Submitted by International Review on

Introduction

The 100th anniversary of the foundation of the Communist International reminds us that the October revolution in Russia had placed the world proletarian revolution on the immediate agenda. The German revolution in particular was already underway and was crucial both to the survival of soviet power in Russia and to the extension of the revolution to the main centres of capitalism. At this moment, all the different groups and tendencies which had remained loyal to revolutionary marxism were convinced that the formation and action of the class party were indispensable to the victory of the revolution. But with hindsight we can say that the late formation of the CI –almost two years after the seizure of power in Russia, and several months after the outbreak of the revolution in Germany- as well as its ambiguities and errors on vital programmatic and organisational questions, was also an element in the defeat of the international revolutionary upsurge.

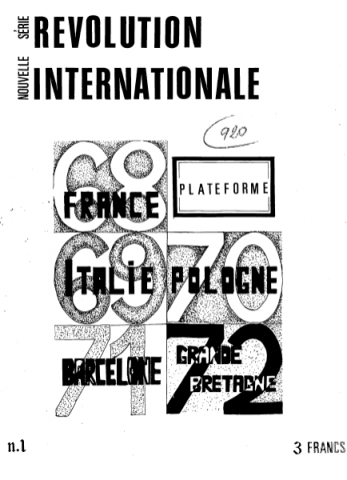

We need to bear this in mind when we look back at another anniversary: May 68 in France and the ensuing wave of class movements. In the two previous articles in this series, we have looked at the historic significance of these movements, expressions of the reawakening of the class struggle after decades of counter-revolution - the counter-revolution ushered in by the dashing of the revolutionary hopes of 1917-23. We have tried to understand both the origins of the events of May 68 and the course of the class struggle over the next five decades, focusing in particular on the difficulties facing the class in re-appropriating the perspective of the communist revolution.

In this article we want to look specifically at the evolution of the proletarian political milieu since 1968, and to understand why, despite considerable advances at the theoretical and programmatic level since the first revolutionary wave, and despite the fact that the most advanced proletarian groups have understood that it is necessary to take the essential steps towards the formation of a new world party in advance of decisive confrontations with the capitalist system, this horizon still seems to be very far away and sometimes seems to have disappeared from sight altogether.

1968-80: The development of a new revolutionary milieu meets the problems of sectarianism and opportunism

The global revival of the class struggle at the end of the 1960s brought with it a global revival of the proletarian political movement, a blossoming of new groups seeking to re-learn what had been obliterated by the Stalinist counter-revolution, as well as a certain reanimation of the rare organisations which had survived this dark period.

We can get an idea of the components of this milieu if we look at the very diverse list of groups contacted by the comrades of Internationalism in the US with the aim of setting up an International Correspondence Network[1]:

- USA: Internationalism and Philadelphia Solidarity

- Britain: Workers Voice, Solidarity

- France: Révolution Internationale, Groupe de Liaison Pour l’Action des Travailleurs, Le Mouvement Communiste

- Spain: Fomento Obrero Revolucionario

- Italy Partito Comunista Internazionalista (Battaglia Comunista)

- Germany Gruppe Soziale Revolution; Arbeiterpolitik; Revolutionärer Kampf

- Denmark: Proletarisk Socialistisk Arbejdsgruppe, Koministisk Program

- Sweden: Komunismen

- Netherlands: Spartacus; Daad en Gedachte

- Belgium: Lutte de Classe, groupe “Bilan”

- Venzuela; Internacionalismo

In their introduction Internationalism added that a number of other groups had contacted them asking to take part: World Revolution, which had meanwhile split from the Solidarity group in the UK; Pour le Pouvoir Internationale des Conseils Ouvrières and Les Amis de 4 Millions de Jeunes Travailleurs (France); Internationell Arbetarkamp, (Sweden), and Rivoluzione Comunista and Iniziativa Comunista (Italy).

