Submitted by International Review on

Part One: programme and practice

The previous article in the series took us into the work of the revolutionary movement as it emerged from the catastrophe of the Second World War. We showed how, despite this catastrophe, the best elements in the marxist movement continued to hold on to the perspective of communism. Their conviction in this perspective had not faded even though the world war had not, as many revolutionaries had predicted, provoked a new upsurge of the proletariat against capitalism, and had indeed deepened the already terrible defeat that had descended on the working class during the 1920s and 30s. We focused in particular on the work of the Gauche Communiste de France, which was probably the only organisation to understand that the tasks of the hour remained those of a fraction, of preserving and deepening the theoretical acquisitions of marxism in order to construct a bridge to future proletarian movements which would create the conditions for the reconstitution of a real communist party. This had been the project of the Italian and Belgian left fractions before the war, although a significant part of this International Communist Left had lost sight of this in the short-lived euphoria of the revival of workers’ struggles in Italy in 1943 and the declaration of the Internationalist Communist Party in Italy.

The previous article in the series took us into the work of the revolutionary movement as it emerged from the catastrophe of the Second World War. We showed how, despite this catastrophe, the best elements in the marxist movement continued to hold on to the perspective of communism. Their conviction in this perspective had not faded even though the world war had not, as many revolutionaries had predicted, provoked a new upsurge of the proletariat against capitalism, and had indeed deepened the already terrible defeat that had descended on the working class during the 1920s and 30s. We focused in particular on the work of the Gauche Communiste de France, which was probably the only organisation to understand that the tasks of the hour remained those of a fraction, of preserving and deepening the theoretical acquisitions of marxism in order to construct a bridge to future proletarian movements which would create the conditions for the reconstitution of a real communist party. This had been the project of the Italian and Belgian left fractions before the war, although a significant part of this International Communist Left had lost sight of this in the short-lived euphoria of the revival of workers’ struggles in Italy in 1943 and the declaration of the Internationalist Communist Party in Italy.

As part of this effort to build on the work of the pre-war left fractions, the GCF had carried on the work of drawing the lessons of the Russian revolution and of examining the problems of the transitional period: the dictatorship of the proletariat, the transitional state, the role of the party, and the elimination of the capitalist mode of production. We therefore republished and introduced the GCF’s theses on the role of the state, which would serve as the basis for future debates on the period of transition within the renascent revolutionary milieu of the early 1970s.

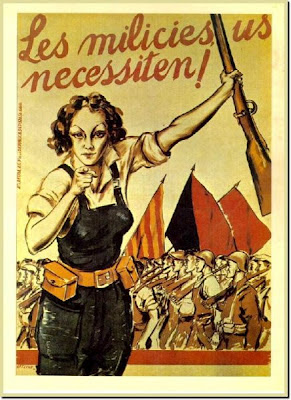

But before proceeding to a survey of those debates, we need to take a historical step back – to a major landmark in the history of the workers’ movement: Spain 1936-37. As we shall argue, we are not among those who see these events as providing us with a model of proletarian revolution which goes far deeper than anything achieved in Russia in 1917-21. But there is no question that the war in Spain has taught us a great deal, even if most of its lessons are negative ones. In particular, it offers us a very sharp insight into the inadequacies of the anarchist vision of the revolution and a striking reaffirmation of the vision that has been preserved and developed by the authentic traditions of marxism. This is particularly important to affirm given the fact that over the last few decades these traditions are frequently derided as being out of date and unfashionable, and that, among the politicised minority of the current generation, anarchist ideas in various forms have gained an undeniable influence.

This series has always been premised on the conviction that marxism alone provides a coherent method for understanding what communism is and why it is necessary, and for mining the historical experience of the working class for evidence that it is also a real possibility and not a mere wish for a better world. This is why such a large part of this series has been taken up with the study of the advances and the errors made by the marxist wing of the workers’ movement in its effort to comprehend and elaborate the communist programme. For the same reason, it is only at certain moments that it has looked at the attempts of the anarchist movement to work out its notion of the future society. In the article ‘Anarchism or communism’ (volume one of the present series, in International Review 79) we pointed out that at the historic origins of the anarchist vision lay the resistance of petty bourgeois strata such as the artisans and small peasants to the process of proletarianisation, which was an inevitable product of the emergence and expansion of the capitalist mode of production. Although a number of anarchist currents are clearly part of the workers’ movement, none of them have succeeded in entirely effacing these petty bourgeois birthmarks. The article in IR 79 demonstrates how, in the period of the First International, this essentially backward-looking ideology was behind the resistance of the clan around Bakunin to the theoretical gains of marxism at three crucial levels: in its conception of the organisation of revolutionaries, which was deeply infected by the conspiratorial methods of outmoded sects; in its rejection of historical materialism in favour of a voluntarist and idealist assessment of the possibilities of revolution; and in its conception of the future society, seen as a network of autonomous communes linked by commodity exchange.

