Submitted by International Review on

IR 42, 3rd Quarter 1985

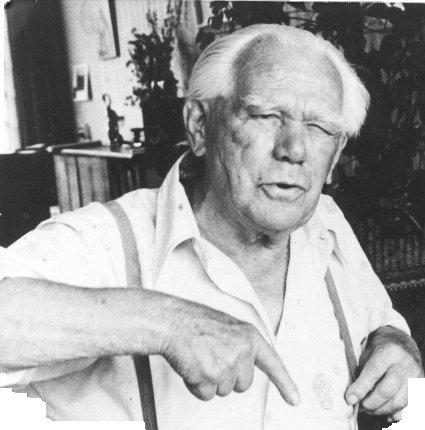

JAN APPEL: A REVOLUTIONARY HAS DIED

On the Fourth of May (1985), the last great figure of the Communist International, Jan Appel, died at the age of 95. The proletariat will never forget this life, a life of struggle for the liberation of humanity.

The

revolutionary wave of the beginning of this century ran aground. Thousands of revolutionary

marxists were killed in Russia and

Germany,

some even committing suicide. But, despite this long night of the counter-revolution,

Jan Appel remained true to marxism. He remained faithful to the working class,

convinced that the proletarian revolution would come.

Jan Appel was formed and tempered in the

revolutionary movement in Germany and

Holland at

the beginning of this century. He fought side by side with Rosa Luxemburg, Karl

Liebknecht, Lenin, Trotsky, Gorter, Pannekoek. He fought in the German

revolution in 1918—19. He was one of those who never betrayed the cause of the

proletariat. He was a worthy representative of this anonymous mass of the dead

generations of the proletariat. Their historic struggle always renounced the glorification

of personalities or the search for exalted titles. Just like Marx and Engels,

Jan Appel never had anything to do with the sensationalist capitalist press.

But he was also more than this anonymous mass of courageous revolutionary militants produced by the revolutionary wave of the workers’ movement at the beginning of our century. He left behind him traces which permit revolutionaries today to take up the torch. Jan Appel was able to recognise those who, just as anonymously, and reduced for the moment to a small minority, continued the communist combat. It was thus with pride that we welcomed Jan Appel to the founding Congress of the International Communist Current in 1976 in Paris

(An index of the initials used here is supplied at the end of this article.)

Born in 1890 in Mecklenburg in Germany, Jan Appel began at a very early age to work in the shipyards in Hamburg. From 1908 on he was an active member of the SPD. During the tormented war years, he took part in discussions on the new questions posed to the working class: its attitude in face of the imperialist war and of the Russian Revolution. This was what led him, at the end of 1917, beginning of 1918, to join up with the left radicals in Hamburg who had taken a clear position against the war, for the revolution. Thus he followed the July 1917 appeal of the Hamburg IKD calling on all revolutionary workers to work towards the constitution of an ‘International Social Democratic Party’ in opposition to the reformist-opportunist politics of the majority of the SPD. Pushed on by the workers’ struggles at the end of 1918, he also joined the Spartakusbund of Rosa Luxemburg and took up, after the formation of the KPD(S), a position of responsibility in the district group in Hamburg.

1918 was above all the year of the great strikes in Hamburg and in the whole of Germany after November, in which Appel was to he found in the front line. The workers of the shipyards had in fact long been vanguard fighters who from the beginning adopted a revolutionary attitude, and, pushed by the IKD and the KPD(S), took the lead in the struggle against the orientations of the reactionary SPD, the centrist USPD and the reformist unions. It was in their midst that the revolutionary factory delegates, and afterwards the AAU, saw the light of day. To quote Appel himself:

“In January 1918, the armaments and shipyard workers (under military control), came to revolt everywhere against the straitjacket of the war, against hunger, lack of clothing, against misery. And this through the general strike. At first, the working class, the proletarians in uniform, didn’t understand these workers ... but news of the situation, of this combat of the working class, penetrated the most remote corners. And since the balance of forces was sufficiently ripe, since nothing could be saved from the military economy and the so—called German Empire, thus, the working class and the soldiers applied what they had learnt from the pioneers of January 1918” (Hempel, pseudonym of Jan Appel, at the Third Congress of the Communist International, July 1921).

