Manifesto on the ecological crisis

- 447 reads

A newly-published Manifesto looking at various aspects of the worsening ecological crisis, their root causes, capitalism's inability to do anything but make matters worse and the only solution available to humanity - the communist revolution: what it is, what it is not and which social force can enact it.

Rubric:

1) Is it possible to stop the destruction of the planet?

- 260 reads

The state of the planet is catastrophic. The climate is warming faster than any scientific forecast, causing fires, droughts, storms, floods... The oceans are acidifying, and with them the rainfall; vegetation under water or on land is suffering the disastrous consequences. Worldwide deforestation is breaking records every year, and asphalt is covering more and more land. Pollution contaminates everything: greenhouse gases, pesticides in the soil, plastic particles in the seas, pharmaceutical molecules in rivers.... to the point where fish doped with oestrogen are changing sex!

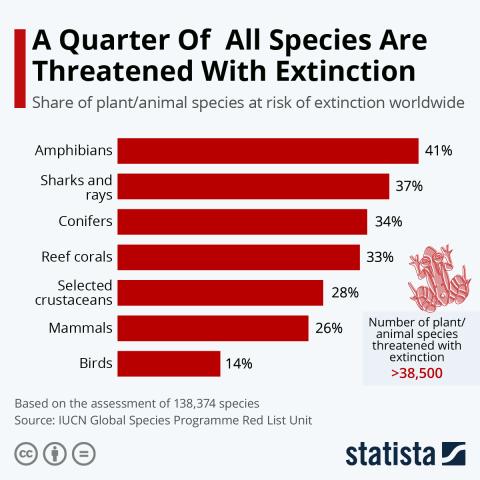

The direct consequence of human activity is devastating: 26,000 species disappear every year. More and more researchers are anticipating the sixth wave of mass extinction (the previous one, the fifth, being that of the dinosaurs, 66 million years ago). “If bees disappeared from the face of the earth, man would only have four years to live”. Although Einstein never actually uttered this sentence, the powerful idea is nonetheless true: insects feed the world (birds, reptiles, mammals, plants) and pollinate 75% of crops and 80% of wild plants. Their gradual disappearance is a direct threat to natural ecosystems and humanity's ability to feed itself.

The human species is already suffering massively from this destruction of the planet. Every year, ‘natural’ disasters linked to global warming force tens of millions of people into exile; air pollution causes millions of ‘premature’ deaths, and over two billion human beings are tortured by a lack of water. The Covid 19 pandemic, which according to the World Health Organisation killed 7 million people between 2019 and 2021 (15.9 million according to demographers), and which has reduced global life expectancy by a year and a half, is also partly to the ecological crisis. This pandemic has highlighted the link between the destruction of nature and the threat to human health. According to the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES), 70% of emerging diseases (Zika, Ebola, Nipah, etc.) and almost all known pandemics (e.g. influenza, HIV, Covid-19) originate from zoonoses (diseases caused by infections of animal origin). The underlying causes of these pandemics are the same as those that ravage nature: deforestation and destruction of natural ecosystems, trade in and consumption of wild species, etc.

In 2009, an international team of twenty-eight researchers led by Johan Rockström, a world-renowned Swedish scientist, established nine ‘planetary limits’ that humanity should not exceed if it is not to compromise the conditions for its survival:

1. Climate change

2. Erosion of biodiversity

3. Disruption of the biogeochemical cycles of nitrogen and phosphorus

4. Changes in land use

5. Ocean acidification.

6. Global water use

7. Depletion of the ozone laye.

8. The introduction of new entities into the environment (heavy metals, synthetic and radioactive compounds…)

9. And the concentration of aerosols in the atmosphere.

Six of these nine “planetary limits” have already been exceeded (and two of them cannot be measured). The scale of the disaster underway is such that the Davos Forum itself is forced to acknowledge that "The loss of biodiversity and the collapse of ecosystems is considered to be one of the most rapidly deteriorating global risks of the next decade (...) The combination of extreme weather events and limited supplies could transform the current cost of living crisis into a catastrophic scenario of hunger and distress for millions of people (...).The interaction between the effects of climate change, biodiversity loss, food security and the consumption of natural resources will accelerate the collapse of ecosystems”.

It is not life on earth as such that is at stake. It has already been able to develop in much more hostile conditions, to recover after waves of mass extinction that were even more extensive than today; life can be found at the bottom of the oceans, under the earth, on every surface. No, what is threatened is the human species. The way society works today will eventually make the earth uninhabitable for humanity.

All the ‘solutions’ to the ecological crisis proposed by the ruling class are futile because the problems we face are built into the global system that dominates the planet –the capitalist system, which lives through exploitation and the hunt for profit. Exploitation of human labour power through the wage relation; exploitation of nature, which it regards as a free gift to be plundered at will. And although capitalism has produced the scientific and technological means which could be used to free humanity from poverty and alienated labour, the clash between this productive potential and the very motivation for production has become permanent. Capitalism has been an obsolete, decadent form of society for over a hundred years. This long decline has now reached a terminal phase, a dead-end in which war, crises of overproduction and ecological destruction have reached the point at which all these manifestations of the impasse are acting on each other to produce a terrible whirlwind of destruction. But there is an alternative to the nightmare being realised by capitalism: the international struggle of the exploited class for the overthrow of capitalism and the construction of a world communist society.