Nevertheless, with the development of the workers’ movement in the latter part of the 19th century, the most important trends in anarchism tended to become more firmly integrated into the struggle of the proletariat and its perspective for a new society, and this was particularly true of the anarcho-syndicalist current (although, simultaneously, the dimension of anarchism as a manifestation of petty bourgeois rebellion was kept alive in the ‘exemplary acts’ of the Bonnot gang and others)1.The reality of this proletarian trend was demonstrated in the capacity of certain anarchist currents to take up internationalist positions faced with the First World War (and to a lesser extent the Second), and in the will to develop a clearer programme for their movement. The period from the late 19th century to the 1930s thus saw various attempts to develop documents and platforms which could be a guide to the establishment of ‘libertarian communism’ through social revolution. An obvious example of this was Kroptotkin’s The Conquest of Bread, which first appeared as an integral work in French in 1892 and was published over a decade later in English2. Despite Kropotkin’s abandonment of internationalism in 1914, this and other writings by him are part of the classical canon of anarchism and deserve a much more developed critique than is possible in this article.

In 1926 Makhno, Arshinov and others published the Platform of the General Union of Anarchists3. This is the founding document of the ‘platformist’ current in anarchism, and it too calls for a more thorough examination, along with an analysis of the historical trajectory of platformism from the late 1920s to the present. Its principal interest lies in the conclusions it draws from the failure of the anarchist movement in the Russian revolution, notably the idea that anarchist revolutionaries need to regroup in their own political organisation, based on a clear programme for the establishment of the new society. It was this idea in particular that drew the fire of other anarchists – not least Voline and Malatesta - who saw it as expressing a kind of anarcho-Bolshevism.

In this article, however, we are most concerned with the theory and practice of the anarcho-syndicalist tendency during the 1930s. And here again there is no dearth of material. In our most recent series on the decadence of capitalism published in this Review, we mentioned the text by the exiled Russian anarcho-syndicalist Gregory Maximoff, My Social Credo. Written in the depth of the Great Depression, it showed a remarkable degree of clarity about the decadence of the capitalist system, something almost never displayed by the anarchists of today4. The text also contains a section outlining Maximoff’s ideas about the organisation of the new society. During this period there were also significant debates about how to get from capitalism to libertarian communism within the anarcho-syndicalist ‘International’ established in 1922, the International Workers’ Association. And probably most relevant of all was Isaac Puente’s pamphlet ‘Libertarian Communism’. Published in 1932, it was to serve as the basis for the CNT’s platform at the 1936 Zaragoza Congress, and can thus be considered as a factor influencing the policies of the CNT during the ensuing ‘Spanish revolution’. We will come back to this, but first we want to look at some of the debates in the IWA, which are brought to light in Vadim Damier’s very informative work Anarcho-syndicalism in the 20th century5

One of the key debates – no doubt in reaction to the spectacular rise of Fordist/Taylorist mass production techniques in the 1920s – was centred on the question of whether or not this kind of capitalist rationalisation, and indeed the whole process of industrialisation, was an expression of progress, making a libertarian communist society a more tangible perspective, or merely an intensification of humanity’s enslavement by the machine. Different tendencies brought different nuances to this discussion, but broadly speaking the split was between the anarcho-communists who took the latter view and connected their stance with a call for an immediate transition to communism; this was seen as being possible even - or perhaps especially – in a predominantly agrarian society. The alternative position was more generally held by tendencies connected to the revolutionary syndicalist tradition, who took a more ‘realistic’ view of the possibilities offered by capitalist rationalisation while at the same time arguing that there would have to be some kind of transitional economic regime in which monetary forms would continue to exist.