Not all of these currents were a direct product of the open struggles of the late 60s and early 70s: many of them had preceded them, as in the case of Battaglia Comunista in Italy and the Internacialismo group in Venezuela. Some other groups which had developed in advance of the struggles reached their pinnacle in 68 or thereabouts and afterwards declined rapidly – the most obvious example being the Situationists. Nevertheless the emergence of this new milieu of elements searching for communist positions was the expression of a deep process of “underground” growth, of a mounting disaffection with capitalist society which affected both the proletariat (and this also took the form of open struggles like the strike movements in Spain and France prior to 68) and wide layers of a petty bourgeoisie which was itself already in the process of being proletarianised. Indeed the rebellion of the latter strata in particular had already taken on an open form prior to 68 – notably the revolt in the universities and the closely linked protests against war and racism which reached the most spectacular levels in the USA and Germany, and of course in France where the student revolt played an evident role in the outbreak of the explicitly working class movement in May 68. The massive re-emergence of the working class after 68, however, gave a clear answer to those, like Marcuse, who had begun theorising about the integration of the working class into capitalist society and its replacement as a revolutionary vanguard by other layers such as the students. It reaffirmed that the keys to the future of humanity lay in the hands of the exploited class just as it had in 1919, and convinced many young rebels and seekers, whatever their sociological background, that their own political future lay in the workers’ struggle and in the organised political movement of the working class.

The profound connection between the resurgence of the class struggle and this newly politicised layer was a confirmation of the materialist analysis developed in the 30s by the Italian Fraction of the Communist Left. The class party does not exist outside the life of the class. It is certainly a vital, active factor in the development of class consciousness, but it is also a product of that development, and it cannot exist in periods when the class has experienced a world-historic defeat as it had in the 20s and 30s. The comrades of the Italian left had experienced this truth in their own flesh and blood since they had lived through a period which had seen the degeneration of the Communist parties and their recuperation by the bourgeoisie, and the shrinking of genuine communist forces to small, beleaguered groups such as their own. They drew the conclusion that the party could only re-appear when the class as a whole had recovered from its defeat on an international scale and was once again posing the question of revolution: the principal task of the fraction was thus to defend the principles of communism, draw the lessons of past defeats, and to act as a bridge to the new party that would be formed when the course of the class struggle had profoundly altered. And when a number of comrades of the Italian left forgot this essential lesson and rushed back to Italy to form a new party in 1943 when, despite certain important expressions of proletarian revolt against the war, above all in Italy, the counter-revolution still reigned supreme, the comrades of the French communist left took up the torch abandoned by an Italian Fraction which precipitously dissolved itself into the Italian party.

But since, at the end of 60s and the early 70s, the class was finally throwing off the shackles of the counter-revolution, since new proletarian groups were appearing around the world, and since there was a dynamic towards debate, confrontation, and regroupment among these new currents, the perspective of the formation of the party – not in the immediate, to be sure – was once again being posed on a serious basis.

The dynamic towards the unification of proletarian forces took various forms, from the initial travels of Mark Chirik and others from the Internacialismo group in Venezuela to revive discussion with the groups of the Italian left, the conferences organised by the French group Information et Correspondence Ouvrières, or the international correspondence network initiated by Internationalism. The latter was concretised by the Liverpool and London meetings of different groups in the UK (Workers Voice, World Revolution, Revolutionary Perspectives, which had also split from Solidarity and was the precursor of today’s Communist Workers Organisation), along with RI and the GLAT from France.

This process of confrontation and debate was not always smooth by any means: the existence of two groups of the communist left in Britain today – a situation which many searching for class politics find extremely confusing - can be traced to the immature and failed process of regroupment following the conferences in the UK. Some of the divisions that took place at the time had little justification in that they were provoked by secondary differences – for example, the group that formed Pour une Intervention Communiste in France split from RI over exactly when to produce a leaflet about the military coup in Chile. Neverthleless, a real process of decantation and regroupment was taking place. The comrades of RI in France intervened energetically in the ICO conferences to insist on the necessity for a political organisation based on a clear platform in contrast to the workerist, councilist and “anti-Leninist” notions that were extremely influential at the time, and this activity accelerated their unification with groups in Marseille and Clermont Ferrand. The RI group was also extremely active at the international level and its growing convergence with WR, Internationalism, Internacialismo and new groups in Italy and Spain led to the formation of the ICC in 1975, showing the possibility of organising on a centralised international scale. The ICC saw itself, like the GCF in 40s, as one expression of a wider movement and didn’t see its formation as the end-point of the more general process of regroupment. The name “Current” expresses this approach: we were not a fraction of an old organisation, though carrying on much of the work of the old fractions, and were part of a broader stream heading towards the party of the future.

