Submitted by ICConline on

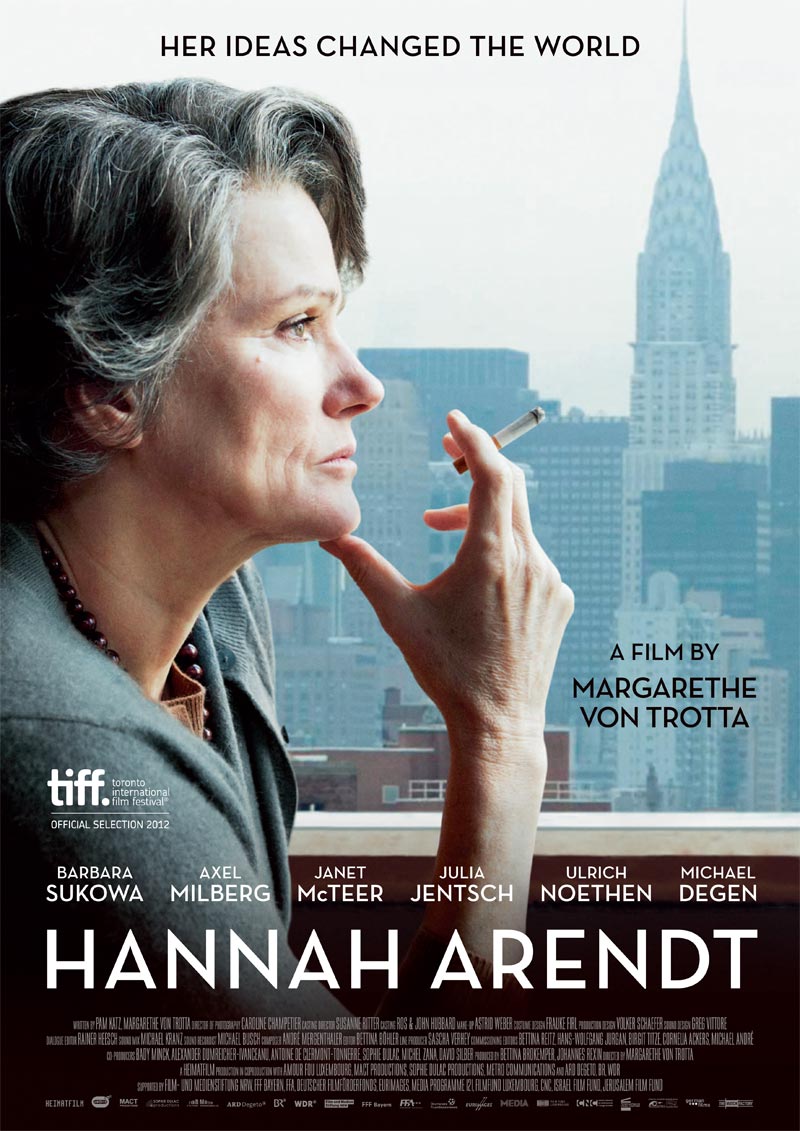

Germany's tormented 20th century history is rich in dramatic and terrible themes, as a number of successful films that have hit the screens over the last few years demonstrate: The pianist, for example1 (on the Warsaw ghetto), or Goodbye Lenin and The lives of others (on East Germany and the fall of the Berlin Wall). The producer Margerete von Trotta has already drawn inspiration several times from these deep waters, and has not hesitated to deal with some difficult subjects: witness Two German sisters (Die Bleieme Zeit, 1981), a dramatised version of the life and death (in Stammheim prison, in circumstances which were never completely clarified) of the Red Army Fraction terrorist Gudrun Ensslin; a biopic of Rosa Luxemburg (1986); Rosenstrasse (2003), on a demonstration against the Gestapo in 1943 of German women protesting at the arrests of their Jewish husbands. In her new film, Hannah Arendt (2012 in Germany, 2013 in the USA and Britain), von Trotta returns to the subject of the war, the Shoah, and nazism, through an episode in the life of the eponymous German philosopher, remarkably played by Barbara Sukowa, who also played the role of the young Rosa Luxemburg twenty years ago.

