International Review no.33 - 2nd quarter 1983

- 3274 reads

A Hundred Years After The Death Of Marx, The future belongs to Marxism

- 2577 reads

Karl Marx died on the 14th March 1883. It is thus 100 years since the workers' movement lost its greatest, theoretician.

The bourgeoisie -- this class that Marx fought untiringly all his life and which paid him back in kind -- is preparing to celebrate this centenary in its own way by heaping new mountains of lies over Marx and his work.

Each fraction goes about this in its own way, according to the particular interests it has to defend and its specific place in the apparatus of mystification.

Those for whom Marx was ‘an evil being', a kind of ‘incarnation of wrong' or ‘creature of the devil', have practically disappeared. They are in any case the least dangerous today.

By contrast, there are any number left of those for whom Marx, while ‘always remaining a very intelligent and cultivated man, was nonetheless completely mistaken'; a variation on this lie is the one that says ‘while Marx's analysis was valid in the 19th century, it is now completely out of date'.

However, the most dangerous are not those who reject Marx's work explicitly. Rather, it is those who claim to continue it, whether they belong to the social-democratic, the Stalinists, the Trotskyists, or that we might call the ‘university- -- ‘marxologist' - branch of the ruling class.

At the centenary of Marx's death, we shall see all these fine gentlemen get very agitated, make a lot of noise, speak authoritatively, invading the columns of the press and the television screen. It is thus up to revolutionaries to refute this thickly-woven tissue of lies, to sweep away all these self-interested panegyrics, and so establish the simple truth of plain facts and this, moreover, is the real homage they have to render Marx and his work.

Is Marx out of date?

Marx uncovered the underlying secret of the capitalist mode of production: the secret of surplus value, appropriated by the capitalists thanks to the unpaid labor of the proletarians. He showed that work impoverished the proletarian instead of enriching him, and that crises become more and more violent because the need for outlets inreases while the world market contracts. He took on the job of showing that its own laws drive capitalism to its destruction and create the conditions for, and the necessity of, the communist revolution. Born covered in blood and filth, fed like a cannibal on the proletarians' labor-power, capitalism would leave the scene in a cataclysm.

This is why the bourgeoisie, for a hundred years, has fought the ideas of Marx. Army upon army of ideologues has tried again and again to wipe his thought from the earth. Preachers and learned professors have made a business out of ‘refuting' Marx. Through its schools and universities, the bourgeoisie has kept up a continual barrage of fire against Marx. Within the workers' movement itself, the revisionists attacked Marxism's fundamental principles in the name of its ‘adaptation' to the new realities of the period (end of the 19th Century). It was, moreover, no accident that Bernstein, the theoretician of revisionism, set himself to attack marxism on two fundamental points:

-- capitalism's supposed discovery of a way to overcome its catastrophic economic crises;

-- the supposed diminution in the exploitation of the working class to the point where it would eventually disappear.

These are the two main ideas that the bourgeoisie has frantically advertised every time that the economic situation has apparently improved to the point of allowing a few crumbs to the working class. This was particularly the case in the reconstruction period following the Second World War, where economists and politicians were to be heard announcing the disappearance of crises. Thus, in his book Economics Samuelson (a Nobel prizewinner for economics) exclaimed, "everything is happening today as if the probability of a great crisis - a profound, sharp and durable depression of 1930, 1870 or 1890 - had been reduced to zero." (p. 226)

President Nixon, for his part, confidently declared on his day of inauguration (January 1969) that "we have at last learned to manage a modern economy in such a way as to ensure its continued expansion."

And so, until the beginning of the 1970s, those for whom ‘Marx is out of date' spoke with great authority[1]. Since then, the clamor has died down. Inexorably, the crisis unfolds. All the magic potions prepared by the Nobel prizewinners of different schools have failed and have only mada matters worse. Capitalism is beating all the records: record indebtedness, a record number of bankruptcies, record under-utilization of productive capacity, record unemployment. The specter of the Great Crash of 1929 and the crisis that followed has returned to haunt the bourgeoisie and its appointed professors. Blind optimism has given way to black pessimism or disarray. Some years ago the Nobel prizewinner Samuelson noted sadly "the crisis of economic science" which had shown itself incapable of providing solutions to the crisis. Eighteen months ago, the Nobel prizewinner Friedman confessed that "he no longer understood anything". More recently, the Nobel prizewinner Von Hayek stated that "the Crash is inevitable" and that "there is nothing to be done".

In his postface to the 2nd German edition of Capital, Marx observed that the "general crisis ..., by the universality of its action and the intensity of its effects was to ram the dialectics even into the heads of those scribblers who sprouted like mushrooms" during one of capitalism's prosperous phases. The economists, those scribblers par excellence, are once again going through the same experience: the crisis unleashed today is beginning to make them intelligent. They are beginning to discover, to their great alarm, that their 'science' is impotent, and that there is "nothing to be done" to rescue their beloved capitalism from the abyss.

Not only is Marx not ‘out of date' today; it needs saying loud and clear that never before have his analyses been so clearly relevant.

The whole history of the 20th Century is an illustration of the validity of Marxism. Two world wars and the crisis of the 1930s proved that capitalism cannot overcome the contradictions of its mode of production. Despite its defeat, the revolutionary upsurge of 1917-23 confirmed that the proletariat is indeed today's only revolutionary class, the only social force capable of overthrowing capitalism, of being the ‘gravedigger' (as the Communist Manifesto put it) of this dying system.

Today's acute and deepening capitalist crisis is sweeping away the illusions sowed by the second post-war reconstruction. The illusion has fallen of an eternally prosperous capitalism, of ‘peaceful coexistence' between the great imperialist blocs, of a ‘bourgeoisified' working class and ‘the end of the class struggle', the latter demonstrated since May ‘68 by the historic resurgence of the working class and amply confirmed in particular by the battles in Poland in 1980. Once again, the alternative pointed to by Marx and Engels reappears in all its clarity: "socialism or a fall into barbarism".

The first homage paid to Marx's thought on the centenary of his death thus comes from the very facts of the crisis, the ineluctable aggravations of the convulsions of capitalism, the historic resurgence of the class struggle. What better homage could there be to him who wrote, in 1844: "The question of whether objective truth can be attributed to human thinking is not a question of theory, but is a practical question. In practice man must prove the truth, that is, the reality and power, the this-sidedness of his thinking." (Theses on Feuerbach)

Marx used against the working class

"During the lifetime of great revolutionaries, the oppressing classes relentlessly persecute them and treat their teachings with malicious hostility, the most furious hatred and the most unscrupulous campaign of lies and slanders. After their death attempts are made to canonize them, so to speak, and to surround their names with a certain halo for the ‘consolation' of the oppressed classes and with the object of duping them, while at the same time emasculating the revolutionary doctrine of its content, vulgarizing it and blunting its revolutionary edge." (Lenin, State and Revolution)

These words of Lenin's, written in 1917 against the Social-Democracy and especially against its ‘pope' Karl Kautsky, have since been borne out on a scale their author never dreamed of. He himself was transformed literally after his death into a ‘harmless icon' since his mummy remains a place of pilgrimage to this day.

The degenerating Social-Democracy which passed openly to the bourgeois camp had already done much to ‘emasculate' Marx's thought and empty it of its revolutionary content. While the first offensive against marxism - Bernstein's at the end of the 19th Century -- proposed to ‘revise' this theory, Kautsky's offensive of around 1910 was conducted in the name of ‘marxist orthodoxy'. Through a careful choice of quotations, Marx and Engels were made to say the exact opposite of their real thought. This was the case in particular on the question of the bourgeois state. Kautsky passed in silence over Marx's repeated insistence, after the Paris Commune, of the need to destroy the state and went on to hunt out quotations that might give some credence to the opposite idea. And since revolutionaries, even the greatest, are not immune from ambiguities, or even mistakes, Kautsky succeeded in his aim -- to the profit of the Social-Democracy's reformist practice, and to the great loss of the proletariat and its struggle.