The prospects for the ICC seemed very optimistic: there was a successful unification of three groups in Belgium which drew lessons from the recent failure in the UK, and some ICC sections (especially France and UK) grew considerably in numbers. WR for example quadrupled in numbers from its original nucleus and RI at one point had sufficient members to set up separate local sections in the north and south of Paris. Of course we are still talking about very small numbers but nevertheless this was a significant expression of a real development in class consciousness. Meanwhile the Bordigist International Communist Party established sections in a number of new countries and quickly became the largest organisation of the communist left.

And of particular importance in this process was the development of the international conferences of the communist left, initially called by Battaglia and supported enthusiastically by the ICC even though we were critical of the original basis for the appeal for the conferences (to discuss the phenomenon of “Eurocommunism”, what Battaglia called the “social democratisation” of the Communist parties).

For three years or so, the conferences offered a pole of reference, an organised framework for debate which drew towards it a number of groups from diverse backgrounds[2]. The texts and proceedings of the meetings were published in a series of pamphlets; the criteria for participation in the conferences were more clearly defined than in the original invitation and the subjects under debate became more focused on crucial questions such as the capitalist crisis, the role of revolutionaries, the question of national struggles, and so on. The debates also allowed groups who shared common perspectives to move closer together (as in the case of the CWO and Battaglia and the ICC and För Kommunismen in Sweden).

Despite these positive developments, however, the renascent revolutionary movement was burdened with many weaknesses inherited from the long period of counter-revolution.

For one thing, large numbers of those who could have been won to revolutionary politics were absorbed by the apparatus of leftism, which had also grown considerably in the wake of the class movements after 68. The Maoist and particularly the Trotskyist organizations were already formed and offered an apparently radical alternative to the ‘official’ Stalinist parties whose strike-breaking role in the Events of 68 and afterwards had been plain. Daniel Cohn-Bendit, “Danny the Red”, the feted student leader of 68, had written a book attacking the Communist Party’s function and proposing a “left wing alternative” which referred approvingly to the communist left of the 1920s and to councilist groups like ICO in the present[3]. But like so many others Cohn-Bendit lost patience with remaining in the small world of genuine revolutionaries and went off in search of more immediate solutions that also conveniently offered the possibility of a career, and today is a member of the German Greens who has served his party at the heart of the bourgeois state. His trajectory – from potentially revolutionary ideas to the dead-end of leftism – was followed by many thousands.

But some of biggest problems faced by the emerging milieu were “internal”, even if they ultimately reflected the pressure of bourgeois ideology on the proletarian political vanguard.

The groups which had maintained an organised existence during the period of counter-revolution – largely the groups of the Italian left – had become more or less sclerotic. The Bordigists of the various International Communist Parties[4] in particular had protected themselves against the perpetual rain of new theories that “transcended marxism” by turning marxism itself into an dogma, incapable of responding to new developments, as shown in their reaction to the class movements after 68 - essentially the one which Marx already derided in his letter to Ruge in 1843: here is the truth (the party), down on your knees! Inseparable from the Bordigist notion of the “invariance” of marxism was an extreme sectarianism[5] which rejected any notion of debate with other proletarian groups, an attitude concretised in the flat refusal of any of the Bordigist groups to engage with the international conferences of the communist left. But while the appeal by Battaglia was a small step away from the attitude of seeing your own small group as the sole guardian of revolutionary politics, it was by no means free of sectarianism itself: its invitation initially excluded the Bordigist groups and it was not sent to the ICC as a whole but to its section in France, betraying an unspoken idea that the revolutionary movement is made up of separate “franchises” in different countries (with Battaglia holding the Italian franchise of course).

Moreover sectarianism was not limited to the heirs of the Italian left. The discussions around regroupment in the UK were torpedoed by it. In particular, Workers Voice, frightened of losing its identity as a locally based group in Liverpool, broke off relations with the international tendency around RI and WR around the question of the state in the period of transition, which could only be an open question for revolutionaries who agreed on the essential class parameters of the debate. The same search for an excuse to break off discussions was subsequently adopted by RP and the CWO (product of a short-lived fusion of RP and WV) who declared the ICC to be counter-revolutionary because it did not accept that the Bolshevik party and the CI had lost all proletarian life from 1921 and not a moment later. The ICC was better armed against sectarianism because it traced its origins in the Italian Fraction and the GCF, who had always seen themselves as part of a wider proletarian political movement and not as the sole repository of truth. But the calling of the conferences had also exposed elements of sectarianism in its own ranks; some comrades initially responded to the appeal by declaring that the Bordigists and even Battaglia were not proletarian groups because of their ambiguities on the national question. Significantly, the subsequent debate about proletarian groups which led to a great deal of clarification in the ICC[6] was launched by a text by Marc Chirik who had been “trained” in the Italian and French left to understand that proletarian class consciousness is by no means homogeneous, even among the more politically advanced minorities, and that you could not determine the class nature of an organisation in isolation from its history and its response to major historical events, in particular world war and revolution.