And on the November strikes in Hamburg, Appel recalled:

“When, in November 1918 the sailors revolted and the workers of the shipyards in Kiel downed tools, we learned at the Vulkan military shipyard from the workers what had happened. There followed a secret meeting at the shipyards; the factory was under military occupation, work ceased, but the workers remained in assembly in the enterprise. A delegation of 17 volunteers was sent to the union headquarters, to insist on the declaration of a general strike. We insisted on holding an assembly, but it turned out that the known leaders of the SPD and of the unions took up an attitude opposed to the movement. There were hours of harsh discussions. During this time, at the Blohm und Voss shipyard, where 17,000 workers were employed, a spontaneous revolt broke out. And so, all the workers poured out of the factories, at the Vulkan shipyard too (where Appel worked) and set off towards the union house. It was at this moment that the leaders disappeared. The revolution had begun.” (Appel, 1966, in a discussion with H M Bock).

It was above all the revolutionary factory delegates elected at that moment who organised the workers in factory councils, independent of the unions. Jan Appel was elected, on account of his active and preponderant part in the events, as the president of the revolutionary delegates. It was he who, along with Ernst Thalmann, revolutionary shop steward of the USPD, was designated by a mass assembly after the assassination of Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Liebknecht to organise the following night a march on the Barenfeld Barracks, in order to arm the workers. The lack of centralisation of the councils, especially with Berlin, the dispersion and above all the weakness of the KPD(S) which was just forming itself, did not allow the movement to develop, and two weeks later the movement broke down. This led to the period when attention was mainly oriented towards the reinforcement of the organisation.

For the workers in struggle, the unions were dead organs. At the beginning of 1919, the local unions in Hamburg, among other places, were dissolved, the dues and funds were divided amongst the unemployed. In August, the Conference of the northern district of the KPD(S), with Hamburg at the head, obliged its members to leave the unions. According to Appel:

“At that moment, we reached the conclusion that the unions were unusable for the revolutionary struggle, and that led, at an assembly of the revolutionary delegates to propaganda for the constitution of revolutionary factory organisations, as the basis for the councils. Departing from Hamburg, this propaganda for the formation of enterprise organisations spread, leading to the Allgemeine Arbeiter Unionen (AAU)” (ibid.).

On the 15 August, the revolutionary delegates met in Essen, with the approval of the Central Committee of the KPD(S) to found the AAU. In the paper of the KAZ different articles appeared at this time explaining the basis for the decision and why the unions no longer had a raison d’etre for the working class in decadence, and therefore the revolutionary period, of the capitalist system.

Jan Appel, as the president of the revolutionary delegates, and an active organiser, was thus also elected president of the KPD(S) of Hamburg. During the subsequent months, the tensions and conflicts between the central committee of Paul Levi, and the northern section of the KPD(S) in particular, multiplied, above all around the question of the unions, the AAU and the mass party. At the Second Congress of the KPD in October 1919 in Heidelberg, where the questions of the utilisation of parliamentarism and the unions were discussed and voted, Appel, as the president and delegate of the Hamburg district, took up a clear position against the opportunist theses which were opposed to the most revolutionary developments. The opposition, although in a majority, was excluded from the party: at the Congress itself, 25 participants were excluded straight away. The Hamburg group in its quasi-totality declared itself in agreement with the opposition, being followed by other sections. After making different attempts at opposition within the KPD(S), in February 1920 all the sections in agreement with the opposition were finally excluded. But it wasn’t until March that all efforts to redress the KPD(S) from within broke down. March 1920 was in fact the period of the Kapp Putsch, during which the central committee of the KPD(S) launched an appeal for a general strike, while propagating a line of ‘loyal opposition’ to the social democratic government and negotiating to avoid any armed revolutionary revolt. In the eyes of the opposition, this attitude was a clear and cutting sign of the abandonment of any revolutionary politics.

When in April 1920 the Berlin group left the KPD, the basis was given for the construction of the KAPD; 40,000 members, among them Jan Appel, had left the KPD.

In the insurrectional combats of the Ruhr in March 1920, Jan Appel was once more to be found in the foremost ranks, in the unionen, in the assemblies, in the struggles. On the basis of his active participation in the struggles since 1918 and of his organisational talents, the participants at the Founding Congress of the KAPD appointed Appel and Franz Jung to represent them at the Communist International in Moscow. They came to negotiate adhesion to the Third International and to discuss the treacherous attitude of the Central Committee of the KPD during the insurrection in the Ruhr. In order to get to Moscow, they had to divert the course of a ship. On arrival they held discussions with Zinoviev, president of the Communist International, and with Lenin. On the basis of Lenin’s text Left-Wing Communism — an Infantile Disorder, they discussed at great length, refuting among other things the false accusation of syndicalism (in other words the rejection of the role of the party) and of nationalism. Thus Appel, in his article ‘Information on Moscow’ and ‘Where is Ruhle heading?’ in the KAZ, defended the position that Laufenberg and Wolfheim ought to be excluded “since we can have more confidence in the Russian communists than in the German nationalists who have left the terrain of the class struggle”. Appel declared also that he had “judged that Ruhle also no longer found himself on the terrain of the programme of the party; if this vision had proven itself to be wrong, the exclusion of Ruhle would not have been posed. But the delegates had the right and the duty in Moscow to defend the programme of the party.”

He made many more trips to Moscow to get the KAPD admitted as a sympathising organisation to the IIIrd International, and thereby participated at the Third Congress in 1921.

In the meantime, Appel had travelled around Germany under the false name of Jan Arndt, and was active wherever the KAPD and the AAUD sent him. Thus, he became responsible for the weekly Der Klassenkampf of the AAU in the Ruhr, where he remained until November 1923.

At the Third Congress of the Communist International, in 1921, Appel again, along with Meyer, Schwab and Reichenbach, were the delegates to conduct the final negotiations in the name of the KAPD, against the growing opportunism of the CI. They attempted in vain to form a left opposition with the delegations of Bulgaria, Hungary, Luxemburg, Mexico, Spain, Britain, Belgium and the USA. Firstly, ignoring the sarcasms of the Bolshevik delegation or the KPD, Jan Appel, under the pseudonym of Hempel, underlined at the end of the Third Congress some fundamental questions for the world revolution today. Let us recall his words:

“The Russian comrades lack an understanding of what is happening in Western Europe. The Russian comrades have experienced a long Czarist domination, they are hard and solid, whereas where we come from the proletariat is penetrated by parliamentarism and is completely infested by it. In Europe we have to proceed differently. The path to opportunism has to be barred ... Opportunism among us is the utilisation of bourgeois institutions in the economic domain ... The Russian comrades are not supermen either, and they need a counterweight, and this counterweight must be a IIIrd International ridding itself of any tactic of compromise, parliamentarism and the old unions.”

Appel was arrested in November 1923 on the charge of inciting mutiny on the ship with which the delegation had arrived in Moscow in 1920. In prison he prepared a study of the workers’ movement and in particular of the period of transition towards communism, in the light of the lessons of events in Russia.

He was set free at the end of 1925, but Germany had become dangerous for him, and he obtained work at a shipyard in Holland. He immediately took contact with Canne-Meyer, whom he had not known personally, in order to be able to integrate himself into the situation in Holland. Departing from this contact, ex—members of the KPN and/or the KAPN regrouped slowly, and in 1927 formed the GIC which published a review, Press Material of the International Communists (PIC), as well as an edition in German. It closely followed the evolution of the KAPD in Germany and oriented itself more towards the Theses of the Berlin KAPD, in opposition to the group around Gorter. Over four years, the GIC studied and discussed the study which Appel had made in prison, and the book Foundations of Communist Production and Distribution was published in 1930 by the Berlin AAU, a book which has been discussed and criticised by revolutionaries throughout the world to this very day.

Appel made many other important contributions during the difficult years of the counter-revolution, up until World War II, against the positions of the degenerating Communist Parties, rapidly becoming bourgeois. The GIC worked in contact with other small revolutionary organisations in different countries (like the Ligue des Communistes Internationalistes in Belgium, the group around Bilan, Union Communiste in France, the group around Paul Mattick in the USA etc.), and was one of the most important currents of this period in keeping internationalism alive. From 1933 on Appel kept in the background, since the Dutch state, on good terms with Hitlerite Germany, would have expelled him. Until 1948, Appel remained in clandestinity under the name of Jan Vos.