2) The ravages of war

- 148 reads

Picture: Kuwait, 1991

Since 1914, war has become a permanent feature on all continents. Two hundred conflicts, two hundred million deaths, two cities flattened by atomic bombs! Napalm, chemical and bacteriological weapons, cluster bombs, killer drones... the latest technology at the service of barbarity.

The twentieth century has been repeatedly named the most barbaric century in the history of mankind. But the 21st century is well on the way to figure even higher in the annals of horror, having opened with the Twin Towers attacks on 11 September. Since then, the chaos has spread from region to region: Iraq, Afghanistan, Syria, Libya, Congo, Ukraine, Israel/Palestine... and perhaps tomorrow Taiwan.

War has become so much the centre of gravity of the whole of society that it focuses all scientific research on it. Microwaves, freeze-dried products, tins of food, self-injecting syringes, GPS, aviator sunglasses, the Internet... the list of objects produced by military research is endless. The First World War gave rise to a permanent war economy: in a fierce struggle, governments had to focus their industry and scientific research on this area of destruction and death. Since then it has been war that structures society.

Today, worldwide military spending exceeds 2400 billion dollars a year. This figure is rising steadily and will be even higher tomorrow!

War takes the lives of millions of people. But it also annihilates all other forms of life. Battlefields are desolate wastelands; flora and fauna are wiped out.

Each war causes an environmental disaster that lasts for centuries: heavy metals, chemicals and radioactive elements remain for centuries, even millenia. The consequences of the First World War are still being felt today. Lead and mercury from the degradation of munitions contaminate groundwater wherever there were trenches. In France, because of the shells buried in the soil, 120,000 hectares of battlefield are still unfit for any human activity! During the Vietnam War in the 1960s, the US army deliberately used an ultra-toxic herbicide (“Agent Orange”) to destroy vegetation and make it easier to spot Viet Cong forces. As a result, this chemical destroyed all the forests in 20% of the south of the country and continues to contaminate the environment and population! And what about nuclear power? All the nuclear-equipped states are carrying out tests that are causing a considerable increase in cancer in all the ‘local’ populations. 2,000 official nuclear tests to be precise.

The conflict in Ukraine is a concentration of all these destructive forces. In addition to the hundreds of thousands of deaths on both sides, the risk of the Zaporizhzha power station going off the rails is making the world tremble; collapsed buildings everywhere are releasing incalculable quantities of asbestos into the air; abandoned tanks, weapons and medical equipment represent tonnes of highly polluting waste. Just one figure: while the country contains 35% of Europe's flora and fauna, almost 30% of the country's forests have already been destroyed.

In Ukraine, environmental destruction is a weapon of war. The explosion of the Kakhovka dam on 6 June 2023 is proof of this: thousands of hectares of farmland and nature reserves destroyed, industrial sites flooded, causing the water from the dam to mix with various chemicals, hydrocarbons and waste water, and so on. The devastation of Gaza by the Israeli miliary is having similar effects on the environment as it massacres and starves the population in tens of thousands. Today's wars show that this scorched earth strategy has been reinforced: destroying the resources of an environment in order to starve its adversary. This was also one of the objectives of using napalm in Vietnam.

And to complete the circle, all the colossal military spending to come will even lead governments to abandon their minimum commitments to the climate: drastic cuts in programmes to reduce CO2 emissions, in research into alternative energies, and so on.

This is the world as it has been since 1914, a world at permanent war that is gobbling up resources and burning up entire regions. If nothing is done to stop this dynamic, states will continue their killing spree, and the hotbeds of war will spread until they consume everything.

3) Faced with the ecological crisis..... Can capitalist states change their spots?

- 169 reads

In 1972, the Earth Summit, the first major international conference on the environment, was held in Stockholm, Sweden. Under the aegis of the United Nations, the 113 states present made a commitment to combat pollution. A declaration of 26 principles, an action plan with 109 recommendations and the creation of the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) were adopted.

In 1992, at the third Earth Summit, international measures in favour of the environment were strengthened: ‘protecting the planet’ was now officially considered essential ‘for the future of mankind’. 196 states ratified the Convention, which required them to meet every year to ‘maintain their efforts’. These major annual meetings are known as the Conferences of the Parties (COP). The first conference, known as COP 1, was held in Berlin in 1995.

At the same time, from 1988 onwards, the same 196 States, the United Nations and the World Meteorological Organisation (WMO) formed an Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). Each new report made the headlines, and scientists systematically chose strong words to warn of the seriousness of the situation. The first report, published in 1990, stated: “Our calculations show with certainty that CO2 is responsible for more than half of the increase in the Earth's greenhouse effect (...). In the business-as-usual scenario, we predict an increase of +0.3° per decade in the average global temperature (...); this is an increase in average temperature that has never been seen before in the last 10,000 years”.

In reality, each year that passes will be worse than the forecasts, each IPCC report will underline this seriousness in an increasingly alarming way and each time all the states will announce new measures.

It has to be said that this is a real problem for every country in the world: the impact of global warming is causing a considerable increase in natural disasters, at an increasingly astronomical economic cost. Over the last 20 years, financial losses caused by extreme weather conditions have tripled, reaching €2,521 billion. More broadly, these disasters destabilise entire regions, destroying the economic fabric and driving entire populations into exile. Pollution peaks are paralysing a growing number of megacities, forcing travel restrictions. By 2050, some 300 million people will be threatened by rising sea levels.

So what have all these observations, measures and promises been leading to for over fifty years?

