of the ideology (art) to the economic and political substructure (the productive basis) to the test and Raphael takes up the problem posed from here applying the marxist method to it with some rigour.

Who was Max Raphael?

Max Raphael was born in Germany in 1889 and studied philosophy and art at university. He also studied some of the writings of the workers’ movement including Marx and Engels. He was conscripted into the German army for the First World War and there are reports that he deserted in 1917. He led an austere and difficult life, suffered racial and political persecution and held no official academic position in the art world from whose cultural hierarchies he was completely isolated. In the 1920’s he was kicked out of Berlin’s Volkshochule after the directorate heard that his unofficial lectures on art included dialectical materialism. Despite, or rather because of, the unparalleled contribution that he was making to a critique of art and society he, as one later art commentator described, “scourged” the art institutions of both the democratic west and The Palace of Soviets. All sides treated him with suspicion and it was just a small group of friends and unofficial pupils that kept his work alive. He fled persecution in Germany in the 30’s for France where he met Picasso, Matisse and Rodin in Paris, but he never owned a work of art. He made visits to Sicily and Greece, where he studied Doric architecture and visited many art galleries, which he described as “mausoleums”. He was interned twice in France in camps for Jews and dissidents and after the second time fled to America where, living on his wife’s wages as a cleaner in New York City, he committed suicide in 1952. Some of his statements could be taken as support for anti-fascism but he was pursued by the Nazis in Paris and his critique of Picasso’s Guernica, an artist whom he called “the greatest of our time”, by no means follow the anti-fascist narrative. His study of Guernica, when it was on loan to New York, took days and he literally studied it from every angle. He was daring and thorough in his analyses and his starting point was both the general historical conditions, what was the weight of their application to the art produced and, from another direction within the ideology, what is the intrinsic nature of the artist, the effect of society on him, his materials and the work of art itself?[4]. Going from the single artist, the weight of society on the individual and the original “idea” for a work, how do you also factor in the developing altered state of consciousness that grips the artist? On the ferment within the artist, Raphael, in his The Demands of Art, quotes Paul Cezanne, an artist who pretty much had his feet on the ground, on his state of mind when painting: “I am in such a state of cerebral agitation, in an agitation so great, that at one point I was afraid it would engulf my reason” (Letter to Emile Barnard while painting the landscape of Mont Sainte-Victoire. Cezanne, incidentally, despised capitalism and talked of the future emergence of “a truly revolutionary art”. How do you square all this? How do you take all these factors, subjective and objective, into account? The answers to these questions lie in the complexity of their dialectical relations. Art won’t change the world and Raphael is clear that this task belongs to other forces. But the struggle to understand art is for him part of “the struggle for a social order in which everyone will have the fullest opportunity to develop their creative capacities”[5]. At the end of the section on Picasso, in his book Proudhon, Marx, Picasso[6], Raphael talks about the inability of the modern artist to be able to express any revolutionary content in an “... epoch torn apart by contradictions” -and how could they when stuck within a bourgeois framework? Raphael is referring to Picasso in this next quote from the same work but his words here have a much wider resonance: “Thus, what has not yet been born is in a sense already outmoded, for the motive force of history is already on the other side of the barricade. The mere fact that there is a proletariat conscious of its class and struggling for it – however little this fact has entered the artist’s consciousness and sphere of experience – already today deeply influences the subconscious of the intellectual worker. The need for a new, integral work of art adapted to a new social order, makes itself felt in all his creations. But all the convulsions and all the individual sufferings of a bourgeois genius will be inadequate to meet this need”.

The “eternal charm” of Greek art

With Trotsky’s quotes above, which Raphael is unaware of as far as I can see, there’s a certain ambiguity towards art: that Greek art is “buried” but that art must also “find its own way”, the latter implying some sort of independent existence. This, I think, is representative of the fitful approach that, by necessity, marxism has taken towards the development of art. Engels recognised the problem of the question of the relations of the superstructure, art in this case, to the economic core. To make the issue more complex – and ultimately more rewarding – then the superstructures, the ideologies of society do not have the same relationship to the base but, further, have complex relationships between themselves. Raphael quotes Engels in this respect: “... In the first instance we all laid, and were bound to lay, the main emphasis on the derivation of political, juridical and other ideological notions, and of actions arising through the medium of these notions, from economic facts. But at the same time we have on account of the content neglected the formal side the manner in which these notions, etc., come about”[7]. Engels regularly returns to this question in the 1890’s in his correspondence with Paul Ernst, Joseph Bloch, W. Borgius and Conrad Schmidt – all quoted by Raphael in the section on Marx in Proudhon, Marx, Picasso. For Engels the relationship of art to the political economy is one that cannot be charted easily and mechanically. There is a relationship but it doesn’t take a parallel course: it diverges, moves in zigzags, can be far apart or closer but, generally, over the course of time the relationship exerts itself. The nature of this relationship, the relationship between subject and form, matter and spirit, the levels that they reach in the totality of their relations, their interdependence or not, is the question that Max Raphael deals with in some detail.

