Submitted by International Review on

The bourgeoisie presents the Gulf War in a contradictory manner - they claim it is both the cause of the current recession, and the means of overcoming it, thanks to the setting up of a 'new world order' of prosperity and stability. These are just lies aimed at hiding the reality of a crisis which has been developing for more than 20 years and is accelerating dramatically today. The result of the war can only be an aggravation of the crisis, and all the world's workers will feel its effects

War is permanent in decadent capitalism

War is inseparable from the life of capital[1]. Since the Second World War, hardly a year has gone by without the clash of arms being heard. Usually, when the ruling class has been able to talk about a period of peace, this merely meant that the big imperialist powers weren't massively involved in a direct confrontation. And even this statement is relative: since the second world war we've seen, without any break in continuity, France in Indochina, the Korean War, the Suez affair, the war in Algeria, the Vietnam war, the Arab-Israeli wars, the Red Army in Afghanistan, the Iran-Iraq war, US troops in Lebanon and Panama, and today Kuwait - all of them conflicts in which the 'great powers' have been more or less directly involved. Right now we can count a dozen conflicts in Africa alone. The numerous wars which have taken place since 1945 have killed almost as many people as the Second World War.

The profoundly war-like nature of capital has more and more stamped itself on the whole of its economy. In the aftermath of the Second World War, while forbidding the defeated countries, Germany and Japan, from engaging in any significant program of rearmament, the victorious countries didn't relax their military efforts at all. On the contrary, with the new rivalry between 'East' and 'West', the whole world economy was subjected to the requirements of the arms race. And so the 'economic' mode of organization which made its appearance in the 1914-18 war - ie state capitalism, which puts the economy at the service of militarism - has been continuously developed and perfected over the past 50 years.

The situation of the two major imperialist powers during the 80s, the USA and the USSR, is particularly significant in this respect.

As the world's major economic power, the USA devoted, during this period, around 6 % of its annual GNP to the arms budget. Such a sum represents something like 7 or 8 times the annual GNP of the entire African continent and 3 and a half times that of Latin America. All key industries are dependent on the Pentagon's arms orders. Boeing, Macdonnell-Douglas, Texas Instruments, General Electric, Chrysler, etc, would go bust if they had to go without this manna from heaven.

The former superpower, the USSR, was only able to keep up with its' great rival by developing an increasingly preponderant part of its economy to the arms race. Although at the time he became president Gorbachev claimed that only 7% of the ousters GNP was devoted to the military budget, in 1989 his advisors declared that it was really closer to 30%. And it would be quite wrong to think that, during these years, the stalinist Nomenklatura were the only ones who were lying about arms expenditure.

By definition, military programs are subject to secrecy and are constantly minimized. What's true for the USSR is also true for others, though probably to a lesser degree. We have already noted that military orders subsidize key industries and orient research; at the same time, many civil 'research' and equipment programs are in fact used for military ends. For example, if France is today equipped with some of the most important 'civil' atomic reactor stations in the world, it's above all because this corresponds to its army's need for plutonium for its nuclear 'strike force'. The French are thus financing the army whenever they pay their electricity bills.

It's not only in the USSR that tractor factories are also used to produce armored cars, it's not only in Iraq or Libya that fertilizer plants produce chemical weapons. In the USA, 90% of research labs and centers are controlled and financed more or less directly by the Pentagon. Not only is the portion of production devoted to armaments of all kinds underestimated everywhere: above all, no figures can express the qualitative distortion imposed on the whole of economic life by the war economy - the location of centers of production in line with strategic-military considerations rather than economic ones; the orientation of civil research towards the needs of the army at the expense of other necessities. There's no lack of examples, from the first motorways built in Germany and Italy in the 30s, the aim of which was above all to allow tanks to go as quickly as possible from one end of the country to the other, to the first computer, the ENIAC, built in the USA for the Pentagon, whose nuclear experimentation centre at Los Alamos has since then always been equipped with the most advanced computers of the moment.

Arms production is a destruction of wealth

Today, armaments crystallize the nec plus ultra of technological perfection. The fabrication of sophisticated systems of destruction has become the symbol of a modem high-performance economy. However, these technological 'marvels', which have just shown their murderous efficiency in the Middle East, are, from the standpoint of production, of the economy, a gigantic waste.