Let's take a particularly significant concrete example. The Arctic is being hit harder by global warming than the rest of the world. The consequences are obviously dramatic for the whole planet. Armed with their charters, international summits and promises, governments see this catastrophe as an opportunity to... exploit the region! In 2007, Russia planted a flag at the North Pole at a depth of 4,000 metres to mark its control over the region. Hydrocarbons in Siberia and North America, natural gas, oil, uranium in the Arctic, passage through the Canadian archipelagos, passage via the coasts of Russia and Scandinavia... all these new possibilities are attracting covetous schemes. And here, as elsewhere, they are competing with weapons at the ready: NATO military exercises, reinforcement of US armed bases in Iceland and Greenland, Russian naval manoeuvres...

The same logic applies to everything else: the widespread use of electric cars heralds clashes over cobalt, nickel, etc. These precious metal mines located in the countries of the South (Morocco, Chile, Argentina, etc.) are gobbling up all the water that remains, threatening local populations with drought and thirst. This is the stark reality. States will not stop exploiting humanity and the planet's resources; they will not stop destroying and impoverishing, because they embody the interests of each national bourgeoisie. The function of states is to concentrate the economic and military forces of each country for battle in the international arena. They are the highest authority in the world capitalist system, which lives only for profit and through competition. Whether or not they are aware of the danger to humanity that all their destruction represents, they will never stop.

The COPs (soon to be 30!) are nothing more than a gathering of brigands. The League of Nations, the UN, NATO, the WTO, the IMF... all these international organisations are nothing but places of confrontation and influence. Each COP is an opportunity for some to try to set new standards and constraints in order to put obstacles in the way of others: France against German or Chinese coal, the UK against French nuclear power, Germany against American oil, etc. The proliferation of wars, which in the long term threaten to kill all humanity, is the ultimate proof that states are not the solution, but the problem. And it doesn't matter which regime is in power, or the colour of the government. Whether it's a democrat or a dictator, whether it's the far right, the centre or the far left that rules this or that nation, capitalism leads everywhere to the same catastrophe. In every country, the ‘ecology’ parties are very often the most war-mongering. What a symbol!

Can citizen's movements change the world?

The scale of the ecological disaster is of concern to a growing proportion of the world's population, particularly young people. In the face of disaster, all kinds of citizen action are emerging.

On a daily basis, everyone is being called on to make an effort: sorting waste, reducing meat consumption, encouraging cycling... These small individual gestures are supposed to add up like small streams making big rivers. Every country in the world encourages this ‘civic-mindedness’: advertising, logos, incentives for electric cars, tax reductions for insulation... The eco-citizen gesture as a remedy for pollution. The same governments that are dropping bombs and razing forests want us to believe that the solution for the planet lies in individual action labelled ‘reasonable and sustainable’. Let's not be fooled: their real aim is to divide and fragment. These injunctions to ‘do the right thing for the planet’ are even intended to make those who are the victims of this system of exploitation feel guilty. At the same time, they try to make us believe that capitalism can be green, eco-responsible, sustainable... if everyone does their bit. These lies distract us from the real roots, the real causes of the ecological crisis: capitalism as such.

The same applies to the ‘Climate Marches’. These giant demonstrations regularly bring together hundreds of thousands of people around the world, deeply concerned about the future that lies ahead. Their slogans sometimes a reflect a feeling that there needs to be a profound change: “system change, not climate change”. But any effort to get to the real roots of the problem is undermined by other slogans, such as “stop the talk, start the action”, and above all by their general practice. The figurehead of this movement, the young Greta Thunberg, often says: “We want politicians to talk to scientists, to listen to them at last”. In other words, these demonstrators hope to ‘put pressure’ on leaders, to encourage them to pursue policies that are more respectful of nature. Another destructive idea stems from this logic, that of classifying older generations as ‘unconscious’ or ‘selfish’, as opposed to ‘young people’ who are fighting for the planet: “You say you love your children. You say you love your children, but you're stealing their future right out from under them,” says Greta Thunberg. So there's a whole theorisation of a supposed opposition between the ‘climate generation’ and the ‘boomers’!

‘Radical ecology’ claims to go further than that: it's no longer a question of shouting ‘Look!’ or ‘Wake up!’ at the world's powerful, but of forcing them to adopt a different policy. Extinction Rebellion (XR), and now Just Stop Oil, with their days of ‘international rebellion’, are the main representatives of this movement, which vehemently denounces the ‘ongoing ecocide’. Demonstrations, occupying road junctions, climbing on top of trains, staging stunts to publicise the disastrous state of the world's ecology... the most spectacular means are used to ‘put the pressure on’. But behind this ‘radicalism’ lies exactly the same approach: to make people believe that the state can (if it is ‘forced’ to) pursue an ecological policy, that capitalism can be ‘green’.

Within this movement in favour of direct action, one of the most active currents is the ‘zadist’ movement in France. This involves occupying ‘Zones To Defend’ (ZADs) threatened by the appetites of capital and finance, such as an area earmarked for a new airport or a mega-pond. Gatherings of ‘rebels’, the ZADs, fight against big capital to promote small-scale farming, ‘local production and consumption’, the ‘community’... in other words... small capital! So the system remains fundamentally the same, with all that that implies in terms of market exchanges and social relations.