He quotes Marx in respect of the above: “In order to examine the connection between spiritual production and material production it is above all necessary to grasp the latter itself not as a general category but in its definite historical form. Thus for example different kinds of spiritual production correspond to the capitalist mode of production and to the mode of production of the Middle Ages. If material production itself is not conceived in its specifically historical form, it is impossible to understand what is specific in the spiritual production corresponding to it and the reciprocal relationship of one on the other. Otherwise one cannot get beyond inanities”[8].

From what I’ve read of Raphael he was greatly motivated by the statement from Marx in his introduction in Grundrisse where the problem is posed more clearly (in a sense): “But the difficulty lies not in understanding that Greek arts and epic are bound up with certain forms of social development. The difficulty is that they still afford us artistic pleasure and that in a certain respect they count as the norm and as an unattainable model.

A man cannot become a child again, or he becomes childish. But does he not find joy in a child’s naivety, and must he himself not strive to reproduce its truth at a higher stage? Does not the true character of each epoch come alive in the nature of its children? Why should not the historic childhood of humanity, its most beautiful unfolding, as a stage never to return, exercise an eternal charm? There are unruly children and precocious children. Many of the old peoples belong to this category. The Greeks were normal children. The charm of their art for us is not in contradiction to the underdeveloped stage of society on which it grew...”[9]. There’s a great deal in this quote but in relation to art this follows on from Marx’s statement a couple of paragraphs earlier in his introduction explaining that, in certain periods, the flowering of art is out of all kilter with the material foundation of society and its general development. “...certain periods of the highest development of art stand in no direct connection with the general development of society, nor with the material basis and skeletal structure of its organisation”. He further talks about the different elements in the domain of art itself and how they influence one another, and predates Raphael in saying that within this domain whatever hasn’t yet been born is already outmoded.

The negation of cause and effect by reciprocal action

There was very little motivation (and time) to move Marx and Engels in the direction of art but what they did say about the question takes us forward in leaps and bounds and particularly on the way we approach it. Idealist philosophy a la Proudhon is of no use here, relying as it does on its fundamental a priorism. In relation to the problem posed by Marx and the “eternal nature” of Greek art, founders of historical and dialectical materialism were not impelled to delve further into the question of art. Raphael writes in The Marxist Theory of Art: “Moreover, those who wanted to treat these problems empirically had no exact science available to help them. Aesthetics was unusable, consisting as it does of a mixture of metaphysical deductions and empirical findings which are determined by the deductive method rather than by objective laws; on the other hand, the history of art, to the extent that one may be said to have existed, was concerned with a host of external manifestations rather than with the phenomenon of art itself”. Raphael himself finds aesthetic values useful for art in general with its “normative values” and the “aesthetic values” of play (and sexuality) in relation to art.

the study of the mind, right up to today, remains crude and the line between subjective emotion and scientific method difficult to draw. You could say that art developed in a certain aloof, autonomous manner “away” from society – in fact in one of his letters Engels uses the term “the relative autonomy of art”. More than that, art also has certain relationships with other ideologies as well as relationships within the different domains of art itself. Again Raphael quotes Engels: “Political, legal, philosophical, religious, literary, artistic, etc., development is based on economic development. But all these react upon one another and also upon the economic basis. It is not that the economic situation is cause and solely active, whereas everything else is only passive effect. On the contrary, interaction takes place on the basis of economic necessity, which ultimately always exerts itself”[10].

The “eternal charm” of Greek art in Marx’s 1857 introduction to Grundrisse, is a long way from, a lot more complex than Trotsky’s idea of Greek art being interred under ruins. And it is from this passage of Marx that Max Raphael sees the most important tool for building up a marxist theory of art. This passage from Marx is no simple statement but the posing of a fundamental problem and from it Raphael attempts to show that dialectical materialism can provide the way for going forward in the face of all the apparent contradictions. For him a detailed analysis of the statement by Marx “... will show that dialectical materialism, providing it is applied correctly, supplies us with the means for successfully overcoming all such initial obstacles as arise from social and individual factors, and for going forward to a theory and sociology of art. This method also enables us to eliminate the almost inevitable drawbacks of the initial situation, namely the fact that art and the pseudo-scientific method for dealing with it serve as a metaphysical refuge for the reactionary bourgeoisie and, at the same time, afflict all superficial, and hence dogmatic, Marxists with a kind of anxiety neurosis”[11]. If an “eternal charm” exists, despite changed historical, social and economic conditions, then there must be an eternal source to it. So the task for marxism is to produce something of an accurate analysis of the spiritual process that connects historical conditions with “eternal charms”; that is, according to Raphael, “the values created by mankind transcending the limits of a given epoch”. The problem remains unsolved. Marx excluded religion from communism because it sets limits on the creative ability of mankind and diverts action away from class struggle by preaching class collaboration. But he certainly saw art as part of a new society, because while it could also have an opiate effect it could also be a powerful weapon. Art is a synthesis of nature (with history) and the human mind and in its expression it acquires a certain autonomy from both.