But the ignominy of the Social-Democracy did not stop at falsifying Marxism. This falsification, after preparing the proletariat's total demobilization in the face of the threat of war, announced Social-Democracy's complete betrayal, its passage body and soul into the bourgeois camp. In the name of ‘marxism' it jumped feet first into the blood and filth of the first imperialist war; in the name of ‘marxism' it helped the world bourgeoisie fill the breach opened in capitalism's edifice by the October Revolution; in the name of ‘marxism' in 1919 it coldly ordered the murder of Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Liebknecht, and thousands of Spartakists. By usurping Marx's name the Social-Democracy won ministerial portfolios in bourgeois governments, positions as prefects of police or colonial governors. In Marx's name, it undertook to be the executioner of the European proletariat and the colonial populations.

But however abject the debasement of social-democracy, it was completely surpassed by Stalinism.

The social-democratic falsifications of marxism were nothing beside those of the Stalinists. Never have the bourgeoisie's ideologues been so cynical in deforming the slightest phrase to give it a meaning exactly contrary to its real one.

While internationalism and the total rejection of chauvinism were the cornerstone of both the October Revolution and the foundation of the Communist International, it was left to Stalin and his accomplices to invent the monstrous theory of ‘building socialism in one country'. In the name of Marx and Engels, who had written in 1847: "The communist revolution will not be a purely national revolution, it will occur simultaneously in all the civilized countries .... It is a universal revolution, and so will have a universal terrain" (Principles of Communism) and "The workers have no fatherland" (Communist Manifesto) -- in their name, the degenerated Bolsheviks and other so-called ‘communist' parties called for ‘the construction of socialism in the USSR', for the defense of the ‘socialist fatherland', and later for the defense of the national interest, of flag and fatherland in their respective countries. The jingoism of the socialists in 1914 pales by comparison with the stalinist parties' hysterical chauvinism before, during and after the second imperialist butchery -- the "To every man his Bache" and the "Long live eternal France" of L'Humanite (newspaper of the Parti Communiste Francais) in 1944[2].

In the hands of the stalinists, marxism, enemy of religion and a more consistent enemy of the state than anarchism has ever been, has become a state religion and a religion of the state. Marx, who always considered liberty and the state to be incompatible, slavery and the state to be indissolubly linked, is used as an ideological knout by the powers that be in Russia and its satellites, and has been turned into a pillar of the repressive police apparatus. Marx, who began his political life in the struggle against religion, which he described as "the opium of the people", is now recited like a catechism by school children in their hundred thousands. In the name of the dictatorship of the proletariat, which Marx saw as the condition for the emancipation of the exploited and the whole of society, the bourgeoisie exercises a brutal reign of terror over millions of proletarians.

After the revolutionary wave that followed the First World War, the working class suffered the most terrible counter-revolution in history. The spearhead of this counter-revolution was the ‘socialist fatherland' and the parties that defended it. And this counter-revolution, with its millions of dead in its stalinist concentration camps and in the second imperialist holocaust, was conducted in the name of Marx and in the name of the communist revolution for which he struggled all his life.

Stalinism has repeated tenfold all the ignominies the Social-Democracy could boast of.[3]

Marx: savant or militant?

It has not been enough for the bourgeoisie to transform Marx and marxism into symbols of the counter-revolution. To finish off the job, it has turned marxism into a university discipline, the subject for theses in philosophy, sociology and economics. On the centenary of Marx's death, we can therefore expect plenty of activity alongside the socialists and stalinists from the ‘marxologist' (who are frequently socialists or stalinists, moreover). A sinister irony! Marx, who refused a university career in order to devote himself to the revolutionary struggle, is relegated to the ranks of the philosophers, economists and other bourgeois ideologues.

It is true that, in many realms of thought, there is a ‘before' and ‘after' Marx. This is especially true in economics; this discipline was completely transformed by Marx's enormous contribution to the comprehension of society's economic laws. But this phenomenon is by no means the same as, for example, the discovery of an important new theory in physics. In the latter case, the discovery forms the point of departure for an advance in knowledge (so the ‘after' Einstein, for instance, constitutes a considerable deepening in the study of the laws of the Universe). By contrast, Marx's discoveries in economics inaugurated, not an advance, but on the contrary an immense regression. The reason for this is very simple. The economists who preceded Marx were the intellectual representatives of a class that incarnated historical progress, of a revolutionary class against feudal society: the bourgeoisie. Despite their inadequacies, Smith and Ricardo could push forward society's knowledge because they defended a mode of production -- capitalism -- which at the time constituted a progressive step in the evolution of society. Faced with the obscurantism of feudal society, they needed to deploy all the scientific rigor that their epoch made possible.

Marx acknowledged and used the work of the classical economists. His objective, however, was completely different. If he studied the capitalist economy, it was not to try and improve its functioning but to combat it and prepare for its overthrow. This is why he did not write a ‘Political Economy', but a ‘Critique of Political Economy'. And it is precisely because, in studying bourgeois society, he did so from the standpoint of its revolutionary overthrow that he was so well able to understand its laws. Only the proletariat, a class which has no interest in the preservation of capitalism, could lay bare its mortal contradictions. If Marx was able to make such progress in understanding the capitalist economy, this is above all because he was a fighter of the proletarian revolution.

After Marx, any new progress in the understanding of the capitalist economy could only be made with his discoveries as point of departure, and therefore from the same class standpoint. By contrast, bourgeois political economy, which by its very nature rejects this standpoint, could no longer be anything other than an apologetic, a discipline aimed at justifying capitalism's preservation by whatever argument came to hand, and so inherently unable to understand its real laws. This is why today, even the brightest economists look like cretins.

Marxism is the theory of the proletariat; it cannot be a university discipline. Only a revolutionary militant can be a marxist. This unity of thought and action is precisely one of marxism's foundations. It is clearly expressed as early as 1844 in the Theses on Feuerbach, and especially in the last one: "The philosophers have only interpreted the world in various ways; the point, however, is to change it."

Some have tried to make Marx out as a scholar shut away with his books from the world outside. Nothing could be further from the truth. When, one day, one of his daughters made him play the parlor-game, ‘Confessions', (the answers were published later by Riazanov) and asked him his idea of happiness, he replied: "struggle". And like any revolutionary militant, the struggle was at the centre of his life.

As early as 1842, before he had yet committed himself to communism, he began his political struggle against, Prussian absolutism on the editorial committee, and later as director, of the Rheinische Zeitung. Thereafter, this untiring fighter was expelled from one country to another by the various European authorities until he finally settled in London in August 1849. In the meantime, Marx had taken part directly in the battles of the revolutionary wave that shook all Europe in 1848-49. He took part in these struggles at the head of the Neue Rheinische Zeitung, in which he had invested all his savings. But he made his most important contribution to the proletarian struggle through his role in the Communist League. For this was always Marx's approach: unlike some of today's pseudo-marxists, he considered the organization of revolutionaries as an essential instrument of the proletarian struggle. The most famous and the most important text of the workers' movement -- the Communist Manifesto written by Marx and Engels in 1847 -- was in fact entitled the Manifesto of the Communist Party and constituted the program of the Communist League, which the two friends had joined a few months previously, after "the elimination from the Statutes of everything that favored authoritarian superstition." (Marx).