Finally, there is a more theoretical movement that claims to want to replace capitalism with a different system, in particular the ‘degrowth’ movement. This trend points to the impossibility of green capitalism and invokes the need for ‘post-capitalism’ (Jason Hickel), ‘ecosocialism’ (John Bellamy Foster), or even ‘degrowth communism’ (Kohei Saito). This current affirms that capitalism is driven by the constant need to expand, to accumulate value, and that it can only treat nature as a ‘free gift’ to be exploited to the maximum while it seeks to subject every region of the planet to the laws of the market. But how can we achieve this different society? Through what struggles? And the degrowthers answer: a social movement ‘from below’, setting up ‘common spaces’, ‘citizens’ assemblies’... But who are the ‘citizens’ in question? What specific social force can wage the struggle for the overthrow of capitalism and put itself at the head of such a movement? This is the central question which the adepts of ‘degrowth’ don’t answer, all the better to exclude the working class from the equation, to dilute it into the ‘people’, the citizens’, etc.

To sum up: all these forms of environmental movement, from individual action to ‘radical’ protest, have in common the fact that they are doomed to impotence:

- either because they don’t attack the causes of the environmental crisis but only its consequences:

- or because they imagine that the existing states can take charge of the only change that can put an end to the ecological catastrophe: the overthrow of the capitalist system, which these same states are entirely dedicated to defending;

- or, when they claim to be in favour of overthrowing capitalism, because they are incapable of identifying the only force in society which can put an end to this system, the principal exploited class in this society, the proletariat

These movements want to be ‘radical’, but being ‘radical’ means attacking things at their roots. And the root of the environmental crisis is capitalism!

Green capitalism cannot exist

"It was a sunny summer day. It happened sometimes, even in Coketown. Seen from a distance in this weather, Coketown appeared to be shrouded in a haze inaccessible to the sun's rays. You only knew that the town was there, because you knew that the sullen blot on the landscape could only be a town. A fog of soot and smoke that veered confusedly from one side to the other, sometimes rising towards the vault of the sky, sometimes moving darkly along the ground, depending on whether the wind was rising or dying down or changing direction, a compact, shapeless tangle, pierced by sheets of oblique light that revealed only large black masses: - Coketown, seen from afar, evoked itself even though none of its bricks could be distinguished." Thus, in 1854, in his famous novel Hard Times, Charles Dickens evoked the sooty skies of Coketown, a fictional town that mirrors Manchester, where you can only see “the monstrous snakes of smoke” that trail over the town.

Humanity has always transformed nature. Even before Homo Sapiens, the first hominids used tools; some found in Ethiopia date back more than 3.4 million years. Over the course of its evolution, its technical progress and the expansion of its social organisation, humanity has developed an ever-greater capacity to act on its environment, to adapt nature to its needs. At 147 metres high and 4,500 years old, the Khufu Pyramid in Egypt bears witness to this power already acquired in Antiquity.

But at the same time, in particular with the division of society into classes, this capacity to act on the environment was accompanied by a growing estrangement from nature and the first ecological disasters: “Let us not flatter ourselves too much with our victories over nature. She takes revenge on us for every one of them. Every victory certainly has in the first place the consequences we expected, but in the second and third place it has quite different, unforeseen effects, which all too often destroy these first consequences. The people who, in Mesopotamia, Greece, Asia Minor and other places, cleared the forests to gain arable land, were far from expecting to lay the foundations for the present desolation of these countries, by destroying with the forests the centres of accumulation and conservation of humidity….” (Engels, The Role of Labour in the Transition from Ape to Man).

But prior to capitalism and its insatiable need to expand, these ecological problems were limited and local in scope. After millennia of slow evolution, capitalism increased these productive forces tenfold in just a few decades. First in Europe, then on all the other continents, it spread everywhere, transforming nature and human beings to keep its workshops, factories and plants running. However, in capitalism, the aim of production is not to satisfy human needs but to make a profit. To produce in order to sell, to sell in order to make a profit, to make a profit in order to reinvest in workers and machines... to produce more, to produce faster, to produce cheaper... to be able to continue selling in the face of fierce competition from other capitalists. This is the fundamental reason why, in 1854, Charles Dickens poetically described the cloud of black smoke that was already covering Manchester.

In those days, capitalism was in its rising, expansive phase. The drive to spread across the globe, to find new markets to overcome its regular crises of overproduction, had a progressive dimension in that it was laying the foundations for a truly global community. But the outbreak of the First World War demonstrated that this period had come to an end, and revolutionaries like Rosa Luxemburg were already insisting that the alternative was now “socialism or barbarism”. The international wave of revolutions which began in Russia in 1917 contained the promise of socialism. But the revolution was everywhere defeated and from the mid-1920s onwards it was barbarism that gained the upper hand – expressed not only in increasingly devastating imperialist wars but also in the accelerating destruction of nature, above all after the Second World War and even more so in the last few decades.

There can be no green capitalism. All the rhetoric from the bourgeoisie, from its far right to its far left, claiming to be able to ‘regulate’, ‘supervise’, ‘reform’ capitalism so that a ‘green economy’ can develop, is an outright lie. No law, no charter, no public pressure can take away capitalism's raison d'être: to exploit people and nature in order to produce, sell and make a profit. And too bad if people and nature die as a result. Written nearly 160 years ago, Karl Marx's words in the first volume of Capital seem to have been written today: “In agriculture as in manufacturing, the capitalist transformation of production seems to be nothing but the martyrdom of the producer (...). In modern agriculture, as in urban industry, the increase in productivity and the higher output of labour are bought at the price of the destruction and exhaustion of labour power. Moreover, every advance in capitalist agriculture is an advance not only in the art of robbing the worker, but also in the art of robbing the soil…”

This system of exploitation will not stop plundering natural resources and poisoning the Earth. The only solution is to overthrow capitalism. But what other system is there?