Following Marx and Engels, there’s no vulgar “art comes from the economy” from Raphael. For him there are three important questions posed by the quote from Marx above:

- Myth as an intermediary in the move from the economic substructure to the ideology of art;

- The lack of proportionality between economic and ideological development;

- The “eternal charm” of an artistic expression whose economic foundations disappeared ages ago.

Mythology is a force created by mankind in order to try to subdue, control and affect the forces of nature. This is especially true of Greek mythology where the myths were accepted by the same people with the same cultural background, from the same economic order expressing a single collective character of the beginnings of the unconscious process from which art arises. Marx also said that mythology was an intermediate historically determined link which disappears when mankind gains mastery over nature; and in the section on Marx in his book Raphael goes into great detail about mythology. Greek mythology was a generally understood product of a single people’s imagination and its symbolic power is a bridge to a generally shared understanding. The symbol, for Raphael in The Demands of Art, “...for all its visible finitude, points to the infinite: it is a sensory synthesis of the finite and the infinite and hence has a character of necessity. Allegory (such as used by Picasso in Guernica for example, B) is merely a metaphor for the gulf between the two and hence always arbitrary. It leads to dogma rather than a dialogue between the self and the world”. Because of its specifics here this could be expressed with Greek art and not with Egyptian art for example, because the latter’s mythology was produced and mediated by a priestly caste. Later on, according to Raphael, Christianity and Christian art tried to join the forces of natural, popular development and priestly organisation. There’s no doubt about the assimilation and use of barbarian (i.e., non-civilised) art by Christianity and expressions of Christian art.

All we’ve done here is taken a superficial view of Max Raphael’s analysis but they are nevertheless very important steps for beginning to develop a marxist view of art. I hope to return to these questions above, particularly the deeper elements of his book Proudhon, Marx, Picasso. But for now Marx saw Greek art as an expression of the “Historical childhood of humanity... its beautiful unfolding, as a stage never to return” expressing an “eternal charm”. How much more then does this apply to a much earlier “childhood” expression of art that Marx and Engels knew nothing about: Upper Palaeolithic cave art. We will look at this particular expression and Raphael’s analysis of it in the next part [2] of this series.

Boxer, 4.2.15

[3] An explanation of the word “ideology” is necessary here. Raphael uses the term in relation to the domain of art in the same way that Marx and Engels use the term: ideology, in this case the ideology of art, is a superstructural element coming from the economic base in the same way that science, law, politics, philosophy, etc., are ideologies possessing elements of their own laws and history, affecting spheres within themselves, other ideologies and, to some extent, the economic base in a dialectical process. For Raphael, there is, following Marx, a relative independence of these ideological expressions and Engels talks of the “relative independence and relative autonomy of art” whose relationship to the economic base is neither mechanical nor linear but one which does ultimately assert itself as one of dependence.

The origins of art are obscure and inaccessible but it is very likely that they lie very much in the basic productions of society: clothes, shelter, food, etc. Art is part of humanity’s spiritual production with its dialectical relationship to material production.

For Marx the problem raised in this case is the dependence of spiritual production upon material production and Raphael (in Proudhon and the Sociology of Art says that “(for) Marx ideologies reflect material production in the human mind, the more or less illusory character of this reflection being ultimately determined by the class struggle”. The essential question posed by Marx in Grundrisse, and the one that Raphael begins to address, is that if there is an “eternal nature” to Greek art then what is its essence given that the economic basis of that society has long since passed?

Ideology in the marxist sense equals superstructure . The Italian communist left sometimes referred to marxism, historical materialism, as “ideology”. But what’s distinct about the ‘ideology’ of marxism - so distinct as to make the term ideology inadequate to describe it - is that it is the theory of class which has no need to mystify reality, and thus has a unique capacity to approach the relationships between ideology, ideologies and the economic base; and this is the work undertaken by Raphael in relation to art.

[4] In his book The Demands of Art, Raphael spends some 50 pages and six plates analysing one painting by Cezanne.

[6] Proudhon, Marx, Picasso Three Studies in the Sociology of Art, first published in 1933 in Paris and in English by Humanities Press in the US and Lawrence and Wishart in England, 1980.

[7] Frederick Engels, “Letter to Franz Mehring (July 1983), Selected Corresponence.

[8] Karl Marx, Theories of Surplus Value, Part 1, Moscow, 1963, p. 285.

[9] Karl Marx, Grundrisse, Foundations of the Critique of Political Economy. Penguin Books, 1973, p. 111.

[10] Engels, “Letter to Borguis”, Selected Corresponence, pp 442-3.

[11] Max Raphael, Proudhon, Marx Picasso, p. 76.