These divergences traversed various national sections (such as the German FAUD), but the Argentine FORA6 seems to have had a more unified view which they defended with some conviction, and they were at the forefront of the ‘anti-industrialist’ outlook. They openly rejected the premises of historical materialism, at least as they saw it (for most of the anarchists ‘marxism’ was a catch-all term defining everyone from Stalinism and Social Democracy to Trotskyism and left communism) in favour of a view of history in which ethics and ideas were no less significant than the development of the productive forces. They categorically rejected the idea that the new society could be formed on the basis of the old, which is why they criticised not only the project of building libertarian communism on the foundations of the existing industrial structure, but also the syndicalist project of organising workers in industrial unions that would, come the revolution, take over this structure and wield it on behalf of the proletariat and humanity. They envisaged a new society organised in a federation of free communes; the revolution would be a radical break with all the old forms and would proceed immediately to the stage of free association. A declaration from the 5th Congress of the FORA in 1905 – which according to Eduardo Columbo’s account was to become the basic policy for many years – outlined the FORA’s criticisms of the union form:

“We must not forget that a union is merely an economic by-product of the capitalist system, born from the needs of this epoch. To preserve it after the revolution would imply preserving the system which gave rise to it. The so-called doctrine of revolutionary syndicalism is a fiction. We, as anarchists, accept the unions as weapons in the struggle and we try to ensure that they should approximate as closely as possible to our revolutionary ideals...That is to say, we do not intend to be mentally dominated by the unions; we intend to dominate them. In other words, to make the unions serve the propagation, the defence, and the affirmation of our ideas among the proletariat”7

However, the differences between the ‘Forists’ and the syndicalists on the union form remained rather obscure in many ways: on the one hand, the FORA saw itself as an organisation of anarchist workers rather than a union “for all workers” but at the same time it emerged and developed as a union-type formation that organised strikes and other forms of class action.

Despite the unclear nature of these divergences, they led to heated clashes at the 4th Congress of the IWA in Madrid in 1931, with the two approaches being defended mainly by the French CGT-SR8 on the one hand and the FORA on the other. Damier makes the following remarks about the FORA’s views:

“The conceptions of the FORA contained a critique of the alien and destructive character of the industrial-capitalist system which was brilliant for its time – the FORA’s proposals anticipated by half a century the recommendations and prescriptions of the contemporary ecological movement. Nevertheless their critique had a point of vulnerability – a categorical refusal to elaborate more concrete notions about the future society, how to get to it and how to prepare for it. According to the thinking of the Argentine theoreticians, to do so would be to infringe on revolutionary spontaneity and the improvisations of the masses themselves. The achievement of socialism was not a matter of technical and organisational preparation, but rather the dissemination of feelings of freedom, equality and solidarity – insisted the Argentine worker-anarchists”(pp110-111).

The FORA’s insights into the nature of capitalist social relations – like those into the trade union form – are certainly interesting, but what strikes one most about these debates is their flawed starting point, their lack of method flowing from the rejection of marxism or even any willingness to discuss with the authentic marxist currents of the day. The FORA’s criticism of historical materialism looks more like a criticism of a rigidly deterministic version of marxism, typical of the Second International and the Stalinist parties. Again, they were right to attack the alienated nature of capitalist production and to repudiate the idea that capitalism was progressive in itself - above all in a period where capitalist social relations had already proved themselves to be a fundamental obstacle to human development - but their apparent rejection of industry as such was equally abstract and resulted in a backward-looking nostalgia for localised rural communes.

Perhaps more significant was the lack of any connection between these debates and the most important experiences of the class struggle in the new epoch inaugurated by the mass strikes in Russia in 1905 and the international revolutionary wave of 1917-23. These world-historic developments, which also of course included the first world imperialist war, had already demonstrated the obsolescence of the old forms of workers’ organisation (mass parties and trade unions)and given rise to new ones: the soviets or workers’ councils on the one hand, formed in the heat of the struggle rather than as a pre-existing structure, and the organisation of the communist minority, no longer seen as a mass party acting primarily on the terrain of the struggle for reforms, on the other. The formation of revolutionary or industrial trade unions in the last part of the 19th century and in the decades that followed was to a large extent an attempt by a radical fraction of the proletariat to attempt to adapt to the new epoch without really abandoning the old trade unionist (and even social democratic) conceptions of incrementally building up a mass workers’ organisation inside capitalism, with the ultimate aim of taking control of society in a phase of acute crisis. The FORA’s suspicion of the idea of building the new society in the shell of the old was justified. However, without any serious reference to the experience of the mass strike and the revolution, whose essential dynamic had been brilliantly analysed by Rosa Luxemburg in The Mass Strike, the Political Party and the Trade Unions, written in 1906, or to the new forms of organisation which Trotsky, for example, had recognised as a crucially important product of the 1905 revolution in Russia, the FORA fell back into a diffuse hope of a sudden and total transformation and seemed unable to examine the real links between the defensive struggles of the proletariat and the struggle for revolution.