Weapons, unlike most other commodities, have the particular feature that once produced they are ejected from the productive cycle of capital. They serve neither to enlarge or replace constant capital (unlike machines, for example) nor to renew the labor power of the workers who set this constant capital in motion. Not only do weapons do nothing but destroy - they are already a destruction of capital in themselves, a sterilization of wealth. When the USA, for example, announces that the defense budget represents 6 % of GNP, that means that 6% of the annually produced wealth has been destroyed. This 6% has to be withdrawn from overall production, which means that military production should be subtracted from annual growth, not added on as the economists do.

The sterilizing effect the war economy has on the productive apparatus can be illustrated perfectly by the economic evolution of the great powers these last few years. The example of the USSR is illuminating: far from dynamiting the economy, the sacrifice of the latter to the needs of the Red Army has led to the increasingly dramatic ruination of the productive apparatus. For its imperialist needs the USSR developed an advanced aerospace industry. But at the same time, due to lack of investment, agricultural production - to take one of many examples - stagnated to the point where the former granary of Europe now has to import cereals in order to avoid famine.

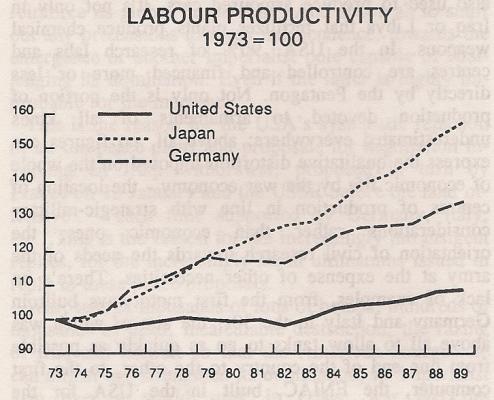

The Russian economy finally caved in under the weight of this monstrous war machine. What's true for the USSR is also true for the USA, even if it's obviously in a less spectacular manner. Here it's enough to note the USA's loss of competitiveness vis-à-vis its main economic rivals, Germany and Japan. The economies of these two, who were prevented from rearming at the end of World War II, have been much less punctured by the needs of the military. This isn't the only reason for the record productivity of these countries, but it is the main one.

In these conditions, why keep up an army if the final result is to weaken the whole productive apparatus?

The crisis pushes capital to 'escape forwards’ into war

From the strictly economic standpoint, this is indeed an aberration. However, production isn't everything. Of course, every national capital has to ensure that it has stable supplies of raw materials and outlets for the production of its industries, in order to realize the surplus value they contain, but these economic interests are mixed up with the global geo-strategies of imperialism, which plays a decisive role and imposes its own objectives.

Since the beginning of the century, when all the markets of the planet have been controlled by one or another of the great powers, the most poorly placed of all these powers have been forced to resort to war to save their economies, either to find new markets to exploit, or simply to pillage others in order to maintain the process of accumulation. This is what Germany attempted to do in 1914 and 1939, Japan in 1941, and the USSR after 1945. The more competition is exacerbated in a fundamentally saturated world market, the greater the tendency to 'escape forwards' into armaments programs, the strengthening of military power, ie of imperialism. Faced with an economic impasse, the solutions of militarism tend to impose their own logic, and this is not purely economic. While for the victorious country war can be a way of strengthening its position, of grabbing new riches, this isn't the case in general. To verify this we only have to look at the weakening of Britain and France after World War II, despite the fact that these were 'victorious' countries. And whatever happens, from the standpoint of global capital, ie that value accumulated on a world-wide scale, wealth has been destroyed irredeemably. This amply proves the irrationality of war from the economic point of view.

The present situation, characterized by an accelerated dive into open recession by the main industrial powers; by the collapse of entire segments of world capital, including the whole of the eastern bloc; by a Middle East war which has involved the biggest concentrations of forces of destruction since the Second World War all this shows what an apocalyptic spiral world capital is caught up in.