General and theoretical questions:

- Culture [6]

- Pre-capitalist societies [7]

People:

- Max Raphael [8]

Rubric:

Migrants and refugees: the cruelty and hypocrisy of the ruling class

- 2366 reads

A few facts are enough to show the horror of the situation facing the migrants:

- On 27 August, in Austria near the Hungarian border, 71 bodies (including 8 women and 4 children) were discovered in an advanced state of decomposition, locked into a lorry abandoned by the roadway;

- A few days later, the body of a little boy of three, drowned at the same time as his mother and brother, was washed up on a beach at Bodrum in Turkey.

These were both cases of migrants from Syria fleeing the nightmare of four years of war. This phenomenon of refugees has now been globalised on an unprecedented, going well beyond the exoduses of the worst years of the 20th century.

Propaganda and solidarity

One thing about this is striking. The media are not trying to hide the unbearable horror of the situation. On the contrary, they are headlining it and are coming up with more and more shocking images, like that of the little boy on the beach. Why?

In fact, the bourgeoisie is exploiting, for the purpose of its propaganda, both the barbarism for which it is itself responsible, and the feelings of indignation it provokes, and the spontaneous expressions of solidarity between local working people and migrants which in the last few months has begun to develop in several parts of Europe. The propaganda is aimed at strangling at birth any possibility of independent thought and to instil nationalist ideology in a more insidious way. In the eyes of the ruling class, left to themselves, proletarians in Europe are acting in a curious and even irresponsible way: they are helping and supporting the migrants. Despite the permanent ideological bombardment, we find that very often when these proletarians are in direct contact with the refugees, they bring them what they need to survive - food, drink, blankets - and sometimes even take them in to their homes. We have seen such examples of solidarity in Lampedusa in Italy, Calais in France and a number of cities in Germany and Austria. When, after being hassled by the Hungarian state, train loads of refugees have arrived at the stations, the exhausted migrants have been welcomed by thousands of people offering them support and material aid. Austrian rail workers have worked extra hours to transport the refugees towards Germany. In Paris, thousands demonstrated on 5 September to protest against the treatment of the refugees. They raised slogans like “we are all children of migrants”.

Faced with such massive and international expressions of solidarity from the civil population, when the main concern of the state has been to intimidate the refugees and keep them under control, the ruling class has had to react. Almost everywhere the bourgeoisie has had to modify the anti-immigrant discourse of the last few years and adapt to the situation. In Germany, the turn-around of the bourgeoisie has helped it to strengthen the image of the country as a very advanced democracy, to exorcise the ghosts of the past in response to those of its rivals who never miss an occasion to refer to Germany’s dark history. What’s more, it’s the trauma of the Second World War which explains the sensitivity of the German proletariat to the question of refugees. The German authorities have had to suspend the Dublin agreement which calls for the deportation of asylum seekers. In the eyes of the world’s migrants, Angela Merkel has become the champion of Germany’s openness and a model of humanity. In Britain, David Cameron has had to modify his hard line stance, along with the worst right wing tabloids which up till now have been describing migrants as a threatening and sub-human horde. For the bourgeoisie, one of the key issues has been the need to hide the fact that there are two totally antagonistic logics at work here: capitalist exclusion and ‘every man for himself’ versus proletarian solidarity; a dying system sinking into barbarism versus the affirmation of a class which bears within itself the future flourishing of humanity. The bourgeoisie cannot avoid reacting to the real feelings of indignation and solidarity which are appearing in the central countries.

The spectacular explosion in the number of refugees

The situation is not totally new. In 2012, the High Commission for Refugees (HCR) was already counting 45.2 million “displaced” people and was ringing the alarm bells about this growing human disaster. In 2013, 51.2 million were fleeing various kinds of horror. The threshold of 50 million had thus been crossed for the first time since the Second World War. The HCR explained this as the result of “the multiplication of new crises” and “the persistence of old crises which never seem to die down”. The year 2015 is about to mark a new record: 60 million refugees for Europe alone. Since January, appeals for asylum have increased by 78%. In Germany, according to the minister of the interior, these appeals have quadrupled, reaching the record figure of 800,000. Macedonia has declared a state of emergency and closed its borders. Officially, more than 2800 of these exiles, men, women and children, have drowned in the Mediterranean in the last few months. In Asia, the phenomenon is also massive. For example, a growing number of people have been fleeing repression and persecution in Myanmar and desperately seeking refuge in other southeast Asian countries. In Latin America, criminality and poverty have reached such levels that hundreds of thousands of people are trying to get to the USA. A goods train which goes from the south of Mexico to the north, nicknamed ‘The Beast’, has been regularly carrying thousands of migrants. They run the risk not only of falling from the carriage roofs or being thrown off in the tunnels, but also of being assaulted by the authorities; they are above all at the mercy of the drug gangs or other bandits who ransom them, rape them, kidnap women for prostitution, and as often as not kill them. And for those who have the fortune to get through all this, all along the US frontier they face a wall of barbed wire policed by armed guards who don’t hesitate to shoot at them.