4) Communism is the only solution to the ecological crisis

- 144 reads

Because it is a society without classes and exploitation, without nations or wars, communism is the only real solution to the ecological crisis.

What communism is not

‘What? Communism? The USSR? That monstrosity?’ The Stalinist regime was indeed an abomination. Workers were exploited to the hilt, all opposition was ferociously repressed, and militarisation was at its height. As for nature, ‘Soviet’ productivism meant destruction, pollution and pillage. But communism has absolutely nothing to do with the Stalinist regimes! Yesterday in the USSR and Eastern Europe, today in China, North Korea and Cuba, there is not an ounce of communism there. Stalinism is not the continuation of the proletarian revolution of October 1917, it is its gravedigger.

While in every country 14-18 meant carnage in the trenches and disaster in the rear, the Russian proletariat refused to be sacrificed and threw itself into the fight for the world communist revolution. This revolutionary momentum soon spread to Europe. Faced with this threat to its domination, the bourgeoisie halted the war. But this was not enough. At the end of 1918, the German proletariat launched a revolution of its own. This uprising by a decisive battalion of the international proletariat was mercilessly crushed by the German bourgeois state (led by the Social Democrats!). Tens of thousands of insurgent workers were murdered, including Rosa Luxemburg, who was shot in the head at point-blank range and then thrown into a canal. This defeat broke the revolutionary wave. The Russian proletariat found itself isolated. In Russia, the counter-revolution took a turn that was as barbaric as it was Machiavellian: the Stalinist regime used the phrases of revolution, of Marx and Lenin, as a pretext to massacre or deport 80% of the Bolsheviks who had taken part in the revolution, in order to impose the most ferocious exploitation on the working class. The red that coloured the flag of Stalin and the USSR is not that of communism but of the blood of the workers!

Contrary to all the bourgeois lies that have been spread for over a hundred years, Stalinism is not the product of the October Revolution but the natural son of decadent capitalism and bourgeois counter-revolution.

Having made this necessary clarification, let us return to our initial question: what is the relationship between communism and nature? In what way is communism the “true resolution of the conflict between man and nature” (Karl Marx, 1844 Manuscripts)?

Communism is... the end of exploitation and pillage

Capitalism is exploitation.

Capitalism draws its wealth from two sources: the exploitation of nature and the exploitation of the labour power of the proletariat, both transformed into commodities. This why capitalism has no solution to the ecological crisis. It can only exploit both to the point of exhaustion and destruction. This is why the social question and the ecological question go hand in hand and can only be solved at the same time – solved by the proletariat, the only class which has an interest in abolishing all forms of exploitation.

Exploitation of the proletariat by the bourgeoisie, of man by man. Workers are forced to sell their labour power in order to live: they no longer belong to themselves; their exploited bodies are transformed into tools.

These social relations of production leave their mark on all human relations. The domination of the boss over the workers is reflected in the family between the husband and ‘his’ wife, between the father and ‘his’ children, in society between whites and blacks, men and women, the able-bodied and the disabled... Humanity's relationship with nature is not spared. Capitalists see nothing around them but resources to be exploited: ‘human resources’, ‘natural resources’. Humankind, life, nature, the planet and even the universe are reduced to the status of things, property, commodities.

Chickens in battery cages, cattle tortured in slaughterhouses... the barbarity inflicted on the animal world stems from this relationship of exploitation between humans themselves.

Because communism is the end of the exploitation of man by man, it is also the end of these relationships of domination that run through all our social relationships, just as it is the end of this relationship of predation and plundering of nature. ...

The end of the profit motive

Capitalism is the pursuit of profit.

This is the sole purpose of production under capitalism. Human beings, life, nature... nothing has any value for capitalism other than exchange value. Science itself is treated as a mere appendage of profit.

And here again this scourge indicates what communism should be: a society in which the aim of work is not the pursuit of profit, not the sale of commodities. In communism, on the contrary, all production will be for use, for need, and not for sale on the market. The activity of the associated producers, freed from wage slavery, will seek to satisfy humanity's deepest needs and desires. And feeling linked to nature, responsible for its future, will be an integral part of these needs and desires.

The end of private property

Capitalism means private property.

The appropriation of the vast majority of social wealth by a small minority is what the bourgeoisie calls ‘private property’. This is what the revolutionary working class wants to abolish.

The Stalinist regimes based their lie of being socialist societies precisely on the belief that they had abolished individual property, by concentrating all wealth in the hands of the state. In reality, whether the bourgeoisie appropriates the labour of the working class and the whole population individually or collectively, as employers or as the state, the same relations of production remain,.

In capitalism, private property is not only the right to deprive others of their property, it is also the right to own property over others and over nature. The end of private property in communism is therefore also the end of the right to possess nature: “When society has arrived at a higher degree of economic organisation, the right of ownership of a few individuals over the lands that make up the globe will seem as absurd as the right of ownership of one man over another seems insane. Neither one nation nor all the nations covering the globe are owners of the earth; they are merely its possessors, its usufructuaries, obliged to pass it on in an improved form to future generations” (Marx, Capital, Volume 3).

The end of competition of each against all

Capitalism means competition.

Between individuals, between companies, between nations. Nothing and no-one is spared. Physical exercise and play have become commercialised and nationalised sports, in which the glory of the club or the country is at stake, even if it means doping up and destroying the athletes. Schools are driven by a race for grades, where every child is assessed, compared and sorted. Religion, skin colour, custom... everything is a pretext for pitting one against the other. The workers don’t escape from this competition. They are called upon to do more than the company in the same sector, to do more than their colleagues. By extension, nature also becomes an adversary to be dominated. Even in the face of the ecological crisis, this relationship with the world comes to the fore: for all the world's leaders, it's all about ‘winning the climate battle’.