Isaac Puente’s ‘Libertarian Communism’ pamphlet

In the 1931 debates the majority of the Spanish CNT sided with the more traditional anarcho-syndicalists. But ‘communitarian’ ideas persisted and the 1936 Zaragoza programme, based on Puente’s pamphlet, contained elements of both.

Puente’s pamphlet9 clearly expresses a proletarian standpoint and its ultimate aim – ‘libertarian’ communism – is what we would simply call communism, a society based on the principle, as Puente puts it, “from each according to his/her abilities, to each according to his/her needs”. At the same time, it is a rather clear manifestation of the theoretical poverty at the heart of the anarchist world-view.

A long section at the beginning of the text is devoted to arguing against all prejudices which argue that the workers are ignorant and stupid, incapable of emancipating themselves, contemptuous of science, art and culture, that they need an intellectual elite, a “social architect”, or a police power to run society on their behalf. This polemic is perfectly justified. And yet when he writes that “what we call common sense, a quick grasp of things, intuitive ability, initiative and originality are not things that can be bought or sold in the universities”, we are reminded of the fact that revolutionary theory is not simple common sense, that its propositions, being dialectical, are generally seen as outrageous and nonsensical from the viewpoint of the ‘good old common sense’ which Engels ridiculed in Anti-Dühring 10. The working class does not need educators from on high to free itself of capitalism, but it does need a revolutionary theory that can go beyond mere appearance and understand the deeper processes at work in society.

Anarchism’s inadequacies at this level are revealed in all the principal theses put forward in Puente’s text. Regarding the forms that the working class will use to confront and overthrow capitalism, like the debates in the IWA at the time, Puente ignores the whole dynamic of the class struggle in the epoch of revolution, brought to the surface by the mass strike and the emergence of the council form. Instead of seeing that the organisations that will carry out the communist transformation express a radical rupture with the old class organisations that have been incorporated into bourgeois society, Puente insists that “libertarian communism is based on organisations that already exist, thanks to which economic life in the cities and villages can be carried on in the light of the particular needs of each locality. Those organisms are the union and the free municipality”. This is where Puente combines syndicalism with communitarianism: in the cities, the syndicates will take control of public life, in the countryside it will be the traditional village assemblies. The activities of these organs are envisaged mainly in local terms: they can also federate and form national structures where necessary, but Puente sees the surplus product of local economic units being exchanged with that of others. In other words, this libertarian communism can co-exist with value relations, and it is not clear whether this is a transitional measure or something that will exist in perpetuity.

Meanwhile, this transformation takes place through “direct action” and not through any engagement in the sphere of politics, which is entirely identified with the existing state. In a comparative chart between “organisation based on politics, which is a feature common to all regimes based on the state, and organisations based on economics, in a regime which shuns the state”, Puente draws out the hierarchical and exploitative character of the state and opposes to it the democratic life of the unions and free municipalities, based on decisions reached by assemblies and on common needs. There are two fundamental problems with this approach: first of all, it fails entirely to explain that the unions – and this was even to include anarcho-syndicalist unions like the CNT - have never been models of self-organisation or democracy but are subjected to a powerful pressure to integrate themselves into capitalist society, to themselves become bureaucratic institutions that tend to merge with the state. And secondly it ignores the reality of revolution, in which the working class is necessarily faced with a nexus of problems which are unavoidably political: the organisational and theoretical autonomy of the working class from the parties and ideologies of the bourgeoisie, the destruction of the capitalist state, and the consolidation of its own organs of power. These deep lacunae in the libertarian programme were to be brutally exposed by the reality of the war that broke out in Spain soon after the Zaragoza Congress.