Just as he played a major role in the development of the Communist League, so he played a leading part in the foundation and life of the First International -- in other words, the first great worldwide organization of the proletariat. To him we owe the International's inaugural address and Statutes as well as most of its fundamental texts, in particular the address on the Civil War in France written during the Paris Commune. But this was not his only contribution to the life of the International. In fact, between 1864 and 1872 he was continuously and untiringly active in the International's General Council whose main driving force he was, though without ever taking credit for it. His participation in the life of the International cost him an immense time and energy which he was unable to devote to the completion of his theoretical work, Capital, whose first volume only was published in 1867, the rest being published after his death by Engels. But this was a deliberate choice on his part. He considered his activity as a militant of the International as fundamental because this was the living organization of the world working class, the class that in freeing itself would free all humanity. As Engels wrote: "Marx's life without the International would have been like a gem-stone without its setting."

In the profundity of his thought, the rigor of his reasoning, the breadth of his learning and his untiring search for new knowledge, Marx indubitably takes on the appearance of a ‘great scholar'. But his discoveries never brought him honors or official titles, nor material advantage. His commitment to the working class' cause, which lent energy to his theoretical work, earned him, on the contrary, the permanent hatred and antagonism of the ‘respectable society' of his time. It also meant that he struggled for most of his life against an extreme material poverty. As his biographer Franz Mehring wrote: "Not only in the poverty of his way of life, but in the total insecurity of his whole existence, Marx shared the lot of the modern proletarian."

But never was he diverted from his fight, neither by adversity, nor even by the cruelest defeats suffered by the proletarian struggle. Quite the reverse. As he himself wrote to Johann Philipp Becker: "... all really well-tempered characters, once they are engaged on the revolutionary path, constantly drain new strength from defeat and become ever more resolute the further the river of history carries them."

To be a marxist today

In all the history of human thought, there has never been a great thinker who has not been involuntarily betrayed by one or other of his disciples. Marx, who even during his lifetime saw his method of analysis of reality transformed into a facile catch-phrase, was not immune from this common fate. He denied in advance all responsibility for the emasculation of his theoretical method by certain social-democrats. Instead of a sterile scholasticism, he intended that they should study a society in constant revolution with the help of a method, and not that they should indiscriminately transform everything he said into an unvarying law.

To seek in Marx, solutions ready-made for artificial transplantation from a past epoch into a new one is to crystallize a thought that was constantly alert and spurred on by the desire to remain a critical weapon. Thus, rather than uncritically accepting everything that comes from Marx, the marxist today must determine exactly what still serves the class struggle and what has ceased to do so. In a series of letters to Sorge (1886-1894), Engels urges him to avoid all bigotry since, in his own words, Marx never claimed to be setting up a rigid theory, an orthodoxy. For us, to reject a so-called ‘invariant' doctrinarism means to reject a contradiction in terms: an eternally true theory, the Word that creates Action and awaits only its catechists to become Action.

This ‘invariance' is nowhere to be found in Marx's work, for it is incapable of distinguishing the transitory from the permanent. No longer corresponding to a new situation, it is useless as a method for interpreting reality. Its truth is deceptive, despite its repeated pompous assertions.

"Such ideas are only of interest to a satiated class, that, feels at ease and confirmed in the present situation. They are worthless for a class that struggles and tries to go forward and is necessarily unsatisfied by the situation as it is." (Karl Korsch, At the Heart of the Materialist Conception)

To be a marxist today does not therefore mean sticking to the letter of everything Marx wrote. This would, moreover, be difficult to the extent that numerous contradictory passages are to be found in Marx's work. Nor is this at all a proof of any incoherence in his thought: on the contrary, even his adversaries have always recognized the extraordinary coherence of his thought and method. In fact, it is a sign of the living quality of his thought, of the fact that it was constantly alert to reality and historical experience; in the image of the "proletarian revolutions (which) ... criticize themselves constantly, interrupt themselves continually in their own course, come back to the apparently accomplished in order to begin it afresh, deride with unmerciful thoroughness the inadequacies, weaknesses and paltrinesses of their first attempts ..." (Marx, The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte) Marx never hesitated to go back on his earlier analyses. Thus he recognized, in the preface to the 1872 German edition of the Communist Manifesto that "no special stress is laid on the revolutionary measures proposed at the end of Section II. That passage would, in many respects, be very differently worded today ... One thing especially was proved by the Commune, viz; that, ‘the working class cannot simply lay hold of the ready-made state machinery and wield for its own purposes'."

This is the approach of real Marxists. It was Lenin's method in 1917 when he fought against the Mensheviks who stuck to the letter of Marx in order to support the bourgeoisie and oppose the proletarian revolution in Russia. It was Luxemburg's in 1906 when she came up against the union bosses who condemned the mass strike on the basis of an 1873 text of Engels written against the anarchists and their myth of the ‘general strike'. It was precisely in the name of marxism that she defended the mass strike as the essential weapon of the proletarian struggle in the new period:

"If, therefore, the Russian revolution makes it indispensable fundamentally to revise the previous marxist view of the mass strike, it is nonetheless the method and general viewpoint of marxism which emerges from it victorious, in a new form." (Mass Strike, Party and Unions)

To be a marxist today means using the "method and general viewpoints of Marxism" in defining the tasks fixed for the proletariat by the new period of capitalism opened up by the First World War: its decadence as a mode of production.[4]

In particular, it means using the same method that led Marx and the First International to encourage the workers' unionization, to denounce all forms of unionism. It means denouncing any participation in Parliament or elections from the same viewpoint as Marx and Engels when they fought against the abstentionism of the anarchists. It means refusing all support to today's so-called ‘national liberation' struggles, using the same method as the Communist League and the International used in understanding the need to support certain of the national struggles of their time. It means rejecting the conception of the mass party in the coming revolution, for the same fundamental reasons that made the First and Second Internationals mass organizations.

To be a marxist today means drawing the lessons from the whole experience of the workers movement, from the successive contributions of the Communist league, of the First, Second and Third Internationals, and of the left fractions that split from the latter as it degenerated, in order to enrich the proletarian battles that have broken out since 1968 in response to the capitalist crisis and to arm them for the overthrow of capitalism.

RC/FM

[1] It is important to pint out that the confessed defenders of the capitalist system were not alone in putting forward this idea. During the 1950s and ‘60s a tendency developed in certain groups claiming to defend the communist revolution to call into question the fundamental basis of marxism. Thus the group Socialisme ou Barbarie, led by its ‘great theoretician' Castoriadis (alias Chaulieu-Cardan) built up a theory of the ‘dynamic of capitalist', affirming that Marx was totally mistaken in trying to prove that the system's economic contradictions could not be resolved. Since then, things have fallen into place again: professor Castoriadis has distinguished himself with his ‘left' justification of the Pentagon's war effort by publishing a book that ‘demonstrates' that the USSR has an enormous military advance on the USA (!). Naturally enough, for Castoriadis, his rejection of Marxism has opened wide the doors of the bourgeoisie.

[2] Clearly, this in no way either excuses the crimes of Social-Democracy or diminishes their seriousness. The proletariat has no choice to make between the plague of Social Democracy and the cholera of Stalinism. Both pursue the same goal: the preservation of capitalism, with methods that may vary following the particular characteristics of the countries where they act. What makes Stalinism still more shameful than the Social-Democracy is its extreme position within decadent capitalism, within its evolution towards the historical form of state capitalism and its development of state totalitarianism. In backward countries, where the private bourgeoisie is undeveloped and already senile, this inexorable process of capital demands a particularly brutal political force, capable of the bloody installation of state capitalism. This political force appears, according to country, as a military dictatorship or as Stalinism which not only maintains a bloody repression but claims to be doing so in the name of ‘socialism', ‘communism' or ‘marxism', so beating every record for ignominy and cynicism.

[3] With their modest means, the Trotskyists have fallen into step with their big brothers, Social-Democracy and Stalinism. They invoke Marx and Marxism with an exaggerated vehemence (witness the Parti Communiste Internationaliste, the ‘lambertiste' tendency, launching a fund to republish the biography of Marx written by Franz Mehring) when for more than forty years they have not missed an opportunity to give ‘critical' support to Stalinist ignominies (the Resistance, defense of USSR, glorification of so-called ‘national liberation struggles', support for left governments).