With the new groups, these sect-like attitudes were less the product of a long process of sclerosis than of immaturity and the break in continuity with the traditions and organisations of the past. These groups were faced with the need to define themselves against the prevailing atmosphere of leftism, so that a kind of rigidity of thought often appeared to be a means of defence against the danger of being sucked under by the much larger organisations of the bourgeois left. And yet, at the same time, the rejection of Stalinism and Trotskyism often took the form of a flight into anarchist and councilist attitudes – manifested not only the tendency to reject the whole Bolshevik experience but also in a widespread suspicion of any talk about forming a proletarian party. More concretely, such approaches favoured federalist conceptions of organising, the equation of centralized forms of organization with bureaucracy and even Stalinism. The fact that many adherents of the new groups had come out of a student movement much more marked by the petty bourgeoisie than the student milieu of today reinforced these democratist and individualist ideas, most clearly expressed in the neo-Situationist slogan “militantism: the highest stage of alienation”[7]. The result of all this is that the revolutionary movement has spent decades struggling to understand the organisation question, and this lack of understanding has been at the heart of many conflicts and splits in the movement. Of course, the organisation question has of necessity been a constant battleground within the workers’ movement (witness the split between Marxists and Bakuninists in the First International, or between the Bolsheviks and the Mensheviks in Russia). But the problem in the re-emerging revolutionary movement at the end of the 60s was exacerbated by the long break in continuity with the organisations of the past, so that many of the lessons bequeathed by previous organisational struggles had to be re-learned almost from scratch.

It was essentially the inability of the milieu as a whole to overcome sectarianism that led to the blockage and eventual sabotage of the conferences[8]. From the beginning, the ICC had insisted that the conferences should not remain dumb but should, where possible, issue a minimum of joint statements, to make clear to the rest of the movement what points of agreement and disagreement had been reached, but also – faced with major international events like the class movement in Poland or the Russian invasion of Afghanistan – to make a common public statements around questions which were already essential criteria for the conferences, such as opposition to imperialist war. These proposals, supported by some, were rejected by Battaglia and the CWO on the grounds that it was “opportunist” to make joint statements when other differences remained. Similarly, when Munis and the FOR walked out of the second conference because they refused to discuss the question of the capitalist crisis, and in response to the ICC’s proposal to issue a joint criticism of the FOR’s sectarianism, BC simply rejected the idea that sectarianism was a problem: the FOR had left because it had different positions, so what’s the problem?

Clearly, underneath these divisions there were quite profound disagreements about what a proletarian culture of debate should be like, and matters reached a head when BC and the CWO suddenly introduced a new criterion for participation in the conferences – a formulation about the role of the party which contained ambiguities about its relationship to political power which they knew would not be acceptable to the ICC and which effectively excluded it. This exclusion was itself a concentrated expression of sectarianism, but it also showed that the other side of the coin of sectarianism is opportunism: on the one hand, because the new “hard” definition of the party did not prevent BC and the CWO holding a farcical 4th conference attended only by themselves and the Iranian leftists of the Unity of Communist Militants[9]; and on the other hand because, with the rapprochement between BC and the CWO, BC probably calculated that it had gained all it could from the conferences, a classic case of sacrificing the future of the movement for immediate gain. And the consequences of the break-up of the conferences have indeed been heavy – the loss of any organised framework for debate, for mutual solidarity, and an eventual common practice between the organisations of the communist left, which has never been restored despite occasional efforts towards joint work in subsequent years

The 1980s: crises in the milieu

The collapse of the conferences was soon revealed to be one aspect of a wider crisis in the proletarian milieu, expressed most clearly by the implosion of the Bordigist ICP and the “Chenier affair” in the ICC, which led to a number of members leaving the organisation, particularly in the UK.