Germany's tormented 20th century history is rich in dramatic and terrible themes, as a number of successful films that have hit the screens over the last few years demonstrate: The pianist, for example1 (on the Warsaw ghetto), or Goodbye Lenin and The lives of others (on East Germany and the fall of the Berlin Wall). The producer Margerete von Trotta has already drawn inspiration several times from these deep waters, and has not hesitated to deal with some difficult subjects: witness Two German sisters (Die Bleieme Zeit, 1981), a dramatised version of the life and death (in Stammheim prison, in circumstances which were never completely clarified) of the Red Army Fraction terrorist Gudrun Ensslin; a biopic of Rosa Luxemburg (1986); Rosenstrasse (2003), on a demonstration against the Gestapo in 1943 of German women protesting at the arrests of their Jewish husbands. In her new film, Hannah Arendt (2012 in Germany, 2013 in the USA and Britain), von Trotta returns to the subject of the war, the Shoah, and nazism, through an episode in the life of the eponymous German philosopher, remarkably played by Barbara Sukowa, who also played the role of the young Rosa Luxemburg twenty years ago.

Hannah Arendt was born into a Jewish family in 1906. As a young student, she attended the classes of the philosopher Martin Heidegger, with whom she had a brief but intense love affair. The fact that she never disowned either the relationship or Heidegger himself, despite the latter's joining the NSDAP2 in 1933 was to be harshly criticised later; her ties with Heidegger and his philosophy were undoubtedly complex, and would almost merit a book in themselves, and the flashbacks to her encounters with Heidegger are perhaps the least successful in the film, the only scenes where von Trotta seems less sure of her film's theme: the "banality of evil".

Arendt fled Germany in 1933 with Hitler's coming to power, and moved to Paris where she worked in the Zionist movement despite her critical attitude towards it. It was in Paris that she married, in 1940, her second husband Heinrich Blücher. Following Germany's invasion of France she was interned by the French state in the camp of Gurs, but managed to flee and – not without difficulty – reached the United States in 1941. Penniless on her arrival, she managed to earn her living and finally succeeded in winning an appointment to the prestigious Princeton University (she was the first woman to be accepted as a professor by Princeton). By 1960, when the film opens, Arendt was a respected intellectual and had already published two of her most famous works: The origins of totalitarianism (1951) and The human condition (1958). Although she was certainly not a marxist, she was interested by Marx's work, and by that of Rosa Luxemburg.3 Her husband Heinrich had been a Spartakist, then a member of the opposition to the Stalinisation of the KPD during the 1920s, joining Brandler and Thalheimer in the KPD-Opposition (aka KPO) when they were excluded from the party.4 The film makes a passing reference to Heinrich's party membership: we learn from one of the couple's American friends that "Heinrich was with Rosa Luxemburg to the end". And Arendt's philosophical work, especially her analysis of the mechanisms of totalitarianism remains relevant to this day. Her rigorous thought and her integrity allowed Arendt to pierce the clichés and commonplaces of her epoch's ruling ideology: she disturbed by her honesty.

The film's first moments evoke Adolf Eichmann's kidnapping in Argentina by the Mossad. Under the Nazi regime, Eichmann had occupied several important positions, organising first the Jews' expulsion from Austria, then the logistics of the "Final Solution", in particular the transport of European Jews to the death camps of Auschwitz, Treblinka, and others. The intention of David Ben-Gurion, Prime Minister of Israel and so responsible for the Mossad operation, was clearly to mount a show trial which would cement the foundations of the young state, and where the Jews themselves would judge one of the authors of their genocide.