[4] Within the limits of this article, we are unable to go over all the implications of capitalist decadence for the methods of the working class struggle. On this subject, see the ICC's Platform and the article The Proletarian Struggle in Capitalist Decadence, in IR 23.

Heritage of the Communist Left:

General and theoretical questions:

- Communism [2]

Report on the structure and functioning of the revolutionary organisation

- 7138 reads

1. The structure adopted by an organisation of revolutionaries corresponds to the function it takes up within the working class. Since a revolutionary organisation has tasks which apply to all stages of the workers' movement and also has tasks which are more particular to this or that juncture in the movement, there are constant characteristics of the organisation of revolutionaries and characteristics which are more circumstantial, more determined by the historic conditions in which it emerges and develops.

Some of these constant characteristics are:

-

the existence of a programme valid for the whole organisation. This programme, because it is a synthesis of the experience of the proletariat of which the organisation is a part and because it is produced by a class which doesn't just have an immediate existence but also a historic future;

-

expresses this future by formulating the goals of the class and the way to attain them:

-

gathers together the essential positions which the organisation must defend in the class;

-

serves as a basis for joining the organisation;

-

-

its unitary character - expressing the unity of its programme and of the class which it emanates from. The practical manifestation o~ this unity is the centralisation of its structure.

Some of its more circumstantial characteristics are:

-

the greater or lesser scale of the organisation, depending on whether it is a product of the first groupings of the workers' movement (secret societies, sects), or of the stage when workers' parties were in their full development inside capitalist society (mass parties of the Second International) or of the period of direct confrontation with capitalism (the period opened by the revolution of 1917 and the foundation of the Communist International) which imposed on the organisation stricter and narrower criteria for selection.

-

the level at which its programmatic and organic unity is most directly manifested: the national level when the working class faced specific tasks within an expanding capitalism in the various countries where the struggle was going on (parties of the Second International); the international level when the proletariat has only one great task to accomplish: the world revolution.

2. The ICC's mode of organisation directly corresponds to these different points:

-

organic and programmatic unity on an international scale;

-

'narrow' organisation, with strict criteria for joining.

But this unitary international character is more marked with the ICC than with the organisations which emerged previously in the period of decadence (CI, Left Fractions). This is because there is no organic link with the organisations coming out of the Second International whose country-by-country structure was much more marked. This is why the ICC emerged straight away as an international organisation which subsequently gave rise to further territorial sections, and not as the result of a process of coming together by organisations already constituted on the national level.

This 'positive' result of the break of organic continuity is however counterbalanced by a whole series of weaknesses connected to this break and concerning the understanding of questions of organisation. These weaknesses are not limited to the ICC but concern the whole revolutionary milieu. It is these weaknesses which have manifested themselves once again in the ICC and which have motivated the holding of an international conference and the present text.

3. At the centre of the incomprehensions which plague the ICC is the question of centralism. Centralism is not an optional or abstract principle for the structure of the organisation. It is the concretisation of its unitary character. It expresses the fact that it is one and the same organisation which takes positions and acts within the class. In the various relations between the parts of the organisation and the whole, it's always the whole which takes precedence. In the face of the working class you cannot have political positions or conceptions of intervention which are particular to this or that territorial or local section. These latter must always see themselves as part of a whole. The analyses and positions expressed in the press, leaflets, public meetings discussions with sympathisers, the methods used in our propaganda and in our internal life are those of the organisation as a whole, even if there are disagreements with this or that point in this or that place or with this or that militant, and even if the organisation expresses in public the political debates going on within it. We must absolutely reject the conception according to which this or that part of the organisation can adopt, in front of the organisation or of the working class, the positions or attitudes which it thinks correct instead of those of the organisation which it thinks incorrect. This is because:

-

if the organisation is going in the wrong direction, the responsibility of the members who consider that they defend the correct position is not to save themselves in their own little corner, but to wage a struggle within the organisation in order to help put it back in the right direction[1];

-

such a conception leads a part of the organisation to arbitrarily impose its own position on the whole organisation with regard to this or that aspect of its work (local or specific).

In a revolutionary organisation the whole is not the sum of the parts. The latter are delegated by the whole organisation to carry out a particular activity (territorial publications, local interventions, etc), and are thus responsible in front of the whole for the mandate they have been given.

4. The highest moment in the unity of the organisation is its International Congress. It is at the International Congress that the programme of the ICC is defined, enriched, or rectified; that its ways of organising and functioning are established, made more precise or modified; that its overall orientations and analyses are adopted; that a balance sheet of its past activities is made and perspectives for future work drawn up. This is why preparation for a Congress must be taken up by the whole organisation with the greatest care and energy. This is why the orientations and decisions of a Congress must serve as a constant point of reference for the whole life of the organisation in the ensuing period.

5. The unity and continuity of the organisation between Congresses is expressed by the existence of central organs nominated by the Congress and responsible to it. It's the central organs which (according to whether they are international or territorial organs) have the responsibility:

-

to represent the organisation to the outside world;

-

to take positions whenever necessary, on the basis of orientations defined by the Congress;

-

to co-ordinate and orientate all the activities of the organisation;

-

to watch over the quality of our intervention towards the outside world, especially in the press;

-

to animate and stimulate the internal life the organisation, notably by circulating internal discussion bulletins and taking up positions on debates when necessary;

-

to manage the financial and material resources of the organisation;

-

to carry out all the measures necessary for maintaining the security of the organisation

-

to call Congresses.

The central organ is a part of the organisationand as such is responsible to it, when it meets at its Congress. However it's a part whose specificity is that it expresses and represents the whole, and because of this the positions and decisions of the central organ always take precedence over those of other parts of the organisation taken separately.

Contrary to certain conceptions, notably so-called 'Leninist' ones, the central organ is an instrument of the organisation, not the other way round. It's not the summit of a pyramid as in the hierarchical and military view of revolutionary organisation. The organisation is not formed by a central organ plus militants, but is a tight, unified network in which all its component parts overlap and work together. The central organ should rather be seen as the nucleus of the cell which co-ordinates the metabolism of an organic entity.

In this sense the whole organisation is constantly concerned with the activities of its central organs, which have to make regular reports on their activity. Even if it is only at the Congress that they are given their mandate the central organs have to have their ears open all the time to the life of the organisation, to constantly take this life into account.

According to necessities and circumstances, the central organs can designate from amongst themselves sub-commissions which have the responsibility of carrying out the decisions adopted at the plenary meetings of central organs, as well as accomplishing any other task (notably taking up positions) which proves necessary between plenums.

These sub-commissions are responsible to the plenums. On a more general level, the relations between the organisation as a whole and its central organs is the same as that between the central organs and their permanent sub-commissions.

6. This concern for the greatest possible unity within the organisation also applies to the definition of the mechanisms which allow for the taking up of positions and the nomination of central organs. There is no ideal mechanism that will guarantee that the best choice will be made when it comes to taking positions, adopting orientations, and nominating militants for the central organs. However, voting and elections are the best way of ensuring both the unity of the organisation and the widest participation of the whole organisation in its own life.

In general decisions at all levels (Congresses, central organs, local sections) are taken on the basis of a simple majority (when there is no of unanimity). However, certain decisions, which could have a direct repercussion on the unity of the organisation (modification of platform or statutes, integration or exclusion of militants) are taken by a stronger majority than a simple one (three-fifths, three-quarters, etc).

On the other hand, still with the same concern for unity, a minority of the organisation can call for an extraordinary Congress when it becomes a significant minority (for example two-fifths). As a general rule it's up to the Congress to settle essential questions, and the existence of a strong minority demanding that a Congress be held is an indication that there are important problems in the organisation.