The evolution of the main Bordigist organization, which published Programma Comunista in Italy and Le Proletaire in France (among others) confirmed the dangers of opportunism in the proletarian camp. The ICP had been growing steadily throughout the 70s and had probably become the largest left communist group in the world. And yet its growth had to a great extent been assured through the integration of a number of elements who had never really broken with leftism and nationalism. Certainly, the profound confusions of the ICP on the national question were not new: it claimed to defend the theses of the Second Congress of the Communist International on solidarity with revolts and bourgeois revolutions in the colonial regions. The CI theses would soon reveal themselves to be fatally flawed in themselves, but they did contain certain stipulations aimed at preserving the independence of communists in the face of rebellions led by national bourgeoisies in the colonies. The ICP had already taken some dangerous steps away from such safeguards, for example when it hailed the Stalinist terror in Cambodia as an example of the necessary vigour of a bourgeois revolution[10]. But the sections in North Africa organised around the paper El Oumami went even further than this, since in the face of the military conflicts in the Middle East it openly called for defence of the Syrian state against Israel. This was the first time that any Bordigist group had brazenly called for participation in a war between capitalist states. It is significant that there were strong reactions within the ICP against these positions, testifying to the fact that the organisation retained its proletarian character, but the end result was further splits, the departure of whole sections and of many individual militants, reducing the survivors of the shipwreck to small nuclei who have never been able to draw all the lessons from these events.

But an opportunist tendency also appeared in the ICC at the time – a grouping which, in response to the class struggles of the late 70s and early 80s, began to make serious concessions to rank and file trade unionism. But the problem posed by this grouping was situated above all at the organisational level, since it began to question the centralised nature of the ICC and to argue that central organs should function mainly as letter boxes rather than as bodies elected to provide political orientation in between general meetings and congresses. This did not imply that the grouping was held together by a deep programmatic unity. In reality it was held together by affiliations based on personal relationships and common resentments against the organisation – in other words, it was a secretive “clan” rather than a real tendency, and in an immature organisation it gave rise to a “counter-clan” in the UK section, with disastrous results. And stirring up these resentments and conflicts was the dubious element Chenier, who had a past history of travelling through revolutionary organisations and fomenting crises, and who engaged in the most shameful manipulation of those around him. The crisis came to a head in the summer of 1981 when members of the “tendency” entered a comrade’s house when he was away and stole equipment from the organisation on the spurious grounds that they were only cashing in the investment they had made in the organisation. The tendency formed a new group which folded after a single issue, and Chenier “returned” to the Socialist Party and the CFDT, for whom he had probably been working all along, most likely in the “Secteur des Associations” which monitors the development of currents to the left of the PS.

This split was met with a very uneven response from the ICC as a whole, especially after the organisation made a determined attempt to get its stolen equipment back by visiting the houses of those suspected of being involved in the thefts and demanding the equipment be returned. A number of comrades in the UK simply left the organisation, unable to cope with the realisation that a revolutionary organisation has to defend itself in this society, and that this can include physical action as well as political propaganda. The Aberdeen/Edinburgh sections not only quickly departed, but publicly denounced the ICC’s actions and threatened to call the police if they were subject to any visits themselves (since they also retained a certain amount of material belonging to the organisation, even though to our knowledge they had not been directly involved in the initial thefts). And when the ICC issued a very necessary public warning about the activities of Chenier, they rushed to defend his honour. This was the inglorious beginning of the Communist Bulletin group, whose publications were largely dedicated to attacks on the Stalinism and even the insanity of the ICC. In short, this was an early example of political parasitism which was to become a significant phenomenon in the subsequent decades[11]. Within the wider proletarian milieu, there were few if any expressions of solidarity with the ICC. On the contrary, the CBG’s version of the events is still circulating on the internet and has a strong influence, on the anarchist milieu in particular.

We can point to further expressions of crisis in the years that followed. The balance sheet of the groups who took part in the international conferences is mainly negative: disappearance of groups that had only recently broken with leftism (L’Eveil Internationaliste, the OCRIA, Marxist Workers Group in the USA)) Others were pulled in the opposite direction: the NCI, a split with the Bordigists which had shown a certain level of maturity on organisational questions during the conferences, fused with the Il Leninsta group and followed it to abandon internationalism and adopt a more or less open form of leftism (the OCI)[12]. The Groupe Communiste Internationaliste, which had come to the third conference merely to denounce it, already expressing its destructive and parasitic character, began to adopt openly reactionary positions (support for Peruvian Maoists and El Salvador guerillas, culminating in a grotesque justification for the actions of the “centrist” al Qaida and physical threats against the ICC in Mexico[13]). The GCI, whatever its motivations, is a group which essentially does the work of the police, not only by threatening violence against proletarian organisations, but also by giving the impression that there is a link between authentic communist groups and the shady milieu of terrorism.