On learning of the coming Eichmann trial, Arendt volunteered to report on the trial for the literary review The New Yorker. Her detailed and meticulous report on the trial appeared first as a series of articles, then in book form under the title Eichmann in Jerusalem: a report on the banality of evil. The publication caused a huge scandal in Israel and even more in the United States: Arendt was subjected to a violently hostile media campaign – "self-hating Jew" and "Rosa Luxemburg of nothingness" were only two of the more sober epithets aimed at her. She was asked to resign her university position, but refused. This period, the evolution of Arendt's thinking and her reaction to the media campaign, provide the material for the film. And when you think about it, it's a tall order to make a film of the contradictory and sometimes painful evolution of a philosopher's thinking, without trivialising it – and von Trotta and Sukowa rise to the challenge with brio.

Why then did Arendt's report create such a scandal?5 Up to a point, such a reaction was understandable and even inevitable: although Arendt wields criticism like scalpel, with all the skill of a surgeon, but for many the war and the abominable suffering of the Shoah were still too close, the trauma too recent, to be able to distance themselves from events. But the loudest voices were also the most interested: interested above all in drawing a veil of silence over the uncomfortable truths that Arendt's critique revealed.

Arendt cut to the quick when she took apart Ben-Gurion's attempt to make a show of Eichmann's trial, to justify Israel's existence by the Jews' suffering during the Shoah. For this to work, Eichmann had to be a monster, a worthy representative of the Nazis' monstrous crimes. Arendt herself expected to see a monster in the dock, but the more she observed him, the less she was convinced, not of his guilt but of his monstrosity. In the trial scenes, von Trotta places Arendt not in the tribunal itself, but in a press room where the journalists watch the trial over CCTV. This device allows von Trotta to show us, not an actor playing Eichmann, but Eichmann himself; like Arendt, we can see this mediocre man (Arendt uses the term "banality" in its sense of "mediocrity"), who has nothing in common with the murderous madness of a Hitler, or the no less mad coldheartedness of a Goebbels (as they have been brilliantly interpreted by Bruno Ganz and Ulriche Mathes in Downfall). On the contrary, we are confronted with a petty bureaucrat whose intellectual horizon barely extends beyond the walls of his office and its good order, and whose perspectives are limited to his hopes for promotion and bureaucratic rivalries. Eichmann is not a monster, is Arendt's conclusion: "it would have been very comforting indeed to believe that Eichmann was a monster (…) The trouble with Eichmann was precisely that so many were like him, and that the many were neither perverted nor sadistic, that they were, and still are, terribly and terrifyingly normal" (p274).6 In short, Eichmann's crime was not to have been responsible for the Jews' extermination in the same way as Hitler, but to have abdicated his capacity for thinking, and to have acted legally and with a quiet conscience as a mere cog in a the totalitarian machine of a criminal state. The undoubted "good sense" of "prominent personalities" served as his "moral guide". The Wannsee conference (which set in place the operational mechanisms of the "Final Solution") was thus "a very important occasion for Eichmann, who had never before mingled socially with so many 'high personages' (…) Now he could see with his own eyes and hear with his own ears that not only Hitler, not only Heydrich or the 'sphinx' Müller, not just the SS or the Party, but the elite of the good old Civil Service were vying and fighting with each other for the honor of taking the lead in these 'bloody' matters" (p111-2).

Arendt explicitly rejects the idea that "all Germans are potentially guilty", or "guilty by association": Eichmann deserved to be executed for what he had done himself (though his execution would hardly bring the millions of victims back to life). That said, her analysis is a courageous slap in the face for the anti-fascist ideology which has become official state ideology, notably in Israel. In our view, the "banality" that Arendt describes is that of a world – the capitalist world – where human beings, reified and alienated, are reduced to the status of objects, commodities, cogs in the machine of capital. This machine is not a characteristic of the Nazi state alone. Arendt reminds us that the policy of "Judenrein" (making a territory "Jewless") had already been explored by the Polish state in 1937, before the war, and that the thoroughly democratic French government, in the person of its foreign minister Georges Bonnet, had envisaged the expulsion to Madagascar of 200,000 "non-French" Jews (Bonnet had even consulted his German opposite number Ribbentrop for advice on the subject). Arendt also points out that the Nuremberg tribunal is nothing less than a "victors' tribunal", where the judges represent countries which were also responsible for war crimes: the Russians guilty of the deaths in the gulags, the Americans guilty of the nuclear bombardment of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