But there is another and no less decisive problem: the text’s failure to consider the international dimension, and indeed its narrowly national outlook. It’s true that the first of many “prejudices” refuted in the text is “the belief that the crisis is merely temporary”. Like Maximoff, the Great Depression of the 30s seems to have convinced Puente that capitalism was a system in decline, and the paragraph under this sub-heading at least has something of a global ring to it, mentioning the situation of the working class in Italy and in Russia. But there is no attempt whatever to assess the balance of class forces, a primordial task for revolutionaries after a period of a mere 20 years which had seen world war, an international revolutionary wave, and series of catastrophic defeats for the proletariat. And when it comes to examining the potential for libertarian communism in Spain, it is almost as if the outside world does not exist: there is a long section given over to estimating the economic resources of Spain, down to its oranges and potatoes, its cotton, timber, and oil. The whole aim of these calculations is to show that Spain could exist as a self-sufficient island of libertarian communism. Certainly Puente considers that “the introduction of libertarian communism in our country, alone of the nations of Europe, will bring with it the hostility of the capitalist nations. Using the defence of its subjects’ interests as a pretext, bourgeois imperialism will attempt to intervene by force of arms to crush our system at its birth”. But such intervention will be hampered by the threat that it will provoke either social revolution in the intervening power or world war against other powers. The foreign capitalists might therefore prefer to employ mercenary armies rather than their own armies, as they did in Russia: in either case the workers will have to be ready to defend their revolution arms in hand. But the other bourgeois states might also seek to impose an economic blockade, backed up by warships. And this could be a real problem because Spain lacks some crucial resources, in particular petroleum, and would normally be obliged to import it. The solution to a blockade on imports however, is not hard to find: “it would be vital that we pour all our energies into sinking new wells in search of petroleum...petroleum may (also) be obtained by distilling soft coal and lignite, both of which we have in abundance in this country”.

In sum: to create libertarian communism, Spain must become autarchic. It is a pure vision of anarchy in one country11. This inability to begin from the standpoint of the world proletariat would become another fatal flaw when Spain became the theatre of a global imperialist conflict.

The events of 36-37: social revolution or imperialist war?

The anarcho—syndicalist model of revolution as expounded in Puente’s text and the Zaragoza programme was to be definitively exposed and refuted by the momentous historic events sparked off by Franco’s military coup in July 1936.

This is certainly not the place to write a blow by blow account of these events. We can only limit ourselves to recalling their overall pattern, with the aim of reaffirming the view of the communist left at the time: that the congenital incoherence of anarchist ideology had now become a vehicle for the betrayal of the working class.

There is no better analysis of the first moments of the war in Spain than the article published in the journal of the Italian Left Fraction, Bilan 36, October-November 1936, and republished in International Review 6. Written almost immediately after the events, and no doubt after sifting through a mass of very confused and confusing information, it is remarkable how the comrades of Bilan managed to slice through the dense fog of mystifications surrounding the ‘Spanish revolution’, whether in the version that was most publicised at the time by the powerful media controlled by democrats and Stalinists– as a kind of bourgeois democratic revolution against the feudal-fascist reaction – or the picture painted by the anarchists and Trotskyists, which, while presenting the struggle in Spain as a social revolution that had gone much further than anything achieved in Russia in 1917, also served to reinforce the dominant view of the struggle as a people’s barrier against the advance of fascism in Europe.

The Bilan article recognises without hesitation that, faced with the attack from the right, the working class, above all in its Barcelona stronghold, responded with its own class weapons: the spontaneous mass strike, street demonstrations, fraternisation with the soldiers, the general arming of the workers, the formation of neighbourhood based defence committees and militias, the occupation of the factories and the election of factory committees. Bilan also recognised that it was the militants of the CNT-FAI who had everywhere played a leading role in this movement, which, however, had embraced the majority of the working class of Barcelona.

And yet it was precisely at this moment, when the working class was on the brink of taking political power into its own hands, that anarchism’s programmatic weaknesses, its theoretical inadequacy, were to prove a deadly handicap.

First and foremost, anarchism’s failure to understand the problem of the state led it not only to quaver at the possibility of a proletarian dictatorship – because anarchism is ‘against all kinds of dictatorship’ – but perhaps even more crucially, it was utterly disarmed in the face of the manoeuvres of the ruling class, which was able to reconstitute a state power with new and ‘radical’ forms, given that its more traditional forces had been paralysed by the proletarian upsurge. Key instruments in this process were the Central Committee of the Anti-Fascist Militias and the Central Council of the Economy:

“The constitution of the Central Committee of the Militias gave the impression that a period of proletarian power had begun; while the setting up of the Central Council of the Economy gave rise to the illusion that the proletariat was now managing its own economy.

However, far from being organs of dual power, these organs had a capitalist nature and function. Instead of constituting a base for the unification of the proletarian struggle – for posing the question of power – they were from the beginning organs of collaboration with the capitalist state.

In Barcelona the Central Committee of the militias was a conglomeration of workers’ and bourgeois parties and trade unions; not an organ of the soviet type arising spontaneously on a class basis and capable of providing a focus for the development of proletarian consciousness. The Central Committee was connected to the Generalidad and disappeared with the passing of a simple decree when the new government of Catalonia was formed in October.