In 1984 we also saw the formation of International Bureau for the Revolutionary Party, a coming together of the CWO and Battaglia. The IBRP (now the ICT) has maintained itself on an internationalist terrain, but the regroupment was in our view achieved on an opportunist basis – a federalist conception of national groups, a lack of open debate about the differences between them, and series of hasty attempts to integrate new sections which would in most cases end in failure.[14]

1984-5 saw the split in the ICC which gave rise to the “External Fraction of the ICC”. The EFICC initially claimed to be the true defenders of the ICC’s platform against alleged deviations on class consciousness, the existence of opportunism in the workers’ movement, the alleged monolithism and even “Stalinism” of our central organs etc. In reality, the whole approach of the ICC was jettisoned very rapidly, showing that the EFICC was not what it thought it was: a real fraction fighting the degeneration of the original organisation. In our view, this was another clan formation which put personal links above the needs of the organisation, and whose activity once leaving the ICC provided another example of political parasitism[15].

The proletariat, according to Marx, is a class of civil society which is not a class of civil society – part of capitalism and yet in a sense alien to it[16]. And the proletarian organisation, which above all embodies the communist future of the working class, is no less a foreign body for being part of the proletariat. Like the proletariat as a whole, it is subject to the constant pressure of bourgeois ideology, and it is this pressure, or rather the temptation to adapt to it, to conciliate with it, which is the source of opportunism. It is also the reason why revolutionary organisations cannot live a “peaceful” life within capitalist society and are inevitably doomed to go through crises and splits, as conflicts break out between the proletarian “soul” of the organization and those who have succumbed to the ideologies of other social classes. The history of Bolshevism, for example, is also a history of organisational struggles. Revolutionaries do not seek or advocate crises, but when they do break out, it is essential to mobilise its forces to defend its central principles if they are being undermined, and to fight for clarification of the divergences and their roots instead of running away from these obligations. And of course it is vital to learn the lessons that these crises inevitably bring with them, in order to make the organisation more resistant in the future.

For the ICC, crises have been frequent and sometimes very damaging, but they have not always been entirely negative. Thus the 1981 crisis, following an extraordinary conference in 1982, led to the elaboration of fundamental texts on both the function and the mode of functioning of revolutionary organisations in this epoch[17], and brought vital lessons on the permanent necessity for a revolutionary organisation to defend itself, not only against the direct repression of the bourgeois state, but also against dubious or hostile elements who pose as part of the revolutionary movement and may even infiltrate its organisations.

Similarly the crisis that led to the departure of the EFICC saw a maturation of the ICC on a range of key issues: the real existence of opportunism and centrism as diseases of the workers’ movement; the rejection of councilist visions of class consciousness as being purely a product of the immediate struggle (and hence the necessity for the revolutionary organisation as the main expression of the historic, depth dimension of class consciousness); and, linked to this, the understanding of the revolutionary organisation as an organisation of combat, capable of intervening in the class at several levels: not only theoretical and propagandistic, but also agitational, providing orientations for the extension and self-organisation of the struggle, participating actively in general assemblies and struggle groups.

Despite the clarifications that the ICC made by responding to its internal crises, they did not guarantee that the organisation problem, in particular, was now solved and that there would be no more cases of falling back into error. But at the very least, the ICC recognized that the question of organisation was a political question in its own right. On the other hand, the milieu in general didn’t see the importance of the organisational issue. “Anti-Leninists” of various stripes (anarchists, councilists, modernists, etc) saw the very attempt to maintain a centralised organization as inherently Stalinist, while the Bordigists made the fatal mistake of thinking that the last word had been said on the question and that there was nothing further to discuss. The IBRP was less dogmatic but tended to treat the organisation question as secondary. For example, in their response to the crisis which hit the ICC in the mid-90s, they did not deal with the organisational issues at all but argued that they were essentially a by-product of the ICC’s mistaken evaluation of the balance of class forces.

There is no doubt that an incorrect appreciation of the world situation can be an important factor in organisational crises: in the history of the communist left, for example, we can point to the adoption, by a majority of the Italian Fraction, of Vercesi’s theory of the war economy, which considered that the accelerating march towards war in the late 30s was proof that the revolution was imminent. The outbreak of the imperialist war thus saw a total disarray in the Fraction.

