ICConline - 2007

- 6364 reads

ICConline, January 2007

- 3849 reads

“International Conference of revolutionary Marxism” in Korea

- 3492 reads

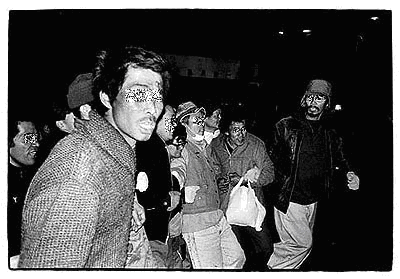

In October 2006, the Korean group "Socialist Political Alliance" called a conference in the towns of Seoul and Ulsan under the title "International Conference of revolutionary Marxism" , with the explicit purpose of reinforcing the presence of Left Communist positions within the Korean working class and its political minorities.

The conference in Korea was the first of its kind in the history of the workers' movement of that country and indeed in the whole of East Asia. That such a conference should be called today, in a country still divided by the consequences of the imperialist war launched more than 50 years ago, is an event of the greatest importance. It opens a perspective for the development of the international unity of the workers' movement between East and West for the first time since the brief experience of the Third International. However modestly, it heralds the appearance on the historical stage of the proletariat of the East.

Recognising this, the ICC did its utmost to contribute to the conference, presenting texts and taking an active part in the discussions. We are publishing below several documents, including the ICC's presentations on the subjects under debate, the declaration (presented jointly by the ICC and SPA) against the threat of war posed by the explosion of a North Korean nuclear test, and the ICC's report on the conference and the discussions that took place there. This latter has been discussed in the SPA, and the comrades have expressed their overall agreement with it.

There is nothing specifically Korean, nor even Asian, about the subjects under debate: the decadence of capitalism, the perspectives for the class struggle and for revolutionary organisation. The documents we are publishing below are part of an international debate in a new, emerging revolutionary movement. In this sense, we submit them for comment and discussion to comrades around the world.

Life of the ICC:

Geographical:

Heritage of the Communist Left:

General and theoretical questions:

Recent and ongoing:

Report on the conference in Korea, October 2006

- 5171 reads

In June 2006, the ICC received an invitation from the Socialist Political Alliance, a group based in South Korea which identifies itself with the tradition of the Communist Left, to take part in an "International Conference of Revolutionary Marxists", to be held in the towns of Seoul and Ulsan during October of the same year. We had been in contact with the SPA for about a year, and despite the inevitable difficulties of language had been able to begin discussions in particular on the questions of the decadence of capitalism and the perspectives for the development of communist organisations in the present period.

The spirit in which this Conference was called stands out powerfully in the SPA's introductory statement: "We know very well the various conferences or meetings of Marxists which are held regularly in various places in the world. But we also know very well the fact that those conferences are focusing on discussions about abstract theory in academia and the ritual solidarity between so-called "left" of capitalism. Beyond that, we recognise profoundly the vision that there is a need for true proletarian revolution against barbarism and war in the decadence phase of capitalism.

Although Korean workers express their difficulties on the shop floor and the revolutionary political forces in Korea are in the midst of confusion for the perspectives of future communist society, we have to accomplish the solidarity of world proletariat beyond one factory, one country and one nation, reflecting the desperate defeats neglecting the principles of internationalism in the past revolutionary movement from the bottom."

Even the briefest consideration of the history of the Far East is enough to reveal the immense importance of this initiative. As we said in our salute to the conference: "In 1927, the massacre of the workers of Shanghai was the final episode in a revolutionary struggle that had shaken the world for ten years, since the October Revolution in Russia in 1917. In the years that followed, the world working class, and humanity as a whole, suffered all the horror of the most terrible counter-revolution history has ever seen. In the East, the working population had to suffer the preface to World War II with the Japanese invasion of Manchuria, then the Second World War that culminated in the destruction of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, then civil war in China, the Korean War, the terrible famine in China during the so-called "Great Leap Forward" under Mao Zedong, the war in Vietnam...

All these fearful, earth-shaking events swept over a proletariat which, in the East, was still young and inexperienced, and which had very little contact with the development of communist theory in the West. As far as we know, no expressions of the communist left were able to survive or even appear among the workers of the East.

Consequently, the fact that today a conference of communist internationalists has been called in the East, by an organisation which explicitly identifies with the communist left, is an event of historic importance for the working class. It holds the promise - perhaps for the first time in history - of building a real unity between the workers of East and West. Nor is it an isolated event: on the contrary, it is a part of a slow world wide awakening to consciousness of the proletariat and its political minorities". The ICC's delegation thus attended the conference with the aim not only of helping to the best of our ability in the emergence of an internationalist, left communist voice in the Far East, but also to learn: what are the most important issues for the workers and revolutionaries in Korea? How are the questions that affect all workers posed there? What lessons can the experience of workers in Korea offer workers elsewhere, especially in the Far East but also more generally world wide? And what lessons can the Korean proletariat draw from the experience of its class brothers in the rest of the world?

The conference was originally intended to discuss the following subjects: the decadence of capitalism, the situation of the class struggle, and the strategy to be adopted by revolutionaries in the present situation. In the days leading up to the Conference, however, the long-term political importance of its goals was overshadowed by the dramatic sharpening of inter-imperialist tensions in the region caused by the explosion of North Korea's first nuclear bomb, and the manoeuverings that have followed it especially on the part of the different powers present in the region (USA, China, Japan, Russia, South Korea). In a meeting prior to the conference, the ICC delegation and the SPA's Seoul group agreed that it was of the first importance for the internationalists to take position publicly on this situation, and decided to present jointly to the conference an internationalist declaration against the threat of war. As we will see, the discussion provoked by this proposed declaration formed an important part of the debates during the conference itself.

In this Report, we propose to consider some of the main themes of the conference's debates, in the hope not only of giving a wider expression to the discussion itself, but also of contributing to the reflection of comrades in Korea by offering an international perspective on the questions that they are confronting today.

The historical context

Before we come to the conference itself, however, it is necessary briefly to place the situation in Korea within its historical context.

In the centuries preceding capitalism's expansion into the Far East, Korea both benefited and suffered from its geographical position as a small country caught between two great historical powers: China and Japan. On the one hand, it has served as a bridge and cultural catalyst for both countries: there is no doubt, for example, that ceramic art in China and especially Japan is greatly indebted to the artisan potters of Korea who developed the now lost techniques of celadon glazing.[1] On the other hand, the country suffered frequent and brutal invasions by its two powerful neighbours, and for much of its recent history the ruling ideology was dominated by a Confucian scholar caste which worked in Chinese and resisted the influx of new ideas that accompanied the arrival of European powers in the region. During the 19th century, the increasingly bitter rivalry between China, Japan, and Russia - the latter's colonial power now extended to the frontiers of China and the Pacific Ocean - led to an intense competition for influence within Korea itself. The influence sought by these powers, however, was essentially strategic: from the point of view of return on investment, the possibilities offered by China and Japan were far greater than those available in Korea, especially given the political instability caused by the internecine struggles between different factions of the Korean ruling classes, who were divided both as to the benefits of "modernisation", and by their efforts to use the influence of Korea's imperialist neighbours to bolster their own positions in power. The beginning of the 20th century saw an intensification of Russia's attempts to establish a naval base in Korea, which in turn could only be seen as a mortal threat to Japanese independence: this rivalry was to lead in 1905 to the outbreak of the Russo-Japanese war, during which the Japanese annihilated the Russian fleet. In 1910, the Japanese invaded Korea and established a colonial regime which was to last until Japan's defeat in 1945.