In fact, the hypocritical and civilised speeches of the democratic states go very well with the nastiest and most xenophobic rants. The first encourages feelings of powerlessness, the second of fear. Both obstruct any real reflection, any real development of solidarity.

A phenomenon accentuated by the reality of decomposition

Entire zones of the planet are being devastated and made uninhabitable. This is particularly the case for the regions linking Ukraine to Africa via the Middle East. In certain of these war zones, half the population is in flight and are being held in gigantic camps, at the mercy of the most unscrupulous traffickers, organised on an industrial scale. The real cause of this hell is the decay of the world system of exploitation. The breadth of the refugee phenomenon is a clear expression of the downward spiral of capitalism, which brings in its wake pogroms and violence of all kinds, growing pauperisation linked to the economic crisis, and ecological catastrophes. Of course wars, crises and pollution are not new. All wars have led to people fleeing to save their lives. However, the intensity of these phenomena is growing all the time. Up until the First World War, the number of refugees remained relatively limited. The war then brought the beginning of massive displacements, ‘population transfers’ etc. This spiral took on a whole new dimension with the Second World War, when the number of refugees reached unheard-of levels. Then, during the Cold War, the numerous proxy wars between east and west generated a significant number of refugees, as did the famines in Sub-Saharan Africa in the 70s and 80s. But since the collapse of the eastern bloc in 1989 a veritable Pandora’s box has opened up. The antagonism between the two imperialist blocs imposed a certain order and discipline: most countries obeyed the diktats of their respective bloc leader, the US or Russia. The wars of this period were inhuman and murderous, but in a sense they were ‘ordered’ and ‘classical’. Since the collapse of the USSR, growing instability has given rise to a multiplication of local conflicts, to all sorts of shifting alliances. Conflicts have gone on and on, resulting in the disintegration of states and the rise of warlords and gangsters, in the dislocation of the entire social fabric.

In addition, the contradictions between the imperialist powers (marked by the development of ‘every man for himself’, in which each nation plays its own imperialist card with increasingly short-term objectives), have led the latter to make military interventions in an increasingly regular, almost permanent manner. Each of the big powers support this or that mafia clique or warlord, this or that increasingly irrational band of fanatics, in the defence of their imperialist interests. What dominates in capitalist society today is the disintegration of entire regions, where the most crying expressions of social decomposition can be seen: whole regions controlled by drug gangs, the rise of Islamic State with its barbaric atrocities, etc.

The bunkerisation of the great powers

The states which bear the main responsibility for all this social, ecological and military chaos have at the same time become real fortresses. In a context of unemployment and chronic crisis, security measures are being stepped up to a drastic degree. States have become ‘bunkerised’. Only the most qualified migrants are allowed in to be exploited, to lower the cost of labour power and create divisions within the proletariat. The majority of refugees and migrants, the ‘undesirable’ ones, those reduced to misery and starvation, are cynically enjoined to stay where they are and die without inconveniencing anyone. The northern states have literally chased them into a corner, as in the case of France with its ‘Jungle’ near the Channel Tunnel at Calais. Gangrened by a crisis of overproduction, capitalist society can no longer them any perspective. Instead of opening up, the doors are being closed: states are barricading their frontiers, electrifying fences, constructing more and more walls. During the Cold War, the time of the Berlin Wall, there were about 15 walls defending frontiers. Today more than 60 have been built or are being constructed. From the ‘apartheid wall’ raised by Israel in the face of the Palestinians, to the 4000 miles of barbed wire separating India from Bangladesh, states are falling into a real paranoia about security. In Europe, the Mediterranean front is littered with walls and barriers. Last July, the Hungarian government began construction of a four meter high razor wire fence. As for the Schengen space in Europe, and the work of the Frontext agency or Triton, their industrial-military effectiveness is formidable: a permanent fleet of surveillance and war ships there to prevent refugees from crossing the Mediterranean. A similar military machine has been set up along the Australian coastline. All these obstacles seriously raise the mortality rate among refugees, who are forced to take more and more risks to get past them.

The cynicism of the bourgeoisie

On the one hand, the bourgeois state is barricading itself in. It feeds to the maximum the warnings of doom coming from the most xenophobic populist parties, sharpening hatred, fear and division. Themselves facing deteriorating living conditions, the weakest sections of the proletariat are hit full on by this nationalist propaganda. In a number of countries there have been anti-migrant marches, physical attacks, arson attack on refugee centres. The refugees are the target of campaigns against ‘foreigners who threaten our way of life’. The state legitimises all this by setting up internment camps (over 400 in Europe), deporting those it can, patrolling the frontiers.

On the other hand, this same bourgeoisie fakes its indignation through the voice of politicians who talk about the ‘moral challenge’ posed by the refugees and offers them token support and assistance. In short, the capitalist state, the arch-criminal, poses as their saviour.