Similarly, the tendency of the groups coming out of the 68 upsurge to overestimate the class struggle, to see the revolution as “just around the corner”, meant that the growth of revolutionary forces in the 70s was extremely fragile: many of those who joined the ICC at that time did not have the patience and conviction to last the course when it became clear that the struggle for revolution was one posed in the long term and that the revolutionary organisation would be engaged in a permanent struggle for survival, even when the class struggle was globally following an upward course. But the difficulties resulting from this immediatist vision of world events also had a major organisational element: not only in the fact that during that period members were often integrated in a hasty, superficial manner, but above all in the fact that they were integrated into an organisation which did not yet have a clear vision of its function, which was not to act as if it was already a kind of mini-party but was above all to see itself as a bridge to the future communist party. The revolutionary organisation in the period that began in 1968 thus retained many features of a communist fraction even if it had no direct organic continuity with the parties or fractions of the past. This does not at all mean that we should have renounced the task of direct intervention in the class struggle. On the contrary, we have already argued that one of the key components in the debate with the tendency that formed the “External Fraction” was precisely the insistence on the need for a communist intervention in the struggles of the class – a task which may vary in scope and intensity, but which never disappears, in different phases of the class struggle. But it does mean that the largest part of our energies have necessarily been focused on the defence and construction of the organisation, to analysing a rapidly evolving world situation and both preserving and elaborating our theoretical acquisitions. This focus would become even more important in the conditions of the phase of social decomposition from the 1990s onwards, which have powerfully increased the pressures and dangers confronting revolutionary organisations, We will examine the impact of this phase in the second part this article.

Amos

Annex

Introductory note to the pamphlets containing the texts and proceedings of the Second International Conference of Groups of the Communist Left, 1978, written by the international technical committee:

“With this first pamphlet we are beginning the publication of the texts of the Second International Conference of the groups of the Communist left, held in Paris on 11 and 12 November 1978 on the initiative of the Internationalist Communist Party, Battaglia Comunista. The texts of the First International Conference, held in Milan on 30 April and I May 1977, were published in Italian under the responsibility of the ICP/BC and in French and English under the responsibility of the ICC.

On 30 June, 1977, the ICP/BC, in accordance with what had been decided at the Milan Conference and subsequent contacts with the ICC and CWO, sent out a circular letter inviting the following groups to a new conference to be held in Paris:

International Communist Current (France, Belgium, Britain, Spain, Italy, Germany. Holland, USA, Venezuela)

Communist Workers Organisation (Britain)

International Communist Party (Communist Programme: Italy, France, etc)

Il Leninista (Italy)

Nucleo Comunista Internazionalista (Italy)

Iniziativa Comunista (Italy)

Fomento Obrero Revolucionario (France, Spain)

Pour Une Intervention Communiste (France)

Forbundet Arbetarmakt (Sweden)

För Komunismen (Sweden)

Organisation Communiste Revolutionaire Internationalise d’Algerie

Kakamaru Ha (Japan)

Partito Comunista Internazionale/Il Partito Comunista (Italy)

Spartakusbond (Holland)

In volume II we will publish this letter

Of the groups invited, Spartakusbond and Kakamaru Ha didn’t reply

Communist Programme and Il Partito Comunista refused to participate in articles appearing in their respective publications. Both rejected the spirit of the initiative as well as the political content of the work itself (particularly on the party and national liberation wars)

The PIC refused with a letter-document to participate in a meeting based on a recognition of the first two congresses of the Third International, which they see as being essentially social democratic from the beginning (see Vol II).

Forbundet Arbetarmakt rejected the invitation since it doubted that it could recognize the criteria for participation (see Vol II)

Iniziativa Comunista gave no written response, and at the last minute – after having agreed to come to a joint meeting of Battaglia and Il Leninista – refused to participate in the conference, justifying its attitude in the issue of its bulletin which appeared after the Paris conference.