Industrial development prior to the Japanese invasion was thus extremely hesitant, and the industrialisation that followed was largely geared to the needs of the Japanese war economy: by 1945 there were some two million industrial workers in Korea, largely concentrated in the north. The south of the country remained essentially rural and suffered severe poverty. And as if the working population of Korea had not suffered enough from colonial domination, forced industrialisation, and war,[2] they now found themselves in the border zone of the new imperialist conflict that was to dominate the world until 1989: the division of the planet between the two great imperialist blocs of the USA and the USSR. The decision by the USSR to support the insurrection launched by the Stalinist "Korean Workers' Party" was in effect an attempt to probe the new frontiers of US imperial domination, in the same way as it did in Greece after 1945. The result was also the same, though on a far larger, more destructive scale: a vicious civil war between North and South Korea, in which the Korean authorities on both sides - however much they were fighting to defend their own bourgeois interests - were nothing more than pawns of far greater powers struggling for world domination. The war lasted for three years (1950-53), during which the whole peninsula was ravaged from one end to the other by the successive advances and retreats of the competing armies, and ended with its permanent division into two separate countries: North and South Korea. The United States has maintained a military presence in South Korea to this day, with over 30,000 troops currently stationed in the country.

Even before the end of the war, the USA had already come to the conclusion that military occupation in itself would not stabilise the region[3] and decided to enact what amounted to a Marshall Plan for South-East Asia and the Far East. "Aware that economic and social poverty was one of the main arguments used by the pro-Soviet nationalist factions who came to power in certain Asian countries, the USA created zones on the very borders of China (Taiwan, Hong Kong, South Korea and Japan) which could serve as outposts of western prosperity. The priority for the USA was to establish a cordon sanitaire against the advances of the Soviet bloc in Asia".[4] This policy had important implications for South Korea: "Lacking in raw materials, and with most of its industrial base limited to the north, the country was drained dry at the end of the war: production had fallen by 44% and employment by 59%. Sources of fresh capital, intermediate means of production, technical competence and managerial capacities were virtually non-existent (...) From 1945 to 1978, South Korea received some $13 billion, or $600 per inhabitant, and Taiwan $5.6 billion, or $4.5 per inhabitant. Between 1953 and 1960, foreign aid contributed almost 90% of fixed capital in South Korea. The aid given by the USA reached 14% of GNP in 1957 (...) But the USA did not restrict itself to supplying military, financial and technical aid to these countries; it also took charge of the whole management of the state and the economy. In the absence of real national bourgeoisies, the only social body capable of carrying out the modernisation that the USA wanted was the army. A highly effective form of state capitalism was installed in each of these countries. Economic growth was spurred on by a system which closely linked the public and private sectors through a quasi-military centralisation, but with the sanction of the market. In contrast to the east European version of state capitalism with its absurd bureaucratic excesses, these countries allied state centralisation with the sanction of the law of value. Numerous interventionist policies were carried out: the formation of industrial conglomerates, laws protecting the internal market, trade restrictions at the frontiers, a form of planning that was imperative but also incited further efforts, state management of the distribution of credit, the orientation of capital and resources towards the key sectors, the handing out of exclusive licenses, management monopolies etc. Thus in South Korea, it was thanks to a unique relationship with the chaebols (equivalent to the Japanese zaibatsus), great industrial conglomerates often founded through state aid or initiative,[5] that the public authorities oriented economic development".

The South Korean working class was thus faced with a policy of ferocious exploitation and forced industrialisation, carried out by an unstable succession of semi-democratic and authoritarian military regimes which maintained their power through the brutal suppression of workers' strikes and revolts, notably the mass uprising in Kwangju at the beginning of the 1980s.[6] Following the events in Kwangju, the Korean ruling class tried to stabilise the situation under the presidency of General Chun Doo-hwan (previously head of the Korean CIA) by giving a democratic veneer to what remained an essentially military authoritarian regime. The attempt failed miserably: the year 1986 saw mass opposition rallies in Seoul, Inch'on, Kwangju, Taegu and Pusan, while in 1987 "More than 3,300 industrial disputes erupted involving workers' demands for higher wages, better treatment, and better working conditions, forcing the government to make concessions to meet some of their demands".[7] The inability of General Chun's corrupt military regime to impose social peace by force led to a change of direction. The Chun regime adopted the "democratisation programme" proposed by General Roh Tae-woo, leader of the governmental Democratic Justice Party, who won the presidential elections held in December 1987. The presidential elections of 1992 brought to power a long-standing leader of the democratic opposition, Kim Young-Sam, and Korea's democratic transition was complete. Or, as the SPA comrades put it to us, the Korean bourgeoisie managed at last to erect a convincing democratic façade to hide the continued power of the alliance between the military, the chaebols, and the security apparatus.

Consequences of the historical context

In terms of the recent experience of its political minorities this historical context has parallels in other countries of the periphery, in Asia but also in Latin America.[8] It has had important consequences for the emergence of an internationalist movement in Korea itself.

At the level of what we might call the "collective memories" of the class, there is clearly an important difference between the accumulated political and organisational experience of the working class in Europe, which was already beginning to assert itself as an independent force in society in 1848 (the "physical force" fraction of the Chartist movement in Britain), and that of the class in Korea. If we remember that the waves of class struggle in Europe during the 1980s saw the slow development of a general distrust for the unions and a tendency for workers to take their struggles into their own hands, it is particularly striking that the movements in Korea during the same period were marked by a tendency to merge the workers' struggles for their own class demands with the demands of the "democracy movement" for a reorganisation of the bourgeois state apparatus. As a result, the fundamental opposition between the interests of the working class and the interests of the democratic fractions of the bourgeoisie were not immediately obvious to the militants who entered political activity in this period.

Nor should we underestimate the difficulties created by the language barrier. The "collective memory" of the working class is strongest when it takes a written, theoretical form. Whereas the political minorities that emerged in Europe during the 1970s had access to the writings, either in the original or in translation, of the left of the social democracy (Lenin, Luxemburg), then of the left of the Third International and the Communist Left that emerged from it (Bordiga, Pannekoek, Gorter, the Bilan group, and the French Communist Left), in Korean the work of Pannekoek (Workers' Councils) and Luxemburg (Accumulation of capital) is only just beginning to appear thanks to the joint efforts of the Seoul Group for Workers' Councils and SPA, with which the SGWC is closely associated.[9]

More specific to the Korean situation, has been the effect of the division between North and South imposed by the imperialist conflict between the US and Russian blocs, the US military presence in South Korea, and US support for the succession of military regimes which came to an end in 1988. Combined with the general inexperience of the working class in Korea and the absence within it of a clear internationalist voice, plus the confusion between the workers' movement and the bourgeois democratic opposition which we have described above, this has led to a general infection of society with a pervasive Korean nationalism, often disguised as an "anti-imperialism" in which only the United States and its allies appear as imperialist forces. Opposition to the military regimes, and indeed to capitalism, tended to be identified with opposition to the United States.