But as long as capitalism lasts, there can be no real solution for the migrants and the refugees. If we don’t fight against this system, if we don’t go to the roots of the problem, our indignation and solidarity will not go beyond the stage of basic aid, and the deepest and most noble human feelings will be recuperated by the bourgeoisie, turned into heavily publicised acts of charity which will be used to fuel a more hidden form of nationalism. Therefore, we must try to understand what’s really happening. The proletariat has to develop its own critical and revolutionary point of view on these questions.

In future articles, we will return in more depth to this historic issue.

WH, 6.9.15

Rubric:

The bunkerisation of world capitalism

- 2167 reads

“Nothing is so striking today, nothing has such decisive importance for the whole shape of today’s social and political life, as the yawning contradiction between an economic foundation that grows tighter and firmer every day, binding all nations and countries into a great whole, and the political superstructure of states, which seeks to split nations artificially, by way of border posts, tariff barriers and militarism, into so many foreign and hostile divisions” (Rosa Luxemburg, Introduction to Political Economy, in The Complete Works of Rosa Luxemburg, Volume 1, Verso, London 2013, p 121)

Borders as a demarcation of the ownership of land are as old as the existence of property itself. There simply is no existence of property without the demarcation and defence of it. With the advent of major empires such as the Rome or China, gigantic fortified borders were set up: Hadrian’s Wall, Limes, the Great Wall of China. So the existence of such borders to defend an empire against the invasion of rivals is nothing new.

However, as long as the planet was not yet “divided” amongst the major capitalist rivals, the demarcation of borders still remained mostly at low levels or could even be settled at the negotiation table through treaties. For example in 1884 at the Berlin Conference, borders in Africa could still be drawn on a map; in the early 19th century a territory as big as Alaska was sold by the Russian Czar to the USA. At the turn of the 19th century the Mexican-US border almost had no guards. And at the time of World War One, borders in Europe still were not heavily guarded.

Only once the world had been divided amongst the major capitalist rivals at the turn of the 20th century did the defence of territories become a battle on a different scale. But even though WW1 contained large battles for territories – such as the trench war in Belgium and France, with their terrible cost in human lives and material - the borders remained remarkably ‘open’ after the war. The reparations imposed on the defeated countries by the Versailles Treaty were either a relatively minor loss of territory (the German Saarland, ‘lost’ to France, or the former German colonies, which changed owners) or were made up of big financial payments. However, there was not yet any partition of entire countries, and there were not yet any fortifications of borders as would occur after World War Two.

With the intensification of imperialist rivalries, the defence of borders and territories has changed qualitatively. A fierce fight over every inch of territory set in. After WW 2 a number of countries were divided (Germany, Korea, China, Vietnam, India-Pakistan), all of which set up the most militarised borders, equipped with mines, fences, walls, armed guards and dogs. The formation of the state of Israel in 1948 meant the displacement of hundreds of thousands of Palestinians and the need to entrench itself behind the most sophisticated walls. This has now led to one of the most heavily guarded border walls in the world. “Symbolically, the wall in Palestine is this century’s Berlin Wall, albeit four times as long as that hated Cold War icon and more than twice as high – 8 m.. Under construction since 2002, it is expected to eventually extend for 709 kilometres through the West Bank. A series of concrete slabs, barbed-wire ‘buffer zones’, trenches, electrified fences, watchtowers, thermal-imaging video cameras, sniper towers, military checkpoints and roads for patrol vehicles have dismembered the cities of the West Bank and segregated them from occupied East Jerusalem (…) The wall has cost over $2.6 billion so far, while the cost of yearly maintenance is $260 million”[1].

In sum: since WW1 all countries are imperialist and have to obey the law of defending their interests also through the most obnoxious border defence systems.

And the recent series of wars across the planet has meant that frontiers have been fortified to prevent the infiltration of enemy forces- often terrorist gangs with various states behind them.

A whole system has been set up to screen any person in need of a visa, and Orwellian surveillance institutions like the Homeland Security Authority in the US have been developed to track down possible enemies and prevent them from entering the country.

At the same time while migration in the 19th century was not so much hampered by a complex legislation and a sophisticated police system, the 20th century meant that the borders have now also taken on a second function in addition to the ‘traditional’ military one: to prevent the entrance of labour power that is not needed. Contrast this with the USA’s demand for labour at the end of the 19th century – the real reason for the appeal to “send us your poor, your huddled masses”. Today the USA has joined the race to seal off its southern borders against waves of Latin American proletarians in flight from poverty and criminality in Central and South America.

In the 1960s another new phenomenon appeared. Many of the countries dominated by the Russian bloc had a shortage of labour, in particular East Germany. Thus the East German State erected the Berlin Wall which had to prevent its work force from leaving its territory. The economic underdog closed its borders to keep its citizens inside.

So now more and more we have a simultaneity or double function of borders: in addition to the classical military function of defence of territory, the most sophisticated walls are constructed to prevent refugees from entering and preventing or filtering unwanted “economic migrants”.