Capitalism is the reign of competition and domination; communism will be the reign of mutual aid and sharing. This relationship between people also changes the relationship with nature: “we do not rule over nature as a conqueror rules over a foreign people, as someone who is outside nature, but we belong to it with our flesh, our blood, our brains, we are in its bosom, (...) men (...) will once again know that they are one with nature and (...), this absurd and unnatural idea of an opposition between (...) man and nature will become impossible. " (Engels, The Role of Labour in the Transition from Ape to Man). ...

The end of nation states…

As authentic communists have always insisted, communist society cannot exist in one country, still less in isolated communes, but only on a world wide-scale. The ecological crisis is a direct product of capitalism’s insatiable drive to conquer the Earth under the flag of profit, to commodify the whole of nature. Already recognised in the Communist Manifesto of 1848, this drive has, in the final stages of capitalism’s historical decadence, poisoned the entire planet; and this, hand in hand with the threat of war, constitutes a direct menace to the survival of humanity and countless other species. Hence the solution to this crisis can only be envisaged on a planetary scale, through the dismantling of all nation states and the elimination of national borders

….and their devastating wars

Capitalism is war.

The competition of each against all that underpins this system leads to the confrontation between nations, to war and genocide. Since the beginning of the 20th century, all wars are imperialist wars, founded on the battle between nation states to expand their spheres of influence and control at the expense of their rivals. Ferocious military competition has become permanent and increasingly destructive, posing a direct threat to humanity and the planet itself (see page one).

As with the ecological crisis, the only way out of this deadly impasse is the abolition of national economies and the states which defend them, and the creation of a global network of production and distribution, controlled by the producers themselves.

The beginning of a unified global humanity in harmony with nature

Communism will be global.

Capitalism has made it possible to create an extremely dense global economic fabric, with trade routes and complex links between factories and research centres, from country to country, in order to produce. The fragmentation of the current system into competing nations has therefore become totally obsolete: this division is an obstacle to the full realisation of the potential achieved by humanity. During the Covid 19 pandemic, the relentless race to be the first nation to find a vaccine, preventing laboratories from sharing their advances, considerably slowed down research. In the case of AIDS, scientists estimate that the war between French and American researchers, who lied to each other, spied on each other and competed with each other, cost the discovery of triple therapy more than a decade! This fragmentation of society is having the same devastating effects on research to combat the ecological crisis.

The future society, communism, will inevitably have to overcome this division; it will have to unite all humanity. Communism will therefore be the exact opposite of what Stalinism proclaimed: ‘socialism in one country’. This future society, a social and conscious organisation on a planetary scale, implies a giant leap forward. Human beings’ entire relationship with each other and with nature will be turned upside down. The separation between intellectual and manual labour will be abolished, and the opposition between town and country will no longer exist.

Communism will therefore be anything but a return to the past. It will draw on “the entire wealth of previous development” (Marx, 1844 MS), critically re-appropriating all the best achievements of past human societies, beginning with a new understanding of the more harmonious relationship between human beings and nature that prevailed in the long epoch of ‘primitive communism’. And in particular, it will be able to integrate, develop and at the same time radically transform all the scientific and technological advances made possible by capitalism.

The revolution for communism will be faced with gigantic tasks - not only reversing the ecological consequences of the capitalist mode of production, but also feeding, clothing and housing the whole world, and freeing all human beings from paralysing and dehumanising labour. But the ultimate goal of communism is not simply the negation of capitalism, it is a new synthesis, a new and higher relationship between humanity and nature, which becomes self-aware. This goal is not a distant ideal, but a guiding principle for the entire revolutionary process. Communism and nature will mean “consciously rational treatment of the earth as eternal communal property, and as an inalienable condition for the existence and reproduction of the chain of successive human generations” (Marx, Capital, Volume 3).

Rubric:

5) What is the social force that can bring about revolution?

- 147 reads

The only solution to the infernal spiral of ecological and military destruction is to overthrow capitalism and move towards communism. But the bourgeoisie will never accept the end of its system, the end of its privileges, the end of its existence as a dominant and exploiting class. It will try to maintain its obsolete system at all costs. Only a world revolution can put an end to this agony. For all those who are concerned about the state of the planet and the fate of humanity, the essential question is: what social force is capable of bringing about revolution?

What is the revolutionary class in capitalist society?

“The history of all societies up to the present day is the history of class struggles”. These are the opening words of the Manifesto of the Communist Party of 1848, written by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. In this fundamental document, which retains its value to this day, we see how the class struggle has unfolded in all historical societies, how it was in fact at the heart of the radical transformation of these societies. Ancient slavery was replaced by feudalism, feudalism by capitalism. Each time, a revolutionary process was led by a new class born from the womb of existing society:

- Faced with the slave-masters of decadent Rome, for centuries there were revolts by slaves and gladiators – most famously the Spartacus revolt of 73-71 BCE. But despite their courage, they were powerless to overturn slave society. It was the feudalists who represented the revolutionary class of the time, the class capable of replacing slavery, which had entered its epoch of decadence, with a new social organisation of production capable of overcoming the insoluble contradictions of the old society and thus installing a new form class exploitation, based on serfdom.