Nor is Arendt tender with the state of Israel. Unlike other reporters, she highlights in her book the irony of Eichmann's trial for race-based crimes by an Israeli state which itself incorporates racial distinctions into its own laws: "rabbinical law rules the personal status of Jewish citizens, with the result that no Jew can marry a non-Jew; marriages concluded abroad are recognized, but children of mixed marriages are legally bastards (…) and if one happens to have a non-Jewish mother he can neither be married nor buried". It is indeed a bitter irony that those who escaped from the Nazi policy of "racial purity" should have tried to create their own "racial purity" in the Promised Land. Arendt detested nationalism in general and Israeli nationalism in particular. Already in the 1930s, she had opposed Zionist policy and its refusal to look for a mode of life in common with the Palestinians. And she did not hesitate to expose the hypocrisy of the Ben-Gurion government, which publicised the ties between the Nazis and certain Arab states, but remained silent about the fact that West Germany continued to shelter a remarkable number of high-ranking Nazis in positions of responsibility.

Another object of scandal was the question of the "Judenrat" – the Jewish councils created by the Nazis precisely with the aim of facilitating the "Final Solution". It occupies only a few pages of the book, but it cuts to the quick. Here is what Arendt has to say about it: "Wherever Jews lives, there were recognized Jewish leaders, and this leadership, almost without exception, cooperated in one way or another, for one reason or another, with the Nazis. The whole truth was that if the Jewish people had really been unorganized and leaderless, there would have been chaos and plenty of misery but the total number of victims would hardly have been between four and a half and six million people (…) I have dwelt on this chapter of the story, which the Jerusalem trial failed to put before the eyes of the world in its true dimensions, because it offers the most striking insight into the totality of the moral collapse the Nazis caused in respectable European society" (p123). She even revealed an element of class distinction between the Jewish leaders and the anonymous mass: in the midst of the general disaster, those who escaped were either sufficiently rich to buy their escape, or sufficiently visible in the "international community" to be kept alive in Theresienstadt, a kind of privileged ghetto. The relationships between the Jewish population and the Nazi regime, and with other European populations, were much more complicated than the war victors' official manichean ideology was prepared to admit.

Nazism and the Shoah occupy a central place in modern European history, even more today than in the 1960s. Despite the best efforts of the authors of The black book of communism, for example, Nazism remains today the "ultimate evil". In France, the Shoah is an important part of the school history programme, along with the French Resistance, to the exclusion of almost any other consideration of the Second World War. And yet on the level of simple arithmetic, Stalinism was far worse, with the 20 million dead in Stalin's gulag and at least 20 million dead in Mao's "Great leap forward". Obviously, this owes a good deal to opportunist calculation: the descendants of Mao and Stalin are still in power in China and Russia, they are still people with whom one can and must "do business". Arendt does not deal directly with this question, but in a discussion of the charges against Eichmann, she insists on the fact that the Nazis' crime was not a crime against the Jews, but a crime against all humanity in the person of the Jewish people, precisely because it denied to the Jews their membership of the human species, and transformed these human beings into an inhuman evil to be eradicated. This racist, xenophobic, obscurantist aspect of the Nazi regime was clearly proclaimed, which indeed is why a part of the European ruling class, and of the peasant and artisan classes ruined by the economic crisis, could get along with it so comfortably. Stalinism on the contrary always claimed to be progressive: it could still sing that "the Internationale shall be the human race", and indeed this is why right up to the destruction of the Berlin Wall, and even afterwards, ordinary people could continue to defend the Stalinist regimes in the name of a better future to come.7

Arendt's major point is that the "unthinkable" barbarity of the Shoah, the mediocrity of the Nazi bureaucrats, is the product of the destruction of an "ability to think". Eichmann "does not think", he executes the orders of the machine, and does his job diligently and conscientiously, without any qualms, and without making the connection with the horror of the camps – of which he was nonetheless aware. In this sense, von Trotta's film should be seen as an elegy to critical thought.