So although the Iron Curtain collapsed in 1989, the disappearance of the confrontation between the old blocs did not mean a new borderless world. On the contrary!

“Between 1947-1991 eleven walls were built, which survived the end of Cold War (South-Africa-Mozambique, Zimbabwe, North-South Korea, India-Pakistan, Israel, Morocco-West-Sahara, Zimbabwe-Zambia). Between 1991-2001 seven walls were erected: Around the exclaves Ceuta, Melilla, USA-Mexico, Malaysia-Thailand, Kuweit-Iraq, Uzbekistan-Afghanistan/Kirgizistan). 22 walls were erected since 2001: Saudi-Arabia-United-Arab Emirates, Iraq, Oman, Qatar, Yemen, Burma-Bangladesh, Botswana-Zimbabwe, Brunei-Malaysia, China-North-Korea, Egypt-Gaza-strip- United Arab Emirates-Oman, India-Bangladesh, Burma-Pakistan, Iran-Pakistan, Israel-Jordan/West-Bank, Jordan-Iraq, Kazakstan-Uzbekistan, Pakistan-Afghanistan, Thailand-Malaysia- Turkmenistan-Uzbekistan, Israel-Egypt.

(www.dandurand.uqam.ca/evenements/evenements-passes/440-fences-and-walls-... [10] also Chaire Raoul-Dandurand _ Fences and Walls in International Relations.html, Berlin Wall is Gone but Separation Walls are a Growth Industry _ Burning Billboard.org.htm)

Between the almost 200 countries of the world there are some 250,000 kilometers of borders. An entrenched society![2]

This shows the totally irrational character of the capitalist system. While capitalism can only ‘prosper’ if there is free mobility of goods and labour, the movement of human labour is submitted to the most ruthless checks and obstacles. This means not only an unknown level of violence along the borders, but also totally lunatic financial costs. The massive border protection system between Mexico and the US costs a fortune: “But that has come at a cost. Most estimate inspection, patrol, and infrastructure set taxpayers back somewhere between $12 billion and $18 billion per year. That's up about 50% from the early 2000s, according to the Journal, which says spending has included ‘everything from 650 miles of fencing to military aircraft, marine vessels, drones, surveillance equipment, infrared camera towers and detention centres’. More generally, border security costs totalled $90 billion between 2002 and 2011, a Freedom of Information Act request conducted by the Associated Press shows. The news outlet reports that annual expenses vary from drug-sniffing dogs -- $4,500 each -- to National Guard troops -- about $91,000 per soldier”. (Source https://www.fool.com/investing/general/2014/08/06/the-migrant-crisis-could-cost-billions-but-border.aspx [11])

If you imagine the total number of guards all along the borders in the world, their cost would be the most absurd figure – and it shows graphically what this society wastes its resources on! [3]

We should add that, along with the most sophisticated border controls, within each country more and more “gated communities” are set up, fences and often armed protection systems for the privileged. Entire neighbourhoods have become “no-go-areas” for non-residents.

But the industrial countries are not only becoming real “bunkers”. They are also the biggest “deporters” of labour-power. While the total number of slaves who were taken by force mainly from the African continent amounts to some 10-20 million during period 1445-1850, the deportation policy by the industrialised countries and even other states will probably reach a similar number in a much shorter span of time. A few examples: more than 5 million ‘illegal’ immigrants have been deported from the US - under G.W. Bush around 2 million, under Clinton almost 900,000, and under Obama more than 2 million. In Europe the measures are tougher and tougher, and there about 400 detention centres for ‘illegals’ awaiting deportation. Mexico itself deports 250,000 foreigners a year to Central America. Saudi Arabia is to deport more than one million people who live and work illegally in the kingdom.

Faced with the recent wave of refugees from the war torn areas of the Middle East, Afghanistan, Northern Africa... the system of border protection has reached a new scale. The authorities deploy ever more troops and material to detain and deport refugees. More than a quarter of a century after the “opening” of the Iron Curtain in Hungary, Hungary has sealed its border with Serbia with barbed wire to prevent “Les misérables” from reaching “safer havens”, and it is planning to set up another Iron Curtain along the Romanian border. Similar measures are being taken in other European countries. The previously “open” Schengen borders are now controlled by border police; “hotspots” (refugee ‘selection’ centres are to be set up in Greece and Italy, with the possibility of sending back refugees to the inferno where they came from. Or outposts for holding back refugees are extended to Africa itself, where arrangements are made to set up border controls at the refugee transit routes in Africa.

The pictures of refugee treks and thousands of detained or repulsed refugees on the Balkans and elsewhere, left without food and shelter, remind us of the way the Jewish population was treated under the Nazi regime or the fate of the refugees at the end of World War Two. They show the continuity of barbarism in this system. A century of war refugees, of camps, of deportations, of Iron Curtains, of illegal migration and deportation of those who have the cheek to come only to fill their bellies.