The Central Committee of the militias represented a superb weapon of capitalism for leading the workers out of their towns and localities to fight on the territorial fronts where they are being ruthlessly massacred. It is the organ that established order in Catalonia, not in conjunction with the workers, but against the workers who had been dispersed to the fronts. It is true that the regular army was practically dissolved, but it is gradually being reconstituted within the militia columns whose general staff – Sandino, Villalba and Co. – are clearly bourgeois. The columns are made up of volunteers and this will probably remain the case until the intoxication and illusion in the ‘revolution’ is over and capitalist reality is restored. Then we will soon see the official re-establishment of a regular army and obligatory service”.

The immediate participation of the CNT and the POUM (‘Marxist Party of Workers Unification’, situated somewhere between left social democracy and Trotskyism) in these bourgeois institutions was a blow against the possibility of the class organs created in streets and the factories during the July days centralising themselves and establishing an authentic dual power. On the contrary, the latter were quickly emptied of their proletarian content and incorporated into the new structures of bourgeois power.

Secondly, a burning political question of the day was not confronted and, lacking any analysis of the historic trends at work within capitalist society, the anarchists had no method for confronting: the nature of fascism and what Bordiga called its “worst product”, anti-fascism. If the rise of fascism was one expression of a series of historic defeats for the proletarian revolution, preparing bourgeois society for a second inter-imperialist massacre, anti-fascism was no less a rallying cry for imperialist war, no less a call for workers to give up the defence of their own class interests in the name of a sacred ‘national unity’. It was above all this ideology of anti-fascist unity which enabled the bourgeoisie to avert the danger of proletarian revolution by diverting the class war in the cities into a military conflict at the front. The call to sacrifice everything for the struggle to defeat Franco led even the most passionate advocates of libertarian communism, such as Durruti, to accept this grand manoeuvre. The militias, by being incorporated into an organ like the CCAM, dominated by parties and unions such as the Republican and nationalist left, the Socialists and the Stalinists, which were openly opposed to the proletarian revolution, became instruments in a war between two capitalist factions, a conflict which almost immediately turned into a global inter-imperialist battlefield, a rehearsal for the next world war. Their democratic forms - such as the election of officers – did not fundamentally alter this. It’s true that the leading forces of bourgeois order – the Stalinists and Republicans – were never comfortable with these forms and later insisted on them being fully subsumed into a traditional bourgeois army, as Bilan had predicted. But as Bilan also realised, the fatal blow had already been struck in the first weeks after the military coup.

It was the same with the most obvious example of the bankruptcy of the CNT – the decision of four of its best-known leaders, including the former radical Garcia Oliver, to become ministers in the central Madrid government, and to compound this act of treason with their infamous claim that thanks to their participation in the ministries, the Republican state “had ceased to be an oppressive force against the working class, just as the state no longer represents the organism which divide society into classes. And both will tend even less to oppress the people as a result of the intervention of the CNT”12. This was the final step in a trajectory that had been prepared a long time in advance by the slow degeneration of the CNT. In a series of articles on the history of the CNT, we showed that the CNT, despite its proletarian origins and the deeply held revolutionary convictions of many of its militants, was unable to resist a remorseless tendency in capitalism in its epoch of state totalitarianism – the tendency for all permanent mass workers’ organisations to be integrated into the state. This had already been shown long before the July events , such as during the elections of February 1936, when the CNT abandoned its traditional abstentionism in favour of tactically supporting a vote for the Republic13. And in the period immediately after Franco’s coup, when the central Republican government was in utter disarray, the process of anarchist participation in the bourgeois state accelerated at all levels. Thus well before the scandal of the four anarchist ministers, the CNT had already joined the regional government of Catalonia, the Generalidad, and at the local level – no doubt in line with its rather vague notion of ‘free municipalities’ – anarchist militants became representatives and officials of the organs of local government, i.e. the base units of the capitalist state. As with the betrayal of social democracy in 1914, this was not just a matter of a few bad leaders, but the product of a gradual process of the integration of an entire organisational apparatus into bourgeois society and its state. Certainly within the CNT-FAI, and in the wider anarchist movement inside and outside Spain, there were proletarian voices raised against this trajectory, although as we will see in the second part of this article, few managed to call into question the underlying theoretical roots of the betrayal.

Ah, but what about the collectivisations? Didn’t the most dedicated and courageous anarchists, like Durruti, insist that deepening the social revolution was the best way to defeat Franco? Wasn’t it above all the examples of self-managed factories and farms, the attempts to get rid of the wage form in numerous villages throughout Spain, which convinced many, even marxists like Grandizo Munis14, that the social revolution in Spain reached heights never attained in Russia, with its rapid descent into state capitalism?

