Submitted by International Review on

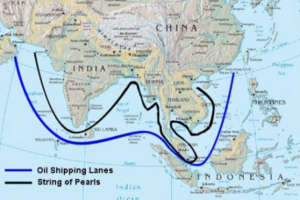

In addition to the long-standing close links with the regimes in Pakistan and Burma, China has been following a “string of pearls” strategy of setting up bases and building diplomatic ties. Some examples:

-

Signature of a military agreement with Cambodia.

-

Funding the construction of a canal across the Kra Isthmus in Thailand. The canal is planned to be 102 kilometres long and 500 metres wide and is to link the Indian Ocean to China’s Pacific coast – a project on the scale of the Panama Canal. It could tip Asia’s balance of power in China’s favour by giving China’s fleet and merchant navy easy access to a vast oceanic continuum stretching all the way from East Africa to Japan and the Korean Peninsula. This proposed canal would challenge Singapore’s position as the main regional port and help Chinese vessels to avoid the straits of Malacca. This has great strategic significance for the naval balance of power, and challenges India’s present dominant position in the Bay of Bengal1.

-

Construction of strategic infrastructure in Tibet and Myanmar.

-

Developing a port facility in Sittwe, Myanmar.

-

Electronic intelligence gathering facilities on islands in the Bay of Bengal.

-

Assistance to Bangladesh in developing its deep-sea port in Chittagong, sales of missile boats to Bangladesh.

-

Extensive military aid to Sri Lanka. China helped Sri Lanka to win the war against the Tamil Tigers in 2009, it also invested in the development of ports in Hambantota.

-

Building a naval base at Marao in the Maldives.

-

Setting up its first military base abroad in Seychelles.

-

Developing the Gwadar port on the south-west coast of Pakistan. China’s involvement in the construction of the deep-sea port of Gwadar has attracted much attention given its strategic location, about 70 kilometres from the Iranian border and 400 kilometres east of the Strait of Hormuz - the world's major oil supply route. It has been suggested that it will provide China with a “listening post” from where it can monitor US naval activity in the Persian Gulf and Indian activity in the Arabian Sea.

-

An anti-piracy mission in the Gulf of Aden.

The construction of such a “string of pearls” would allow China to threaten shipping at the three crucial bottlenecks in the Indian Ocean – Bab el Mandeb (connecting the Red Sea to the Gulf of Aden), the Strait of Hormuz, and the Strait of Malacca. Chinese naval officers speak of developing in the long-term three ocean-going fleets to patrol the seas around Japan and Korea, the Western Pacific, the Strait of Malacca and the Indian Ocean.

The construction of such a “string of pearls” would allow China to threaten shipping at the three crucial bottlenecks in the Indian Ocean – Bab el Mandeb (connecting the Red Sea to the Gulf of Aden), the Strait of Hormuz, and the Strait of Malacca. Chinese naval officers speak of developing in the long-term three ocean-going fleets to patrol the seas around Japan and Korea, the Western Pacific, the Strait of Malacca and the Indian Ocean.

As an emerging power, China claims more weight and influence, but this can only be at the expense of other countries, in particular at the expense of the USA. This polarises the whole regional situation. Countries are drawn towards China, or into the arms of the USA, whether they like it or not.

The Chinese ruling class want to make us believe that Beijing’s rise is meant to be a peaceful one, and that China has no expansionist intentions, that it will be a different kind of great power. The reality of the past 20 years shows that China's rise is inseparable from increased imperial and military ambitions. While it is unthinkable that China could today defeat the USA or set up a new Chinese-led bloc, the main impact of China’s rise has been to undermine US superiority: its ambitions have triggered a new arms race. In addition, its increased weight world wide has encouraged the weakened former bloc leader, Russia, to act side-by-side with China in many conflicts with the USA (e.g. Syria, Iran) and to support (overtly or covertly) all those regimes which are denounced by the USA as “rogue states" (North Korea, Iran) or which are “failed states” such as Pakistan. Although Russia is also not interested in seeing China becoming too strong, and while Moscow has no intention of becoming a servant of China, Russia has realised that acting together with China against the USA offers it greater new room for manoeuvre. This explains Russia's naval exercises with China in the Yellow Sea.

The arms race between China and its rivals

Since 1989, the Chinese military budget has risen by an average of 12.9 percent per year: according to GlobalSecurity.org, it is now the second-largest on the planet. The overall US budget for national security – not counting the various wars Washington is embroiled in – is running at over $800 billion, although some estimates place it above $1 trillion. Global research group IHS has forecast Beijing's military outlay to double from its 2011 US$119.8 billion, to US$238.2 billion by 2015. That exceeds the amount spent by the region's 12 key defense markets, including Japan and India. In 2011 Chinese military spending was 80% higher than that of Japan, and 200% higher than those of India. China's military budget in 2011 was 2.5 times bigger than the 2001 figure and has doubled every five years. China's military budget takes up 30% of the Asian total, although according to Western defense officials those totals do not include arms imports. Thus in reality the overall military budget is much higher. If the forecast is accurate, China’s military spending will overtake the combined military spending of NATO’s top eight members, bar the US. And while in the year 2000 the US military budget was still 20 times higher than the Chinese, in 2011/2012 the relation is 7:1.2

China's modernisation efforts have been directed mainly at developing longer range missiles and increasing its cyber-war capabilities. Its navy is now believed to be the third largest in the world behind only the US and Russia. The PLA's infantry contingent has been reduced, while the navy, air force and the Second Artillery Corps – responsible for China’s nuclear missiles – have all been increased.

While Chinese growth rates have often reached double figures, its military budget has grown even faster. To be sure, the Chinese army started from a weak position of, since the majority of its forces were land forces, poorly equipped and mainly seen as cannon fodder for big land battles. The Chinese military has little fighting experience. Their troops have not seen action since 1979 when they were given a drubbing by Vietnam. In contrast US troops have been fighting, modernising, and adapting their weaponry and tactics constantly, developing anti-satellite weapons, anti-ship missiles, cruise missiles, and cyber-warfare capabilities. The PLA's ability to undertake complex joint operations in a hostile environment is untested. China’s missile and submarine forces could pose a threat to American carrier groups near its coast, but it will be some time until they can do so further afield. Learning to use all these newly acquired weapons in battle il likely to take years. Nevertheless, these ambitious armaments projects and China's expansionist strategy mean that the USA now perceives it among "major and emerging powers” as the country with “greatest potential to compete militarily” with the United States. Although even according to the Pentagon the Chinese military is "still decades away from possessing a comprehensive capability to engage and defeat a modern adversary beyond China's boundaries", leaders in the USA warn that “China's military is growing and modernizing." "We must be vigilant. We must be strong. We must be prepared to confront any challenge. But the key to that region is going to be to develop a new era of defense cooperation between our countries, one in which our military shares security burdens in order to advance peace." (the 2012 US defence secretary Panetta3).

As a consequence of the construction of the “string of pearls” and the growing Chinese presence in the Pacific, its neighbours have been compelled to adapt their military planning. Some examples:

Japan has switched from having its weapons targeted principally at the Soviet Union to focus more on China. Despite the effects of the economic crisis Japan plans to spend $284 billion between 2011 and 2015 – including the deployment of more US Patriot missiles; the navy is to receive more blue-water ships. Japan and China are currently engaged in a dispute over a group of rocky islets lying on the edge of the continental shelf about 100 miles north-east of Taiwan (in Japanese Senkaku-island, Diaoyu Islands in Chinese). 4

In 2006, South Korea launched a 15-year military-modernization program projected to cost some $550 billion, with about one-third slated for arms purchases. In 2012 it tested cruise missiles with a range of 930 miles, able to reach any location in North Korea. In view of the latest clashes with North Korea more money is to be made available for additional weapons.5

Australia is increasing its armaments budget, and has agreed to the deployment of an additional 2500 US soldiers and the construction of a new US base in the country.

2 Sources:

defensetech.org/2011/05/19/pla-chinese-military-doesnt-compare-to-u-s-military

csis.org/press/csis-in./panetta-outlines-us-military-strategy-asia

https://www.globalsecurity.org/military/world/china/budget.htm

Shen Dingli in Le Monde Diplomatique, May 2012

4 factsanddetails.com/japan.php?itemid=819&catid=22&subcatid=148

del.icio.us

del.icio.us Digg

Digg Newskicks

Newskicks Ping This!

Ping This! Favorite on Technorati

Favorite on Technorati Blinklist

Blinklist Furl

Furl Mister Wong

Mister Wong Mixx

Mixx Newsvine

Newsvine StumbleUpon

StumbleUpon Viadeo

Viadeo Icerocket

Icerocket Yahoo

Yahoo identi.ca

identi.ca Google+

Google+ Reddit

Reddit SlashDot

SlashDot Twitter

Twitter Box

Box Diigo

Diigo Facebook

Facebook Google

Google LinkedIn

LinkedIn MySpace

MySpace