We now have the highest and longest walls ever to prevent war refugees and desperate ‘economic’ migrants from entering – but they still cannot stem the tide of victims of the combined effects of capitalism’s inexorable decomposition.

By creating a global economy, capitalism has created the conditions for a world wide human association. But its total inability to realise it is illustrated today by the universal fortification of its frontiers. Calls for ‘no borders’ by well-meaning activist groups are thus entirely utopian. Borders can only be abolished through international proletarian revolution, which will dismantle the anti-human prison of the nation state.

Dv. 09.09.15

[2] Worldwide 500,000 tonnes of barbed wire are produced every year. This is good for 8 million km of barbed wire, i.e. 200 times the circumference of the earth.

[3] And the amount of money refugees have to pay to human traffickers has also reached unheard of proportions.

Heritage of the Communist Left:

Rubric:

Tianjin: Verify everything, don’t forget anything!

- 1567 reads

On August 12th, at 22.50 (China local time), there was a warning of a small fire in one of the industrial warehouses in the district of Bihai, in the port city of Tianjin, China. Some firemen rushed to the scene. Some 40 minutes later, there was a tremendous explosion equivalent to 3 tons of TNT, and some seconds after that another brutal explosion, equivalent to 21 tons of TNT, which could be seen even via satellites surrounding the earth.

Why was this explosion so terrible? These warehouses are not just the usual ones; they were warehouses of dangerous products with more than 3 tons of products potentially harmful to any human being. All of them were situated in an industrial zone where only workers are living.

It seems that the calcium carbide that was stored could have reacted with the water that was used by the firemen to extinguish the fire, transforming itself into an explosive acetylene. An explosion of acetylene would have been enough to detonate a chain reaction of other products that were stored there, causing an even far bigger one. At the moment there are 114 deaths and initially 720 people have been treated in hospitals. We should add that the warehouse had also stored 700 tons of sodium cyanide, a highly toxic substance for human beings; and there is fear that it might have intoxicated the whole zone.

The destructive logic of capital

Behind all these facts and figures one thing is hidden: the inhuman logic of capital, a new infliction on the working class, paid for in blood, a new offensive against everything that is human on this planet. In 1915, in his pamphlet ‘The enemy is in our own country’, the revolutionary Karl Liebknecht said: “The enemies of the people are hoping that the masses will forget… We fight this with the following means: Verify everything, don’t forget anything! Don’t forgive anything!”.

This slogan is still valid today. Why was there a warehouse stuffed with such material, if not for the need to reduce costs, to maintain the accumulation of capital? Why have workers been living so close to these monstrous piles of explosives, if not because the Moloch of capital needs to maximise the use of space filled by the exploited and humiliated population?

We need to remember that those accidents are not isolated cases, but a chronic problem of capitalism in general and Chinese capitalism in particular. In its Sunday edition of 23rd of August, the Spanish newspaper El País titled its report: ‘Industrial insecurity: an endemic problem in China’. There we are told that between January and May 2015, industrial accidents caused 16.000 deaths and there were 26 explosions like the one in Tianjin, with a total of 65 deaths. China is not an exception according to the ILO (International Organisation of Labour), because in 2014 2,300,000 people died as a result of industrial across in the world.

In its phase of decomposition capitalism loses its capacities for a ‘healthy’ coordination and functioning, what little was there in the first place. For this reason they sent firemen to extinguish a fire in a warehouse that was full of substances that reacted violently when they came into contact with water. So they lost their warehouse, their industrial infrastructure and the port activities came to a standstill in a port which is a transit point for 40% of all imported vehicles. The mining giant BHP Billiton suspended all its port activities. Renault lost 1,500 cars and Hyundai 4,000. Toyota and John Deere halted their production. 17.000 buildings are damaged…. Capitalism's crazy drive for accumulation is turning against itself, like a gigantic fist. Capitalism is demonstrating that its survival generates monstrous contradictions, which are increasingly difficult to control and which lead to ever more dangerous waves of destruction.

But if the bourgeoisie suffered losses with this self-inflicted catastrophe, the proletariat has lost more. What does all the industrial production of Toyota, John Deere and BHP mean, compared to the life of one single worker? To all those workers who lost their home or even worse, to the workers which this infamous government wants to relocate to this zone, even though is poisoned with cyanide? Nothing!

Against this cruel reality, against these continuing humiliations imposed by the bourgeoisie and the Chinese government, there have already been some small protests.

But these protests seem to be sunk in the swamp of democratism and legality: “they did not know about the content of the warehouse when they should have known it…it was too close to habitations according to the existing law…”

A real proletarian voice is still needed in China, a voice that says clearly: no to the assassination of our class brothers, no to the servile and inhumane factory-cities and no to the shameless logic of capital. There has to rise, finally, a voice that speaks for what is human in man. In the meanwhile we all want to be that voice:

Verify everything, don’t forget anything! Don’t forgive anything! Tianjin is murder!

Comunero 24.8.15

This article was contributed by a sympathiser of the ICC in Spain.