Finally, it's clear that the votes only have a meaning if the members who are in a minority carry out the decisions made, decisions which become those of the organisation.

In the nomination of central organs the following three elements have to be taken into account:

-

the nature of the tasks which these organs have to carry out;

-

the candidates' aptitude with regard to these tasks;

-

their capacity to work in a collective living manner.

It's in this sense that you can say that the assembly (Congress or whatever) which elects a central organ is nominating a team; this is why in general, the outgoing central organ puts forward a proposed list of candidates. However it's up to this assembly (and this is also the right of each militant) to put forward other candidates if it thinks this is necessary, and in any case it elects members to central organs on an individual basis. This is the only kind of election which allows the organisation to equip itself with organs which have its maximum confidence.

It is the responsibility of the central organs to apply and defend the decisions and orientations adopted by the Congress which elected it. In this sense it is more opportune if, within the organ, there is a strong proportion of militants who, at the Congress, pronounce themselves in favour of its decisions and orientations. This, however, doesn't mean that only those who defended majority positions at the Congress, positions which then became those of the organisation, can be part of the central organ.

The three criteria defined above remain valid whatever positions defended during the debates by this or that candidate. Neither does this mean that there must be a principle of representation - for example proportional representation - of minority positions within the central organ. This is a typical practice of bourgeois parties, notably social democratic parties whose leadership is made up of representatives of different currents or tendencies in proportion to the votes received at the Congress. Such a way of designating the central organ corresponds to the fact that in a bourgeois organisation the existence of divergences is based on the defence of this or that orientation for managing capitalism, or simply on the defence of the interests of this or that sector of the ruling class or this or that clique, orientations and interests which are maintained on a long term basis and which have to be conciliated by a 'fair' distribution of posts among their representatives. This does not apply to a communist organisation where divergences in no way express the defence of material interests, of personal interests, or those of particular groups, but express a living and dynamic process of clarification of problems posed to the class and Which, as such, can be resolved through the deepening of discussion and in the light of experience. To have a stable, permanent, and proportional representation of the different positions, which appeared on the various points on the agenda of a Congress would thus be to ignore the fact that the members of central organs:

-

have as their first responsibility the task of applying the decisions and orientations of the Congress;

-

can perfectly easily change their personal positions (in one direction or another) with the evolution of the debate.

7. We should avoid using the terms 'democratic' or 'organic' to describe the centralism of a revolutionary organisation:

-

because it takes us no further to a correct understanding of centralism;

-

because these terms are themselves bound up with the practices which they described in the past.

Today the idea of 'democratic centralism' (a term we owe to Lenin) is marked by the seal of Stalinism which used it to cover up the process by which any revolutionary life in the parties of the CI were stifled and liquidated. Moreover, Lenin himself bears some responsibility for this in that, at the Tenth congress of the Russian Communist Party (1921), he asked for and won the banning of fractions which he - wrongly, even on a provisional basis - considered to he necessary in the face of the terrible difficulties the revolution was going through. Furthermore the demand for a "real democratic centralism", as practiced in the Bolshevik party, has no sense either, in that:

-

certain conceptions defended by Lenin (notably in One Step Forward, Two Steps Back) about the hierarchical and 'military' character of the organisation, conceptions exploited by Stalinism to justify its methods, should be rejected.

-

the term 'democratic' is itself not the most appropriate, both etymologically ('power of the people') and because of the meaning it has acquired under capitalism which has turned it into a formalistic fetish used to cover up and justify the bourgeoisie's domination over society.

To a certain extent, the term 'organic' (which we owe to Bordiga) would be more correct in describing the kind of centralism that exists in an organisation of revolutionaries. However the fact that the Bordigist current has used this term to justify a mode of functioning which prevents the organisation as a whole exerting any control over its central organs and over its own life, disqualifies the term and makes it necessary for us to reject it also. For Bordigism, the fact - correct in itself - that a majority is in favour of a position doesn't guarantee that it Is correct, or that the election of central organs is not a perfect device which prevents it from any kind of degeneration, is used to defend a conception of organisation where votes and elections are banned. In this conception the correct positions and the leaders arise 'by themselves' through a so-called organic process, which in practice means giving the 'centre' the job of deciding everything and settling every debate, and leads this 'centre' to align itself behind the positions of a 'historic leader' who has a sort of divine infallibility. Since they are opposed to any kind of religious or mystical spirit, revolutionaries have no intention of replacing the pontiff of Rome with one from Naples or Milan.

Once again voting and elections, however imperfect they may be, are in present conditions still the best way of guaranteeing the maximum unity and life in the organisation.

8. Contrary to the Bordigist standpoint, the organisation of revolutionaries cannot be 'monolithic'. The existence of disagreements within it is an expression of the fact that it is a living organ which does not have fully formed answers which can be immediately applied to the problems arising in the class. Marxism is neither a dogma nor a catechism. It is the theoretical instrument of a class which through its experience and with a view towards its historic future, advances gradually, through ups and downs, towards a self-awareness which is the indispensable precondition for emancipating itself. As in all human thought, the process whereby proletarian consciousness develops is not a linear or mechanical process but a contradictory and critical one: it necessarily presupposes discussion and the confrontation of arguments. In fact, the famous 'monolithism' or 'invariance' of the Bordigists is a decoy (as can be seen in the positions taken up by the Bordigist organisations and their various sections); either the organisation is completely sclerotic and is no longer affected by the life of the class, or it's not monolithic and its positions are not invariant.

9. While the existence of divergences within the organisation is a sign that it is alive, only by respecting a certain number of rules in the discussion of these divergences can we ensure that such discussion is a real contribution to the strengthening of the organisation and to the improvement of the tasks for which the class has engendered it. We can thus enumerate certain of these rules:

-

having regular meetings of local sections, and putting on the agenda of these meetings the main questions being discussed in the organisation: in no way must this debate be stifled;

-

the widest possible circulation of different contributions within the organisation through the appropriate instruments;

-

consequently, the rejection of secret and bilateral correspondence which, far from allowing debate to be more clear, can only obscure it by giving rise to misunderstanding, distrust and a tendency towards the formation of an organisation within the organisation;

-

respect by the minority for the indispensable organisational discipline (as we saw in the last point);

-

rejection of any disciplinary or administrative measure on the part of the organisation with regard to members who raise disagreements: just as the minority must know how to be a minority inside the organisation, the majority must know how to be a majority, and in particular it must not abuse the fact that its position has become the position of the organisation and annihilate debate in any way, for example, by compelling members of the minority to be spokesmen for positions they don't adhere to;

-

the whole organisation is interested in discussion being as wide-ranging and as clear as possible (even when it deals with divergences of principle which can only lead to an organisational separation): it's up to both the minority and the majority to do all they can (obviously without this paralysing or weakening the tasks of the organisation) to convince each other of the validity of their respective analyses, or at least to allow the greatest possible clarity to emerge on the nature and significance of these disagreements.

To the extent that the debates going on in the organisation generally concern the whole proletariat they should be expressed publicly while respecting the following conditions:

-

that these debates involve general political questions and that they have matured sufficiently for their publication to be a real contribution to the developments of class consciousness;

-

the place given to these debates should not disrupt the general balance of the publications;

-

it's the organisation as a whole which decides on and carries out the publication of such contributions, basing such decisions on criteria which apply to any other article in the press: whether it's clearly written, whether it's of interest to the working class as a whole, etc. We must therefore reject the publication of texts outside of the organs responsible for publications, on the 'private' initiative of a certain number of members of the organisation. Similarly, there is no formal 'right' of anyone in the organisation (individual or tendency) to have a text published if the responsible organs don't feel that it is useful or opportune.