Finally, an important feature of the debates within the Korean political milieu is the question of the trades unions. In particular for the present generation of activists, the experience of trades unionism is based on the struggles in the 1980s and early 1990s, in which the unions were in large part clandestine, not yet "bureaucratised" and certainly both animated and led by profoundly dedicated militants (including comrades who today participate in the SPA and SGWC). Because of the conditions of clandestinity and repression, it was not clear to the militants involved at the time that the unions' "programme" was not only not revolutionary, but could not even defend workers' interests. During the 1980s, the unions were closely linked to the democratic opposition to the military regime, whose ambition was not to overthrow capitalism but quite the reverse: to overthrow the military regime and to take over the state capitalist apparatus itself. By contrast, the "democratisation" of Korean society since the 1990s has brought into the open this integration of the unions into the state apparatus, and caused a considerable disarray among militants as to how to react to this new situation: as one comrade put it "the unions turned out to be the best defenders of the democratic state". As a result, there is a general sense of "disappointment" with the unions and a search for some other method for militant activity within the working class. Again and again, in the interventions in the conference and in informal discussions, we could feel how urgent is the need for Korean comrades to have access to the reflection on the nature of the trades unions in capitalism's decadence which has formed such an important part of the reflection in the European workers' movement ever since the Russian revolution, and especially since the failure of the revolution in Germany.

The new millenium has thus witnessed the development of a real effort among many Korean militants to call into question the bases of their previous activity which had, as we have seen, been strongly influenced by the ideologies of both Stalinism and bourgeois democracy. In an effort to preserve some degree of unity and to provide a space for discussion among those involved in the process, a number of groups and individuals have taken the initiative of creating a more or less formal "Network of revolutionary marxists".[10] Inevitably, breaking with the past is extremely difficult and has led to a great deal of heterogeneity among the different groups in the Network. The historical conditions which we have described briefly above have meant that the differentiation between the principles of proletarian internationalism and the bourgeois, essentially nationalist, outlook that characterises Stalinism and Trotskyism has only begun during the last few years, on the basis of the practical experience of the 1990s, and largely thanks to the efforts of the SPA to introduce left communist ideas and positions within the Network.

In this context, there are two aspects of the SPA's introduction to the conference which are absolutely fundamental in our view:

- First, the explicit declaration that it is necessary for revolutionaries in Korea to place the experience of Korean workers within the wider historical and theoretical framework of the international working class: "The purpose of the international conference is to open widely the horizon of recognition by the theory and the practice with the perspectives of the world revolution. We hope that the revolutionary Marxists go hand in hand for solidarity and unity and accomplish the historical task to crystallise the world revolution with the world proletariat in this important conference".

- Second, that this can only be done on the basis of the principle of the Communist Left: "The international conference of revolutionary Marxists in Korea is the precious meeting and field of discussions between left communists of the world and the revolutionary marxists of Korea and the first manifestation of exposing the political positions [ie of left communists] within the revolutionary milieu."

The debates at the Conference

This article is too short to give an exhaustive account of the Conference's discussions. Rather, we will try to highlight what seem to us the most important points that emerged from them, in the hope of contributing to the continuation of the debates begun at the Conference both among the Korean comrades themselves and more generally within the internationalist movement world wide.

On the decadence of capitalism

This was the first subject under discussion, and before considering the debate itself, we should first say that we wholeheartedly support the underlying preoccupation of the SPA: to begin the Conference by giving a solid theoretical grounding to the other questions under discussion, namely the situation of the class struggle and revolutionary strategy. In addition, we salute the heroic effort of the SPA comrades to present a brief synthesis of the different views on the question that exist within the Communist Left. Given the complexity of the question - which has been a subject of debate within the workers' movement since the beginning of the 20th century, and has exercised some of its greatest minds - this was an extremely bold undertaking.

With hindsight, however, it may have been too daring! While it was very striking to see that the concept of the decadence of capitalism received an "instinctively" favorable reception (if we can put it like that), it was also clear from the questions posed both during the discussion and informally afterwards that most of the participants lacked the theoretical grounding to tackle the question in depth.[11] To say this is in no way a criticism: many of the basic texts are not available in Korean, which is itself an expression - as we said earlier - of the objective inexperience of the Korean workers' movement. We hope at least that the questions raised, and also the introductory texts presented by the SPA and the ICC in particular, will allow comrades to begin to situate themselves in the debate and also - just as importantly - to understand why this theoretical question is not something posed outside the real world and the concrete preoccupations of the struggle, but the fundamental determining factor of the situation in which we live today.[12]

It is worth taking up one question, from a young student, which expressed in a few words a striking contradiction between appearance and reality in present-day capitalism: "Many people feel decadence, we - the undergraduate students - are subject to bourgeois ideology, there is a feeling that there exists an affluent society, how can we express decadence in more concrete words?". It is true that an aspect of bourgeois ideology (at least in the industrialised countries) is the pretence that we are living in a world of "consumerist abundance" - and indeed the city streets of Seoul, the shops groaning with electronic goods, might seem to give a semblance of reality to the ideology. Yet at the same time, it is abundantly clear that Korean youth faces the same problems as young proletarians elsewhere: unemployment, precarious work contracts, a general difficulty in finding work, the high cost of housing. It is part of the task of communists to demonstrate clearly for today's working-class youth the link between the mass unemployment of which they are victims, and the generalised and permanent warfare which is the other fundamental aspect of capitalism's decadence, as we tried to point out in our brief reply to this question.

On the class struggle

Certainly one of the most important issues under discussion, not only at the Conference but within the Korean movement in general, was the question of the class struggle and its methods. As we understood it, again both from the interventions in the Conference and from informal discussion outside, the union question poses a real problem for the militants who took part in the struggles at the end of the 1980s. In some ways, the situation in Korea is analogous with that in Poland following the creation of the Solidarnosc union - and is yet another demonstration of the profound truth of the principles of the Communist Left: in capitalism's decadence, it is no longer possible to create permanent mass organisations of the working class. Even unions formed in the heat of struggle, as was the case in Korea, can only end up becoming an adjunct of the state, a means not for strengthening the workers' struggle but for strengthening the grip of the state over the workers' struggle. Why is this? Fundamentally, the reason is that it is impossible for the working class to win lasting reforms from capitalism in its decadent period. The unions have lost their original function, and remain tied to the preservation of capitalism. They have taken on a national viewpoint often, moreover, restricted to a single trade or industry, instead of an international viewpoint common to all workers: inevitably, they bow to the logic of capitalism, of "what the country can afford", of "what is good for the national economy". This indeed was one reproach we heard made of the unions in Korea - that they had even reached the point of urging workers to limit their demands to what the bosses are prepared to pay, rather than basing them on the needs of the workers themselves.[13]

Faced with this inevitable betrayal of the unions, and their integration into the democratic state apparatus, the Korean comrades were looking to the ideas of the Communist Left for a solution. Consequently, the notion of "workers' councils" has raised a great deal of interest there. The problem, is that there is a general tendency to see the workers' councils not as the organs of workers' power in a revolutionary situation, but in effect as a new kind of trade union able to exist permanently within capitalism. Indeed this idea was even theorised historically in a presentation on "The council movement strategy in the present period in South Korea, and how to put it into practice" by the "Militants group for revolutionary workers' party". We have to say that this presentation turned history completely on its head by claiming that the workers' councils created during the 1919 German revolution actually evolved out of the trades unions, which is the exact opposite of reality![14] In our opinion, this is not simply a matter of historical inaccuracy of the kind which could be settled by academic debate. It springs more profoundly from the fact that it is extremely difficult to accept the fact that outside a revolutionary period it is simply impossible for the workers to be permanently in struggle. Militants who are caught in this logic - independently of their sincere desire to work for the class struggle, and even independently of the proletarian political positions that they may genuinely defend - run the risk of falling into the trap of immediatism, constantly running after "practical" activity which bares no relationship to what is concretely possible within the real historical situation as it exists.