- Faced with the decadent feudal lords, there were many rebellions by the peasants against exploitation, such the ‘Jacqueries’ in France or the Peasants’ Revolt in England in 1381. But they too were powerless to change society. It was the bourgeoisie who represented the revolutionary class of the time, the class capable of overthrowing decadent feudalism and ushering in a new social organisation of production, this time based on the wage system.

In capitalism, this revolutionary role falls to the proletariat – the first exploited class capable of transforming society from top to bottom. In the past, the contradictions assailing societies in their period of decadence could not be overcome by abolishing exploitation but only by bringing in a new mode of production itself based on exploitation. But the contradictions that provoke the historic crisis of capitalism, the result of the very laws of this system – of production being based not on based not on human need but for the market and profit, on competition between enterprises and states - are rooted in the exploitation of the class which produces the essential of social wealth, the proletariat. Because, under capitalism, labour power has become a commodity which is sold to the owners of the means of production, the capitalists; because the producers are exploited, because competition on the market forces the capitalists (whatever their ‘good intentions’) to increase exploitation more and more, the abolition of the contradictions assailing capitalism necessarily entails the abolition of exploitation. This is why, under capitalism, the revolutionary class can no longer be a new exploiting class, as in the past, but has to be the main exploited class under this system, the proletariat.

Faced with the decadent bourgeoisie, there are a thousand reasons to revolt. All humanity suffers, all strata, all the exploited are tortured. But the only social force capable of overthrowing the bourgeoisie, its states and its forces of repression, and of proposing another perspective, is the working class. The proletariat is fundamentally different from the producing and exploited classes that preceded it. In slave and feudal societies, the instruments of labour were individual or, at best, communal. The basis of production was therefore isolated, fragmented, locally limited, individual labour. The major upheaval brought about by capital stems precisely from the replacement, as the predominant basis of production, of individual labour by collective labour. In place of isolated individual labour, the manufacture of goods has developed through the associated labour of thousands of human beings, carried out on the scale of the globe (for example, a modern automobile is made up of parts produced in countless factories and countries). In this way, capital has created, in place of the scattered exploited classes, isolated from each other, a class which is united by its collective labour (and this on a world scale) and which can only live and work thanks to this unity. In this way, capitalism has produced, with the modern proletariat, its own gravedigger. And as an exploited class, it has no interest in creating a new form of domination and exploitation. It can only free itself by freeing the whole of humanity from all forms of exploitation and oppression. It is in the struggle that workers forge the unity that is their strength. On a daily basis, capitalism divides them by pitting them against each other, between colleagues, between teams, between units, between factories, between companies, between sectors, between nations. But when they start to stand up for their working conditions, solidarity binds them together. And then “sometimes the workers triumph, but it's a fleeting triumph. The real result of their struggles is not so much immediate success as the growing unity of the workers” (Manifesto of the Communist Party, 1848). Karl Marx described the whole process as follows: “Large-scale industry brings together in one place a crowd of people unknown to each other. Competition divides their interests. But the maintenance of wages, this common interest they have against their master, unites them in a single thought of resistance - coalition. Thus the coalition always has a double aim, that of putting an end to competition between them, in order to be able to compete generally with the capitalist. If the first aim of resistance was only the maintenance of wages, as the capitalists in their turn unite in a thought of repression, the coalitions, at first isolated, form into groups, and in the face of capital always united, the maintenance of the association becomes more necessary for them than that of wages. (...) Economic conditions had first transformed the mass of the country into workers. The domination of capital has created for this mass a common situation, common interests. Thus this mass is already a class in relation to capital, but not yet for itself. In the struggle, of which we have only mentioned a few phases, this mass comes together and constitutes a class for itself. The interests it defends become class interests. But the struggle of class against class is a political struggle”. (Marx, Poverty of Philosophy)

This is what lies behind every strike: a potential process of unification, organisation and politicisation of the entire working class, the formation of a social power capable of standing up to capitalism. Because by fighting together for their living and working conditions, workers are attacking the very heart of capitalism: exploitation, profit, commodification and competition. That's why Lenin said that “behind every strike lies the hydra of revolution”.

Luxemburg and Lenin were witnesses to the first great revolutionary struggles of the working class in the 20th century – 1905 in Russia, and 1917-19 in Russia, Germany, and around the world. In those epic battles workers were faced with the growing incorporation of their own organisations (trade unions and parties) into the existing state apparatus. But in response they were able to create new organs of struggle– the soviets or workers’ councils, capable of unifying the class and laying the basis for a new form of political power that could confront and dismantle the bourgeois state and begin the process of “expropriating the expropriators”: the transition to a communist society. These movements were a real confirmation of the revolutionary nature of the working class.

Of course, soviets or workers’ councils can only appear at a very advanced level of the class struggle. They cannot exist permanently inside capitalist society. But the fact that they correspond to the needs of the class movement in this epoch – the need for unity across sectional and national boundaries, the need to raise the struggle to the political level – is shown by the fact in many of the struggles since 1968, workers have come together in mass assemblies and elected, revocable strike committees that are the embryonic form of the future councils. This was demonstrated most clearly by the Inter-Factory Strike Committees produced by the mass strike in Poland in 1980.

And what about the climate?