Crisis, chaos and war

The 'Gulf War' is, in the final analysis, the product of the economic crisis which has been shaking world capitalism since the end of the 60s[2]. The first consequence of the economic collapse of the USSR has been the break-up of its bloc and the destabilization of the entire world situation. The tendency for 'every man for himself, exacerbated by the crisis, has accelerated in the context of the gaping whole left by the disappearance of the discipline imposed by the blocs.

The countries of Eastern Europe have rushed to throw of the tutelage of Russia. As for the USA's vassals, now they no longer need American protection from the Russian danger, they are more and more asserting their strivings for independence, whereas many regional powers in the periphery of capitalism are being tempted to profit from the situation and improve their own position.

Iraq is an example of this: confronted with an astronomical debt, estimated at $70 billion (more than twice its annual GNP), and quite unable to repay it, it took advantage of its military power to get its hands on ultra-rich Kuwait. Such an example is a significant expression of the chaos which has developed internationally, and of which the break-up of the USSR itself is a striking aspect.

The USA's determination to deal with Iraq, to make an example of it, is above all the expression of the necessity to put an end to planetary chaos.

The analysis which sees the Gulf war as no more than a struggle for oil doesn't stand up to economic reality. Even if Iraq is at the centre of the world's main oil-producing zone, the fact is that the sources of oil have grown and diversified, and Middle East oil no longer plays the same central role that it did in the 70s. To see how much overproduction there is, you only have to note the fact that, after a brief speculative surge, oil prices are again falling despite the halt in production in Iraq and Kuwait. The danger of the moment is not a scarcity of oil.

Even if other factors have played a part in the US intervention - dismantling Iraq's military power, reinforcing the 'Pax Americana' in the Middle East and the USA's control over oil - they remain secondary compared to the essential aim of American capital; to face up to the growing chaos.

Because the interests of its national capital coincide with the defense of a 'world order' which is above all its order, the USA is particularly sensitive to the growing disorder of international relations. It is also the knell one which has the military means to play the role of world cop.

And it's with considerable disquiet that the USA's main economic competitors are now regarding America's current demonstration of its superiority after all, they had hoped to emancipate themselves from the USA's tutelage after the downfall of the eastern bloc. The illusion of a new bloc in Europe around Germany has been reduced to nothing, as can be seen from the cacophony of European foreign policies in the face of American demands. The economic powers of Europe and Japan know quite well that the USA will take advantage of its present position of strength in order to force more economic sacrifices from them at a time when the acceleration of the crisis is exacerbating the trade war.

The full force of the open recession

The first effect of the Gulf war has been to put concern about the economic crisis on the back-burner, to hide it. If you follow the bourgeois media there's an astounding contrast between the period before the outbreak of the war and the period that came after. The alarmism about a new stock market crash and a catastrophic rise in oil prices which prevailed before the war has proved to be unfounded up to now; and, all of a sudden, a new facade of optimism has been created. The propaganda does its best to minimize the seriousness of the crisis and to play down its dramatic effects. Thanks to the war, the recession - which had only just been officially recognized by the US government, was now given a ready-made 'explanation': Saddam's to blame, he's responsible for all the difficulties, and so, logically, these problems will disappear when the war's over. This is what Bush was implying when he declared that the American recession would bottom-out in the next year and that it was 'psychological' factors that were aggravating the situation! Alan Greenspan, chairman of the FED, declared that but for the Gulf crisis, the American economy "would perhaps have passed by the recession"and added that "the worst pan of the shock of the crisis has already been absorbed and the tendency towards a drop in activity will now be attenuated."

Reality is of course far away from these optimistic declarations. The American economy is plunging with increasing speed into the recession, and it didn't need the war for this to happen.

In November 1990, orders for durable goods in the USA fell by 10.1 % and the December lull of plus 4.4% is essentially due to a 57% rise in military orders. For 1990 as a whole, there was a 1.6% drop, the American economy's worst since 1982, a year of full recession.

Certain sectors, by no means secondary ones, are in deep trouble. For example, cars and air transport. In mid-December 1990, the fall in car sales reached a catastrophic level - 19%. General Motor's losses reached $2 billion in 1990; Ford, despite being the most competitive of American car-makers, lost $90 and $736 million in the last two quarters of 1990. The air companies' wings have been broken. TWA has been declared bankrupt, Eastern Airlines is being liquidated, Pan Am and Continental are in a very bad state. In all, the American air companies piled up $2 billion in losses in 1990, a historic record.