But Bilan rejected any idealisation of the factory occupations:

“When the workers went back to work in the factories where the bosses had fled or had been shot by the masses, factory councils were set up as an expression of the expropriation of these companies by the workers.

Here the trade unions intervened very quickly, setting up a procedure that would allow proportional representation in places where the CNT and the UGT had members. Moreover, although the workers returned to work on condition that they would be getting a 36 hour week and a wage increase, the unions intervened to defend the need to work at full output for the war effort, without worrying too much about the regulation of work or about wages.

The factory committees and the committees for the control of industries which were not expropriated (out of consideration for foreign capital or for other reasons) were thus immediately smothered; transformed into organs for stimulating production, they lost their class content. They were not organs created during an insurrectionary strike in order to overthrow the state; they were organs whose function was the organization of the war, and this was an essential precondition for the survival and reinforcement of the state” (ibid).

Damier does not dwell too much on the conditions in the ‘worker-controlled’ factories. It is significant that he gives more space to examining the democratic forms of the village collectives, their deep concern for debate and self-education through regular assemblies and elected committees, their attempts to do away with the wages system. These were indeed heroic efforts but the conditions of rural isolation made it less urgent for the capitalist state to launch a direct assault – by guile or outright force – on the village collectives. In sum these changes in the countryside did not alter the general process of bourgeois recuperation which was focused on the cities and the factories, where work discipline for a state capitalist war economy was imposed in a more ruthless and rapid manner and could not have been imposed without the fiction of ‘union control’ via the CNT

“The most interesting fact here is this. Following the expropriation of companies in Catalonia, their co-ordination through the Council of the Economy in August, and the government decree of October laying down the norms for ‘collectivization’, after each one of these steps came new measures for disciplining the workers in the factories – discipline they would never have put up with under the old bosses. In October the CNT issued an order forbidding defensive struggle of any kind and stating that the workers’ most sacred duty was to increase production. Apart from the fact that we have already rejected the Soviet fraud, which consists of the physical assassination of the workers in the name of “building socialism”, we declare openly that for us the struggle in the factories cannot cease for a moment as long as the domination of the capitalist state continues. Certainly the workers will have to make sacrifices after the proletarian revolution, but a revolutionary will never advocate the cessation of defensive struggles as a way of achieving socialism. Even after the revolution we will not deprive the workers of the strike weapon, and it goes without saying that when the proletariat is not in power – as is the case in Spain – the militarization of the factories is the same as the militarization of the factories in any capitalist state at war” (Bilan, op cit).

Bilan here is basing itself on the axiom that social revolution and imperialist war are diametrically opposed tendencies in capitalist society. Defeat of the working class opens the way to imperialist war – ideological in 1914, physical and ideological in the 1930s. Class war on the other hand can only be waged at the expense of the war economy. Strikes and mutinies do not strengthen the national war effort. It was the revolutionary outbreaks of 1917 and 1918 which forced the warring imperialisms to bring their hostilities to an immediate end.

There is such a thing as revolutionary war. But it can only be waged once the working class is in power – on this Lenin and those who rallied to him in the Bolshevik party were very clear in the period February to October 1917. And even then, the demands of a revolutionary war fought on the territorial fronts do not create the best conditions for the flowering of class power and for a radical social transformation- far from it. Thus between 1917 and 1920 the Soviet state defeated the internal and external counter-revolutionary forces at the military level, but at a very high price: the erosion of political control by the working class and the autonomisation of the state apparatus.

This fundamental opposition between imperialist war and social revolution was doubly confirmed by the events of May 37.

Here again – this time faced with a provocation by the Stalinists and other state forces, who attempted to seize the Barcelona telephone exchange from the workers who controlled it – the Barcelona proletariat responded en masse and with its own methods of struggle: mass strike and barricades. The ‘revolutionary defeatism’ advocated by the Italian left, castigated as insane and traitorous by virtually every political tendency from the liberals to ‘left communist’ groups like Union Communiste – was put into practice by the workers of Barcelona. This was essentially a defensive reaction to an attack by the repressive forces of the Republican state, but it once again pitted the workers against the whole state machine, whose most brazen mouthpieces did not hesitate to denounce them as traitors, as saboteurs of the war effort. And implicitly, this was indeed a direct challenge to the anti-fascist war, no less than the Kiel mutiny of 1918 was a challenge to the war effort of German imperialism and, by extension, to the whole inter-imperialist conflict.