For the proletarian world outlook, posing the question in this way makes it impossible to answer. As one ICC delegate put it: "If the workers are not in struggle, then it is impossible to hold a gun to their heads, and tell them 'You must struggle!'". Nor is it possible for the revolutionaries to struggle "on behalf of" the working class. Revolutionaries cannot provoke the class struggle: this is not a principle, it is simply a historical fact. What they can do, is contribute to the development of the working class' own awareness of itself, of its place in society as a class with its own interests and above all with revolutionary goals which go beyond the immediate struggle, beyond the workers' immediate situation in the factory, the office, or the dole queue. This is one of the keys to understanding apparently "spontaneous" proletarian uprisings such as that of 1905 in Russia: despite the fact the the revolutionaries of the day played little part in the initial upsurge of struggle, the terrain had been prepared for years by the systematic intervention of the Social-Democracy (the revolutionaries of the day), which had played a critical role in developing the workers' awareness of themselves as a class.[15] To put it briefly, outside periods of open workers' struggle, the essential task of revolutionaries is one of propaganda and the development of those ideas which will strengthen the struggle to come.

There is another question raised in the presentations by Loren Goldner and the Internationalist Perspective delegate, which we feel should not go unanswered: the idea that the "recomposition" of the working class - in other words on the one hand the tendency towards the disappearance of the mega-factories characteristic of the late 19th and 20th centuries in favour of geographically widespread production processes, and on the other the increasingly precarious work conditions of the workers, especially young workers (short-term contracts, unemployment, part-time working, etc.) - has led to the discovery of "new methods of struggle" which go "beyond the workplace". The most notable examples of these "new methods of struggle" are the "flying pickets" supposedly invented by the piqueteros movement in Argentina 2001 and the riots in the French suburbs during 2005. We do not propose, in this article, to answer the comrades' enthusiasm for the French riots and the piqueteros movement, which in our view is profoundly misplaced.[16] However, we do think it necessary to take up a more general political error which is expressed in these positions, which is that the workers' revolutionary consciousness in effect depends on their immediate day to day experience in the workplace.

In fact, not only are precarious working conditions and "flying pickets" not new historically,[17] the supposed "new forms of struggle" that are generally held up for our admiration are nothing other than expressions of the workers' powerlessness in a given situation: the riots of the youngsters in the French suburbs in 2005 are a classic example. The reality is that (in the period of capitalism's decadence) whenever the workers' struggle acquires a certain independence it has tended to organise itself not in unions but in mass meetings with elected delegates; in other words, in an organisational form that both is descended from and prefigures the soviets. The most striking example of recent history is of course the struggles in Poland in 1980; another experience, again in the 1980s, was that of the Cobas (rank-and-file committees) formed during the massive teachers' struggles in Italy (hardly a "traditional" industrial sector!). Nearer to us in time we can point to the strikes in Vigo (Spain) in 2006.[18] Here, the engineering workers who began the strike mostly work on precarious contracts in small-scale industry. Since there was no single large factory which could form the focal point for the struggle they held daily mass meetings, not in the workplace but in the town square. These mass meetings in turn looked back to a form of organisation that had already been used in 1972 in the same town.

The question then is this: why is it that at the end of the 19th century the development of mass precarious workforces led to the formation of the first mass unions of unskilled workers, whereas in the 21st century this is no longer the case?

Why did the Russian workers in 1905 invent the workers' council - the soviet - which Lenin called "the finally discovered form of the dictatorship of the proletariat"?

Why has the mass meeting become the typical form of workers' organisation for struggle whenever the workers' succeed in developing their autonomy and strengh?

In our opinion, as we said at the time, the answer lies not in sociological comparisons but in a far broader political understanding of the change in historical period that took place at the beginning of the 20th century, which was described by the Third International as opening up an "epoch of wars and revolutions".

Moreover, the sociological vision of the working class defended by IP and Loren Goldner strikes us as a complete underestimation of the proletariat's political, theoretical capacities. It is almost as if workers were only capable of thinking about what is happening in the workplace, as if their brains switched off as soon as they leave work, as if they do not concern themselves with their children's future (problems of schools, education, social decomposition), about solidarity with the old and sick, and with the generations to come (problems of declining health service facilities, of pensions), as if they were incapable of viewing the problems of the environment or the endless barbarity of war with a critical eye, and tying what they learn about the wider world to their own direct experience of capitalist exploitation in the workplace.

Nor is this broad, political and historical understanding of the world necessary only for the immediate struggle. If the world proletariat is to be successful in overthrowing capitalism, it will have to build a completely new society in its place, a society of a kind that has never existed in humanity's history. To do so, it must be capable of developing the most profound comprehension of human history, it must be able to claim as its heritage humanity's greatest achievements in art, in science, and in philosophy. This is precisely what the political organisations of the working class are for: they are a means by which the workers think more generally about their condition and the perspectives that are open to them.[19]

The Declaration against the threat of war

We have already published the text of the Declaration on our website and in our press, and will not repeat its content here.[20] The debate around its content concentrated on the proposal put forward by a member of the Ulsan Labour Education Committee to lay the major responsibility for the increasing tension in the region at America's door, and in effect to present North Korea as a "victim" of the US policy of containment. This proposal, and the support it received from some of the more Trotskyist tendencies in the Conference was, we think, significant of the difficulty that many Korean comrades have in breaking with the "anti-imperialist" (for which read essentially "anti-American") ideology of the 1980s, and an continuing attachment to the defence of North Korea and so to Korean nationalism, despite their undoubtedly sincere rejection of Stalinism.

Both the ICC and several SPA comrades argued strongly against changing the main thrust of the Declaration. As we pointed out in the debate on the Declaration both in Seoul and in Ulsan, the idea that one country in an imperialist conflict is "more to blame" than another, is exactly the same idea that allowed the Social-Democratic traitors to call workers to support "their" nation in 1914: the German workers against "Tsarist barbarism", the French workers against "Prussian militarism", the British workers in support of "plucky little Belgium", and so on. For us, the period of capitalism's decadence has demonstrated the profound truth of Rosa Luxemburg's understanding that imperialism is not the fault of this or that country, but a fundamental feature of capitalism itself: in this epoch, all states are imperialist. The only difference between the US giant and the North Korean pigmy is the size of their imperialist appetites, and their ability to satisfy them.

Two other objections arose during the discussion, which we feel are worth mentioning. The first, was the proposal by a comrade from the "Solidarity for workers' liberation" group to include a point denouncing the South Korean government's taking the tense situation as an excuse to step up repressive measures. This very justified suggestion was made during the discussion in Seoul, and the final version debated in Ulsan the next day (and since published) was modified accordingly.