Il Leninista. Although it confirmed its agreement to participate, was unable to attend due to technical problems at the time they set off for the meeting

The OCRIA of the Algerian immigrants in France was unable to participate physically in the meeting for security reasons, but asked to be considered as a participating group

The FOR, although it had participated at the beginning of the conference – to which it presented itself as an observer at the sidelines – quickly dissociated itself from the conference, saying that its presence was incompatible with groups who recognize that there is now a structural crisis of capital (see vol II)……”

In between the second and third conferences, the Swedish group För Komunismen had become the ICC section in Sweden and Il Nucleo and Il Leninista had fused to become a single organsiation, Il Nuclei Leninisti

The list of participating groups was:

ICC, Battaglia, CWO, Groupe Communiste Internationaliste, L’Éveil Internationaliste, Il Nuclei Leninisti OCRIA, which sent written contributions. The American Marxist Workers’ Group associated itself to the conference and would have sent a delegate, but was prevented from doing so at the last minute.

[1] Published in Internationalism 4, undated, but circa 1973

[2] For a list of the groups who attended or supported conferences, see the annex

[3] Obsolete Communism, the Left wing Alternative, Penguin 1969

[4] These groups all had their origin in the 1952 split within the Internationalist Communist Party in Italy. The group around Damen retained the name Internationalist Communist Party; the “Bordigists” took the name International Communist Party, which after further splits now has several incarnations under the same name.

[5] Sectarianism was a problem already identified by Marx when he wrote: “The sect sees the justification for its existence and its point of honour not in what it has in common with the class movement but in the particular shibboleth which distinguishes it from the movement.” Of course, such formulae can be mis-used if taken out of context. For the left wing of capital, the entire communist left is sectarian because it does not consider itself to be part of what they call the “labour movement” – organisations like the unions and social democratic parties whose class nature has changed since Marx’s day. From our point of view, sectarianism today is problem between proletarian organisations. It is not sectarian to reject premature fusions or adherence that cover over real disagreements. But is certainly sectarian to reject all discussion between proletarian groups or to dismiss the need for basic solidarity between them.

[6] This debate gave rise to a resolution on proletarian political groups at the Second ICC Congress (see IR 11: https://en.internationalism.org/content/4091/resolution-proletarian-poli...)

[7] Ref: https://libcom.org/library/militancy-ojtr The early 70s also saw the rise of “modernist” groups who began to cast doubt on the revolutionary potential of the working class and who tended to see political organisations, even when they clearly stood for the communist revolution, as no more than rackets. Cf the writings of Jacques Camatte. These were the forebears of today’s “communisation” tendency. A number of the groups contacted by Internationalism in 1973 went off in this direction and were irretrievably lost: Mouvement Communiste in France (not the existing autonomist group, but the group around Barrot/ Dauvé which had initially made a written contribution to the Liverpool meeting), Komunisimen in Sweden, and in a certain sense Solidarity UK, which shared with these other groups the enormous conceit of having gone beyond marxism.

[9] An early expression of the “Hekmatist” tendency which today exists in the shape of the Worker Communist Parties of Iran and Iraq – a tendency which is still often described as left communist but is in fact a radical form of Stalinism. See our article “The Worker Communist Parties of Iran and Iraq: the dangers of radical Stalinism”. https://en.internationalism.org/wr/293_wpiran.html.

[10] IR 28.’The present convulsions in the revolutionary milieu’, https://en.internationalism.org/node/3116; also IR 32https://en.internationalism.org/node/3123

[11]https://en.internationalism.org/content/3667/political-parasitism-cbg-do... We will return to the problem of political parasitism in the second part of the article

[12]Organizzazione Comunista Internazionalista

[14] See IR 121: “IBRP: an opportunist policy of regroupment that leads to nothing but ‘abortions’” https://en.internationalism.org/ir/121_ibrp

[15] See “The ‘External Fraction’ of the ICC”, in IR 45: https://en.internationalism.org/ir/45_eficc

[16] In the introduction to A Contribution to the Critique of Hegel’s Philosophy of Right

[17] See the two reports on the organisation question from the 1982 Extraordinary Conference: on the function of the revolutionary organization (IR 29) and on its structure and method of functioning (IR 33)

del.icio.us

del.icio.us Digg

Digg Newskicks

Newskicks Ping This!

Ping This! Favorite on Technorati

Favorite on Technorati Blinklist

Blinklist Furl

Furl Mister Wong

Mister Wong Mixx

Mixx Newsvine

Newsvine StumbleUpon

StumbleUpon Viadeo

Viadeo Icerocket

Icerocket Yahoo

Yahoo identi.ca

identi.ca Google+

Google+ Reddit

Reddit SlashDot

SlashDot Twitter

Twitter Box

Box Diigo

Diigo Facebook

Facebook Google

Google LinkedIn

LinkedIn MySpace

MySpace