10. The divergences which exist within the organisation of revolutionaries can give rise to organised forms of minority positions. While, when such a process gets underway, no administrative measure (such as the banning of such organised forms) can substitute for the most thorough-going discussion, it's equally important that this process is handled in a responsible manner, which implies:

-

that this organised form of disagreements is based on a positive and coherent position, not on a heterogeneous collection of points of opposition and of recriminations;

-

that the organisation is able to understand the nature of such a process; in particular, that it is able to understand the difference between a tendency and a fraction.

A tendency is above all an expression of the life of the organisation, of the fact that thought never develops in a linear manner but through a contradictory process of discussion and of confrontation of ideas. As such, a tendency is generally destined to be reabsorbed once a question has become sufficiently clear for the whole organisation to put forward a single analysis, either as a result of discussion, or as the result of new elements which confirm one view and refute the other. Furthermore, a tendency develops essentially on points determining the orientation and intervention of the organisation. It is not constituted straight away around points of theoretical analyses. Such a conception of tendencies leads to a weakening of the organisation and a dispersal of militant energies.

A fraction is an expression of the fact that the organisation is in crisis, that a process of degeneration, of capitulation to the dominant ideology, has appeared within it. Contrary to the tendency, which emerges a around differences of orientation on circumstantial questions, the fraction is formed around programmatic differences which can only result either in the bourgeois positions being expunged from the organisation, or in the departure of the communist fraction. Since the fraction expresses a demarcation between two positions which have become incompatible within the organisation, it tends to take on an organised form with its own organs of propaganda.

It's because the organisation of the class is never guaranteed against degeneration that the role of revolutionaries is to constantly struggle against the bourgeois positions which can appear within it. And when they find themselves in a minority in this struggle their task is to organise themselves into a fraction, either to win the whole organisation to communist positions and to exclude the bourgeois positions or, when this struggle has become sterile because the organisation - generally in a period of re-flux - has abandoned the proletarian terrain to constitute a bridge towards the reforging of the class party, which can only emerge in a historic period of rising class struggle.

In all these cases the concern that must guide revolutionaries is one that is valid for the class in general: not to waste the already tiny revolutionary energies that the class possesses; to ensure at all times the maintenance and development of an instrument which is so indispensable and yet so fragile - the organisation of revolutionaries.

11. While the organisation must oppose the use of any administrative or disciplinary measures in the face of disagreements, this doesn't mean that it cannot use these means in any circumstances. On the contrary, it is indispensable that it resorts to measures such as temporary suspension or definitive exclusion when it is faced with attitudes, behaviour, or actions which constitute a danger to the existence of the organisation, to its security and its capacity to carry out its tasks. This applies to behaviour inside the organisation, in militant life, but also concerns behaviour outside the organisation incompatible with belonging to a communist organisation.

Moreover, it is important that the organisation take all the measures necessary to protect itself from attempts at infiltration or destruction by agents of the capitalist state, or by elements who, without being directly manipulated by these organs, behave in a way likely to facilitate their work. When such behaviour comes to light, it is the duty of the organisation to take measures not only in defence of its own security, but also in defence of the security of other communist organisations.

12. A fundamental precondition for a communist organisation being able to carry out its tasks in the class is a correct understanding of the relations that should exist between the organisation and its militants. This is a particularly difficult question to understand today, given the weight of the organic break with past fractions and of the influence of elements from the student milieu in the revolutionary organisations after 1968. This has allowed the reappearance of one of the ball-and-chains carried by the workers' movement in the 19th century - individualism.

In a general manner, the relations between the militants and the organisation are based on the same principles as those mentioned above concerning the relations between the parts and the whole. More precisely, the following points need to be made on this question:

-

The working class doesn't give rise to revolutionary militants but to revolutionary organisations: there is no direct relationship between the militants and the class. The militants participate in the class struggle in so far as they become members and carry out the tasks of the organisation. They have no particular 'salvation' to gain in front of the class or of history. The only 'salvation' that matters to them is that of the class and of the organisation which it has given rise to.

-

The same relations which exist between a particular organ (group or party) and the class exists between the organisation and the militant. And just as the class does not exist to respond to the needs of the communist organisation, so communist organisations don't exist to resolve the problems of the individual militant. The organisation is not the product of the needs of the militant. One is a militant to the extent that one has understood and adheres to the tasks and functions of the organisation.

-

Following on from this, the division of tasks and of responsibilities within the organisation is not aimed at the 'realisation' of individual militants. Tasks must be divided up in a way that enables the organisation as a whole to function in the optimal way. While the organisation must as much as possible look to the well-being of each of its militants, this is above all because it's in the interest of the organisation that all of its 'cells' are able to carry out their part in the organisation's work. This doesn't mean ignoring the individuality and the problems of the militant; it means that the point of departure, and the point of arrival, is the capacity of the organisation to carry out its tasks in the class struggle.

-

Within the organisation there are no 'noble' tasks and no 'secondary' or 'less noble' tasks. Both the work of theoretical elaboration and the realisation of practical tasks, both the work in central organs and the specific work of local sections, are equally important for the organisation and should not be put in a hierarchical order (it's capitalism which establishes such hierarchies). This is why we must completely reject, as a bourgeois conception, the idea that the nomination of a militant to a central organ is some kind of 'promotion', the granting of an 'honour' or a 'privilege'. The spirit of careerism must be completely banished from the organisation as being totally opposed to the disinterested dedication which is one of the main characteristics of communist militantism.

-

Although there do exist inequalities of ability between individuals and militants, and these are maintained and strengthened by class society, the role of the organisation is not, as the utopian communists thought, to pretend to abolish them. The organisation must try to ensure the maximum development of the political capacities of its militants because this is a preconditions for its own strengthening, but it never poses this in terms of an individual, scholarly formation, nor of an equalisation of everyone's formation.

The real equality between militants consists in the maximum of what they can give for the life of the orgainsation ("from each according to his means", a quote from St. Simon which Marx adopted). The true 'realisation' of a militant, as a militant, is to do all they can to help the organisation carry out the tasks for which the class has engendered it. -

All these points imply that the militant does not make a personal 'investment' in the organisation, from which he expects dividends or which he can withdraw when he leaves the organisation. We must therefore reject, as totally alien to the proletariat, any practice of 'recuperating' material or funds from the organisation, even with the aim of setting up another political group.

-

Similarly, "the relations between the militants", while they "necessarily bear the scars of capitalist society...cannot be in flagrant contradiction with the goal pursued by revolutionaries, and they must of necessity be based on that solidarity and mutual confidence which are the hallmarks of belonging to an organisation of the class which is the bearer of communism" (ICC Platform).

FOOTNOTES

1. This affirmation isn't only applicable internally; it's mot just aimed at the splits which have taken place (or may take place in the future) in the ICC. Within the proletarian political milieu, we have always defended this position. This was notably the case when the Aberdeen/Edinburgh sections split from the Communist Workers Organisation and when the Nucleo Communista Internationalista broke from Programma Communista. We criticised the hasty nature of these splits based on divergences which didn't seem to be fundamental and which weren't clarified through a rigorous internal debate. As a general rule, the ICC is opposed to unprincipled 'splits' based on secondary differences (even when the militants concerned seek to join the ICC). Any split on secondary differences is in reality the result of a monolithic conception which doesn't tolerate any discussions or divergences within the organisation. This view is typical of a sect.