The second objection, from a comrade from the "Sahoejueo Nodongja" group,[21] was that the actual situation was not in fact that serious, and that denouncing war now would in effect give credence to a war scare being orchestrated by the bourgeoisie for its own purposes. This objection is a reasonable one, but nonetheless mistaken in our view. Whether or not there is an imminent threat of war in the Far East, there can be no doubt that the threat of war hangs over this region and that the tensions between the different major players on the imperialist scene (China, Taiwan, Japan, USA, Russia) are increasing. In this situation, we consider it of great importance that internationalists should be able to denounce the responsibility of all the imperialist camps: in doing so, we are following in the steps of Lenin, Luxemburg, and the Left of the Second International who fought for the internationalist resolution voted by the 1907 Stuttgart Congress. It is a primary responsibility of revolutionary organisations to take position within the proletariat on the crucial events of imperialist conflict or the class struggle.[22]

To conclude on this point, we would like to salute the fraternal internationalist support for the Declaration given by the IP delegate and other comrades present as individuals at the Conference.

A balance-sheet

At a final meeting before our delegation's departure, the ICC and SPA found ourselves in complete agreement in our overall assessment of the Conference. The most significant points raised were the following:

- The fact that this Conference could take place is itself an event of historic importance, since it represents the first time that the positions of the Communist Left have been defended and begun to take root in a highly industrialised country of the Far East.

- The SPA considered that the discussions during the Conference had been of particular importance in demonstrating in practice the fundamental difference between the Communist Left and Trotskyism. In doing so, the Conference reinforced the SPA's determination to develop its own understanding of Left Communist principles, and to make these more widely available in the Korean workers' movement.

- The joint Declaration about the North Korean nuclear tests were a concrete expression of the internationalist positions of the Communist Left, in particular of the SPA and ICC. The debate over the Declaration revealed the problem of nationalistic tendencies remaining in the Korean workers movement. Within the "network" there are divergences on this, this problem is unsolved in the milieu, and the SPA is resolved to work to overcome this in the future.

- One of the most important questions for future debate is that of the trades unions. It will be necessary for the comrades in Korea to analyse the history of the unions there, especially since the 1980s, in the light of the historical experience of the world proletariat, as this is concentrated in the positions defended by the communist left.

Perspectives

For all its importance, we are well aware that this Conference is only one step in developing the presence of left communist principles in the Far East, and common work between revolutionaries in East and West. That said, we consider that the fact the Conference was held, and the debates within it, have confirmed two points on which the ICC has always insisted, and which will be fundamental for the construction of the future world communist party of the working class.

The first of these is the political foundation on which such an organisation will be built. On all the fundamental questions - the union question, the parliamentary question, the question of nationalism and national liberation struggles - the development of a new internationalist movement can only be accomplished on the basis of the groundwork laid by the small groups of the Communist Left between the 1920s and 50s (notably by Bilan, the KAPD, the GIK, the GCF), where the ICC draws its origins.[23]

Secondly, the conference in Korea, and the SPA's explicit call to "accomplish the solidarity of the world proletariat", is yet another confirmation that the internationalist movement is not developing on the basis of a federation of existing national parties, but directly on an international level.[24] This is a historical advance over the situation when the Third International was created, in the midst of the revolution and on the basis of the left fractions that had emerged from the national parties of the Second International. It also reflects the nature of the working class today: a class which, more than ever in history, is united in a world wide process of production, and in a global capitalist society whose contradictions can only be overcome by its overthrow on a world scale, to be replaced by a world wide human community.

[1] We should also mention the invention, in the 15th century, of the han-gǔl alphabet, perhaps the first attempt to create a notation based on a scientific study of the language in its spoken form.

[2] This included the forced prostitution of thousands of Korean women in the Japanese army's military brothels, and the demolition of the old agrarian economy as Korean farming was more and more directed by the food requirements of Japan itself.

[3] "The United States is interested in the creation of a military barrier between non-Communist and Communist areas. If that barrier is to be effective, the areas behind it must be stable (...) The United States must determine the particular causes of unrest and intelligently and boldly assist in their removal. Our experience in China has shown that it is useless to temporize with the causes of unrest; that a policy looking towards temporary stability is doomed to failure when the general desire appears to be for permanent change", Melvin Conant Jnr, "JCRR: an object lesson", in Far Eastern Survey, May 2nd, 1951.

[4] "The Asian dragons run out of steam", in International Review n°89 (1997)

[5] The first and most important source of finance was the acquisition by the chaebols of assigned goods at prices well under their value. Just after the war this made up 30% of what South Korea inherited from the Japanese. Initially placed under the control of the American office of assigned goods, they were distributed by the office itself and by the Korean government.

[6] We do not propose, in this article, to deal with the situation of the working class in North Korea, which has had to suffer all the horrors of an ultra-militarist Stalinist regime.

[7] Andrew Nahm, A history of the Korean people.

[8] The Philippines, and Brazil are examples that spring immediately to mind.

[9] Some comrades of the SGWC took part in the conference in an individual capacity.

[10] Apart from the SPA, the following Korean groups belonging to the Network gave presentations to the conference: Solidarity for Workers' Liberation, Ulsan Labour Education Committee, Militants' Group for Revolutionary Workers' Party. A presentation on the class struggle was also given by Loren Goldner, in an individual capacity.

[11] This was particularly true of the discussion on decadence, held in Seoul, which was open to the public and therefore included in the audience a number of young students with little or no political experience.

[12] We do not propose to examine here the Internationalist Perspective group's obsession with the "formal and real domination of capital". We have already dealt with the subject at some length in International Review n°60 , published in 1990 at a time when IP still called itself the "External Fraction of the ICC". It is nonetheless worth mentioning that IP's first effort at demonstrating in practice the superiority of its "new" theoretical insight was hardly convincing, since IP continued to insist two years after the collapse of the Berlin Wall that events in Eastern Europe actually represented a strengthening of Russia!

[13] Inevitably, this account remains extremely schematic and open to correction and precision. We can only regret that the presentation by the comrade from ULEC on the history of the Korean workers' movement was far too long to be translated into English and therefore remains inaccessible to us. We hope that it will be possible for the comrades to prepare and translate a shorter version of their text which would summarise its main points.

[14] In fact, the unions during the German revolution were the worst enemies of the soviets. For an account of the German revolution, see the articles published in International Review n°80-82

[15] See our series on the 1905 revolution published in International Review n°120, 122, 123, 125.

[16] For more detail on these subjects, see for example "Riots in the French suburbs: in the face of despair, only the class struggle offers a future ", and "Argentina: the mystification of the 'piquetero' movement ", published in International Review n°119. We have to say also that putting forward the idea of the "disappearance" of a mass industrial workforce came across as somewhat surreal in the town of Ulsan, where the Hyundai factory alone employs 20,000 workers!