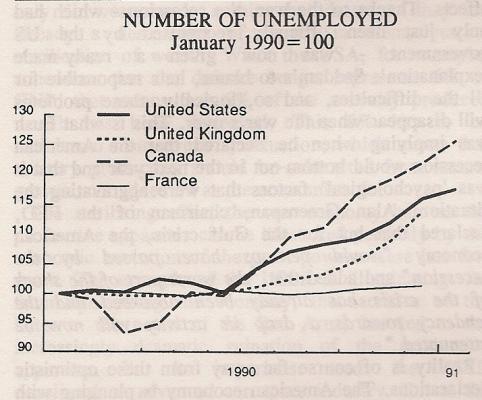

As a result, lay-offs are multiplying. Unemployment has been rising at record rates in the USA over the last half-year.

In the USA, in 1989, 2,500,000 jobs were created, but only 500,000 in 1990, and still this overall result for the year hides the catastrophic reality of the second six months, during which 900,000 jobs were wiped out.

The result: the American banks, already shaken by the collapse of property and stock-exchange speculation, have seen a huge growth in defaults.

During the last quarter of 1990, 11.6% of the banks registered losses pure and simple, and the majority have only been able to maintain a positive balance sheet by selling assets which in fact represents a weakening. In 1990, 169 banks went bust, total assets of $16 billion. In 1991, 180 banks are expected to fail, and that would mean total assets of $70 billion.

To this must be added the failure of more than 500 'Savings and Loans' enterprises since 1988, leaving the state with a bill which is estimated at between $500 and $100 billion!

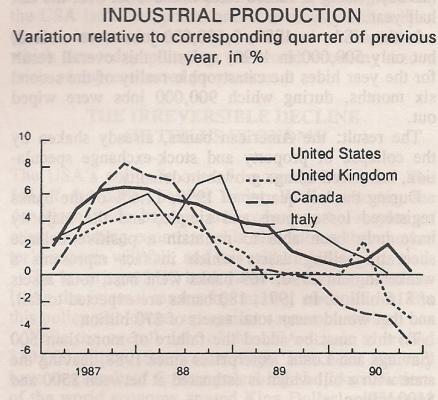

When the world's first economy is in crisis like this, the world economy is bound to be hit on the rebound. Within the OECD, Britain, Canada, Australia and New Zealand have entered into open recession. Industrial production in France and Italy is down. Everywhere growth is falling.

In Europe, car sales have fallen by 3.7% in one year: 5% in Italy, 8% in France, 18% in GB. Sales of heavy goods vehicles have fallen by 5%. Fiat's profits have shot down 55 %. Symbolically, Rolls Royce has decided to drop production of its prestigious cars, and Saab has buried the Swedish 'model' by closing a brand new plant in Malmo (opened in 1989).

Like their American competitors, the European air companies are deep in crisis. For the first time since 1981, their overall results in 1990 were negative. Air France, Lufthanser, British Airways and Swissair have dropped the least-profitable lines. Air France has asked for a report on the delivery of the new Airbus, which has already been ordered. British Airways has announced 4,900 job cuts and the Scandinavian company SASenvisages getting rid of 3,500 workers.

In the heart of the industrialized world, competition is exacerbating and is taking on the dimensions of a bitter trade war.

For example: there's full-scale war over air fares. On 11 February, British Airways announced a 33% reduction in its London to New York fare, and in the next few hours, TW A and Pan Am followed suit. These companies, though in a very poor financial state, are still forced to eat into their profit margins to protect their markets and nab a few customers. The only result of such practices will be to accelerate the deterioration of the overall balance sheet in this sector. And what's true for air transport is true elsewhere. In all sectors numerous enterprises have gone into the red, and in the interests of survival, anything is permitted.

'Everyman for himself': Frenzied economic competition

Economic competition isn't limited to a price war. Each state, concerned about the defense of its national economy, uses whatever resources it has to buttress its power. Rivalries tend to shift from a strictly economic level to a terrain which doesn't have much to do with the rules of ‘free competition’.