The open defenders of bourgeois order were to respond with brutal terror against the workers. Revolutionaries were arrested, tortured, shot. Camillo Berneri, the Italian anarchist who had openly expressed his criticisms of the CNT policy of collaboration, was among the many militants kidnapped and killed, in the majority of cases by the thugs of the ‘Communist’ party. But the repression really only descended on the workers once they had been persuaded to lay down their arms and go back to work by the spokespeople of the ‘left’ , of the CNT and the POUM, who were above all terrified of a fracture in the anti-fascist front. The CNT – like the SPD in the German revolution 1918 – was indispensable in the restoration of bourgeois order.

C D Ward

In the second part of this article we will look at some of the anarchist tendencies which denounced the betrayals of the CNT during the war in Spain, in particular the Friends of Durruti and Camillo Berneri. We shall try to show that while these were healthy proletarian reactions, they rarely called into question the underlying weaknesses of the anarchist ‘programme’.

1In our article in International Review 120, ‘Anarcho-syndicalism faces a change in epoch: the CGT up to 1914’ we pointed out that this orientation of certain anarchist currents towards the unions was based more on the search for a more receptive audience for their propaganda than a real understanding of the revolutionary nature of the working class.

4 See the article on the Great Depression in International Review 146

5 Black Cat Press, Edmonton, 2009. Originally published in Russian in 2000. Damier is a member of the KRAS, the Russian section of the IWA. The ICC has published a number of its internationalist statements on the wars in the former USSR.

6Federacion Obrera Regional Argentina

7‘Anarchism in Argentina and Uruguay’ in Anarchism Today, edited by David Apter and James Joll,Macmillan, 1971, p 185. Available online at https://www.libcom.org/files/Argentina.pdf

8This organisation – the SR stands for ‘Revolutionary Syndicalist’ – was the result of a split in 1926 with the ‘official’ CGT, which at the time was dominated mainly by the Socialist Party. It remained a rather small group and disappeared under the Petain regime during the Second World War. Its main spokesman at the Zaragoza Congress was Pierre Besnard.

10“At first sight this mode of thinking seems to us very luminous, because it is that of so-called sound common sense. Only sound common sense, respectable fellow that he is, in the homely realm of his own four walls, has very wonderful adventures directly he ventures out into the wide world of research. And the metaphysical mode of thought, justifiable and even necessary as it is in a number of domains whose extent varies according to the nature of the particular object of investigation, sooner or later reaches a limit, beyond which it becomes one-sided, restricted, abstract, lost in insoluble contradictions. In the contemplation of individual things it forgets the connection between them; in the contemplation of their existence, it forgets the beginning and end of that existence; of their repose, it forgets their motion. It cannot see the wood for the trees”. Anti-Dühring, Introduction

11Our article on the CGT cited in footnote 2 makes the same point about a book produced by two leading militants of the French anarcho-syndicalist organisation in 1909: “The book by Pouget and Pataud, which we have already quoted (Comment nous ferons la revolution), is very instructive in this respect, since the revolution that it describes is in fact purely national. The two anarcho-syndicalist authors did not wait for Stalin to envisage the construction of ‘anarchism in a single country’: once the revolution has been successful in France, a whole chapter of the book is devoted to describing the system of foreign trade, which is to continue commercial operations abroad while production is organised on communist principles within French borders”

12Quoted in Vernon Richards, Lessons of the Spanish Revolution, London, Freedom press1983 (first published in 1953) chapter VI, p 69

13See the series on the history of the CNT in IRs 129-133, in particular the last article, ‘Anti-fascism, the road to the betrayal of the CNT’.

14 Munis was a leading figure in the Bolshevik-Leninist group in Spain which was linked to Trotsky’s tendency. He later broke with Trotskyism over its support for the Second World War and evolved towards many of the positions of the communist left. We have published polemics with the group later founded by Munis, Fomento Obrera Revolucionario, on its view of the Spanish war.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us Digg

Digg Newskicks

Newskicks Ping This!

Ping This! Favorite on Technorati

Favorite on Technorati Blinklist

Blinklist Furl

Furl Mister Wong

Mister Wong Mixx

Mixx Newsvine

Newsvine StumbleUpon

StumbleUpon Viadeo

Viadeo Icerocket

Icerocket Yahoo

Yahoo identi.ca

identi.ca Google+

Google+ Reddit

Reddit SlashDot

SlashDot Twitter

Twitter Box

Box Diigo

Diigo Facebook

Facebook Google

Google LinkedIn

LinkedIn MySpace

MySpace