[17] If we take as an example the idea that "precarious working" led to the invention of the "flying picket" as a "new form of struggle", we can see that this idea is simply unfounded historically. The flying picket (ie delegations of workers in struggle going to other workplaces to bring other workers into the movement) has been around for a long time: to take the example of Britain alone, the flying picket was famously used in two important struggles during the 1970s: the miners' strikes of 1972 and 1974 when the miners sent pickets to the power stations, and the 1972 building workers' strike, when the builders sent pickets to spread the strike to different building sites. Nor is the existence of a "precarious" workforce anything new. Indeed it was precisely the emergence of a mass unskilled precarious workforce (particularly in the docks) that led to the formation of the revolutionary syndicalist Tom Mann's "General Labourers' Union" in 1889 (Engels and Marx's daughter Eleanor were also involved in the development of this union).

[18] See the article published in World Revolution n°295

[19] The communists "do not set up any sectarian principles of their own, by which to shape and mould the proletarian movement. The Communists are distinguished from the other working-class parties by this only: 1. In the national struggles of the proletarians of the different countries, they point out and bring to the front the common interests of the entire proletariat, independently of all nationality. 2. In the various stages of development which the struggle of the working class against the bourgeoisie has to pass through, they always and everywhere represent the interests of the movement as a whole. The Communists, therefore, are on the one hand, practically, the most advanced and resolute section of the working-class parties of every country, that section which pushes forward all others; on the other hand, theoretically, they have over the great mass of the proletariat the advantage of clearly understanding the lines of march, the conditions, and the ultimate general results of the proletarian movement." (Communist manifesto).

[20] The declaration can be found online .

[21] In English, "Socialist Worker": despite the name, this group has nothing to do with the British "Socialist Workers' Party". We apologise in advance if we have misrepresented the comrade's line of thought - the language barrier may have led us to an error of interpretation.

[22] The fact that the internationalists in this conference did not remain voiceless in the face of the threat of war is in our view a real step forward compared to the conferences of the Communist Left at the end of the 1970s, where the other participants - and notably Battaglia Comunista and the CWO - refused any joint statement on the invasion of Afghanistan by the USSR.

[23] According to IP, we have to go "beyond the Communist Left". Nobody, least of all those groups we have cited, would pretend that they had said the final word on these or any other questions: history moves forward, and we come to understand past history better. But it is impossible to build a house without laying the foundations, and in our view the only foundations on which it is possible to build are those of our predecessors of the Communist Left. The logic of IP's position is to throw out the history from which we spring - and to declare that "history starts with us". However much IP may dislike the idea, this is nothing but a variant of the Bordigist position that "the party" (or in the IBRP's case, "the Bureau") is the unique font of wisdom and has nothing to learn from anybody else.

[24] This aspect of the development of the future international organisation was a matter of polemic between in the ICC and the IBRP in the 1980s, the IBRP holding that an international organisation could only be built on the basis of independent political organisation pre-existing in different countries. The real practice of the internationalist movement today completely invalidates this theory of the IBRP.

Life of the ICC:

Geographical:

The theory of decadence is the key to understanding the conditions and principles of the proletarian struggle

- 3151 reads

The concretisation of historical materialism

The theory of decadence is nothing other than the concretisation of historical materialism in the analysis of the evolution of modes of production. It is thus the indispensable framework for understanding the historical period we are living in. Knowing whether society is still progressing, or whether it has had its day historically, is decisive for grasping what is at stake on the political and socio-economic levels, and acting accordingly. As with all past societies, the ascendant phase of capitalism expressed the historically necessary character of the relations of production it embodies, that is, their vital role in the expansion of society's productive forces. The phase of decadence, by contrast, expresses the transformation of these relations into a growing barrier to this same development. This is one of the main theoretical acquisitions left us by Marx and Engels.

The 20th century was the most murderous in the entire history of humanity, both in the scale, the frequency and length of the wars which took up a large part of it, and in the incomparable breadth of the human catastrophes which it produced: from the greatest famines in history to systematic genocide, taking in economic crises which have shaken the whole planet and hurled tens of millions of proletarians and human beings into abject poverty. There is no comparison between the 19th and 20th centuries. During the Belle Epoque, the bourgeois mode of production reached unprecedented heights: it had united the globe, reaching levels of productivity and technological sophistication which could only have been dreamed about before. Despite the accumulation of tensions in society's foundations, the last 20 years of capitalism's ascendancy (1894-1914) were the most prosperous yet; capitalism seemed invincible and armed conflicts were confined to the peripheries. Unlike the "long 19th century" (as the historian EJ Hobsbawm has described it), which was a period of almost uninterrupted moral, intellectual and material progress, since 1914 there has been a marked regression on all fronts. The increasingly apocalyptic character of economic and social life across the planet, and the threat of self-destruction in an endless series of conflicts and ever more grave ecological catastrophes, are neither a natural fatality, nor the product of simple human madness, nor a characteristic of capitalism since its origins: they are a manifestation of the decadence of the capitalist mode of production which, from being, from the 16th century to the First World War,[1] a powerful factor in economic, social and political development, has become a fetter on all such development and a threat to the very survival of humanity.

Why is humanity faced with the question of survival at the very moment that it has achieved a level of development in the productive forces that would enable it to start moving, for the first time in its history, towards a world without material poverty, towards a unified society capable of basing its activity on the needs, desires and consciousness of mankind? Does the world proletariat really constitute the revolutionary force that can take humanity out of the impasse into which capitalism has led it? Why is it that most of the forms of workers' struggle in our epoch can no longer be those of the last century, such as the fight for gradual reforms through trade unionism, parliamentarism, supporting the constitution of certain nation states or certain progressive fractions of the bourgeoisie? It is impossible to find one's bearings in the current historical situation, still less to play a vanguard role, without having a global, coherent vision which can answer these elementary but crucial questions. Marxism - historical materialism - is the only conception of the world which makes it possible to give such an answer. Its clear and simple response can be summed up in a few words; just like the modes of production which came before it, capitalism is not an eternal system: "Beyond a certain point, the development of the productive forces becomes a barrier to capital, and consequently the relation of capital becomes a barrier to the development of the productive forces of labour. Once this point has been reached, capital, ie wage labour, enters into the same relation to the development of social wealth and the productive forces as the guild system, serfdom and slavery did, and is, as a fetter, necessarily cast off. The last form of servility assumed by human activity, that of wage labour on the one hand and capital on the other, is thereby shed, and this shedding is itself the result of the mode of production corresponding to capital. It is precisely the production process of capital that gives rise to the material and spiritual conditions for the negation of wage labour and capital, which are themselves the negation of earlier forms of unfree social production.

The growing discordance between the productive development of society and the relations of production hitherto characteristic of it, is expressed in acute contradictions, crises, convulsions" ("Outlines of the Critique of Political Economy" [also known as the Grundrisse], Collected Works Vol. 29, 133-4).

As long as capitalism fulfilled a historically progressive role and the proletariat was not sufficiently developed, proletarian struggles could not result in a triumphant world revolution; they did however allow the proletariat to recognise itself and assert itself as a class through the trade union and parliamentary struggle for real reforms and lasting improvements in its living conditions. From the moment when the capitalist system entered into decadence, the world communist revolution became a possibility and a necessity. The forms of the proletarian struggle were radically overturned; even on the immediate level, defensive struggles could no longer be expressed, either in form or content, through the means of struggle forged last century such as trade unionism and parliamentary representation for workers' political organisations.