Life of the ICC:

Heritage of the Communist Left:

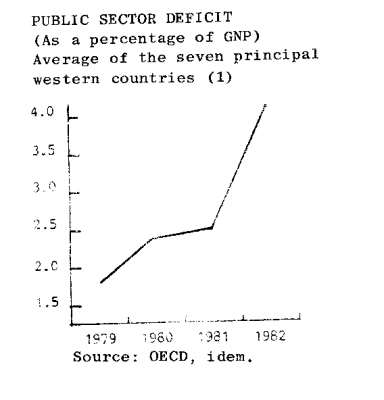

What Point Has The Crisis Reached? (2nd quarter 1983)

- 2447 reads

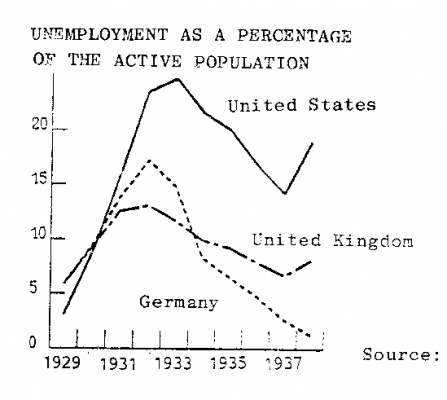

Unemployment in the 30’s

Source: A. Madisson, Economic Growth.

After a terrific acceleration which (especially in the US), gave rise to an explosive social situation, the state’s reflationary policies allowed a reduction of unemployment to below its 1932 level right up to the outbreak of war. Moreover, for a Proletariat still marked by the bloody repression of the revolution, the inauguration of unemployment and various other benefits was the trap that allowed the bourgeoisie to defuse the political bomb of a high unemployment rate in the heart of industrial capitalism.

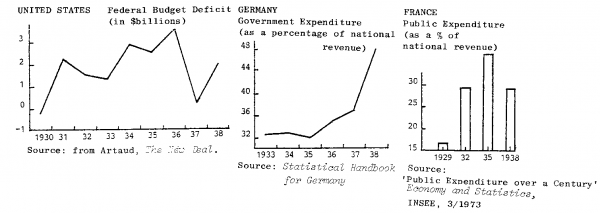

The State's Role in the Economy during the 30’s

The bourgeoisie defused the social bomb of unemployment thanks to the state’s reflationary policies, The state came to control an ever larger and more dominant part of the national economy -- whether through the war economy in Germany, the New Deal in the US, or the Popular Front’s nationalizations in France. State indebtedness made it possible to delay the effects of the reemerging crisis. This gave it enough respite to conclude successfully its policy of control over the proletariat in the war behind the illusion of the social state -- national socialist, Stalinist and, above all, the democratic welfare state.

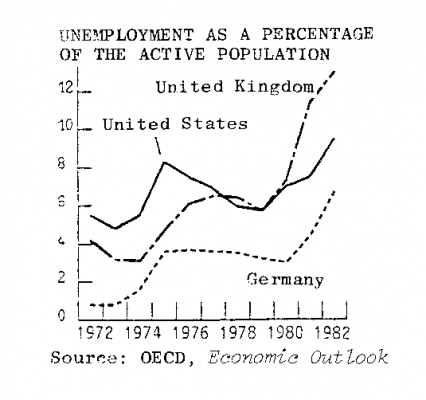

Unemployment today

Unemployment today is developing differently from that of the great crisis of the 30s. Throughout the 70s there was a slow increase. The beginning of the 80s sees an upsurge with more than 11 million unemployed in the US, 3 million in Britain, 2.5 million in West Germany -- this is the equivalent of the entire working population of Germany, Holland and Belgium put together.

From this point of view, the situation is the opposite of that in the 30s. The crisis is developing on the basis of the exhaustion (expressed in a growing ineffectiveness) of the measures that allowed the bourgeoisie to face up to the crisis of. 1929. Unemployment is developing inexorably and ever more rapidly while social assistance is diminishing. The social situation will become more and more explosive. Employment is not going to increase while investment drops.

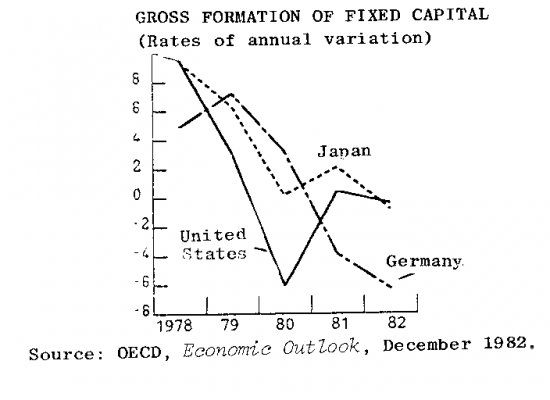

Declining Investment

The impossibility on an oversaturated market of making any profit from the sale of commodities, the rapid obsolescence and under-utilization of the productive apparatus in the face of bitter competition, pushes the bourgeoisie not only to diminish its industrial investments but also to increase its speculation on the world market, whether on the financial level or in raw materials. Moreover, most investment is concentrated in the search for greater competivity through intensive mechanization and automation -- which inevitably eliminates more jobs than it creates. Even the hypothetical reflation that we hear so much about would only accelerate this tendency. In those conditions, unemployment can only go on rising.

World Indebtedness

The policy of reflation is based on state indebtedness. During the 30s this policy was new and the state was not already heavily in debt; this is no longer the case today. The USA, which was the motive force behind the successive (but unsuccessful) reflations of the 70s, is now heavily in debt on the world market; the combined state and private debt is in the region of 5000 billion dollars. To liquidate this debt would require American workers to work for free for 1.5-2 years.

The policy of austerity which arrived to soak up some of this indebtedness is coming up against the instability of the international monetary system and the difficulty of attacking the living standards of a still combative working class. The colossal American budget deficit ($100 million in 1982, a possible estimated $200 million for the years to come) and the need to help out the Third World to avoid a financial collapse means working the IMF’s financial pump (an increase of 74% in its credits is planned) . The bourgeoisie is obliged to use its printing presses; the Reagan-Thatcher medicine is impotent against this indebtedness and the danger of a new upsurge of inflation -- which is the only “reflation” we can expect.

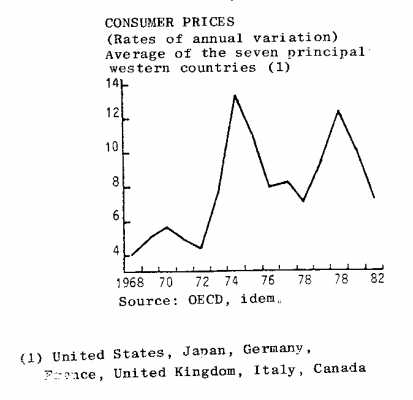

Inflation has not gone away

In order to justify the deflationary policies of the last few years, the bourgeoisie congratulates itself with having got inflation under control. However, inflation is not only still present but, more importantly, inflationary pressures are appearing more strongly despite the recession as we have seen. The policies of reflation and deflation, austerity, produce the same negative results and demonstrate the bourgeoisie’s inability to confront the crisis.

The policy of reflation renews inflation without preventing the tendency towards recession from getting the upper hand; the policy of deflation plunges the economy into the depression without preventing the development of inflationary tendencies. Despite the fall in inflation observed these last few years, the years to come will see the parallel development of growing inflation and growing unemployment. The working class should have no illusions; all the bourgeoisie’s economic policies are impotent to confront the crisis.

Recent and ongoing:

- Economic Crisis [5]

Where is The Class Struggle Going? Towards the end of the post-Poland retreat

- 2586 reads

"Proletarian revolutions, like those of the nineteenth century, criticize themselves constantly, interrupt themselves continually in their own course, come back to the apparently accomplished in order to begin it afresh, deride with unmerciful thoroughness the inadequacies, weaknesses and paltrinesses of their first attempts, seem to throw down their adversary only in order that he may draw new strength from the earth and rise again, more gigantic, before them, recoil ever and anon from the indefinite prodigiousness of their own aims, until a situation has been created which makes all turning back impossible, and the conditions themselves cry out; Hic Rhodus, hic saltar!"[1]

The years of truth, the 1980s, began with a major explosion of the class struggle. The August 1980 mass strike in Poland, clashing with enormous force against the state, showed that the open struggle between the proletariat and the ruling class had become, and would more and more become, the basic characteristic of the coming period. However, the Polish workers found themselves isolated. Between 1980 and 1982 the number of workers' struggles, in particular in the most industrialized countries, has tended to diminish more and more. How are we to understand this retreat at precisely the time when the world crisis of capitalism is visibly accelerating? What is the perspective for the class struggle?

1968-1982: 15 years of economic crisis and workers' struggles

The proletarian struggle can only be understood by seeing it in its world-wide, historical dimension: it's not a mosaic of national movements with no past or future. In order to grasp the present movement of the world class struggle we must first of all situate it in its historic context, in particular that of the general movement which began with the breakthrough in 1968.

By understanding the dynamic of the relationship between the classes in these years of the open economic crisis of decadent capitalism, we can draw out perspectives for the class struggle.

1968-1982: Fifteen years of economic crisis and workers' struggles

Concerning this balance of forces between the proletariat and the bourgeoisie, we can broadly speaking distinguish four phases within the 1968-82 period[2]:

1968-74: development of the class struggle

1975-78: reflux, counter-offensive of the bourgeoisie

1978-80: revival of struggle

1980-82: reflux, counter-offensive

1968-74: The break with half a century of triumphant counter-revolution

The thunderbolt of a ten-million strong strike in France in May-June 1968 opened up a period of proletarian struggles which marked a clear break with 50 years of counter-revolution. Since the mid-‘20s, the workers of the entire world had carried the scars of the crushing of the revolutionary wave that broke out at the end of the First World War, Stalinism, fascism, anti-Stalinism, anti-fascism, the ideology of national liberation movements, bourgeois democracy -- all this had kept the workers in a state of atomization, of material and ideological subordination, and even of mobilization behind the flags of different national capitals.

On the eve of 1968, ‘fashionable' thinkers were theorizing the ‘disappearance of the working class' into ‘embourgeoisification' and the so-called ‘consumer society'.

The 1968-75 wave of struggles which, in varying degrees, hit virtually all countries (both developed and under-developed) was in itself a striking rebuttal of all theorizations about ‘eternal social peace'. And this was by no means its least achievement. From Paris to Cordoba in Argentina, from Gdansk to Detroit, from Shanghai to Lisbon, 1968-75 was the workers' response to the first shocks of the world economic crisis, which capitalism was now sinking into after completing twenty years of post-war reconstruction.

This first great period of struggle posed right away all the problems the proletariat was going to come up against in future years: encapsulation by the unions and the so-called ‘workers' parties', illusions in the possibilities of a new prosperity for capitalism or the mechanisms of bourgeois democracy, the national vision of the reality of the class struggle. In short, the difficulty of developing working class autonomy and self-organization against the political forces of the bourgeois state.

But generally speaking, these confrontations did not represent a break with the illusions of a period when the reality of the economic crisis was only just coming to the surface.

For twenty years capitalism had been through a period of relative economic stability. The idea that it was possible to go back to this situation was still predominant, all the more so because in 1972-73 western capitalism was able to come out of the 1970-71 recession by ridding itself of the constraints of a fixed rate of exchange and of convertibility of the dollar. This gave rise to an unprecedented burst of ‘growth'.

Between 1968 and 1974, unemployment grew noticably in many western countries, but it was still at a relatively low level[3]. The attacks suffered by the working class in this period took place mainly at the level of consumer prices[4].

Faced with the rising class struggle, the left forces of the bourgeoisie were able to radicalize their language and readapt their structures in order to, in one way or another, keep control of the struggles. The example of the Italian unions during the ‘hot autumn' of 1969 is perhaps one of the most significant and spectacular examples of this: after being violently contested by assemblies of workers in struggle, they responded by setting up ‘factory councils' composed of delegates from the base, in order to reassert their power in the factories.

This was to prove insufficient as the economic crisis picked up speed again in ‘74-‘75 the bourgeoisie had to impose new sacrifices on the exploited class,, Starting from the still-powerful illusion of a ‘return to prosperity' (an illusion which still captivated the bourgeoisie itself), it successfully developed the perspective of the ‘left in power'.

Through this first wave of struggles the world proletariat marked its return to the centre-stage of history. But the evolution of the objective situation didn't allow the revolutionary class understand the overall perspective and resolve the problems posed by the struggle.

1975-78: The counter-offensive of the bourgeoisie. The Left in power

The 1974-75 recession, which the press called the ‘oil crisis', marked the beginning of the real effects of the crisis. It brought about profound changes in social life. Restrictions on working class living standards became more and more noticeable. Unemployment rose irreversibly in Europe and, while it diminished momentarily in the USA, it still remained at a high level.

Using the pretext of energy shortages, the bourgeoisie starting talking about restrictions, sacrifices, austerity. It cultivated the illusion that if the crisis was managed by the political parties of the left, by parties ‘close to the workers', the workers' sacrifices would be put to proper use and inequalities would be reduced.

In 1976, left parties had already formed governments in the USA, in Britain, in Germany. In France the left had a growing number of electoral victories and developed the theme ‘no strikes -- otherwise we will frighten the population and prevent the victory of the left'. In Italy, after a number of electoral triumphs, the Italian Communist Party had a share in power through the ‘historic compromise' with the Christian Democrat government. In most countries, the number of strikes went down. Reality, however, began to undermine the old illusions. The economic crisis got deeper and deeper. The electoral victories of the left parties changed nothing. Calls for sacrifices increased, even though it was becoming more and more obvious that they had no effect.

By 1978, the signs already indicated that this period of reflux was over.

1978-80: The second wave of struggles: Poland

At the beginning of 1981, we wrote about this "second wave ... led ... by the American miners in 1978, the French steelworkers at the start of 1979, the Rotterdam dockworkers in autumn ‘79, the British steelworkers at the start of 1980, as well as the Brazilian metalworkers throughout this period. The present movement of the Polish proletariat belongs to this second wave of struggles." (The International Dimension of the Workers' Struggle in Poland, IR 24)

The workers' struggles which preceded the ones in Poland were less numerous than those in 1968-74. But when one looks at them as a whole it becomes clear that they summarized in just over a year the essential experiences of the first wave of struggles.

By confronting or even overflowing the unions, like the US miners, by creating in the struggle a form of self-organization independent of the unions, as with the Rotterdam port workers, by trying to take the struggle to the centers of power and to the main concentrations of the class, like the French steelworkers with their ‘march on Paris', by making solidarity the key to their fight like the British steelworkers with their flying pickets; all these battles took up many of the problems of the struggle at the level they had been left at by the clashes in the first wave.

The mass strike in Poland brought practical answers to many of these problems. The mass strike showed the capacity of the proletariat to unite, to fight without regard to differences of category or sector. It demonstrated the workers' capacity for self-organization by creating assemblies and committees of delegates on a scale never reached during the first wave. Above all, it illustrated concretely how by unifying, generalizing and organizing its struggles the proletariat could form itself into a power capable of standing up to and even pushing back the most totalitarian of governments.

But by developing this force, by throwing the national government (and with it the entire Russian military bloc) into disarray, the proletariat found itself at a higher level of confrontation with the state. Not since the 192Os had the working class imposed such a political balance of forces on the bourgeoisie.

The struggles in Poland showed clearly that when the confrontation between the classes has reached this level, things no longer operate at a purely national level. The bourgeoisie confronted the Polish proletariat with all the economic, military and ideological forces it possesses on an international scale. Even if the workers weren't always aware of this, they were still faced head-on with the real consequences of their own power: if they were to, in their turn, answer the bourgeoisie's riposte, if they were going to take their struggle forward -- the only alternative to retreating -- they would have to proceed to the international generalization of the proletarian struggle.

This generalization was indispensable not only for the obvious military and economic reasons but above all because it was a precondition for the development of the consciousness of the Polish workers themselves.