For decades, the leader of the western bloc, the USA, imposed on its vassals a way of controlling the world economy which has above all profitable to itself, and this at the price of a huge attempt to cheat the law of value. The intransigent advocates of the 'laws of the market' 'free competition' and 'liberal capitalism' are the very ones who have done most to distort these rules in defense of the interests of the national capital. The most recent events on the international scene are flagrant proof of this.

At the end of 1990, the GAIT talks which have been going on for years became highly venomous. Furious about European resistance on the question of agricultural and industrial subsidies, the USA simply adjourned these meetings.

The USA's demonstration of force in the Gulf has shown quite clearly that Europe doesn't have the means to back up its ambitions, on the economic as well as on the military level.

It's enough to note the media's change of tone about Germany and Japan. These two, which hitherto have been presented as the examples of strong and solid economies as new giants challenging a declining America, are now in the dock accused of economic egoism. They may be economic giants, but Germany and Japan are still political and military dwarfs. Faced with the American imperialist superpower they are for the moment obliged to admit their weakness. Despite all their efforts to resist on the economic level, they can only yield ground at present.

Since the beginning of the Gulf war, many of those who, a few weeks ago were making a show of resistance, have now fallen in line. The European Commission now proposes a reduction of subsidies for the new Airbus program. These were precisely the points which for months were the nub of the disagreement in the GAIT talks between the EEC and the USA. Faced with the evidence of military fact, the EEC has thus swallowed its pride and yielded without further discussions to the USA's demands - and these concessions will still probably be insufficient in the USA's eyes.

As for Japan and Germany, they have finally acceded to Washington's pressure to help finance 'Operation Desert Storm', agreeing to contribute $13 billion and $7.7 billion respectively, a significant little hand-out.

Because they are the strongest, the Americans can impose their law on the world market. This is particularly illustrated by the role of the dollar. The value of the dollar doesn't at all correspond to economic reality. It is above all the expression of US domination of the world market, and is an essential instrument of this domination. The first aim of the organized fall of the dollar above all was to restore artificially the competitiveness of American products at the expense of European and Japanese competitors. Its result has been to reduce the US trade deficit and consequently to reduce other countries' trade surplus.

The fall in bank rates has had the result of making credit less expensive, thus holding back the fall in production by facilitating consumption and investment.

That Germany and Japan still appear to be prosperous is highly provisional. For years these countries were the exceptions which made it possible to perpetuate the myth that sound capitalist management was the way to overcome the crisis. Not only are these countries now in the firing line of the USA's efforts to safeguard its own capital, they are also, and above all, beginning to be shaken in their turn by the effects of the crisis.

The fall in the dollar is beginning to hit their exports which are falling more rapidly than the US trade deficit is being redressed. In November '90 alone, the German trade surplus fell by 60%. With the dollar reaching its lowest-ever level against the Yen and the Mark, the export enterprises of these countries are making disastrous losses. In Germany, for example, Deutsche Airbus lost half its capital for this reason.

The record growth rates for German production, 4.6% in 1990, have to be relativized for two reasons.

First, it doesn't take into account the 50% fall in production in the ex-GDR.

Secondly, it is not the result of a growth in exports, which have largely fallen, but of state borrowing aimed at subsidizing the reconstruction of East Germany. As an indication of the poor health of the German economy, unemployment is again growing in the west, while in the east official unemployment is 800,000, but in fact 1,800,000 are partially unemployed and a million redundancies have been announced for the period ahead!

Japan has also seen its exports falling rapidly. But the economic crisis is above all taking the form of an unprecedented financial crisis. Japan has been the centre of international speculation and today, more than any other country, it's paying the price.

The Tokyo stock exchange fell further than any other in 1990 - 39% - and Japanese banks are today threatened on the one hand by the collapse of property speculation, and on the other by the non-reimbursement of the astronomical credits they have agreed to all over the world. Thus the Far Eastern Review estimates that between 1985 and 1990, half of all private international credit had been granted by Japanese banks.

These credits were mainly given in dollars, and since the dollar has fallen in value daily, this means that, apart from the fact that with the growing recession a good portion of these credits won't be paid back, those which are will still only represent a small part of the value they had when the dollar was worth more. Indeed, the biggest debt of all, the USA's, has been devalued by 50% in relation to the Yen. Financial catastrophe is predictable and inevitable in such circumstances, and will still have a weight on the Japanese economy.