Brought into being by the revolutionary movements which put an end to the First World War, the Communist International was founded in 1919 around the recognition that the bourgeoisie was no longer a historically progressive class: "2. THE PERIOD OF CAPITALIST DECLINE. On the basis of its assessment of the world economic situation the Third Congress was able to declare with complete certainty that capitalism had fulfilled its mission of developing the productive forces and had reached a stage of irreconcilable contradiction with the requirements not only of modern historical development, but also of the most elementary conditions of human existence. This fundamental contradiction was reflected in the recent imperialist war, and further sharpened by the great damage the war inflicted on the conditions of production and distribution. Obsolete capitalism has reached the stage where the destruction that results from its unbridled power is crippling and ruining the economic achievements that have been built up by the proletariat, despite the fetters of capitalist slavery... What capitalism is passing through today is nothing other than its death throes" (‘Theses on Comintern Tactics' in Theses, resolutions and manifestos of the first four Congresses of the Third International, Hessel, p388-9)

From then on, the understanding that the First World War marked the entry of the capitalist system into its decadent phase has been the common patrimony of the majority of the groups of the communist left who, thanks to this historical compass, have been able to remain on an intransigent and coherent class terrain. The ICC has only taken up and developed the heritage transmitted and enriched by the Italian, German and Dutch lefts in the 1930s and 40s and then by the Gauche Communiste de France in the 1940s and 50s.

Decisive class combats are on the horizon. It is therefore more than ever vital for the proletariat to re-appropriate its own conception of the world, which has been developed over nearly two centuries of workers' struggles and theoretical elaboration by its political organisations. More than ever, the proletariat must understand that the present acceleration of barbarism and the uninterrupted increase in its exploitation are not a fact of nature, but are the result of the economic and social laws of capital which continue to rule the world even though they have been historically obsolete since the beginning of the 20th century. It is more vital than ever for the working class to understand that while the forms of struggle it learned in the 19th century (minimum programme of struggle for reforms, support for progressive fractions of the bourgeoisie etc) had a sense in the period of capitalism's ascent when it could "tolerate" the existence of an organised proletariat within society, these same forms can only lead it into an impasse in the period of decadence. More than ever, it is vital for the proletariat to understand that the communist revolution is not an idle dream, a utopia, but a necessity and a possibility which have their scientific foundations in an understanding of the decadence of the capitalist mode of production.

The decadence of capitalism

As a result of historical evolution, labour power becomes a commodity

Under capitalism, labour power has become a commodity:

"In ancient times, we see the exploitation of surplus labour by those who do not work. Slavery in antiquity, serfdom in the Middle Ages, both depend on a certain level of productivity being reached, on the ability of one individual's labour to support several individuals. Each is a different expression of the way in which one social class profits from this productivity by living on the labour of another class. In this sense, the slave of Antiquity and the medieval serf are the direct ancestors of today's wage worker. But neither in Antiquity nor in the Middle Ages had labour power become a commodity, despite its productivity and the fact that it is exploited (...)

The sale of labour power as a commodity implies a whole series of specific historical and social relations. The appearance on the market of the commodity 'labour power' means:

- that the worker is free as an individual;

- that he is separated from the means of production, and that the latter are brought together under the ownership of those who do not work;

- that labour productivity has reached a high level, in other words that it can provide surplus labour;

- that the market economy has become dominant, in other words that the creation of surplus labour in the form of commodities is the aim of the purchase of labour power" (Rosa Luxemburg, Introduction to political economy,[2] Chapter V, "Wage Labour").

For the proletariat, the result was to introduce a new quality to its destitution, compared to previous epochs:

"The primitive tribe is hungry, occasionally or often, when natural conditions are unfavourable to it; its destitution is that of society as a whole, it was unthinkable that some its members could be destitute while others were rich; inasmuch as the means of life were available for the whole of society, they were equally to all of its members. The same is true of antique and oriental slavery. However pressured and exploited the Egyptian public slave or the Greek private slave, however great a gap between his meagre living conditions and the opulence of his master, his conditions as a slave nonetheless ensured his existence. Slaves were not left to die of hunger, just as nobody left their horse or their cattle to die of hunger. The same is true of medieval serfdom: the whole system of feudal dependence where the peasant was attached to the land and where everyone was either the master or the servant of other men, or both at once, attributed to each individual a determined place within society. However pressured were the serfs, no lord had the right to chase them from the land and therefore to deprive them of their means of existence. Feudal relations obliged the lord to help the peasants in the case of catastrophes, fires, floods, hail, etc. It is only at the end of the Middle Ages, when feudalism begins to collapse and modern capitalism makes its appearance, that the situation changes.

(...)

capitalist commodity production is the first form of economy in human history where the absence of work and of the means of existence for a large and growing part of the population, and the poverty of another, also growing, part are not only the consequence but also a necessity and the condition for the existence of the economy." (Rosa Luxemburg, op.cit.).

Capitalism creates the conditions for communism

The Communist Manifesto emphasises the eminently revolutionary role played by the bourgeoisie, as it swept away all the old limited forms of society, and replaced them by the most dynamic and expansionist mode of production ever seen; a mode of production which, by conquering and unifying the entire planet, and by setting in motion in enormous productive forces, laid the foundations for a higher form of society which will at last be able to do away with class antagonisms.

Communism has thus becomes a material possibility thanks to the unprecedented development of the productive forces by capitalism itself.

The society based on the universal production of commodities is inevitably condemned, by the logic of its own internal functioning, to decline and in the end to collapse. In the Manifesto, the internal contradictions which will lead to capitalism's fall were already identified:

"Modern bourgeois society with its relations of production, of exchange and of property, a society that has conjured up such gigantic means of production and of exchange, is like the sorcerer, who is no longer able to control the powers of the nether world whom he has called up by his spells. For many a decade past, the history of industry and commerce is but the history of the rovolt of modern productive forces against modern conditions of production, against the property relations that are the conditions for the existence of the bourgeoisie and its rule. It is enough to mention the commercial crises that by their periodical return put on trial, each time more threateningly, the existence of the entire bourgeois society. In these crises a great part not only of the existing products, but also of the previously created productive forces, are periodically destroyed. In these crises there breaks out an epidemic that, in all earlier epochs, would have seemed an absurdity - the epidemic of overproduction. Society suddenly finds itself put back into a state of momentary barbarism; it appears as if a famine, a universal war of devastation had cut off the supply of every means of subsistence; industry and commerce seem to be destroyed; and why? Because there is too much civilisation, too much means of subsistence, too much industry, too much commerce." (Manifesto of the Communist Party in Marx: the revolutions of 1848, Pelican Marx Library, p72-73)

Marx's work in the years after he wrote the Manifesto was to look more closely at the relationship between the extraction and the realisation of surplus value, and at the periodic crises of overproduction which, every ten years or so, shook capitalist society to its foundations. In unveiling the secret of surplus value, he showed that capitalism is marked by profound contradictions which will inevitably lead to its decline and final collapse. These contradictions are based on the very nature of wage labour:

- the crisis of overproduction: under capitalism, the majority of the population is, by the very nature of surplus value, made up of over-producers and under-consumers. Capitalism is unable to realise all the value that is produced within the closed circuit of its own relations of production;

- the tendency of the rate of profit to fall: only human labour power can create new value; however, competition constantly obliges capitalism to reduce the quantity of living labour in relation to dead labour (machines, raw materials), which exerts a downward pressure on the rate of profit.