During and after the second world war however, Appel and other members of the GIC regrouped with the Spartacusbond coming out of the ‘Marx— Lenin—Luxemburg Front’, the only internationalist organisation in Holland until 1942. The members of the GIC, who were expecting, like all the other revolutionary organisations at that time, important class movements after the war, considered it important to regroup, even if there still existed divergences between them, in order to prepare a more important, stronger revolutionary organisation, with the aim of playing a more preponderant role in the movements. But these movements did not develop, and numerous discussions cropped up in the group on the role and the tasks of the political organisation. Appel remained within the Spartacusbond and defended positions against the councilist ideas which were being reinforced within the group. Almost all the GIC members left the group in 1947, only to quickly disappear into the void. Witness a letter by Pannekoek, himself having become a councilist, in September 1947:

“And now that the strong mass movement hasn’t turned up, nor the influx of young workers (we had counted on this for the period after the war, and it was certainly the fundamental motive of the GIC in regrouping with Spartacusbond in the last year of the war), it follows logically that the GIC returned to its old role, not preventing the Spartacusbond from returning to its old role as RSP. According to my information, the question of which form of propaganda to choose is presently being discussed in the GIC ... it’s a pity that Jan Appel has stayed with the people of Spartacusbond. Already in the past, I have noted how his spirit and his conceptions are determined by his experiences in the great German movement which was the culminating point of his life. It’s there that he formed his understanding of the organisational techniques of the councils. But he was too much a man of action to be content with simple propaganda. But the wish to be a man of action in a period in which the mass movement doesn’t yet exist, easily leads to the formulation of impure and mystified forms of action. Perhaps it’s a good thing after all that Spartacus has held on to one strong element.”

By accident, Appel was re-discovered by the Dutch police in 1948. After encountering many difficulties, he was allowed to stay in Holland, but was forbidden any political activity. Appel thus formally left Spartacusbond and organised political life.

After 1948, however, Appel remained in contact with his old comrades, both in Holland and elsewhere, among others with Internationalisme, predecessor of the ICC, at the end of the forties and during the fifties. That’s why Jan Appel was once again present at the end of the sixties at the founding of Revolution Internationale, the future section in France of the ICC, and a product of the massive struggles of the proletariat in 1968. Since then with numerous visits from comrades and sympathisers of the ICC, Jan Appel contributed to the formation of a new generation of revolutionaries, participating at the formal constitution of the ICC in 1976, one last time, thereby passing on the torch and the lessons of one generation of revolutionaries to another.

Until the very end, Jan Appel was convinced that “only the class struggle is important”. We continue his struggle.

For the ICC,

A. Bal

BIBLIOGRAPHY

To be found in issues of the International Review:

· ‘The Councilist Danger’, IR 40;

· ‘The Communistenbond Spartacus and the Councilist Current’, IR 38 & 39;

· ‘The Bankruptcy of Councilism’, ‘Organisational Conceptions in the German-Dutch Left’, IR 37;

· ‘Critique of Pannekoek’s ‘Lenin as Philosopher’, IRs 25, 27, 28, 30;

· ‘The Dutch Left’, IRs 16,17,27;

· ‘Breaking with Spartacusbond’, IR 9;

· ‘The Epigones of Councilism at Work: Spartacusbond, Daad en Gedachte’, IR 2.

INDEX OF THE INITIALS USED:

GIC: International Communist Group

KAZ: Communist Workers’ Journal

USPD: Independent Social Democratic Party of Germany

RSP: Revolutionary Socialist Party, a split from the KPN (1925-35) which was turned into the Marx-Lenin-Luxemburg front(MLL front) in 1940.

PIC: Press Material of the International Communists

KPN: Communist Party of the Netherlands

KAPN: Communist Workers Party of the Netherlands

KAPD: Communist Workers Party of Germany

KPU(S): Communist Party of Germany/Spartacus.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us Digg

Digg Newskicks

Newskicks Ping This!

Ping This! Favorite on Technorati

Favorite on Technorati Blinklist

Blinklist Furl

Furl Mister Wong

Mister Wong Mixx

Mixx Newsvine

Newsvine StumbleUpon

StumbleUpon Viadeo

Viadeo Icerocket

Icerocket Yahoo

Yahoo identi.ca

identi.ca Google+

Google+ Reddit

Reddit SlashDot

SlashDot Twitter

Twitter Box

Box Diigo

Diigo Facebook

Facebook Google

Google LinkedIn

LinkedIn MySpace

MySpace