The Japanese and German economies have had their good times. The future for them, as for all other parts of world capital, is going to be grim.

While it's far and away the world's leading power, the USA isn't omnipotent and is obviously still subject to the insurmountable contradictions of capitalism, which are today plunging the world economy into a crisis of unprecedented proportions.

The irreversible decline of the US economy

The USA's policy is one of 'escaping forwards.' The fall of the dollar has its limits. While restoring the American trade balance and reducing the surplus of other exporting countries, this also means that the latter's imports will fall, and this will hit US exports.

The lowering of US bank rates has the aim of stimulating the internal market by making credit easier. But this policy also comes up against economic reality.

While the overall debt of the USA stands at around $10,000 billion, the present flight into debt can only have the result of further polarizing the contradictions of the world economy around King Dollar, making the arrival of the monetary crisis inevitable. To verify this you only have to look at the present attitude of the American banks, who despite all the pressure from the federal state, are reluctant to open the sluice-gates of credit, because they're already faced with the reality of masses of unpaid debts.

The American bourgeoisie no longer has confidence in the solvency of its economy.

With the arrival of the recession, the future US budget deficit is estimated at $350 billion, a historic record - without counting the cost of the war which will be tens of billions of dollars for the US alone.

The first result of the war will thus be to further aggravate the effects of the world crisis by worsening the budget deficits of the participating countries.

The gigantic destruction wrought in Iraq and Kuwait is cynically presented by the media as a source of new markets thanks to the prospect of reconstruction. If this really does take place, these glorious new markets will be completely insufficient to absorb the surplus production which is causing the cave-in of the world economy. Reconstructing Iraq's and Kuwait's oil-producing capacities will simply aggravate the overproduction of oil.

The respite that the US has tried to grab through its demonstration of force will be very short, if it happens at all. In any case, it won't allow it to come out of the recession which has in reality been there in concealed form since the beginning of the 80s, and which didn't need to wait for official recognition at the end of 1990 to make its effects felt. On the contrary, the recession is going to get worse.

The only real question isn't the existence of the crisis, but the speed and depth of its development.

For all parts of world capital, the problem is no longer pretending that they can overcome it, but limiting the damage to their own capital and trying to push the most pernicious effects onto others.

This is what has already happened. Since the beginning of the crisis at the end of the 1960s, the strongest countries have done all they can to deflect onto the weakest countries the most brutal effects of the generalized crisis of overproduction, which has its origins in the big centers of capitalist production. The dramatic situation of Africa, ravaged by wars, epidemics and famines; of South America which is heading in the same direction, where in 1990, wealth per inhabitant officially fell by 6% and where there is a continent-wide epidemic of cholera; the situation of the former COMECON countries where last year overall production fell by 30% - all this testifies to the growing collapse of the world economy, which is now threatening the great industrial centers in the developed countries.

••••

How remote seem the beautiful words of Bush, just after the collapse of the Russian bloc, only a few months ago. The promised world of peace and prosperity was just another lie. The trade war now hotting up will soon put paid to "beautiful" ideas about free trade, the end of European borders, growth and security. The workers of the world are going to feel the full force of capital's reality: war, misery, unemployment, famine, epidemics ...

The irrationality of war, which can only serve to aggravate the economic crisis, brutally expresses the catastrophic scale of the impasse of capitalism.

JJ

del.icio.us

del.icio.us Digg

Digg Newskicks

Newskicks Ping This!

Ping This! Favorite on Technorati

Favorite on Technorati Blinklist

Blinklist Furl

Furl Mister Wong

Mister Wong Mixx

Mixx Newsvine

Newsvine StumbleUpon

StumbleUpon Viadeo

Viadeo Icerocket

Icerocket Yahoo

Yahoo identi.ca

identi.ca Google+

Google+ Reddit

Reddit SlashDot

SlashDot Twitter

Twitter Box

Box Diigo

Diigo Facebook

Facebook Google

Google LinkedIn

LinkedIn MySpace

MySpace