Hannah Arendt was not a marxist, nor a revolutionary. But by posing questions which undermine official anti-fascist ideology, she is the enemy of commonplace conformism and the abandonment of critical thought. Her analysis has the merit of opening a reflexion on the human conscience (rather in the same way as the work of the American psychologist Stanley Milgram on the mechanisms of the "submission to authority" amongst torturers, dramatised in Henri Verneuil's film I comme Icare).

The publicity given to Arendt's work by the democratic bourgeoisie and its intelligentsia – for whom she has become something of an icon – is not innocuous. The recuperation of her analysis of totalitarianism clearly aims at establishing a continuity between Bolshevism and the Russian revolution of 1917, and the totalitarian machine of the Stalinist state: Stalin was only Lenin's executor, the moral being that proletarian revolution can only lead to totalitarianism and new crimes against humanity. This is what some established bourgeois ideologues like Raymond Aron have not hesitated to exploit Arendt's analysis of the Stalinist state's totalitarianism to feed their campaigns for the Cold War and the "collapse of communism" following the break-up of the USSR.

Hannah Arendt was a philosopher, and as Marx said "The philosophers have so far only interpreted the world. The point however, is to change it". Marxism is not a "totalitarian" doctrine but the theoretical weapon of the exploited class for the revolutionary transformation of the world. And this is why only marxism is truly able to integrate the contributions of art and science, and of past philosophers like Epicurus, Aristotle, Spinoza, Hegel... as well as those of our own time like Hannah Arendt, with her profound and critical view of the contemporary world, and her elegy to thought.

Jens

1See our critique of the film in n°113 of the International Review (https://en.internationalism.org/ir/113_pianist.html)

2The Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei (Nazi party)

3In 1966 Arendt reviewed JP Nettl's biography of Luxemburg in the New York Review of Books. In this article, she lashed both the Weimar and the contemporary Bonn governments with the scourge of her critique, declaring that the murders of Luxemburg and Liebknecht were carried out "under the eyes and probably with the connivance of the Socialist regime then in power (…) That the government at the time was practically in the hands of the Freikorps because it enjoyed 'the full support of Noske,' the Socialists’ expert on national defense, then in charge of military affairs, was confirmed only recently by Captain Pabst, the last surviving participant in the assassination. The Bonn government - in this as in other respects only too eager to revive the more sinister traits of the Weimar Republic - let it be known (through the Bulletin des Presse-und Informationsamtes der Bundesregierung) that the murder of Liebknecht and Luxemburg was entirely legal, 'an execution in accordance with martial law.' This was more than even the Weimar Republic had ever pretended...".

4The KPO was one of the oppositions to Stalinism which never fully broke with it because, like Trotsky, they were unable to accept the idea of a counter-revolution in Russia.

5For French speakers, there is an interesting documentary made up of radio interviews of the participants in the controversy podcast by France Culture: Hannah Arendt et le procès d'Eichmann

6The quotes are taken from the the Penguin edition published in 2006 with an introduction by Amos Elon.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us Digg

Digg Newskicks

Newskicks Ping This!

Ping This! Favorite on Technorati

Favorite on Technorati Blinklist

Blinklist Furl

Furl Mister Wong

Mister Wong Mixx

Mixx Newsvine

Newsvine StumbleUpon

StumbleUpon Viadeo

Viadeo Icerocket

Icerocket Yahoo

Yahoo identi.ca

identi.ca Google+

Google+ Reddit

Reddit SlashDot

SlashDot Twitter

Twitter Box

Box Diigo

Diigo Facebook

Facebook Google

Google LinkedIn

LinkedIn MySpace

MySpace