Rosa Luxemburg wrote that the workers' movement is not just a “bread and butter” question, but also “a great cultural movement”. From the 19th century onwards, workers incorporated into their struggle the fight against all the scourges of capitalism: war, inequality between men and women, between blacks and whites, the mistreatment of the sick... and pollution. The question of nature and the environment belongs entirely to the revolutionary struggle of the working class. In 1845, in his book The Condition of the Working Class in England, Engels was already denouncing the effects of polluted air, overcrowding and untreated sewage on the health of the workers; the Manifesto of 1848 already demanded that the separation between town and country had to be overcome; in his later years Marx avidly studied the harmful effects on the soil of capitalism’s “robbery agriculture”.

In other words, it is the revolutionary struggle of the working class against exploitation and for communism that contains, encompasses and carries behind it all the other causes, all the other revolts, including the struggle for the planet. What revolutionaries and all those concerned about the state of the world must defend is therefore the exact opposite of the current theory of ‘inter-sectionality’. This theory puts the workers' struggle, the fight against racism and the fight for the climate on the same level, and claims that all these struggles must ‘converge’, march side by side in the same impetus. In other words, it's a theory for the dilution of the proletarian struggle, of the disappearance of the workers in the midst of an amorphous mass of ‘citizens’. It's a devious tactic to divert the workers from their historic struggle to overthrow the capitalist system. It's a trap!

Does the working class still exist?

The big lie equating Stalinism with communism (see article on page 3) enabled the bourgeoisie to mount a deafening campaign in 1990, at the time of the collapse of the USSR, to proclaim everywhere the death of communism. It hammered home the message that any revolutionary dream could only turn into a nightmare. That capitalism had triumphed once and for all. Worse still, it even managed to make workers believe that the working class no longer existed, that it was a quaint old thing from another century. ‘Employees’, ‘collaborators’, ‘middle class’... the New Speak worthy of George Orwell's 1984 has finished hammering this new ‘reality’ into people's heads.

But facts are stubborn. Not only have workers not disappeared, they have never been so numerous on a global scale. Including in Europe. Because the proletariat is not just made up of blue-collared factory workers. All those who are forced to sell their labour power to make a living are workers. Manual workers or intellectuals, producers or service workers, in the private sector or the public sector, it doesn't matter; they form one and the same class, waging one and the same struggle.

The working class exists! And today it is rediscovering the path of struggle.

It is true that since 1990, the working class has waged very few struggles, stunned by the blow of the campaign on the so-called ‘death of communism’. It’s also true that the ruling class took advantage of the defeats suffered by the working class in the 80s, of its disorientation in the 90s, to break up many traditional centres of working class militancy (such as the coal mines in the UK, steel plants in France, car production in the US). All this combined to undermine the awareness in the working class that it was indeed a class with its own distinct interests. Losing confidence in its revolutionary project, in the future, it had also lost confidence in itself. It was resigned. But today, faced with the worsening of the economic crisis, inflation, the increasingly unbearable wave of impoverishment and precariousness, the proletariat has taken up the path of struggle once again. After years of stagnation in the struggle, the workers are beginning to raise their heads. It was the workers of Great Britain who first announced this comeback during the ‘Summer of Anger’ in 2022. Since then, strikes have multiplied around the world. The challenge for the period ahead is for workers to unite, to overcome the poison of corporatism, to take their struggles into their own hands and to organise themselves. But they will also have to integrate all the crises of capitalism into their struggle: the war crisis, the social crisis and the climate crisis! This is what was lacking in the wave of international struggle that began in May 1968 and spread from country to country until the 1980s: the proletariat at that time had not been able to sufficiently politicise its struggle.

That's why all those who are convinced of the need for revolution, whether in the face of the climate crisis, the economic crisis or war, have a primary responsibility to participate in this politicisation: by coming to debate in demonstrations, assemblies, political discussion circles and struggle groups formed by the most combative workers. Above all, they need to work towards the construction of the revolutionary political organisation, which has the specific role of defending the historical lessons of the class struggle, of maintaining and developing the communist programme. Today such organisations may be small and can’t yet have a direct impact on the course of the class struggle, but they must see themselves as an indispensable bridge towards the future world party of the communist revolution.

6) Further Reading

| Attachment | Size |

|---|---|

| 798.09 KB |

- 136 reads

Radical ecologism or communism: further reading

For a more developed critique of the various radical ecologist theories, see our recent articles:

- Critique of Saito's "Degrowth Communism" [7]

- Andreas Malm: 'Ecological' rhetoric in defence of the capitalist state [8]

We respond to Saito’s claim that Marx’s researches into questions around ecology and pre-capitalist communal forms led him to abandon historical materialism and to adopt what Saito calls “degrowth communism”. The article on Malm focuses on showing that, despite his radical, pseudo-marxist rhetoric, Malm insists on the need to work inside the framework of the existing capitalist state. In both cases, there is a systematic rejection of the proletarian revolution as the only solution to the ecological crisis.

Other articles by the ICC on the ecological crisis include:

- Capitalism is poisoning the earth [9] (International Review 63, 1990)

- The world on the eve of an environmental disaster, International Review, 135 [10]

- T [11]he world on the eve of an environmental disaster: who is responsible?, International Review 139 [11]

- No solution to the ecological catastrophe without the emancipation of labour from capitalist exploitation [12], ICConline, 2019, focusing on the method used by Engels to understand the relationship between humanity and its environment

- Bordiga and the Big City [13], International Review 166, 2020. A study of the work of the Italian left communist Amadeo Bordiga, who, already in the 1950s and 1960s, displayed an acute insight into capitalism’s destructive relationship with nature.

ALSO, SEE THE PDF OF THIS MANIFESTO: PRINT IT OUT AND CIRCULATE IT!