Despite its incredibly expansionist nature and the dynamic by which it subjects the whole planet to its laws, capitalism is - like Roman slave society or medieval feudalism - a historically transitory mode of production. At the end of this vast historical movement, like all modes of production that preceded it, capitalism is therefore condemned to disappear not because of its moral bankruptcy but because its internal contradictions compel it to destroy itself, and because it has produced within itself a class able to replace it by a higher form of social organisation.

Capitalism's contradictions also pointed to their solution: communism. A society plunged into chaos by the domination of commodity relationships can only be superseded by a society which abolishes wage labour and production for exchange, the society of "producers freely associated" for the satisfaction of human needs, where the relationships between human beings will be no longer obscure, but simple and clear.

During the last years of his life, Marx devoted a large part of his intellectual energy to the study of archaic societies. The publication of Morgan's Ancient society and the questions posed to him by the Russian workers' movement on the perspectives for the revolution in Russia, led him to undertake an intensive study which has come down to us in the form of his very incomplete but nonetheless extremely important Ethnographic notes. The same study also underpinned Engels' great anthropological work, The origins of the family, private property and the state.

For Marx and Engels, Morgan's work on the American Indians was a striking confirmation of their ideas about primitive communism: contrary to the conventional bourgeois conception that private property, social hierarchy, and the inequality of the sexes were inherent to human nature, Morgan's study revealed that the more primitive was a social formation, the more property was held in common, the more also the process of decision-making was collective and the more relationships between men and women were based on mutual respect.

Marxist approach to primitive society was founded on his materialist method which considered that the historical evolution of societies is determined, in the last instance, by changes in their economic infrastructure. These changes brought about the end of the primitive community and opened the way to the appearance of more developed social forms. But his vision of historical progress was radically opposed to the trivial bourgeois evolutionism which imagined a purely linear ascension from darkness into light, an ascension whose culmination is of course the brilliant splendour of bourgeois civilisation. Marx's viewpoint was profoundly dialectical: far from rejecting primitive communism as subhuman, his Notes express a profound respect for the qualities of the tribal community: its ability to govern itself, its powers of imagination and artistic creation, its sexual equality. The inevitable limitations of primitive society - in particular, restrictions imposed on individuals and the division of humanity in the tribal units - were necessarily overcomes by historical progress. But the positive side of these societies was lost during this process and would have to be restored at a higher level in the communist future.

The discovery that human beings had lived for hundreds of thousands of years in a society without classes and without a state was to become a powerful instrument in the hands of the workers' movement and served to counterbalance all those proclamations according to which the love of private property and the need for hierarchy are an intrinsic part of human nature.

The imperialist phase, capitalism's apogee and prelude to its decadence

When the Communist Manifesto was written, the cyclical crises of overproduction could still be overcome "by the conquest of new markets, and by the more thorough exploitation of the old ones": capitalism still had before it a long phase of expansion.

During the 1870s and 1880s a new phase in capitalism's life opened up. The capitalist system entered its last phase of expansion and world conquest, no longer through the class struggle of emerging bourgeoisie seeking to establish viable national states, but through the method of imperialism and colonial conquest. During the last three decades of the 19th century almost the entire planet was conquered and shared out between the great imperialist powers.

With the appearance of the first signs of capitalism's decadent phase - growing tensions between the great powers and incessant conflicts on the periphery - as Engels was to write in 1891 with remarkable prescience: "All the above was said with the reservation that Germany will be able to pursue its economic and political development in peace. A war would change all that. And war is liable to break out at any moment. Everyone knows what war means today. It would be Russia and France on one side; Germany, Austria and perhaps Italy on the other" ('Socialism in Germany' 1891, in Marx and Engels Collected Works vol 27 p241) "But if war is to break out nevertheless, one thing is certain. This war, in which fifteen to twenty million armed men would slaughter one another and devastate Europe as it has never been devastated before - this war would either lead to the immediate triumph of socialism, or it would lead to such an upheaval in the old order of things, it would leave behind it everywhere such a heap of ruins, that the old capitalist society would become more impossible than ever..." (p245).

Before the outbreak of social disaster of World War I, many influential voices within the workers movement tried to convince the working class that capitalism could be transformed peacefully through reforms.

Fortunately at the time, the Marxist left was able to see through the apparently robust health of capitalism as expressed in its economic statistics. In reality, when the war broke out, capitalism was at the height of its economic prosperity and it was by walking in Engels' footsteps that the Marxist left was able to undertake an implacable struggle against the reformists within the social democracy, and to take account of the exacerbating contradictions of the system.

The understanding of the phase of imperialism and of capitalist decadence was to be developed by Marx's successors, and notably by Rosa Luxemburg.

The 20th century: the century of wars and revolutions

Although the Marxist left was far from being united on the fundamental reasons that had led capitalism to World War I - and a qualitatively and quantitatively new phenomenon in social life - it was nonetheless able to agree on its immediate cause: this was a war between great imperialist powers to divide up the world between them. Obviously those who were the most interested in a new division of the world, and were ready to go to war for it, were the least well endowed in colonies: Germany in particular. The others (Britain, France) were equally ready for war to avoid losing their colonial empires.

As an international wave of indignation against the barbarism of World War I was transformed into a world revolutionary wave which could put on the historical agenda the overthrow of the bourgeoisie and the creation of a communist society, there were those within the workers' movement who took refuge in "Marxist orthodoxy" to decree that the seizure of power by the working class in Russia was premature because it had not yet been preceded by the political seizure of power by the bourgeoisie. This polarisation on the supposed immaturity of revolutionary conditions in Russia was not only completely mistaken as to the development of industry and the working class in that country, but above all completely missed the fundamental point that conditions were ripe for a worldwide revolution.

Carried by the wave of revolutionary movements which had put an end to World War I, the foundation of the Communist International in 1919 was based, as we have seen above, on the understanding that the historically progressive role of the bourgeoisie had come to an end.

The fact that the revolution was defeated in no way indicates that the objective conditions for revolution were not yet ready in this period. Not only were the preconditions for a society of abundance already present thanks to the development of productive forces but the working class had already demonstrated, in 1905 in Russia and in several industrialised countries from 1917 onwards, its ability to overthrow the bourgeoisie and set up its own political power world wide.

This defeat, due fundamentally to the defeat of the revolution in Germany, in fact expresses the immaturity of the subjective conditions for the revolution, in particular the continued illusions of a large part of the German proletariat in the Social Democracy despite the latter's betrayal during the war.

The economic foundations of capitalist decadence

The world war, the first brutal manifestation of capitalism's entry into its decadent phase, was obviously not unconnected with the contradictions which had developed within society's economic foundations. Indeed it is a pure product of these contradictions.

A) the underlying economic causes of wars in the decadent period

As we have already pointed out, Marx had demonstrated both the absolute necessity for capitalism to realise a part of its surplus value in exchange with the non-capitalist world, and the fact that this necessity is a result of the mode of appropriation of surplus value which is specific to capitalism: wage labour. It is this that forces the capitalist to reduce the workers' wages to the minimum possible, such that the latter are unable to buy commodities which are not strictly necessary for the reproduction of their labour power, and therefore to constitute a factor in enlarging the solvent market within capitalism. Whence the necessity for capitalism constantly to search for outlets outside the sphere of its own relations of production: